Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

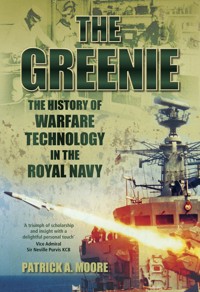

In the Royal Navy vernacular, the term 'greenie' describes the officers and ratings responsible for the electrical engineering functions of the fleet. Electrical engineering has 'driven' the Royal Navy for far longer than one might imagine, from solving the problem of magnetic interference with the compass by the ironclad early in the 20th century onward. Author Commander Moore traces the development of technology from 1850 to today's integrated micro computers that control almost every aspect of navigation, intel, and strike capacity. At the same time, he describes how the Navy's structure and manpower changed to accommodate the new technologies, changes often accelerated in wartime, particularly in World War II. Without the full cooperation of naval establishments and organisations and various public and private museums and manufacturers, this work would have been impossible to produce. Written in an anecdotal, narrative style but with a complete mastery of the science itself, it will appeal not only to those interested in the history of the Royal Navy but also those many thousands, past and present, who can claim the honour of calling themselves one of the Greenies.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 635

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE GREENIE

THE GREENIE

THE HISTORY OF WARFARE TECHNOLOGY IN THE ROYAL NAVY

PATRICK A. MOORE

The Greenie is dedicated to those members of the Electrical Branch, its predecessors and successors, who gave their lives in the service of their country and whose memory was poignantly refreshed by the countless references to them and their extraordinary deeds encountered during the research for this book.

Except where otherwise attributed, all observations and opinions expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views of any other person or organisation, including the Government, Ministry of Defence and the Royal Navy.

Many images used to illustrate this book have been taken from donations made by individuals of historical material and memorabilia to various archives and museums, much of which remains uncatalogued with copyright and ownership untraceable, and it is hoped that by making such donations that the donor has consented to the reproduction of the material as seen fit by the museum concerned. The publishers will be happy to provide accreditation on reprint and apologise for any omissions.

Where images used contain material which is from official or semi-official documentation or has Royal Navy subject matter content, these images have been reproduced with the agreement of the Ministry of Defence without prejudice to the actual ownership of the copyright.

All royalties accrued for this title will be donated to Royal Navy charities under the auspices of the Collingwood Officers Association and the Royal Navy and Royal Marines Charities.

First published 2011 by

Spellmount, an imprint of

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2016

All rights reserved

© Patrick A. Moore, 2011

The right of Patrick A. Moore to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8013 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1 Early History

Chapter 2 Electrical Technology 1850–1938

Chapter 3 Managing the Technology 800–1938

Chapter 4 Wartime Developments 1939–1945

Chapter 5 Electrical Engineering Manpower 1939–1945

Chapter 6 Time for Change

Chapter 7 The Middleton Report

Chapter 8 The Electrical Branch

Chapter 9 Entering the Computer Age 1946–1966

Chapter 10 The Weapons and Radio Branch

Chapter 11 The Integrated Combat System 1967–1978

Chapter 12 The Weapons and Electrical Engineering Branch

Chapter 13 The Weapons Engineering Sub Branch

Chapter 14 The Advent of the Micro-Computer 1979–1990

Chapter 15 Warfare Branch Development

Epilogue

Appendix 1 Greenie People

Appendix 2 Greenies in Action

Appendix 3 Greenie Recollections

Appendix 4 Contributors

Appendix 5 Wartime Electrical Training Establishments

Bibliography

End Notes

ABBREVIATIONS

AB

Able Seaman

AB(EW)

Able Seaman (Electronic Warfare)

AB(M)

Able Seaman (Missile)

AB(R)

Able Seaman (Radar)

AB(S)

Able Seaman (Sonar)

AD

Action Data

ADA

Action Data Automation

ADAWS

Action Data Automated Weapons System

ADC

Action Data Communications

AE Branch

Air Engineering Branch

AFCT

Admiralty Fire Control Table

AFO

Admiralty Fleet Order

AIO

Action Information Organisation

AM

Amplitude Modulation

ARM

Availability, Reliability and Maintainability

ASW

Anti-submarine Warfare

AWT

Air Warfare Tactical

AWW

Air Warfare Weapons

BRNC

Britannia Royal Naval College

CACS

Computer Assisted Command System

CA(W)

Control Artificer (Weapons)

CCWEA

Charge Chief Weapons Engineering Artificer

CEA

Control, Electrical Artificer

CEM

Control Electrical Mechanic

CEW

Communications and Electronic Warfare

CDS

Comprehensive Display System

CINO

Chief Inspector Naval Ordnance

CIWS

Close In Weapons System

CNEO

Chief Naval Engineer Officer

COTS

Commercial Off The Shelf

CPOET

Chief Petty Officer Engineering Technician

DCI(RN)

Defence Council Instruction (Royal Navy)

DAMR

Department of Air Maintenance and Repair

DASW

Department of Anti-Submarine Warfare

DEE

Department of Electrical Engineering

DF

Direction Finding

DFCT

Dreyer Fire Control Table

DNAR

Department of Naval Air Radio

DNC

Directorate of Naval Construction

DNO

Director of Naval Ordnance

DNOA(E)

Director of Naval Officers Appointments (Engineering)

DRE

Department of Radio Equipment

DTM

Department of Torpedoes and Mines

EA

Electrical Artificer

EBD

Engineering Branch Development

EBWG

Engineering Branch Working Group

ECCM

Electronic Counter-Counter Measures

ECM

Electronic Counter Measures

EED

Department of Electrical Engineering

EM

Electrical Mechanic, or Electrician’s Mate 1946–1955

ERA

Engine Room Artificer

ESM

Electronic Support Measures

ESO

Explosives Safety Officer

ET

Engineering Technician

EW

Electronic Warfare

FM

Frequency Modulation

GWS

Guided Weapons System

HACS

High Angle Control System

HF

High Frequency

IFF

Identification Friend or Foe

LEM

Leading Electrical Mechanic

LET

Leading Engineering Technician

LFLow Frequency

LOM

Leading Operator Mechanic

LTO

Leading Torpedo Operator

LTO(LP)

Leading Torpedo Operator(Low Power)

MAD

Magnetic Anomaly Detection

ME Branch

Marine Engineering Branch

MEA(L)

