8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

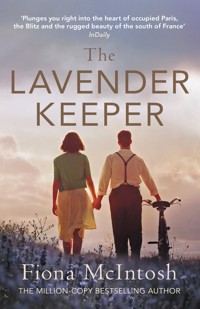

Provence, 1942 Luc Bonet, brought up by a wealthy Jewish family in the foothills of the French Alps, finds his life shattered by the brutality of Nazi soldiers. Leaving his abandoned lavender fields behind, Luc joins the French Resistance in a quest for revenge. Paris, 1943 Lisette Forestier is on a mission: to work her way into the heart of a senior German officer, and to infiltrate the very masterminds of the Gestapo. But can she balance the line between love and lies? The one thing Luc and Lisette hadn't counted on was meeting each other. Who, if anyone, can be trusted - and will their own emotions become the greatest betrayers of all? Readers love The Lavender Keeper: 'A perfect read for me. The setting of Southern France is romantic and beautifully described and the book's two plots intertwine seamlessly ... a different and unexpected love story of a small but important part of the war effort in England and France' 'The story weaves its way through many twists and turns that made it difficult for me to put the book down' 'Beautifully written and so meticulously researched, this gripping story of wartime France holds the reader's attention to the very end. I'm so glad that there is a sequel!' 'So often I felt as though I was smelling the lavender, walking the route of the characters in Provence and the streets of Paris'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 665

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

1

2

3

The Lavender Keeper

FIONA MCINTOSH

5

Dedicated to the Crotet family: Marcel, Françoise, Laurent, Severine and especially to Louis – a maquisard at sixteen years old – with whom we shared a meal and friendship one summer’s afternoon in Provence.

6

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

PART TWO

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

PART THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

PART FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

About the Author

By Fiona McIntosh

Copyright

PART ONE

8

CHAPTER ONE

12th July 1942

Luc loved this light on the lavender in summer, just before sunset. The field’s hedgerow deepened to glowing emerald and finally to dark sentinels, while the pebbly rows between the mounds of purple blooms became smudges of shadow. The lavender spikes, so straight and tall, never failed to mesmerise him. His gaze was drawn to the bright head of a wild scarlet poppy. No wonder artists flocked to the region in summer, he thought … or used to, before the world went mad and exploded with bombs and gunfire.

The young woman next to him did up the top button of her frayed summery blouse. Stray wisps of her long red hair fell across her face to hide grey-green eyes and her irritation. ‘You’re very quiet,’ Catherine said.

Luc blinked out of his reverie, guilty that he’d briefly forgotten she was there. ‘I’m just admiring the scenery,’ he said softly.

She cut him a rueful glance as she straightened her clothes. ‘I wish you did mean me and not your lavender fields.’

10He grinned and it seemed to infuriate her. It was obvious Catherine was keen for marriage and children – all the village girls were. Catherine was pretty and much too accommodating, Luc thought, with a stab of contrition. There had been other women in his life, not all so generous, but Catherine obliged because she wanted more. She deserved it – or certainly deserved better. She knew he saw others but she seemed to have a marvellous ability to contain her jealousy, unlike any other woman he’d known.

He brushed some of the tiny purple flowers from her hair and leant sideways to kiss her neck. ‘Mmm,’ he said. ‘You smell of my lavender.’

‘I’m surprised I haven’t been stung by the bees as well. Perhaps we should consider how nice a bed might be?’

He sensed she was leading up to the question he dreaded. It was time to go. He stood in a fluid motion and offered her a hand. ‘I told you, the bees aren’t interested in you. Ask Laurent. The bees are greedy for the pollen only.’ He waved an arm in a wide arc. ‘It’s their annual feast and they have a queen to service, young to raise, honey to make.’

She didn’t look, busy buckling the belt that cinched her small waist. ‘Anyway, Luc, it’s not your lavender. It’s your father’s,’ she said. She sounded miffed.

Luc sighed inwardly, wondering whether it was time to tell her the truth. It would be public knowledge soon enough anyway. ‘Actually, Catherine, my father has given me all the fields.’

‘What?’ Her head snapped up, as the expression on her heart-shaped face creased into a frown.

Luc shrugged. He wasn’t even sure his sisters knew yet – not that they’d mind – but his annoyance had flared at Catherine’s 11hostile tone. ‘On his last trip south he gave them all to me.’ He knew he shouldn’t enjoy watching her angry eyes dull now with confusion.

‘All of them?’ she repeated in disbelief.

He opted for a helpless grin. ‘His decision, not mine.’

‘But that makes you a main landowner for the whole Luberon region. Probably even the largest grower.’ It sounded like an accusation.

‘I suppose it does,’ he replied casually. ‘He wants me to take full responsibility for cultivating the lavender. It has to be protected, especially now.’ He began to amble away, encouraging her to start the walk home. ‘My father spends more time in Paris with his other businesses than he does down here … and besides, I was raised in Saignon. He wasn’t. This place is in my blood. And the lavender has always been my passion. It’s not for him.’

She regarded him hungrily. Now she had even more reason to secure him. But the more she demanded it, the more he resisted. It wasn’t that he didn’t like Catherine; she was often funny, always sensuous and graceful. But there were aspects of her character he didn’t admire, and he disliked her cynicism and lack of empathy. As a teenager he could remember her laughing at one of the village boys who had a stutter, and he knew it was her who’d started a rumour about poor Hélène from the next hamlet. He’d watched, too, her dislocation from the plight of the French under the German regime. For the time being her life was unaffected, and it bothered Luc that her view was blinkered. She never spoke about dreams, only about practicalities – marriage, security, money. Catherine was entirely self-centred.

‘I can’t think about anything but making these fields as 12productive as I can. These aren’t times to be planning too far ahead,’ he continued, trying to be diplomatic. ‘Don’t scowl.’ He turned to touch her cheek affectionately.

She batted his hand away coldly. ‘Luc, Saignon may be in your soul but it doesn’t run in your blood.’

When things didn’t go Catherine’s way she usually struck back. Hers was a cruel barb but an old one. Luc had been an orphan and most of the villagers knew he was an interloper. But he might as well have been born to the Bonet family – he had been only a few weeks old when they took him in, gave him their name and made the tall, pink stone house in the village square his home.

His lighter features set him apart from the rest of his family, and his taller, broader frame singled him out in the Apt region. All he knew was that his ageing language teacher had found him abandoned and had brought him to Saignon, where Golda Bonet, who had recently lost a newborn child of her own, welcomed his tiny body to her bosom, and into her family.

