Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

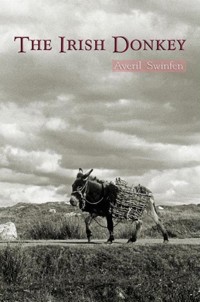

The donkey is an integral part of the Irish landscape and tradition. This new, enlarged edition of a book originally published in 1969 traces the evolution of the species from its origins in Africa and central Asia to its arrival in Ireland in the early mediaeval period, and the multiple uses to which it was put in transport and agriculture. The life of the donkey is described with tender insight drawn from the author's own experiences, from breeding to welfare, whether as pets or beasts of burden. Its afterlife in literature, folklore and mythology is evoked by James Stephens, Rev. J.P. Mahaffy, R.L. Stevenson, G.K. Chesterton, Patricia Lynch, Patrick Kavanagh and others. The ass in the Bible, its cousin the mule and its relatives abroad also find a place, ranging from Somalia, Kenya, Iran and Andalusia to Kentucky and New Orleans, concluding with the legendary donkey of the 1915-16 Gallipoli Campaign. Photographs by the author and by Bill Doyle, with a select bibliography, make up this popular history of one of Ireland's most beloved animals.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 213

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2004

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE IRISH DONKEY

Averil Swinfen

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

Contents

Title Page

Foreword by Vincent O’Brien

Preface & Acknowledgments to the Lilliput Edition

Preface & Acknowledgments to the 1969 Edition

Introduction

I. THE DONKEY IN IRELAND

1. Origins

2. The Batty Ass

3. Introduction to Ireland

4.UsesinIreland

5.BirthofaStudFarm

6.AStudYear

7. As a Pet

8.DonkeyLife

9.Care

10.AndMoreCare

11. Decisions

12. The Truth and Nothing but …

II. THE DONKEY IN THE WORLD

13.Derision

14.SomeScatteredRelations

15.AmongstOurWriters

16.InVerse

17.DonkeysandtheirOwners

18. Folklore, Mythology and Tradition

19. The Ass in the Bible

20. An Honorary Member

Select Bibliography

Index

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

IAM HONOURED to be the first person allowed to read the manuscript of this book, TheIrishDonkey, by Averil Swinfen whom I have known for many years. A lover of animals, she has been keenly interested in them all her life. In the past, when neighbours in County Cork, we shared a mutual love of, and interest in, horses. Indeed when I decided to set up as a trainer she was, though not one of the luckiest, one of the first owners to send me a horse, and she was an enthusiastic supporter in those early days. Though the course of her life led to England for some years, it was inevitable that on her return home to Ireland, her children by then grown up, she would once again interest herself in animals. This time the animal to which she chose to devote her experience and talent was the donkey.

Donkeys are so much part of the Irish landscape and tradition that they have been too much taken for granted. With the development of better means of transport, and consequent decline of their use as beasts of burden, they could easily become extinct. They have been regarded so much as a poor relation of the horse that nobody here seems to have taken the trouble to make a study of them or supply instruction and information.

Lady Swinfen’s feeling for animals alone qualifies her to write a book about them. She has had the interest and enthusiasm to do a tremendous amount of research into the history of donkeys; she has had the practical experience gained from her breeding establishment to write the sections on the care and management of donkeys; and she has the great love of donkeys which makes her such an ardent and prominent campaigner to get their conditions bettered and their worth recognized. She shows that they are wonderful pets, less expensive and more houseable than horses, and who can deny that many of our great horsemen, on the flat and over jumps, and in the hunting field, gained their early knowledge of riding astride a donkey?

Although the association between man and the working-type horse is nearly over, interest in the sporting and recreational spheres is as great as ever. Averil Swinfen, with the production of her book, fills a gap in Irish literature about this most neglected member of the equine family.

VincentO’Brien

Preface & Acknowledgments to the Lilliput Edition

AFTER CLOSING the Donkey Stud in the mid-eighties, and moving house elsewhere, more than once, I had to board out my remaining animals. I would now like to thank many friends for assistance at that time. Also, much gratitude is due to all those persons in various places who helped in many ways over the years to care for my unique and much valued Twinnies, Ome and Omi (see Chapter Two).

In this edition, each chapter has had minor revisions and corrections, and Chapters One, Two, Three, Six and Nine have been substantially reworked to incorporate new material. Chapter Twenty is entirely new. Thus, some anachronisms may appear in the sections that have not been significantly changed. While I was updating this book, I received help from the following people, in addition to those mentioned in the Preface and Acknowledgments to the 1969 edition.