Marine Engineering Artificer (Electrical)

MF

Medium Frequency

MEM(L)

Marine Engineering Mechanic (Electrical)

MEM(M)

Marine Engineering Mechanic (Mechanical)

MEO

Marine Engineering Officer

NDA

Naval Discipline Act

NLD

Naval Electrical Department

OA

Ordnance Artificer

OC

Ordnance Control

OEA

Ordnance Electrical Artificer

OEM

Ordnance Electrical Mechanic

OIC

Officer in Charge

OM(AW)

Operator Mechanic (Air Warfare)

OM(C)

Operator Mechanic (Communications)

OM(EW)

Operator Mechanic (Electronic Warfare)

OM(MW)

Operator Mechanic (Mine Warfare)

OM(UW)

Operator Mechanic (Underwater Warfare)

PEC

Printed Electronic Card

POET

Petty Officer Engineering Technician

PPI

Plan Position Indicator

PWO

Principal Warfare Officer

QO

Quarters Officer

Radar

Radio Detection and Ranging

RCM

Radar Counter Measures

RDF

Radio Direction Finding

REA

Radio Electrical Artificer

REM

Radio Electrical Mechanic

REME

Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

RIS

Radio (or Radar) Interference Suppression

RNVR

Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve

Rx

Receiver

SCOT

Satellite Communications Operating Terminal

SD

Special Duties

SHF

Super High Frequency

SQ

Specialist Qualification

TAS

Torpedo and Anti-submarine

TBS

Talk Between ships

TGM

Torpedo Gunner’s Mate

TM

Torpedo Mechanical

TS

Transmitting Station

Tx

Transmitter

UHF

Ultra High Frequency

VFO

Variable Frequency Oscillator

VHF

Very High Frequency

VST

Vent Sealing Tube

VT

Velocity Trigger or later Variable Time

WBD

Warfare Branch Development

WD

Weapons Data

WDO

Weapons Data and Ordnance

WEA

Weapons Engineering Artificer

WE Sub Branch

Weapons Engineering Sub Branch

WEE Branch

Weapons and Electrical Engineering Branch

WEM(O)

Weapons Engineering Mechanic (Ordnance)

WEM(C)

Weapons Engineering Mechanic (Control)

WEM(R)

Weapons Engineering Mechanic (Radio)

WEO

Weapons Engineering Officer

WRE Branch

Weapons and Radio Engineering Branch

WRNS

Women’s Royal Naval Service

WT

Wireless Telegraphy

WTEE

Wireless Telegraphy Experimental Establishment

WM

Weapon Mechanician

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The idea of documenting the story of the Electrical Branch arose during the run up to the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Branch in 1996, and it became known as ‘The Greenie Project’. The Editor of the Review of Naval Engineering magazine, at the time Lieutenant Commander Rod Chadwick, started the research work by using the magazine archives, going back to the 1940s, to document the early background of the Branch. Rod was assisted in his work by a team which comprised Lieutenant Pat Hunt, Lieutenant Mandy Clarke, Lieutenant Stewart Heather and Radio Supervisor Chris Rickard. This team extended the research using the Ministry of Defence archives in London and gathered anecdotal contributions, through interviews and letters, from many original members of the Electrical Branch and their successors. The resulting collection of material was incorporated into a first document that, regrettably, during the transformation of HMS Collingwood from a Weapon Engineering to a Maritime Warfare Establishment during the early 2000s, started to gather dust on a shelf. As the tide of change subsided, so the early work was brought to the attention of the committee of the Collingwood Officers’ Association and they decided to back completion of the project. In 2007, the committee persuaded me to take on the task of writing and editing The Greenie and agreed that I should write the book such that it would be of interest not only to anyone who may have wielded a ‘wee megger’ in the Royal Navy but also the many civilians with association through either the Ministry of Defence or the defence industry.

During the book’s development I felt obliged to reassess its scope as more information came to light on the earlier roots of electrical engineering in the Royal Navy and I discovered more about the close links between Branch restructuring and the major changes in naval warfare technology going back well into the nineteenth century. This further information, and the illustrative material used to eventually bring it to life, could not have been obtained without the help of the many organisations, both commercial and volunteer, that still exist in order to ensure the retention of the Royal Navy’s engineering heritage. I would like to thank those organisations and the individuals who provided so much help in mining their respective archives for data and for supplying me with so many interesting images and giving me access to many documents which have remained undisclosed for well over 100 years. Those involved include the Naval Museum, Portsmouth (Stephen Courtney, Graham Muir), Naval Museum, Devonport (Jerry Rendle), Naval Historical Branch, Portsmouth (Jenny Wraight, Iain MacKenzie), BRNC Museum, Dartmouth (Richard Porter), Museum of Naval Firepower, Gosport (Derek Gurney), The Museum, HMS Excellent (Lieutenant Commander Brian Witts), HMS Collingwood (Commander Tim Stoneman, Keith Woodland), BAE Systems (Phil Stanton, Alison Gasser) and finally the Collingwood Radar and Communications Museum (Lieutenant Commander Bill Legg) where the full resources of the museum were made available for my use. In addition to the above sources, I used many others to correlate and contribute information in order to develop a coherent historical picture of what is an extensive subject. To all of the people who were so generous with their time and the authors of the many publications consulted and listed in the bibliography, I would like to extend my sincerest thanks. With those thanks comes a recommendation to anyone who finds The Greenie of interest to follow up with the organisations and books listed for a more in-depth coverage of the many subject areas covered in this book.

A special acknowledgement is due to the memory of ‘JH’ (Jack Hughes), ‘Tugg’, ‘Sessions’ and ‘Dink’, whose iconic cartoons for many years have lightened the reading of Live Wire, Naval Electrical Review and the Admiralty Signals Establishment Bulletin, all informal magazines used to communicate newsworthy engineering-related topics and feedback to and from the Fleet. My thanks to HMS Collingwood and the Collingwood Museum for allowing me the pleasure of resurrecting some of their work from these magazines. While the full publishing heritage of the works by these four cartoonists has proved to be elusive, it is hoped that use of their work to add colour and character to the story of The Greenie will be recognised as the tribute intended.

