Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

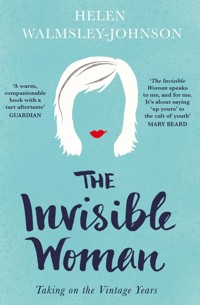

'Stylish and wittily written … a brilliant read that should encourage us all to challenge the cult of youth, and learn to love ourselves a little more along the way.' My Weekly There's nothing middle-of-the-road about middle age. From coping with bodies that are 'heading south' to rampant ageism in the workplace, this time in our lives, in the words of Bette Davis, 'is no place for sissies'. From family, finances and work to cosmetics, fashion and sex, 60-year-old Helen Walmsley-Johnson – the irrepressible voice behind the much-loved Guardian column 'The Vintage Years' – shows, with warmth and a wicked sense of humour, how we can reinvent middle age for the next generation of women.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The

Invisible Women

The

Invisible Women

HELEN WALMSLEY-JOHNSON

Published in the UK in 2015 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

ISBN: 978-184831-844-1

Text copyright © 2015 Helen Walmsley-Johnson

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any

means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Janson Text by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK

by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

Introduction

1. Little griefs

2. Reasoning backwards

3. WTF

4. Pick a crisis

5. Trivial pursuits?

6. A hundred billion neurons

7. Skin

8. The end of the beginning

Further reading

Acknowledgements

Introduction

‘Old age is no place for sissies’

—BETTE DAVIS

This is a book about ageing. Specifically it is a book about women and late middle age. I am middle-aged (there, I said it) and since you’re reading this, I suspect you might be too. If I’m truthful, I was mostly through my middle age and out the other side before I even accepted that I was middle-aged. In this you and I may find we have a certain amount in common. You perhaps also share my frustration at the general lack of information, the attitudes of the media (mainly) and others (generally), and at the way we are portrayed – all of which add to a slight feeling of unease, which begins to make itself part of everyday life. A faint sense of dread at the onset of middle age is entirely understandable, although we’d probably be better to call it what it is – fear. Fear that ‘life’ as we know it is over, fear for the future and fear of the unknown. Middle age has become the uncharted grey bit on life’s map, the terra incognita wasteland we must navigate before we can get on with being properly old. When we’re old we hope we’ll know who and what we are; the bit that gets us there is much harder to determine.

Let me start with a question or two. Would you place yourself with the ‘drag me kicking and screaming into retirement’ middle agers, or are you one of the ‘thank God that’s all over and I can put my feet up for a bit’ group? Or perhaps you’re one of the women who at some point in the last decade wandered unintentionally up an economic cul-de-sac and spend days and nights wringing their hands and worrying about how they’re going to struggle through to the relative security of a state pension.

There’s a lot of noise made by the Middle Age Resistance. They’re the ones tearing about with their sports cars and motorbikes, the ones flouting every age-conscious style rule in the book; they’re the ones who backpack around the world on their children’s inheritance and pop up on your telly and in your newspapers pulling, God help us, ‘wacky’ stunts; they’re the rowdy groovers at Glastonbury having loud thrice-nightly sex under canvas; they’re the ones who resist, resist, resist and vow to go down in a blaze of glory shouting, ‘Look at me – nothing middle-aged here!’ Meanwhile the accepters are quietly, and perhaps a tad smugly, getting on with kicking back, shooting the breeze and being, well, middle-aged but in the more conventional sense as we are given to understand it, comfortably cocooned in their mortgage-free, pension-savvy world with the drawbridge firmly up (‘Crisis? What crisis?’) and accepting this latest life stage with equanimity and quiet resignation. Apparently.

Why is this age group presented as polar opposites, aggressively divided on the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ ways to grow older? What of the ones who have no option but to grit their teeth and get on with life as they always have but find the age cards stacked against them? Why does the media always depict the middle-aged gilded with comfortable privilege? Isn’t there a case for a fresh look at middle age? There is growing interest in this further transitional phase of life and it provides us with an opportunity to position it as something more interesting, less frightening and as something concerned not with loss but with gain; a chance to redraw outdated concepts of beauty; to appreciate wisdom and experience; as a more comfortable mix of resisting the depredations of an ageing mind and body while also gracefully accepting and embracing the inevitability of it? There is a case to be made for preparing for middle age – physically, mentally and financially – and, during middle age, preparing for the old age that will follow … if we’re lucky.

