Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

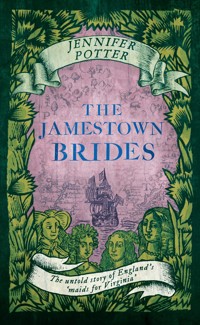

The extraordinary story of the British women who made the perilous journey to Jamestown, Virginia, to become wives for tobacco planters in the New Colony. In 1621, fifty-six English women crossed the Atlantic in response to the Virginia Company of London's call for maids 'young and uncorrupt' to make wives for the planters of its new colony in Virginia. The English had settled there just fourteen years previously and the company hoped to root its unruly menfolk to the land with ties of family and children. While the women travelled of their own accord, the company was in effect selling them at a profit for a bride price of 150 lbs of tobacco for each woman sold. The rewards would flow to investors in the near-bankrupt company. But what did the women want from the enterprise? Why did they agree to make the dangerous crossing to a wild and dangerous land, where six out of seven European settlers died within their first few years - from dysentery, typhoid, salt water poisoning and periodic skirmishes with the native population? And what happened to them in the end? Delving into company records and original sources on both sides of the Atlantic, Jennifer Potter tracks the women's footsteps from their homes in England to their new lives in Virginia. Giving voice to these forgotten women of America's early history, she triumphantly invites the reader to journey alongside the brides as they travel into a perilous and uncertain future.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 604

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE JAMESTOWN BRIDES

Jennifer Potter is the author of four novels and six works of non-fiction, including The Rose, A True History;Seven Flowers And How They Shaped Our World; and Strange Blooms, The Curious Lives and Adventures of the John Tradescants. A longtime reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement and an accredited Royal Literary Fund (RLF) Consultant Fellow, she currently runs writing workshops for students and staff at British universities and was recently appointed one of the first RLF Writing Fellows at the British Library.

‘I love this kind of historical writing, with the stitching showing… Engaged and thoughtful, Potter has given her women an existence they would recognise.’ Lucy Moore, Literary Review

‘An evocative and painstakingly researched account of these early female settlers, who have lacked a voice, an identity, even a name, until now. From 400 years ago, they step from these pages and speak to us.’ Hilary Davies, ‘Books of the Year’, The Tablet

‘Potter tells the story using a rich range of sources — pamphlets, ballads, sermons — and travels to flesh out gaps… She writes well and hauntingly, of women “penned like chickens in the gloom”, of their shock on arrival at a tiny, dilapidated Virginian town thousands of miles from the English capital.’ The Times

‘Potter weaves a compelling narrative, and her use of archival material is top notch… A real pleasure to read.’ BBC History Magazine

‘With extraordinary scholarship and painstaking use of contemporary texts Potter succeeds in her professed task of bearing witness to the lives of young women unknown to history… Full of sensational material.’ Times Literary Supplement

Also by Jennifer Potter

NON-FICTION

Seven Flowers

The Rose: A True History

Strange Blooms: The Curious Lives and Adventures of the John Tradescants

Lost Gardens

Secret Gardens

FICTION

The Angel Cantata

After Breathless

The Long Lost Journey

The Taking of Agnès

TheJamestownBrides

The Bartered Wivesof the New World

Jennifer Potter

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Jennifer Potter, 2018

The moral right of Jennifer Potter to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78239-915-5

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-916-2

Map on p. 197 by Jeff Edwards

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Chris and Lynn with love

and special thanks to Martha W. McCartney,Helen C. Rountree and Beverly A. Straube.

Contents

PREFACE: Witness

PART ONE:England and its Virginian Colony

CHAPTER 1: The Marmaduke Maids

CHAPTER 2: The Warwick Women

CHAPTER 3: A Woman’s Place

CHAPTER 4: Point of Departure

CHAPTER 5: Of Hogs and Women

CHAPTER 6: La Belle Sauvage

CHAPTER 7: Maids to the Rescue

INTERMEZZO: Maidens’ Voyage

CHAPTER 8: When Stormie Winds do Blow

CHAPTER 9: Land ho!

PART TWO: Virginia

CHAPTER 10: Arrival at Jamestown

CHAPTER 11: The Choosing

CHAPTER 12: Dispersal

CHAPTER 13: Catastrophe

CHAPTER 14: The End of the Affair

CHAPTER 15: The Crossbow Maker’s Sister

CHAPTER 16: The Planter’s Wife

CHAPTER 17: The Cordwainer’s Daughter

CHAPTER 18: Captured by Indians

ENDNOTE: Return to Jamestown

APPENDIX: A List of the Maids

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

List of Illustrations

Index

Wenceslaus Hollar, 1643

I looked at that wife, and of a sudden, the anger in my heart melted away. It was a wilderness vast and dreadful to which she had come. The mighty stream, the towering forests, the black skies and deafening thunder, the wild cries of bird and beast, the savages, uncouth and terrible, – for a moment I saw my world as the woman at my feet must see it, strange, wild, and menacing, an evil land, the other side of the moon.

Mary Johnston, To Have and To Hold

PREFACE

Witness

In the late summer and early autumn of 1621, a succession of ships set sail from England bound for Jamestown, Virginia. On board were fifty-six young women of certified good character and proven skills, hand-picked by the Virginia Company of London to make wives for the planters of its fledgling colony.1 The oldest was twenty-eight (or so she claimed) and the youngest barely sixteen. All were reputedly young, handsome and honestly brought up, unlike the prostitutes and vagrant children swept off the streets of London in previous years and transported to the colony as cheap labour.

The Virginia Company’s aim in shipping the women to Virginia was that of money men everywhere: to generate a profit by bringing merchantable goods to market. Since King James had abruptly suspended the Virginia lotteries on which the colony depended for funds, the company’s coffers were bare. Importing would-be brides was one of four moneymaking schemes designed to keep the company afloat, and its leaders in London hoped to ensure the colony’s long-term viability by rooting the unruly settlers to the land with ties of family and children. While the women travelled of their own free will, the company had set a bride price of 150lbs of tobacco for each woman sold into marriage, which represented a healthy return for individual investors. These were businessmen, after all, doing what they did best: making money.

But the women – what did they want from the enterprise? Why did they agree to venture across the seas to a wild and heathen land where life was hard and mortality rates were catastrophic? Had anyone whispered a word to them about the dangers they faced, or warned them how slim their chances of survival really were?

