11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

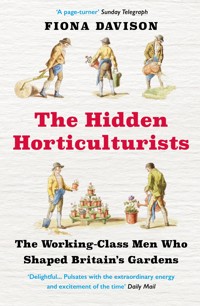

'Delightful... The Hidden Horticulturists pulsates with the extraordinary energy and excitement of the time.' Daily Mail Chosen as one of the Sunday Telegraph's 'Top Ten Gardening Books of the Year' _____________________ The untold story of the remarkable young men who played a central role in the history of British horticulture and helped to shape the way we garden today. In 2012, whilst working at the Royal Horticultural Society's library, Fiona Davison unearthed a book of handwritten notes that dated back to 1822. The notes, each carefully set out in neat copperplate writing, had been written by young gardeners in support of their application to be received into the Society's Garden. Amongst them was an entry from the young Joseph Paxton, who would go on to become one of Britain's best-known gardeners and architects. But he was far from alone in shaping the way we garden today and now, for the first time, the stories of the young, working-class men who also played a central role in the history of British horticulture can be told. Using their notes, Fiona Davison traces the stories of a selection of these forgotten gardeners whose lives would take divergent paths to create a unique history of gardening. The trail took her from Chiswick to Bolivia and uncovered tales of fraud, scandal and madness - and, of course, a large number of fabulous plants and gardens. This is a celebration of the unsung heroes of horticulture whose achievements reflect a golden moment in British gardening, and continue to influence how we garden today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Fiona Davison, 2019

The moral right of Fiona Davison to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All illustrations are from the RHS LindleyCollections, except where noted.

Endpaper image: Flower garden at Valleyfield in Scotland by Humphry Repton, 1805. Several of the young men worked at Valleyfield before coming to train at Chiswick.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-507-5E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-509-9Paperback ISBN: 978-178649-508-2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

FOR PATRICK, LIAM AND JOEL

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE‘The Handwriting of Under-Gardeners and Labourers’

INTRODUCTIONA Garden to Grow Gardeners

CHAPTER ONE‘The beau ideal’: The Horticultural Elite

CHAPTER TWO‘Much judgement and good taste’:The Gardeners Who Set Standards

CHAPTER THREE‘A great number of deserving men’:Life Lower Down the Horticultural Ladder

CHAPTER FOUR‘The most splendid plant I ever beheld’: The Collector

CHAPTER FIVE‘Much attached to Egypt’: Travelling Gardeners

CHAPTER SIX‘Young foreigners of respectability’: Trainees from Abroad

CHAPTER SEVEN‘A little order into chaos’: The Fruit Experts

CHAPTER EIGHT‘For sale at moderate prices’: The Nurserymen

CHAPTER NINE‘A solitary wanderer’: The Australian Adventurer

CHAPTER TEN‘Habits of order and good conduct’:The Rise and Fall of a Head Gardener

CHAPTER ELEVEN‘A very respectable-looking young man’: Criminals in the Garden

EPILOGUE‘Glory has departed’: What Happened Next?

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

INDEX

Acknowledgements

WRITING A BOOK IN MY SPARE TIME INEVITABLY means that I have relied very heavily on the support of lots of people. I could never even have contemplated a project like this without access to digitized collections from a number of libraries and archives across the globe. The availability and accessibility of these collections relies on the dedicated labour of countless skilled and committed staff members and volunteers, and every researcher owes them an enormous debt.

I am especially grateful to the archive staff at Royal Botanic Gardens Kew and Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, who sent through so many digital files of scanned correspondence and minutes. Leonie Paterson and Graham Hardy were particularly helpful and I really enjoyed the opportunity to visit them to see the site of James Barnet’s home. My colleagues in the RHS Libraries team have also been very supportive (as, of course, they are to hundreds of researchers every year), helping to track down images and sources. It has been a treat to witness their expertise and enthusiasm from ‘the other side of the fence’. Dr Brent Elliott has provided invaluable support in reading and meticulously checking early proofs – any remaining errors that have managed to slip through are, of course, my own responsibility. I have relied heavily on his pioneering work on Victorian gardening. I have also drawn upon the genealogical research expertise of my mother, Ann Thornham, in particular her determination to track down the runaway Annie Slowe, long after I had given up on her.

I also have to thank London Broncos Rugby League Club for use of their clubhouse to work in, on many evenings whilst I waited for my son Joel to finish training. This is what the strange woman in the corner with the laptop was up to.

This project would never have made it into book form without the faith and encouragement of Rebecca Winfield of Luxton Associates, who has expertly guided me through the mysteries of the publishing world. James Nightingale and the team at Atlantic Books have been great to work with as a first-time author, and I am delighted that this is a co-publication with RHS Publishing – my thanks to Chris Young and Rae Spencer Jones in the Editorial Team for making this possible.

Finally, my thanks and love to Patrick, Liam and Joel for their patience on the many occasions that my attention was distracted by 105 long-dead young men.

PROLOGUE

‘The Handwriting of Under-Gardeners and Labourers’

Thomas McCann admitted 22 June 1822 upon therecommendation of Sir Aubrey de Vere Hunt.

My father at the time I was admitted to the garden of the Society, was a gardener to Sir Aubrey de Vere Hunt of Currah in the County of Limerick. I was born at Galls town in the County of Dublin and was employed in Sir Aubrey de Vere Hunt’s gardens and Nurseries from the age of 14 til I was 18, I then worked in London Nurseries for 8 months after which I came to the garden of the Society then 19 years of age and unmarried.

