1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

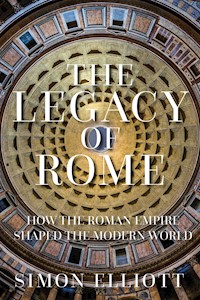

The world of the Roman Republic and Empire is still very much with us, alive and a key companion as we negotiate the trials and tribulations of modern life. We don't just walk in the footsteps of Romans great and small; we walk side by side with them. At its height in the second century AD the Roman Empire stretched across three continents, from Hadrian's Wall in the far north-west to the bustling port cities on the Red Sea, but its influence spread even further afield, with its legacy lasting to this day. In The Legacy of Rome, acclaimed historian Dr Simon Elliott sets off on a grand tour of the whole empire, reviewing each region in turn to show how the experience of being part of the Roman world still has a dramatic impact on our lives today. From wild Britannia, where the legacy of conquest still influences relationships with the Continent; to western Europe, where the language, church and even law can be traced back to antiquity; to schisms and war across central Europe and the Middle East that are directly rooted in the world of Rome – the result is a fascinating exploration of the reach of Rome beyond its borders and through time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

By the same author:

Sea Eagles of Empire

Empire State: How the Roman Military Built an Empire

Septimius Severus in Scotland

Roman Legionaries

Ragstone to Riches

Julius Caesar: Rome’s Greatest Warlord

Old Testament Warriors

Pertinax: The Son of a Slave Who became Roman Emperor

Romans at War

Roman Britain’s Lost Legion: Whatever Happened to legio IX Hispana

Roman Conquests: Britannia

Alexander the Great vs Julius Caesar: Who Was the Greatest Commander in the Ancient World?

Ancient Greeks at War

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Simon Elliott, 2022

The right of Simon Elliott to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9150 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Map

Introduction

1 Troublesome Britannia

2 Germany, Gaul, Spain and Italy: The Imperial Heartland

3 The Danube Frontier, the Balkans and Anatolia

4 The Turbulent East

5 Desert Frontier: Roman North Africa

Conclusion

Appendix A: The Marcomannic Wars

Appendix B: The Battle of Strasbourg

Appendix C: The Carausian Revolt

Timeline of the Roman Republic and Empire

Notes

List of References and Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

Today, going about our daily lives, we are surrounded by real-life legacies of the Roman Republic and Empire, some obvious but most not. In that sense, the world of Julius Caesar, Augustus, Claudius, Diocletian, Constantine I and Justinian I is still with us, extant and engaging. Drawing on specific examples, I aim to show how we still walk step by step with our Roman forebears, the threads of their lives reaching out to us down the years to guide our present.

This is a book about big ideas rather than the usual chronological history. The chapters reflect the breadth of the Republic and the empire’s vast geography, from the far north of Scotland to the Middle East and beyond. The greater part of the book comprises a grand tour of the world of Rome, reviewing each geographic region in turn to show how the experience of being part of the Roman world still dramatically influences the lives of those living there today. I start with far-flung Britannia, the wild west of the Roman world at the best of times. Its never-conquered far north meant this troublesome province required an exceptionally large military presence, while the lengthy campaigns of conquest in the south set in place much of today’s urban landscape and transport network. Meanwhile, how Britain left the Roman Empire in its first ‘Brexit’ at the beginning of the fifth century AD – in a manner very different to the same experience elsewhere in the western empire – helped shape Britain’s differential relationship with its continental neighbours to this day.

Next, I visit the imperial heartlands in the far west of Germany, Gaul, Spain and Italy, where the key pillars of modern society and culture are the direct descendants of their Roman counterparts. The legacy of Rome is often at its most overt here: think of Italian, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese and French, all of which derive from Vulgar Latin and are classified today as Romance languages, as well as Roman law codes and the influence of the Catholic Church. Afterwards, I travel to the north-east of the empire, with the Danube frontier, the Balkans and Anatolia, using a single modern country in the region to show how its Roman heritage is still visible in many walks of life today. My example is Romania, much of which formed the short-lived Roman province of Dacia. Then I consider the history of the great metropolis Istanbul as my example of an urban setting where its Roman origins are still very important. I examine how the later division of the empire into two halves created a schism that still has major implications for the region, with the fault line running through the Balkans.

Moving on, I visit the eastern frontier, where Rome faced off for centuries against the Parthians, and later the Sassanid Persians. There the changing fortunes of the various peoples of the region are again directly linked to the world of Rome. Think of the role Iran’s Persian heritage plays today in its engagement with the western world, and how Rome’s savage suppression of three Jewish Revolts has links with the twentieth-century creation of the modern state of Israel. All are examined in detail in Chapter 4.