On a more general note, the writing of this book was made even more interesting by contributions from the many who thought that the history of the ‘Greenie’ was something worth recording. With an upfront apology for any transcription errors and editorial licence that may have been exercised on their original efforts made some time ago, I would like to thank all of those people whose personal memories of the Branch are chronicled in these pages. Unfortunately, space limitations have prevented the inclusion of all contributions passed to the original research team by ‘Greenie’ enthusiasts. For those contributions, I would like to express my grateful thanks and to apologise for the omission of anything that may have had special significance for the donor.

For their support in the actual production of The Greenie, I would like to record my thanks to David Riley for his restoration work on some of the early images and Lieutenant Commander (S) Richard Hart, and Lieutenant Commander (E)(WE) John Stafferton for their help in the proofreading of the text and constructive criticism of the content. Also, John’s assistance with the daunting task of providing a comprehensive index, an essential element of a book such as this, was most welcome and certainly helped to lighten the editing load.

Finally, I would like to give thanks to the late Vice Admiral Sir Philip Watson KBE LVO CEng FIET CBIM for agreeing to preview my proofing version of The Greenie and the generous words he contributed to the Foreword. One of the most distinguished Greenies, Admiral Watson was a founder member of the Electrical Branch and he later became Director General Weapons and Chief Naval Engineering Officer. Prior to reaching those pinnacles of achievement for an electrical officer, he was also my Captain when I was appointed to Collingwood for Application Training in 1969. He might possibly have remembered this as we did spend every Monday morning for some three months giving our personal attention to a certain Leading Ordnance Electrical Mechanic at his table – me acting for the defence! It was a great sadness to me that this book did not appear until after Admiral Watson passed away on 9 December 2009.

Patrick A. Moore

Commander (E)(WE) Royal Navy

FOREWORD

I am delighted to write the Foreword to this outstanding work by Commander Moore and congratulate him on his historical review.

I was privileged to be appointed as the Assistant to Rear Admiral Bateson at the inauguration of the Electrical Branch on 1 January 1946.

The initial report by Rear Admiral Phillips, the subsequent report by Vice Admiral Gervaise Middleton and the Bateson Report were the result of the rapid expansion of electrical technology, throughout the Fleet, during the Second World War. Experience had been gained by commissioned officers, artificers and mechanics and there was a danger that this expertise would be lost. The Admiralty Board realised the importance of ensuring that these skills, gained in war, were not lost to the Royal Navy in peacetime.

The result of these early initiatives was the formation of the Electrical Branch on 1 January 1946. The Electrical Branch has enabled the Royal Navy to take advantage of the design, development and maintenance of electrical systems as technology has developed, so keeping the Royal Navy at the forefront of modern weapon systems.

I have pleasure in recommending this excellent book.

Vice Admiral Sir Philip Watson KBE LVO CEng FIET CBIM

INTRODUCTION

In the vernacular of the Royal Navy, the term ‘Greenie’ has evolved to describe the officers and ratings responsible for the support of electrical engineering functions in the ships of the Fleet. Although the reasons for the term can be loosely traced back to the introduction of the dark green distinction cloth stripe for warrant electricians in 1918, it really took off as a nom de guerre soon after 1946 when the unified Electrical Branch was first formed and all electrical officers wore the green stripe. It was at this point that the electrical engineering expertise of the Royal Navy became concentrated into one branch and one department on board ship, charged with the provision of all electrical engineering support to any other department in need of the expertise.

Although The Greenie is essentially the story of the electrical officers and men of the Royal Navy, it will quickly become apparent to the reader that other national service institutions also made significant contributions to the advancement of electrical technology in maritime warfare. These institutions include (in their past and present forms) the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, the Royal Naval Scientific Service and the Royal Naval Engineering Service. Many members of these services paid the ultimate sacrifice for their country in the pursuit of their work. It therefore gives me great pleasure to include at least some details of their efforts and achievements in the Greenie story.

While the name of the Electrical Branch was changed in 1961 to the Weapons and Radio Engineering Branch, and in 1965 to the Weapons and Electrical Engineering Branch, autonomy for electrical engineering expertise remained with a single branch until technology advances, particularly in machinery control systems, dictated the need for a more radical branch restructuring. This came in 1979 when, under the auspices of Engineering Branch Development, an Engineering Branch comprising Weapons Engineering, Marine Engineering and Air Engineering Sub Branches was formed. This change was primarily managed by transferring the requisite number of ‘Greenies’ (electrical officers, ordnance electrical artificers, mechanicians and mechanics) into the Marine Engineering Sub Branch.

Further advances in technology in the late 1980s resulted in Warfare Branch Development which involved the restructuring of the Operations Branch and Weapons Engineering Sub Branch in 1993 to form a Warfare Branch which embodied the concept of the user-maintainer. The impact on weapon engineering Greenies was that all rates and specialist categories of weapons engineering mechanic were transferred into the new Warfare Branch and merged with Operations Branch ratings. This combined pool of ratings was used to populate an interim rating structure, needed to support ship Schemes of Complement, which had been redesigned to allow for the combination of the operation and maintenance duties of each branch. At the same time, an operator mechanic rate was established and a training regime designed to support seagoing billets with both user and maintainer responsibilities was introduced.

In 2007, most of these user-maintainer changes were revoked, leading to redefined operator -only specialisations remaining in the Warfare Branch and the return of the Greenies into a streamlined Engineering Branch organised to meet the Royal Navy’s needs for twenty-first century technical support. The streamlining involved the merging of the artificer and mechanic rates and all engineering ratings being given the new rate of ‘engineering technician’ but with specialist categories linked either to the weapon engineering or marine engineering functions as appropriate.

Despite this ebb and flow of electrical officers and ratings to the Marine Engineering and the Warfare Branches, the term ‘Greenies’ still lives on as a source of camaraderie, not for just those who originally formed the Electrical Branch but also the ‘electrical specialists’ who were embedded in those other branches. Perhaps more pointedly, it is still also used, but with more tongue in cheek endearment, by those retired and current members of the Royal Navy who still consider that the only real middle watch was the one spent on the ship’s bridge!

While The Greenie explores the origins of Fleet manning structures, technology and the management of that technology at sea from medieval times until the present day, there is a particular focus on the significant increase in electrical technology introduced into the Fleet during the period 1890–1990 and the establishment of the Electrical Branch in 1946.