First entry in ‘The Handwriting ofUnder-Gardeners and Labourers’ book

IN 2012 I STARTED WORK AT THE LINDLEY LIBRARY in London, which is the main library and archive of the Royal Horticultural Society and the largest and finest horticultural library in the world. In my first weeks I wandered through the stores, trying to understand what I had let myself in for. I saw a dizzying array of garden-related treasures, the fruits of the Society’s 200-year-old obsession with plants and gardens. Sumptuous botanical illustrations, imposing leather-bound herbals and garden designs were piled high on the shelves in the library storerooms. However, the item that intrigued me most in those first weeks sat in a rather unprepossessing cardboard box on a shelf in my new basement office, labelled in pencil ‘Handwriting Book’. Inside was a slim cardboard-backed exercise book with a marbled cover and a maroon leather spine. A bit dog-eared at the corners, it looked like a standard piece of Victorian office stationery, apart from the title, which was embossed rather grandly in gold letters on a leather label on the front of the book: ‘The Handwriting of Under-Gardeners and Labourers’. Inside was exactly that – 105 handwritten notes signed by young gardeners, spanning the years 1823–9 and recounting their working experience from the age of around fourteen until they were ‘received into the Society’s Garden’.

Each entry covered the young gardeners’ careers from leaving school to the point where they had completed their early apprenticeship. Starting with their place and date of birth and their father’s occupation, the short handwritten paragraphs outlined how the young men worked their way up through the different departments of a series of large gardens and commercial nurseries, gaining experience of ornamental flower gardens, kitchen gardens, hothouses and nurseries. Each entrant had to be recommended by a Fellow (a member of the Horticultural Society; the list of recommenders reads like a roll call of the aristocracy and the gardening elite). The entries in the Handwriting Book give a fascinating insight into the career structure of early nineteenth-century horticulture, revealing professional hierarchies and patterns of patronage, and interconnections between different gardens and nurseries across the country.

Even though the book was clearly written to a formula, the men’s voices and stories shone through, a rarity from a time when most ordinary working people were voiceless and anonymous. From the first flick through, I was smitten and became determined to know more. What was this garden, and why did the Society take on so many gardeners to work in it? Why did it make them write down their CV by hand in this book when they started work? And what happened to the gardeners after they had thrown in their lot with the Horticultural Society and been ‘received into the Society’s Garden’?

The answers were sometimes hard to find. After the brief glimpse into their lives offered by the Handwriting Book, many of the men became elusive once more. By and large, they were not the type of men to write autobiographies, diaries or even long letters. Fleeting glimpses of them appear in newspaper articles, plant and garden descriptions and of course in the national census – that frustratingly slow stop–go animation, where the shutter clicks on a new frame every ten years, leaving the viewer desperately trying to fill in the gaps between the changed scenes: a shift in location, new occupation, new wives, tragic missing children. However, little by little the men began to reveal themselves, and the legacy that they left on our landscape and our gardens came into focus. Little did I know it, but following their trail was to take up most of my spare time over the next three years, and the trail was to stretch from west London to Bolivia and all points in between, taking in fraud, scandal, madness and, of course, a large number of fabulous plants and gardens.

These young men were fortunate enough to begin their careers in a remarkable garden at a time of enormous optimism and ambition. Britain’s position as an imperial power – and her command of the trade routes – facilitated the discovery and importation of an enormous number of new and exotic plants. The discovery of new plants would have been of purely academic interest, if gardeners had not worked out how to grow them back home. However, scientific progress gave them the confidence that they could gain the upper hand over nature, particularly as new manufacturing technologies enabled the building of effective glasshouses to overcome the limitations of the English climate. Although the elaborate and mannered style of Victorian garden design and the highly labour-intensive practices that Victorian gardeners followed are both now long out of fashion, the evidence of the period’s innovations still flourishes in our gardens. From tender bedding plants to repeat flowering roses, we take for granted plants that the men from Chiswick helped to develop and promote. Although they are now by and large forgotten, unearthing their stories has revealed that these men helped to shape our idea of the domestic garden.

NOTE

The process of translating historic monetary values into modern terms is a complex one, and since it happens several times in this book, I thought it worth explaining how I have approached it. Context is everything – to really understand what any given sum of money is worth to someone in the past, we need to comprehend its purchasing power at the time. A simple method, often used, is to multiply the sum by the percentage increase in inflation over the period, but this may be misleading. Inflation (the Retail Price Index) is based on the price of a notional ‘basket’ of goods. Our consumption patterns have changed so much that by the time you get back to the 1820s, this can be an unreliable measure. I have tended to use the ‘labour value’ as the multiplier – that is, measuring the amount relative to the earnings of an average worker, based on data from a wide range of studies, supplied by MeasuringWorth (a not-for-profit organization aiming to assist researchers in making value comparisons). If you are at all interested in the topic, I can heartily recommend the essays on their website, measuringworth.com.

INTRODUCTION

A Garden to Grow Gardeners

THE STORY OF THE HANDWRITING BOOK BEGINS IN a vegetable field near Chiswick on a June day in 1821. The field was located on a flat piece of ground of around thirty acres (twelve hectares) close to the banks of the Thames, between the hamlet of Turnham Green and the northern wall of the Duke of Devonshire’s house, Chiswick Park. Treading their way through the rows of vegetables, a small party of four middle-aged men were making a tour of inspection. At this time Chiswick was a sleepy village on the western edge of a ring of market gardens that ran almost uninterrupted from Tothill Fields in the City on the north bank of the Thames, through Pimlico, Chelsea, Kensington, Fulham, Parsons Green and Hammersmith. Unlike the workmen bending to weed between the rows of early cauliflowers, the four men in view were clearly gentlemen. The party’s leader was a distinguished-looking balding man in his early sixties. This was Thomas Andrew Knight, president of the Horticultural Society of London and an acknowledged authority on fruit trees. This unassuming market garden was an unlikely place to draw such an esteemed figure to make the long journey from his estate in Herefordshire.

