11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Gardeners who want to understand what is going on - or going wrong - in their gardens will find this book invaluable. It will also be a vital reference tool for all professionals, garden centres, nursery stock plant growers, landscape and amenity managers, and naturalists. The book employs a unique diagnostic approach to identifying and solving problems.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 275

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Gardeners who want to understand what is going on – or going wrong – in their gardens will find THE GARDENER’S BOOK OF PESTS AND DISEASES invaluable. It will also be a vital reference tool for all professionals, garden centres, nursery stock plant growers, landscape and amenity managers, and naturalists.

An introduction covers the principles of healthy gardens and how to recognise plant disease and interpret symptoms. Fox discusses various methods of control, both preventative and remedial. He then discusses how to differentiate between pests and diseases. The core of the book is an encyclopedic section which looks at individual problems under the headings ‘roots’, ‘bulbs, corms and tubers’, ‘leaves and buds’, ‘shoots and stems’,‘flowers’ and ‘fruits’. The final section shows how to maintain a garden free of diseases by the use of ‘integrated control’.

Dr Roland Fox is a lecturer in crop protection, Department of Horticulture, Reading University.

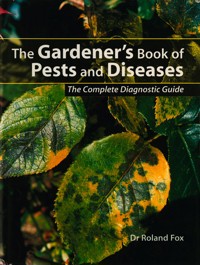

Jacket illustrations (front): black spot on rose leaves; (back, left to right): white blister on cabbage; leopard moth caterpillar exposed in apple twig; powdery mildew infection on Sweet William foliage; peach leaf curl; grey field slug on hosta leaf.

THE GARDENER’S BOOK OF PESTS AND DISEASES

Grey mould spotting on rose.

ROLAND FOX

THE GARDENER’S BOOK OF PESTS AND DISEASES

To Alicia,

who concentrates her efforts on growing her plants, despite all the pests and diseases in our garden, and a love of cats.

© Dr Roland Fox 1997

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

eISBN 9781849942225

Published in the United Kingdom as eBook in 2015 by

Batsford

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltd

Designed by DW Design Ltd, London

Photographs courtesy of Holt Studios International and East Malling Research Station (pg 63)

Contents

Introduction

Recognising plant diseases

Anticipating disease

What is disease?