Against the backdrop of technological advances and structural volatility, this book recalls personal memories of Greenie Branch history and offers anecdotal reflections on the role of Branch personnel during times of hostility and momentous change. Finally, a number of traditional naval yarns and cameos with an Electrical Branch flavour have been included in order to provide light relief, should it be needed, during a story which, hopefully, will bring back fond memories to the many involved and raise the interest of those who were not.

CHAPTER 1

EARLY HISTORY

Technology, the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, can easily be thought of as a modern phenomenon. However, it has always been there in some guise or other and it is probably only the rate of change which has altered since the beginning of time. From the steady evolution of ideas, we have now reached the stage where the introduction of new technology is almost at a frenetic level. No area is free from its influence and the Royal Navy is no exception.

Prior to the nineteenth century, the Royal Navy’s interest in technology was primarily based around the evolution of ship building and propulsion technology as applicable to the man of war, along with the specialist technology associated with the naval gun and navigation. It is these technological areas which helped form the initial manning structures aboard a warship, and some explanation of these generic beginnings is worth the reader’s time in order to understand the social politics which had such an impact in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on the way in which the Royal Navy was organised for the conduct of maritime warfare.

Ship Building

In broad terms, before the tenth century there were two types of seagoing ship evolving throughout the European continent, the galley and the sailing ship. Both types were being developed in a different fashion in two regions, northern Europe and the Mediterranean, with the latter examples evolving from as early as 5000BC beginning in Egypt. The way in which the two regions initially evolved their designs was very much dependent on the nature and availability of their land-based technology and the extent to which it could be transferred to the design and build of a ship. An example of this would be the carpentry techniques, which were more advanced and subtle in the Mediterranean region, and this showed in the way hulls were constructed. Another significant design driver was whether the ship was intended for military or commercial purposes with, arguably, early sailing designs being developed for commercial work and galley designs for the support of military activities.

Galley warfare. (Naval Historical Branch)

The earliest naval warships were the galleys. A notable difference between the northern European and Mediterranean designs was that there is little evidence of the former being fitted with decking or a ramming bow, either under the waterline or above it. Thus, the inherent military capability of each design was different: the early northern European galley was more of a troop carrier, while the Mediterranean galley was better equipped to attack other shipping with central walkways and, in later designs, additional decks built over the oarsmen for the deployment of men specifically carried for fighting at sea. Given these two distinctive features, tactically the use of these two types of galley would have been very different.

Galleys could be sailed under certain wind conditions but the main method of propulsion was the oar and numerous oarsmen. In some cases, these oarsmen would have been slaves but in others, primarily in northern Europe, free men were employed. The use of oars did allow some manoeuvrability in inshore waters but, as a means of fighting at sea, the ships were limited in capability as they could not easily close to board each other without risk to manoeuvring. The exception to this was the use of the bow ram which provided an offensive, ship-sinking capability and acted as a bridge onto the opposing vessel for boarding purposes. However, unless decked over, the galley could not often carry sufficient additional numbers of fighting men and these men were only able to board on a narrow front to attack the enemy. Generally in northern Europe the oarsmen were free men and part of the fighting capability, so once they had put down their oars and picked up their weapons there were obvious tactical constraints. In the ninth century King Alfred was successful in using galleys in his defence of England against the Danes. He achieved this mainly by using tactics such as blocking the waterway exit once the enemy ships had been beached and, with land troops in support, effectively surrounding the shorebound raiding parties.

By the tenth century, oared galleys were falling out of use in northern Europe. The Bayeaux Tapestry shows the hull form used for the Norman invasion of 1066 to be similar to the early Norse designs but with complete reliance being placed on sail and no evidence of any rowing capability. However, the rowed galley continued to be developed for warfare use in the Mediterranean until as late as the eighteenth century. In fact, the Mediterranean galley is believed to have been the first ship to have any heavy ordnance fitted. This occurred around the fourteenth century when the ‘Bombard’ – a form of cannon which fired stone balls weighing some 50lbs – was introduced by the Venetians. Although the cannon gradually replaced the ram as the primary means of galley warfare at sea, it was often constrained by the presence of seated oarsmen to firing only fore and aft.

A Norman galley as depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. (Naval Historical Branch)

Notwithstanding the occasional naval battle, the main reason for developing new ship designs was commerce. The fact that oarsmen took up space, had to be fed and, in the case of free men, paid, meant that the evolution of the galley was always going to languish because it was uneconomic for the transport of merchandise. The nature of the weather in northern Europe was also a factor against its development in that high seas were not the environment for using banks of oarsmen as the primary means of propulsion and the watertight integrity of the hull, with its numerous rowing ports, left much to be desired.

The first really effective craft for use as naval warships were single-masted ships which evolved from the type of sailing galley used by the Normans. This ship design was referred to as a ‘Cog’. They were also known as ‘Round Ships’, so called because they often featured on the round civic seals of many of the English ports. This representation tended to distort the impression of the hull into a walnut shape and did not give an impression of the great seaworthiness which was a feature of their reputation and the longevity of the basic design. In fact, the term ‘cog’ was probably a generic name which covered a number of similarly evolving northern European designs of the medieval sailing ship. The prime purpose of such a ship was commercial for they were designed to carry maximum amounts of cargo. However, they were also readily adaptable to the purpose of naval warfare.

The Civic Seal of Hastings, one of the Cinque Ports. (Hastings Museum)

What made the round ship suitable for military use were the high castle structures, usually fitted at the bow and stern of the ship, from which fighting men could launch missiles down onto the enemy once alongside at sea. The characteristics of castles, high freeboard and maximum use of hull space, meant that the ships were also ideal for high seas, commercial use when not co-opted into a military role. With the introduction of lightweight guns in the fifteenth century, this type of hull was the development baseline for the future ships of the line.1

Subsequent evolutionary drivers in design were the needs to increase the volume of the hull and speed through the water, both attributes being a requirement for longer range trading voyages and naval warfare expeditions. The conduct of these activities contributed further to ship design by giving more opportunities for the northern European and Mediterranean build features to cross-pollinate and evolve towards the most efficient and profitable design of sailing ship.