Even the Oxford English Dictionary herds middle agers together with a definition of ‘the period of life between young adulthood and old age, now usually regarded as between 45 and 60’ – a stark definition of fifteen years that feels like quite a stretch; there’s a huge physical and psychological difference between a 45-year-old and a 60-year-old; just as there is between a 20-year-old and a 35-year-old at the other end of the age spectrum. It’s simply not helpful to lump the whole group together.

In any case, I doubt many 45-year-olds think of themselves as middle-aged, I know I didn’t. Nor did I wake up one morning and think ‘here it is’. Middle age arrived in me – roughly five years later than the OED definition – like puberty, with spurts, longueurs and occasional tears. At times I would be completely, stormily, at sea while at others I felt in an odd state of languid, drifting suspension. I would describe where I am now as battle-weary contentment. ‘Contentment’ is a word not much heard in relation to middle age and I’ve had to find my way through a fair few dense thickets of self-doubt, melting confidence and spitting rage at a world that won’t fight with me to achieve it.

I wonder if any other age group is subjected to quite so much ill-defined and random generalisation. Take the popular misconception that, say by 50, you will have achieved what you’re going to achieve – you will have had your shot at life, your best is behind you and now it’s time to accept that you should drift quietly and without fuss or protest towards retirement. That is what we’re told and, whatever we ourselves believe, there’s a large chunk of society who do indeed think that by the time we’re 50 we middle agers have zipped up the well-lit motorway of earlier life, bounced over the junction at the top and are now at least halfway down the B-road on the other side with no brakes, no lights, bad eyesight and a shaky grip on the steering wheel. Do I accept that? No, absolutely not. To continue the metaphor, I’m doing my damnedest to stay right there on the road, but I’m also adjusting my speed to take into account the age of my engine and bodywork.

The ‘young-ist’ culture of television, radio and the rest of the media has, for the most part, already consigned middle agers to a life less interesting and a road less travelled. What arrogance to prematurely chivvy us off into a routine of afternoon naps and daytime television! Speaking for myself – and while admitting to a slight fondness for a post-prandial snooze – I’m still working my socks off. We, the middle-aged, have so much to offer. We must assert our right to make plans, be heard, have interesting, useful lives. Historically middle and old age is when one generation passes its wisdom on to the next – a useful and admirable tradition worth perpetuating if only we could regain our lost voice. We should not allow our opinions and experience to be dismissed, however benignly, and we should not allow ourselves to be ignored. We should decide for ourselves what we want to do and when we want to do it, and we should fight to restore dignity and usefulness to this forgotten age. Isn’t that just as important as the right to have pink hair, wear Doc Martens or ride a Harley Davidson? I do not accept this ‘writing off’. I do not accept invisibility.

For me personally, the past few years have been a period of discovery – the discovery that contrary to received media wisdom I am still in possession of a fully functioning brain and still have the intelligence to put up a convincing argument; that while I can still be perved at from a passing car I can also suffer ageist abuse in a busy London street in broad daylight; and that I am perfectly capable of navigating my own solitary way from London to the South of France by train without being mugged or getting lost. Nonetheless, the day came when I ticked the ‘age 55 to 64’ box on a survey form and it struck me quite forcefully that I had at last become a proper grown-up and was officially middle-aged. Not a welcome moment if I’m honest – does anyone truly look forward to getting old? But the moment also came with a certain sense of … achievement. Against all the odds I have survived this far. As moments go, it was pretty profound; it was one of those moments that make you stop and think for a bit about life. I’m one of the fortunate ones: I feel strong and healthy, I feel reasonably hopeful and, dare I say it, I feel an exciting little thrill of possibility, an opening up of new horizons. Despite my recent battering in one of life’s storms, I feel cautiously optimistic.

