22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

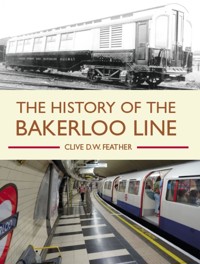

The Bakerloo is the dull brown line on London's iconic tube map. It doesn't have the multiple branches of the Northern or District Lines, the loops of the Piccadilly or the Central, or the puzzling shape of the non-circular Circle. But its nondescript appearance belies a history encompassing fraud in the boardroom and drama in the courtroom for a line first conceived by sports enthusiasts and finished by Chicago gangsters. With over 120 photographs, this book provides a history of its development from obtaining Parliamentary permission and raising finance through to geology and construction techniques. It details its operation including rolling stock, signalling, stations and signage from the beginning to the current day. The impact of the two World Wars is revealed and it remembers some of the accidents and tragedies that befell the line. Finally, the book describes its evolution up to the present day and beyond.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE HISTORY OF THE

BAKERLOO LINE

Escalators at St John’s Wood; the uplighters are part of the original design.

THE HISTORY OF THE

BAKERLOO LINE

CLIVE D.W. FEATHER

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Clive D.W. Feather 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 746 0

The right of Clive D.W. Feather to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and credit illustration and textual copyright holders. If you own the copyright to an image or quotation appearing in this book and have not been credited, please contact the publisher, who will be pleased to add a credit in any future edition.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1

Before the Bakerloo

Chapter 2

Building the Bakerloo

Chapter 3

The Wright Stuff

Chapter 4

Saved by Yerkes

Chapter 5

The Bakerloo Opens

Chapter 6

Extending the Line

Chapter 7

Improvements

Chapter 8

Stanmore

Chapter 9

World War II

Chapter 10

1950s, 60s and 70s

Chapter 11

Jubilee and Beyond

Chapter 12

Trains

Chapter 13

Signalling

Chapter 14

Safety and Danger

Chapter 15

Future Plans

Line Diagram

Appendix I – Dates

Appendix II – Proposed names

Appendix III – Station Locations and Layouts

Index

DEDICATION

To my wonderful wife Linda, who has put up with my interests for nearly forty years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to all those who have helped me with data or source material for this book, even if they didn’t know why I was asking. I am also grateful to the various people who provided me with photographs and who are named in the captions. I would particularly like to thank Mark Brader, who has done much fact and consistency checking in my other work over the years, some of which has fed into this book. Charles Dimmock corrected my understanding of the geology of London. Joe Brennan read my first draft and made comments. The Crowood Press first suggested I should write this book and steered me through the process of becoming an author. Finally, my late grandparents took me on the Underground many times as a child and sparked my lifelong interest in it.

A Bakerloo train sits in the reversing siding at Harrow & Wealdstone, the northernmost point of the Bakerloo today.

Introduction

‘Bakerloo? Um, that’s the brown one, isn’t it?’

The Bakerloo is indeed ‘the brown one’ on London’s iconic ‘Tube Map’. For the commuter or tourist looking at it, it is simple and boring. It does not have the multiple branches of the Northern or District Lines, the loops of the Piccadilly or the Central, or the puzzling shape of the non-circular Circle. Someone in their fifties might remember that it used to have another branch (someone in their nineties might even remember back to when it didn’t). Beyond that, what is there to say about the Bakerloo?

‘Bakerloo? Um, that’s the brown one, isn’t it?’

But peek beneath this bland surface and we find much more. This is a line that was conceived by sports enthusiasts, created amongst fraud in the boardroom and drama in the courtroom, finished by Chicago gangsters, and named not by businessmen but by a journalist. An underground railway threatened by weapons in the air in one war between political empires while at the same time being a weapon itself in another war, this time between commercial empires. A place where an enthusiast demonstrated a new way to control trains that, he hoped, would take over the entire country. And, looking ahead, a tool that could renovate a rundown part of London.

My own introduction to the Bakerloo was not as dramatic as this. As a child I would wonder why there were occasional Underground trains in the platforms at Watford Junction when we were waiting for the British Railways (BR) train to London at the start of an outing with my grandparents, or notice that we were using the Bakerloo to reach Stanmore before catching the 142 bus back to Watford at the end of the day. Back then, I was unaware of the rich history behind the Bakerloo Line; it was only as an adult that I became aware of it. But, now that we know it’s there, let’s wind the clock back more than a century and a half ….