Knight had an unusual upbringing. His father, a Herefordshire clergyman, had died when he was only five, and his early education was neglected to the point that he was still virtually illiterate at the age of nine. However, he was intelligent, observant and fascinated by plants from an early age. Even though he led a retired life on his estate, he developed such a reputation as an expert plant physiologist and horticultural innovator that the great botanist Sir Joseph Banks sought him out and encouraged Knight to take a hand in the establishment of the new Horticultural Society of London. Having set out the objectives of the new Society, Thomas Knight was elected president in 1808. Although he was described by those who knew him as reserved and painfully shy, a careful observer on that summer day in Chiswick might have detected subtle signs of mounting enthusiasm. Knight’s knowledgeable eye will have taken note of the fertile alluvial soil, which had been exploited by market gardeners for decades to grow fruit and vegetables for the London capital.

It is likely that the party also included an angular gentleman with a sharp, patrician profile. Joseph Sabine was cut from a very different cloth from the retiring Thomas Knight. An assertive and energetic man, he had been the driving force behind the day-to-day operation of the Society since he first became its honorary secretary in 1810. He was a member of a prominent Anglo-Irish family based in Hertfordshire and, in addition to holding the position of Inspector-General of Taxes, was a keen naturalist and horticulturalist and a founding member of the Linnean Society. He was one of the strongest advocates for the acquisition of a garden. As the party made its tour of inspection, the conviction grew that perhaps at long last the Horticultural Society of London could make the step from being a ‘talking shop’ – publishing theoretical papers and reviewing the fruits of other people’s gardening endeavours at its regular meetings – to being a hands-on participant in the drive to experiment and develop modern horticulture.

The Horticultural Society had been operating for sixteen years by this point. It was founded in 1804 with the aim of ‘the Improvement of Horticulture’.1 The agricultural and industrial revolutions begun in the previous century were gathering pace and were being accompanied by social and scientific revolutions that were to be just as far-reaching. New wealth and prosperity, together with a widely held belief in rational, scientific progress, was fuelling a boom in interest in both botany and practical horticulture. In the eighteenth century, American plants were introduced to Britain in increasing numbers, and James Cook’s three voyages of discovery across the Pacific between 1768 and 1779 had given a tantalizing peek at the botanical treasures to be found in far-flung lands. From 1815 onwards, with the burden of war with Napoleonic France removed, Britain was to find itself at the heart of an unprecedented period of exploration, trade and conquest, which was to create routes for new plants to arrive in the country at an almost unbelievable rate. It was in this heady atmosphere that the Horticultural Society of London was founded by Sir Joseph Banks (who had made his name as a botanist on Cook’s voyage to Australia) and John Wedgwood (part of the entrepreneurial pottery dynasty). The Society aimed to develop horticulture as a science rather than a craft, and to base practice on empirical observation rather than folklore and tradition. In common with other learned societies set up at around this time, it had the culture and structure of a gentlemen’s club.

In 1818 the Society had decided to set up a committee to look into the possibility of establishing a permanent garden. By this time the Society had accumulated a variety of plants donated by well-wishers and had been forced to rent a walled market garden, opposite Holland House at the south side of the Hammersmith Road, in which to keep them. However, the Horticultural Society was forced to admit that real success depended upon ‘the establishment of an extensive Garden, in which plants may be placed, their peculiarities honestly remarked and the requisite experiments carried under the immediate superintendence of its officers’.2 This trip to Chiswick was to inspect land owned by the Duke of Devonshire, which he had offered to rent to the Society for a period of sixty years at £300 a year. This was to become the Society’s first proper garden. The Society later stated that the site had been preferred over other possibilities because of the suitability of ‘the tenure, situation, the quality of the soil, the easy supply of water and every circumstance connected with the land’.3 During the negotiations for the lease, the Duke of Devonshire insisted that a private door was installed in the wall separating the Garden from the grounds of Chiswick House, so that he could visit at his leisure. For one young gardener listed in the Handwriting Book, this doorway was to be the portal to a life of fame and fortune.

But that was several years away. In 1821 the flat fields near Turnham Green were far from being the showcase of horticultural excellence and innovation that the Council of the Horticultural Society aspired to. An appeal was issued to Fellows to raise funds for the formation of a garden. His Majesty the King got the ball rolling with a pledge (never actually honoured) of £500. The initial response to the appeal was good, and by April 1823 contributions totalled £4,891. Plans were drawn up and approved by the Council. The Garden was to be split between a ‘department’ for fruit and vegetables and an ‘ornamental department’, the majority of which was given over to an arboretum of eight acres (3.2 hectares). Of course it was realized at the time that the establishment and stocking of the Garden would only be the beginning of the expense. In 1823 the Society estimated that the annual cost of running the Garden would be in the region of £1,200 (around £1 million in today’s money).

Plan of the arboretum at Chiswick – in a report on the Garden of the Horticultural Society, 1826.

The key to the creation of the Handwriting Book was that this ambitious garden was always intended to be more than just a place to raise interesting plants. Even before the lease was signed, the Society proudly announced that it intended that its Garden should become ‘a National School for the propagation of Horticultural knowledge’.4 The young men listed in the book were its first students. Such a school was needed because there was a general feeling that standards of knowledge were too low. Writing thirty years later, the eminent head gardener Donald Beaton declared that in the mid-1820s ‘some of the best gardeners in the country did not know or understand the principle of potting plants’.5 In the previous generation, when Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown’s vision dominated the great estates, it was enough to have a head gardener who could keep the rolling lawns neat and manage the kitchen garden competently, in the tried and trusted manner of his forefathers. However, in keeping with the spirit of experimentation and improvement, the horticultural world now demanded a new type of gardener.