The Jamestown Brides sets out to tell the women’s story: who they were, what sort of lives they led before falling into the Virginia Company’s net, the hopes and fears that propelled them across the Atlantic, and what happened to them when they reached their journey’s end. I have stuck as doggedly as I am able to what the ‘evidence’ tells us, but the record is worn as thin as a vagrant’s coat, requiring a bold leap of the imagination to appreciate from the inside the shock of transitioning from one life to another, made all the harder by the four centuries that separate then from now.

Considered a mere footnote to Virginia’s colonial history, the story of the ‘maids for Virginia’ first came to me in Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, where I was researching Strange Blooms, a dual biography of John Tradescant and his son (also called John), gardeners to the Stuart kings and early collectors of plants and curiosities. Distracted by guides in eighteenth-century costume who were visiting the library to check their facts or simply to escape the tourists, I chanced across David Ransome’s scholarly article, ‘Wives for Virginia, 1621’.2 The story of these women shipped thousands of miles across the Atlantic to procure husbands has stayed with me ever since for reasons that are only partly personal. Then soon to be divorced myself, I could also be said to be looking for a husband, but how far would I travel to find one? (Answer: not far enough to find one.) Beyond that, I wondered what combination of faith, hope, courage, curiosity or just plain desperation might encourage me or anyone else – at any time – to journey into the unknown.

The starting point for my researches was a series of remarkable lists that survive at Magdalene College, Cambridge, among the papers of Nicholas Ferrar, a London merchant closely involved with the Virginia Company who would later retreat with his extended family to found an informal Anglican community at Little Gidding in the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Intended as a kind of sales catalogue for prospective husbands, the lists record the women’s personal histories: name, age, marital status, birthplace, parentage, father’s occupation, domestic skills, guarantors and testimonials from their elders and betters. Dry as they are, lists such as these quickly come alive as you make connections, chase after hares, interrogate possibilities, scramble into and out of dead ends like the ‘Kremlinologists’ identified by the Virginian historian Cary Carson – ‘decoders of elusive clues’ from the few surviving scraps of evidence, much of it buried underground.3

The Virginia Company’s council had every right to take pride in the human cargo they had assembled at East Cowes on the Isle of Wight and later at Gravesend. Some one in six were the daughters of gentry or claimed gentry relatives, while the rest presented a microcosm of ‘middling’ England, with fathers, brothers, uncles working in respectable trades. They came recommended by the great and good of the City of London or by company investors and employees, from the lowliest porter to Sir Edwin Sandys himself, the effective leader of the Virginia Company and chief architect of the scheme to bring brides to the colony.

One of the maids jumped ship on the Isle of Wight, but miraculously the rest survived the Atlantic crossing and arrived in good health. A few were married before the ships left Jamestown, so we are told, but a little over three months later an Indian attack wiped out between a quarter and a third of the English colony. For the word purists among us, descendants of Virginia’s indigenous people continue to call themselves Indians – and so I shall use the term throughout this book – but you must be careful how you refer to the events of that cataclysmic day. At the time it was invariably labelled a ‘massacre’, later an ‘uprising’ and now simply an ‘attack’ or the ‘Great Assault’, as a way of sharing responsibility for what happened, after fifteen years of concerted land grabs by English settlers and barbaric acts committed by both sides.

Some of the Jamestown brides died in the slaughter, others clung tenaciously to life. Lists of the living and the dead compiled soon after the attack and two later censuses allow us to track what happened to around one third of the Jamestown brides, who also appear fleetingly in court records and the minutes of Virginia’s general assemblies, held from 1619. However brief and apparently inconsequential, such records throw up snippets of everyday life: malicious gossip, misdemeanours, fraudulent land registrations and squabbles over property, the stuff of life that illuminates what became of the women and the kind of men they chose to marry.

In retelling the women’s stories, I am trying to experience life as they found it and to participate in the choices and decisions they made. Inevitably this means slipping myself into the narrative, as unobtrusively as possible, especially when I go looking for the women on the streets of London, in the backwaters of rural England and the Virginian swamps and settlements to which they scattered. The histories I enjoy take me back into the past but also bring the past into the present, however dislocating the effect. And so I found myself sifting through the detritus of material culture, the post holes and broken pottery shards of Carson’s Kremlinologists, looking for sites which the women may have seen and objects they may have held in their hands. I found them too, always with a heady rush of recognition: bodkins of silver and brass excavated at Jordan’s Point on the Upper James where one of the brides settled, fragments of clay milk pans made by a potter known to another of the women, although she never found herself an English husband; hers is one of the most unsettling of all the women’s stories.

No letter or journal survives from any of these women, nor should we expect any to surface. While girls from the middling classes might be taught to read along with sewing and knitting, writing was a skill generally reserved for boys and for the children (boys and girls) of the upper gentry or families exposed to humanist education. The task I have therefore set myself is to bear witness to the lives and stories of these women, whose voices have left no trace in the historical record. ‘I WILL BE HER WITNESS’ is how the narrator of Joan Didion’s A Book of Common Prayer begins her story of the decline and fall of one Charlotte Douglas, who dreamed her life and died, hopeful, in the fictional Central American republic of Boca Grande. The story I am telling is fact not fiction, but like Didion’s narrator I struggle to make sense of what happened.

Much of the book’s textual detail comes from listening to the ‘chatter’ of the times: the sardonic musings of social commentator John Chamberlain; the nostalgic antiquarian John Stow writing about a London that was changing before his eyes; Virginia Company records, which you must read between the lines in order to disentangle factional truths and falsehoods; the bombastic but always lively writings of Captain John Smith on Virginia and seafaring topics; accounts and letters home from a variety of early settlers, whose viewpoints veer from the disaffected to the wildly propagandist; and one of the richest sources of all, the babble of voices from the street contained in contemporary ballads, once derided as a historical source but now valued as social texts.

My book falls naturally into two halves, divided partly by geography and partly by chronology. Part One, ‘England and its Virginian Colony’, tells the women’s stories up to the moment they boarded their ships at Cowes and Gravesend. Early chapters delve into their social, economic and geographical backgrounds, grouping them according to the ships by which they sailed to Virginia. Crucially, this part looks also at how it felt to be a woman in early modern England. We need to know where the women came from, literally and metaphorically, to judge how far they travelled. The focus of Part One then switches to the Virginia Company’s colonization of North America, refracting Virginia’s early history through the experience of largely female settlers, although Chapter 6, ‘La Belle Sauvage’, examines the parallel narrative of Pocahontas’s marriage to English settler John Rolfe, and the perplexing fate of the Virginia Indian women who accompanied the Rolfes to England in 1616.

