Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

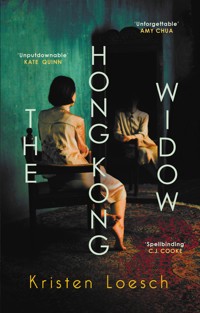

'A stunning, addictive, genre-bending book that will sink its claws into you from the very first page' C.J. Cooke 1953. Mei's 'gift' of speaking to ghosts is one that she has endeavoured to bury while fighting to survive as a refugee in post-war, post-revolution Hong Kong. When former silent film star Holly Zhang invites Mei to the infamous Maidenhair House, the startling summons revives her link to the man who destroyed her life. During six s ances over six nights, each night a medium will be asked to leave until only one remains as the recipient of a staggering reward, but the only prize Mei wants is revenge. Years later, that shocking night in the labyrinthine mansion has become an urban legend, dismissed by the police at the time as a collective hallucination. Mei must uncover the truth of what really happened and see if the ghosts she has carried can finally be laid to rest. 'The Hong Kong Widow is a tour de force: tense, emotional, poetic, and utterly unputdownable' Kate Quinn

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 468

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

123

THE HONG KONG WIDOW

Kristen Loesch

4For Gong and Po56

Contents

Prologue

Susanna has her lips pursed, like she is sucking on sweetroot. I am telling her what it is like to be attacked by an unknown assailant in a darkened room. How it feels to wake up half a day later, your head throbbing, one eye swollen shut, lying flat on a tatami, the straw beneath you turned sticky, your arms stiff at your sides, your fingers bent like you’re holding a ball. One of those small spleeny organs that nobody knows about until they lose it – you’ve lost it.

You know it’s normal not to be able to recall anything of the attack itself. Normal if you can’t picture your attacker; normal if everything is hazy in your head.

The problem is that it isn’t.

Imagine that you remember the events of your attack perfectly – but you remember it all the wrong way around. In your memory you see yourself on the ground, bleeding badly; in your memory you go closer, bending over your own form, your own face.

In your memory, you are not the victim. You are the attacker. 8

‘Uh-huh,’ Susanna says, jotting something down on her handheld electronic screen.

Susanna Thornton is an award-winning author of narrative nonfiction, known for her interest in murky historical mysteries, particularly crimes. Why else has she sat me down like this, if not for a story such as this one? Her initial request for an interview was shocking; her voice on the phone was clipped and stern and gave nothing away. But she can’t just want the usual bland impressions of the decades I have lived through, the Japanese occupation of Shanghai, the Pacific War, the Chinese Communist Revolution.

I want her to want more.

I want to see her innate curiosity piqued. I want to hear her laugh openly at me. I want her to tell me that it’s impossible, what I have just said, all while her mind spins with possibilities.

But it seems she has little concern for the darkened rooms of my life.

‘That happened back in Shanghai?’ says Susanna, but it’s not quite a question and she doesn’t wait for an answer. ‘I don’t want to waste your time – I’m here to ask you about Hong Kong. About Maidenhair House.’

For a moment it feels as if I am waking up half a day later, all over again.

‘I’m sorry. I must have misheard you,’ I say.

‘Maidenhair House,’ repeats Susanna, whose voice is very clear, whose voice regularly carries over the heads of hundreds of people. ‘About the late-summer night in 1953 that’s turned into an urban legend. About the alleged 9massacre. About how, when the police were called to the scene, they couldn’t find a trace of it – and later called it a collective hallucination.’

‘Then what is left to say?’ I ask, but perhaps she can hear my heart beating slightly faster, just by my voice.

‘It’s been confirmed that several young women went up to the house that night and were never seen again,’ says Susanna. ‘Women who were refugees of the Revolution. Women with no family or friends. Women that nobody would have missed. I’ve spoken to some Canadian urban explorers who spent a night at Maidenhair about fifteen years back now,’ she adds, with a hint of satisfaction, ‘and I got one of them to admit that there was indeed blood. When they went over it with luminol, they found blood everywhere. Walls. Floors. Rugs.’

She says this like it is a revelation, blood beneath your feet.

Maybe in this country it is.

But in the place I come from, the dirt is always red, if you dig deep enough.

The balloon-whistle of the espresso maker sounds from another room, but Susanna doesn’t budge. She thinks the silence will force me to speak. She sweeps her long mat of hair behind her shoulders. I have thought of other things to talk about by now: perhaps about the time my mother forced me to sell my own hair to a visitor to our village who was trying to add to his collection of female braids; how much I wanted to refuse; how if I were not so tragically proud, I might have begged. But we needed the money and in the end Ma got her way. She cut it just above the jaw.

‘I intend to solve it,’ says Susanna. 10

She can get my hair back for me?

Even if by now it is scattered across China like ashes?

‘I’m going to uncover the truth about that night,’ she insists. I am not sure this is an interview so much as it is a sounding board, because clearly the story she wants to tell is already formed in her head. I can see it shining in her eyes. ‘I’ll do it with your help or without it, Mama, but I’m going to find out what happened at Maidenhair House. And I’m going to find out why you got away.’

PART ONE

1

Seattle, Washington, 2015

Susanna’s dining table is long, meant for more people than just me and her. At every place setting there is a plate and enough slim silver cutlery that I could make a traditional Chinese cutting of the tablecloth; it is an eerie scene. Once there were three eating at this table every day, of course: Susanna; Peter, her first husband; and Liana, my granddaughter. Then came the divorce; then there were two. Then Susanna married Dean, and there were three again. Then Liana left for college. Then there were two again. And now Dean is gone.

I am here tonight, but my daughter acts like she is alone.