No one knew where he had come from and he certainly didn’t care. He loved his father, Jacob, his mother, Golda, and his grandmother, Ida, as well as his trio of dark-haired sisters. Sarah, Rachel and Gitel were petite and attractive like their mother, although Rachel was the prettiest. Luc, with his strong jawline, slightly hooded brow, symmetrical square face and searing blue gaze stood like a golden giant among them.

‘Why are you so angry, Catherine?’ he asked, trying to deflect this attack.

‘Luc, you promised we would be engaged by—’

‘I made no such promise.’

He watched her summon every ounce of willpower to control herself; he couldn’t help but admire her.

13‘But you did say we might be married some day.’

‘I responded to your offer of marriage by saying that “one day we might”. That is not an affirmation. You were spoiling for an argument then, as you are now.’

Her large eyes were sparking with anger, and yet again he watched her wrestle that emotion back under control.

‘Let’s not fight, my love,’ she said affectionately, reaching to do up a couple of buttons on his shirt, skimming the skin beneath.

But he did not love Catherine … nor want a wife in this chaotic world they found themselves in. If not Catherine, then Sophie or Aurelie in nearby villages, or even gentle Marguerite in Apt would grant him a roll in the hay – or the lavender.

‘What are you smiling about?’ Catherine asked.

He couldn’t tell her he was amused by her manipulative nature. ‘Your flushed cheeks. You’re always at your prettiest after—’

She put a hand to his lips. ‘Please, make an honest woman of me.’ She smoothed her skirt. ‘We don’t even need an engagement; let’s just be married and we can make love in a bed as Monsieur and Madame—’

‘Catherine, stop. I have no intention of marrying anyone right now. Let’s stop seeing one another if it’s causing you so much grief.’

Her expression lost its mistiness; her eyes narrowed and her mouth formed a line of silent anger.

‘We are at war,’ he reminded her, a plaintive tone in his voice. ‘France is occupied by Germans!’

She looked around her, feigning astonishment. ‘Where?’

Luc felt a stab of disappointment at her shallow view. Up this high, they were still relatively untroubled by the German 14soldiers, but his father’s letters from Paris were becoming increasingly frantic. The people in the north – in the occupied territories – were suffering enormous economic and social pressure, and those in the capital were bearing the brunt of it.

‘So many of those who fled here at the invasion have already gone back north,’ Catherine said, sneering. ‘All the Parisians have returned. You know it! They’re not scared.’ She gave a careless shrug. ‘It doesn’t really affect us. Why should we worry?’

‘They’ve gone back,’ he began, quietly despairing, ‘because it feels so hopeless. Their homes, their friends, their livelihoods are in the Occupied Zone. They ran south fearing for their lives; they’ve since decided to learn how to live among the Boches.’ He spat on the ground at the mention of the Germans. ‘The northerners have no choice. It doesn’t mean they like it, or that we have to support the Germans.’

‘You’d better not let Gendarme Landry catch you talking like that.’

‘I’m not scared of Pierre Landry.’

She looked up at him, shocked. ‘Be careful, Luc. He’s dangerous.’

‘You’re the one who should be careful pandering to his demands. I know your family gives him a chicken once a month to stay on his good side.’

Catherine glanced around nervously. ‘You’re going to get yourself into trouble if you keep talking like that. I don’t want to be shot for denouncing the Marshal.’

‘Marshal Pétain was a hero in the Great War, but he was not up to the job to lead our nation. Vichy is surely a joke, and now we have the ultimate Nazi puppet leading us. Laval more than dances to Hitler’s tune; in fact, he’s destroying our great democracy and adopting the totalitarian—’

15She covered her ears and looked genuinely anxious. Luc stopped. Catherine was raised as a simple country girl who figured obedience to the Vichy government’s militia was the best way for France. And in some respects, perhaps she could be right – but only if you were the sort of person who was content being subservient to a gang of avaricious and racist bullies who were dismantling France’s sovereign rights. A collaborator! The very word made his gut twist. He didn’t know he had such strong political leanings until he’d begun to hear the stories from his father of what it was like to experience Paris – Paris! – being overrun by German soldiers. The realisation that his beloved capital had opened her doors and shrunk back like a cowed dog before Hitler’s marauding army had brought disillusionment into his life, as it had for so many young French. It had seemed unthinkable that France would capitulate after all the heroics of the Great War.

His acrimony had hardened to a kernel of hate for the Germans, and on each occasion that German soldiers had ventured close to his home, Luc had taken action.

It was he who thought to blockade the spring, said to date back to Roman times, which fed the famous fountain in the village. By the time the German soldiers, parched and exhausted, had made their way up the steep hill into Saignon, the fountain was no longer running. All the villagers watched the thirsty soldiers drinking from the still water at the fountain’s base, smiling as the Germans drank what was reserved for the horses and donkeys of the village. On another occasion he and Laurent had stopped the progress of German motorbikes by felling a tree onto the road. A small win, but Luc was thrilled to see the soldiers, scratching their heads and turning tail.

16‘One day I’ll kill a German for you, Catherine,’ Luc promised, unable to fully dampen the fire that had begun to smoulder within.

‘I hate it when you talk like this. It frightens me.’

He ran a hand through his hair, realising he was behaving like a bully; she had no political knowledge. After all, if the Luberon kept its collective head down and continued to supply the German war effort with food and produce, this rural part of Provence might escape the war unscathed.

‘Listen, I’m sorry that I’ve upset you,’ he began, more gently. ‘How about we—’ He didn’t get any further, interrupted by a familiar voice calling to him.

Laurent appeared, breathless and flushed. He bent over, panting. ‘I knew where I’d find you,’ he gasped. Laurent glanced shyly at Catherine; he was continually impressed at Luc’s way with the local girls.

‘What is it?’ Luc asked.

‘Your parents.’

‘What about them?’ Immediately Luc’s belly flipped. He had a recurring nightmare that his family were all killed – his parents, grandmother, and his three sisters – in some sort of German reprisal for his bad thoughts.

‘They’re home!’ Laurent said excitedly. ‘I was sent to find you.’

‘Home?’ Luc couldn’t believe it. ‘You mean, Saignon?’

Laurent looked at him as though he were daft. ‘Where else do I mean? In the village right now, kissing and hugging everyone. Only you are missing.’