The Great Harry, an English carrack c.1545. (Naval Historical Branch)

One of these hybrid designs was the Carrack, developed in the fifteenth century by the Portuguese. Carracks were one of the first open ocean ships and they were used to explore the world by the Portuguese, Spanish and, in due course, the English. One notable example of the carrack was the Victoria, Magellan’s ship that first completed the circumnavigation of the globe in 1522. The ships were large enough to be stable in heavy seas and had enough hull space to carry the provisions and trade goods needed for long exploration voyages. The high castles used in the design made the Carrack very defendable against smaller craft, a great asset in less welcoming parts of the world, and the stable deck gave an effective gun platform. The downside of a high castle was that the ship had a tendency to topple in high winds and manoeuvring was also affected. The Carrack was used as the basis for the design of royal ships produced for the English Navy until the middle of the sixteenth century, such as the Henry Grace à Dieu, or more colloquially ‘The Great Harry’.

As more dedicated warships were built, two design requirements appeared which were not of great concern to the merchant fleet. The first was improved manoeuvrability and the second was greater hull strength to withstand the shocks of heavy gun operations and battle damage. These military requirements, plus the introduction of gun ports which allowed guns to be sited lower down in the ship, reduced the medieval high castle structures. This change improved windage across the bows and enabled the building of bigger ships with more guns capable of broadside firing. From the late sixteenth century, these fighting attributes were continuously developed and led to the iconic ships of the line that engendered the phrase ‘The wooden walls of England’ and dominated the naval warfare stage until the mid nineteenth century. The first HMS Collingwood provides a good example of the wooden hulled man of war at the peak of its development as pictured in an Illustrated London News article of 22 March 1845 (below).

In the mid nineteenth century, the next major change in ship building technology took place with the arrival of the ironclad hull. Iron hulled ships had been around since the late eighteenth century in the form of canal barges. Although the structural advantages were appealing, they were not immediately welcomed by the Royal Navy because of the problems with high seas navigation and action damage. The former became problematic because of induced magnetism in the iron hull distorting the earth’s magnetic field and affecting the accuracy of the magnetic compasses in use. The latter was of concern because early trials had shown that iron plates of the time would shatter causing splinter hazards inside the ship or, in some cases, exit holes which were so ragged as to be impossible to plug against water ingress.

The problem of magnetic interference was overcome in the late 1830s when Sir George Airey developed a system of compensating iron balls that could be adjusted around the magnetic compass to counteract the induced magnetism of an individual ship. With this innovation, the Admiralty started to warm to the idea of iron hulls and, by 1843, there were seven small iron ships in Royal Navy service with further orders placed in 1845 for four frigates of around 3000 tons. Unfortunately, a report on a series of firing trials,2 carried out against iron plating in 1846, again raised the profile of action damage concerns, such that the 1845 frigate programme was modified to convert the hulls to troop ships. However, the 1846 report did recommend that if the iron was backed with wood then splinter and exit damage would be reduced. In 1859, with this mitigation in mind, the Royal Navy started to build its first ironclad ship with a hull constructed using wrought iron plates backed by wood. The ship, HMS Warrior, completed build in 1861 and was fitted with a full sailing rig as well as a steam engine and propeller propulsion system.3 The ironclad hull proved to be a short lived building technique as steel technology quickly advanced to provide a form of armour plating which allayed much of the concern about action damage. The introduction of steel hulls removed the need for timber, cut down the ship build time and enabled the construction of bigger and stronger ships, which could carry larger weapons and new systems based on emerging electrical technology. Meanwhile, Warrior was declared obsolete in 1883 without seeing any action or justifying her acquired reputation as the most powerful warship of her time.

HMS Collingwood, Illustrated London News, 22 March 1845. (Collingwood Museum)

HMS Warrior in 1861. (Naval Museum Portsmouth)

Propulsion Systems

Although the use of oarsmen was a propulsion technique with its own place in the history of the galley, the main form of propulsion for the Royal Navy since its inception had been the sail.4 The response of the Admiralty to the application of sailing technology was very much hands off and for centuries it was left for seagoing captains to develop and adapt new concepts of harnessing wind power for maritime warfare. Their Lordships’ approach worked surprisingly well and many Captains were highly motivated – through the promise of prize money – to exploit the ship’s mast arrangements with new sail combinations or experiment with the trim of their ships to maximise sailing performance in order to successfully pursue and defeat the enemy. This enthusiasm was also actively supported by crews anxious to supplement the not too generous pay of the Royal Navy.

There were few formal processes for putting common standards into place and the spread of new ideas was often based on word of mouth, letters and reports of proceedings which announced successful naval operations. It was not until the nineteenth century that any land-based form of sail training was put in place and, ironically, it was not too long afterwards that the Royal Navy’s attention switched totally to steam propulsion.

The first steam-propelled ships were initially used by the Navy as tugs to assist sailing ships leave harbour in the face of head winds. One of the first of these was the naval steam vessel Comet which was built in 1822 and used as a steam training vessel before becoming a steam yacht for the Navy Board. In 1827, steamships started to be commissioned with the first warship, HMS Dee, appearing in 1829.

Apart from developing the use of the steam reciprocating engine as the prime motive force, the other technological debate at the time was whether the paddle wheel was more efficient than the propeller as a means of driving a ship through the water. Paddle wheel ships had been around since the late eighteenth century but the Royal Navy had only used them for support purposes as their seagoing performance, deck layout constraints and survivability were arguable for a fighting ship. By 1840, these open questions, along with rapid advances in screw propeller design from around 1800, had persuaded the Admiralty that the propeller was the way ahead and they started to place orders for a number of small screw-propeller-fitted ships in 1844. Notwithstanding this early confidence, largely for the benefit of the public, in 1845 it was decided to hold a series of trials using two ships, HMS Alecto and HMS Rattler, in a competition to establish which propulsion system was to be adopted for the Fleet. The two ships were of the same displacement and length and fitted with similar 200HP steam engines plus a sailing rig. The only significant difference was in the propulsion systems – Alecto had a side paddle wheel configuration while Rattler had a stern propeller fitted. The ships completed a series of time trials which involved the use of steam only, sail only and steam in combination with sail propulsion. The final, and most famous, trial engaged the two ships in a tug of war during which Rattler was able to pull Alecto astern through the water at some two knots despite her paddle wheels operating at full power. Throughout the trials, Rattler continued to demonstrate the superior efficiency of the propeller and, following this very public evaluation, the Royal Navy concentrated on a combination of the steam engine and the propeller, plus a sailing rig,5 as its preferred form of propulsion system.