A Note on Money and Measurements

Anyone younger than the author probably won’t remember that the UK used to use ‘pounds, shilling, and pence’ as money rather than the newfangled ‘decimal currency’ brought into use in 1971. Since this book will quote prices in the old money, here’s a quick guide to it.

There were twelve (old) pennies in a shilling and twenty shillings in a pound, making a shilling worth 5p and a penny worth just over 0.4p. A sum of four pennies would be written ‘4d’ (note the ‘d’ rather than ‘p’), three shillings would be ‘3s’ or ‘3/-’, and seven shillings and six pennies would be ‘7s 6d’ or ‘7/6’.

It is not always easy to compare prices from very different times, but, very roughly, the equivalents in 2019 money are:

Measurements have been given as they appear in the source material, together with the corresponding conversion: for example, rolling stock dimensions are noted in imperial, whereas distances drawn from LU data and OS maps are metric. Historical measurements are generally given in imperial, while more contemporary ones tend to be metric. Conversions are done to an appropriate precision.

Station Names

It is not always clear what is the ‘official’ name of a station and, indeed, some would claim that there is no such thing. It’s certainly not unusual for the same station to have signs with different variations on a name, such as including or excluding apostrophes, or using ‘&’ versus ‘and’; in the most extreme case, Piccadilly Circus was just ‘Piccadilly’ on some signs. In general, this book ignores such variability and sticks with what appears to be the most commonly used version.

Separately from this, several stations have changed names over the years. To avoid confusing the reader too much, present-day names are used throughout, with one exception: because two stations have held the name ‘Charing Cross’, this book uses ‘Trafalgar Square’ for the original Bakerloo station at that location (now called ‘Charing Cross’) and ‘Embankment’ for the station that originally and currently holds that name, but was called ‘Charing Cross’ for a while.

An entrance to Trafalgar Square station, showing its current name of Charing Cross.

Full details of name changes can be found in Appendix I.

Table 1 Abbreviations

Most abbreviations will be obvious from context or are explained when they first occur, but the following table gives the meanings of the more widespread ones.

BR

British Railways (

also called

British Rail)

BS&WR

Baker Street and Waterloo Railway

C&SLR

City and South London Railway

GCR

Great Central Railway (

became part of the LNER in 1923

)

GLC

Greater London Council

GWR

Great Western Railway

IRSE

Institution of Railway Signal Engineers

LER

London Electric Railways

LMSR

London Midland and Scottish Railway

LNER

London and North Eastern Railway

LNWR

London and North Western Railway (

became part of the LMSR in 1923

)

LPTB

London Passenger Transport Board

LSWR

London and South Western Railway

LTE

London Transport Executive

UERL

Underground Electric Railways Company of London

CHAPTER 1

Before the Bakerloo

The Bakerloo Line opened in 1906 after a stormy fourteen-year period of planning, construction and crisis that we will see in later chapters. But to understand its origins and the reasons for its construction, we must first look back another forty to fifty years, to London in the middle of the nineteenth century.

In 1860, London had a population of just over 3 million, making it the largest city in the world (second was Beijing, at around 2.6 million); it would double before the end of the century. It had been a port since Roman times and still made much of its money from shipping, though financial services – initially shipping insurance, but then banking and stockbroking – were also important. The centre of London was the City, based around the original Pool of London (the part of the Thames between the modern London and Tower Bridges) and the Bank of England, but it had spread perhaps 5km (3 miles) east and west and 3km (around 2 miles) north and south. In the east, the various dock systems based around the Isle of Dogs had taken over most of the shipping trade, but most of the rest of the growth was residential. Ten or fifteen years earlier the houses of the West End marked London’s edge, though by now some tendrils of growth had reached villages like Hammersmith and Putney. To the north, there was continual housing to Kilburn, Camden and Hackney, while to the south Putney, Clapham and Camberwell marked the edge of the built-up area.

There were three major east–west arteries through western London. The ‘New Road’ had been built in 1756–7 to allow troops to march around London rather than through it, yet by the turn of the century development was already past it in places. Today we know it variously as Marylebone Road, Euston Road, Pentonville Road, and City Road as it marches from Paddington to Moorgate. The second was Oxford Street and its continuation eastwards as Holborn and Cheapside into the City. This had started life as the Via Trinobantina, a Roman road from Hampshire to Essex, and became a major coaching route as well as the path taken by prisoners from Newgate Prison to execution on the gallows at Tyburn. Finally, the Strand and Fleet Street linked the City to government at Whitehall, Westminster and Buckingham Palace.