Now Luc’s belly flipped for different reasons. He gave Catherine a slightly more lingering kiss than could be considered perfunctory. ‘I’ll see you soon, eh?’

‘When?’ she asked.

17‘Saturday.’

‘Today’s Saturday!’ she snapped.

‘Monday, then. I promise.’ He reached for her but she slapped his hand away.

She glared at Laurent, who quickly walked a little way off. ‘Luc, tell me this. Do you love me?’

‘Love? In these uncertain times?’

She gave a sound of despair. ‘I’ve been patient, but if you love me, you will marry me, whether it’s now or later. I have to believe in a future. Do you love me?’ It came out almost as a snarl.

His long pause was telling. ‘No, Catherine, I don’t.’

Luc turned and walked away, leaving Catherine stunned, her face hardening into a resolve burning with simmering wrath. ‘Your family’s money might give you your proud, arrogant air, Luc – but you’re just as vulnerable as the rest of us,’ she warned.

Laurent’s face creased with concern at her words. He cast a despairing look at Luc’s back before turning once again to Catherine. ‘Will you let me see you home?’

‘I’m not helpless, Monsieur Martin,’ she said, in a scathing tone.

Laurent’s cheeks coloured.

She shrugged. ‘As you wish.’

Laurent kept his silence as they made their way back up the hill. He didn’t even look around when his shirt got caught on an overhanging branch. He heard it rip, but didn’t care about anything right now, other than walking with the woman he had loved since he was a child.

The scene with Catherine was already forgotten; the dash home had cleared Luc’s head and by the time he’d made it to the top of the hill, he was feeling relieved that he’d finally spoken plainly to her.

18It was young Gitel who saw him first. ‘Luc!’ she yelled, gleefully running towards him and launching herself into his arms.

He gave a loud grunt. ‘What are they feeding you in Paris? Look how tall you’ve become!’ he said, instantly worrying at how petite she seemed. He swung her around, enjoying her squeals of delight. Gitel was nine and Luc loved her exuberance, but she was small for her age and her eyes were sunken. Luc did his best to indulge her, and his elder sisters were always warning him that the way he spoilt Gitel would ruin her perspective on life. He’d scoffed, wondering how any youngster could grow up in Paris since 1939 and not have a skewed view of life. Luc didn’t believe any of them could cosset Gitel enough and wished he could persuade his parents to leave her in Saignon. But she was bright and eager to learn at her excellent lycée in Paris. She possessed an ear for music, a sweet voice and a love for the dramatic arts. Her dream was to write a great novel, but while Luc urged her to write down her stories, their father pushed her to keep up her science, her mother insisted on teaching her to sew, and her sisters despaired of her dreamy nature.

‘Have you been practising your English?’ Luc demanded. ‘The world will want to read you in English.’

‘Of course,’ she replied, in perfect English. ‘Have you been keeping up your German?’

It was his father who had insisted he learn German. He urged that the language would be useful in the lavender business in years to come. Luc had not questioned his father’s wisdom but had kept his German secret from the villagers.

‘Natürlich!’ he replied in a murmur. Luc kissed the top of his sister’s head. ‘Do you think old Wolf is any less relentless? 19I suspect your Miss Bonbon allows her junior students to get away with far more.’

Gitel was giggling. ‘Bourbon,’ she corrected.

He gave her plait a tug and winked.

Gitel’s expression changed. ‘Papa’s not happy. We had to make a mad dash from Paris. He’s barely let us pause to sleep and we weren’t allowed to stay in any hotels. We slept in the car, Luc! Mama is exhausted.’

Luc caught his father’s gaze and immediately saw the tension etched deeply in the set of his mouth, buried beneath a bushy, peppered beard. Jacob Bonet was instructing the housekeeper while amiably continuing a conversation with one of the neighbours. Luc knew him far too well, though, and beneath the jollity he saw the simmering worry in every brisk movement.

A new chill moved through him. Bad news was coming. He could sense it in the air in the same way that he could sense the moment to begin cutting the lavender, whose message also came to him on the wind through its perfume. His beloved saba insisted the lavender spoke to him and him alone. She invested the precious flowers with magical properties, and while her fanciful notions amused Luc, he hadn’t the heart to do anything but agree with her.

He watched her now, hobbling out to help with all the possessions that the family had brought south, from his mother’s favourite chair to boxes of books. Saba was muttering beneath her breath at all the disruption, but he knew she must be secretly thrilled to have everyone home. It had been just the two of them for a couple of years now.

His grandmother’s hands were large for her small, light frame – even tinier now that she was eighty-seven. And those 20hands had become gnarled and misshapen with arthritis but they were loving, ready to caress her grandson’s cheek or waggle an affectionate but warning finger when he teased her. And despite the pain in her joints, she still loved to dance. Sometimes Luc would gently scoop her up like a bird and twirl her around their parlour to music; they both knew she loved it.

‘The waltz was the only way a young couple could touch one another, and even through gloves I could feel the heat of your grandfather’s touch,’ she’d tell Luc, with a wicked glimmer in her eye.

Her hair, once black, was now steely silver, always tied back in a tight bun. He couldn’t remember ever seeing her hair down.

He watched the little woman he adored throw her hands apart in silent dismay as Gitel dropped a box.

‘Don’t worry, Saba. It’s only more books!’ Luc came up behind the tiny woman and hugged her. ‘More hungry mouths to cook for,’ he said gently, bending low to kiss. ‘Shall I trap some rabbits?’

She reached up to pat his cheek, her eyes filling with happiness. ‘We have some chickens to pluck. More than enough. But I might want some fresh lavender,’ she whispered and he grinned back. He loved it when Saba flavoured her dishes with his lavender.

‘You’ll have it,’ he promised and planted another kiss on the top of her head.

His elder sisters gave him tight, meaningful hugs. He was shocked at how thin they felt through their summery frocks, and it hurt to watch his mother begin to weep when she saw him. She was all but disappearing – so shrunken and frail.

21‘My boy, my boy,’ she said, as if in lament.

It was all terribly grim for a reunion. ‘Why are you crying?’ He smiled at his mother. ‘We’re all safe and together.’

She waved a hand as if too overcome to speak.

‘Go inside, my love,’ Jacob said in that tender voice he reserved for his wife. ‘We can manage this. Girls, help your mother inside. I need to speak with your brother.’

