Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

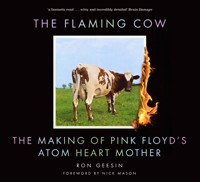

'a fantastic read . . . witty and incredibly detailed' - Brain Damage By the late 1960s, popular British prog-rock group Pink Floyd were experiencing a creative voltage drop, so they turned to composer Ron Geesin for help in writing their next album.The Flaming Cow offers a rare insight into the brilliant but often fraught collaboration between the band and Geesin, the result of which became known as Atom Heart Mother – the title track from the Floyd's first UK number-one album. From the time drummer Nick Mason visited Geesin's damp basement flat in Notting Hill, to the last game of golf between bassist Roger Waters and Geesin, this book is an unflinching account about how one of Pink Floyd's most celebrated compositions came to life. Alongside photographs from the Abbey Road recording sessions and the subsequent performances in London and Paris, this new and updated edition of The Flaming Cow describes how the title was chosen, why Geesin was not credited on the record, how he left Hyde Park in tears, and why the group did not much like the work. Yet, more than fifty years on, Atom Heart Mother remains a much-loved record with a burgeoning cult status and an increasing number of requests for the score from around the world. It would appear there's still life in the Flaming Cow yet.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 133

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE FLAMING COW

To four old friends

and the amusingly forlorn pursuit of truth

Front cover: Atom Heart Mother cover album © Records / Alamy Stock Photo Frontispiece: Cow design, build and torch: by Dan Geesin; photograph by Ron Geesin All Abbey Road photographs: photographer Richard Stanley © Ron Geesin

First published 2013

This paperback edition published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ron Geesin, 2013, 2021

The right of Ron Geesin to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 5180 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Design by Katie Beard

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Nick Mason

Introduction

1 Who Am I?

2 The Lithe Men Come

3 Epic Consultations

4 Pudding Stirred, Oven Ready

5 Pudding Cooked

6 Atomic Dung Flies

7 Damp And Golden Daze

8 La Vache Atomique

9 The Udder View

10 Onward, Dear Mother

Discography

Appendix: Choir List

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Frances Geesin (also known as Frankie or Frank, and she often is): my nearest and dearest; the one who sees.

Joe Geesin: research at the British Library Newspaper Archives, Colindale, London; research of press reports, videos and DVDs; providing discography.

Pink Floyd Music Publishers: information on publishing decisions.

Nick Mason: chats and general support; upholder of healthy humour.

David Gilmour: support for the 2008 revival and four corrections to the original hardback edition.

Jean-Manuel Esnault: bootlegs of The Amazing Pudding and Atom Heart Mother in the BBC ‘Sunday Concert’ with John Peel.

Geoffrey Mitchell: identification of John Alldis Choir members, and new information.

Hervé Denoyelle: the Great French Connector.

Philippe Gonin: the Great French Activator.

Richard Stanley: photographer of the Abbey Road sessions.

Paul Machliss: discoverer of the Hyde Park stage photographs.

Matt Johns: other Floydian connections.

Accademia Musicale Naonis: photographs and posters.

Nick Mason Archive: Saucerful Of Secrets poster.

Pink Floyd Legend (group): photographs.

FOREWORD BY NICK MASON

I find this foreword a little tricky to write. Normally a word or two on the talent and charm of the writer, and a bit about our mutual admiration and a puff for anything I’m flogging myself will suffice – but on this occasion I have to contend with the odd event or comment where it is clear that either I, or my colleagues, have behaved in a less than saintly way – well, in Ron’s opinion anyway – and I do value Ron’s opinion.

Having said that, this book is a fascinating in-depth study of one particular work, one might even say a cross-dressed epic, and includes, as one would expect from Ron, both entertainment and enlightenment. Included is instruction on the different techniques required to conduct a rock band or a classical orchestra, information on converting decimal currency into old money, and the dangers inherent in overdoing the topping up of alcohol in one’s parents’ drinks cabinet with water …

There’s also some real information on the construction of a composition that we remain fond of, proud of, and in my case slightly bemused by. It was rather off my beaten track (opportunity for consideration and rejection of humorous word play here) and reminded me of my affection and gratitude for all those who assisted in this endeavour; in particular my friend and electronics guru, Mr Ron Geesin. I have to say that some issues are now so lost to my memory I can’t really make any judgements as to what we did right or wrong, or who failed to be suitably credited or rewarded.

Certainly if I have behaved in any way less than impeccably I will both apologise heartily, and rely on the statement that has served me well over the last forty years: ‘Roger Waters made me do it …’

Nick Mason

London, September 2012

INTRODUCTION

Let us get one hazy impression focussed into hard fact: this book lays out my experience in the composing and making of that twenty-three-minute work retrospectively named Atom Heart Mother on 16 July 1970. Before that, its basic formative structure had been performed live by Pink Floyd as The Amazing Pudding, subsequently modified and assembled from recorded sections to form the framework at EMI Abbey Road Studios for final issue on LP under the working title Untitled Epic. Since the final title, Atom Heart Mother, was also used to name the whole LP record, side two of which I had no part in, there has been further confusion as to what precise work various individuals have addressed their comments, not helped by vague and inaccurate reporting by members of the popular music press or the tangled netting of the World Wide Web. The qualifying word ‘suite’ was added later as partial attempt to distinguish The Work from The Album, but I am staying with the original title here.

Entirely from my point of view, this book is the story of a collaboration in the modern art medium of organised noise. Mixed metaphors abound. There are even some new words not found in any recognised English dictionary. I was never one for accepting what was taught. There is life after school. ‘What have we done?’ was certainly not understood at the time, got distorted through the rippled glass of several participants’ front doors and has now emerged out of the back door into the world’s garden – with no assistance from me, I can tell you, other than to make the score available to deserving enterprises.