Father Ignatius Fennessy, OFM, the Franciscan Librarian in Killiney, furnished me with much information from his authoritative research. I am most grateful to him for his kindness. My thanks also to Seamus and Caroline Corballis for added and helpful material.

Chiefly I owe a more personal debt to Dr Tony Sweeney, a long-time friend, whose unfailing assistance has been immediately available at all times—many, many thanks for invaluable contributions.

Also I have to thank my efficient editor, Jennifer Smith, whose help and advice has been so important in the preparation of this edition. To Gillian Somerville-Large, my grateful appreciation for her generous co-operation, not only for typing these pages, but giving me much aid in checking and assembling them.

It was a joy to learn of a recent distinction accorded Vincent O’Brien, who so kindly wrote the foreword to the first edition. Ten years into his retirement, the memory of his achievements still burns brightly, as was shown when he headed the readers’ poll conducted by TheRacingPost to choose the top hundred turf celebrities.

As for my late husband, Carol, his steadfast support was always my mainstay in this highly unusual adventure.

AverilSwinfen

CountyKilkenny,Ireland,2004

Preface & Acknowledgments to the 1969 Edition

ITHINK THAT IF, before I had started this book, I had read the suggestion made by Rev. J.P. Mahaffy, DD CVO, that to write a monograph about the ass one ‘must not only be a zoologist, but a historian, and also even a psychologist’, I would never have dared to put pen to paper, having absolutely no pretensions to any of these accomplishments. Indeed, I have nothing to excuse me at all, save a deep affection and respect for these animals and better opportunities than most people to observe them, and the hope that anything that tends to increase interest in and regard for them will equally tend to reduce the indignities and suffering to which they have for so long been subject.

Not that they have been entirely without protectors. The Irish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals has done, and continues to do, magnificent work for the donkey, no less than for other animals, and no praise is too great for it.

I am only too conscious that there are many matters of great interest concerning asses that I have omitted, some because they have been more than adequately dealt with by previous writers, and others because they require a technical knowledge that I do not possess.

The broken-coloured breeding theory put forward in this book is my own untutored idea and if those more learned than I should be sufficiently interested to investigate further, it would indeed be of great interest to us donkey lovers.

In Ireland the older word ‘ass’ is used throughout the countryside in preference to the word ‘donkey’. This latter word used to be pronounced to rhyme with ‘monkey’. It is derived from the word ‘dun’ meaning a brownish-coloured horse; the suffix k-ey is a double diminutive, making it a little little horse. It seems to have been a late eighteenth-century Celtic and English word. In my writing I have not kept to either word, using each indiscriminately as it came to mind. The term ‘broken-coloured’ I have used to incorporate piebald, skewbald and any other decisively marked ass of two or more colours.

Though County Clare is now my home and holds my heart, as it has that of others of us in past generations who have been connected with it, the happy memories of childhood, however, never allow me to forget the county of Cork, one of the loveliest counties in Ireland and the home of my family for generations.

So many people have been kind enough to show interest and give assistance towards putting this book together that it is impossible to thank them all individually. Some have given generously of their time and skill in unearthing for me information that I had difficulty in finding, others very kindly wrote to me volunteering notes, tales and pieces of information: all showed boundless goodwill. I can but assure them collectively of my gratitude.

There are some, however, whose help was quite invaluable and to them I tender my sincere thanks: Desmond J. Clarke, MA FLAI, Librarian of the Royal Dublin Society; Alan R. Eager, FLAI, Assistant Librarian of the Royal Dublin Society; Michael Flanagan, FLAI, Librarian of the Clare County Library, Ennis, and his assistants; Dr J.S. Jackson, Keeper of the Natural History Division of the National Museum of Ireland; and Dr Thomas Wall of the Irish Folklore Commission.

I am indebted to the staff of the Royal Irish Academy and of The National Library, Dublin, and Miss Hynes of The Sweeney Memorial Library, Kilkee, County Clare, for their assistance; Mrs Maureen Kenny, BA, of Kenny’s Bookshop, Galway, for her constant help and encouragement; Mrs Sonia Kelly for kind assistance in typing and stringing together my earlier notes; Morgan O’Loughlin, MVB MRCVS, for reading and giving me his valued advice on Chapter Nine (‘Care’).