‘Let me—’ Luc began, but his father stilled him with a hand on his arm.

‘Come. Walk with me.’ Luc had never heard his normally jovial father as solemn.

‘Where are you going?’ Sarah complained softly. ‘We’ve only just arrived.’

Luc smiled at his eldest sister, trying his best to ignore the way her shoulders seemed to curve inwards, adding to her hollow look. ‘I’ll be back in a heartbeat,’ Luc whispered to her. ‘I want to know everything about Paris.’

‘Be careful what you wish for,’ Sarah warned, and the sorrow in her tone pinched Luc’s heart.

CHAPTER TWO

Luc fell in step with his father, who now appeared brittle enough to snap. ‘It’s so good to have you all back, but if we’d known, we could have made arrangements.’ He laid a hand across the older man’s shoulders and not even his father’s clothes could conceal the blades, hard and angular, that jutted beneath.

‘No time,’ Jacob admitted brusquely. ‘Where’s Wolf? I sent him a message ahead.’

‘We were planning a meal together tonight anyway. Saba is cooking his favourite.’

‘Good. I need to talk with him.’ His father sighed and looked up. ‘I used to run up this hill.’

Luc had registered his father’s far slower tread. ‘Are you well, Papa?’

His father looked down and Luc was astonished to see his lip quiver. ‘I don’t know what I am, son. But I am glad to see you.’ He linked arms with Luc. ‘Now, help me up this wretched hill. I would see my favourite valley from our lookout.’

23They said no more, walking slowly in comfortable silence as Luc guided his father through the tiny alleyways of the village, chased by the smells of cooking and echoes of people’s chatter through open shutters, ascending all the time to the great overhanging cliff. The sun had set by the time they reached the summit, but the evening was still bright enough in the Provence summer. Night wouldn’t claim the village for hours yet. Luc helped his father to sit, making him comfortable on a small outcrop of rock, trying to mask his confusion.

Jacob Bonet stayed wordless for a long time. He was not quite seventy and had been a businessman for most of his life, even though he’d begun as a lavender farmer. Jacob didn’t have the same affinity for the land that Luc had. Lavender had been the source of his family’s wealth but Jacob had used his inheritance and savings with skill and daring. By the time Jacob had been Luc’s age, he no longer had much to do with his family farms, and had managers supervising them. He could have sold them, but Jacob had been sentimental and kept them going. How glad Luc was that he had. Lavender had become highly profitable as the perfume industry had grown. But Jacob’s work was all about accounting and investment, not hard toil in a field. At seventy he shouldn’t be this frail, Luc thought with despair.

It was only now, looking at one of the people he most loved, that Luc was able to see how traumatised his father appeared. Jacob’s skin had a ghostly pallor and was stretched too thin over what had become an almost skeletal frame.

Luc felt guilty that his own body was so strong, muscular – even tanned. ‘Living in Paris has not been kind to our family,’ he remarked.

‘I have to educate your sisters, Luc. There’s nothing for your 24sisters here in Saignon. Can you imagine Sarah or Rachel not being able to use their bright minds? And Gitel? She needs what Paris offers.’ His father looked down. ‘We all do. It’s where my business is done.’ Then he lowered his head. ‘Was done.’ Jacob closed his eyes and inhaled. ‘What do you smell?’

It was a question he’d asked many times during Luc’s childhood but Luc hadn’t tired of it. He dwelt in the memory of far happier times overlooking this picturesque valley, with its patchwork of fields and orchards, olive groves and the tall stands of cypress deep blue in the dusk.

He cleared his throat to rid it of the sour taste that had gathered. ‘Lavender, of course,’ he answered. ‘And the thyme is strong this evening. As well as rosemary, mint and just a hint of sage. Oh, and Madame Blanc’s stew is already simmering in her pot.’

‘Mmm.’ His father nodded. ‘Heavy on the marjoram this evening.’

Luc smiled. ‘You didn’t bring me up here to discuss herbs.’

‘No. I just wanted to cling for a moment to the illusion that nothing has changed, that life is still simple and secure.’

‘Papa, tell me what has brought you here in such haste?’

The bell of Saint Mary’s tolled gravely in the distance. It was a twelfth-century Romanesque church that had been greeting pilgrims journeying to Italy and Spain since the Middle Ages, which accounted for its size and grandeur in their tiny village.

Jacob took a pipe from his pocket and tapped out the spent ash on a nearby rock. It was only now that Luc noticed a piece of yellow fabric, sewn onto his father’s jacket sleeve and shaped as a star. He was astonished to realise that it had the word Juif inked onto it.

‘What the hell is that?’ Luc asked.

25‘We’ve been wearing this now for a month or so, son.’ His father shrugged. ‘The decree came into effect in early June. Wherever we Jews are, we have to wear it.’

Luc stood, anger flaring. ‘They’ve already removed our people from every civil service position, from industry, from trade—’

His father finished for him. ‘Law, medicine, banking, hotels, property, even education. Benjamin Meyer has never recovered from losing his teaching position at the university. But it’s been steadily getting worse. All the confiscations of goods, all the humiliations add up. I’ve managed to protect our girls from the worst of it, but even I can’t keep them safe now.’

‘You have come home for good, then? We shall keep the family safe here.’

His father smiled sadly. ‘I’m not so sure about that, my son, not with the new Schutzhaft in place.’

Luc stared at him. It felt like an icy fist had suddenly clenched around his gut. ‘Schutzhaft?’ He knew what the word meant – detention and protection – but it didn’t make sense.

‘It’s the Gestapo’s generous way of keeping us Jews safe. Protective custody, it’s called, but it’s simply a front behind which they can hide as they drag us all off for imprisonment.’

‘Detention?’

‘It’s not just the Nazis. Our own French administrators are to blame too.’

‘The General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs was always—’

His father spat on the ground between where they sat, shocking Luc into silence.

‘They’re a corrupt and avaricious mob!’ Jacob snapped. ‘Vichy has embraced anti-Jewish ordinances with glee and is 26so anxious to prevent everything it confiscates from us from falling into German hands that most of our friends from the Occupied area are now destitute or being carted off to detention camps.’ His father gave a sad laugh. ‘And we’ve made it so easy for them. Like obedient sheep we’ve done everything asked of us, from going to the sub-prefectures and registering our names, the names of our parents, our children, our addresses. They have a complete record of every Jew in Paris. All of France, probably, for all I know.’