By 1860, the railways were firmly settled in London. On the south of the river, London Bridge and Waterloo were well established, Victoria was about to open, and the river crossings to Charing Cross, Blackfriars and Cannon Street were all due to open within the next decade. On the north side, Paddington, Euston, King’s Cross and Fenchurch Street were all present, but the Gothic monstrosity of St Pancras would not open until 1868. The lines that now serve Liverpool Street were present, but until 1874 they would terminate 600m (3/8 of a mile) further north at Bishopsgate, on the now-abandoned viaduct just south of the present Shoreditch High Street station. But, though river crossings to both the City and West End were allowed, Parliament had refused since 1846 to allow the railways from the north to cross the New Road.

So how did travellers from Bristol, Birmingham or York get to their destinations in the City or across to catch the boat trains for Dover? How did those from Southampton, Brighton or Canterbury get to offices in Whitehall or houses beside Hyde Park? The answer was the horse-drawn omnibus.

WHY IS IT A ‘BUS’?

‘Bus’ is a contraction of ‘omnibus’, but where does that come from? Well, the first bus service was introduced by the mathematician Blaise Pascal in 1662, but it was in 1825 that one Stanislaus Baudry started running a bus service in Nantes. Allegedly one terminus was outside the shop of a M Omnès, who had put up a sign ‘Omnes omnibus’ – Latin for ‘everything for everyone’. More likely, however, is the 1892 claim that Baudry changed the name from ‘White Ladies’ to ‘omnibus cars’ (‘cars for all’) after complaints that the earlier name made no sense.

London had been served by stage coaches for centuries, but the first bus service started in 1829, running along the New Road to be outside the boundaries of the hackney ‘cab’ monopoly. Unlike the coaches, the new buses did not have passengers sitting outside on the roof: they were all inside, protected from the weather. But in order to fit in the fourteen passengers that were typical of these services, they were crammed together ‘like so many peas in a pod’. Within five years, following changes to the laws and the taxes imposed on them, there were 376 licensed buses in London and passengers were back on the roof again as well as inside.

Today we think of buses as being a cheap form of transport for everyone, but these buses were far from that. Competing with short-distance stage coaches and cabs, the fare was normally 6d for any distance and, as a result, they were far too expensive for the working man. Rather, the typical passenger was the businessman, civil servant or clerk living in Marylebone or Kensington and working near to the Bank or Westminster. It may be interesting to observe that ‘manspreading’ is not a new phenomenon; on 30 January 1836 The Times wrote, ‘Sit with your limbs straight, and do not with your legs describe an angle of 45, thereby occupying the room of two persons.’

By the middle of the century, there were around 1,000 buses in competition with each other. Together with perhaps 3,000 cabs and a huge number of vans taking goods between the railway stations on the outskirts and the markets in the middle, the traffic was the kind of continual jam that we think is the fault of the car. Writers complained that it was impossible to cross the road without either being run over or kidnapped by a bus conductor desperate to find fares. One leading businessman stated that he always walked from London Bridge to Trafalgar Square because it was quicker: the cab journey took longer than the train from Brighton had and he could not predict, within a quarter of an hour, how long it would take.

Tiles on a now-closed entrance to Trafalgar Square present a map of the Oxford Road.

Typical London horse bus in about 1900.

Despite Parliament’s ban on railways entering the City, it was obvious that a railway would take much of the strain off the roads and two practical schemes appeared in the early 1850s. The first was the City Terminus Company, headed by Charles Pearson, the City Solicitor. This would involve a road from King’s Cross to Holborn with, underneath it, a tunnel containing eight railway tracks. These would connect immediately to the Great Northern at King’s Cross, but given that two of the tracks were to be broad gauge it was clear that they were intended to extend to Euston and Paddington. While the Corporation (the government of the City of London) was enthusiastic, the line would be expensive – the route involved buying and then knocking down hundreds or thousands of houses in slums – and nobody was offering the necessary funds.