The biology of plant pathogens

Bacteria are different

Recognising symptoms

Symptoms as evidence of disease

Use of macro-symptoms in disease detection

Use of symptoms for diagnosis

Drawbacks of depending on the use of symptoms for disease diagnosis

Symptoms caused by agents other than pathogens

Classification of major types of disease symptoms

Controlling plant diseases

Recognising damage by plant pests

Types of plant pests

Controlling plant pests

Recognising plant pests and diseases

i) Bulbs, corms and tubers

BACTERIAL ROTS – HYACINTH YELLOWS

BLUE MOULD

DRY ROT OF CORMS

EELWORMS

FUSARIUM BASAL ROT

MITES

NARCISSUS BULB FLY

TULIP FIRE

ii) Flowers

EARWIGS

GREY MOULD

PETAL BLIGHS - LILY DISEASE

BUDBLAST OF RHODODENDRONAND AZALEA

THRIPS

WEEVILS

iii) Leaves and buds

ADELGIDS

APHIDS

BEETLES

BIRDS

BLACK SPOT OF ROSES

CAPSIDS

CATERPILLARS

CRAB APPLE SCAB

FIREBLIGHT

FROGHOPPERS

GALL MIDGE FLIES

LEAFCURLS

LEAFHOPPERS

LEAFMINERS

LEAF SPOT

MAMMALS

MEALYBUGS, SUCKERS

MITES

POWDERY MILDEWS –

Apple powdery mildew

Rose powdery mildew

DOWNY MILDEWS –

Downy mildew of rose

Downy mildew of wallflower

RHODODENDRON GALL

RUSTS

Antirrhinum rust

Fuchsia rust

Mahonia rust

Pelargonium rust

Periwinkle rust

Mallow and hollyhock rust

Rhododendron rust

Rose rust

SAWFLIES

SCALE INSECTS

SLUGS

SNAILS

SOOTY MOULDS

SYMPHILIDS

THRIPS, BUGS

VIRUSES

WEEVILS

WHITE BLISTER

WHITE FLIES

WOODLICE

iv) Roots

CHAFER BEETLE

CRICKETS

COCKROACHES

CUTWORMS

DAMPING-OFF

HONEY FUNGUS ROOT ROT

LEATHERJACKETS

MILLEPEDES

PHYTOPHTHORAROOT ROT

ROOT APHIDS

ROOT FLIES

ROOT MEALYBUGS

ROSELLINIA WHITE ROOT ROT

SCIARIDS

SCLEROTINIA DISEASES

STOOL MINERS

SPRINGTAILS

SWIFT MOTH CATERPILLARS

SYMPHYLIDS

VINE WEEVILS

WIRESTEMS

WIREWORMS

v) Seeds and fruits

ANTS

BEETLES

BIRDS

BROWN ROT

CATERPILLARS

MAMMALS

vi) Shoots and stems

APHIDS

WOOLLY APHIDS

BEETLES

BUTT OR FOOT ROT OF PINE

CANKER

CAPSIDS

CATERPILLARS

CROWN GALLS

DUTCH ELM DISEASE

MAMMALS

SAWFLIES

SCALE INSECTS

WASPS

WITCHES BROOMS

Comprehensive cross index of plants, diseases and pathogens

Bud Blast on bud.

Introduction

Ensuring a healthy start by creating a healthy garden

Gardens can be designed to exclude disease and pests from the onset. If this task is shirked the penalty is severe. Perpetual watchfulness will then be needed to counter the plagues of hungry pests and a variety of epidemics of withering disease.

Gardens are highly complex artificial environments that have been designed by humans. While all plants eventually fade, wither and decay in time, every keen gardener attempts to delay the process of decay as long as possible. In gardening, as in other spheres, success often relies on a combination of luck and good judgement to ward off the ravages of time and nature. Apparent miracles are possible. We all know of gardens that appear in good health and others where nothing grows well except the bill for new plants which never thrive. Just like an athlete, it pays to start good practices right from the beginning. Apart from disease organisms and pests that blow in from time to time, the health of a garden is determined when the soil is prepared for the first seeds that are sown, and the first trees or shrubs that are planted. The consequences last until remedial action has to be taken; in the meantime poor crops will be harvested and the garden will not flourish.

Sensible planning is essential in order to grow plants to their maximum potential, which will remain beautiful and healthy. Most pests and diseases reduce quality, some may occasionally cause the complete destruction of certain plants if detected too late. In these circumstances it is essential to detect outbreaks at the earliest stage and start preparing control measures immediately infection by disease or infestation by pests has been seen in neighbouring gardens or if damage is anticipated.

The extent of the injury that is likely to result to a plant from infestation by an unidentified pest or disease cannot be reliably forecast until it has been accurately diagnosed.

Although keys can be used, most gardeners may prefer to study the illustrations of the pests and diseases of major garden plants. Examples of the most damaging pests and diseases of key garden plants are illustrated in the encyclopaedic section of this book.

If a particularly destructive or unusual pest or disease is suspected, the causal agent must be quickly and accurately identified, so that appropriate action can be taken. Some diseased plants may even have to be eradicated under a Plant Health Order; many of these are indicated in the illustrations. More often an appropriate control measure has to be selected quickly if damage is to be minimised.

Close up of unidentified ‘target’ like fungal leaf spot on begonia leaf.

Recognising plant diseases

The principles of plant pathology

Anticipating disease

Nearly all outbreaks of disease result from one or more of four major sources of infection, regardless of whether the pathogen is a fungus, virus or bacterium: (1) seed, (2) other planting material (seedlings, bulbs, corms, cuttings grafts etc), (3) airborne disease pathogens, (4) soil-borne disease pathogens. Seed that is available commercially must be tested to ascertain that it is free of pathogen contamination. Although heavily infected seeds can reveal direct evidence of pathogens such as bits of fungi or gummy masses of bacteria, most seeds rarely show any clear symptom of disease. In the average garden, the extent of many soil-borne diseases only becomes apparent over a number of seasons as they are rather slow-growing. Often this historic perspective is lacking and a range of diagnostic techniques (covered in Fox, 1993) is necessary to detect their presence in the soil before planting.