So the flat vegetable fields of Chiswick were to be the base for a garden that would ‘grow’ gardeners as well as the very latest garden plants. In February 1822, just seven months after agreeing to take on the Chiswick plot, the Society issued a ‘Statement relative to the Establishment of a Garden for the Information of Members of the Society’ to lay out the Society’s aims and, presumably, drum up more donations to support the resulting work. It is in this document that we gain an early glimpse of the way the Council saw the ‘National School of Horticulture’ operating. It was declared that while the head gardeners would be ‘permanent servants of the Society’, the under-gardeners and labourers would be ‘young men who having acquired some previous knowledge of the first rudiments of the art, will be received into the Establishment, and having been duly instructed in the various practices of each department, will become entitled to recommendations from the officers of the Society to fill situations of Gardeners in private or other establishments’.6 The Society envisaged that, over time, the great gardens of the kingdom, and even the wider Empire, would be staffed with gardeners who had been trained at Chiswick. A powerful alumni would be created that would take the influence and reach of the Horticultural Society far and wide, in the process raising standards of horticulture across the globe.

From the very beginning, it is clear that there was a high demand for places. The reputation of the Horticultural Society of London as the nation’s key authority on horticulture was already established, and the Chiswick Garden acted as a magnet to all the best and brightest young gardeners. The first Report of the Committee set up by the Society to oversee the running of the Garden, published in 1823, announced that ‘applications for employment have been very numerous’. The very existence of the Handwriting Book shows that the Society was serious about selecting only the best candidates; it was intended to be a means of both demonstrating and recording that the men who were accepted met the Society’s criteria for admission. The entries were written to a formula, dealing one by one with the different entry criteria, although the men clearly had freedom to use their own wording. Every man had to be recommended by a Fellow of the Society, though many seem to have come via Joseph Sabine, as his name is given as the recommender for thirty of the nominees.

The most fundamental way in which the Handwriting Book fulfilled its function as a record of the men’s eligibility was by clearly demonstrating that they were literate, as each young man had to write his full CV in his own hand. Literacy was the bedrock for the improvement that many sought to see in the field of horticulture. This was a subject very close to the heart of one employee of the Society. At around the time the Horticultural Society took on the land at Chiswick, it appointed a young man to become assistant secretary in charge of the collection of plants in the new Garden. At just twenty-three, John Lindley was of a similar background and age to many of the men who were listed in the Handwriting Book. He was born in Catton, near Norwich, in 1799, the son of a nurseryman whose business struggled and left the young John saddled with debt. Whilst he learnt the basics of horticulture from his father, Lindley was hungry for knowledge and, in addition to the Latin and Greek he was taught at Norwich Grammar School, he also studied French and drawing skills from a French refugee. Despite the misfortune of blindness in his left eye, Lindley was a talented artist, but above all was a workaholic devoted to botany. Through diligence and hard work he became a leading authority on botany, and orchids in particular. His personal experience convinced him of the value of educating gardeners, whatever their background, and of the importance of a meritocratic approach to ensure progress. He was instrumental in encouraging the young gardeners to form a Mutual Improvement Society in 1828, and in creating a small library for the gardeners to consult in the Chiswick Garden. The Council agreed to support this with a generous grant of £50 for books, and voted that the term ‘Labourer’ should be replaced by ‘Student’ when referring to the young men.

Pen and ink portrait of John Lindley, Assistant Secretary of the Society, drawn by his daughter Sarah in around 1850.

One of the most zealous campaigners for the education of gardeners and working men in general was John Claudius Loudon. Like Lindley, Loudon was possessed of an astonishing level of energy, for he was a garden designer, landscape architect and the leading horticultural journalist of his age. He took a close interest in the Chiswick trainees and monitored the operation of the Horticultural Society Garden closely in the pages of his Gardener’s Magazine. He wrote that it was essential for a young gardener to ‘cultivate his intellectual faculties’. Reading widely and studying deeply were vital for professional progression, otherwise ‘if he remains content with the elementary knowledge… as gardener lads acquire under ordinary circumstances, he will assuredly never advance beyond the condition of a working gardener, and may not improbably sink into that of a nurseryman’s labourer of all work’. According to Loudon, a ‘gentleman’s gardener’ would need ‘not only be a good practical botanist, but possess some knowledge of chemistry, mechanics and even the principles of taste. Instead of being barely able to write and guess at the spelling of words, he will never be admitted, even as a candidate for a situation unless he writes a good hand, spells and points correctly, and can compose what is called a good letter.’7 This gives a clear idea of the calibre of men the Horticultural Society was hoping to attract. The quality of handwriting, spelling and grammar throughout the Handwriting Book is generally very high.

The vast majority of the entries start with the writer describing the occupation of his father. In 1823 the Society had announced that ‘In the selection the preference will be given to the sons of respectable gardeners’.8 To twenty-first-century eyes, accustomed to initiatives to broaden access to professions, this focus on ‘keeping it in the family’ feels alien. However, for most of the nineteenth century, people saw nothing unusual or negative in professions being stocked from a limited range of families. Sons of gardeners were likely to have the basic grounding in gardening that the Society required, as they would have been surrounded by the processes and paraphernalia of horticulture from the earliest age. This was an initiative to raise the quality of horticulture, and not necessarily to broaden its base. However, despite the decision to prioritize recruiting the sons of gardeners, less than half (45 per cent) of the men in the Handwriting Book had a father or other close male relative working as a gardener. The majority of the intake to Chiswick were not simply following the family trade, but were entering the horticultural profession from scratch. This is all the more remarkable since, at the time when the Horticultural Society was recruiting, the profession of gardening had not reached the status it was to attain later in the nineteenth century. Although Capability Brown had demonstrated that it was possible for someone with relatively humble origins to use horticulture as a springboard to fame and wealth, he was very much the exception to the rule.