The second scheme was the North Metropolitan Railway. This solved the cost problem by proposing to dig up the New Road from Paddington to King’s Cross, build a tunnel underneath it, then put the road back; no properties to buy reduced the cost dramatically. At King’s Cross the line would join the City Terminus line to Holborn. The North Metropolitan was approved by Parliament in 1853, but the City Terminus was not. After further struggles over the next five years, partly due to opposition in Parliament and elsewhere, and partly because of financial problems, the North Metropolitan took over some of the City Terminus Company’s route as far as Farringdon, though on a much smaller scale, and renamed itself the Metropolitan Railway. Between October 1859 and December 1862, various contractors proceeded to build a railway almost completely under the ground and, on Saturday, 10 January 1863, London’s – and the world’s – first underground line opened for service.

This is not the place for a history of the Metropolitan Railway – though we will meet it again later – or of what is now the Hammersmith & City Line, but its creation showed the world, and in particular those interested in getting around London, three things. First, the ban on railways south of the New Road had been breached and it was possible in principle to build other railways in central London. Second, these railways would be popular and could make money for their creators. But third, and by far the most important, it showed that a new railway did not have to carve an expensive swathe through existing houses, business and shops, but could be built underground with much less disruption using the ‘cut and cover’ system.

The success of the Metropolitan Railway meant that it was not long before people decided to try other routes. Anyone who studied the bus services would know that north-west London to Westminster and then the Elephant & Castle was popular: even in 1839 there were nine different bus companies with twenty-nine buses between them on the route. And so in 1865 the Waterloo and Whitehall Railway was born.

The Waterloo and Whitehall Railway was planned as a pneumatic railway: a line without locomotives. Instead, trains would be blown through a pipe; to quote the description in The Times: ‘The tunnel admits a full-sized omnibus carriage, which is impelled by a pressure of the atmosphere behind the vehicle, produced by lessening the density of the air in front.’ In other words, an impeller was used to suck out some of the air at one end of the tunnel and normal atmospheric pressure would push the train through the tunnel; on the return journey, the impeller was reversed to generate higher pressure to push the train back.

Pneumatic railways of this kind were not completely new: the idea had been invented by one George Medhurst in around 1810 and a modified version was patented by Thomas Rammell in 1860. Rammell and Josiah Clark established the Pneumatic Dispatch Company, which was to build three lines. A first demonstration tube was built above ground in Battersea in 1861 and used to carry goods and a few hardy volunteers – who would have had to lie down as the tube was only about 75cm (30in) in diameter – at speeds of up to 65km/h (40mph). This gained the interest of the Post Office and the company was engaged to build two lines to carry post and parcels. The first ran from Euston station to the North West District Office, about 500m (1/3 mile) away; the second from Euston to Holborn and thence to the General Post Office (now the BT Centre) near St Paul’s Cathedral, a total of about 3.2km (2 miles). The first line operated from 1863 to 1866 and the second from 1865 to 1874 (though only from Euston to Holborn until 1869).

Rammell believed that the system could be used to carry passengers and, on 27 August 1864, he opened a demonstration line in – or rather under – the grounds of the Crystal Palace in Sydenham (now Crystal Palace Park). The line ran from the Sydenham Avenue entrance, probably along the eastern edge of the park, to a point near the eastern end of the Lower Lake. It consisted of a brick ‘tunnel’ 550m (1,800ft) long; ‘tunnel’ is in quotes because a 1989 excavation showed that the base of the tube was only 1.5m (5ft) below ground level, so must have sat in a trench with the top half sticking out, possibly disguised with earth. The train consisted of a single carriage containing thirty-five seats, with a ring of bristles at one end to provide a nearly airtight seal to the tunnel. Despite the sharp curves and the 1 in 15 (6.7 per cent) gradient, far more than a conventional steam train could cope with, the impeller (driven by a modified steam locomotive) only needed to produce a pressure of 2½oz to the square inch (11hPa, or about 1 per cent of atmospheric pressure) to push the train through in about 50 seconds, an average speed of 40km/h (25mph). The demonstration line operated for about two months.

