Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

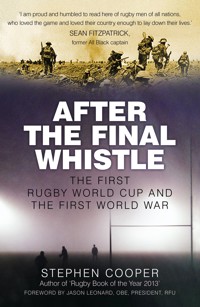

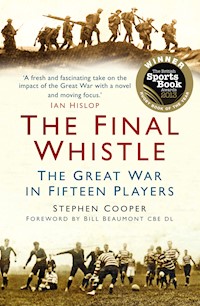

WINNER OF THE BRITISH SPORT BOOK AWARDS - RUGBY BOOK OF THE YEAR This is the story of 15 men killed in the Great War. All played rugby for one London club; none lived to hear the final whistle. Rugby brought them together; rugby led the rush to war. They came from Britain and the Empire to fight in every theatre and service, among them a poet, playwright and perfumer. Some were decorated and died heroically; others fought and fell quietly. Together their stories paint a portrait in miniature of the entire War. The Final Whistle plays tribute to the pivotal role rugby played in the Great War by following the poignant stories of fifteen men who played for Rosslyn Park, London. They came from diverse backgrounds, with players from Australia, Ceylon, Wales and South Africa, but they were united by their love of the game and their courage in the face of war. From the mystery of a missing memorial, Cooper's meticulous research has uncovered the story of these men and captured their lives, from their vanished Edwardian youth and vigour, to the war they fought and how they died.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 658

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my grandfather, William, who fought and lived through it,to my parents who grew up during the nextand to Sam and Ben, that they should never

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword by Bill Beaumont CBE DL

Acknowledgements

The First Blow

The Final Whistle

The Boys Who Won the War

1 Charles George Gordon Bayly: The First of the Gang

2 Guy du Maurier: The Accidental Playwright

3 Alec Todd: Lions led by a Lion

4 Eric Fairbairn: Body between your Knees

5 Nowell Oxland: A Green Hill Far Away

6 Jimmy Dingle: ‘A Gentleman, who made us Tea’

7 Syd Burdekin: From the Uttermost Ends of the Earth

8 Guy Pinfield: An Irish Tragedy

9 John Bodenham: ‘Your Affectionate son Jack’

10 Wilfred Jesson: ‘Bowled out, middle peg’

11 John Augustus Harman: The Man Who Hunted Zeppelins

12 Denis Monaghan & J.J. Conilh de Beyssac: Tin Can Allies

13 Robert Dale: ‘They go Down, Tiddly, Down, Down’

14 Arthur Harrison: Close the Wall up with our English Dead

15 Charles Button: The Thin Red Stripe

The Game that Won the War

Rosslyn Park Great War Roll of Honour

Notes

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

Stephen Cooper has played and coached rugby for over forty years. After Cambridge, he worked in advertising and now runs a military charity. His grandfather survived the Battle of the Somme and inspired in him a lifelong fascination with the First World War. He lives in London.

‘A fresh and fascinating take on the impact of the Great War with a novel and moving focus.’

Ian Hislop

‘This is a deeply moving book about the loss of fifteen members of Rosslyn Park rugby club during the Great War. A war that scarred Britain and took so many fine men, who had they lived would have enriched this country. The lives of these young men, all so promising, are poignantly and vividly recalled by historian Stephen Cooper.’

Max Arthur

‘Stephen Cooper has written a haunting and beautiful book. Here we see the grinding slaughter and the everyday humanity of men hurled into the abyss of modern warfare at its most terrible. His book tells the story of men from one rugby club but it is a universal narrative of heroism and loss. He writes superbly and has produced a book of commendable scholarship. I cannot recommend it enough.’

Fergal Keane

‘Having played against Rosslyn Park Rugby Football Club over the years, you always got the impression of a friendly, welcoming club with a great history. (Stephen Cooper has written) … a book of beauty and sadness about fifteen men who lost their lives for their country in the Great War. People use the word hero to describe sportsmen but the guys in this book are true heroes. A fantastic and inspiring read from the first page to the last.’

Jason Leonard, England & British Lions

‘This is a portrait of an age where boys grew to be men driven by certainties, where today we have only doubts. And for those certainties they fought and died. Sensitive, original and profoundly moving’

Anthony Seldon

‘A fitting tribute not simply to 15 individuals cut down in their prime, but a paean to all those who died in the First World War’ –

Mark Souster, The Times

‘An inspired idea … brings home the pathos of these ardently lived lives … An original and illuminating approach to this endlessly fascinating subject.’

Edward Stourton

FOREWORD

I was delighted to be asked to write the foreword to this excellent book.

While our armed forces are currently engaged in Afghanistan and previously in Iraq, we should also remember the hundreds of thousands before them who gave their lives in the Great War just a two-hour car journey from Calais or a sea voyage away in Turkey or Mesopotamia.

Stephen’s book tells the story of that war through the lives of one rugby club’s players all sadly lost in those four years.

I hope you enjoy the book as much as I did.

Bill Beaumont CBE DL

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Like the best rugby victories, the researching of this book has been a team effort. The stories of these men could not have been written without the willing help, encouragement and detailed knowledge shared by a host of teammates.

Above all my appreciation goes to Richard Cable, who kicked off the original research and made the first hard yards. Without him this book would not be.

It is my fortune and privilege to have been granted access to personal papers, photographs and memories by family members. My grateful thanks, in chapter order, go to: David Byass and Patricia Moorhead (Alec Todd); Tessa Montgomery (Guy du Maurier); John Bodenham of Floris Ltd for the letters and diary of his namesake; Edward Bodenham for his help with the photographs; Ann Gammie, John Gay, Richard Gay, Peter Lucas and Paul Blunt (Wilfred Jesson); Sir Jeremiah and Charles Harman (’Uncle Jack’ Harman); Eileen Laird, who completed the photographic jigsaw with Robert Dale; and Jimmy Button for material on his Great-Uncle Charles.

Through the miracle of the internet the kindness of strangers has furnished me with many details great and small, but always significant to an author groping blindly into the past. I cannot do justice to them all, but must mention in dispatches the following: Pam and Ken Linge, Andrew Birkin, Paula Perry, Charles Fair, Dominic Walsh, John Hamblin, Bill MacCormick, Jimmy Taylor, Linda Corbett, Michael Parsons, David Huckett, Gavin Mortimer, Jeremy Banning, Philip Barker, Ruaridh Greig, Merv Brown, Mark Bazalgette, Paul Reed, Anne Pedley, Russell Ash, Nick Balmer, Paul Wapshott, Gwyn Prescott, David Lester, John Lee, Ajax Bardrick, Ray Smith, Nigel Marshall, Brian Budge, Alexander Findlater, David Grant, Ann Willmore, Tim Fox-Godden, Lawrence Brown, Charlotte Zeepvat, and John Lewis-Stempel.