Parsons’ Steam Turbine Engine destined for HMS Vanguard, 1907. (Naval Museum Portsmouth)

The next major advance in propulsion technology was the invention of the steam turbine, which eventually replaced the steam reciprocating engine. Although the principle of the turbine had been known for many years, the first modern steam turbine with marine propulsion applications was invented by George Parsons in 1884. As a ship propulsion system, it was initially fitted for demonstration in the Turbinia and appeared at the Diamond Jubilee Fleet Review in June 1997. The Parsons turbine was first fitted for the Royal Navy in HMS Viper in 1898, and subsequently it was used in HMS Dreadnought in 1906. Despite the advantages of economy shown by the steam turbine and the improved working conditions in the engine room, the steam reciprocating engine continued to be fitted in some Royal Navy ships until the end of the Second World War. The Loch Class was one of the last classes to be fitted with reciprocating engines and these ships saw service into the 1960s.

Naval Gunnery

In 1742, Benjamin Robins published New Principles of Gunnery, which introduced the science of ballistics, propellants and the effects on gun design. However, few of his ideas were implemented before the end of the eighteenth century and the naval gun continued to be developed around the concept of delivering an ever increasing weight of broadside to destroy the enemy. Poundage of shot was the British Fleet’s measure of power projection, and even during Nelson’s time the preferred option was to engage the enemy closely and fire as many broadsides at point blank range as possible.

It was often, once again, left to individual captains to innovate and take advantage of gun technology where they felt there were shortcomings in action. Robins’ works on the physics and mathematics of gunnery firings were understood by only a few enthusiasts and the gun presented a different form of technical challenge to that of maintaining the sailing performance of the ship. While the former could often be conveniently ignored, albeit at the risk of failure in battle, the latter was always open for peer and public scrutiny to the benefit, or otherwise, of a captain’s career.

It was the gunnery challenge that first generated a need for specialist onboard maintenance and training in the eighteenth century. The need for technological specialisation became more pressing with breech loading weapons, flintlock and electrical firing mechanisms, power operated training and elevating systems, centre line turrets and ammunition improvements being just a few significant examples of changes in gun technology introduced in the nineteenth century. Advances in gunnery and the application of technology in new warfare areas prompted the debate about how newly emerging electrical technology should be managed. One of the critical developments in gunnery was the exploding shell and its use at sea6 as wooden hulls provided little defence against such ordnance. The result of this innovation was to accelerate the introduction of the armoured steel hull, which was not only capable of withstanding solid shot7 but also offered the best defence against exploding shells. Later years would see the invention of the armour piercing shell, the response being to increase the thickness of armour. Thus battleship hull design started to evolve.

Emerging Electrical Technology

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the breadth and pace of technology advance throughout the Royal Navy started to increase rapidly. The Admiralty were obliged to cope with major changes such as the transition from sail to steam propulsion, and the move from wood to ironclad and then armoured hulls. The supremacy of the Royal Navy was being challenged by other growing navies’ use of technology, and any notion that technological advances could be ignored was quickly dismissed by the threats being perceived from those nations who sought to test the resolve of the Grand Fleet.

Within the dynamic technical environment of the nineteenth century the newly discovered uses of electricity were soon applied at sea. Following the initial introduction of the electrically detonated outrigger torpedo, other ship-borne applications for electrical technology swiftly began to emerge and these were soon to have an influence on the future development of the Royal Navy far greater than originally could have been predicted. For brevity, the term ‘electrical technology’ in this book refers to all forms of the engineering application of the phenomenon of electricity, including electronic, solid state, microchip and software technology.

HMS Excellent outrigger torpedo trials, Gig c.1860. (Naval Historical Branch)

Social Change

In parallel with technology changes, the nineteenth century also saw many social changes taking place. With the emergence of steam technology, naval officers, well versed in the art of fighting a sailing ship and usually possessing the same seamanship skills as their crew, found that their hard-won knowledge was no longer essential for conducting naval warfare as mechanical propulsion systems began replacing sail. With the arrival of the steam engine and the engineer, many of the traditional divisions between officer and rating started to be challenged. It was no coincidence that this occurred in parallel with the improvement in general educational standards. The lower classes, an historical source of rating recruits, seized the opportunity of the new technology to advance themselves. This energy fuelled the engine of the Victorian industrial revolution. With such newfound technical expertise, what had been considered the lower classes evolved social and professional aspirations that the Admiralty was to find an unstoppable force for change in the service.

As far as manning was concerned, the feudal system of the medieval era had been replaced in the eighteenth century by the ‘Hire and Fire’ approach to recruiting, which relied on the press gang and appeals to Jolly Jack’s sense of duty. In the nineteenth century it would have to change yet again and become more inclusive because of the technological needs of the Royal Navy which, to an extent, were anathema to many in the existing officer class. This new social enlightenment led to many questions about the Royal Navy as an employer and the answers raised demands for such things as improved living conditions, defined conditions of service, the supply of free uniforms, better rates of pay and more inclusive pensions in order to stop crews voting with their feet.

An HMS Bellona recruiting notice. (Collingwood Magazine Archives)

Payday aboard HMS Royal Sovereign c.1895. (Naval Museum Portsmouth)

Many ratings wanted the opportunity to gain a naval commission which, since the introduction of dedicated warships, had been awarded by the Admiralty to sea officers of lieutenant rank and above. The significance of this commission was that it identified that sea officers had been given Military Branch status and were qualified to take command of a ship. While a very few selected seamen who were employed in the fighting of the ship had the opportunity as the non-commissioned part of the military branch to gain a commission, other specialist professions were denied it and this was to be a continual source of debate well into the twentieth century. For the emerging engineers who did achieve commissioned status towards the end of the nineteenth century, another source of irritation was the fact that they, along with other non-seaman specialist professionals, were specifically categorised as Civil Branch officers and lacked parity in conditions of service and privileges with the officers of the Military Branch. Interestingly, issues of this nature had been first addressed by the Admiralty in 1731 when improved conditions of service were used to encourage the recruitment of the first gunnery specialists, but few further advances had been made before the advent of steam engineering. As Victorian society evolved in an increasingly technical era, the issues of status and career prospects started to become matters of concern for the rest of the men of the Fleet.