My thanks are also due to LifeMagazine and Ireland’sOwn for so kindly giving me permission to include in this book excerpts from their publications.

When we started our stud here, we were unaware of the existence of any other donkey breeders and we have always been sincerely grateful for all that has been done to help us by our local vets. Their professional etiquette requires that I should not name them but, even though they remain anonymous, I wish to thank them wholeheartedly.

I am grateful too to our donkey girls and the members of our establishment for their understanding and willing assistance in freeing me to pursue my donkey lore.

I greatly appreciate the kind assistance I have received from Countess von der Schulenburg, in the work she has done and the care she has taken over the final manuscript.

As for my husband, his unfailing encouragement and help have been my main support along the devious pathways of the donkey trail which we have travelled together.

Finally, I would like to thank our many ‘donkey friends’ in County Clare and elsewhere for much encouragement, help and genuine interest shown in our stud adventurings, hoping that we can continue to further the interests of the donkey with the same happiness and gaiety.

AverilSwinfen

CountyClare,Ireland,1969

Introduction

THERE HAVE BEEN MANY changes in the life of the Irish donkey since this book was first published in 1969 and reissued in 1975. In those not-so-distant days the donkey was still an integral part of the Irish rural scene. Now it has almost disappeared. For while there are a number of them kept as pets, the donkey as a working animal is seldom seen, except occasionally in remote rural areas—no more carting milk-churns to the creamery, toiling on the turf bogs, hauling seaweed from the seashore, and divers other labours, since today mechanization has taken over these tasks.

The intervening years have not all been happy ones for our long-eared friends. Those kept as pets are well nurtured and many have developed into splendid animals. Others have experienced the disregard too often meted out to creatures that lack commercial value and have suffered neglect and cruelty. However, since the advent of donkey sanctuaries in the country, notably at Liscarroll, County Cork, and the Richard Martin Restfields in counties Wicklow and Donegal, these sorrowful animals are rescued to be nursed with affectionate attention. Later, when recovered, some are leased out into suitable homes. Those that have fallen into the hands of callous dealers and been dispatched overseas seldom meet other than a pitiless end. There remain some fine donkeys in Ireland, but not ‘going for a song’ as in days gone by.

In September 1970, together with the late Mrs Murray Mitchell and other enthusiastic supporters, we founded the Irish Donkey Society (IDS) at a gathering in Limerick, having previously advertised in the press for any interested persons to join us there.

The main aims of the Society were to raise the status of the animal and to stamp out cruelty and ill treatment. Also, as more and more donkeys were participating in agricultural shows, it was to act as a governing body to which show committees could refer for the drawing up of rules and other matters, including the desired conformation points upon which the donkeys were to be judged. Happily, within two years donkeys were permitted to join the élite of our domestic animals at the renowned Royal Dublin Society Horse Show, where they continue to disport themselves with distinction.

Simultaneously in 1970, affairs moved ahead at our stud at Spanish Point, County Clare, for with the help of Bord Fáilte, our venture was officially opened as a tourist attraction by Dr Patrick Hillery, the Minister of External Affairs. It provided conducted tours of the farm, rides and trap drives for children, a snack room, and a donkey souvenir shop. Also on the programme were short safari treks into the Burren. This, combined with visiting mares for service to our various coloured stallions, led to busy times after the previous five years, which had been relatively relaxed.

A curious addition to our stud, though not born there, was Paddy Medina, a grey gelding with short extra legs, complete with hooves, attached to the inner side of both natural forelegs. These were not monstrosities, but reversions to features of early equine ancestors. Another novel acquisition was Firefly, a mule who when suspicious of any unusual activities afoot, would sit for long spells in a dog-like pose. A most treasured donkey is 34-year-old Susie, an early emigrant from our stud to my Humphreys cousins in Somerset, where she has helped to raise the family.

As our stock increased we sold some to commendable persons, both at home and abroad, always in pairs or as a companion to another animal. Those that were deemed suitable and were fittingly handled we donated to homes for handicapped children.

I found that the years ahead were monopolized by activities associated with the Irish donkey: I edited the Irish Donkey Society magazine, Assile; periodically contributed to its counterparts in other countries; and wrote DonkeysGalore.