Finally, I examine North Africa, super rich powerhouse of the empire where the Roman limes (as the Romans called their fortified frontiers) are still visible in many places on the northern fringes of the Sahara. Having recently travelled extensively in Roman Algeria, I have a real sense of how intensely ‘Roman’ this region was, whether standing in lovely Djémila in the Atlas Mountains or Timgad beneath copper blue skies as I looked south to the soft purple Aures Mountains and the Sahara beyond. In North Africa I use another example of the Roman-built environment, the fabulous ancient city of Leptis Magna in modern Libya, to illustrate how many Roman building techniques are still in use today. I finish this chapter considering the seventh-century AD Arab conquests in the region, to show how their incredible success was facilitated by the pre-existing system of Roman administration, ensuring that this formerly wealthy part of the Roman Empire is now (and has long been) a thriving part of the Islamic world.

In the conclusion I review other, more diverse examples of Rome’s legacy in today’s world, before completing the book with three appendices covering key military campaigns in more depth than was possible in the main text, and finally adding a timeline of key dates in the Roman Republic and Empire for the reader’s reference.

Permanent fortifications are a key feature of this book regarding the legacy of Rome, especially given many modern towns and cities started as such. To describe them I have used the size-based hierarchy now utilised by those studying the armed forces of Rome:

–Fortress, a permanent base for one or more legions. Some were 20ha or more in size, a significant engineering undertaking for the legionaries and other military units of Rome

–Vexillation fortress, a large fort of between 8 and 12ha. Such fortifications held a mixed force of legionary cohorts and auxiliaries

–Fort, a garrison outpost occupied by an auxiliary unit or units. These were between 1 and 6ha in size

–Fortlet, a small garrison outpost large enough to hold only part of an auxiliary unit

In terms of the Roman-built environment, settlement features heavily in the story of the legacy of Rome in the modern world. Here, larger Roman towns are referenced as one of three types. These are: coloniae, chartered towns for military veterans; municipia, chartered towns of mercantile origin; and civitas capitals, the Roman equivalent of a British county town featuring the local government of a region. Settlement below this level is referenced as either a small town (defined as a variety of diverse settlements which often had an association with a specific activity such as administration, industry or religion), villa estates or non-villa estates.

An understanding of Roman social order is equally important. At the very top of the aristocracy was the Senatorial class, said to be endowed with wealth, high birth and ‘moral excellence’. There were around 600 Senators in the mid-second century AD. Those of this class were patricians, a social political rank, with all those below, including other aristocrats, defined as plebeians. Next came the equestrian class, originally comprising those wealthy enough to own cavalry mounts. Members of this class had slightly less wealth but were usually from a reputable lineage. They numbered some 30,000 across the empire in the mid-second century AD. Finally, in terms of the nobility, there was the curial class, with the bar set slightly lower again. The latter were usually merchants and mid-level landowners, making up a large percentage of the town councillors in the Principate Empire. Below the nobility were freemen – free in the sense that they had never been slaves. Freemen included the majority of smaller-scale merchants, artisans and professionals in Roman society.

All of the above were cives Romani, full citizens of the Roman Empire, if they came from Italy. They enjoyed the widest range of protections and privileges as defined by the Roman state and, as such, could travel the breadth of the empire in pursuit of their personal and professional ambitions. Roman women had a limited type of citizenship and were not allowed to vote or stand for public or civil office. Freemen born outside of Italy in the imperial provinces were called peregrini (‘one from abroad’ in Latin) until Caracalla’s Constitutio Antoniniana edict in AD 212, which made all freemen of the empire citizens. As such, in the first and second centuries AD, peregrini made up the vast majority of the empire’s inhabitants.

Further down the social ladder were the freedmen, slaves who had been manumitted by their masters either through earning enough money to buy their freedom or for good service. Once free, these former slaves often remained with the wider family of their pater familias – the head of the family who previously owned them – frequently taking their name in some way. Providing the correct process of manumission was followed, freedmen could become peregrini, though with fewer civic rights than a freeman, including not being able to stand for the vast number of public offices; however, the children of freedmen were automatically freemen. Many freedmen became highly successful, and given they were not allowed to stand for public office, found other ways to celebrate their lives. A common example was the provision of monumentalised funerary monuments, such as that of the baker Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces in Rome. Meanwhile, at the bottom of society were slaves.