Portrait of John Claudius Loudon from his book Self Instruction for Young Gardeners, published in 1845.

To see why a career in horticulture was such an attractive prospect to bright young men from working-class backgrounds it is worth looking at the state of the economy in the early 1820s. Ten of the young men described their father’s occupation as ‘farmer’, and their decision to look to horticulture rather than agriculture for a living reflects the fact that this was a time of severe economic hardship in many rural areas, particularly for those with small farms. Returns from agriculture were depressed, as grain prices tumbled to less than half the levels they had attained during the years of scarcity caused by the Napoleonic Wars (1799–1815). At the same time, improved methods of agriculture had increased yields, leading to higher supply of produce, which in turn depressed prices. The process of Enclosure, whereby landowners used parliamentary legislation to consolidate small open fields into bigger ‘enclosed’ units, deprived many young men of the opportunity to follow their fathers as tenants of small farms. And it was not just farmers who suffered. In parts of the country there was severe unemployment as the British economy struggled to absorb the thousands of men who were discharged from the army, navy and militia at the end of the wars, and there was considerable worry about gangs of unemployed young men roaming the countryside looking for casual work. Average rural labourers’ wages fell from around fifteen shillings a week to around nine shillings, and many families found themselves on the verge of starvation.

Additionally Parliament, dominated by the interests of the landowning elite, pushed through import duties on malt, butter and cheese – taxes that were most keenly felt by the poor. The Corn Laws that restricted grain imports further guaranteed the incomes of large landowners. Tensions rose steadily through the period when the men were writing their entries in the Handwriting Book. By 1830 landowners, parsons, overseers of the poor and better-off farmers were being terrorized by letters signed ‘Captain Swing’, threatening retribution for their perceived exploitation of the rural poor. Mobs were breaking threshing machines, burning barns and demanding higher wages and more employment. The growing industrial towns and cities of the North pulled a lot of young people from the countryside, although everyone was well aware that the streets of Manchester, Birmingham and other cities were far from being paved with gold. In this context, it is easy to see why entering a skilled trade such as horticulture had its attractions. Thanks to their privileged position and manipulation of the political system, landowners had the disposable income to maintain larger and more extravagant households, which meant that domestic service, indoors or outdoors, was a growing employment sector. Gardening offered the prospect of accommodation, relatively steady employment and, if you made it to the position of head gardener of a large country-house garden, status and a good income.

* * *

By the time the men were writing their entries, they had already committed a great deal of time and effort to advancing their horticultural training. The Society required that ‘They will be young men who have been previously educated as gardeners, but who have not previously held situations as such.’9 In practical terms, this meant they were looking for men who had been through their apprenticeship and were what was known as ‘journeymen’ gardeners. There was an accepted route for young men to become professional gardeners and it appears, from entries in the Handwriting Book, that most of the men accepted to work and study at the Chiswick Garden had followed a similar career path. At around fourteen a boy would be apprenticed to a gardener for around three years. Although the vast majority of the men in the book were at school until that age, some apprentices were as young as twelve, and it is likely that these boys would still be spending part of the day at school. In return for their labour whilst they were apprentices, they received instruction, food and very basic lodgings. This was a hard life, as an apprentice boy was expected to do the repetitive, basic jobs that needed doing in every large garden – washing pots, sweeping paths, weeding, lighting fires and stoking boilers. He would spend time in the different departments of the garden, learning by watching and doing.

At the end of the apprenticeship the young gardener would then expect to move on to spend time in a range of distinct situations, to get a fully rounded horticultural CV. This was a peripatetic life, something akin to a series of internships. A young gardener would be expected to spend around at least a year in a number of establishments, changing jobs to develop skills in the different branches of horticulture – propagation, fruit growing, hothouse operations, and so on. A very ambitious gardener would try to work in a broad range of different environments, which might include a public botanic garden, a nursery and a private garden. Some were known as good ‘teaching gardens’, meaning that the head gardener was well known and respected as knowledgeable and inclined to teach rather than exploit his young charges, and the garden itself was fitted out with the latest equipment and stocked with a good range of plants. Notable teaching gardens that reappear time and again in the Handwriting Book include Cassiobury in Hertfordshire, Valleyfield near Dunfermline and Haddo House in Aberdeenshire.

The Handwriting Book includes several entries where it is clear that the writer has made a distinct effort to extend his knowledge and experience in this way, sometimes travelling far and wide to do so. Loudon recommended that when a young journeyman needed to move on to his next garden, he should ‘perform the journey leisurely and on foot; botanising and collecting insects and minerals and visiting every distinguished garden on his way’.10 Such a leisurely road trip would have been hard to pull off, given the distances involved. William McCulloch, who joined the Garden in March 1826, travelled more than 1,000 miles as he moved from garden to garden. Having served an apprenticeship of four years on the same estate in Louth where his father was land steward, William, aged eighteen, travelled to work in a plant enthusiast’s garden just outside Dublin for two years. From there he returned to Scotland to work under the famous curator of the Edinburgh Botanic Garden, Mr William McNab. After two years in Edinburgh, William McCulloch was promoted to foreman (so acquiring some management experience) under the head gardener, Mr Ross, at the Duke of Atholl’s estate at Dunkeld. He then completed his CV with a stint at one of the great London commercial nurseries, Messrs James Gray and Sons of Brompton Park, before applying to work for the Horticultural Society.