A host of archivists and historians have been unfailingly patient and helpful with my enquiries. First amongst equals is David Whittam, tireless archivist and stalwart at Rosslyn Park FC, but deserved gratitude also goes to: Simon May and Alexandra Aslett of St Paul’s school; Vernon Creek at the RAF Museum; David Underdown at Kew; Dr Frances Willmoth of Jesus College, Cambridge; Emma Goodrun and the provost and fellows of Worcester College, Oxford; Christine Leighton of Cheltenham College; Toby Parker of Haileybury; John Malden, Old Dunelmians archivist; Dave Allen of Hampshire CCC; Jim Graham, Donna Jackson and Anne White of TAS; Alastair Robertson of the Alston Historical Society; Sharon Maxwell of the NRCD, Guildford; Michael Harte and Heather Woodward of Wadhurst Historical Society; Julian Reid, archivist of Merton & Corpus Christi Colleges, Oxford; Janice Tait at the Tank Museum; Jonathan Smith of Trinity College, Cambridge; Stuart Eastwood at Cumbria’s Military Museum; Judy Faraday and Linda Moroney of the John Lewis Partnership; Kate Jarvis, Wandsworth Heritage Service; Katie Ormerod, St Bart’s Hospital; Tracy Wilkinson, King’s College, Cambridge; Elizabeth Stratton of Clare College; Anselm Cramer of Ampleforth Abbey; Sue Chan, National Library of Australia; and Katherine Lindsay at the Oxford University Great War Archive.

Additional help and photographs have been kindly provided by Rosemary Fitch, Francis de Look, Chas Keyes, Robert Smith, Peter Bradshaw, Carole Cuneo, Peter Walker, John Black, Ian Lewis, Louise Lawson, Stephen May, Barbara Evans, Nik Boulting, Jenny Hopkins, Ian Metcalfe, Francesca Hunter, Andrew Dawrant of the Royal Aero Club Trust, Christine de Poortere and Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity.

My gratitude is also due to the staff at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, National Archives, British Library and Imperial War Museum. These national treasures deserve all possible recognition and support. Also to Alison McDonald of Richmond Libraries for her persistence in tracking down obscure volumes in the lending system. Another man-made wonder is Chris Baker’s website, the ‘Long, Long Trail’ with its associated Great War forum, an online meeting house and depositary for knowledgeable enthusiasts, many known to me only by their nom de guerre. My grateful thanks to all who freely helped and encouraged.

My thanks also to my classical authority Andrew Maynard, to my Australian correspondents, Ian Johnstone and Michael Durey, and to Major General Dair Farrar-Hockley MC for their unflagging enthusiasm. Merci mille fois à mon copain rugby, Frédéric Humbert.

To Penny Hoare for starting me on the road to publication and to Jo de Vries, Chrissy McMorris and the team at The History Press for the map and driving lessons.

For permission to quote from their copyright work, my thanks to Bill MacCormick, Paula Perry and The Rifles Museum, Paddy Storrie, Stuart Eastwood at Cumbria’s Military Museum, Colonel Tim Collins, Charles Fair, Robert Kershaw, Paddy Storrie, and Chris Myers.

For Faber & Faber Ltd for permission to quote from the letters of Rupert Brooke.

Quotations from Vera Brittain are included by permission of Mark Bostridge and Timothy Brittain-Catlin, Literary Executors for the Estate of Vera Brittain 1970; quotes from George Orwell’s Animal Farm and England, Your England And Other Essays are reproduced by kind permission of Bill Hamilton as the Literary Executor of the Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell; from Journey’s End by permission of the Estate of R.C. Sherriff; from The Burgoyne Diaries with permission from Thomas Harmsworth Publishing Company; from Siegfried Sassoon copyright by kind permission of the Estate of George Sassoon. Excerpt from The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway, published by Vintage Books, reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Limited; from Robert Graves by permission of Carcanet Press Ltd. Extract from The Donkeys: A History of the BEF in 1915 by Alan Clark reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop on behalf of the Estate of Alan Clark; also for the extract from White Heat: the new Warfare 1914–18 by John Terraine, on behalf of the Estate of John Terraine.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and the author and publisher welcome correspondence on this matter from any sources where it has not been possible to obtain permission to quote.

It is my hope that I have breathed life back into these players. This book too is a living memorial, which must go on growing; I welcome any further facts about any of the men and apologise where I have drawn conclusions in their absence.

This is a work of personal passion more than historical erudition, and I trust that true historians will forgive me. Where I have consulted experts, they have corrected me. As in my brief and undistinguished playing career, the errors are all mine.

THE FIRST BLOW

When the time came for the whistle to blow they were glad.

The shrill note hung in the damp air and in the moment’s hesitation before they started, all time was suspended and every breath was held. The waiting was finally over and all they had trained for now lay in front of them. Their great game was now about to kick off on this field and their greatest hope was for victory.

The captain looked along his line to the left and right and saw that his men were ready. They had all worked hard for this since training had begun; they were fit in wind and limb, and eager to get stuck in. The mud on their boots, which they never could shake off, no longer felt so heavy.

He had talked to them quietly, each man in his turn; no need for big words as each knew his job and what he had to do. The big men felt strong, relishing the scrimmage to come, their faces set and determined. The faster men were looking to stretch their legs and show their pace in attack. In their eyes, he could see the excitement and the nervousness; no man on his team wanted to let the side down – if they had fears, this was the worst of them.

Most of all they were eager to take the fight to the opposition. This was their first taste of the game. The side they faced was unknown to them, although its reputation was fearsome. Their captain raised his arm to signal readiness, to steady the impatient, and waited for the moment, his own heart battering so loud in his chest he wondered that his men could not hear it.

He placed the whistle to his lips.

And blew.

THE FINAL WHISTLE

This is the story of fifteen men and more who heard that first shrill blast and answered its call to arms; they did not live to hear the final whistle that ended the game.