Returning to the Waterloo and Whitehall itself, the idea was to build a pneumatic tube between the two places across the Thames, making the journey much quicker than a bus or cab, which would have to divert via Waterloo Bridge or Westminster Bridge, or a walk over Hungerford Bridge (which cost ½d each way). The proposed route started with an open station at the Whitehall end of Great Scotland Yard, then followed the latter to the river at a point roughly where, today, Whitehall Place meets Whitehall Court (this being before the planned Victoria Embankment had been built). It then crossed the river before running under College Street (now underneath Jubilee Gardens) and Vine Street (destroyed to make way for the 1951 Festival of Britain and now under various buildings) to the edge of Waterloo Station, at a point that is now part of the erstwhile Eurostar platforms. The total length would have been about 950m (0.6 miles) (most sources quote the length as 1,200m [3/4 mile], but this is not consistent with the route given in the prospectus) and the steepest gradient on the line would be about 1 in 30 (3.3 per cent), significantly less than on the demonstration line. On land, the tunnel would have been cut-and-cover brick construction, while to cross the river it would use an iron tube 12ft 6in (3.81m) in diameter coated in concrete. A trench would be dredged across the river and four brick piers would be sunk into the bed down to the solid clay beneath, each with a chamber at the top. The five tube pieces, sealed at each end, would be lowered into place and inserted into these chambers; it is not clear how they would be fixed together, but possibly by divers. Once all joined up, the seals in the ends could be broken through to give a continuous tunnel. In effect, the result would be a bridge sitting in the riverbed, rather than a pipe sitting on it.

Hungerford footbridge – linking Whitehall to Waterloo – in 1859. JAMES ABBOTT MCNEIL WHISTLER

The six initial directors of the company included two directors of the London and South Western Railway (LSWR), which terminated at Waterloo station, and the chairman of the Metropolitan Railway. The former was no doubt attracted by the idea of a good connection to the north side of the river (unlike the other main railways south of the Thames, the LSWR never had a terminus on the north side), while the Metropolitan was probably interested in the technology: despite the usefulness of its line, there were a lot of complaints about the smoke and fug generated by steam engines in the long tunnels. The capital of the company was £135,000 and, as was usual at the time, only a proportion had to be paid up front to buy shares (20 per cent in this case), with the rest being demanded as construction costs required. Some press reports suggested that, if the line was successful, it would become the core of a route from Elephant & Castle to Tottenham Court Road.

The prospectus claimed that a train would run every 4 minutes from each terminus and that trains would alternate in direction. Even if there were two platforms at each end (unlike the demonstration line), so that one train could enter the tunnel as soon as the previous one exited, that would mean a travel time of under 2 minutes, so an average speed of about 31km/h (19mph) with a top speed in the Thames tunnel perhaps 50 per cent greater. Services would run from 07:00 to midnight daily. The company expected trains to carry an average of twenty-five passengers each; 80 per cent would pay 1d for a second-class seat, while the remaining 20 per cent would sit in first class at twice the price. This makes a very exact £23,268 per annum, which would be split 30 per cent for running costs, 12 per cent for interest on the loans taken out to help fund construction, and 58 per cent in dividends, meaning a very comfortable 10 per cent dividend on the shares. The shares would also pay 6 per cent interest – already a very good rate for the time – while the line was being constructed. The prospectus was proud to state that ‘its construction will not involve the demolition of a single dwelling-house’; this, of course, meant that no compensation costs would have to be paid to householders or landlords.

Rammell’s demonstration pneumatic train arriving at the Sydenham Avenue station. LONDON ILLUSTRATED NEWS COURTESY ROGER J MORGAN

The Waterloo and Whitehall’s Act of Parliament was passed in 1865 with little or no opposition and construction was started. However, the following May the financial house of Overend, Gurney and Co. collapsed following a drop in stock and bond prices. Overend, Gurney was a major player in the market, certainly bigger than its three biggest competitors combined and with deposits twice those of the Bank of England. The collapse triggered a major financial crisis in London – the ‘Panic of 1866’ – with the bank rate rising to a then unprecedented 9 per cent and then 10 per cent. The Bank of England had to be reconstituted as the ‘lender of last resort’ – a role it still holds today – and the panic and resulting recession is credited by some as being the cause of the 1867 Reform Act (which doubled the number of voters by adding many working-class men to the electorate). Meanwhile, the recession meant that it became hard to borrow money – money that the Waterloo and Whitehall needed to fund construction. By 1868, though it had done a fair amount of work, the company had just about given up the effort. A further blow was struck by the opening in January 1869 of what is now Waterloo East station, creating a rail service between Waterloo and Charing Cross. The line was officially abandoned in 1870 and the surplus machinery and materials were auctioned off in 1872. The company was eventually wound up in 1882. It is claimed (though there is no solid evidence) that part of the W&W’s tunnels is now in use by the National Liberal Club as its wine cellar. With this possible exception, all evidence of the line has gone, though part of the tunnels under Vine Street were discovered in the early 1960s when excavating foundations for the Shell Centre.