A short ‘Intermezzo’ carries the women across the Atlantic and tacks with them slowly up the James River to Jamestown, where they arrive in the winter of 1621.

Part Two, ‘Virginia’, takes the story forward, setting out as forensically as I am able how the colony will have appeared to these young women fresh from England, and how they settled into their new lives. Here lies the heart of the book, which also provides a fresh perspective on the Indian attack and its aftermath. Where did the women stay? How did they choose their husbands? Where did they go and how did they adapt to their new lives? Who lived and who died? What happened to those who never married? Did investors in the scheme ever reap the rewards they were promised? These are some of the questions I try to answer as honestly as I can, looking also at the Virginia Company’s inevitable decline and fall. Chapters 15 to 18 pick up the lives of four women who survived through the 1620s, three who married and one who was captured by the Indians. Tracking these four women through the records and on the ground has been a joy, linking the very English landscapes of their childhoods to the creeks and inlets of tidewater Virginia where they made their homes. Place matters in this book, as you will see.

In my acknowledgements I pay tribute to the enormous help I have received from many people and institutions in the UK and in Virginia. Here I would like to thank three women in particular who have generously shared with me their unique insights and helped to guide my researches in Virginia: historian Martha McCartney, anthropologist and cultural historian Helen Rountree, and curator Beverly (Bly) Straube. This is a book written by a woman about women’s experiences, aided by women. Men have helped too, of course. I think of archaeologist Nicholas Luccketti giving up a bright but bitter Sunday morning to walk me over the ground of Martin’s Hundred, and riverkeeper Jamie Brunkow taking me from Jamestown down to Burwell’s Bay and back again, to experience the river as the women will have done, from the water. Thank you all: without your help this would be a far slimmer book.

Historians are taught not to judge the past by the standards of today, fair enough, but the fundamental question I am asking demands the exercise of judgement. I leave this task with you in the hope that you may find your own answers in the pages that follow. Were these women the victims of a patriarchal society, shipped overseas to serve the interests of others: investors who stood to gain from their ‘sale’, company officials who wished to tame male colonists with the carrot of female company, planters looking for female skills to aid their colonizing endeavours, English families wishing to dispose of unmarried daughters on the cheap? Or were they adventurers in the truest sense, women prepared to invest their persons rather than their purses in the New World?

A note on the text

Most quotations from primary sources retain the original spelling, although I have substituted ‘u’ for ‘v’ and ‘j’ for ‘i’ where relevant, and supplied missing letters from some abbreviations. Dates generally follow the old Julian calendar, realigned to start each new year on 1 January. Despite having originally intended to write this book without using notes, I believe that any claim to ‘truth’ must be open to challenge. I therefore supply references exclusively to indicate my sources; the text can happily be read without them. For readers unfamiliar with England’s pre-decimal currency, twelve pennies made one shilling and twenty shillings one pound sterling, expressed as £ s. d. As well as the ‘£’ sign, pounds could also be abbreviated to ‘li’ from the Latin word, ‘libra’. In 1620s Virginia, tobacco was the prevailing currency: one pound in weight of best Virginia tobacco was then officially valued at three shillings, or £19.73 at today’s values.

PART ONE

England and its Virginian Colony

Come all you very merry London Girls,that are disposed to Travel,Here is a Voyage now at hand,will save your feet from gravel,If you have shooes you need not fearfor wearing out the LeatherFor why you shall on shipboard go,like Loving Rogues together,Some are already gone beforethe rest must after followThen come away and do not stayYour guide shal be Apollo.

Lawrence Price, ‘The Maydens of Londons brave adventures, / OR, / A Boon Voyage intended for the Sea’, London, printed for Francis Grove on Snow-hill, 1623–1661

CHAPTER ONE

The Marmaduke Maids

Some time after Sunday 12 August 1621, thirteen young women gathered beside the burgeoning wharves and storehouses at East Cowes on the Isle of Wight, waiting for a lighterman to row them out to the Marmaduke anchored in the roads.1 Already a month into their journey, they had travelled by boat from London to Gravesend and after a short stay had continued overland to Portsmouth then by boat across the Solent to Cowes on the island’s northern coast.2 The Virginia Company had commissioned the Marmaduke’s master, John Dennis, to pick up passengers and goods from the Isle of Wight, and here the women had stayed until the boat was loaded and the winds and the tide turned in their favour.

The hand-picked women travelled without family, apparently of their own volition, in response to the company’s call for ‘maydes for Virginia’ – English women ‘young, handsome and honestlie educated’ willing to cross the Atlantic to marry planters in its colony of Virginia, then less than fifteen years old.3 Promised a free choice of husband, the women doubtless remained ignorant of the financial nature of the operation: that they formed part of a ‘magazine’ or trading enterprise designed to bring much needed cash from individual investors to replenish the company’s now empty coffers.

Among those whose fortunes we shall track is Catherine Finch from the small rural parish of Marden in Herefordshire, where she was baptized in the church of St Mary the Virgin, perched beside the sluggish River Lugg in a broad flood plain surrounded by gently undulating farmland. The long-distance footpath across the Welsh Marches runs through the straggling village, which remains deeply agricultural to this day, its old-world charm dislocated by shimmering rivers of polytunnels protecting the soft-fruit crops of the region’s thriving agribusinesses and refrigerated lorries thundering through its narrow country lanes.

As parish records for Marden survive only from 1616, it has not been possible to check the age that Catherine declared to the Virginia Company (twenty-three in 1621), but you can still touch the fourteenth-century sandstone font where she was baptized and admire the fine brass plate commemorating the ‘Pietie and Virtues’ of a gentlewoman from Catherine’s time: Dame Margaret Chute, who died on 9 June 1614 following complications in childbirth, the day after her infant daughter, Frances.4 Clearly a member of the upper gentry, Dame Margaret is dressed in the court fashions favoured by Queen Anne of Denmark, wife of the Stuart King James: low neckline, tight bodice winged at the shoulders and pointed at the waist, cuffs and raised collar in expensive needlepoint lace, necklace of pearls and one visible dangling earring. Her children appear beside her, a surviving daughter dressed like a scaled-down version of her mother and the dead baby wearing a lace collar and bib over her swaddling clothes. The young Catherine will have seen the Chute family at church, seated according to their station in life, which placed her own family somewhere between the middle and the back.