All were members of one sporting club, Rosslyn Park, then in Henry VIII’s ancient Deer Park in Richmond to the south-west of London. In their youth they flocked together from all parts of the land and from the furthest ends of the earth to play the game of rugby. They stepped forward again in 1914 to fight a war that would last four long seasons.

Some were still in their playing prime; others had long since hung up their boots in favour of gentler pursuits, professions and families. These now took second place to war. The Victory Medal issued in 1919 sought to ennoble this brutal struggle as ‘The Great War for Civilisation’; but these men never wore this medal or celebrated the victory: every one was killed in that Great War.

The whistle marked a beginning, but it also signalled an end: it blew away the old civilisation. On 4 August 1914, western imperial time was divided into ‘before the whistle’ and after – the time before the whistle would never return. This war did not end all wars, as optimists fervently hoped, but it did forever change the world. Combatants and civilians alike knew that they were living through an unprecedented transformation: the breakdown of one epoch and the uncertain stirrings of a new age. Wartime nurse Vera Brittain wrote in 1916: ‘It seems to me that the War will make a big division of “before” and “after” in the history of the World, almost if not quite as big as the “B.C.” and “A.D.” division made by the birth of Christ.’1 It took four years before the final whistle could sound and ‘After War’ time could begin.

The history of these men begins with their names lost in mystery. Rosslyn Park Football Club was established in 1879. In that year of the nineteenth century British soldiers died at Rorke’s Drift; they also fought and died in Afghanistan, as they do again in the twenty-first. For relaxation they played rugby, with rudimentary pitch and posts, shown in a Victorian periodical engraving, at Khelat-i-Gilzai, near Kandahar.2 In 2007 a prince and future vice-patron of the Rugby Football Union (RFU) kicked an oval ball about with his Household Cavalry unit in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. These colour images now flash worldwide on the internet and satellite television – our media have made progress even if our civilisation hasn’t.

In 1914, with a new war looming, Rosslyn Park already had thirty-five seasons of mud on its shorts; successive waves of players had worn its red-and-white hooped jersey and would now don khaki. Any club of young, physically fit men will naturally suffer losses in wartime; those killed in the ‘Second Great War’ of the century, including the Russian Prince Alex Obolensky, the flying winger killed in his RAF Hurricane in 1940, are rightly revered on a clubhouse plaque. But why is there no memorial to its first war dead? Was it somehow lost in the move from Richmond to Roehampton in 1956? A few short miles but a careless slip by clumsy movers and a slab of broken marble consigned in muttering embarrassment to a skip; without a memorial there was no Roll of Honour, no record of the club’s pain and pride.

So began the first work to piece together the list of men who died. The sole clue was a yellowed press cutting of the club’s 1919 annual general meeting, reporting sixty-six members killed and six missing. No names were mentioned. Thankfully the club’s membership records survive; the meticulous copperplate entries for name, address and school attended were checked against Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) records of those who died.3 Some names took several more hours of trawling through census, school and university records, newspaper microfiche and National Archives to achieve conclusive matches. The total has already surpassed the stated seventy-two;4 several more sit ‘on the bench’, tantalisingly short of the perfect match of name, address or initial that would select them definitively for the side lost by history.

Many names were already linked through shared friendships at school and university. In varying permutations, they bob to the surface time and again in a stream of match reports, school magazine articles, team sheets and photograph captions. Rosslyn Park would unite them again – friends naturally flock together in rugby – and prolong those masculine bonds into adult life. So, fleetingly, would military service in war, until it tore their brief lives and friendships violently apart. Muscular rugby bodies were reduced to sandbags of body parts: lungs drowned in gas froth; tendons and ligaments shredded and twitching; limbs sheared and snapped by pressure waves from passing shells; skulls splintered by steel, stripped of flesh and bleached. In their hour of dying their median age would be 23.

Young men, whether from the Australian outback, Indian railway or industrial Wales, were drawn by education or profession to London’s metropolis and found companionship there with like-minded rugby players; they became teammates and close friends. Some passed through the club only briefly for a season or two and might not recognise a common allegiance if they later stumbled across a fellow ‘Park-ite’ at the front. Guy du Maurier had first played for the club in its earliest North London incarnation, when just 16 in 1881; he became the oldest to die, aged 49, in 1915. Much younger men than Guy were looking forward to a new season and a life of promise when war broke out; the youngest, Gerald David Lomax, was to die at just 20 years of age.

Some displayed exceptional talent in sporting arenas (not just the rugby field) that won them national honours. Others discovered talents and passions they scarce suspected – among them a poet and a playwright – to confound those who cherish the fixed image of rugby ‘hearties’ who could destroy Christopher Isherwood’s college room for kicks. Some achieved distinction in death: the first player lost in August 1914 was the first airman downed by enemy fire; one of the last won the Victoria Cross in 1918. Many more were unsung battlers who hardly aspired to international sporting glory but volunteered enthusiastically to represent their country in the field.

Perhaps these players had absorbed some martial spirit from the terroir of Richmond Old Deer Park, in the manner of fine French wines. The ‘splendidly quick-drying springy turf’5 had once been used as an archery range by Queen Elizabeth I, that ‘weak and feeble woman, with the heart and stomach of a king’. Just as these fresh recruits came from all corners of Britain and the empire for trial on the rugby field, so they were sent out to fight in every theatre of this war. On its second day the writer Henry James could write privately of ‘the plunge of civilisation into this abyss of blood and darkness’;6 public hubbub, on the other hand, was of heroic adventure. The early clashes, roared on by armchair spectators reading sanitised match reports from the battlefield, had the flavour of one huge game. Plucky defence to the last man against superior opposition, defiant goal-line stands and, in true sporting headline fashion, the ‘Race to the Sea’, as both sides attempted to outflank the opposition by running wide around the wings.

A series of last-ditch tackles, at the cost of thousands dead and wounded, stopped every attack until the Germans were squeezed out of play at the topographic touchlines of the North Sea and Swiss border. Both sides then settled down to a full-frontal forwards game in the mud, rolling on interminable replacements as men went off injured and dying. The thoroughbreds were forever left in reserve, starved of action, waiting for the opportunity to burst through a gap in the opposition line which, in those four hard years, only appeared very late as its German defenders died on their feet – or surrendered on their knees.