A piece of the Waterloo and Whitehall’s under-river tunnel during construction. SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN COURTESY JOSEPH BRENNAN

In 1881, there was a second attempt to build a railway from Waterloo to the north side of the Thames near Whitehall: the Charing Cross and Waterloo Electric Railway, launched by (among others) two directors of the Great Eastern Railway.

The Charing Cross and Waterloo was aiming at the same market as the Waterloo and Whitehall: people wanting to get across the Thames from Waterloo station to the general area of Trafalgar Square. For this reason, its design and route were very similar. It started at an open station at the edge of Waterloo station. The lines then descended into a cut-and-cover tunnel under Vine Street and then College Street to reach the Thames, descending at a 3 per cent (1 in 33) gradient all the way. On the north bank of the Thames it would then climb at 2.4 per cent (1 in 42) under Northumberland Avenue; this had been driven from Embankment to Trafalgar Square in 1874, replacing the former Northumberland House and its grounds. The terminus would be 20ft (6m) below ground level just before the junction with the square itself, opposite the Grand Hotel under construction at the time. The line would cross the Thames in two iron tubes in trenches, as with the W&W. However, the use of Northumberland Avenue meant that the river crossing would take a noticeable diagonal. The total length would be about 1km (5⁄8 mile).

The big difference from the Waterloo and Whitehall, however, was the form of traction. Pneumatic tubes were a dead duck, but it was no longer necessary to revert to steam. Dr Werner von Siemens had shown that it was practical to haul at least a small train using an electric locomotive powered from a fixed generator. In 1879, he built a demonstration line consisting of a loop 300m (330 yards) in length with a small locomotive pulling three carriages holding eighteen to twenty people each at about 12km/h (7½mph). It used a central third rail or, rather, a vertical iron plate, with the return through the running rails. In 1881, this was moved to Crystal Palace Park; at the same time, Siemens was building a 2.5km (1.6 miles) passenger line on the outskirts of Berlin and was proposing a 10km (6 miles) elevated line within the city, both electrified (but using the two running rails to carry power, like a model railway). Dr Siemens also pointed out that the electric motor in the locomotive could brake the train by becoming a generator, a technique still in common use today. In two years’ time, the first electric railway in the UK – Volk’s Electric Railway – would open in Brighton; it is still running today.

Volk’s Electric Railway on the Brighton shoreline; the first electric railway in the UK.

The promoters of the Charing Cross and Waterloo leapt on the idea of electric trains and gained Siemens Brothers as backers, with Dr Carl Wilhelm Siemens (a younger brother of Werner) as electrical engineer. Their prospectus pointed out the advantages of electric traction, with clean air and no smoke in the tunnels. The trains would be single lightweight self-propelled carriages with no locomotives.

The company’s initial Act of Parliament obtained Royal Assent on 18 August 1882, but the attempts to sell shares and so raise money only started in the following April. The capital of the company was £100,000; again, only 20 per cent had to be paid up front to buy shares and the rest would be demanded as construction costs required. This time it was made explicit that each demand would be no more than 20 per cent of the share price and would be made at least three months apart, allowing prospective buyers to plan their cash flow. The company could also borrow up to £33,000. Contractors had been found who would build the line for £80,000 and Siemens Brothers wanted £12,000 for the electrical equipment (the generator to supply power would be beside the Waterloo station).

The prospectus again described the expected service. The running time was 3½ minutes, making the average speed only about half that of the Waterloo and Whitehall, and there was no timetable: trains would ‘start as filled’ (presumably empty or part-empty trains would be sent back if there was more demand in one direction than the other, just as in rush-hour today). The company expected to carry 12,000 passengers per day, with one-third in first class paying 2d and the rest in second class paying 1d; these were the same prices as the W&W, but with more in the expensive seats. The company’s Act actually allowed for three classes at fares up to 6d, 4d and 3d but, presumably, it was decided that these higher rates would discourage too many potential passengers. If these targets could be met, the company would earn £24,333 per annum; Siemens Brothers would be paid £5,867 to provide and run the trains (they had a five-year contract that paid them £5,000 plus 20 per cent of any income over £20,000 each year), which, after deducting £4,000 in maintenance and management expenses, would mean a very impressive 14.5 per cent dividend for the shareholders. On the other hand, unlike the W&W, there was no offer of interest while the line was being built. In an attempt to justify these figures, the prospectus pointed out that there were 22,106 carriages and 93,274 pedestrians crossing the three bridges in the area each day, but failed to remind investors that the crossing was now free: the Metropolitan Board of Works had purchased Waterloo Bridge and the toll rights of Hungerford Bridge in 1878, abolishing the tolls.