This book covers four specific phases of Roman history. The first is the Roman Republic, dating from the overthrow of the Etrusco-Roman king Tarquin the Proud in 509 BC through to the accession of Octavian as the first emperor in 27 BC, when the Senate first acknowledged him as the Emperor Augustus. From this beginning, we talk of the Principate as a period in which the emperor was the leading citizen of the new empire. The name itself derives from princeps (chief or master). While not an official term, later emperors often assumed it on their accession, it clearly being a conceit allowing the empire to be explained away as a simple continuance of the preceding Republic. The Principate Empire featured a number of distinct dynasties:1

–The Julio-Claudian Dynasty, from the accession of Augustus in 27 BC to the death of Nero in AD 68

–The ‘Year of the Four Emperors’ in AD 69, with Vespasian the ultimate victor

–The Flavian Dynasty, from Vespasian’s accession through to the death of his son Domitian in AD 96

–The Nervo-Trajanic Dynasty, from the accession of Nerva in AD 96 to the death of Hadrian in AD 138

–The Antonine Dynasty, from the accession of Antoninus Pius in AD 138 through to the assassination of Commodus in AD 192

–The ‘Year of the Five Emperors’ in AD 193, with Pertinax the first incumbent

–The Severan Dynasty, from the accession of Septimius Severus as the ultimate victor in the ‘Year of the Five Emperors’ through to the assassination of Severus Alexander in AD 235

–The ‘Crisis of the Third Century’, from the death of Severus Alexander to the accession of Diocletian in AD 284

The ‘Crisis of the Third Century’ was a period when the empire was under great stress from a multitude of issues that collectively threatened its very survival. These included civil war and multiple usurpations, the first deep and large-scale incursions into imperial territory by Germans and Goths over the Rhine and Danube, the deadly Plague of Cyprian and the emergence in the east of the Sassanid Persian Empire, which presented the Romans with a fully symmetrical threat there for the first time (even more so than their Parthian forebears). Taken together, these traumatic issues caused a major economic crash. The steps taken by Diocletian to drag the empire out of this chaos, in what is often styled his reformation, were so drastic that, from that point, we talk of the very different Dominate phase of the Roman Empire.

Diocletian’s newly reformed empire now referenced a much more authoritarian style of imperial control, with the name itself based on the word dominus, which meant master or lord in Latin. Gone was the conceit of the Principate with the emperor the principal citizen of the empire but still ‘one of us’. Now, with control of the military and political classes vital to the survival of the empire, he became more akin to an eastern potentate.

There were a number of principal dynasties and time periods in the Dominate phase of empire. The key ones were:2

–Diocletian’s tetrarchy, from his accession in AD 284 until Constantine I secured control of the entire empire in AD 324

–The Constantinian Dynasty, from AD 324 through to the death of Jovian in AD 364

–The Valentinian Dynasty, from the accession of Valentinian I in AD 364 through to the death of the usurper Eugenius in AD 394

–The Theodosian Dynasty, from the accession of Theodosius I the Great in AD 392 until the death of Valentinian III in AD 455

–The Fall of the West, from the accession of Petronius Maximus in AD 455 to the abdication of Romulus Augustulus as the last western emperor in AD 476 on the orders of Odoacor, a senior officer in the Roman army. The latter, leading a revolt of foederates (mercenaries hired on a tribal basis) and regular units, had shortly beforehand been proclaimed rex Italiae, King of Italy. One of his first acts once in power was to send the regalia of western imperial authority to the eastern Emperor Zeno, this officially marking the end of the western empire.

The final phase of Roman history considered here is that covering the narrative of the empire in the east, from the end of that in the west until 1453, when the Ottoman Turks finally sacked Constantinople, destroying the last vestiges of what by then had long been called the Byzantine Empire.

Given the central role often played by events in the Principate phase of the empire, a specific understanding of its geography is important. At this time, the empire was divided into provinces. The word itself provides interesting insight into the Roman attitude to its empire, the Latin provincia referencing land ‘for conquering’. There were two kinds of province in the Principate Roman Empire: senatorial provinces left to the Senate to administer, whose governors were officially called ‘proconsuls’ and remained in post for a year, and imperial provinces retained under the supervision of the emperor. The emperor personally chose the governors for these, and they were often styled legati Augusti pro praetor to officially mark them out as deputies of the emperor.

Senatorial provinces tended to be those deep within the empire where less trouble was expected. At the beginning of the first century AD these were:

– Baetica in southern Spain

– Narbonensis in southern France

– Corsica et Sardinia

– Africa Proconsularis in North Africa

– Cyrenaica et Creta

– Epirus

– Macedonia

– Achaia

– Asia in western Anatolia

– Bithynia et Pontus

I will specifically use ‘proconsul’ to reference the governors of these Senatorial provinces, and ‘governor’ to reference this position in an imperial province.