However, the stark image of the Western Front is only part of the story. What emerges from the lives of these rugby men is a remarkable history in miniature of the entire war, across all fronts, arms, theatres and engagements. Some went to ‘quiet shows’ that proved just as deadly as the celebrated set pieces of Ypres and the Somme. They would die in Dublin and Lincolnshire. Some were honoured for their bravery, with one achieving the nation’s highest award; far more fought in obscurity, their feats of arms rarely recorded and their death in ‘some corner of a foreign field’ marked only by the prosaic marginal notes of overworked War Office clerks. Not for them the gleam of the Military or Victoria Cross, or even the dignity of a named grave, only the shadow of the Cross of Sacrifice or granite memorial.

Some inherent quality of bravery or natural leadership saw many rugby men take the lead, as they had on the field, whether as reckless pilots in frail biplane or balloon, as officers of doomed infantry companies or at the head of desperate naval storming parties. Youthful hopes – the promise of life, adventure, love – turned swiftly to fears of death, dismemberment, squalor and insanity. In callous mockery of the club motto, fortune did not always favour the brave.

Their names are now scattered on public war memorials in home towns where they lived and were loved, and on battlefields where they perished. They were also engraved on the rim of the Victory Medal, its rainbow ribbon emptily promising ‘never again’. This award was not automatic; service medals were issued to other ranks, but officers or their next of kin had to apply for them. The family also received a circular bronze plaque, known blackly as the ‘Death Penny’, and a printed scroll from the king. These too are scattered or lost. I have been privileged to view the plaque and medal trio of ‘first-class rugby forward’ Arnold Huckett, dead at Gallipoli, touchingly reunited by a collector with those of his brother Oliver, killed in France. Aussie Syd Burdekin’s medals are safe in a Sydney museum. As for the rest, who knows.

For many parents, the loss of a young son (or two, even three), heart-breaking in its own right, could also mean the death of the family name, as the male lineage was violently severed. Thus it could be said that whole families died at Ypres, Suvla Bay or Kut. Kipling borrowed from Ecclesiasticus to promise that ‘their Name Liveth for Evermore’, but with no descendants to preserve them, the living stories behind those dead names have rarely been handed down. Nor are they collected in one place that unites them, as the rugby club once did. Occasionally photographs emerge from family albums that speak more eloquently than the formal portraits in memorial books. However, some sons have left no trace of a face and remain invisible and lost as men. It is the author’s hope that more knowledge will rise from the depths when readers chance upon these pages.

Almost a century later, why do we write so many books about the Great War? And why do they invariably focus on those who died? Gertrude Stein’s oft-quoted ‘lost generation’ referred not to the dead of the war, but to its war-interrupted survivors, damaged and drifting in the 1920s. Many died but three-quarters of Park’s estimated 350 members who fought came through alive, although not always untouched in body or mind. There are as many heroic stories to be told of players who survived. In his 1918 VC citation, Captain Reginald Hayward:

… displayed almost superhuman powers of endurance. In spite of the fact that he was buried, wounded in the head and rendered deaf on the first day of operations and had his arm shattered two days later, he refused to leave his men, even though he received a third serious injury to his head, until he collapsed from sheer exhaustion.7

In hearty disregard for mortality, the superhuman Hayward lived until 1978. Yet it is Arthur Harrison VC, who died sixty years earlier in a storm of bullets at Zeebrugge, who fascinates and whose equally vivid story is told here.

This book tells of fifteen lives cut short, and touches on many others. Few of these mostly young men had time to marry and father children who would live after them and tend the flame of memory. If they wrote letters home, as surely they did, only a few have been spared by time; those glimpses into the thoughts of Alec Todd, John (Jack) Bodenham, Jimmy Dingle and Guy du Maurier are precious. Many did not even leave mortal remains: thirty-four bodies – two entire teams and more – were never found and have no known resting place. The only true death is to be forgotten; these pages hope to resurrect the ghosts of men lost and buried in the mass tomb of the Unknown Soldier that is the Great War.

A fortunate few achieved some small measure of youthful fame before the whistle, but rarely did it last, overwhelmed by the cataclysmic wave that washed away their world. None lived to write the memoirs and autobiographies which flooded on to the market in the 1920s and by which we know of the survivors’ experiences. None were interviewed as forgotten voices in their declining years by historians rushing to preserve their accounts before the virus of death deleted them. While their names crumble on cold monuments, the warm-blooded stories of these vigorous, energetic and talented rugby-playing men have never been told.

Until now.

THE BOYS WHO WON THE WAR

Soldiers do not start wars. They fight them under orders. It is politicians who start wars and leave soldiers to endure them until they end. Then in the ‘Great War to end all wars’, once the fighting had stopped, the politicians again stepped forward, flags flying, to create the Treaty of Versailles and its vindictive reparations against Germany which led inexorably to another great war. And so it goes.

This fight was one of attrition. The generals’ dreams and experience lay in wars of movement: sweeping flanking manoeuvres and gallant cavalry charges against brave but poorly equipped adversaries in colonial campaigns. Once outflanking was blocked by trenches stretching 460 miles from the Channel to the Alps, they had no Plan B. Gallipoli and Mesopotamia represented flanking moves on a grand scale, but soon regressed to the unimaginative mean of Western Front siege warfare.

Troops battered themselves senseless and lifeless against enemy defences because of the generals’ instinct to attack, to break through and renew mobile warfare – otherwise why have generals? Even if there was no strategic offensive, there was an insistence on ‘activity’ or demonstration of aggressive intent, with artillery ‘hates’ and trench raids by night and day. The question ‘Are we being as offensive as we might be?’ was deservedly satirised in the pages of the Wipers Times trench journal; offence simply brought counter-offence, bombardment and death.

The presumption of attack created the trench conditions suffered by the British in cold Flanders mud, Turkish scrub and Mesopotamian sand. If victory was just over the ridge (and at least three cunningly laid and strongly built defensive lines) then why build permanent trench systems? So reasoned the generals. There was no need for fortification or durability according to the Field Service Pocket Book: ‘The choice of a position and its preparation must be made with a view to economising the power expended on defence in order that the power of offence be increased.’ So while the Germans on the Somme could emerge unscathed from their concreted bunkers after seven days of artillery barrage, the British crouched in dugouts, or ‘funk holes’, scraped into the trench wall and occasionally covered with thin sheets of corrugated ‘elephant iron’.