On the other hand (for such is the seesawing of emotion that accompanies this time of life) I also feel a tad miserable, a touch apprehensive and quite a lot fed up, largely because the ‘age 55 to 64’ box is also the last-butone box; it is the God’s waiting room of my form-filling life. My limited ration of optimism is nibbled down further when most of what I read, watch or listen to about middle age is either patronising, reinforces the popular misconception of a slow decline, or is a broad comedy generalisation; in addition, over the last couple of years I’ve seen a new kid on the block of ageist debate – the ‘them’ versus ‘us’ argument. This is the one that says the older generation is robbing the younger one of its future; that we selfishly live in overly large houses, hog jobs and are unfairly protected against times of economic hardship. There’s barely a week that goes by without me going nuclear about something or other to do with middle age as portrayed in the media. It seems that for the over-50s each day brings the invention of some fresh new paranoia, either ours or someone else’s. Ageing I can accept as inevitable, but the way it is demonised, demeaned and ridiculed by the media is another matter. This helps no one. This I will fight … this I will resist.

By now my personal list of annoyances would probably extend to several editions but, in its abridged form, it’s this:

Uncooperative and badly made clothing, such as tights, socks and t-shirts that twist when you put them on, shirt buttons that fall off and hems that drop on their first outing, anything that requires breathing in to do it up, etc., etc. I am no longer designed to wrestle with it, and I don’t have the patience.The term ‘age appropriate’. What is that?People who call me ‘dear’ or ‘love’ in any sense but the ironic.Telephones with large buttons of the type advertised in the back of certain magazines – see also walk-in baths, floral loose covers for my sofa, thermal knickers. Over my dead body.Callers to You and Yours and Any Answers on Radio 4 – occasionally I emerge from the fog of a radio-based rant with my hand reaching for the phone and I’m terrified that one day, possibly quite soon, I will turn into someone who telephones Radio 4.Packaging – if tubs of soup were the only things standing between me and starvation I would die because I can never get the damn things open – see also tubs of vitamins, cocoa and toothbrushes.Cheerful coffee shop staff – it’s undignified. You do not know me and I do not know you. Let’s keep it that way.Mirrors all over the place in shops and department stores – my eyesight is not what it was and I’m apt to walk into things. I don’t like what they show me either (a middle-aged woman with hair like a dormouse nest who may or may not be me. I don’t know).Fitting rooms in department stores – mainly for reasons of the cruel and merciless lighting but also because some bright young thing always whips the curtains open when I’m trying to pull up a pair of size 12 trousers over my size 14 backside. (A younger me would never have worried about this – she was a permanent size 8, goddammit.)Hair flicking on public transport – hygiene and envy, pure and simple.Young people in groups – because I now find them vaguely threatening and know that while I am still able to run I will not be able to run fast enough. Groups of young people must be passed silently, avoiding all eye contact.Shop assistants or anyone else who makes assumptions without enquiry – just because my face says I’m middle-aged does not mean I want you to pigeonhole my wardrobe/menu choices/shoe requirements/understanding of modern technology, etc., etc. ad nauseam.Given my sporadic rants and the way I feel about raising the profile of the middle-aged, I had no qualms at all about accepting an invitation to write a weekly column – ‘The Vintage Years’ – for the Guardian website. It began as a fairly straightforward idea – writing about style for older women – and has slowly become something more. At first, women were the ones reading and responding, but then a trickle of regular male readers began to add their two penn’orth to the discussion, which raised a set of other connected issues. When younger people chipped in with their own worries and anxieties about ageing, I began to realise that this ‘problem’ (if we choose to see it as such) of how we approach middle and old age is not restricted to those closest to it at all. If a young woman of 24 is already afraid about what will happen to her life and relationships as she begins to show signs of age, I think we have to acknowledge that there really is something wrong with the way we see the process of ageing and older people. It is, after all, an entirely natural process. Ageing is a physical process that needs to be accepted with serenity; we must learn to manage our expectations sensibly and not live in denial, or fight back with cosmetic surgery and treatments we can’t afford, most of which just make us look weird. That we will all age is inevitable and inescapable but it doesn’t alter the person we are inside; our character, memories, strength, personality and intelligence are what make us us. We are defined by our family and friends and those who care about us. How have we overlooked this and allowed a youth-obsessed media to cast the runes on our behalf? Without our steadying voices they have conjured a roiling, festering manifestation of age-related neuroses. Well done us.