Susanna sits across from me, reading on her phone, her eyes moving visibly beneath the lids. All the food on the table has just been taken out of the fridge.

I take a sip of my tea. It is hard and gritty.

‘Something wrong, Ma?’ she asks.

‘It’s so cold in here, that’s all. Did you take this whole house out of the fridge?’ 14

A short sigh. ‘You didn’t have to stay for dinner.’

How could I go, after the conversation we have had?

I had not thought about Maidenhair House in several decades, but now the memory burns brighter than the light overhead. Susanna, naturally, does not see the effect her reminder has had on me; she thinks Maidenhair is like any other murder mystery she has ever encountered, gone rancid with time. I wonder how she learned that I was there that night, but it surely involves more devices, more squinting, more poorly-lit rooms.

I imagine a list of women’s names, one after another. I imagine Susanna struggling to make sense of it, and in the end, believing what she sees.

The greatest surprise is not her discovery of my presence, nor her self-proclaimed investigation.

The greatest surprise is that my daughter has got out of bed.

She has hardly left the house since Dean died, three months ago.

‘Yes, I was at Maidenhair,’ I say, and her eyes widen. ‘But I have never spoken of that night to anyone. Not because I have something to hide, but because I have had no desire to turn over the past like the dirt of a grave.’

It has the effect on her that I hoped for, and simultaneously dreaded. Susanna sets down her phone and diverts her full attention to me.

‘But you’re willing to talk about it now?’ she says.

I notice that she hasn’t picked up anything to eat with; she has become as skinny as a bamboo stake. ‘If you do something for me in exchange.’

‘What is it?’ 15

‘I want you to find out why I remember being attacked, so many years ago, from the perspective of my attacker.’

‘The thing you described earlier, you mean?’

‘That is my condition.’

‘Forgive my bluntness, Ma,’ she says wearily, ‘but I’d say it was a trick of your imagination. Your brain trying to protect itself from whatever happened. But if you want me to find out who attacked you, I suppose we can try. When was it? Not when you were growing up? Because 1930s Shanghai, we’re talking Japanese soldiers, gangsters, drug dealers, criminal overlords,’ she says, like I might not know, like I wasn’t there. ‘It might be difficult to—’

‘I didn’t say who. I said why.’

‘Well, it’ll have to wait either way. I’ve booked a flight to Hong Kong, for research.’

Susanna sucks air in through her nose, as if to prepare for my objections. I do have objections. I want to say: on the subject of somebody’s brain trying to protect itself from what has happened, why are you suddenly so drawn to a story like Maidenhair? To old deaths; to open-ended deaths? You say you want answers; I think you do not want answers. You want to hunt. You want to chase. You want to run. You want to spend your time on people who cannot die in your arms, because they are already dead.

But at least she has got out of bed.

Perhaps this is the start of a new stage of grief. First, she could not move at all. And now she cannot stay still.

For the rest of the meal, Susanna keeps her head turned so that her hair hangs over her face, blocks my view of 16her. Her hair should be streaked with white, but it is dyed dark. Dollhouse hair. To go with the dollhouse food and the dollhouse house. All she is missing, now, is the dollhouse husband. I should tell her about the day I ran into my own future husband, her future father, in a bustling marketplace in Tsim Sha Tsui. I was idling near the hundred-year-egg stall when a young man approached me. He had to stoop to speak to me. I had missed breakfast that morning, and I was hungry; over the rumbling of my stomach I heard him apologise for disturbing me. He was irresponsibly handsome, handsome enough that I forgot one hunger, and remembered another. He held out a hand, turned upward. I think you’ve dropped this—

I grabbed my white peony flower hairpin out of his palm.

This young man asked me if I wanted a hundred-year-egg.

By then I was corroding like iron, from the wanting of things.

‘You have my condition,’ I say to my daughter. ‘Let me know what you decide.’

Susanna does not answer.

Hundred-year-egg has a tough, almost impenetrable crust, but on the inside, it is soft. It is weeping.

The tapestry of clouds in the distance has lifted, revealing the outline of the Cascades. Susanna has surprisingly agreed to drive me home; bent over the steering wheel, she rubs at a red splotch of skin on her wrist. The car’s touch screen display glowers rudely at us. I have no idea why the navigation is turned on. Susanna should not need directions to my home, at least not before nightfall. I wonder if it is always nightfall now, for my daughter. 17

A phone call flashes on the screen: Liana. Susanna doesn’t pick up.

‘Is Liana still having trouble sleeping?’ I ask, after the ringing dies. ‘The insomnia, the nightmares?’

‘So Peter says,’ she replies. ‘Now apparently she’s …’

‘She’s what?’

‘Seeing things,’ says Susanna, in a breath.

‘What does my granddaughter see?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Perhaps if you took her calls you would know.’

‘Peter says she isn’t liking grad school. He doesn’t think we should make a big deal out of it.’

‘Have you spoken directly to him? To either of them? Or you only communicate through those bubble messages that make my temples ache?’

Susanna is too busy rubbing the red spot raw to respond. Liana came up from LA shortly before Dean’s death, and mother and daughter have not seen each other in person since. Liana didn’t visit for the funeral because there wasn’t one; Susanna arranged a quick cremation before making a permanent burrow of her bedcovers. These past few months she has seen nobody but me, and only because I have a key to her house. Only because I refuse to go unseen.

I have been so gentle with her. I have hovered over her like a cloud.

What good has it done?

Now she is finally leaving her house, but going to Hong Kong instead of LA. Now she will finally raise her head again, but only as high as her touch screen.