A further comment on terminology. The words ‘German’ and ‘Goth’ are frequently used, confusingly perhaps, given that the Goths themselves were of German descent. Both words are problematic because they infer a very loose tribal identity at best. While each grouping may have often shared the same blood and cultural practices, the tribes within more often fought with themselves than the Romans, and indeed, later provided many of the troops and military leaders in the Dominate Roman army. Even the term ‘tribe’ itself is problematic because many were confederations of various regional groupings, often incorporating many non-Germanic peoples. While acknowledging these issues, I retain the use of the words here for ease of reference, especially given they were terms well understood by the Romans.

Lastly, I would like to thank those who have helped make this book of big, often deliberately challenging ideas regarding the Roman world and its relationship with our world today possible. Firstly, as always, Professor Andrew Lambert of the War Studies Department at KCL, Dr Andrew Gardner at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology and Dr Steve Willis at the University of Kent. All continue to encourage my research on the Roman military. Also Professor Sir Barry Cunliffe of the School of Archaeology at Oxford University, and Professor Martin Millett at the Faculty of Classics, Cambridge University. Next, my patient proofreader and lovely wife Sara, and my dad John Elliott and friend Francis Tusa, both companions in my various escapades to research this book. As with all of my literary work, all have contributed greatly and freely, enabling this work on the legacy of Rome to reach fruition. Finally, I would like to thank my family, especially my tolerant wife Sara once again, and children Alex (also a student of military history) and Lizzie.

Thank you all.

Dr Simon ElliottFebruary 2021

1

TROUBLESOME BRITANNIA

As you exit Tower Hill tube station in the City of London, to the left stands the largest surviving section of Roman London’s land wall. Over 10m in height, it soars enigmatically over commuters and tourists, many of whom pass by oblivious to its unlikely story. The wall, one of the few constants in an ever-changing city, is built from courses of grey-green Kentish ragstone blocks. These were quarried 127km away to the east in the upper Medway Valley by the Classis Britannica Roman navy before being transported down the Medway and up the Thames. Every few courses the grey-green stones are interrupted by striking bonding layers of flat orange tile. These were designed by the Romans to give the wall flex in case of an earthquake.

Few think it beautiful, but I do. Even fewer know it dates back to the great warrior Emperor Septimius Severus. Hacking his way to power in the ‘Year of the Five Emperors’ in AD 193, he soon had to fight off the challenge of the usurping British governor, Clodius Albinus. The pair clashed at the titanic Battle of Lugdunum (modern Lyon) in Gaul in AD 197. This was the largest recorded civil war battle in Roman history, with 200,000 men engaged. Severus won, only just, after two days of brutal fighting. Albinus was beheaded, his body trampled by Severus on his stallion.

The emperor’s next action was to send military inspectors to Britain to bring the recalcitrant province back into the imperial fold. Their first act was to build the enormous land walls of London. This took over 420,000 man-days to complete, needing 45,000 tonnes of ragstone for the facing alone.1 They were designed not to keep out an external threat, but to send the elites and citizens of the provincial capital a blunt message: behave or else. Such is a prime example of the legacy of Rome in this farthest north-western corner of empire, the wall circuit that defines the City of London – the Square Mile – to this very day. A relic to a failed usurper.

There are many examples of the Roman legacy in Britain, some visible above the surface, some below it, and some purely cultural. Rome’s legacy here actually manifests in three very specific ways. First, much of the modern built environment and transport infrastructure is a direct result of the Roman occupation. Think of the provincial capital London with the striking Severan example above, the many towns and cities that were originally the site of a Roman fortress or fort, and the pre-motorway trunk road network. This is specifically linked to the laborious and lengthy campaigns of conquest here that lasted over forty years, far longer than in other parts of the empire. Second, as part of this process the far north and Ireland were never conquered, despite at least two intense efforts regarding the former. This set in place the political settlement of the islands of Britain that exists to this day. Third, the catastrophic way the later diocese of Britannia left the empire in the early fifth century AD. Today, many believe Britain a place of difference in Europe, as evidenced by the fierce debate when Britain exited the European Union. Few realise this sense of variance dates back directly to the end of Roman rule in Britain.