Early in the 1980s, after family illness, bereavement, and a subsequent move of the stud to nearby Kilfenora, it became impracticable to keep the enterprise afloat. A sad time for all concerned, for it was unique of its kind in Ireland. Arguably there was not another collection of Equusasinus anywhere, wild or domestic, comprising the variety of colours, markings and other characteristics of their original species as were incorporated in our herd of more than one hundred animals at the culmination of almost twenty years agrowing.

Visits to donkey locations in other countries proved most enlightening. It was a joy to see again stock we had exported, meet their owners and other donkey enthusiasts from as far afield as Australia, Fiji, the USA, and other places nearer home, while exchanging the latest donkey news.

A truly exceptional experience was a visit in 1981 to Hai Bar, the Biblical Wildlife Reserve in Israel, 40 km north of Eilat. Having arrived there alone early one morning, I was brought by a game warden in a small tractor-trailer to see the wild asses. Of the two resident herds, one was of the Somali breed (Equussomaliensis) and the other species an Asiatic wild ass (Equusonager). These handsome animals, while living in close proximity, remain in separate herds; the mares, guarded by their stallions, breed only among their own species. I was permitted to wander and photograph close by and it was fascinating to see their specific markings, colourings, and general formation and to note which distinctive features are inherited in our domestic Irish donkeys.

Set up by Dr Elisabeth D. Svendsen MBE, The Donkey Sanctuary, which manages the centre in Liscarroll under its director Paddy Barrett, as efficient as he is popular, incorporated the International Donkey Protection Trust. While this trust confines its splendid work to projects outside Britain and Ireland, any international communication with the Irish donkey is to be welcomed and supported.

It is difficult to assess the present number of donkeys in Ireland as they are not registered; however, the interest in those that subsist continues. And, with the constant supervision of the various sanctuaries and the Irish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Irish donkey has every hope of remaining one of the most cherished of its kind.

I

THE DONKEY IN IRELAND

1. Origins

THE IRISH ASS. What sort of image does that bring to mind? Certainly not that of a large, swift-footed, vari-coloured creature, and yet there is no doubt that the ancestors of our present domestic ass were so described.

The wild asses of Africa are held by some authorities to be the source of our present domestic ass, especially those that came from Nubia, Abyssinia, and other parts of North Africa east of the Nile. They are zoologically known as Equusasinustaeniopus, the final word being applied to them because in some of the species the lower limbs show dark stripe-like markings. (Many of our contemporary asses still produce these horizontal stripes on their legs.) Most of these asses had the dorsal stripe along the ridge of the back, continuing into the mane and tail, and also a distinct cross stripe over the shoulder, and were in colour a mouse-grey—in fact, the colour that we associate with our more ordinary domestic ass of today. The Somali wild ass, Equussomaliensis, which still survives under careful protection, differed from its previously described neighbour by being greyer in colour, more a stone grey, having only a slight indication of a dorsal stripe, more numerous black markings on the legs and, above all, a complete absence of the cross stripe over the shoulders.

Though these wild asses were larger and stronger looking than our average Irish ass, we can still find a good mixture of their colourings and markings amongst our present-day animals. Yet, if we assume that the African wild ass is the ancestor of our modern one, we dismiss too lightly the Asiatic wild asses, especially the onager family, Equusonager,onagerindicus and hemippus, which roamed the plains of Asia, western India, Tibet, Afghanistan, Persia, Syria, and were even heard of as far as China.

They differed so slightly from each other that they can be described together. All being extremely fleet-footed, with smaller ears than the African wild asses, they stood between eleven and twelve hands high. Their colours were white and chestnut (brownish-yellow). The white ones occasionally had yellow blotches on their sides and neck, and the dorsal stripe was dark brown of varying breadth, with sometimes a white edge to it. The mane stood erect and the tail had short hairs at the base that grew longer and blacker towards the end, so that it appeared tufted.

The chestnut ones seem to have varied in shades with darker dorsal stripes of the same colourings, and some animals from each colour group showed a shoulder stripe and faint bars on the legs. William Ridgeway relates that in Syria these were often referred to erroneously as ‘wild mules’ in spite of the fact that they bred freely. Frederick Zeuner calls all the Asiatic wild asses ‘half-asses’ or ‘hemiones’ (from the Greek, hemi=half, oinos=one). All had a most strident bray. Other interesting animals included in the category of Asiatic wild asses are the kiangs of Central Asia, often called ‘neither horse nor ass’, looking more like a mixture of a horse and an ass than does a mule or jennet. The kiangs of Tibet and Mongolia seldom lived at an altitude lower than 10,000 feet. They stood over thirteen hands high and differed from the onagers in their colouring, which ranged from chestnut to bay (reddish-brown) and sandy fawn on the upper parts of their bodies, with off-white underparts and with a very narrow brown dorsal stripe. Their hindquarters were more developed in length and strength than those of onagers and they had different voices.