‘You really shouldn’t be living alone any more, you 18know, Ma,’ Susanna says, opting to go on the offensive. ‘Weren’t we talking once about getting you a place at—’

‘At least I do not live in your house. It is a cube.’

She flinches at my tone.

‘There are memories like nails sticking out of the walls in that place, Susanna. No wonder you are so pallid and sick-looking. You are bleeding out. You should sell it.’

‘All this was different for you, alright?’ she says, her hands rigid on the wheel. ‘You didn’t love Dad the way I loved—’

She can’t finish, but her voice is bitterly triumphant. As if to say Admit you didn’t love him. Admit that you don’t know what it’s like for me.

‘It depends on what you mean by love,’ I say. ‘I cherished him. I miss him. But I did not wring myself out like a cloth for him, and he would have not wanted it. You have to understand that by the time I met your father, I had no desire for something so fragile that it would fall to dust in my hands. I had been swimming, gasping for air, for so long. What I had with Dad was a boat. We built it together, knowing it would carry us however far we needed to go.’

‘Well, I didn’t want a boat. I wanted something else,’ she says hotly, ‘and I got it.’

‘If you had a boat right now, maybe you wouldn’t be so stuck in place.’

‘You and boats. Sometimes you can’t just – can’t just move forward like that, Mama! That easily! That quickly! I’m not ready to sell the house. I’m just not. I—’

‘Have you decided whether to accept my condition?’

Silence again, but this time it is more like static. It has 19begun to rain. Susanna turns on the wipers, which creak moodily across the windshield. ‘I want to take care of Maidenhair first,’ she says, ‘and then – yes. I can look into your – attack.’

She scratches again at her wrist, and this time she draws blood.

It was September 1953, the last time I laid eyes on Maidenhair House.

But the real story begins many years before that.

I gaze at my daughter, the sweep of her jaw, the craters of her eyes, the frayed shawl of her hair, the way her sweater is buttoned all the way up the neck, nearly a noose.

‘I’m going with you to Hong Kong,’ I say, and she jolts back in surprise.

‘Are you kidding?’ she exclaims.

‘Why shouldn’t I go? I have been acquiring air miles for decades. It would be upsetting to die without having used them. I have achieved special status with the airline by now; I can get excellent upgrades.’ Susanna is still protesting, but we have reached our destination, the small bungalow I shared with my late husband for almost half a century. I want to tell my daughter, do not go back to your cube house. Do not live in a box. Boxes are what people are buried in. ‘There is even an extra fast line, for going through immigration,’ I tell her. ‘That is the most important thing.’

‘That’s the important thing? You’re eighty-five years old, Ma! Who cares about extra fast lines in immigration? You can’t just—’ 20

Someone who is eighty-five, that’s who. Someone who could fall down dead at any moment, anywhere, right where she is standing. Someone who lived too long on the line, between one country and another; who refuses to die in the in-between place.

2

Kowloon, Hong Kong, September 1953

The final customer of the day is an old lady with flaming white hair and a gold-capped cane, like a sceptre. A lavish green cloak strains from her shoulders to her feet, sweeping the aisles clean as she browses. She chatters low, as if to herself, a sly stream of gossip about this shoe-shiner’s love affairs and that washwoman’s slug of a son-in-law. She does not appear to require any assistance, so Mei begins to redress the window display: the brass Buddhas and Jingdezhen porcelain plates must be swapped out for burnished chicken-blood and field-yellow stone. Away come the small model ships and the mother-of-pearl Mahjong sets, and in go the festive Mid-Autumn lanterns.

Mrs Volkova often says that Mei should hang up some of her traditional paper cuttings. Perhaps Mei’s signature design, the unfurled peony flower, because aren’t such cuttings meant for windows? Isn’t light meant to stream through the slits in the paper; the negative space? 22

But Mei keeps her designs tacked to the walls in the back. She believes that the sun would only spoil them.

The evening has grown stale and silent. Volkov’s Curio Shop should be long closed by now, but the visitor will not leave. You need the patience of the goddess Tin Hau not to snap like a pencil tip, putting up with people like this; or else you need to be in customer service. Mei sands her teeth together, swipes the sweat from her forehead. It might still be worth it. She senses that this woman could afford to buy this whole building, squat and derelict and dirty as it is, and the wealthy do not often find their way to this part of Kowloon.

The lady says, ‘You’ve heard of George Maidenhair, I presume?’

The red diamond character banners slip right through Mei’s hands.

Immediately, she gathers them back up. There is nowhere to faint in a display like this, except face-first on the Buddhas. After speaking so long without a stop, now the woman is awaiting a reply, but how can Mei respond? Yes, Auntie, I have heard of George Maidenhair. I have spoken his name; I have screamed it into my hands. Yes, Auntie, and he would have heard of me. But look how I am many years, and hundreds of miles, and one entire country, away from all that.

Look how well I can string these banners, without my hands even shaking—

The old woman repeats the four syllables of George’s full name. She says that he ran an infamous business empire back in Shanghai. That he all but owned the Paris of the 23East. That he married the former silent-film actress Holly Zhang. Surely, Mei knows of him, because even the fish-slingers down at Lei Yue Mun know of George, even the rickshaw drivers so skinny their shirts get sucked into their stomachs, even the addicts in their dens and divans lying as still as effigies, even the Triad thugs who have never left the blackened courtyards of Kowloon Walled City – they all know him.

But everybody says they know everybody, in a city nearly built on top of itself, like Hong Kong.

As she listens, Mei turns the character fú upside down, so that luck pours out for the Mid-Autumn Festival. It feels like she might be standing on her head. Heat is rushing to her cheeks; they must be as red as the banners.

For a moment she wants to bring this whole window display crashing down.