Once the amount of soil-borne disease is known, airborne pathogens form the main threat. If the arrival of showers of spores onto plants is correctly anticipated, protectant sprays and other control measures can be synchronised with them for best control. Several fungi as well as bacteria hitch a ride on a wide range of insects that feed on plants or their nectar. Some other fungal as well as bacterial pathogens, and many viruses arrive within airborne insects and mite vectors that can be controlled by insecticides or acaricide sprays.

Detecting early stages of disease before it can cause too much damage

Ever since the middle of the 19th century, scientists have paid considerable attention to discovering the entire details of the life cycle of the organisms that cause disease. As a consequence, it has been possible for plant pathologists to predict severe levels of diseases from past outbreaks. Latent infection is now recognised to be common among many diseases which become apparent after harvest, such as soft rot (Erwinia carotovora) and gangrene (poma exigua var. foveata) on potatoes, neck rot of onion (Botrytis allii) and grey mould of strawberries (Botrytis cinerea). As a result of this knowledge, recommendations for treatment for many of these diseases have been improved by enabling the application to be carefully targeted at a particular growth stage of the plant but only if a gardener is observant and well trained enough to recognise the presence of the pathogen.

What is disease?

Frequently a plant may not grow as well or as quickly as we would hope, or it may even die, because it is not functioning properly. This malfunctioning can be caused by a great variety of causes. Many insects or their larvae bite and burrow into leaves, stems and fruits. Water or minerals may be lacking or present in excess. The plant could be a casualty of pesticides or pollution or even be struck by lightning!

Strictly speaking, a plant only has a ‘disease’ whenever its malfunction is caused by a virus, a fungus or a bacterium. Other malfunctioning should be considered as a disorder. An expert in plant disease, known as a plant pathologist, combines the skills of your general practitioner as well as a public health official. In essence, a plant pathologist is a plant doctor. The diseases in the main section of this book have been categorised as per the principal part of the plant that is affected, such as leaves, fruits, roots, etc. However, you can sometimes find similar symptoms on several different parts of a plant. In each of these sections the English name of the disease is listed alphabetically and there is a very comprehensive cross index based on the plant, its Latin name, common name of the disease and the Latin name of the pathogen. Sometimes the same or a similar type of causal organism can have similar effects on a number of different host plants and may also require similar treatment.

The biology of plant pathogens

In order to understand why your plants become diseased we will briefly consider some features of the general biology of fungi, bacteria and viruses as pathogens. First, none of these organisms are themselves plants. Virtually all real plants contain chlorophyll which enables them to synthesise the organic nutrients required for energy and growth from sunlight, carbon dioxide in the air and water absorbed from the soil. Although some older textbooks link fungi to the plant kingdom, most fungi are now considered to be more closely related to animals and do not usually cause disease. Instead, they digest dead organic matter through which they grow by secreting enzymes and then absorbing the resulting substances. Man has learned to consume many of these fermented products – like the oriental tofu, blue cheeses, soy sauce, beers, wines and cider – but to shun those fruits and vegetables contaminated by moulds and rots.

Many fungi are edible and are grown commercially on compost or collected from the wild. Some of the latter, like ceps, chanterelles and truffles, grow in association with green plants as mycorrhiza but many woodland fungi decay leaf litter and fallen wood as saprophytes (organisms living on dead matter of all sorts). Some specialised fungi live on airplane fuel, and similar unusual sources of carbon compounds and other essential elements. Although they include hundreds of species that are important in causing garden diseases, a relatively small percent of all fungi attack plants. Certain pathogens are able to live on either dead or living matter (facultative pathogens). Some of these facultative pathogens can live on dead and dying organic matter, then use this as a base from which to attack healthy plant material. Even fewer fungi are actually completely (or very nearly totally) dependent on living plants as parasites; these are known as obligate pathogens. However, many obligate pathogens, such as the rusts and powdery mildews, are extremely common and damaging. In fact the organisms generally thought of as fungi are actually members of several distinct kingdoms of their own! Of these, only one resembles the plant kingdom by having a cell wall comprised of cellulose. However, like many animals, including man, these fungi – known as the Oomycetes – reproduce sexually through the fusion of motile cells that in some ways resemble sperm.