The Handwriting Book captures a surprising amount of mobility, given that the entries span a period that pre-dated the railway age. Although the first passenger service (the Stockton–Darlington Railway) opened in 1825, George Stephenson’s engine was still too feeble to manage the whole journey, and partway through wagons had to be hitched to horses to supplement the engine. It was not until 1830, when the Manchester–Liverpool line opened, that the first fully steam-powered service was in operation, and the initial boom in railway-building did not occur until 1836. The men whose notes appear in the Handwriting Book will most probably have relied on the network of public coaches. This network was extensive and services were frequent. For instance, in 1828 there were twelve coaches a day between Leicester and London alone. Nevertheless, distances of more than thirty miles involved overnight stays and were an expensive and (depending on the regions travelled through) fairly daunting undertaking. When William Craggs came to Chiswick in February 1825 from his father’s garden at Weare House near Exeter, the journey of 175 miles would have taken approximately twenty-one hours by stagecoach. Progress on the poorest roads was slow, and coaching inns were busy, noisy places where uninterrupted sleep was almost impossible. Some of our gardeners must have arrived at the gates of the Chiswick Garden motion-sick, muddy and exhausted.

All the entries end with the phrase ‘unmarried’. At this stage in their career, the gardeners could not afford to support a wife and family, and the Horticultural Society stipulated that all applicants should be single. Despite its aspirations to raise the standards of professional gardeners, the Society had no intention of tackling gardeners’ wages. This would hardly have gone down well with its Fellows, who would have had to foot higher wage bills. An article on ‘The Remuneration of Gardeners’ by I. P. Bunyard of Holloway in the Gardener’s Magazine refers to the Horticultural Society ‘very humanely’ giving its labourers fourteen shillings and its under-gardeners eighteen shillings a week.11 This compares with an unskilled farm labourer, who would earn around nine shillings a week; and it compared favourably with the Royal Gardens at Kew, which in 1838 was still only paying its gardeners twelve shillings a week. Nevertheless, fourteen shillings was not a wage that could support a wife and family, and the young gardeners depended on being able to have free board and lodging, although of a very basic fashion, in the shared dormitory known as a ‘bothy’. As Bunyard said in the same article, ‘A woe may be pronounced against the gardener who marries so prematurely; and it would be well to have written upon the gates of the Horticultural Society’s Garden at Chiswick, something like what Dante inscribes on the portal to hell “Lasciate ogni amor voi che entrate” (Abandon all love you who enter).’

However, many were prepared to make the sacrifice. Being knowledge- and skills-based, gardening undoubtedly offered opportunity for self-betterment for a bright, determined young man. Loudon believed that although young gardeners were paid much less than other skilled trades, people:

should not overlook the difference between the prospect of a journeyman carpenter and those of a journeyman gardener… he is perhaps as well off at twenty five as an industrious journeyman carpenter at forty five, because it would probably require that time before the latter could save sufficient money to enable him to become a master… The fact is that while other tradesmen require both skill and capital to assume the condition and reap the advantages of a master, the gardener requires skill only. Knowledge, therefore to the gardener, is money as well as knowledge.12

Chiswick offered unprecedented opportunities to add to that store of knowledge because it was the first place in the kingdom to see newly arrived plants from across the Empire. Even before Chiswick had been leased, the Society received plants from all over the world – including exotic fruits from Sir Stamford Raffles in Singapore, Chinese plants from John Reeves of the East India Company and seeds from Mexico via the foreign secretary George Canning. It was not long before the Horticultural Society decided to send its own representatives out to actively collect new plants.

The first was John Potts, a gardener who had worked for the Society at its small plot in Kensington. Beautiful paintings of Chinese garden plants sent to the Society by John Reeves were behind the decision to send Potts to China. His first shipment arrived in February 1822, including Paeonia lactiflora, Hoya angustifolia, several camellias and seeds of Primula sinensis. Unfortunately, poor Mr Potts returned in ill health and died shortly afterwards. The Society paid for his funeral and a gravestone in the churchyard at Chiswick. However, this unpromising start did not put off the Society or future plant collectors. Potts was followed by George Don (a distant relative of Monty Don), who joined Joseph Sabine’s brother Edward on a trip to Africa and the West Indies in late 1821; John Forbes, who collected plants in South America, Madagascar and Mozambique in 1822 and 1823; and John Damper Parks, who travelled to China in 1823–4. So by the time the young gardeners were starting to arrive at Chiswick, the Garden’s hothouses were already well stocked with exciting new plants.

In many ways the Society’s star collector of the 1820s was the young Scot, David Douglas, who travelled across North America collecting a stunning variety of plants, particularly American conifers. No other plant hunter had added so many new species to English gardens. It was the job of the Chiswick gardeners to unpack the precious parcels that arrived, marry them up with the plant lists provided by the plant collector and then (if the plants had managed to survive the journey) work out how to germinate the seeds or keep the specimens alive and propagate from them. Plants could come from any climate, any habitat, and the gardeners at Chiswick had to do their best to discern and then meet the particular needs of these new plants, often on the basis of very limited information. As a later Chiswick gardener reminisced, ‘Inhabitants of mountain, moor and fen, seaside and shady wood and plants from tropical and far lands, had all to be cared for, and the best soil, situation or treatments devised that would coax them to grow amidst the smoke and greasy fogs of an ever encroaching Greater London.’13 This was no easy task, but the opportunity to be the first European gardeners to see and grow these fabulous new plants must have been tremendously exciting.