From Marden, the orphaned Catherine Finch travelled to Westminster to live in service with her quarrelsome brother Erasmus Finch, crossbow maker to King James and later to King Charles I. Erasmus then lived on the less favoured ‘landside’ of the Strand, a wide thoroughfare connecting the two cities of London and Westminster where poor and middling sorts of people lived in tenements squeezed between the grander houses of aristocrats, courtiers and gentlemen’s lodgings. Two other brothers lived close by: Edward, described variously as a goldsmith and a locksmith, a little way east along the Strand in the parish of St Clement Danes, and John, also a crossbow maker, in St Martin’s Lane off the Strand, a winding thoroughfare running northwards from Charing Cross to the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields flanked by land only recently turned over to housing. Brother John would rise to be one of ten assistants in the newly formed Company of Gunmakers under Master Henry Rowland, the king’s master gunmaker, outranking Erasmus Finch, who appears among the commonality of ‘Skilful Artists’.5

One of Catherine’s companions on the Marmaduke was Audry (Adria) Hoare, a shoemaker’s daughter from the lace-making town of Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. Baptized on 25 August 1604 at the parish church of St Mary the Virgin, Audry was the youngest child of Thomas and Julyan Hoare, aged barely seventeen when she sailed, two years younger than the age she gave to the Virginia Company. She had at least four older siblings, three sisters (Joan, Agnes and Elizabeth) and brother Richard, apprenticed to a fustian dresser.6 Unlike many of her fellows, Audry Hoare had both parents still living when she was brought to the Virginia Company by her married eldest sister, Joane Childe, who was living in Blackfriars ‘down in the Lane neer the Catherne wheell’, which might refer to a tavern or to a tenement building.7 Stretching north from the Thames, this lively neighbourhood was popular with gentry and much favoured by players, musicians, composers and artists. Shakespeare was a shareholder in the small, indoor Blackfriars Theatre and even bought a substantial house here in 1613, which he bequeathed to his daughter Susannah on his death just a few years later.8

On the face of it, neither Catherine Finch nor Audry Hoare had an obvious reason to join the shipment of young women willing to risk their futures on finding a husband in the New World. Audry Hoare had close kin living in London and well connected relatives who might have helped her attract a husband: one of her first cousins was a merchant, Master Thomas Biling, and another an upholsterer in Cornwall. Catherine Finch enjoyed even more advantages. She lived with her brother, a craftsman with royal connections, in one of the capital’s most vibrant and fashionable neighbourhoods, within easy reach of the river and the open spaces of St Martin’s Field, and she had other family living nearby. Surely her chances of finding a husband were better than most? But all three brothers commended her to the Virginia Company, either because they wanted to rid themselves of responsibility for their unmarried sister, or because Catherine herself was more than willing to adventure her life overseas. Perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between: that through his royal connections or neighbourhood gossip Erasmus Finch caught wind of the company’s plan to ship marriageable women out to the colony and successfully convinced his sister to take up the challenge.

It is easy to see why a third Jamestown bride aboard the Marmaduke wished to travel to Virginia. Also considerably younger than the age she gave to the Virginia Company, Ann Jackson was bound for Martin’s Hundred, some ten miles downriver from Jamestown, to join her bricklayer brother John Jackson, who had represented the new settlement as one of its two burgesses in Virginia’s first general assembly held in 1619. Born within sight of Salisbury cathedral and baptized on 24 September 1604 in the parish church of Sarum St Martin, several years after two brothers, Ann Jackson came to the Virginia Company with the blessing of their father William, a man of ‘known honesty and conversaton’.

By the time Ann sailed, William Jackson had moved from Salisbury to Westminster and was living in one of the overcrowded tenements squeezed into dingy alleyways between the grand houses of Tuttle (Tothill) Street inhabited by the nobility.9 No mention is made of Ann’s mother so I can only assume she had died and that Ann was keeping house for her father, who was attracted like many others to the densely populated parish of St Margaret’s to serve the courtiers and bureaucrats of Westminster. Since his name does not appear in the various tax assessments for the parish, he was either subletting or judged too poor himself to contribute towards the upkeep of paupers, but as a gardener William Jackson will have found plenty of work tending the large gardens running north and south from Tuttle Street.10

The maids who sailed by the Marmaduke left England from East Cowes across the Medina estuary from Cowes Castle, sketched here by the Dutch artist Lambert Doomer.

While account books and ledgers can tell you the names of the passengers taken on board, they cannot tell you what those passengers were thinking, or how the women viewed their prospects as they waited for the flat-bottomed barge that would take them out to the Marmaduke.

Already one of their number had jumped ship: the widowed Joan Fletcher, at twenty-eight one of the oldest in the group and by all accounts the best connected, born into a prominent family in Cheshire and Staffordshire that included members of parliament, viscounts, a lord chancellor and even an earl. Her paternal uncle, Sir Ralph Egerton Knight, may be identified as one of two Ralph Egertons of Betley in Staffordshire, either ‘Radus [Ralph] Egerton de Betley, Armiger’, who married his relative Frances Egerton in January 1577, or their first-born son Radus, baptized at Betley three years later.11

Perhaps the widowed Joan Fletcher had taken fright at her companions or at the cramped conditions and undeniable hardships of travel in early seventeenth-century England. It can only have been a last-minute decision as the trunk containing her personal possessions was loaded onto the ship before she changed her mind, or had it changed for her.12 All we know is that she was ‘turned back’ at the Isle of Wight and her place taken by An[n] Buergen, who may have been of German or French origin since Buergen in all its variant spellings is not a local name.13

The ship’s master, John Dennis, carried with him a letter from the Virginia Company to the governor and council in Virginia, clearly written before Joan Fletcher’s hurried departure, as it includes among the ship’s passengers ‘one Widdow and eleven Maides for Wives for the people in Virginia, there hath beene especiall care had in the choise of them; for there hath not any one of them beene received but uppon good Comendacons, as by a noat herewth sent youe may perceive’.14 In fact thirteen women sailed on the Marmaduke as part of the bridal shipment, according to a second note written by Nicholas Ferrar, merchant and younger brother to John Ferrar, who was then deputy to the Virginia Company – in effect its chief administrator – and the Ferrars’ clerk, Tristram Conyam. The thirteen included eleven maids from the original dozen, Joan Fletcher’s replacement Ann Buergen, and Ursula Lawson, who was travelling with her kinsman Richard Pace and his wife, on their return to the colony.15 Just two of the Marmaduke women were Londoners born and bred: twenty-year-old Susan Binx, raised outside the City walls in St Sepulchre’s parish, and fifteen-year-old waterman’s daughter Jane Dier, the baby of the group, brought by her mother, who lived among the drunken Flemish refugees, seamen, madmen and pestering tenements of the riverside precinct of St Katharine’s by the Tower. The others were all born elsewhere.