Town and Country

An understanding of pre-Roman Britain is important to appreciate the empire’s later legacy. Repopulation after the last Ice Age began around 9600 BC.2 Those arriving were hunter-gatherers, part of the Upper Paleolithic Ahrensburgian culture that stretched from the Atlantic coast to Poland, later to be replaced by various European Mesolithic cultures.

Around 6500 BC, a dramatic event then occurred that has defined Britain geographically ever since. This was the final submergence of Doggerland, the North Sea land-bridge linking Britain to the continent. However, the islands remained culturally connected to mainland Europe, with Britain continuing to participate in each new wave of social and technological advancement. This included farming, which arrived with the onset of the Neolithic period around 4200 BC, the Copper Age from 3000 BC and the Bronze Age from 2500 BC. The latter coincided with the appearance of the Bell Beaker culture that linked the islands of Britain with every corner of the European landmass, including the Mediterranean. Archaeological evidence from this period, including the Amesbury Archer buried near Stonehenge (who most likely originated in Switzerland), shows that Britain was fully engaged in long-range European trading networks spanning far and wide across the continent, with the English Channel and North Sea certainly no barrier but a place of connectivity. A Bronze Age boat dating to 2500 BC, discovered in Dover in 1992 and now displayed in the town museum, dramatically shows this, given it was clearly employed to facilitate regular maritime trade with mainland Europe.

The British Iron Age followed from around 800 BC, with Britain again fully participating in the ensuing Hallstatt culture and its later La Tène development. The latter peaked in Britain around 100 BC with the onset of the Late Iron Age, setting the scene for the arrival of Rome.

Prior to Gaius Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul in the 50s BC, little was known in the Mediterranean world about the islands of Britain. Native Britons were first referenced by the fourth-century BC geographer Pytheas of Massilia, who circumnavigated the islands during an extensive maritime exploration.3 He called them the Pretani, meaning painted ones, referencing a tattooing or woad skin-painting tradition among some of the local tribes. This was the origin of the later name Britain. Later geographers and merchants added details such as the shadowy Druidic cults and readily available extractive raw materials. The latter included iron,4 tin, silver and gold. Britain was also known for its exports of woollen goods, hunting dogs and slaves, though whether any of these reached the markets of the Mediterranean is doubtful. Otherwise, it remained a fearful place to the Romans, its islands shrouded in mystery, and across terrifying Oceanus, as they called the seas outside of the Mediterranean.

During the Late Iron Age, Britain remained intimately connected with pre-Roman Gaul, with key tribes sharing names with counterparts on the continent. These included the Belgae, on the south coast; Atrebates, in the Thames Valley; and Parisii, above the Humber. Cross-Channel exporting continued to flourish too – for example, the very fine greensand millstones and quern stones manufactured by a thriving industry at East Cliff in Folkestone.

From 58 BC, this connectivity was brutally dislocated by Caesar’s Gallic wars. From that time onwards Britain became a place of refuge for those fleeing his bloody campaigns on the continent. Plutarch later calculated that these campaigns cost the lives of 1 million Gauls and the enslavement of another million.5 To contextualise the scale of this loss, the entire population of Britain at this time was 2 million.6 This level of carnage and slaughter might explain the comparative ease with which Gaul was incorporated into the empire. Suddenly, Britain’s umbilical connection with continental neighbours of like mind and culture had been shut off. From that moment, the tribes in Britain found themselves dealing with Romans casting an avaricious eye across the English Channel. They were soon to arrive.

Caesar’s two incursions into Britain in 55 and 54 BC were set firmly within his campaigns of conquest in Gaul. This in itself is a striking example of how closely Britain and pre-Roman Gaul were perceived to be linked. Caesar had three key reasons for invading. First, Britain remained a source of trouble on the north-western flank of his conquests in Gaul. Second, Caesar was always on the lookout for an opportunity to make money, and knew of Britain’s exploitable natural resources. Finally, Caesar was never one to pass the chance for new glory, with Britain being the ultimate challenge.

It is hard to explain to a modern audience what a truly fantastical adventure Caesar planned. In the first instance, his force would have to cross Oceanus. Such a voyage was a frightful proposition to sailors and legionaries used to the comparatively benign Mare Nostrum, as the Romans called the Mediterranean. Then, as detailed, once in Britain he would be campaigning in a land of which the Romans knew little. This was truly a leap in the dark.

His first invasion in 55 BC was a resounding flop, though he attempted to gloss over the failures in a self-promoting narrative. His fleet, carrying 12,000 legionaries, had to fight a contested landing on the east coast of Kent that could have just as easily gone against the Romans. Next, the failure of his cavalry to arrive meant he was unable to pursue his defeated foe, or carry out reconnaissance to support any further advance. In the event, hampered by bad weather that damaged many of his ships, he got little further than his beachhead marching camp and soon returned home.