With that in mind, it’s perhaps not surprising that the pieces I write for the Guardian and others about what I, as a middle-aged woman, think and feel about getting older, and what it does to my sense of style and self, trigger far more debate than when I write a standard reporting piece from, say, London Fashion Week. I allow myself a degree of optimism at the reassuringly large appetite for discussion about ageing and how it affects us, both physically and psychologically. When the ‘Vintage Years’ column began, comments were, for the most part, from readers in the UK, but after a few weeks readers from around the world began to join in, voicing much the same anxieties whether they were in Sydney, Singapore, New York or Huddersfield. That in turn inspired me to start a Twitter account – @TheVintageYear – where I encouraged people to bat around thoughts and opinions in 140 characters (or fewer).

Eventually I tweeted this question to my followers: What are the three things that worry you most about getting older? I can tell you that it’s comforting to discover that the same things are keeping all of us awake at night, irrespective of age, gender, nationality or income bracket. According to my poll the top three are:

Loss of health/memory/marblesLoss of independence (via health or finances)Loss of loved onesYes, it’s all about loss.

Loss in today’s acquisitive, goal-driven society can feel like defeat. This is true even of small, inevitable losses such as the loss of our youthful appearance. To accept our encroaching lines, wrinkles and grey hair has come to be regarded as some kind of personal failure – we are the losers, the defeated. But we’d be better off accepting this more superficial kind of loss. Time will inevitably steal from us anyway, but time also allows the blow to fall slowly, incrementally, and replaces what’s gone with something else, if we have the courage to allow it. There are, after all, much worse things we may have to face – as recognised by my Twitter respondents.

Losing the people we love, for example, is a far heavier blow, probably the heaviest of all, but it is also the nature of love and life. To risk knowing love means we will know the grief of loss too and this is something that must also be accepted, although it is easier said than done and takes a great deal of time and effort. Fighting a few age spots (or are they freckles?) and laughter lines (or are they crow’s feet?) pales into insignificance against the strength and courage required to endure close personal bereavement.

And then there are the other, more gentle losses, like the sweetly painful joy of seeing one’s children grow into adults and leave the family home to build their own lives. This loss we must also accept but it is a loss tempered with pride, hopefully, at a job well done (and maybe just a little regret for the things we didn’t do quite so well).

Conspicuously absent from that top three worries list, except inasmuch as it comes under ‘loss of health’, is the possibility of terminal illness. We don’t discuss it, do we – in the same way we don’t talk about death itself, or the unopened letter from HMRC on the sideboard. It’s the elephant in the room; the haunting fear we dare not mention – as though to do so is to hand over a personal invitation for the Grim Reaper to join us for tea and biscuits on Wednesday week. And it doesn’t help to think of life itself as terminal, which it is, or that the C-word (cancer) is quite commonly a disease of age. (In his book The Emperor of All Maladies, Siddhartha Mukherjee explains that ‘cancer is built into our genomes’ and that ‘as we extend our life as a species, we inevitably unleash malignant growth’ – further adding that ‘mutations in cancer genes accumulate with aging; cancer is thus intrinsically related to age’.)

It’s very strange that we avoid searching for facts when what scares us most of all is the unknown: the not-spoken-about hidden things. That’s what makes us shout Switch the bloody light on! when someone in a film creeps down the dark, dark stairs to the dark, dark cellar with only a torch, a safety pin and a bar of soap. If we know, if we can see and understand what we’re dealing with, wouldn’t it go a long way to removing much of the fear? We really must be brave and stop being quite so squeamish about the things we’d rather not know because we’re afraid of them. It’s an entirely understandable and very common fear of something that is, after all, an undeniable fact of life (and, in the case of death itself, inevitable) so why do we do so little to address it? Is it that we can’t find the information in accessible form, written in calm, straightforward language? And, by the way, you will eventually open that letter from HMRC and find it’s nothing more threatening than your new tax code.

That brings us to that other worry – money, and the possibility of not having enough of it. In the spirit of honesty I must tell you that this is more likely than you might have supposed – the fabled ‘grey pound’ may not be quite as plentiful as we have been led to believe. According to research undertaken by Prudential, one in five retirees will retire into debt with an average monthly debt payment of £215. The trend is upwards, but as ever with our generation, there is a notable lack of useful data. Fortunately, our finances are one other thing we can work on to improve now, if we think and plan, take our heads out of the sand and refuse to accept what we’re being palmed off with. It makes me very cross indeed that once you’re past 50, and regardless of what’s written into employment legislation, if you’re looking for a change of career or just looking for a job, any job, the general perception is that as a middle-aged person you’re past it; and that assumption will be made before anyone has even clapped eyes on you. How dare they?