‘It’s just a list,’ Luc began.

But Jacob grabbed his shirtsleeve. ‘It’s not just a list, son. It’s information. And information is power! I have run my own business since I was nineteen, and information is the key. It’s why I’ve given you the lavender-growing business. I want you to learn early, understand what it is to be in charge, to learn the very thing I’m telling you now. Money makes you feel invincible, but it is a brittle shield, as you can see; my money is no true protection when you really need it. The real power is information; the authorities have all the might they need because we have meekly given them the means to find us, how many children we have, their names, even their photographs. They have confiscated our properties, our paintings, our silver, the chairs we sit on and tables we eat at. And no one fights them!’

Luc waited. His breath felt as ragged as his father’s voice sounded as Jacob continued. ‘It is information that kept us alive. I knew it was vital to get out of Paris, that something truly bad was coming, because I listened and paid the right people to inform me. I warned others; they didn’t all believe me and will pay a terrible price. And still they can hunt us. Hunt us like the vermin they believe we are.’ The old man’s voice broke and he put his face in his hands.

27Luc swallowed. It was all so much worse than he’d feared.

‘Can you believe it?’ his father asked. ‘Detention camps for honest, god-fearing citizens patriotic to France, who have fought for her and whose sons have died for her. They’re now being interred in shitholes like Drancy!’

Luc had never heard his father talk like this. But there was no more anger in Jacob’s voice. Luc realised his father was only now allowing his sorrows to surface.

‘It began in the eleventh arrondissement; they rounded up thousands of Jews and took them to Drancy … that was its official opening, you could say, last year. But there’s worse coming. Mark my words.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’ Luc asked, shocked.

His father shrugged painfully thin shoulders. ‘What could you do? I needed you here, carrying the burden of our farms. A lot of people count on us for their income.’

The words, though true, felt hollow to Luc. ‘The girls, they …?’

‘Sarah just wants to attend university and study the history of art. She wants to lecture.’ He gave a small, strangled sound. ‘They won’t let a Jew near a class any more! Rachel knows what’s happening but won’t discuss it in front of your mother and refuses to play her music. Gitel …’ He gave the saddest of smiles. ‘We need her to remain ignorant for as long as possible. It is only going to get worse.’

‘Stop saying that, Papa. We can keep the family safe here, I promise you.’

Jacob gave a tutting sound of despair. ‘Stop dreaming, Luc!’

Luc felt the sting of the rebuke. He didn’t know how to respond, but there was no doubting Jacob Bonet’s information. 28His family’s religious background made everyday life of Occupied Paris now impossibly hard to stay safe.

His father drew on the pipe and closed his eyes momentarily, enjoying its comfort.

‘So the apartment in Saint-Germain is …?’

‘Acquired,’ his father replied somberly, not opening his eyes. ‘The Germans love the Left Bank. We’ve been staying with friends for the last few months.’

‘What?’

‘I didn’t want to worry you until we knew more.’

His father was normally the most optimistic of men but he sounded so beaten that genuine dread crept into Luc’s heart.

‘What day is it today?’ Jacob asked.

‘Saturday.’

‘A fortnight gone already.’

Luc frowned. ‘What happened two weeks ago?’

‘Well, you’re aware that the Commission for Jewish Affairs has sanctioned all the German initiatives with barely a blink of conscience?’

Luc nodded, but didn’t say that he had failed to grasp that it was as determined as Hitler in discriminating against Jewish people. As critical as Luc was of the Germans, his loathing had increasingly been directed more at the French milice in the region. They were far more visible, far more demanding of the people of the provinces than any soldiers. The German soldiers he’d seen were mostly lads with pink faces and clean chins and a ready grin. They were as unlikely as he to look forward to killing.

His father continued. ‘Shops must carry signs stating that they are Jewish-owned; the Reich has been imposing hefty taxes on Jews. We’ve been forbidden from buying our 29groceries in certain places. Parks are now off limits. It’s no longer safe for Gitel’s friends to be seen playing with her. But until now we’ve been relatively safe so long as we obey rules and keep to ourselves.’

‘And now?’

‘Now property belonging to Jews is being confiscated as a matter of course. Families are being evicted. It’s unthinkable, although I shouldn’t be so surprised, given the rumours we’re hearing from Poland.’

Luc frowned. ‘Evicted and then what?’

‘They’re being rounded up, Luc.’

‘Rounded up?’

‘A lot of our men who fought in the Foreign Legion at the beginning of the war have already been deported to build the railway in the Sahara. I suppose we should have paid more attention to last year’s announcement that Jews were no longer able to emigrate.’

‘But, Father, to where? Why would you want to leave?’

Jacob Bonet turned to his son and smiled gently. ‘I let you all down. I should have got the girls away when I had the chance in 1939. But you were all still so young and your mother would have died of a broken heart if I’d sent her away. But I should have packed them off on a ship to America. Instead now all they have ahead of them are places like Drancy.’

‘Drancy isn’t interested in our family,’ Luc growled.

‘Do you really think the Gestapo has finished with the Jews? Drancy is surrounded by barbed wire. There are now five of its sub-camps around Paris. Last year they slaughtered forty inmates there in retaliation for an uprising. They despise us, want us gone. And by gone I don’t mean from Paris or even Provence. I mean obliterated.’ Luc’s heart skipped a beat 30as his father’s voice faltered. ‘They will hunt us down, north or south. There is nowhere for us to flee. I have tried, my boy, believe me. I, Jacob Bonet, cannot even bribe safe passage for my daughters out of Europe. The doors of France are closed and our so-called head of government has happily thrown away the key. Laval’s determination to follow the totalitarian Nazi regime will see every last Jew rounded up and thrown into camps. But there is talk that these camps like Drancy and Austerlitz are simply holding prisons.’

The hair at the back of Luc’s neck stood on end. He didn’t want to ask but still the question tumbled from his lips. ‘For what?’

‘For the master plan,’ his father murmured, clutching his pipe tightly. ‘I have heard that there is to be a concerted series of arrests as early as next week in Paris. No one is safe; no Jew will be spared. At first they only arrested gypsies, then foreigners – but that was a smokescreen. France has begun deporting its Jews east to work camps, but the rumours are that those not of use to the German war machine will simply be killed.’ He looked up and fixed Luc with a fierce gaze. ‘Except you.’