Wherever their birthplace, most of the young women were living in London by the time they fell into the Virginia Company’s net, working in service with family members or respectable citizens who could vouch for their honesty and industry. As was usual for the times, a good many had lost either or both parents, but socially these women were far from society’s cast-offs. If we include Joan Fletcher among their number, as many as five of the original dozen were the daughters of gentlemen or counted gentlefolk among their relatives. The father of twenty-one-year-old Ann Harmer from Baldock in Hertfordshire was ‘a gentleman of good means now lyvinge’. Londoner Susan Binx had a widowed maternal aunt, Mistress Gardiner, a gentlewoman living near the Finches in the Strand. Margaret Bourdman’s maternal uncle was Sir John Gibson, knighted by King James in 1607 and holder of the patent to exploit alum in the North Riding of Yorkshire, a county he would later serve as sheriff.16 Lettice King could even lay claim to two gentry relatives. One was an uncle dwelling in London’s Charterhouse, then an almshouse for indigent gentlemen, soldiers or merchants, although he was later expelled for ‘misprision of treason’, a lesser form of treason or concealing the treachery of others.17 The second was her cousin once removed, Sir William Udall, in all likelihood the popular courtier Sir William Uvedale or Udall, who had recently been nominated by the Earl of Southampton as member of parliament for the Isle of Wight.18 Given Southampton’s involvement in Virginia Company affairs – he was soon to take over as treasurer – he may have been the conduit for Lettice King’s recruitment to the Jamestown brides.

While not of such elevated stock, the other Marmaduke maids had fathers, brothers, uncles or cousins who worked in respectable trades as saddlers, husbandmen, soldiers, wire drawers, grocers, printers, in addition to the merchants, gardeners, shoemakers, upholsterers, crossbow makers and fustian dressers already encountered. Even Jane Dier’s dead father could claim his place among Sir Thomas Overbury’s Characters, which painted the watermen as tellers of ‘strange newes, most commonly lyes… When he is upon the water, he is Fare-company: when he comes ashore, he mutinies; and contrarie to all other trades, is most surly to Gentlemen, when they tender payment.’19 Here was a microcosm of middling England under King James, independent tradesmen who worked for their living, trading with the products of their hands or with the skills in business or the professions for which they had trained.20

In putting together its prospectus for potential husbands, the Virginia Company took pains to enumerate the women’s accomplishments. Provenance alone was sufficient guarantee of worth for most of the gentry daughters among them, while skills listed for the lower-status women were generally of two sorts: robust, practical skills in housewifery on the one hand, and more refined needlework or knitting skills on the other. Despite her more advanced age (not in itself a handicap), husbandman’s daughter Allice Burges would have made a splendid planter’s wife: ‘She is skillfull in manie country works, she can brew, bake and make Malte etc.’ The same was said of another husbandman’s daughter, Ann Tanner from Chelmsford, who could ‘brew, and bake, make butter and cheese, and doe huswifery’, in addition to her ability to ‘Spinn and sewe in Blackworke’.

Another four Marmaduke maids had rarefied needlework skills: Cambridge-born Mary Ghibbs could make intricate bone lace, which involved weaving linen thread around bobbins of bone. Brought up in the household of a seamstress, gentleman’s daughter Ann Harmer ‘can doe all manner of workes [in] gold and silks’, while Audry Hoare could ‘doe plaine works and blackworks’ and make all manner of buttons. As well as working in ‘divers good services’, Susan Binx was able to knit and embroider in white- and blackwork, a skill she may have acquired from her wire-drawer father, since blackwork embroidery was sometimes embellished with gold or silver-gilt thread. But the fashion for blackwork was almost over, and it is hard to imagine that its delicate ornamentation would prove a selling point for a planter’s wife in Virginia.21

By the time the women reached the Isle of Wight, they will surely have got the measure of each other and begun to form natural alliances that would help them weather the long journey ahead. The man charged with seeing them safely aboard their ship was local merchant Robert Newland from nearby Newport, who had been largely responsible for bringing the Virginian trade to the island. It was Newland who had replaced Joan Fletcher with Ann Buergen, and given the delicate nature of his cargo, he will undoubtedly have wished to attend on them personally as they waited for the boat that would take them out to their ship, anchored in the choppy waters of the Solent.

Facing north towards the English coast, Cowes is a town in two parts – East and West Cowes – straddling the mouth of the River Medina. In Tudor times, ships had traded from Newport at the head of the estuary, but by 1575 a new customs house had brought maritime trade downriver to East Cowes, and now Newland was devoting his considerable energy to establishing a working port with storehouses and a quayside.22

He had come to the Virginia Company’s attention two years before the women left for Jamestown, recommended by Gabriel Barbor in a letter to Sir Edwin Sandys, who had just wrested control of the company from wealthy City merchant Sir Thomas Smythe.23 One of the overseers of the Virginia Lotteries, Barbor was personally connected to two of the women: Marmaduke maid Mary Ghibbs, and Fortune Taylor who sailed shortly afterwards on the Warwick.

Newland was, said Barbor, ‘an honest sufficient & a moste indevoring man for Virginia’, who could further the colony’s development by victualling the ships or providing manpower. Already he was ‘so well reported of’ by the Virginia Company of London’s sister Plymouth Company, among others, and had helped Captain Christopher Lawne establish a Virginian plantation along the James River in what would later become Isle of Wight County. Indeed, Newland was one of nine associates who had invested in Lawne’s plantation, earning praise as a ‘ventrous charitable marchant’.24 Newland would not only help prevent deserters from the company’s ships, promised Barbor, but would ‘victuall cheaper th[a]n Londoneres’, surely his chief attraction for a commercial company perennially short of funds.