From my own experience this prejudice is now countrywide and ubiquitous, although it used to be not so much of a problem inside London as outside it – and I base this observation on my relocation to London when I was 45 (officially middle-aged according to the outdated OED). In Leicestershire, where I’d lived much of my life, I was ambitious but unable to get so much as a sniff of any job commensurate with my experience and qualifications; London proved a much happier hunting ground … then. However, a more recent job search proved frustrating (just shy of 500 applications resulting in only three interviews) and this, I discover, is a far from isolated experience for a fifty-something woman. In the capital what seems to be emerging is a narrowing of the white-collar recruitment pool at both ends of the age spectrum, with the youngest, least experienced applicants losing out at one extreme and the middle-aged candidates at the other. It’s worth noting that between the first quarter of 2010 and the last quarter of 2013, unemployment among women aged 50–64 increased by 41 per cent from 108,000 to 152,000 nationwide. In comparison, unemployment in the same period among all people aged sixteen and over increased by just 1 per cent.* That current government statistics indicate otherwise would be, I suggest, more to do with the widespread use of controversial ‘zero hours’ contracts than anything else.

A date of birth may no longer go on to a CV but anyone with half a brain can work out a candidate’s age from the other information it contains. It’s hard to see this as anything other than age discrimination. You could make an argument that older people will expect salaries commensurate with their experience, and this is what employers are wary of – but where does that leave the research cited in at least half-a-dozen of the reports currently in circulation that what older women need more than anything is flexibility? That, in other words, the salary is less important than having a choice about how you earn it? Reasonable hours of decently paid part-time work are the Holy Grail.

It seems the situation for the older jobseeker is just as desperate as it was when time was called on ageism by the Age Discrimination Act of 2006. If anything it’s worse because the prejudice against and the unwillingness to employ an older worker is less in your face and more nuanced. The ‘sits vac’ is full of ads employing a variety of ambiguous words and phrases that provide an excellent smokescreen against prosecution, although it’s quite clear what they’re driving at. There is the phrase ‘recent graduate’, which is unlikely to be someone of 40-plus, much less someone in their 50s, or experience ‘gained in a recent gap year’ is mentioned. There are constant references to ‘energetic’, ‘lively’, ‘demanding’ and ‘to fit in with a young team’ – hinting at youthful enthusiasm and stamina rather than middle-aged stability and experience.

A lot is being made of older people becoming freelance or self-employed – the so-called ‘olderpreneur’. Indeed, we are encouraged to choose that way but although we’re very good at self-starting, it’s a plan that does rather rely on having some start-up capital in the first place and it doesn’t remove the problem of the persistent ageist attitude to older workers, which lies at the heart of so much of this issue. To say, as many reports do, that we are choosing to become self-employed is quite simply wrong. It is not a choice when it is our only option.

By 2020 over a third of the working population – and half the overall population – will be aged over 50. The retirement goalposts keep moving and as they inch ever nearer to 70 we’re finding that all of us will have to work longer, which would be fine and dandy if there wasn’t such ingrained prejudice towards us. We need to rethink the way our work in middle age prepares us for old age. My own observations seem to suggest that a great many of those earning the ‘grey pound’ will finish up minding a supermarket checkout.

And that’s another problem right there – that at some point, and especially in tough economic times, we the middle-aged are expected to step aside and leave the field clear for the young – to which I would respond with two fingers held firmly and proudly aloft, reinforced with a concise verbal instruction in Anglo-Saxon. We, I, have a perfect right to employment but if we’re to get it we have to conquer our aversion to showing off what we can do and blow our own trumpets quite a bit more than we do currently. After all, if we continue to work and earn then surely we’re not the burden on society that pernicious propaganda suggests we are.