‘Me?’ Luc’s voice cracked in surprise. ‘Yes, as a farmer I’m considered part of essential services, but—’

Jacob gave a dismissive noise. ‘I didn’t mean …’ but his voice trailed off and he sighed heavily.

Luc’s frustration rose. ‘Papa, this is all hearsay. The rumour-mongers at work, surely? I mean, what would be the point to this obliteration you speak of?’

Jacob looked at Luc as though he were simple. ‘To rid Europe of its Jewish population, of course. I know that some have already been transported from Drancy to a place called Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland.’

31‘A new work camp?’

‘It may well be a work camp but it is also a place of death.’ Jacob held up a hand to prevent Luc jumping in. ‘Just a fortnight ago I saw an article smuggled into Paris that ran in The Telegraph about mass murders of Jews at Auschwitz. It’s a respected British newspaper and the news had been sent by the Polish Underground to its exiled government in London. The Nazis are now killing Jews systematically and in the tens of thousands. They’ll begin with the old, the infirm, the very young, the sick, the needy – making sure the fit and the young work until they can’t work any more, and then they’ll be exterminated too.’

Luc stood, bile rising in his throat. ‘Stop, Papa!’

‘Pay attention! This is not hearsay. This is fact. Genocide is underway.’

They faced each other; Jacob angered in his despair and Luc simmering with rage at the fate befalling his people.

‘Jacob?’ enquired a new voice.

‘Ah, Wolf,’ Jacob said, turning with a smile to greet his old friend as he crested the hill.

Despite having one leg shorter, Wolf was tall and heavily built with a knitted waistcoat straining across his round belly. He was the opposite in looks to Jacob Bonet, with thinning, wispy hair that had once been a reddish-gold escaping from beneath the straw hat he habitually wore. Like Jacob, Wolf wore a loosened tie and an ironed shirt, now slightly dampened and unbuttoned at the collar. He was breathing heavily at the effort of climbing the hill but he gave them both a broad grin. ‘Heavens, Jacob. Is that really you?’ he wheezed as he limped towards them.

‘It is,’ his father replied, standing with difficulty. ‘Here, let me bid you a proper welcome.’

32The two men embraced and stood back to look at each other, Wolf much taller, his eyes glistening with emotion.

‘The years are taking their toll, my friend,’ Wolf admitted, clearly shocked. ‘Beware the evening breeze coming down from the Massif. It will blow you over.’

‘You worry about yourself, old man!’ Jacob said gruffly, with obvious affection.

Wolf kissed Jacob’s cheeks. ‘It gladdens my heart to see you.’

‘I wondered if we’d make it here in one piece.’

‘All the women are well?’

Jacob nodded. ‘For now, Wolf, for now.’

Luc helped them both to sit side by side.

Wolf glanced over at him. ‘How are you, my boy? Alles ist gut?’

‘I don’t want to speak German!’ Luc retorted. ‘I don’t ever want to speak it again.’

‘Listen to me,’ Jacob growled. ‘Speaking German might save your life!’ He turned to Wolf. ‘Has he been practising?’

‘Practising? Luc can curse like a local.’

His father frowned. ‘How come?’

‘He slips down to Apt all the time.’

‘I didn’t see any soldiers there.’

‘They come and go,’ Wolf said. ‘They prefer L’Isle sur la Sorgue for obvious reasons.’

Luc hadn’t seen L’Isle sur la Sorgue since just before war broke out across Europe but he knew from his own family trips that the town was beautiful. It took its name from the pretty River Sorgue, whose tumbling, chilled waters fed a spring that traditionally attracted the wealthy on holiday. Now the town was full of loud, hard-drinking Germans on leave.

Heaven alone knew how Jacob had got the family down 33south without running into bother with soldiers or how he found enough petrol, but Luc didn’t dare ask. Even tucked this far away from Paris, he knew how hard it was to cross from the German Occupied Zone into Vichy France. Money still carried some weight, no doubt.

‘Have you spoken with German soldiers directly?’ asked Wolf.

Luc shrugged. ‘I listen a lot. When I speak I mix French in to make it clumsy. I sound like anyone else from around here.’

‘Good,’ his father replied. ‘You’ve never introduced yourself? None of them know your name?’

Luc felt bewildered by the intense questioning. ‘No. I have no desire to be friendly with the Germans. Why are you asking?’

‘I’m trying to save your life,’ Jacob replied.

Luc’s gaze fell. As true darkness closed in, the tiny village below began to illuminate itself. Beyond that the larger town of Apt sprawled like a star-dusted piece of velvet. He loved it here; the longest he’d ever left was to do his obligatory military service six years earlier. Unlike many of the other young men, the time away from home hadn’t given him a wanderlust; if anything, it had intensified his passion for the lavender fields of his home.

‘Don’t worry about me, Papa. Let’s just concern ourselves with Maman, Saba and the girls.’

His father’s next words were so chilling that Luc could barely take them in.

‘It is, I fear, too late for them … for us,’ Jacob replied in a soft voice. ‘But not for you, Luc.’

He regarded the two older men. His father had fought bravely for the French Legion during the Great War, and Wolf, with his crippled body, had fought on the other side, only to relinquish his German citizenship after the defeat and flee to France. They were 34both survivors. How could they adopt such a beaten attitude?

‘Too late?’ he finally repeated. ‘We can hide, we can—’

‘We can try, but it will always be different for you. The time is now,’ Jacob said, unnerving Luc. ‘I … I have something to confess.’

Luc blinked. Of all the things his father could have said, this was the most unlikely. ‘Confess?’

Jacob realised his pipe had gone out, muttered a low curse and began the slow process of relighting the tobacco. There was silence, save the puffing sound of Jacob sucking on the pipe expertly, drawing air through the bowl until the leaf caught and began to smoulder again. Soon the mellow, comforting aroma of his tobacco filled the air around them, combining with the cooking smells of the village, and Luc felt a momentary sense of peace.

Luc reached into his pocket and took out a stub of candle that he habitually carried; Jacob tossed him the matches and soon they were weakly illuminated, the tiny flame giving his elders an ethereal glow. He hadn’t imagined it – they both looked hesitant … no, fearful.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

They appeared to sigh as one.

‘What?’ Luc repeated. It was a demand now as he felt a strange fear penetrate his chest.

‘Luc,’ his father finally said, ‘my beloved and only son.’ He felt his throat tighten. The air felt thick with tension and an owl hooted mournfully from somewhere nearby. ‘We have lied to you.’