Even before any significant work had started, the company was looking at extensions. A December 1882 Bill proposed extending from Waterloo via Blackfriars to the Royal Exchange, roughly following the route of today’s Waterloo & City Line and trebling the length of the line. An extra £336,000 would be required for this. This idea was dropped in May 1883. Instead, Siemens Brothers were promoting the London Central Electric Railway, which would have extended the Charing Cross and Waterloo from Trafalgar Square north to meet Oxford Street near Holborn and then eastwards along the route of the present Central Line to the Post Office (present-day St Paul’s). Parliament rejected this as too speculative, wanting to see if the CC&WER worked first. But the latter was in trouble. Attempts to sell its shares had not gone well and it could not afford to undertake any construction (apparently only about 20m [66ft] of tunnel was ever built). Then, in December 1883, Dr Siemens died, removing one of the driving forces of the line. In November 1884, the company brought two separate Bills to Parliament. One would allow the line to be extended along Cockspur Street to ‘85 yards west of the statue of Charles I’ (in other words, to the south-west corner of Trafalgar Square) and would extend the time allowed for construction. The other, however, would allow the entire railway to be abandoned. It was this latter that received Royal Assent on 16 July 1885, sounding the death knell for the line.

Hungerford Railway Bridge in 1890. CAMILLE PISSARRO

One more railway proposal should be mentioned: the King’s Cross, Charing Cross and Waterloo Subway, which would have been much more like a modern tube line than the previous ones. This 1885 proposal followed the route of the CC&WER from Waterloo to Northumberland Avenue, though the station would be at the junction with Northumberland Street. From there, it would run along the east side of Trafalgar Square, then under St Martin’s Street, Long Acre, Great Queen Street, Southampton Row, Theobolds Road and Gray’s Inn Road to King’s Cross, a total of 2 miles 13.8 chains (3.5km). The promoters withdrew the proposal in May of the same year and it was not raised again.

PARLIAMENTARY PROCESS

A railway line can’t just be built without anyone’s permission unless the entire route is on, or under, land owned by or leased to the company, or land where the owner has given permission (a ‘wayleave’ – literally ‘leave to create a way [through]’). Clearly, it would only take one recalcitrant or greedy landowner to block the line or make it too expensive to build. So up until around the start of the present millennium, railway companies were authorized by a Private Act of Parliament. This Act could grant powers to do things such as to build on or under public lands, to block or reroute roads (either temporarily or permanently), and to open up the route via compulsory purchase, lease or wayleave rights at a fair price, usually determined by an impartial party.

Gaining an Act was far from trivial or cheap. Before the process could start, the promoters needed to put together detailed plans showing exactly where the line would go and what land would be needed for both the line and things like station buildings, goods yards and engine sheds (including a small margin for error). These plans would be accompanied by the Book of Reference, which named the landowner for each piece of land or building affected by the railway. All this paperwork had to conform to Standing Orders issued by Parliament.

Most importantly of all, for a new railway company the promoters needed to determine how much it would cost to build the railway and, therefore, how much money the company would need to raise. This was important because, once the company had its Act, the line could normally only be funded in two ways: either the company sold shares in itself to obtain the money it needed, or it could borrow from banks, other companies or individuals. In general, borrowing was limited to 25 per cent of the total.

Once it was ready, the company had to wait for a narrow window of time, usually in November or December, to deposit the text of its Bill, the plans, the Book of Reference and other necessary documents at the offices of Parliament. Furthermore, the promoters had to deposit 5 per cent of the cost of the new line with approved bankers (this could be cash or other securities). So, for example, if they decided that the total cost (including an allowance for unforeseen circumstances) would be £200,000, the Bill would set the capital of the new company at £150,000 of shares with borrowing rights of £50,000, while the promoters would have to deposit £10,000 with their paperwork. This deposit would only be returned when the railway was completed and opened, if the Bill failed to get through Parliament, or if a later Act allowed the line to be abandoned.