Sandys and his deputy, John Ferrar, had clearly taken Barbor’s recommendation to heart and commissioned Newland to ship some 230 people and supplies by the Abigail from his base at East Cowes ‘for the more comodiousnes and for procuringe of people the better’.25 The operation was so successful that Newland was given five shares in the Virginia Company on condition that he did not sell them, recognizing the ‘extraordinary paines taken in their service in taking care of Shipping their people in the Abigaile at the Ile of Wight’.26

That was in early May 1621, just three months before the Marmaduke set sail from East Cowes and right at the start of the port’s brief decade of prosperity, when Robert Newland had a hand in much of the island’s trading activity. ‘All things were exported and imported at your heart’s desire,’ wrote the islander Sir John Oglander, recording the port’s rapid development from just three or four houses at Cowes to the magnificent sight of 300 ships riding at anchor in the roads, before European wars brought ‘poverty and complaint’ back to ‘our poor Island’ by the end of the decade.27

Although Newland drops out of the Virginia Company’s story from late 1622, when he received a commission to transport people to Virginia on the Plantacon and to proceed on a fishing voyage,28 he continued to play a leading role in island affairs as one of Newport’s chief burgesses, rising to mayor in 1629 and again for three months in 1636. Just one month after the Marmaduke sailed for Virginia, he was entrusted with the town’s ‘Comon Box to receave and accompt for all the towne rents revenues and proffitts’.29 But he was not considered a gentleman by the standards of the day, appearing simply as ‘Newland’ at the bottom of Sir John Oglander’s list of new year’s gifts received in 1622, the only donor denied a polite ‘Mr’, a ‘Goodman’ or even a Christian name.

Whatever talents he possessed for provisioning the Virginia Company’s ships, Newland was not especially well lettered, judging from the only correspondence of his to survive among the company’s records. The letter reveals his poor grasp of composition and punctuation and his erratic spelling, but if you read it aloud, his strong Hampshire voice rings through.30 Its first paragraph concerns shirts, packed away in a chest in the ship’s hold and therefore out of reach of the poor passengers, many of whom had endured a full month without changing their shirts. Newland’s tone is defensive, as if he is responding to a complaint about his charges:

Sr. Youers of the 18 of this instant I Recavd and you say that Capten Barwik had order to opene the Chest vher the shirtes is but thoues Chist ar stod in the ship and ar not to be Com by Some of youer pepell hath gon a month in a shirt so that of nesitie they most have Chaing I do for you as for my sell nothing but what Nesistie is done the fordrence paseger hath ben 2 times at the Coues to goe abord but the wind is Come to the wastward a gaine so now that be hear at Nuport and Capten Barwike will not leat his pepell Remane a bord befor the wind is faier.

Newland will have needed all his mercantile skills to provision the company’s ships with sufficient food, fuel and general stores for the long sea crossing, and to sustain the new settlers during their first year in the colony. The Marmaduke maids were dispatched at such speed that they travelled empty-handed, without the usual provisions aside from clothes provided by the company and bedding: two trusses ‘for use at sea’ containing six bed cases and bolsters, six rugs, two psalters and twelve catechism books, the last two items to be delivered to the master’s mate, Mr Andrews, for the maids’ use.31 A further half-barrel contained six pairs of sheets, six bed cases and six bolsters, intended perhaps for six of the maids when they arrived in Virginia.32

The thirteen maids were not the only settlers travelling to Virginia that summer. Also on board the Marmaduke were ‘twelve lustie youths’ and stores bound for Martin’s Hundred,33 where gardener’s daughter Ann Jackson was joining her brother; forty more settlers for the plantation would follow in the Warwick. The Virginia Company’s ‘husband’ or chief accountant dutifully recorded the goods loaded onto the Marmaduke destined for this plantation: four barrels of peas; two herring barrels of oatmeal; eight more barrels of meal; a ten-gallon cask of spirits (‘aquavite’); a four-gallon cask of oil; six shovels and spades; a cask of tools containing eight axes, four hatchets, six broad and six narrow hoes; a dozen each of shirts, pairs of sheets, frieze suits and Irish stockings; two dozen falling bands (flat collars falling on the shoulders); and two dozen pairs of shoes.34 Also travelling – three to a bed – were twelve boys, kitted out with canvas suits, shoes, stockings, garters, headbands, knives, points or fasteners for their clothes, plus two shirts apiece. Such a full load of passengers and cargo left little room for the passengers’ personal belongings. Mary Ghibbs’s ‘small packe of cloaths’ was confused with one belonging to a Mr Atkinson and left behind, to be sent on later in the Tiger.35

Keeping discrete accounts for separate ventures was another challenge that Newland did not always get right. Expenses incurred by the maids should have been charged to the magazine of named investors who had adventured the money for their passage and expected to share in the profits from their sale to prospective husbands, but Newland mistakenly charged them to the general company.36 The £9 3s. he claimed to have laid out for the Marmaduke maids during their stay on the Isle of Wight suggests that they remained on the island for at least four weeks, since Newland himself would later receive 3s. 6d. per week for each Scottish soldier billeted on him in late 1627.37

They must have been relieved to be finally on their way – the thirteen maids no less than Robert Newland, his responsibility for their welfare finally acquitted. One imagines that hopes and fears conflicted as they set off from the shoreline towards their ostensible goal: finding a husband in a distant land, a goal that united and divided them at the same time. Now sisters-in-arms but soon they would be rivals, if not in love then at least in the marriage stakes.

Their situation set them apart from most women sailing to Virginia, who usually travelled as wives or as indentured servants. Ann Jackson’s brother had in all likelihood married his wife in England before setting out for Virginia,38 like five young men who married in the parish church of Sts Thomas at Newport, Isle of Wight, on 11 February 1621. ‘Last fyve cupple were for Virginia,’ reads a note in the parish register after their names: Henry Bushell and Alice Crocker, Christopher Cradock and Alice Cook, Edward Marshall and Marye Mitchel, Walter Beare and Anne Green, Robert Gullafer and Joan Pie.39 They sailed to Jamestown on the Abigail so successfully provisioned by Robert Newland, who may even have persuaded them to go and will certainly have talked of their example to the Marmaduke maids, who followed just a few months later. However, such was mortality in Virginia that four years on, not one of the couples survived intact, although two of the men were living as servants, and one or other of the women may have been widowed and married again.40 The rest were almost certainly dead.

The Marmaduke maids’ haunting last view of England can be imagined from this map of the Isle of Wight engraved by Jodocus Hondius and published by John Speed in 1611.

The thirteen young women now taking ship have no husbands as yet. Instead, they have agreed to sail across a treacherous ocean to marry men as yet unseen in a place of conflicting histories, part Eden, part savage wilderness.