There are many hundreds of thousands of fungal species. Most, but not all, fungi consist not of single cells like so many plants and animals, but of microscopic tubular threads termed hyphae which are collectively known as a mycelium. Hyphae germinate from a variety of spores formed by sexual or asexual reproduction. Many varied fungi forms produce several different spores of distinctive types. These are formed by various characteristic processes.

These spores develop into either the well-known toadstools or numerous other smaller but equally intricate fungal constructions. Mycelium of many plant pathogens spreads out through the soil, decaying vegetation and plants. You may see it as a white cottony material. Many fungicidal chemicals work by controlling spore germination, but others can control the hyphae within plants. The former are called protectants, whereas the latter are systemic eradicants (these eradicants are said to possess ‘kickback’ action).

Generally the asexual state of the fungus causes the disease. This is given a different name to the usually less common sexual stage. Recognition of the particular type of spore that is produced is vital in traditional fungal taxonomy. Some fungi, the Deuteromycotina, sometimes called the fungi imperfecti, produce only asexual spores called conidia. However, if such fungi are later found to undergo sexual reproduction to make ascospores in sac-like structures; they are then transferred to the Ascomycotina. The majority of fungi belong to this class. Fungi in the class Basidiomycotina – like mushrooms or toadstools, rusts and smuts – produce exposed sexual spores termed basidiospores. Other spores are produced in the rusts and other fungi.

Mealybug colony on houseplant.

Pseudofungi include the Oomycetes, such as the causal agents of potato blight, downy mildews and damping-off, and similar organisms such as those responsible for potato wart have free-swimming zoospores which move through films of water both in the soil and across the surface of plants. Clubroot, although caused by a taxonomically distinct organism, also produces zoospores.

Fungi persist under adverse conditions as mycelium or as especially resistant spores or other impenetrable structures such as tough masses of mycelium (sclerotia). Once these are controlled the life cycle of the pathogen is destroyed.

Bacteria are different

Very few plant pathogenic bacteria produce spores. Actinomycetes like Streptomyces scabies that causes common scab form powdery spores from the tips of their chains of vegetative cells. Most bacteria exist as individual minute single rods or round cells that multiply by simple binary fission, as the cells split into two with remarkable speed, especially under tropical temperatures. Many bacteria are capable of movement through fluids. The conspicuous symptoms and other effects of bacterial infections often resemble those produced by fungi. The presence of bacterial pathogens is often difficult to corroborate as bacteria can be found virtually anywhere as saprophytes.

Bacterial diseases often prove difficult to control once they are established. Fungicides are seldom effective against bacteria.

A number of extremely important bacterial diseases regularly occur in gardens in Britain. Fireblight caused by Erwinia amylovora is one of the most serious diseases that can be found on cotoneaster, pyracantha, Sorbus, apples, pears and many other pomaceous plants. Soft rot of vegetables and some fruits is caused by another related bacterium, Erwinia carotovora. The damage that this causes is likely to be all too familiar to your sense of smell! Other bacteria, often from the tropics, are very important as pathogens on many glasshouse plants.

Recognising symptoms

It is essential that a plant disease has been correctly identified before any control is attempted, as some treatments designed to destroy one pathogen may encourage others. However, while the signs or symptoms of some common pathogens are familiar and may be trusted, those of many others frequently prove less reliable as a guide to the identity of the pathogen. Nevertheless, when clearly distinct, symptoms can often help to monitor the spread and prevalence of diseases on a range of garden plants.