Thus, in addition to funding and implementing technology changes, the Admiralty was now finding itself obliged to consider the service conditions and branch structures that would best support the rapidly changing nature of the Royal Navy’s men of war and secure the manpower needed for its ships.

The Impact on Manning

The speed of technical advance during the industrial revolution meant that the Fleet quickly became comprised of ships fitted with a mix of old and new technology. Virtually each hull demanded a unique set of skills from the ship’s company and a tailored departmental structure for the effective deployment of those skills. Perhaps it was because of this rate of change and the broad variance in ship construction and outfit that the Admiralty adopted a ‘wait and see’ approach to implementing such things as shore-based training and the reorganisation of ship board responsibilities. It was not until the late nineteenth century that these matters were felt important enough to be addressed and some were not resolved until after the Second World War.

The task of organising the ship’s complement became more and more difficult as the introduction of different technologies, requiring diverse skills, grew rapidly from a trickle to a torrent. While this rate of change started to stabilise after the urgency of the Second World War, it did so at a level that still demanded constant management of manpower and skills in order to keep the Royal Navy at the operational forefront. This is still the situation today.

Managing the Technology

The purpose of this book is to review the way in which electrical technology was introduced into and managed by the Royal Navy up until the establishment of the Electrical Branch in 1946 and then to portray the evolution of the Branch until the end of the twentieth century. It was during this period that the Electrical Branch became more widely known as the ‘Greenie Branch’ and the officers and ratings forming the Branch became known collectively as ‘the Greenies’. The term also became synonymous with HMS Collingwood, the shore-based training establishment in Fareham, Hampshire, which became the training Alma Mater for the Electrical Branch.

While the Electrical Branch gave some stability to the provision of electrical engineering support at sea for some 30 years, the unstoppable tide of technology started to force major changes in branch structures in the late 1970s, the late 1980s and the late 2000s. Paradoxically, the first two major changes devolved certain aspects of electrical engineering support back into other branches, thus reversing some of the decisions made leading up to the creation of the Electrical Branch in 1946. However, the most recent change reintroduced an Engineering Branch with unitary electrical responsibility, somewhat ironically echoing the thoughts of the Engineer-in-Chief of the Royal Navy in 1945 during the debate about the creation of the Electrical Branch. It is also interesting to note that all of the cases for further branch restructuring were based on reasons not dissimilar to those existing in the mid 1800s, namely social as well as technological change.

HMS Collingwood commissioned as a wartime training establishment in 1940. (Collingwood Photographic Department)

CHAPTER 2

ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGY 1850–1938

Surface Weapons

From its introduction into naval warfare in the fourteenth century, the cannon was muzzle loaded with the size of projectile constrained by the amount of gunpowder that could be used as a firing charge without the barrel bursting. This limitation was due to the structural weaknesses inherent in barrels manufactured from cast iron. As casting techniques improved and better machining facilities became available, so cast iron barrels were produced which could accommodate bigger charges, with less risk to the barrel, and fire larger cannonballs.

By the early 1800s, the maximum size of cannon being used on board Royal Navy ships was the 32-pounder. Although a 42-pounder had been introduced in the late 1700s, it had been withdrawn from service because its weight meant that too many men were needed to operate the gun and the rates of fire were too low. Although the 32-pounder had a range of around 2,600 yards at an elevation of 8°, according to a range table produced in 1860 by the Gunnery School at HMS Excellent, it was normally used at lower angles of elevation and much closer ranges. At the time, cannon was categorised by the weight of cannonball – or shot – fired and the 32-pounder long gun was probably the largest gun that could be fired from a wooden hull owing to the forces being applied to the deck during firings. When the wrought iron barrel was developed in the 1850s, this paved the way for what became the largest cannon of its type, the 68-pounder. In all 26 68-pounder long guns were fitted on the lower deck of HMS Warrior in 1861.

As steelmaking technology and precision machining techniques advanced, so gun barrels were produced to much tighter manufacturing tolerances than the earlier cannon barrels. With these advances the concept of the modern naval gun, as opposed to cannon, was introduced, whereby the barrel required the addition of a breech mechanism and mounting arrangement. With the arrival of precision engineered barrels, the traditionally shaped shell replaced the cannonball as a more efficient design for harnessing the energy generated by the charge detonation and firing out to the maximum range possible. This type of gun barrel led to the introduction of a new method of categorising guns by calibre, based on the diameter (calibre) in inches of the bore of the barrel, virtually equivalent to the diameter of the shell being fired from the gun. The weight of both the 68-pounder cannon and the new concept gun were such that the mechanical forces acting on the ship’s structure on firing meant that they were only really suitable for mounting in iron-hulled ships.

68-pounder muzzle loading cannon in the HMS Excellent drill shed, 1896. (Excellent Museum)

In the 1770s, the carronade, a much lighter and shorter gun, was invented. It was produced in various sizes which could fire a range of shot from 6–68lbs. The design of the powder chamber was small for the weight of shot, which saved weight and reduced the muzzle velocity causing lower reaction forces on the ship’s structure. These features made the carronade suitable for mounting on the upper decks of a wide range of warships, including smaller vessels such as sloops and cutters. The shorter barrel and lower muzzle velocity made the carronade less accurate than the long gun but its heavier shot for size capability made it a devastating weapon at short ranges. Another advantage was that its relatively light weight made it more suitable for manhandling in battle and, when sited on the upper deck, it had a much wider firing arc than the long gun. However, by around 1820, as the ranges of the long gun increased the distance at which naval engagements were being fought, the limited range of the carronade started to make it obsolete as a naval weapon.

With the introduction of the gun port and the increasing weight of cannon, the disadvantages of fighting with muzzle loading weapons was soon recognised and this led to breech loading methods being investigated as early as the sixteenth century. However, the idea did not make much progress as the technology of the times could not achieve a gas-tight seal when closing the breech. It was not until 1859 that Sir William Armstrong developed a breech loading mechanism which, when assembled with his newly designed wrought iron gun barrel, formed the basis for modern naval guns. Armstrong’s gun had a barrel with a calibre of 7 inches and it could fire a 110lb shell. Another innovative feature was that spiral grooves, or rifling, had been machined into the internal surface of the barrel. The rifling was designed to exert a spinning force on a lead-coated shell as it passed through the barrel. The spinning induced by the rifling helped to stabilise the shell in the air and improve ballistic accuracy. Eight of the new Armstrong 7-inch breech loading rifled (BLR) guns were fitted in Warrior.