For a moment she wants to see everything she has spent so long putting up ripped to shreds.

George Maidenhair: taipan and business mogul. George Maidenhair: American-born; Oxford-educated; hell-bound. George Maidenhair, with a laugh as hearty as Tientsin cabbage soup, without any soul. George Maidenhair, whom they called the Golden Man back in Shanghai, some said for his good-luck, ferry-light, tossed-yolk yellow hair, others said for his money, but Mei would say because he was a false god. George Maidenhair, who cracked Mei’s entire life down the middle, the way she could one of these porcelain plates, forever beyond repair.

When it comes to George, Mei has just as much to say as this woman. She could be the one talking without needing answers.

24The woman approaches the display. As she draws near to Mei, her cloak flaps fishlike around her. Up close, it turns out, the old woman is not that old at all. Up close the blazing white hair is a wig. The gold-tipped cane might be a weapon. She says that George Maidenhair bought the old Hall mansion on Victoria Peak a few years back and renamed it Maidenhair House. She says, smiling now, as if it’s a joke, that the refugees of the Revolution who are pouring into Hong Kong these days no longer need a family name because there is nobody left to share it with, and then there are people like George, who slather their names onto everything.

Mei herself fled the Revolution.

But that is not all she fled.

When Mei left Shanghai in 1948, at eighteen years old, it was with the absolute certainty that she and George Maidenhair could never again live in the same city. They could not coexist. One of them would have to go, or one of them would have to die. Mei feels suddenly cornered, with the display behind her, this woman in front of her, George all around her. She moves to step away from the window, but does not quite manage. Her composure is slipping. Her tongue is swelling to fill her whole mouth.

The visitor seems not to notice.

‘Holly Zhang – George’s wife – is fascinated by the occult,’ says the woman. ‘You may have heard the stories about the old Hall House?’

Say something, Mei.

Say something so that you do not cry out.

‘Never,’ says Mei tightly. She would not have believed them even if she had. Around every corner of Hong Kong is 25someone peddling another spooky story, another popular myth; there is just as much gossip about the dead as there is about the living. Mei would explain all this, but something is shifting beneath her feet. This lady has obviously not wandered in here by accident. By accident is how Mei ended up in Kowloon, after taking train after train from Shanghai to Macau, after barely gaining a place on an illegal junk that foundered right off the coast, after finding herself pitched into the brackish water of the South China Sea, after swimming for hours, after washing up right onto a stowed-away beach with sand so white it scalded her eyes. She was all cut up on the oysters just off the reef and she left a bloody trail up the shore that the locals say is still there.

She stained everything on her way into this shop.

Mei doesn’t know what it is that suddenly gives it away: the naked gleam in the woman’s larger eye, with the other oddly empty. The way the woman is watching Mei; the way people once watched her.

This not-so-old woman is Holly Zhang herself.

The one-time glamour girl; the shining star of silent cinema. The symbol of a Shanghai that no longer exists. Instantly, without warning, Mei can feel the heat of languid, long-ago summer nights. She can smell a wonton seller’s shop, tucked into an alley like a card up a sleeve; she can hear the fickle scratch of a jazz record; she can see billboards on faraway buildings, brighter than the moon.

She can see blood on her hands, her clothes, in a puddle at her feet.

Mei might drop the banners again, but there is nothing left to slip through her fingers.

26George Maidenhair’s wife has entered Volkov’s Curio Shop. Has entered Mei’s existence. Has crossed her path. Everything until this moment was just a façade, a cover, just another sweeping-clean cloak, and now it is lifting. Mei has no idea how Holly has found her here, so deep in Kowloon it often feels like she is underground, but in a way it does not matter. The other woman must know that Mei has a history with George Maidenhair. Why else would Holly have come? Perhaps she discovered the custom-made paper shadow puppets that Mei once created for George. Perhaps she is driven by jealousy, by an erroneous assumption about the nature of Mei and George’s relationship – Mei is young and Chinese and pretty and poor, after all, and George is some three decades older, white and rich and powerful. Holly would not be the first to make that mistake.

Mei could easily just tell the truth. It is not like that, between me and your husband. It never was.

But by now there is so much bile in her throat, it pricks her eyes.

‘I want your help,’ says Holly.

Holly Zhang is a better actress than Mei ever knew.

What northerner can speak Cantonese like that, all nine tones, whetted like a knife?

‘I know who you really are, child. We’ve met before, you see,’ says Holly. ‘Years and years ago. Though you may not remember me, because you were the star then, and I was only one person in the crowd.’

3

Jiangsu Province, China, August 1937

Usually when my sisters and I hear the noise of the sweet-seller man outside, knocking his blocks of wood together as he passes through the village, we whine like pigs and Ba ignores us. Today I do not whine, and yet Ba buys me a handful of sugar melon sweets and gives me a tie-up bag to keep them in. He does not buy any for my sisters.

He does not explain why, so of course they only whine harder.

The last time Ba bought me a bag of sweets, it was right before the Dragon Boat Festival, at the start of summer. He did it to make me feel better, because my sisters had locked me up in the old ancestral hall of the sìhéyuàn compound down the road. They had been telling me stories about skeleton ghosts that haunt the hall, and they thought it would be funny.

Ma was the one who found me that day.

My sisters said they were sorry but they forgot about 28me. I still don’t know how long I was there; you can’t really tell day from night inside an ancestral hall.

I could not fall asleep that night.

Ma whispered to me, Whatever you saw in there, Third Daughter, you should not be afraid.

The real monsters live among us.

The real monsters look just like us.

But then Ma disappeared. Right after the festival.