And it was not just the plants; the Society was also constantly seeking to test the latest technology and techniques, and it invested in a range of different glasshouses and heating systems. The Horticultural Society was at the heart of the debate as to which was the most efficient and effective design and construction, and invested in a number of glasshouses and glazed pits (a glass roof over a recess in the ground) heated by a variety of different means, from braziers to pits filled with dung or other rotting matter. By 1830 there were more than 450 feet (137 metres) of glazed pits in the Garden, and some 400 feet (122 metres) of hothouses. In every aspect, the Chiswick Garden was designed to allow the Society to conduct and report on experiments to advance horticulture as a science. The men who trained there were able to participate, observe and learn from these experiments, which included experiments on hardiness (leading plants through successively cooler sections of the greenhouse, and trying them outdoors in different situations) and experiments to force plants to flower or fruit out of season, using different heating apparatus.

In the six years covered by the entries in the Handwriting Book, 105 young men were given an opportunity to work and learn in a unique garden and to pick up valuable skills and insights. What they did with that opportunity is the subject of the rest of this book.

CHAPTER ONE

‘The beau ideal’:The Horticultural Elite

Joseph Paxton admitted 13 November 1823 upon recommendation of Jos. Sabine Esq.

John Collinson admitted 21 Mar 1825 upon the recommendation of Mr Jos. Thompson

John Jennings admitted 1 February 1828 upon the recommendation of Joseph Sabine Esq.

John Lamb admitted 1 February 1828 upon the recommendation of Richard Arkwright Esq.

Donald McKay admitted 5 February 1828 upon the recommendation of Sir G. S. McKenzie Bt

Thomas Lamb admitted 20 June 1828 upon the recommendation of Richard Arkwright Esq.

ONE MAN ABOVE ALL TOOK ADVANTAGE OF THE opportunities that the Garden offered. That man was Joseph Paxton, unquestionably the most significant figure in British horticulture in the nineteenth century. He spent just over two years at Chiswick, and those years were enormously important to his success. In Joseph Paxton’s case, all the rags-to-riches clichés are true. He was born in Milton Bryant (now more commonly spelt Bryan), part of the Duke of Bedford’s Woburn estate. In his entry in the Handwriting Book, Joseph Paxton described his father as a ‘farmer’. However, there is no mention of his father’s name on any rent books for the Duke of Bedford’s estate and no mention of him in any of the land-tax records for the area, so it seems unlikely he was a landowner or even a tenant farmer. If his father was a simple agricultural labourer, then Joseph Paxton will have had a very basic education, particularly as his father died when Joseph was just seven. It is likely that Joseph’s older brothers helped support the family, and Joseph will have enjoyed basic schooling at a free school set up at Woburn by the first Duke of Bedford. It is clear that the ambitious young man felt it necessary to creatively enhance the part of his CV covering his schooling, in order to get into Chiswick. In his entry he gives his date of birth as 1801, when in fact parish records show that he was born in 1803. By this simple expedient he managed to suggest that he was at school for two years longer than he actually could have been, saying ‘at the age of fifteen my attention was turned to gardening’,1 when in fact he was probably working as a garden boy from the age of just thirteen.

There is another important anomaly in Paxton’s entry. The Handwriting Book says he was received into the garden on 13 November 1823, upon the recommendation of Joseph Sabine. Appointments were also recorded in the Garden Committee Minutes and when Paxton’s appointment appears a full five months later, the minutes record, ‘It is ordered upon the recommendation of the Secretary that Joseph Paxton, a person desirous of becoming a labourer upon the establishment be permitted to be so employed, his having previously been a Gardener notwithstanding.’2 As we have seen, the scheme to admit young men to train and develop at the Garden was designed for those who had not yet progressed too far in their careers. Yet in his entry in the Handwriting Book, Paxton admits that he had been employed as a head gardener to Sir Gregory Osborne Page Turner since late 1821. Why did Paxton leave a position of responsibility and status as a gentleman’s gardener, to take up the lower-paid and lower-status position of ‘labourer under the Ornamental Gardener’ at Chiswick? And why did the Horticultural Society agree to this?

It appears to have been a mixture of push and pull factors. The push factor was that by early 1823 Paxton’s employer, Sir Gregory Osborne Page Turner, was showing signs of insanity. Eventually his condition worsened and by 1824 he was declared bankrupt with liabilities of more than £100,000. Paxton may well have seen the signs and decided in 1823 that it was time to move on. Moreover, he was nothing if not ambitious. He must have understood that the opportunity to develop new skills and shine was much greater at Chiswick, the epicentre of cutting-edge horticulture, than it would have been in a relatively modest garden in Bedfordshire, with a mentally and financially unstable employer. We have no way of knowing exactly which strings Paxton pulled to get the Horticultural Society to overlook its own rules and let him in. Perhaps William Griffin, head gardener at Woodhall Park in Hertfordshire where Paxton trained for three years before coming to Chiswick, put in a word on Paxton’s behalf. Griffin, an expert on cultivating pineapples, was one of a number of professional gardeners and nurserymen who, thanks to their knowledge and expertise, were admitted to the membership of the Horticultural Society.

Once in the Chiswick Garden, Paxton’s prior experience appears to have allowed him to progress rapidly up the ladder. In November 1824, just under a year after he entered Chiswick, the Garden Committee Minutes record his promotion to Under-Gardener in the Arboretum.