Germany had swiftly taken territory in France. With her eastern front competing for resources (and, in the view of the High Command, more likely to bring a result over Russia), she was content to hunker down in well-engineered defensive systems and let machine gun, gas and wire do the job. The British attacked time and again, while the Germans simply bided their own time and quickly counter-attacked. From September 1914, when the French turned them back within sight of Paris, to the desperate last fling of spring 1918 which so nearly succeeded, the only sustained German attacks were at Second Ypres and on the French at Verdun. Even there the objective was not breakthrough but bloodshed – to ‘bleed the French Army white’ – knowing that France would never relinquish this symbolic fortress.

Untroubled by any obsession with attack, Germany made tactical withdrawals to better positions, like the Siegfried Line in 1917. British line officers like du Maurier could see the wisdom of such flexibility as early as February 1915 when trying to protect the indefensible trenches east of Ypres. However, Field Marshal Haig, faced with the 1918 German offensive, could still issue his famous Order of the Day on 12 April mandating that ‘every position must be held to the last man. There must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one must fight on to the end.’

It was attrition, economic and military, that won the war. The Royal Navy’s blockade finally choked the German people and war machine into submission. Germany’s response of unrestricted submarine warfare only served to bring America’s might and manpower into the war in 1917. What allowed the Allies to stay in the war so long despite appalling losses, however, was the dogged persistence of troops fed in successive waves into the maw of the guns. They came from all over France, Britain, its empire and dominions and, eventually, its former colonies in America. They rarely saw the generals and visits by staff officers wearing the ‘Red Badge of Funk’ on collar tab and cap band were brief. Lieutenant General Sir Lancelot Kiggell famously burst into tears when first confronted with the Passchendaele battlefield from his staff car, blurting, ‘Good God, did we really send men out to fight in that?’ He was assured it was much worse further up. Military discipline required that line officers showed strict public respect; in private they could be scathing and the men more openly scornful. What kept them fighting for four long years was those line officers, greatest in their number the young subalterns fresh from school or university. These were the boys who won the war.

Poet Sir Henry Newbolt believed that Clifton (Haig’s school) gave boys the ‘virtues of leadership, courage and independence; the sacrifice of selfish interests to the ideal of fellowship and the future of the race’. It was good form ‘to be in all things decent, orderly, self-mastering: in action to follow up the coolest common sense with the most unflinching endurance; in public affairs to be devoted as a matter of course, self-sacrificing, without any appearance of enthusiasm’. Christian schoolboys happily took classical pagans as role models to become ‘the Horatian man of the world, the Gentleman after the high Roman fashion, making a fine art, almost a religion of Stoicism’.1 Their learning commanded respect from those with little or no education. Schooling had prepared them for a life of service to empire or business. Profession or family background gave them the authority of gentlemen over commoners, an order then accepted as entirely natural and certainly necessary for military discipline. They were mostly young (but not always, as we shall see), brought up as decent, compassionate men, with clear values of chivalry, godliness and sportsmanship that intermingled. This seems almost incomprehensible now in our hardened and questioning age. They had certainties where today we have doubts.

Guy du Maurier, a professional commanding a fusilier battalion said of one exemplary subaltern, a gentleman amateur: ‘Absolutely no previous training as a soldier is wanted at this game – only a stout heart – a grip of men and a calm cheerful nature.’ If their relationship to authority – whether house, school, regiment, king or country – was one of unquestioning obedience, then these boys also took thoughtful responsibility for the men on their team and felt genuine obligation towards those less privileged than themselves. Arguably, war exposed them as never before to the lower classes and trench life had a levelling effect. Energetic and youthful, they led enthusiastic games of rugby or football to keep up morale and break down social barriers. Many had flaws and weaknesses, if only from inexperience, which war would magnify and sometimes fatally expose, but they played the game as best they could. There were more Stanhopes than Flashmans.

These line officers shared dismal living conditions, starving for days with their men, carried the same weight of equipment and fought bravely alongside them. Witness how many rugby-playing officers receive fatal wounds to the head; they were shot peering over parapets, leading raids, or picked off by snipers when checking on their men. They were the first over the top in attack, their well-cut uniforms standing out from the baggy, shapeless Tommy to mark them as primary targets. As honorary horsemen – even in infantry regiments – they wore leather belts, boots and tight riding breeches. German snipers were instructed to target the soldiers with ‘thin knees’; once the leaders were cut down, they were told, their men – who were not trained professionals like the Germans – would be lost in headless confusion. The officer casualty rates of 1915 were nearly double those of other ranks; if honoured to serve with the regular regiments, which were thrown into every important attack, junior officers could expect six weeks at the front before being wounded or killed.

Private soldiers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) felt for their ‘young gentlemen’ a genuine, unashamed affection that crossed the class divide. Their letters of condolence to bereaved parents of junior officers may trail the stock phrases coached by chaplains in their pragmatic ministering (when talk of God might fall on deafened ears), but no more so than their educated officers, who invariably ‘cannot tell you how deeply I feel his death’. As censors reading letters home, subalterns learned to understand – and share – the intimate hopes and fears of men they would never meet in peacetime. The servant valet was retained even under battlefield conditions as a comforting reminder of the peacetime class structure; his main role was to maintain a reasonable table and standard of dress for his officer. Of Charles Alvarez Vaughan, winger for Park, Surrey and the Barbarians, killed at Loos, his servant wrote:

I never served a better Officer. The morning of the attack he went round his Platoon as cool as if we were on parade, giving them all a cheery word, and there was not one of them that morning but would have done anything for him, for they always declared that he was the best little Officer in the Battalion … We knew he was offered leave just before the attack came off, but he refused, he said he would take it after we were relieved, and I can assure you his Platoon were proud of him, as the Jocks say, ‘he was the best wee spud that ever wore a kilt’.2

Vaughan remembered his man, Private Robert Ireland, in his will; the money from the ‘young master’ was gratefully sent to his sister. Even the statements dragged out of damaged memories for later Courts of Inquiry bear witness to the mutual respect of decent men and their line officers, united in common vulnerability under threat from bullet, bomb and bayonet. Lieutenant Dingle at Gallipoli, in the highest form of shared English humanity for his men, was ‘a gentleman and made tea for ten of us’.