CHAPTER THREE

The two old men talked haltingly, and as one paused or hesitated, the other would take up the story. They punctuated their tale with affectionate reassurances, sharing long-secret memories of 1918, a year, Jacob said, in which two wonderful events had occurred – the Great War ended and Luc had come into their lives.

They talked until Luc vaguely registered the bell tower chiming the hour again, but his thoughts were swirling, his life suddenly a mess. Beneath the familiar sound of their voices, Luc tried to gather his wits but realised he was sitting in a vacuum of thought, hearing words but unable to truly absorb them.

‘Luc?’ Jacob asked.

The bell finished its sombre toll at eight. Saba would be tutting over her stove by now.

‘Luc?’ his father tried again. He sounded anxious.

A storm was gathering in his mind; he could feel it beginning 36to pound at his temple. He ground his jaw, dreading asking the question. Nevertheless he was compelled. ‘What is my real name?’

Jacob hesitated.

Wolf answered for him. ‘It is Lukas.’

Luc grimaced, closed his eyes. How could three letters of the alphabet turn his world on its head? And how could those same three letters change a simple name he liked into one that had instant connotations of evil?

He drew a deep breath to steady himself. ‘And my real family name?’

Wolf cleared his throat. ‘Ravensburg.’

Luc stood abruptly and walked away, no longer thinking, only reacting. If someone had just plunged a knife into him, it couldn’t have hurt more.

He was German.

Did it all make sense now? His fairer looks, his bigger build? So was this the reason his father had insisted on him learning the language until it was so ingrained he sometimes dreamt in German?

‘Who knows this?’

Jacob gave a small cough. ‘Your mother, grandmother, Wolf, obviously. Your sisters know nothing, other than that you are adopted. I cannot disguise that from anyone.’

Wolf rushed to continue. ‘Your birth parents were good people. Your father was a man called Dieter; he was younger than you when he was killed at the Front in 1918. Your mother, Klara, was younger still but she loved him. I knew her briefly – she was beautiful and fragile, and terribly weak during your birth. She lasted barely days, but long enough to fall in love with you.’

37‘The heavens are certainly having fun at my expense,’ Luc said darkly.

‘Don’t talk like that, son,’ Jacob said.

‘Son? I’m no son of yours,’ he said, shaking the large yellowed German birth certificate Wolf had produced. ‘I’ve been a pretender all of my life!’

Luc had his back to them both, staring out across the valley, beyond Apt, looking west to Avignon to where he knew the Germans gathered in numbers. He thought of their strong bodies, their sense of invincibility, golden hair and shining teeth, their smart uniforms and polished boots. He thought about how one of the Apt girls on a trip with her parents into Avignon had spoken of the men in black: paramilitary soldiers of the Schutzstaffel, strapping German SS in smart uniforms with distinctive insignia on their lapels, armbands, shoulders.

The shock was now giving way to anger and he had a momentary vision of himself killing faceless but laughing men in uniform; he couldn’t tell if they were soldiers or local milice – they were all the enemy; all responsible for this pain.

It seemed Wolf understood; he was as much a father to Luc as Jacob was, and had always been able to read Luc’s heart. As if listening in on Luc’s bleak thoughts now, the old man reached out to touch Luc on the arm.

‘There are ways to strike back.’ He gestured at the document in Luc’s fist. ‘You look German, you talk and swear like one, you are German,’ he emphasised, touching the birth certificate. ‘Use that to help yourself … to help France.’

Luc turned to look at him, confused. ‘What are you talking about?’

It was Jacob’s turn. ‘Listen to me, Luc. Look at me!’

Luc’s gaze slid unhappily to his father’s face.

38‘I can try to understand how this feels. If we could have spared you, we would have. What does it matter where you came from? You are French in your heart, you are Jewish in spirit and—’

Luc cut across his father’s words like a blade. ‘And I possess the killing soul of my kin!’

A slap echoed around, bouncing off the tiny natural amphitheatre that the rock face provided. The sting of it arrived seconds after, and it was only then that Luc realised that Wolf had struck him. There was passion in the blow.

‘Don’t you dare! Do you think your true father had a bad soul? I read his letters – he was just a young, lovestruck youth, doing his military service, obeying his orders and dying for his country. He didn’t want to kill. Few soldiers do. Dieter wanted to be with his wife, his son. And the woman who brought you into this world? God forgive you for tarnishing Klara’s memory. She was a young, frightened mother alone, and she begged me to make sure I taught you to think of her kindly. She wanted you to know that she loved you more than her own life. She was eighteen, Luc! She knew she was dying but I never once heard her grieve for herself. Her thoughts and prayers were only for you and for the soul of Dieter.’

Luc swallowed and looked down. He couldn’t bear to see the disappointment in Wolf’s eyes. He didn’t want to think of these young strangers as his parents, loving him, their dying thoughts of him.

Wolf’s anger wasn’t spent. ‘Do you think I have a killing soul, Luc? I am German. Or have you forgotten?’

Luc kept his eyes down, shamefaced.

‘Your conceit astonishes me. This filthy, ugly war is not about you!’ Wolf continued. ‘People are dying all over Europe. 39Your story is but one among millions. But you are that one among millions who may survive this war because of your parentage, because of the Bonets who have raised you and loved you and given you their name. Don’t you dare spit in their faces now! They didn’t tell you this for fun, but for your own protection.’

Wolf turned away, wiping his mouth of the spittle that had flown from it with a trembling, liver-spotted hand, and Luc saw him, perhaps for the first time, for the seventy-six-year-old man he was.

Luc glanced over at his father. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘For what?’ Jacob asked, sounding surprised.

‘For not being your real son.’

Jacob looked up, his eyes misting, and Luc’s heart felt close to breaking as he watched his father struggle laboriously to his feet, waving a helping hand away from Wolf. He limped to Luc, gazing up to look him in the eye.

‘You are my real son – real to me, to your mother, a grandson to your saba, a brother to your sisters.’ He held out his arms and Luc, without thinking, wrapped his father into a hug and wept.

Luc let Wolf and Jacob go ahead of him as he took a detour. He’d promised his grandmother some lavender, and he ran to the nearest of their fields to snatch some purple-headed stalks. The night was balmy and Luc was treated to wafts of perfume. The fields were telling him that it was just days now before he would need to prepare for harvest.