I thought she might be locked in the ancestral hall too, but Big Sister says they checked there.

If bandits have kidnapped Ma, maybe I can buy her back with my sweets. I can trick the bandits into thinking they are worth good money – but then, in the stories that Ba tells us, bandits are always clever as monkeys; in fact sometimes they are monkeys.

Big Sister comes over to see what I am doing.

‘Do you want to play knucklebones with me?’ I ask hopefully.

‘No, because I’m not a baby,’ she says. ‘And I don’t want to touch your slobbery sweets.’

‘I haven’t put them in my mouth yet! Please play?’

Big Sister laughs, but without sounding happy. ‘You know what I think sometimes? I think Ma left because she couldn’t take how annoying you are. The sound of your voice, Third Sister, it drives people crazy. I bet that’s why she ran off!’

My hands close around my sweets.

‘If you shut up forever, maybe Ma’ll come back,’ says Big Sister, and she slouches away.

I feel very bad and shaky, like a beetle in a jar. 29

One day I must remember to ask the sweet-seller if I can borrow his blocks of wood to clap them over my sister’s mouth, or at least my own ears. Sniffling, I pile my sweets into a small shiny mountain and make it erupt, again and again, but in the end the only thing that erupts is my tears. Rickety old Nai Nai always tells me I should learn to eat my tears instead, like a good Chinese girl, and then I wouldn’t be so hungry all the time either. Sometimes I worry that’s what happened to Ma; that my tears washed her away.

At night, lying on the kàng beside a snoring Second Sister, I cannot sleep again. I cannot fall asleep well most nights. The darkness in our home is like the darkness in the ancestral hall, and I worry that it has swallowed me.

Let me out! Please, somebody! Let me out—

I jump off the kàng and I light a candle and everything returns to normal.

I know I must put the candle out before I get back into bed.

Hopefully, humans can live without sleep and we just don’t know it?

Carrying the candle I go over to the little side table where Ma makes her art. Or used to make her art. Ma is a paper artist: she can create anything so long as it is to do with paper, from simple sketches all the way to huge paintings and fancy shadow puppets. Now her pencils and paints and brushes are sitting here, waiting for her to come back, just like the rest of us.

Ma said she would teach me, one day.

Without thinking about it very much, I tiptoe over to where Ba sleeps, where he keeps a framed photograph of 30Ma by his head, and I pick up the frame carefully. In the photograph, Ma is bent over a little, looking away from the person taking her picture, and smiling. She is as beautiful as the moon goddess Chang’e. If you look right into the photograph, just the right way, you can hear her laughing. I call this picture-magic.

With the frame in my hot hands, I scramble back over to the art table and climb onto the stool. Then I grab one of her pencils and start to draw the image of her onto a piece of paper.

Sadly, it doesn’t look too much like the photo.

When I’m done, I make a tiny, sugar-melon-sweet promise to myself: I will not speak again until Ma comes back. Because for all I know, Big Sister is right, and Ma left because her ears hurt, because of me, because I am always talking. Or crying. Ma herself had such a nice voice, a voice like silk was trembling inside her mouth. I would never get tired of hearing her talk. Even better was when she sang.

Ba always says that she could have been a singer in a bright-light city theatre, in some other life, but this life was Ma’s fate.

I guess fate means that you have to sing in the darkness.

Today a man called Uncle and his wife have come to visit from Shanghai, the city on the sea.

Big Sister says they are visiting us for the first time ever because Uncle feels sorry about Ma being gone. I don’t see why he should feel sorry unless he took her. And I don’t blame him for not visiting before, either. Uncle is much 31too big for our home and has to duck his head so that he doesn’t hit the ceiling. He has short grey bean sprout hair and serious eyes and he is wearing a thick belted robe with long sloshing sleeves. His skin is like the morning sky, thin and bright.

Uncle doesn’t look a thing like Ma, even though Big Sister swears that he is Ma’s long-lost older brother. From her long-lost older family.

We don’t have enough chairs, so Uncle and his wife sit down on the kàng.

Uncle’s wife is called First Wife, even though he hasn’t brought any others. First Wife is frowny and plucked-looking. She has stiff wavy hair, like cloud-ear fungus cooking in a pot, and wears a qípáo with so many flowers sewn into it that I want to sneeze. She looks down at the kàng with her mouth crumpling up, as if she has never seen clay baked into bricks to make a bed. Then she gives me the exact same look.

Next to me, Big Sister mumbles that Uncle is fat with his family’s fortune and that our Ma grew up rich in Shanghai, but Ma ran away from home, and one day she happened to overhear Ba play the èrhú and then she just had to marry him, had to, even though he was poor as a raccoon dog, because she couldn’t get the sound of it out of her head.

But Big Sister is often fat with nonsense.

‘Do any of the children show talent for paper craft?’ Uncle asks Ba, who is standing by the stove, unmoving.

‘Third Sister makes wonderful cuttings,’ says Ba, which is a huge lie. Ma has never let me touch her cutting knives. Not even her sharpest pencils. 32

My face goes tickly because her pencils aren’t so sharp any more, now that I’ve been using them at night.

Uncle looks at me. ‘You’re how old, Third Sister?’

I clamp my lips together.

‘She has the manners of a donkey. Is she mute, or just rude?’ asks First Wife.

‘She’s six,’ says Ba, even though normally I am seven.

‘Come here,’ Uncle instructs me, and Second Sister shoves me forward. Uncle pulls from one of his scoop-sleeves a small white carved horse, opening his hand flat so I can see it better. His fingers are also white. Also look carved. ‘A gift for you,’ he says. ‘It’s hard-paste porcelain. True porcelain. Go on now, take it.’