Stay with them as they reach the Marmaduke out in the Solent and clamber as tidily as they can aboard the merchantman, stopping to take one long last look at the island, a gentle, very English landscape of trees, pastures and meadows, the wooded promontories on either side of the River Medina enclosing the natural harbour at Cowes like mittened hands.41 Leaving home is hard at the best of times, and these women will have known they had little hope of ever returning. Would you have been brave enough – or foolish enough – to follow in their wake?

CHAPTER TWO

The Warwick Women

A few weeks after the Marmaduke sailed from East Cowes, a much larger group of around one hundred settlers – men and women – left Gravesend for Virginia in the good ship Warwick under Captain Arthur Guy and Master Nicholas Norburne.1 Their instructions were to set sail from England ‘with the first oppertunity of wynd and weather’ after loading goods, provisions and passengers, taking the direct route to Jamestown ‘accordinge to their best skill and knowledge’. Piracy or attack by an enemy ‘man of warre’ was a distinct possibility, in which case their orders were to ‘hinder their proceedinges or doe them violence’ as far as they were able.

Among the passengers were another thirty-six ‘Maydes and Younge Woemen’ assembled by the Virginia Company as part of its money-making plan to supply brides for planters who could afford to pay for them.2 Like the Marmaduke maids before them, they came with guarantees of provenance and personal recommendations from city and parish worthies, and each travelled with a bride price on her head.

Lying some twenty-two miles due east of London, or twenty-six miles if you travelled by the snaking River Thames, Gravesend and its sister parish of Milton had been a hythe or landing place for river traffic since the Domesday survey at least.3 The heart of the City was only a flood tide away, allowing ships a quick passage upriver, while the Kent and Essex shores on either bank provided safe anchorage should they need it. The town’s nightingales were much praised and its air was reputedly healthy, unlike Tilbury Fort directly across the Thames, whose inhabitants suffered constant agues from the ‘effluvia’ of the surrounding marshes.

For many foreigners arriving on these shores, Gravesend afforded their first sight of England and they were not always overly impressed. Visiting at the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, Swiss medical student Thomas Platter noted that the town lacked walls, was not especially large and had ‘very little to be seen’, despite its many inns, where he stayed just one night before taking a small boat to London with the incoming tide.4 More than a decade later, the Roman Catholic priest Orazio Busino came to England in the train of Piero Contarini, Venetian ambassador to the court of King James. They too stopped at Gravesend after a tempestuous sea crossing from France, dropping anchor as soon as they reached the Thames estuary since both wind and tide were against them. They went to the Post Inn, which was apparently accustomed to receiving ambassadors and foreign grandees, but found its charges exorbitant, ‘namely 2 golden crowns per meal for each person’, and so like Thomas Platter before them, they quickly hurried away.5

But Gravesend was in business to service ships and travellers on their way to and from the capital, not to keep them entertained, and its watermen clung to their ancient privilege of transporting His Majesty’s subjects by the ‘long ferry’ that plied between Gravesend and London. They faced increasingly fierce competition from the owners of the smaller tilt boats, so-called because passengers sat on bales of straw under a ‘tilt’ or canvas that shielded them from the worst of the weather. The journey by public barge cost twopence per passenger, rowed by four men in fair tides and five in foul weather, plus a steersman at least. Fatal drownings were a fact of travel but thankfully rare. Tilt boats could carry up to thirty passengers for a maximum fare of fifteen shillings per boat, or sixpence per passenger, three times the cost of travelling by barge.6

The journey for the Warwick maids began at Billingsgate Quay, where they caught the long ferry to Gravesend.

The long ferry and much of the river traffic from London to Gravesend set out from Billingsgate Quay just to the east of London’s only bridge, which presented a hazard to smaller boats shooting between the piers, especially at low tide.7 Here at Billingsgate the Warwick women will have started their long journey to Jamestown, having first gathered at the house of Deputy Treasurer John Ferrar in St Sithes Lane close to the City’s pulsing heart. During the years when Sir Edwin Sandys effectively controlled the Virginia Company, its administration was centred here in the merchant household of the Ferrars.

Treasurer Sandys was the prime mover behind the plan to send brides to Virginia, determined to increase the colony’s population by tying down its rootless male settlers with the bonds of family and children. He even provided the link to one of the women who gathered at Billingsgate, twenty-five-year-old Cicely Bray from Gloucestershire, her parents described as ‘gentelfolke of good esteeme’ and herself as being ‘of kine [kin] to Sir Edwin Sandys’. Nicholas Ferrar inscribed her name first in his catalogue of thirty-six young women who sailed to Jamestown on the Warwick, giving her the prominence and flourish due to her rank, before handing the pen to his secretary Tristram Conyam to enumerate the other thirty-five.

Viewed as a group, the Warwick women were less illustrious than their Marmaduke sisters: just four out of thirty-six could claim gentry status. Immediately after Cicely Bray came Elizabeth Markham, one of only two sixteen-year-olds to sail on the Warwick. Tristram Conyam had corrected her father’s first name from ‘James’ to ‘Jervis’, surely the writer Gervase Markham, whose books on husbandry and housewifery had already reached the colony, bound together and sent on the Supply in September 1620.8 A younger son of a well connected but largely penurious branch of the Nottinghamshire Markhams, Gervase Markham was closely identified with Shakespeare’s patron the Earl of Southampton, having dedicated a rather florid sonnet to him and fought alongside him in military campaigns led by the Earl of Essex. They may even have studied together at Cambridge, since Markham would later claim to have ‘lived many yeares where I daily saw this Earle’.9

Both Markham and Southampton were lucky to escape the devastating consequences that followed the Earl of Essex’s fall from grace. On 23 February 1601, two days before Essex was executed for treason, Gervase Markham married Mary Gelsthorp at the church of the Holy Cross in her home parish of Epperstone, Nottinghamshire, and retreated to the country, where he lived quietly as a tenant farmer with his rapidly expanding family before returning to London a decade or so later, perhaps to the parish of St Giles Cripplegate, where he would eventually be buried. We are told that young Elizabeth was ‘by her father and mother presented’, so both her parents were still alive by the time she left for Virginia. The year after her departure Gervase Markham proposed a bizarre wager to walk from London to Berwick on the Scottish borders without crossing any bridges or travelling by any sort of boat, claiming that he had ‘groune pore’ because of his ‘many children and greate Charge of househoulde’.10 Was this a penance, perhaps, for having encouraged or allowed his young daughter to travel to Virginia?