That there were wild asses in Libya in the fourth century BCE has been mentioned by Herodotus in TheHistories, and it seems that they continued to exist there until mediaeval times. Frederick Zeuner writes that the North African wild asses (which must have included the Libyan wild asses) were last seen in the Atlas Mountains and did not survive the Roman period. These, he states, were depicted on rock pictures and Roman mosaics, but as he gives no description of them, and I have not been able to find one elsewhere, I do not know whether or not they were a different species, and if so whether they were indigenous to North Africa or just migrants. I found this description in an account of the asses used in mule breeding in the USA published by a Mr Killgore at the end of the nineteenth century:

In the province of Catalonia in old Spain, there exists a race of asses, bred with great care for many centuries, having been introduced into that country by the Moors at the time of their conquest of that Kingdom (in the eighth century). They are black in colour, with white or mealy muzzles, and whitish or greyish bellies, varying but little in form, but greatly in size.

In present-day North Africa the majority of asses are very like our familiar mouse-coloured animal though much smaller. The larger dark brown to black animals with grey or grey flecked bellies are also present, and occasionally the light chestnut or greyish-white ones lacking the cross stripes are to be seen.

However, in describing these wild asses, it will be noticed that there is no mention of certain colours, such as black, roans and broken colours. This makes us wonder how they quite liberally made their appearance into our present-day ass family. Zoologists are unanimous in regarding their colouring and stripes as being among the principal indications that the African and Asiatic wild asses are separate breeds. It seems fairly obvious that the descendants of these animals must have met somewhere to produce the present colours. Where and how this meeting took place is our problem.

Taking into account all the asses we have in Ireland today of different colours, markings and other characteristics, it may be assumed that over the centuries all the different kinds intermingled through transcontinental trade routes. The traders themselves used asses for transport and these asses were hired at the different places that the caravans passed through en route. The Jewish tractate, BabaMesia, testifies to this when it lays down the laws for the hiring of asses and ass drivers by contract, and regulates their foods and maximum loads. It is interesting to note that the animals from Lycaonia, now a part of modern Turkey, were the strongest of all breeds and thus best for long journeys.

These ancient trade routes wound their way across Asia from Nanking in eastern China to the Phoenician city of Tyre, and from there they continued either through Egypt and Libya over North Africa on the south or through Turkey and Greece on the north of the Mediterranean into Europe, and so over the years to Britain and Ireland, thus travelling through the habitats of most known Asiatic ass herds.

The routes that the African asses took are less well known. They certainly travelled westwards and then northwards across Africa to the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar). This can be deduced from the appearance of their descendants when we meet them in the countries traversed. We hear from Herodotus that

there is a great belt of sand, stretching from Thebes in Egypt [about 500 miles from the Mediterranean] to the Pillars of Hercules. Along this belt, separated from one another by about ten days’ journey, are little hills formed of lumps of salt, and from the top of each gushes a spring of cold, sweet water. Men live in the neighbourhood of these springs.

He also tells us that a Libyan tribe, who lived in a place that is now called Fezzan in Tripolitania, chased the holemen or troglodyte Ethiopians (Abyssinians) in horse-drawn chariots along that great desert belt. This indicates that from ancient times there must have been constant communication across the Nile between northeast Africa, the home of the African wild ass, and the Mediterranean, other than through Egyptian coastal routes. Before entering Europe via Spain and Italy, one must have encountered the North African wild ass whose existence we know of but whose description is based solely on the information from Mr Killgore.

Having eventually reached Spain by one way or another, these animals found a welcome and so with care developed into an excellent breed. Their offspring quite definitely found its way to Ireland, showing individual characteristics from indigenous sources, or combining them, but finally degenerating through neglect and inbreeding.

In England donkeys were known in the tenth century, for James Greenwood in Wild Sports of the World says that, during the time of Ethelred, the donkey is mentioned as a costly animal and even in the time of Elizabeth I it was considered to be as valuable as a well-bred horse.