I don’t want to touch his hand so I take the horse with two fingers.

I look over to Ba, who seems small and stooped.

‘Third Sister will not do,’ says Uncle. ‘You should be called Little Mei.’ He stands up and nearly knocks his spindly wife right off the kàng. ‘Well then. That is all for now. Perhaps you and I will see each other again, one day,’ he says to Ba. ‘If the Japanese army does not get in the way.’

My sisters look confused and maybe I do too, because in our village you only say the word Japanese in a weird baby-whisper voice.

I do not know very much about the Japanese except that sometimes we find guerrilla soldiers for the generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek lying dead in the ditches, and we don’t really know where they came from, and Nai Nai will say in that blaring baby-whisper, It was the Japanese, and then I imagine the Japanese like dragons, dropping people from the skies. 33

The list of things we cannot say aloud is getting longer: The Japanese. Ma.

Soon enough it won’t even matter that I’ve taken a vow not to speak; there will be so little anyone can say!

Uncle is leaving, sleeves splashing, robe lapping, First Wife following. I have seen pictures of people who wear robes like that, in Ba’s books. Old pictures. Old people. They have long braids like snakes down their backs. There is even a special name for these people, but I forget what it was.

Now I have a special name too.

‘You’re so lucky,’ says Second Sister, gawping at my new porcelain horse, but Big Sister only scoffs.

Before sleep-time, Ba takes out his two-stringed èrhú.

He hasn’t touched it since the day Ma left.

I feel like lightning bugs are lighting up my insides. Maybe he knows Ma is coming back? Could it be? Why else would he take it out suddenly?

We sit on the floor by his feet as he tunes the èrhú.

Everything is just as it was two months ago.

All that is missing in the world right now is Ma.

‘You want to try?’ Ba asks me, holding out the bow.

Ba was giving me lessons before Ma left. He wouldn’t offer like this unless she was coming back. She must be coming back. And when she does, I will be able to speak again. To sleep again. I nod eagerly and scramble up and take over Ba’s place and press my knees against the bulk of the instrument. I only know a few songs so far. Maybe that is why whenever Ba plays, the sound seems to last for hours, but whenever I draw the bow, it is over too soon.

4

Kowloon, Hong Kong, September 1953

Mei has spent all morning drawing a dragon, and it faces down.

Traditionally, a dragon that faces down cannot fly.

She could still cut it and try to sell it to tourists. The larger problem is that her hands have been working without her head. Maybe all artists know what this feels like; maybe anyone who creates anything knows it. Your hands take over, fervently sketching in the details of a dragon, adding sand dollar scales, tendrils curled into ringlets, toes like arrowheads, while your head is elsewhere. Your head is full of George Maidenhair.

‘Mei! Mei, are you up there? Mei!’

Mrs Volkova should really get a job at the docks. She could replace the foghorns.

Mei keeps working because Mrs Volkova probably just wants an antique chest moved out of the way, and tomorrow she’ll want it moved right back. Mrs Volkova 35likes to do things that make no difference; she is scared of making differences. Mei’s employer is an ancient and tetchy White Russian with a flimsy first name, Tatiana, and a tragic history involving a soldier husband who was shot on his knees for supporting the wrong side. But Mei never asks questions about Mrs Volkova’s revolution and Mrs Volkova never asks questions about hers. That is what their relationship depends on.

‘Mei! A letter’s come for you!’

Something shoots up Mei’s spine, down her arms, all the way to where she is holding the rabbit brush.

A letter?

It is possible that Mei has misunderstood. Mrs Volkova’s speech is more churned up than Mei’s paints, between Russian, some degree of Harbin dialect, and Cantonese without tones. But in any language, how can Mei receive a letter when she does not officially live here? When she does not even officially live? She has no legal status in this city. She is a refugee. She is somewhere between the place she comes from and the place she has arrived in, feeling wholly in neither, belonging nowhere. She is in the in-between place.

‘I know you’re up there!’ hollers Mrs Volkova.

Mei grips the brush until its shape burns her hand.

A large mapwing butterfly shudders close to the edge of her drawing-desk, perching on her dish of dye. Mrs Volkova likes to pin such butterflies to large wooden boards. Mounted behind glass, they glitter like the surface of the ocean, but Mei hates looking at them, hates how she can see the pin between her own eyes in the glass.

She has not moved from her chair. 36

The last person ever to send her a letter was George Maidenhair.

The mapwing takes off violently, in a flurry of flapping, knocking over the dish as it swoops away, drenching her desk blue. Paint drops off the edges, sloshes over the floor tiles. There are days when Mei might laugh at something like this; and then there are days when it feels like she is the one who is spilling out.

Mixing that dye, getting it just right, was two weeks’ worth of work.

Her life here in Hong Kong is five years’ worth of work.

Does she want to see that life tipped over too? Does she want to see it pool on the ground like rain?

Downstairs in the office, Mrs Volkova is sitting at her own desk, working on a Japanese netsuke, a miniature ivory sculpture. She likes to sand them down so small only she can tell what the netsuke was ever supposed to be. The walls are covered in Mei’s paper cuttings. Most strikingly the peony, over and over again, in different shapes and colours, though the holes pricked in the paper are always the same.

It is Mei’s best-selling work, but one could not say whether this is only because it is the one she makes most.

Mrs Volkova’s pet finch squawks a greeting at Mei from its bamboo cage, while electric fans, balanced on piles of newspaper, squawk harder. Mei has to wade her way in because the disarray in the room is considerable, piles upon piles of unidentifiable curios, anything that has ever happened to catch Mrs Volkova’s eye.