It’s inspiring to see people doing brilliant, unpredictable things and especially when it’s us, the middle-aged. Where are the stories of those of us who have chosen to go off and do a PhD in Advanced Nuclear Physics after spending the last 20 years working as a librarian, a train driver, a traffic warden, a doctor or an actor? Or perhaps a soldier who became a shepherd? Or a hairdresser who started up a cheese-making business? Perhaps we’ve had enough of working in an office and decide to open a restaurant. Or write a book. Why can’t we hear and see middle-aged women who’ve done these things, women who would inspire us? We need role models but where are they? Whatever we decide to do and whenever or wherever we decide to do it, it should be our decision to make, but wouldn’t it be bloody marvellous to know how someone did what they did and what they were thinking when that life-changing opportunity presented itself?

I want my life beyond 50 to be an enthusiastic life crammed with ambition, hopes and aspirations. I want Life (with a capital ‘L’) but it won’t come to me – I have to go out and hunt it down. I’ve got to grab it by the throat, beat it into submission and make it into something that fits me. I’ve already decided what I will put up with and what I won’t. And that brings me to why I wrote this book.

Last year, I decided I was going to write something useful about middle age – to take a look at what happens to us, why it happens and what, if anything, we can do about it, which bits we accept and which bits we make a bit of bother about. From midlife crises and whether they exist to brain fade and invisibility; from enduring the ‘little griefs’ when everything starts to head south to how attitudes in the media and marketing affect perceptions of age; and to look at the things we’re afraid of. I want to prod my inspiring and gutsy, funny and opinionated, waspish and resilient generation into making a noise, into demanding the respect, dignity and rights that we’ve earned and deserve. I want to make those grey bits of the ‘life map’ our bits, and as interesting to drive as B-roads often are with all their ups and downs and twisty corners. I want us to know how to look after our own bodywork and how to tune our own engines to sing like an Austin Healey 3000 at full throttle. I want us to make the most almighty fuss and reinvent middle age for the next generation.

That my own life should take an unexpected detour along a cliff edge while I was working on this book made the act of writing it extremely difficult but I don’t think I would have understood anything nearly so well as I do now if I hadn’t been peering over the precipice.

Footnote

* The Commission on Older Women, Interim Report, September 2013

1

Little griefs

‘Maybe it’s true that life begins at fifty. But everything else starts to wear out, fall out, or spread out.’

—PHYLLIS DILLER

Age, the traitor, crept up on me. For a very long time it seemed as though nothing changed and I might remain in my heyday forever after all, but then, quite suddenly, things began to creak and fall apart, like kitchen appliances before Christmas. Which bits of me had been physically where became more of an abstract memory; as did their size, shape and the existence of clothes that fitted properly. In some ways it was easier for me, as a woman, to acknowledge the onset of natural decay and disintegration because biology conveniently provided a few helpful markers, largely arranged around the business of procreation and therefore largely to do with hormones. Men – and I think most women think this – seem to get off quite lightly with a smattering of relatively minor stuff. Hormones play their part here too, but the general perception remains that men improve with age while women start to crumple up like Dracula on a sunny spring day. For the most part men seem to weather the years in a pleasantly worn and crinkly way, like a comfortable old sweater, but whatever happens to the exterior there is still the younger man, just there, twinkling away behind the eyes.

Traces of a younger self still reside in every middle-aged person, of course. I remember how my nan used to tap her forehead and say ‘I’m still eighteen in here’. I have a theory that most of us, men and women, arrest our emotional development, not at eighteen, but somewhere in our 30s. As Rolling Stone Keith Richards (69 and looking 89, God love him) said, ‘How could it be our 50th anniversary? I’m only 38.’ Personally, I thought I was 31 until I was about 46. When I was 31 I was a tiny elfin blonde in a pink lamé dress. It is an image preserved in a photograph and it was the time when I perhaps liked myself best, physically. In all other respects I was an idiot.

It just never occurred to the Younger Me that one day she’d be 59 but there it is, in black and white, on her – on my – birth certificate. Undeniably there is more of my life behind than before me. There are the little ageist prompts my body delivers daily with a soft brush of sadness, an irritating reminder that once upon a time I got out of bed in the morning without producing a concerto of squeaks, creaks and groans. I remember being able to sit up in bed (without using my elbows), stretch (without locking my back) and face the world with a dazzling smile. Happily the smile is still there – when I do eventually smile (though I am not, and never have been, what you might call ‘a morning person’) – that much hasn’t changed. To be honest, I took all that rude good health for granted. I recall an effervescent feeling of energy and enthusiasm in the same way I remember snowy winters and endless perfect summers.