Paxton’s efforts to bend the rules to get into Chiswick paid off in a much bigger way than simply quick promotion. Everyone working in the Garden will have been aware of its landlord and next-door neighbour, the Duke of Devonshire. The Society’s Chiswick Garden lay next door to the duke’s impressive gardens of Chiswick Park. The story goes that in 1826 the thirty-six-year-old George Spencer Cavendish met Joseph Paxton (then aged twenty-three) as the duke let himself into the Society’s Garden through the private door that he had insisted was constructed in the wall separating it from the grounds of Chiswick House. The unmarried duke was partially deaf and, despite his enormous wealth and social standing, was a shy and rather nervous man. In the young Joseph Paxton he met someone with a confidence and self-possession that he himself lacked. It seems that Paxton had the same knack possessed by an earlier giant of British horticulture, Capability Brown, of being able to speak affably and confidently with people from all stations of life, from garden labourers to dukes. Specifically, in the case of the Duke of Devonshire, Paxton also had the sensitivity to speak slowly and clearly, so that the deaf duke could hear him.

Over the past two years Paxton had worked his way through the different departments and had now been promoted to oversee the Arboretum, one of the most prestigious parts of the Garden. An arboretum was a collection of rare and beautiful trees and by the 1820s owning a fine arboretum was, for the landed aristocracy, a highly desirable status symbol. The Horticultural Society invested a lot of time and effort in ensuring that its tree collection was one of the finest in the country. The trees were arranged in ‘clumps’ surrounded by turf and ornamental plants, with a long canal running up the centre. Loudon heavily criticized the layout; it was too flat to be picturesque or aesthetically pleasing, and too erratically laid out to be systematic or scientifically informative. Whatever the arboretum’s design faults, Paxton was nevertheless in charge of a collection of rare and valuable trees. He was able to answer the duke’s questions with authoritative confidence and, in all probability, an enthusiasm that matched the duke’s own growing fascination with the business of gardening on a grand scale. Since coming into his inheritance of estates in excess of 200,000 acres (81,000 hectares) in 1811, the duke had indulged in a spending spree on his collection of houses and gardens and now needed someone to take charge of the vast project to remodel Chats-worth in Derbyshire. The estate was already a building site, with the fashionable architect Jeffry Wyatt undertaking an ambitious remodelling of the house and pleasure grounds. The duke had already begun a massive tree-planting programme, covering an area of over 550 acres (223 hectares), more than sixty times the size of the Arboretum at Chiswick. Even if news of this redevelopment had not travelled, as it surely must have done in the horticultural world, Paxton needed only to poke his head into the duke’s garden next door at Chiswick to see the resources to be enjoyed by a gardener lucky enough to work for him. In 1813 the duke had commissioned a 300-foot (91-metre) long conservatory to house the newly fashionable camellias from China.

In March 1826 the Duke of Devonshire offered Paxton the position of Superintendent of the Gardens at Chatsworth. This made him head gardener at one of the grandest estates in England, and an employee of one of the richest and most indulgent employers in the land. Indeed, the duke was so wealthy that he complained of having too many houses; when he went to his Irish property in Lismore in 1844, it was only his second visit in twenty-two years. As well as Chatsworth and Chiswick, he owned Burlington House and Devonshire House (two enormous mansions in Mayfair). He also owned large sections of the West End of London, as well as coal mines in Derbyshire. With the backing of such a rich patron, Paxton knew he would be able to take the things he had seen and learnt at Chiswick and try them on a much bigger scale.

After leaving Chiswick, he transformed Chatsworth at an amazing rate – improving the glasshouses, designing new buildings and waterworks and creating an enormous arboretum. With high-profile coups such as the Great Stove (then the largest greenhouse in Europe) and the colossal Emperor Fountain, it was not long before Joseph Paxton was in demand to work for other clients by contract. In the 1840s he began to lay out cemeteries and municipal parks. He branched out into publishing, becoming editor of The Horticultural Register in 1831 and Paxton’s Magazine of Botany in 1834. He collaborated with John Lindley on the Pocket Botanical Dictionary (1840), Paxton’s Flower Garden (1850) and The Gardeners’ Chronicle, the weekly magazine that was to take on the mantle of the Gardener’s Magazine as the essential newspaper of the horticultural world. Paxton reached the peak of his celebrity with his design for the world-famous Crystal Palace, the home of the Great Exhibition of 1851, an achievement that resulted in a knighthood. As if all this were not enough, he oversaw the provision of accommodation for troops during the Crimean War, was elected to the House of Commons as a Liberal MP and was heavily involved in a number of railway schemes. By the time of his death in 1865, Sir Joseph Paxton had transcended the world of gardening and was a national figure.

The problem was that Joseph Paxton’s success was so extraordinary, so singular, it only served to overshadow all the other men who had also trained at Chiswick. However, he was far from the only success story to come out of this remarkable garden. During the 1820s the Horticultural Society’s aim to recommend men to major positions across the country was realized to a considerable extent. Of the 105 men in the book, thirty-nine are recorded in the Garden Committee Minutes as leaving after being ‘recommended to positions’. This is probably an underestimate of the number who went on to work in senior positions in significant gardens. The Garden Committee Minutes cease in late 1829, so men recommended after that point are not recorded; and there were also several men who asked for ‘permission to leave’ because they themselves had obtained employment without waiting for a recommendation. Today, with the exception of TV gardeners, horticultural careers do not have the status they deserve; whilst he was prime minister, David Cameron famously dismissed gardening as an occupation for those who did not excel academically. It is landscape architects and garden designers, rather than gardeners, who take the plaudits and rewards. However, things were very different in the nineteenth century. Our gardeners were lucky enough to emerge from their training at Chiswick into a world that was much richer in opportunity for skilled professionals.