Mrs Volkova has a certain affinity for things that 37nobody else wants. Things that are beyond salvaging. That is how Mei ended up with her.

The finch blows out its throat like a toad. The Russian woman glances up at last, eyes narrowed, pointing with a magnifying glass towards the Yellow Mountain of correspondence at the foot of the desk. Mei does not know what it is about letters; why they always give off a whiff of being life-changing when they almost never are.

Tremulously, she picks up the envelope on top.

It carries a sickly perfumed scent, and at once she knows who has written to her.

But perhaps she already knew.

The envelope comes open easily, with one nail. The paper inside is light and flawless, and would be perfect for making paper-cut clouds. Sunny-day clouds. Not the fibrous dark masses Mei has caught glimpses of out the windows today. She inhales, prepares herself mentally. She must use her fingertip to help the strokes settle into their proper places, as she has an affliction known to her only as word-blindness.

It is not an accurate term, because Mei can in fact see words. If anything, she sees too many words.

‘Well, who’s written to you?’ says Mrs Volkova impatiently.

‘Holly Zhang.’ It is the sort of thing that sounds like a lie no matter how you say it. ‘She came into the shop a few days ago. She mentioned something about … but I did not think she would send a—’

‘You can’t mean the actress?’ Mrs Volkova is rising from her chair, which Mrs Volkova rarely does, evidently eager for Mei to read the letter out loud. The Russian 38woman might already be envisioning everything that lines the shelves of the curio shop lining Holly’s walls.

Holly Zhang does strike Mei as somebody who might buy dead butterfly boards.

Dear Miss Chen Mei,

I am pleased to invite you to join me at MAIDENHAIR HOUSE, 1 EMERY ROAD, VICTORIA PEAK, from FRIDAY 18th SEPTEMBER

For six nights

For six séances

In six different locations within Maidenhair or upon its grounds.

You are one of six spirit mediums whose presence I hope to secure for this occasion. One of you will be asked to leave Maidenhair after every séance, until there is only one remaining.

The final session will be an exorcism ….

If the exorcism is a success, the sole remaining spirit medium will receive a staggering monetary reward.

Feeling her mouth agape, Mei rereads and rereads the amount, in case it is her word-blindness acting against her.

Before she started working at the curio shop, Mei lived in the squatter’s villages out by Diamond Hill, chock-full of fellow refugees, all of them sharing their strips of sleeping mats, their lungs charring from paraffin smoke. Mei used to wake up at four every morning to toil in a plastic flower factory, working her fingers down to bone; eventually, she quit because she feared that a few more months of 39wrapping wire around fake flowers and her hands would get fixed that way, like a bear’s, and she’d never be able to cut paper properly again. Hoping to save her hands, she sacrificed her body: she became a white-flower girl in the red-light district of Mong Kok. There her hands did not fumble; they stayed clenched into fists until she lost all feeling in them.

Three years she spent flat on her back, living on next to nothing, until the day she happened upon the curio shop by chance.

Even now, she wakes up every morning and feels the tug of gravity, back towards that life.

Even now, she knows she could slip all the way down, effortlessly, the way those refugee shanty towns slide off the hillsides into the sea during the monsoons; like she was never here at all.

‘A competition?’ says Mrs Volkova. Mei’s employer is not easily taken by surprise. Mei imagines that comes with witnessing the people you love get shot on their knees; nothing will ever compare to the sound of those shots. ‘A competition to see spirits?’

Mei does not know Holly Zhang’s life story except in glints, but she knows that rich people love to believe in the supernatural. Maybe when you can have anything you want, you crave whatever feels impossible. Or maybe once you’ve achieved everything one ever could in this world, you become desperate to believe that there is some other world, somewhere out there, in which there is still more to achieve. In which you can start from nothing all over again. In which everything still lies ahead of you. 40

Likely, it is even worse for old rich people.

But that is not a problem that spirit mediums can solve, people feeling like ghosts in their own lives, of their former selves.

Mei cannot accept Holly’s offer. She should not accept. She should feed this letter to a fire. Not least of all because Mei would rather return to working for a mama-san in Mong Kok, servicing flat-eyed foreign businessmen, than conduct a séance. In some ways, it is about the same thing anyway, selling yourself for the entertainment and distraction of others, opening yourself up so that somebody else can forget their pain, just for a moment. Money never feels so grubby as when it’s placed into your hands while you have your eyes closed.

But the truth is that Mei is scared.

Six séances.

Six times she would risk becoming possessed. If she even made it that far.

‘I don’t understand,’ says Mrs Volkova. ‘Why is she asking you to participate in this?’

Mrs Volkova won’t believe Mei’s answer. Mrs Volkova believes in things that are tangible. She believes in netsukes. She will have crass follow-up questions, such as Could Mei do séances in the back room of this curio shop? Could Mrs Volkova offer special deals for the customers, half off a set of enamel water pipes and a reunion with your dead ancestors?

‘You look like you’re about to lose your breakfast,’ says Mrs Volkova bitingly, ‘so you may as well let this out too.’

‘I trained as a ghost-seer in Shanghai, Auntie,’ says 41Mei. The electric fans are still seething in her direction and her teeth have begun to chatter. ‘I was once the apprentice of a Great Master. We occasionally opened sessions to the public – Holly said she was present at one of these.’

Mei wouldn’t have noticed if so. There was only one person Mei ever saw, back then.

‘You’re telling me that you can commune with the dead?’

‘I don’t know. I have not used my Sight in years.’

‘All’s the better, I say,’ says Mrs Volkova, with a light scowl. ‘You will refuse her, of course. An aged has-been with too much money and nothing to do with it; I know the type! She wants a court jester, is all. Now then, the water is out again, so perhaps you could go on and take the tins down to the street pumps, unless you’re too good for it now, eh?’