Symptoms as evidence of disease

Most symptoms are the visible outward signs of a distinct malfunctioning in a host plant brought about by the action of harmful pathogens or other causal agents such as mineral deficiency or pollution. Symptoms can range from extremely slight to very serious, chronic to acute. They may be localised, resulting in restricted injuries like leaf spots. Some are systemic, spreading throughout an affected plant to cause widespread symptoms such as distortion or rot.

Obligate fungal pathogens depend on haustoria, which are specialised hyphae that drain nutrients from host cells without killing the plant. This is a successful strategy as the host survives virtually intact. If the attack were to be too extensive the host might be killed, followed either by the death by starvation of the obligate pathogen or the hasty formation of resistant spores.

Facultative pathogens are usually considerably more injurious. At first they grow amongst host cells, but often later they penetrate within, so as the lesion advances it causes substantial damage at the cellular level. This results from a series of reactions between two components, the basic host cell functions (photosynthesis, respiration and transport) and activities of the pathogen (toxins, enzymes and growth regulators). Although a conspicuous symptom is a clear confirmation of a detrimental interaction, many symptoms are not readily discernible since they occur at the cellular level.

However, as soon as these micro-symptoms occur en masse, a macrosymptom may result. This is clearly visible to the naked eye. Although the onset of perceptible changes in host function – or morphology – may ultimately become evident by the development of a particular micro- or macro-symptom of the condition of the disease, sometimes the most obvious symptom of a plant disease consists of the vegetative or fruiting structures of the pathogen itself, often termed ‘signs’. Other manifestations of disease require a sense of smell, taste or touch.

Use of macro-symptoms in disease detection

Inspecting plants for macro-symptoms may be relatively rapid. However, the appearance of any symptom represents a relatively late stage in the process of infection and colonisation by a pathogen. Yet the unexpected appearance of a symptom is usually sufficiently conspicuous to worry a keen gardener into identifying the causal agent.

Use of symptoms for diagnosis

Experienced gardeners can sometimes accurately diagnose a common disease from its symptoms even when seen from a fast car. However, in most cases a rather more detailed examination is required as plants are covered by many micro-organisms that are unable to attack plants.

Drawbacks of depending on the use of symptoms for disease diagnosis

A symptom can be so distinctive that it confers the common name of the disease. Often several pathogens cause similar symptoms. Symptoms range in severity; some are extremely destructive, others hardly seem worth treating, but even slight damage become important if persistent. The loss of a single leaf is trivial, but when all the leaves are lost the plant can die. If a pathogen rots the roots of a plant, permanent wilting may follow. Similar symptoms result from any blockage to the vascular system, for example, when filled by a wilt disease. Alternatively its leaves could have been severely damaged by a foliar pathogen.

Symptoms caused by agents other than pathogens

From the outset it is essential to make sure that the symptom is due to a pathogen and not caused by an insect, nematode, a variety of other pests, parasitic plants, some weeds, microbial toxins or a range of soil or climatic conditions. Symptoms that look very much like many diseases may be produced by excessive imbalances in minerals, exceptionally high or low temperatures, light, water supplies, chemicals, lightning and wind. Non-infectious disorders are therefore often mistaken for diseases induced by pathogenic fungi, bacteria and viruses. Both affect the plant in similar ways. Now and then disorders allow pathogens to invade and injure the plant. This hinders diagnosis. Damage differs with different plants, their maturity, the season and the different parts of the plant. Many garden plants can survive very low temperatures and frost, yet freezing may injure or kill twigs and branches and even split trunks after heavy frost. Fruit crops may be lost when flowers are killed in late frosts and some plants, such as dahlia, can even be killed by early frosts before flowering. In cases of sunscald, fruit or foliage is injured by bright sunshine. Heat cankers of the collar and black heart of potato are caused by temperatures at which the rate of respiration of oxygen is so high that it is used up too fast to be replenished. Poor light causes etiolation, but an excess may induce sunscald of bean pods. Drought is often a problem. Maize starts to roll its leaves if short of water; if the drought continues its top dries up so that grain cannot form. Trees may die in prolonged droughts. Most garden plants thrive on relatively well-drained soil, but cannot survive persistent floods that suffocate the root system, allowing micro-organisms to invade.