Did a generation truly die? The myriad names at Thiepval or Tyne Cot and the memorial on every village green might persuade us so. Of 8 million who served, some 723,0003 died, of which half a million were under 30. Census returns in 1921 showed a 14 per cent decline since 1911 in males of military age, with the influenza epidemic of 1918 playing its own deadly part. Upper- and middle-class officers suffered disproportionate war casualties. So, accordingly, did the rugby clubs: of Park’s men who marched away, a quarter failed to return4 – a heavy blow on a single club. However, glance at the roll of pre-war Barbarians in Wemyss’ history5 and the black cross of sacrifice is only lightly sprinkled over its index. The scale of the slaughter is undeniable but men did survive in surprisingly high numbers, albeit many carrying wounds physical and psychological into their post-war lives. Some, unable to find adequate words or simply unwilling to discuss the horrors with anyone who had not been there, would become strangers in their own families.

In close communities which had joined up en masse in 1914, the death toll was so high that it would indeed have felt like a generation wiped out. The Pals battalions rushed to war from factory towns in a wave of patriotic fervour and workers’ friendship. Complete new service battalions were drawn from city districts, like the Blackheath and Woolwich (20/London Regiment), or from common pursuits, like the Sportsmen’s Battalion (23/Middlesex). One May morning in 1915, twenty-five men from the village of Wadhurst in Sussex were killed at Aubers Ridge; among them, Roy Fazan, who had played rugby in Germany with Park two years earlier. His brother and fellow clubman, Eric, survived the massacre to record in his diary: ‘About mid-day the CO [commanding officer] told me poor Roy was killed … All poor old Roy’s men say he was very cool & shouted “come on boys”.’6

Then there were the public schools. After a shaky, sometimes violent start to the nineteenth century, they became ‘Builders of Character by Appointment to the British Empire’. The Clarendon Commission of 1864, set up after widespread criticism of the public school system, declared:

It is not easy to estimate the degree in which the English people are indebted to these schools for the qualities on which they pique themselves most – for their capacity to govern others and control themselves, their aptitude for combining freedom with order, their public spirit, their vigour and manliness of character, their strong but not slavish respect for public opinion, their love of healthy sports and exercise.

Previous wars, or at least the Battle of Waterloo, according to the victorious Wellington, had been won on the playing fields of Eton. Of 5,650 Etonians who served in this war, 1,157 were killed. Quick to join up in August 1914 or already commissioned, the flower of Etonian youth from the best families was crushed in the brutal first months. Peers and baronets fell like titled ninepins. So great was this toppling of sons of the ruling classes that Debrett’s was unable to publish an updated edition in spring 1915.

Eton, however, was (and is) untypical even in the public school system of the age; Victorian Britain needed more than landed gentry with fluency in Latin and Greek. The rapid expansion of the empire required increasing numbers of trained military leaders, colonial administrators and civilising missionaries. With one exception (and that a brief one), Rosslyn Park players were not sons of Eton, but drawn from the industrious and professional middle classes, sons of doctors, lawyers, bankers, teachers and even (whisper it softly) men in trade. By the early twentieth century, birth and breeding were just one part of an evolving class structure that would undergo its most radical transformation as a result of war. Fifteen of the eighty-odd who died were sons of clergymen who lived on the verge of poverty, sustained by their vocation and the moral leadership of their flock. In this war, this would be as good an example as any military academy could give.

These boys attended the host of ‘new’ public schools that had flourished since Clarendon’s endorsement and the founding of the Headmasters’ Conference in 1860. Old Etonian George Orwell noted: ‘At such schools the greatest stress is laid on sport, which forms, so to speak, a lordly, tough and gentlemanly outlook.’7 When these boys left school and university they generally worked for a living, often following in fatherly footsteps. Through tribalism and tradition more than locality, certain schools dominated Rosslyn Park’s membership: Bedford, Marlborough, Haileybury and Uppingham. Schools were recorded in the membership ledger as irrefutable proof of a ‘fit and proper person’ (and invaluable help to this book). They still appear on the club’s honour boards; a continuing tradition in changing times where the late, great Andy Ripley’s Greenway Comprehensive now rubs shoulders with Marlborough and Uppingham.

These boards are a mournful register of schools which racked up losses to stretch comparisons with cricket scores and matched Orwell’s observation that at public schools ‘the duty of dying for your country, if necessary, is laid down as one of the first and greatest of the Commandments’.8 One in three Haileybury boys entering the school between 1905 and 1912 died in the war. There were 447 lost from Uppingham, whose alumni could easily have formed a ‘pals’ side at Park and make up fully a quarter of its roll call of dead. Its headmaster, lacking prescience, was a vocal hardliner, pronouncing: ‘if a man can’t serve his country, he’s better dead.’9 Schoolboys at Charterhouse today know there are as many in statu pupillari as names (686) engraved on the walls of its Gilbert Scott-designed memorial chapel. Wellington lost 699 alumni, Dulwich, 518, and Marlborough, 733. These birds of a social and educational feather later flocked together as students at Oxford, Cambridge, Sandhurst and the London teaching hospitals, where most first played for the club which binds their lives and early deaths into this volume.

Many became leaders at an early age: Jimmy Dingle and Nowell Oxland at Durham, Arnold Huckett at St George’s Harpenden captained their school. Dozens more led the XV or XI, or both. Invariably their sporting prowess and leadership qualities brought them to the first rank of their school’s Officer Training Corps (OTC). In 1804, well before its eponymous football game and Tom Brown, Rugby School formed a volunteer force to repel Bonaparte from Warwickshire. The spoilsports Nelson and Wellington ensured that it was not called into action and public school OTCs only started in earnest in 1860 when Rugby, Rossall, Eton, Harrow, Marlborough and Winchester all begat rifle corps. The Boer War and breathless tales in the Boys’ Own Paper (like Park, first opened in 1879) and its legion of imitators gave OTCs a major boost. Haldane incorporated them into his Army Reforms from 1908; by 1911, 153 schools had them and 100,000 of some 250,000 officers commissioned in wartime had passed through an OTC.

By 1909 half of Harrow’s boys were in the corps, its headmaster urging parents that ‘attendance at Camp is a real engagement demanded of them, not a mere school matter, but as a duty to their country’. Objectors at Marlborough, noted poet Charles Sorley, were barely tolerated and ‘inevitably come in for a certain amount of chaff as mere civilians’. By June 1914, Westminster was even more emphatic: ‘it is the duty of every able-bodied cadet to consider seriously whether he cannot give up a small part of the holidays to maintaining the honour of the School, even at some slight personal inconvenience.’10 Many boys continued after school, enlisting at university OTCs or in pre-war military, sporting and social ‘gentlemen’s clubs’ like the Inns of Court, Artists’ Rifles or London Rifle Brigade on Bunhill Row, which charged a guinea subscription.