A third gentry maid was the orphaned Lucy Remnant from Guildford in Surrey, who claimed Sir William Russell as her maternal uncle. Lucy’s father, Antony Remnant, had married Russell’s sister Mary as his second wife on 13 January 1595 at the church of St Mary the Virgin, Worplesdon, and the couple settled at Pirbright on the outskirts of Guildford. Their union was blessed with a son just nine months later, followed by Lucy (baptized 1 May 1598) and at least two more daughters, all baptized at the ancient church of St Michael and All Angels, Pirbright, where their father was buried when Lucy was just twelve years old.11

All we know of the fourth gentry maid to travel on the Warwick, nineteen-year-old Elizabeth Nevill, is that she was born in Westminster, the daughter of a ‘Gentleman of worth’, and that her mother’s name was Frauncis Travis, facts attested ‘by divers of the Company on their owne knowledge’, together with her ‘good Carriage’. Information about the parentage of her companions is equally sketchy. Their fathers or kinsmen included clothworkers, a cutler, a draper, a baker, a victualler, a tailor, a hat maker and a plasterer from Oxford, but the father’s occupation for twenty-three women was not recorded. Eleven of the Warwick maids were born in London, Middlesex or Westminster; seventeen came from elsewhere, while nothing is known about the birthplace of the other eight.

Parish records nonetheless survive for some of the non-gentry women who gathered at Billingsgate at the start of their long voyage to Jamestown. One whose footsteps we shall track is Bridgett Crofte, born in the Wiltshire parish of Britford (old name Burford) and a little older than the age she gave to the Virginia Company, turning twenty as she crossed the Atlantic.12 The church where she was baptized still stands, fragments dating back to Saxon times, surrounded by ancient water meadows with fine views towards Salisbury cathedral. ‘The City of Salisbury is made pleasant with waters running through the streetes,’ wrote the Jacobean gentleman traveller Fynes Moryson, ‘and is beautified with a stately Cathedrall Church, and the Colledge [of] the Deane and Prebends, having rich Inhabitants in so pleasant a seate’.13

From further north came Jennet Rimmer, aged twenty, ‘borne at NorthMills [North Meols] in Lanckisher’, a parish near presentday Southport, which was virtually waterlogged until its meres and marshlands were drained in the nineteenth century.14 In the decade or so between November 1595 and February 1605 at least eleven male Rimmers in North Meols produced a host of children, despite a five-year gap in the records.15

Among the London-born maids, birth records survive for Sara Crose,16 daughter of baker Peter Crose; a Peter Crosse was still living in the parish of St Margaret Lothbury in 1638.17 And the records throw up two possible infant girls for nineteen-year-old Elizabeth Dag, born in Limehouse on the Thames between Ratcliff and Poplar: either Elizabeth Dage, daughter of Robert, baptized at the church of St Dunstan and All Saints in Stepney on 15 May 1603, or her namesake baptized at the same church on 26 September 1604, the daughter of John Dagg, ‘mariner of Lymehouse’.18 While the maiden name of Ann is unknown, her husband was surely the John Richards buried at St James Clerkenwell in the county of Middlesex on 20 June 1619, the very church whose parishioners gave Ann a glowing testimonial to send her on her way to Virginia.19 The birthplace of the other two widows, Marie Daucks and Elizabeth Grinley, is unknown.

Information about the Warwick women’s skills is also patchier than for those who sailed on the Marmaduke, although Tristram Conyam noted that Parnell Tenton ‘cann worke all kinds of ordinary workes’, that Ellen Borne was ‘skilfull in many workes’ and that Martha Baker was ‘skillfull in weavinge and makinge of silke poynts’. Interest in the women’s suitability as brides had shifted from practical skills to moral worth. Stock phrases recurred like a refrain; to be called ‘honest’ was the highest accolade. Ellen Davy was praised for her ‘honest and Good Carriadge’ and Alse Dollinges as a ‘Mayde of honest Conversation’. Ann Parker, in service with a scrivener, was labelled an ‘honest and faythfull servant’. Two maids – Ann Westcote and Mary Morrice – were described as ‘honeste and sober’, and three more praised for the honesty of their immediate family, echoing the advice of the pamphleteer Joseph Swetnam that ‘in choyse of a wife, a man should note the honesty of the parents, for it is a likelyhood that those children which are vertuously brought up will follow the steps of their parents’.20 Both parents of Londoner Frauncis Broadbottom were described as ‘very honest people’. Alse Dauson was brought up by her mother, ‘whom Mrs Ferrar reportes to be a verrie honest woman’, and Mary Thomas by her grandfather Roger Tudor, clothworker, ‘known for a verrie honest Man by divers of the Company’.

And here lies a clue to how the Virginia Company recruited many of its women: by word of mouth and personal acquaintance. Company personnel from the top downwards had clearly trawled among their relatives and friends for suitable brides, such as Treasurer Sandys’ Gloucestershire kinswoman Cicely Bray and Alse Dauson, the daughter of old Mistress Ferrar’s acquaintance. Their words of commendation reflect the chatter of the times, as those connected to the company spread the word about the kind of upright young women it was seeking, doubtless emphasizing the venture’s opportunities for advancement. The Earl of Southampton’s wide circle of patronage may have netted Gervase Markham’s sixteen-year-old daughter Elizabeth as well as Lettice King, who travelled out in the Marmaduke.

Other company personnel who personally recommended potential brides include company secretary Edward Collingwood (Ann Westcote) and merchant William Webb,21 whose post as the Virginia Company’s ‘husband’ was created to increase investor confidence in the organization’s affairs (Mary Morrice). ‘Robert the porter’ who introduced the orphaned Bridgett Crofte from Wiltshire was surely Robert Peasly, confirmed in his post only in May 1622 but already well known to senior officials. His appointment to the company’s warehouse followed the sacking of the previous incumbent, James Hooper, who was caught with tobacco thrust up his hose. Robert’s appointment went as high as the company’s court, which discussed a motion to employ ‘one Robert Peasly who was well knowne to divers of the Companie to be sufficient for the place and one that proffered good security for his truth upon wch good report and promise of Security the Companie have entertayned the said Robert Peasly for their Porter’.22

The two men charged with running the now defunct Virginia lotteries, Lott Peere and Gabriel Barbor, both had links to twenty-year-old Mary Ghibbs from Cambridgeshire, who had sailed on the Marmaduke