There would be far fewer workers to help this year, and Luc had heard that the Germans might be calling up able men from France to assist the German war machine. He grimaced 40at the thought, while his cheek was still warm with the sting of Wolf’s slap.

He went back over what the old men had finally revealed, after nearly a quarter of a century of secrecy. During the Great War, Wolf and his wife, Solange, had lived in Strasbourg, close to the German border in Alsace. Wolf had been too old to fight at the Front, and his limp prevented active service anyway. He was a linguistics professor at Strasbourg’s university, where he taught amongst other languages, Old Norse. As easily as changing clothes, Wolf had swapped from speaking German to French in his everyday dealings.

Despite his position, Wolf wanted to distance himself from Germany. He decided to leave Strasbourg once the war had ended. Just before departing, he and Solange had come across the heavily pregnant Klara Ravensburg, alone and in labour, trying to make it into France from her village in the Black Forest; she too was running away from Germany, a country that she blamed for killing her beloved Dieter. The day after the war ended Klara had received the full devastating news of Dieter’s accidental death. He had died in friendly fire just hours after the ceasefire. ‘Her mourning was just beginning while people were still drunk in the streets from celebrating,’ Wolf said in his gentle voice.

With Klara’s mother long dead and her father and brothers all killed at the Front, her heartbreak pushed her over the brink. In a stupor, without any belongings, she had walked out of her village and just kept going.

It was just chance and good luck that she’d collapsed in front of Wolf’s wife. ‘Solange took her into our home, bathed her, dried her, even hand-fed her – for she could do little for herself – combed her hair and sang her off to sleep,’ Wolf had explained to Luc.

41A baby boy was delivered amidst the chaotic and celebratory atmosphere of the Armistice. Luc was born on a chilly, drizzly, late November day in 1918 as Europe began to fully grasp that the Great War was over. Klara died soon after from complications.

Wolf and Solange left Strasbourg three days before Christmas, planning to head far south into the warmer climes of France with the baby. As Luc recalled the story, he was struck by the madness of their plan. A middle-aged couple, winter, a newborn? What was in their heads? But the Armistice made people reckless, full of hope for a brighter future.

‘I was moving on instinct,’ Wolf had admitted. ‘You were not our child but no one cared during that time. No one wanted someone else’s newborn, few questions were asked … Everyone just assumed you were our grandchild. I had to get Solange and you away; I wanted you raised as a Frenchman without any attachment to Germany.’ Wolf shrugged. ‘And it all worked out – at least for nearly twenty-five years. Now, it’s your German heritage that may save you.’

Tragedy had struck soon after the fledgling family left Strasbourg. A week after they fled Solange was dead also, knocked over by a bus when Luc was but weeks old.

Until this evening Luc had always believed that Wolf had found him in a barn in eastern France. Clearly his mother had abandoned him, and that had always made it easier to accept his adoption. And yet, in his quiet moments, Luc had wondered at the details. He’d stopped asking questions in his teens, though, as it became obvious the only story he would get was the one he had already been told.

Now Luc had learnt that the old man had walked away from his prestigious university and brought with him a baby. 42Wolf had put as much distance as he could between himself and his past, filled with grief for his wife and Luc’s mother.

Fate had brought Wolf together with a grieving Jacob and Golda Bonet, wealthy French, travelling with their dead infant daughter back to Provence in the depths of the January winter of 1919. Pity and kindness had been shown for the grandfather and grandson, and it was in that train carriage that Wolf had broken his silence and admitted the truth to the Jewish couple. A pact was made, a new baby came into the Bonet family, and Luc’s heritage was hidden as a new background was fabricated.

Wolf had decided that Luc had a better chance of a normal life within a younger family, but he couldn’t bear to be parted from the baby. And so he’d stayed on in Provence, working at the university in Avignon and retiring to a hamlet not far from Saignon. Luc had never known a time without his beloved Wolf.

But how could Luc hold a grudge against his family, the people who had shown him such love, and especially in his greatest hour of need? Luc looked at the lavender in his hand; his saba would be waiting. And this was a family reunion. He was the only son; he needed to defend them. ‘Warian,’ – protect, in Old Frankish – he murmured to himself, and then raised his eyes to the heavens. Wolf had taught him well – now he even thought in different languages.

Germany had killed his real parents. It would not have the parents he loved also. Over my dead body, he thought to himself.

CHAPTER FOUR

Luc’s footsteps resounded on the cobbles of Saignon and he waved to the priest emerging from the church as he strode down the street-lit lane. He had a perfect view of the Bonet home ahead, an imposing triple-storeyed building that sat directly behind the central fountain.

The house was cloaked by evening now, but of an afternoon its pale ochre colour glowed warmly beneath the summer sun and the greyish blue of its shutters and window boxes made a typically bold Provençal contrast. Perhaps he took its simple, exquisite prettiness for granted. And it was only on the rare times he’d been taken to Paris that he’d seen how very lacking in colour a big city was; how lacking it was in the purples and pinks, greens and yellows, oranges and blues of Provence.

To Luc, the Luberon was like a laughing country girl with generous hips, loose hair and the scent of a garden, wearing a colourful dress and a blush at her cheeks. Meanwhile, Paris – oh, Paris was a chic woman with a slightly bemused expression, 44slim-hipped with perfectly cut clothes in conservative dark grey. But she was coquettish – her grand boulevards lined with plane trees, her fabulous gardens and daring monuments, her romantic street lamps. Oh, yes, Paris was more than capable of being playful, yet her demeanour never anything less than graceful. He loved both these women and it hurt his heart to hear that Paris was now draped in huge swastika flags; that those same romantic streetlights were extinguished, and that Adolf Hitler was dressing her in a fearful red and black … the colours of carnage.

Luc was so preoccupied that he nearly walked into the baker. ‘Pardon, Monsieur Fougasse. Forgive me. I was dreaming.’

The grizzled-looking man shrugged beneath a flour sack on his shoulder. ‘We all need dreams, Bonet.’ His voice was surprisingly gentle. Fougasse was a solitary figure. His wife had died early in their marriage and they had been childless. Several of the village women had tried to catch Fougasse’s eye but he kept to himself. He certainly worked hard, baking for many of the villages that didn’t have their own boulangerie.

‘You’re working late, monsieur,’ Luc remarked.

‘There are always people to bake for.’ Fougasse gave a typical Gallic shrug. ‘Someone has to make sure the children get their morning tartines.’