The bolt of war hardly strikes out of the cloudless blue of August 1914; there had already been a decade of fevered speculation in parliament, the press, theatre and popular fiction. However, outside the small, well-trained regular army and in the absence of conscription, the best prepared to fight this war were those who had long been schooled for it. Vera Brittain, writing fifty years after the war that buried both her fiancé and brother, still hears an abiding echo:

… of a boy’s laughing voice on a school playing field in the golden summer. And gradually the voice becomes one of many; the sound of the Uppingham school choir marching up the chapel for the Speech day service in July 1914, and singing the Commemoration hymn … there was a thrilling, a poignant quality in those boys’ voices, as though they were singing their own requiem – as indeed many of them were.11

Their names, picked out in gold leaf for scholarships, team captaincies and school prizes on mahogany boards, appear but a few years later carved on chapel walls or crosses on village greens. Just as poignant are the boys in their thousands who won no distinction at school, but are honoured on their war memorials.

At these highly competitive schools, alumni in wartime service were garlanded with acclaim, much as prestigious university entrants are today. Many used precious time on leave to visit the institution they had only just left and which still dominated their social circle. But these triumphal returns soon diminished. The school magazine edged in black its lengthening lists of names under the heading ‘Pro Patria’ yet lauded its fallen champions, thereby guaranteeing a succession of classmates moving swiftly from sixth form into uniform, through the trenches and into communal or unmarked graves.

In October 1915, Westminster proclaimed 930 Old Boys serving or already killed and swelled with satisfaction: ‘It is a record of which we may be justly proud, for it should be remembered that Westminster, which has contributed more than three times its own size, is the smallest of the great Public Schools, and that not more than about eighty Old Westminsters were in the Regular Army when war was declared.’12 Editors’ sentiments and language were identical wherever public school values flourished, from English shire to rural New South Wales. George Llewellyn Davies, nephew of Guy du Maurier (and model for Peter Pan), was swiftly ushered into a king’s commission on the strength of his knock of 59 in the Eton v. Harrow cricket game at Lords three years earlier, recalled in admiration by the recruiting colonel at his interview. These lost boys might also have heard Wendy’s words: ‘Dear boys, I feel that I have a message for you from your real mothers, and it is this, “We hope our sons will die like English gentlemen”.’

In the dubious judgement of the War Office, these youngsters had the right family and school background, strength of character and sufficient OTC experience to lead men to war. Those without the privilege of public school education faced a barrier. Kingston Grammar School product R.C. Sherriff wrote later of his first encounter with the recruiting office:

An officer, I realised, had to be a bit above the others, but I had a sound education at the grammar school and could speak good English. I had had some experience of responsibility. I had been captain of games at school. I was fit and strong. I was surely one of the ‘suitable young men’ they were calling for.13

However, the future author of Journey’s End was rejected, an experience which surely tinged his portrayal of Raleigh and Stanhope. Pragmatism and the butcher’s bill soon overwhelmed class prejudice; the events in France that he dramatised in his 1929 Savoy Theatre hit meant he did not have to wait long for his commission. Conversely, many of the predestined ‘officer class’ were less fussed about status and only too happy to join the ranks in their haste to reach the front.

Britain’s regular army was some 250,000 strong at the outbreak of war. Tiny by conscripted European standards (4 million Frenchmen and 5 million Germans), it was further weakened for a continental war by one battalion in each regiment being stationed overseas to guard the outposts of the furthest-flung empire the world had seen. South African war veterans like Lord Roberts had ardently lobbied for National Service, but to no avail. The Army Reserve – men who had served time with the colours and could be recalled in time of war – numbered some 213,000 former officers and soldiers of varying ages, many without experience of fighting. The part-time Territorial Force, established by Haldane, was viewed with suspicion by some, notably Lord Kitchener: they were ‘Saturday soldiers’ who had signed up for home defence only, with a clause that specifically precluded them being posted abroad, and were thought unreliable when the chips were down.

Many Park players had joined a Territorial regiment in readiness for hostilities that were, in most minds, simply a matter of ‘when’, not ‘if’. Other ranks had more straightforward motivations. The 10/London (Kensington) Battalion was packed with men from grand department stores like Derry & Toms and Barkers; the regiment was a social extension of their workplace and the only means to weekend camps and paid annual holiday. Most ‘Terriers’ volunteered for service overseas in 1914, but not all; while Robert Dale’s 1/9 Manchesters fought, the 2/9 stayed at home in training, until conscription took away any choice. Few who opted for active service received the full six months of training they were promised.

In England’s July sunshine, a shadow fell across Territorial, OTC and corps summer camps, as regular army instructors and cooks suddenly departed. Newspaper headlines cast doubt over a 1914/15 rugby season; many players, itching to get into training, wasted no time in joining up for the new adventure – many Parkite applications were signed in the early days of August. There was real fear that the affair would be over before they reached the front; God had matched them with this short hour and they were dashed if they were going to miss it.

On 7 August, Lord Kitchener pointed his finger from that celebrated poster and called for men aged 19–30 to join up. These would be the ‘First Hundred Thousand’ (or K1) of the million men he envisaged being needed for ‘three years or the duration of the war’ in his New Army, quickly known as Kitchener’s Army. Innocent boys in their teens and indignant men over 30 tried to lie their way in, many with facile success as the recruiting sergeant made another easy shilling. His lordship had his million by the end of 1914 – 1,186,375 to be precise – with over a million more in 1915. In London they flocked to recruiting stations from Dukes Road to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, while some travelled from distant shores to answer the call. After his last Park game in March against Royal Naval College Osborne, Charles Vaughan had shipped out to Colombia to work on his father’s cattle and tobacco estates. Hardly had he arrived than he did an abrupt about-face on to the river steamer from Honda to Baranquilla, starting the long voyage back to take up his post in the Reserve in October.

Such wildly successful recruiting brought immediate problems: there were more men than uniforms, equipment or guns. New Army battalions wore civilian clothes, or the embarrassing early dress of bright blue, with broom-handles and pitchforks at the slope. Officers for these ramshackle ranks were in even shorter supply. Indian army men home on leave, like Major Jonathan Bruce, did not return to their experienced battalions, but were requisitioned for novice units. Retired officers in their forties, like Alec Todd, returned to the colours. Students and schoolboys swapped one uniform for another.