Showing typical Roman grit, Caesar determined to return the following year. This time he had a much greater force of 30,000 men and 2,000 allied cavalry. The enormity of this army intimidated the Britons, who avoided opposing Caesar’s landing, again on the east coast of Kent. Despite bad weather again damaging his ships, this campaign was far more successful. Soon Caesar’s legionary spearheads had crossed the River Thames and captured the main base of the British leader, Cassivellaunus. The latter sued for peace and terms were quickly agreed. These included the Britons supplying hostages and agreeing to pay an annual tribute to Rome. Honour satisfied, Caesar then withdrew back to Gaul.

While limited in their success, Caesar’s two incursions put Britain firmly on the Roman map – especially his second 54 BC campaign. Never again would these islands be left to their own devices. From that point on, contact between Rome and the Britons increased, but this was not the relationship of equals the latter had enjoyed with their continental neighbours before Caesar’s conquest of Gaul.

Roman plans to revisit Britain started early. Augustus himself, founder of the empire, considered three invasions in 34, 27 and 25 BC. The first and last were abandoned because of issues in the Mediterranean, the second was cancelled after some hasty diplomacy. Such false starts were certainly viewed negatively, as the first-century BC poet Horace reflected: ‘Augustus will be deemed a God on Earth (only) when the Britons and the deadly Parthians [also targets for early Imperial Roman expansion] have been added to our empire.’7

In AD 40, Caligula abandoned an invasion of Britain despite having got as far as the beaches of northern Gaul, building 900 ships and stocking warehouses with supplies. It was left to the ill-favoured Claudius to carry out an invasion of Britain with a true intention to stay. Having become the most unlikely of emperors at the hands of the Praetorian Guard in Rome in AD 41 after the assassination of Caligula, he was determined to secure his legacy through conquest. Opportunity was provided by the death of Cunobelinus, king of the Catuvellauni, whose territory covered much of the south-east of Britain above the River Thames. His sons Caratacus and Togodumnus succeeded him, immediately launching an offensive against their Atrebates neighbours in the Thames Valley, whom they defeated in short order. These were long-standing allies of Rome and their king Verica fled to seek the protection of Claudius. Caratacus and Togodumnus then overplayed their hand, demanding the king’s extradition. Claudius refused, with disturbances following in Britain against Roman merchants who had been embedded there since Caesar’s incursions. The emperor already had the means available, thanks to Caligula and his ships and warehouses, and now he had the opportunity. He decided to invade.

Given the enormity of the task, Claudius took no chances. He appointed the highly experienced Aulus Plautius to command his army of conquest, the Pannonian governor being a close family friend (Pannonia was, broadly, modern western Hungary and eastern Austria). This comprised four legions (legio II Augusta, legio IX Hispana, legio XIV Gemina and legio XX Valeria Victrix) which, together with their associated auxiliaries, formed an army of 40,000 men. This enormous force sailed in three divisions and landed unopposed in late summer on the east coast of Kent near Richborough (later Roman Rutupiae). Once ashore, Plautius secured the beachhead by building a huge 57ha marching camp, the remains of which can be seen today within the wall circuit of the later Saxon Shore fort in the form of two enormous ditches and a gateway.

The Roman breakout soon began, with Plautius quickly defeating Caratacus and Togodumnus in two small engagements in eastern Kent. He then fought a major battle at a river crossing often identified as Alyesford on the Medway.8 This two-day affair was close-run, with the Romans unable to deploy their fleet in support as the site was above the river’s tidal reach. Finally victorious, Plautius then chased the fleeing Britons to the Thames, where they again failed to stem the Roman advance. Once in what is today Essex, Plautius paused to consolidate, there learning that Togodumnus was dead and Caratacus had fled west to find sanctuary in Wales. Regrouping for a final push, he then sent for Claudius to join him to share the final victory. The emperor quickly crossed the Channel, arriving at Plautius’ camp with elephants and camels (probably from the imperial menagerie), which he hoped would intimidate the native Britons. The force then broke camp and headed north at speed for the Catuvellaunian capital of Camulodunum (later Roman Colonia Claudia Victricensis, modern Colchester), arriving in late October. This lightning strike eviscerated all before it and the Catuvellauni quickly sued for peace, eleven other British tribes following suit soon after. Claudius declared the province of Britannia founded, established Camulodunum as its capital and appointed Plautius its first governor. He then left, never to return, having stayed for only sixteen days.