Unfortunately, the Armstrong breech proved prone to overheating and it failed to such an extent that a Parliamentary Ordnance Select Committee was tasked to investigate the matter. The Committee reported in 1865 that ‘The many-grooved system of rifling with its lead-coated projectiles and complicated breech-loading arrangements is far inferior for the general purpose of war to the muzzle-loading system and has the disadvantage of being more expensive in both original cost and ammunition.’ Accordingly, the production of the breech loading gun was stopped and the Royal Navy was obliged to revert to muzzle loading guns. While muzzle loading was deemed more reliable, it had the operational impact of reducing the rate of fire achievable from the major calibre guns appearing on the scene. A typical 8-inch shell weighed around 250lbs and this required some form of mechanical ammunition supply and ramming arrangement. Gaining access to the muzzle, either by training over a clear deck or depressing the barrel to a compartment below the weather deck, made the reload process not only more complicated but also more protracted.

68-pounder breech loading cannon in the HMS Excellent drill shed, 1896. (Excellent Museum)

An interrupted thread breech block arrangement c.1880. (Excellent Museum)

In 1880, the interrupted thread breech was invented. This design sealed the breech more effectively than its predecessor and proved to be more reliable in service. As a result, breech loading was re-adopted, but only for guns where rate of fire was deemed operationally critical. This became more applicable to smaller calibre guns which, by virtue of the limited hitting power of a single shell, relied on higher rates of fire to deliver destructive amounts of explosive against surface targets.

As ship hull construction evolved from iron clad to steel and finally to armour plated hulls, so the demand for bigger calibre guns mounted on larger, faster ships increased. From the 7-inch gun of 1859, calibres increased in a series of steps to reach 16.25 inches in the guns fitted in the Royal Navy’s Admiral Class battleships built in the 1890s. While this dash for major calibre guns no doubt had some operational justification, there is evidence that it was more often driven by perceptions of the political importance of gun weight and shell size amongst the global sea powers.

HMS Benbow with 16.25-inch barbette mounting, 1885. (Naval Museum Portsmouth)

Prior to 1860, naval guns could only fire on fixed – or very limited – bearings with the ship being manoeuvred to bring the guns to bear. These firing bearings were mostly on the beam, but bow and stern chasers were also fitted to give fore and aft channels of fire. What were known as ‘transferable’ gun mountings with improved arcs of training were gradually coming into use. These guns were usually mounted on manual or steam driven turntables and could be turned to align with gun ports in the ship’s hull and, later, in an armoured enclosure for firing to take place. Initially, the enclosures were either ‘turrets’ or ‘barbettes’. The early turret was fixed and fully enclosed the gun with firing arcs being limited by the gun port positions. The barbette was an open topped structure which allowed the gun to be raised for firing with arcs limited only by the ship’s superstructure. In due course, the turret itself became trainable and carried the gun giving the benefits of both wide firing arcs and full armour protection. This rotation capability also enabled the correction of convergence at close ranges.8

One of the first trainable gun mountings was installed in HMS Inflexible. The ship was fitted with four 16-inch guns in twin mountings which were installed midships ‘en echelon’,9 to allow at least three of the four guns to be used in fore and aft engagements. The designated main forward firing mounting was on the port side of the ship and the aft firing mounting on the starboard side. Despite a narrow superstructure designed to allow three of the four guns to be brought to bear, it was found that firing ahead or astern still led to considerable blast damage to the ship. The echelon configuration was eventually abandoned in favour of centre line mountings.

Since the introduction of the gun port in the seventeenth century, the broadside engagement at close quarters had been the accepted method of engaging the enemy at sea. The primary reason for this was that while a synchronised firing of all cannon at maximum range was deemed to be the most effective method of engagement, the gun smoke generated invariably caused loss of sight of the enemy and any subsequent firings were only of much use if conducted at point blank range. This range removed any real need to aim the gun and meant that firing was left to the independent control of a local gun captain. Although not technically available at the time, the solution was to have the actual firing of the guns under the direct control of an officer stationed at a remote position which was clear of gun smoke. Such a system would allow broadside engagements at greater ranges, continuous observation of the enemy’s position and assessment of the fall of shot for range correction.

HMS Inflexible at Malta, 1883. (Naval Museum Portsmouth)

Electrical vent sealing tube sketch. (Collingwood Museum)

It had already been discovered that heat, not just flame, could be used to set off an igniter charge and with the reintroduction of the breech loading gun in the mid nineteenth century came the first major advance in the firing of the gun since the use of the flintlock at the turn of the century. This firing system came in the form of the vent sealing tube (VST) which was inserted into the propellant charge either through the breech mechanism or down through the top of the barrel. The tube contained a method of generating heat which then set off a flash charge that was directed down the tube to initiate the igniter material contained within the main propellant charge. One of the early types of VST was based on the heat produced by the friction generated when a goose quill was pulled through the copper tube by a lanyard. Although mainly used by the British Army until the end of the nineteenth century, the Royal Navy had used this type of tube in muzzle loading cannon but it did not resolve the perennial problem of remote fire control and the synchronised firing of guns as a broadside or, as it was known later, a salvo.

In 1800, Alessandro Volta invented the Voltaic Pile Battery and from this grew the science behind electrical and chemical phenomena known as electrochemistry. The electromotive force, or voltage, of the early batteries was of limited use outside the laboratory. However, by the mid 1800s the voltages being achieved were found to be sufficient to produce a heating effect which had the potential for use in the detonation of explosive material and the development of an electrically operated VST. At last the Royal Navy saw a potential solution to their problem of a remotely operated, electrically powered firing system for use on board ship. Eventually a Voltaic Pile Battery consisting of 120 cells was found to have enough voltage to make it suitable for the task of quickly heating a fusible link and initiating the igniter material inside a charge of gunpowder being used as a propellant.