Grey mould disease on paeony flower buds.

A number of apple varieties suffer badly from scald, a serious physiological disorder incited by the gases that they emit in storage. Yellowing and other colour changes in various patterns in the leaves, marginal scorching and other forms of necrosis, as well as stunting or deformation of the fruit may indicate that one or more of the elements in the soil essential for plant growth is deficient or has combined with other soil elements making them unavailable to the plant. More rarely there is an overabundance of salts in excessively acid or alkaline soils.

Symptoms of disease are conspicuous when some of the major fertilizer elements such as potassium, phosphorus or nitrogen are lacking. Damage is most often marked when some of the minor elements such as boron, zinc and manganese are missing in the soil or are rendered unavailable. An overabundance of some nutrient elements, such as boron, in irrigation water or as a contaminant in potash fertilizers, results in a marginal necrosis of the older leaves. Occasionally mineral excess causes stunting, resulting in serious losses and even dead plants. It is often difficult in practice to distinguish clearly between the symptoms of disorders that are due to a deficiency and those due to an excess. Apparent shortages of one element are often caused by a surplus of another element that interferes with the solubility, absorption or function of others.

Pesticide sprays may sometimes cause phytotoxic blemishes on the fruit or foliage. The most common injury is a dull brown spotting of the leaves or burning of margins and tips. Even minute amounts of the growth regulator herbicides can deform or kill certain plants like tomatoes. Other consequences of drift of spray droplets include poor growth, excessive drought injury and premature flower or fruit drop.

Classification of major types of disease symptoms

Pathogens can cause a variety of immediate or delayed injuries to plant functions following infection. These plant functions (together with the groups of diseases affecting them) include the mobilisation of stored food (damping-off and seedling blights), absorption of water and minerals (root and foot rots), water transport (vascular wilts), meristematic activity (leaf curl, witches’ broom, club-root, galls), photosynthesis (leaf spot, anthracnose, blight, mildew, rusts, leaf smuts, viruses), translocation (some diseases caused by viruses, viroids, mycoplasmas, rickettsias), storage (postharvest diseases of fruits, perennating and storage organs) and reproduction (head smuts and ergot). Various symptom types may be grouped together on the basis of these distinct underlying mechanisms. Diseases usually have several symptoms which together constitute a syndrome, some of which are so distinctive that a disease can be readily identified and controlled.

Controlling plant diseases

The effective control of plant diseases can be ensured in several different ways. Many of these methods do not require the use of chemicals even though this is often the usual procedure adopted by amateurs. Only a few of the fungicides that are available to professional growers can be used in the garden. Some of these products are systemic and can be applied either to the roots or leaves to eradicate diseases that have already become established in younger parts of the plant. Unfortunately, although such fungicides are extremely effective initially, prolonged use in the absence of other treatments can select strains of some pathogens that are resistant to the systemic fungicide. The other fungicides that are available are protectant and must be applied to plants before infection takes place in order to establish a protectant barrier between the host and the causal agent of disease. It is much less common for resistant strains to develop into most standard protectant fungicides. Most fungicides available amateurs to use only control foliar diseases adequately. Nonetheless, it is also possible for an amateur to purchase seeds which have already been treated with small amounts of a systemic or protectant fungicide by the seed company. This fungicide is intended to control any seed-borne pathogens and in addition give some protection against soil-borne diseases such as damping-off. Most garden fungicides are wettable powders which consist of finely ground or precipitated particles that remain in suspension in the water used to spray them but do not dissolve. In addition to between 25 and 50 percent of the active ingredient, wettable powders also contain a wetting agent, a thickening agent, a clay and a suspension agent. Most fungicides applied in the garden are sprayed through the nozzle of a simple hydraulic aerosol sprayer of some kind, whereas commercial growers use a much wider variety of equipment. Many gardeners are not keen to use fungicides for various reasons including the fear that they might harm the environment, the dislike of handling pesticides themselves, the cost of purchasing spray equipment and the desire to use more traditional techniques. Fortunately there are a number of effective methods of disease control that do not rely on the use of chemicals at all, as well as others that integrate their use into systems that reduce reliance on them. Integrated disease management is at present largely used by professional growers, but elements of this philosophy can be adopted in the garden. These systems are based on the idea of containing damage or loss below certain economic levels. This aim is achieved by the management of the growth of plants by several processes in which disease is only one component. As a result there is less dependence on chemicals and hence a reduction of possible detrimental effects on non-target, and possibly beneficial, organisms. There are more of these techniques available than is generally realised by amateur gardeners.