Up to this point the conquest of Britain had followed a similar pattern to that of Gaul, leaving little evidence on the landscape of modern Britain. This soon changed. It took Caesar only eight years to pacify Gaul. It took the Romans another forty-two years to finally establish a northern border in Britain, along the Solway Firth–Tyne divide. Thus, from the very point of Claudius’ successful declaration of victory, Britain was set on a very different path to the other continental provinces, with the campaigns of conquest a gruelling process that left a lasting imprint on the urban and rural landscape.

Claudius’ new province only covered the south-east of England, and his legions set off immediately to expand it. They travelled along river systems wherever possible for ease of supply. First, legio XX Valeria Victrix built a fortress at Colchester. The three remaining legions then set off in different directions.

Plautius’ own legio IX Hispana headed north, skirting the territory of the Iceni tribe in modern Norfolk and reaching the River Nene, where it established a vexillation fort (a single rampart), thus founding the modern village of Longthorpe near Peterborough. It then continued north to build another vexillation fort on the River Soare, the basis of modern Leicester (Roman Ratae Corieltauvorum), before reaching the River Witham, where it built a full legionary fortress where the city of Lincoln is now situated (Roman Lindum Colonia). Meanwhile, legio XIV Gemina headed deep into the Midlands, establishing a vexillation fort on the River Cam and founding modern Great Chesterford (Roman name unknown), another on the River Anker, founding modern Mancetter (Roman Manduessedum), and finally another on the River Alne founding modern Alcester (Roman Alauna).

Most famously, legio II Augusta under the future Emperor Vespasian (AD 69 to AD 79) struck out for the south-west, where the tribes were notably hostile. The historian Suetonius goes into great detail here, telling us that Vespasian ‘fought 30 battles, subjugated two warlike tribes, captured more than 20 oppida, and took the Isle of White’.9 The tribes Suetonius mentioned were the Durotriges and Dumnonii, their oppida fortified native urban centres. Meanwhile, Vespasian’s key founding was modern Exeter, initially a wooden vexillation fort and later a legionary fortress which became the Roman town of Isca Dumnoniorum. Today, the Roman legacy in the region lives on, given Exeter is the principal administrative centre and county town of Devon.

Plautius returned to Rome along with Vespasian in AD 47. By then Britannia comprised the region below a line from the River Severn to the Wash, excepting the client tribes of the Atrebates in the Thames Valley and the Iceni in northern East Anglia. The next governor was Publius Ostorius Scapula. He campaigned in Wales against raiders led by Caratacus (founding Gloucester as a vexillation fort, Roman Glevum), put down an early rebellion by the Iceni, and fought the Brigantes in the north.

Ostorius was replaced by Didius Gallus in AD 51, who also campaigned in Wales, followed by Quintus Veranius Nepos in AD 57, who died within a year. The next leader was one of the truly great British governors, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. Soon after arriving he targeted Anglesey at the north-western tip of Wales, deep in the heart of Deceangli territory.10 This mysterious island was home to the Druids. Paulinus staged a major amphibious assault here in AD 60, capturing the island after a vicious battle.

Next, the province faced an existential threat from a totally unexpected direction. This was the AD 60/61 revolt of Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni. The context was the earlier death of Boudicca’s husband, the Iceni king, Prasutagus. An ally to Rome, in his will he left his kingdom to his daughters and also the Emperor Nero. When he died, the Romans predictably ignored his will and annexed the kingdom. Boudicca protested but was flogged, with her daughters allegedly raped, though another factor was Roman financiers calling in their loans to the British elites there.

Soon Boudicca’s incendiary rebellion had ignited most of the south-east above the Thames against the Romans. Marching south at the head of an army 100,000 strong, she torched Colchester, then the early emporium of London (Roman Londinium) and finally St Albans (Roman Verulamium). Dio says that, in total, 80,000 Romans and Romano-British were massacred.11 Hearing the news, Paulinus rushed south-east and, despite being heavily outnumbered, forced a meeting engagement north of St Albans. Here he won a famous victory, massacring the rebels. Boudicca took her own life.

Paulinus’ success came at the cost of great loss of manpower, and his next move was to draft in 2,000 more legionaries, 1,000 auxiliary cavalry and eight units of auxiliary foot from Germany to reinforce the province. The Romans had been badly rattled. I believe that if Paulinus had lost his battle the whole province would have fallen, the Romans never to return. Instead, from that point onwards London became the provincial capital, setting it on its track to becoming a commercial powerhouse by the end of the first century AD.