It is not the reaction Mei expected. In fact, if Mei didn’t know better, she might think that Mrs Volkova cared about her and what she does, even though Mrs Volkova says that she will never waste her care on a human being ever again; on anything that cannot be repaired with tools like tweezers and fibre-tube torchlights. But more likely Mrs Volkova is already making ends meet well enough here in the earthy depths of Kowloon and doesn’t want anything to change. Change means gunshots one way or another, even if they’re not directly to the back of your head.

Upstairs in her bedroom her desk is dry again. Mei hauls out the Four Treasures of the Study: ink, inkstone, brush, and fine paper. She crafts her rejection with the utmost care. She is not as eloquent as Holly, she is not as educated, she is word-blind, but with good calligraphy, 42you can mask many things. A salted-plum salesman’s voice floats up from the street outside the window, advertising his wares; Mei’s mouth feels just like a salted plum. This is the reasonable choice, of course it is. To say no, to forget Holly’s face, to forget George’s name, to carry on in this cavern of a curio shop, mixing dyes, drawing dragons, dressing window displays, bracing for yet another barn-owl screech from Mrs Volkova. To go on living alongside her own ghosts.

But Mei’s hand has been working without her head again.

Dear Madame Zhang,

I am honoured to accept your invitation to

Revenge is the mapwing butterfly; if she grasps it too hard, she will kill it.

5

Jiangsu Province, China, August 1937

In the morning, my sisters and I visit Nai Nai at the sìhéyuàn. Nai Nai is grumpily sweeping outside the main entrance, and I am a little relieved. The ancestral hall is all the way across the central courtyard and Nai Nai is better than a tiger at keeping us out.

I show her my porcelain horse and she sneers.

‘Piece of garbage,’ she says. Nai Nai has a face like a hairy crab and no laugh at all. Not like Ma. ‘What will you do with something like that? Can you cook it? Eat it? Drink it? Wear it? Warm yourself with it? Give it to your father to sell.’

I shake my head stubbornly and slip the horse back into my pocket.

‘Uncle also gave her a new name,’ pipes up Second Sister.

‘A new name? I never heard of anything so pointless in all my life. What’s next? He brought new mud for us to step in?’

‘I want a new name too,’ protests Second Sister. 44

‘Shoo, you naughty girls, Nai Nai is busy!’ she barks, waving her broom like she’ll beat our backsides with it, though she never has, so we’re not scared. She returns to her work, bundling the dust by her sandals. She has tiny feet, like a sandpiper. A fortune-teller once told Nai Nai’s parents that if they broke her foot bones, Nai Nai would marry a rich man, so they did this, but the fortune-teller was wrong. Nai Nai married a poor man.

And now she has to do the sweeping on a rich woman’s feet.

I turn around when we reach the gates, to wave goodbye, but Nai Nai is not even looking at me. Her face is gleamy red, like a New Year’s envelope, and her eyes are wet. She rubs them with her sleeve, but it doesn’t help. I want to tell her that soon everything will be alright. I want to tell her that once Ma is home again, Ma can make new lotus shoes for her, the ones that make stubby feet look very fancy, instead of the ugly clogs that Nai Nai is wearing now. Ma can also help with the sweeping, because Ma’s feet are perfect and unbound, though they have a tiny bit of webbing between the second and third toes, just like mine.

I open my mouth again, just for a second—

But then, oh! A frog jumps out in front of me.

A few weeks ago we had the great idea to trap golden frogs from the pond and then release them in the courtyard, to annoy Nai Nai. But she caught most of them quickly, because she’s faster on half-feet than most people are on full-feet, and worst of all, she ended up boiling them and eating them.

There are people in the world that it’s just not funny to play tricks on, and Nai Nai is one of them. 45

I wish I were one of them. Then my sisters never would have locked me in an ancestral hall to begin with. Then Ma might not have left in the first place.

Much later, on the kàng, my eyes are heavy and I think that maybe, just maybe, I will fall asleep fast tonight, but before I can, Big Sister rolls Second Sister out of the way and lies down next to me, which she almost never does because she thinks I stink like a yellow ox.

‘Ba’s going to take you on a trip tomorrow,’ she says, very quiet. ‘Just you and him.’

I don’t say anything because even though Big Sister is older and smarter than me, she does like to tell lies. I knowI don’t smell like a yellow ox. Oxen are very, very smelly. And Ba has never taken any of us on trips before. Where is there to go? China is mostly fields and fields and fields until you fall off into the sea. That’s why they build cities on the coast, I think; to stop people walking right in.

‘For goodness’ sake, Third Sister, you should just talk again,’ says Big Sister. I can tell she is rolling her eyeballs all the way up and down, the way she often does. Ma used to say her eyes would get stuck like that, like a flatfish’s. ‘This is ridiculous. Ma is dead. Okay? She’s dead.’

When I don’t answer, Big Sister turns onto her side so we are looking right at each other.

‘You don’t believe me, huh?’ she says. ‘Ma is dead. Everyone knows it. They just don’t want to tell us the truth.’

For the first time, I realise that Big Sister looks the most of the three of us like Ma. In the face, at least. She doesn’t have the webbed feet. Big Sister is also the smartest of the three of us. She taught herself to read using Ba’s collection 46of books, and she even taught Second Sister. She tried to teach me too, but even if I’m not as stinky as an ox, I am as bad as one with learning characters.

Ma is not very good either. That’s why she scribbles a dainty little peony flower onto all of her artwork, to mark it as hers, instead of her name.