I have winkled out every possible memory and used diaries, notepads and available factual documentation for substantiation. Recollections from Pink Floyd and its team were invited. I received none. You are conducted from our damp basement in Notting Hill, London, where drummer Nick Mason came to meet me, to my elevated padded cell in Ladbroke Grove where the dots were sweated on to paper. From there, you stagger into EMI Abbey Road Studios and very nearly stagger out again but for some chance reactions to traumas that found a way to get the job done. Questions arise, and some are answered. Eyebrows are frequently raised, to reveal a cheeky chap careering through doors of disorder into an understanding of life’s workings – maybe!

Pink Floyd has forever thrived on mystery, sometimes puffing at the smoke machine a bit too hard to shield what is essentially a very simple process, that of building a structure in sound and light for the amusement of others. ‘It’s all an illusion,’ is one of my crypticisms. I am no different: it’s just that my structures are more convoluted and tend towards the miniature as an art form.

The conclusion – and you will get it quite soon – is that this time-shifted collaboration would not be buried by any of Pink Floyd’s attempts but instead hovers above ground in its own mysterious vapour, held up by a magnetic field generated by the conflicts of aims and building materials that might have prematurely destroyed it. I call this process ‘playing with polarisation’. Forward, with all passion.

1

WHO AM I?

What an impertinent question, and one that might take a book to work out! As I swim, stride, shuffle and slide through this one, I am hopeful that you and I will come out with some idea.

I was born Ronald Frederick Geesin to Joyce (née Malcolm) and Kenneth Frederick Geesin in Kilwinning Maternity Hospital, Ayrshire, Scotland. My mother has told me that I was going to be called Roland, but there was another one in the road and, since two in one road would never do in polite middle-class Ayrshire, my parents swapped two letters round to get Ronald. So I was imbued with a healthy uncertainty at a very early age.

There were strands of creativity running through my ancestors: my mother’s grandfather, James Malcolm (1849–1909), was a good amateur scenic painter, and his brother, William Buchan Malcolm (1852–1917), was a fine early amateur photographer. The combination of these, together with my father’s technological involvement in constructional engineering, might have equipped me with some of the tools necessary for survival in this wire-wound and wounded machine age. I believe that all people are creative – it’s human nature – but some get provoked (they call it ‘driven’) into building extraordinary shrines, or little piles of stones by the roadside, to register their temporary tampering with space and time. Others then stand back to admire or fall over them.

Ron with mouth-organ c. 1957. Photographer: K.F. Geesin

Ron with first banjo 1959. Photographer: K.F. Geesin

I really do not believe in the many strained attempts to find direct hereditary connections to someone’s talent, typified by the question: ‘So who was the musical one in the family?’ We all love to find patterns in our lives that might reassure us that we are comfortably contained in some kind of identifiable framework, but the links are much less defined, possibly lying in a genetic trait to enquire, investigate, probe and venture alone, rather than to join a seemingly comfortable sheep pack that is herded around by ‘the system’.

So, I was born in Ayrshire and raised in Lanarkshire where my father built our bungalow overlooking a fairly featureless Clyde Valley. The one feature was a giant ‘bing’ (slagheap to you), a monumental by-product of the coal mine. My father’s roots were entirely English and my mother’s were English and Scottish, so that made me a quarter Scottish. This must have been why I never fitted in much socially and used to go on solitary bike rides up the more picturesque part of the Clyde Valley. Two aspects of life seem to have attracted me through my schooling years, unfairness and absurdity. In a music class, we were told things or played things from recordings. After a particularly pedestrian piece of Beethoven rendered from the gramophone I said, ‘Please sir, I didn’t like that!’ ’Geesin, you’re not here to tell me what you like, you’re here to learn!’ How unfair is that? My first instrument was the mouth-organ, more accurately the twelve-hole chromatic by Messrs. Hohner, following after that prodigy who never recovered, Larry Adler. How absurd is that?

As I became increasingly unruly in my awkward adolescent years through the late 1950s, my father introduced me to his business colleagues: ‘This is my scruffy son’. Maybe this was one of his attempts at second-hand dry Scottish humour, but it came out more like a desperate attempt to climb up above the middle of the middle class. Thirty years later I was moved to investigate our family history, principally along the Geesin line, and found that my father had been denying his origins. His great-grandfather died of cirrhosis of the liver, sometimes occupied as a night watchman in Gateshead, a town that was then a very scruffy underling of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland.

Negro Head, 1960.

Reinforcing my one-man revolution, I had also become attracted to Surrealism, actually a visual partner to the jazz medium. As an exorcism for excess energy, some work had to be done on a painting before sleep could be allowed. True to my way, even the method was improvised. All I had available were standard little cube pots of watercolours. If I wanted a thicker texture like that achieved with oils, I softened these with excess water and applied the creamed result with a shirt collar stiffener. Here I am, displaying that trait in artists that I criticise most: accenting the method as a possible cover up for weak content.

Ron with red petrol can and six-string banjo, 1964.

I never did find out what my father really thought about these pursuits. What he found out was that Hamilton Academy’s headmaster was despairing: ‘Take this boy away. We can do no more with him!’ Reacting to my paintings, my father thought: ‘Ah, an artistic bent! I might get him into an architect’s office.’ Less fortunately for me, his idea of such a house of design was one that served his world of steel construction. So I was installed at Wylie, Shanks and Partners, Glasgow, practising to roll my red and blue pencils to delineate some 3ft-wide gutter or other and forced to play cricket with a screwed-up ball of tracing paper and cardboard roll when the boss went out.