One of the most important lessons that any gardener can learn is not to introduce diseases into the garden. It is very easy to purchase diseased plants from charity plant sales or receive them from well-meaning friends and neighbours. Among the diseases spread in this way are a number of serious, soil-borne pathogens including honey fungus root rot of trees, which has been disseminated in this way on a number of occasions to new gardens and has then been very difficult to eliminate. On a larger scale so many diseases have been transmitted between countries in the same way that international legislation by regional plant protection organisations of the Food and Agriculture Organisation has been set up to prevent the accidental spread of diseases such as downy and powdery mildew of grapes and powdery mildew of gooseberries – which were introduced into Europe from North America – and Dutch elm disease, apple canker and black leg of crucifers which spread in the opposite direction. In addition to the international spread of diseases, some of which were possibly imported by keen gardeners who disobeyed quarantine laws in Britain, some serious diseases such as potato wart are localised and there is legislation to prevent further spread. There has also been similar legislation, albeit ultimately unsuccessful, against the spread of Dutch elm disease, fireblight and white rust of chrysanthemums. Also, it is illegal to offer for sale plants affected by gooseberry powdery mildew, onion smut, cabbage club root, red core of strawberry, progressive wilt of hops or even the pear variety ‘Laxton Superb’ which is known to be especially susceptible to fireblight. The important message here is to make sure that you only add healthy plants to your garden and avoid the temptation to bring in any plant that is not in the best condition. This would therefore rule out the introduction of many wild plants. It is most important to obey plant health rules, however strict they appear to be, as once a disease is introduced it is very costly to eradicate it – if this can be done at all. Only a few cases of the successful eradication of a plant disease have been reported; the most effective was the complete elimination of citrus canker from florida and the Gulf of Mexico, and that was at the cost of 20 million trees.

Eradication of diseases from the soil, seeds, vegetative parts or nonliving surfaces is an effective way of cleaning up plants and their environment. In many cases chemicals are used, but eradication by physical means such as heat is also widely used. Heat can be applied in the form of thermal radiation from a heating element, fire used to burn garden debris, radiation from the sun, ionizing radiations or microwaves, live or pressurised steam, or hot water. The use of heat is generally limited to small areas such as greenhouses, nurseries and small transplant seedbeds, but is rarely used by amateur gardeners. Professional seed and bulb producers have used heat, particularly hot water, to disinfect seeds, bulbs and corms, but the gap between success and damage is often too small for this technique to be worthwhile. Even though it is quick to use and usually leaves no harmful residues, heat is not easy to handle and destroys organic matter in the soil, and burning causes air pollution. Another adverse factor is that soil which has been heat-sterilized is easily reinfected by soil-borne pathogens. It is very difficult to sterilize soil or compost completely. Often soil or compost has actually been pasteurized, that is, it has been heated to 62°C. This kills the more sensitive organisms such as most plant pathogenic nematodes, many bacteria and fungi such as Pythium. Moist heat is more efficient than dry heat in eliminating pathogens as water conducts heat more readily than air. Steam readily denatures the proteins and membranes in micro-organisms for fewer heat units than dry heat. In hot countries it is common for patches of soil to be disinfected by heat from the sun; now a development of this technique involves the use of a polythene sheet to heat the soil to as much as 55°C to a depth of 5cm. This technique is known as solarization, but it will probably remain restricted to tropical and Mediterranean areas. Kitchen microwave ovens have been regularly used to disinfect small batches of soil and composts, but this method is not always successful because the uneven texture of some soils prevents complete pasteurization.