There are not many days that pass without a few tangible reminders that tempus is fugiting, and much faster than I would like. These reminders add up to little chapters of mild distress that I am ageing and the fact that I really am 59 has become impossible to ignore, although it seems equally impossible to accept. The Younger Me in my head and in old photographs starts to show signs of separation anxiety even before we – I – have got out of bed in the morning; but then that Younger Me usually got a better night’s sleep than the older me does. It’s not a great way to start the day and it’s only one of a growing catalogue of small sorrows and minor niggles that plague me on a regular basis and at different hours of the day and night. For a start, I’m not always entirely sure when my day begins any more but perhaps you’ll understand what I mean if we take a gentle canter through what might be a typical day; we’ll begin, as I often do, in the middle of the night.

SLEEP

The Younger Me used to go out like a light as soon as her head hit the pillow and stay like that for a good seven or eight hours. Sadly, this is no longer true. I wouldn’t stake a fiver on a whole undisturbed night’s sleep these days. A bit like playing roulette, there is no logic to a win. So I go to bed simply because I love my bedroom, my bed and a good book. (A psychiatrist would probably tell me I have a womb fixation.) I’ll bust a gut to get on a late train home from the other end of the country just to sleep in my own beloved bed, but my bed isn’t always my friend. I bought a feather topper because an over-firm mattress and imminent rain sets off a ripple of sciatica. I invested in an expensive, warm-in-winter-cool-in-summer duvet. My sheets are nubbly, soft French linen. I’ve taken a lot of time and trouble over creating a cosy cocoon in which sleep will happen. And it does, for the first three or four hours, but then I’ll be screwing my eyes shut against the three o’clock wee.

The three o’clock wee isn’t always driven by a genuine need to wee but by the time I’ve convinced myself that I don’t need to wee I’m awake and worrying that I need a pre-emptive wee anyway. Also known as the ‘investment wee’, this is the wee you have even though you may not necessarily want to because it saves you having to wee later, at a less opportune moment. So (eyes opened as little as possible) I fumble my way to the bathroom before returning to bed, where, with an infuriating sense of entitlement, the cat’s now occupying the lovely warm hollow I left two minutes earlier. I am, of course, thoroughly awake. So I eject the cat and read until I nod off and my book smacks me in the face, waking me up to begin the whole wretched business all over again.

I know this three o’clock waking has somehow become a habit but it’s one I don’t seem able to break and lately I find it coincides with the kind of drenching sweat you should only see on a Grand National winner. Nobody warned me about this. I naively thought a hysterectomy and HRT would spare me much of the horror of the menopause (at least that’s what my consultant told me) but oh no. Now I find it’s caught up with me just the same. There is nothing to be done when you wake up in a bed mysteriously transformed into a Turkish bath – or rather, there is: you have to get up and change the sheets, pyjamas, everything, otherwise your bedroom takes on that peculiar musty scent indicative of a resident adolescent. The worst thing is the anticipation. The anticipation of it sometimes wakes me up and I feel it starting. It’s not dissimilar to an efficient central heating boiler – it fires up silently somewhere around my middle and in a matter of seconds everything is aglow but at least that has the advantage of allowing some precautionary shedding of bedclothes, so not all night time waking is bad.

But then there are the Technicolour nightmares, which are bad and arrive in a chicken-and-egg partnership with the sweats. And there’s having one ear cocked for someone trying to nick the car. There’s being asleep yet not asleep, while a parade of passing night-distorted worries nip and pinch so that every time I feel myself slipping drowsily into the arms of Morpheus I jerk back up again in alarm. There’s the recurring ‘zombie dream’: will the bolt on the front door hold, is the cat safe, do I have enough food in …? None of this nonsense ever kept Younger Me awake.

I had hoped that having arrived at a time of relative peace in my life and not, for example, having one eye on the clock waiting for teenagers to arrive home ‘quietly’ at 2.00am would mean I’d sleep the deep and satisfying sleep of the untroubled. Not so. In the absence of more mundane things to worry about my brain is in overdrive, busily inventing ever more fantastical reasons to be awake – the other night I dreamt I was making Brian May and a badger a mug of Bovril. I ask you, what hope is there?