Some older chaps, ‘between thirty and thirty-five, absolutely fit and game for active service’, wrote to The Times on 26 August, demanding an elite contingent be established entirely from public school and university-educated men. They met at Claridges (where else?) to draw up their proposal to the War Office, being ‘anxious to serve their country, but at the same time somewhat chary of joining the regular army with the ordinary run of recruits’. The University & Public Schools (UPS) Battalion protested that:

There is no trace of snobbishness. Everyone accepts he is merely a ‘Tommy Atkins’ and is proud to be one. The reason for forming battalions of ourselves is esprit de corps. Every man will remember his old school, and do his utmost to keep it level with the others in this undertaking.14

Nonetheless this war was as much about upholding the honour of the schools as king and country – and those fellows from St Cakes couldn’t be allowed to steal a march.

Certainly the army had a familiar feel for many former public schoolboys. Sassoon’s alter ego, Sherston, found that being in the army was very much like being back at school. Charles Sorley, another Marlburian and angry critic of war from the outset, remarked that his Suffolk regimental colours matched his school house’s. Absurd rules, ill-fitting uniforms with discreet badges of status, harsh discipline and compulsory exercise were nothing new; even the food harped back to the refectory. Many ex-schoolboys were delighted to be back in a regime where individuality was suppressed in favour of conformity and where routine duties banished the uncomfortable freedoms of adulthood. Rifleman Jack Bodenham positively enjoyed the refuge from responsibility afforded by private soldiering in the ranks – his diary shows him perfectly content as ‘one of the lads’. But the great majority willingly took a commission in His Majesty’s army, happy to be prefects once again.

Sherriff, who initially resented the public school exclusion zone, was eventually magnanimous. The testimony of one who was at the Somme and Ypres and won the Military Cross is worth that of many latter-day armchair historians and academics. He judged that:

… most of the generals had been public schoolboys before they went to military academies. They knew from firsthand experience that a public school gave something to its boys that had the ingredients of leadership … Pride in their schools would easily translate into pride for a regiment. Above all without conceit or snobbery, they were conscious of a personal superiority that placed on their shoulders an obligation towards those less privileged than themselves. All this, together with the ability to speak good English, carried the public schoolboy a considerable way towards the ideals that the generals aimed at for good officers.15

In his view, it was the line officers’ achievement to sustain a fighting force that would soak up punishment for four whole years until the weakened opponent was too exhausted and demoralised to carry on. Ranker Alfred Burrage concurred in his memoir: ‘I who was a Private, and a bad one at that, freely own that it was the British subaltern who won the war.’16 As nervous conscripts young and old latterly replaced volunteers in their prime who had been obliterated, damaged or driven mad in the first two years, these officers’ humane compassion and sense of responsibility led them to take care of the men in their charge.17

British officers averted the widespread mutinies that almost derailed the French Army in 1917, saw Italian mass desertions after Caporetto and the catastrophic collapse in German morale of 1918 ‘by keeping the men good-humoured and obedient in the face of their interminable ill treatment and well-nigh insufferable ordeals’. The headmaster of Cheltenham College went further: ‘They have led them like faithful and good shepherds, caring for their souls and bodies, tending them, helping them and laying down their lives for them. They have loved their men and their men have loved them.’18

Companionship, fatalism, tobacco and the rum ration played supporting parts. Individuals had bitter personal experiences, of which they later wrote vividly, but the morale of the team – from platoon to division – remained steady and resilient, apart from an isolated late wobble at Étaples base camp. Sherriff and du Maurier agreed that these officers ‘led them, not through military skill, for no military skill was needed’:

They led them from personal example, from their reserves of patience and good humour. They won the trust and respect of their men, not merely through the willingness to share the physical privations, but through an understanding of their spiritual loneliness. Many of the younger ones had never been away from home before.

Like Stanhope these were the team players, ‘always up in the frontline with the men, cheering them on with jokes, and making them keen about things, like he did the kids at school’,19 even if it was in low murmurs through clenched teeth. Their commissions may have been temporary, but they carried them out with abiding durability. Finally the hour was theirs, in understated British fashion: ‘through their patience and courage and endurance [they] carried the Army to victory after the generals had brought it within a hairsbreadth of defeat.’ Sherriff concluded of these young men: ‘The common soldier liked them because they were “young swells”, and with few exceptions the young swells delivered the goods.’

After all, they had new junior boys to keep in line, new teams to captain, new games to win. They did not yet know about the ‘hell where youth and laughter go’.20

1

CHARLES GEORGE GORDON BAYLY

THE FIRST OF THE GANG

Charles George Gordon Bayly, in Royal Engineers uniform. (Royal Aero Club)

In St Paul’s Cathedral, a boy of 15 pauses before the marble figure of a soldier, laid at rest like a medieval knight. He knows this monument is hollow, empty of its corpse; he gazes in disbelief that this great hero of empire should be his relative, although he has spent his youthful life in the daunting certainty.

The boy stands on the verge of manhood; a distinguished scholar at a famous school, an all-round sportsman with colours in rugby and cricket, and newly enlisted in the Cadet Corps. He is also popular, according to an obituary which the school magazine will print only eight years hence: his ‘pleasant temper and fine character made him a general favourite’. His is the first of 500 such notices published by St Paul’s school.

Today his schoolmates are restive after the underground railway journey that has brought them from their terracotta temple of learning in West Kensington to the great domed cathedral that gave its name to the school. The boys nudge and jostle and exchange knowing looks, daring each other to rib their solemn friend, lost in his reverie. Sensing their amusement, he pulls back his shoulders, lifts his chin and stiffens to attention. His companions hush in shame and sidle away, leaving him alone to muse upon his own destiny.

Charles George Gordon Bayly was born to be a soldier. Named after his famed great-uncle, General Charles George Gordon, he was perhaps equally destined to die a soldier, as his ‘Eminent Victorian’ ancestor had famously done at Khartoum. His military breeding was as impeccable as the naming instincts of his family: one grandfather was Major Neville Saltren Keats Bayly of the Royal Artillery, the other Colonel William Jesser Coope of the 57th Regiment. Their valises were much travelled; the recruiting slogan ‘Join the Army, see the world’ never rang so true as in the Victorian era.