Consolidation followed, with the slow process of northward conquest not beginning again until AD 69 when the new governor, Marcus Vettius Bolanus, campaigned against Brigantes in the north. Here Queen Cartimandua, a Roman ally, had been usurped by her estranged husband Venutius. Though Bolanus achieved some success, he was replaced from AD 71 by the first of three great warrior governors. This was Quintus Petillius Cerialis, with orders from Vespasian to achieve military glory for the new Flavian Dynasty, whose founder Vespasian had been declared emperor two years earlier. Tacitus states that Cerialis headed north immediately, ordering legio IX Hispana from Lincoln to the River Ouse, where they built a new legionary fortress, founding York (Roman Eboracum).12 At the same time, legio II Adiutrix was sent to the River Dee where a new naval facility and fort (later fortress) was built, founding Chester (Roman Deva Victrix). When all was ready, Cerialis then launched a savage offensive, with legionary spearheads from legio XX Valeria Victrix and legio IX Hispana driving up the north-west and north-east coasts, supported by the Classis Britannica regional fleet. As the campaign unfolded a multitude of vexillation forts were built, with the Brigantes finally crushed and Venutius killed. By the time Cerialis returned to Rome in AD 74, the north of England had been incorporated into the province, though the fate of Cartimandua is unknown.

The next warrior governor was Sextus Julius Frontinus, another Flavian favourite. Arriving in Britain with the north now pacified, Frontinus turned his attention to the unfinished business in Wales. Here, in spite the campaigns of Gallus, Nepos and Paulinus, the native tribes were still troublesome. Deploying legio II Augusta from its base in Gloucester, Frontinus launched a campaign that took three years to defeat the tribes of southern and central Wales. To secure the region, he then redeployed the legion from Gloucester to the River Usk, where they built a large legionary fortress, founding modern Caerleon (Roman Isca Augusta), 8km upstream of what is now the city of Newport. As a final act while governor, he also campaigned against the Brigantes, indicating more trouble in the north.

The Roman occupation of the growing province was slow and painful. Because of the need to physically lock down newly occupied areas with forts large and small along campaigning stop lines, the legacy of Roman conquest is still physically written across today’s landscape. The system of fortifications was linked by a series of military trunk roads that form the backbone of the pre-motorway road network in Britain. Think of the modern A2, which follows the line of Watling Street from the Imperial Gateway at Richborough on the east Kent coast through to modern Southwark. Watling Street then turns north to cross the Thames, broadly on the line of London Bridge. It then enters the provincial capital, continuing north to the basilica and forum beneath modern Leadenhall Market, before turning west, exiting the city at Aldersgate. It becomes, in turn, the modern City Road, Euston Road and the A5, all the way to Wroxeter (Roman Viriconium) in the Welsh Marches. There it branches north to the legionary fortress at Chester and south to the legionary fortress at Caerleon.

Similarly, the Fosse Way, for much of its length the modern A46, links the legionary fortress at Lincoln through the fort at Leicester to the legionary fortress at Exeter. Meanwhile, Ermine Street links the provincial capital of London with the legionary fortress at Lincoln, and then that at York. From there, Dere Street extends this route north into the Scottish Borders. The modern A1 follows the line of both for much of its length before the A68 picks up Dere Street as it crosses Hadrian’s Wall.

Other key Roman roads in Britain, their routes still in use today, served different purposes. The modern A229 in Kent was originally built as an administrative road linking Rochester (Roman Durobrivae) with the ragstone quarrying metalla in the upper Medway Valley (which provided much of the stone to build Roman London) and the iron metalla (industrial scale quarrying and mining enterprises, often run by the state) in the Weald.13

In addition, there was the systematic use of waterways by the Romans, whether the river systems as already detailed, new canals, or the littoral seaways around the coast. This too has left its legacy in the built environment of modern Britain. For example, Rochester is a Roman founding at the point where Watling Street crossed the Medway, while in the north all of the modern towns and villages along Dere Street mark the crossing points of regional waterways, originally founded as vexillation forts with their associated vici, or civilian settlements. Examples include Aldborough (Roman Isurium Brigantum) on the River Ure, Catterick (Roman Cataractonium) on the River Swale, Piercebridge (Roman name unknown) on the River Tees, Binchester (Roman Vinovia) on the River Wear, Ebchester (Roman Vindomora) on the River Derwent and Corbridge (Roman Coria) on the River Tyne.14 Newcastle-upon-Tyne is another example in the region, founded as Pons Aelius (Hadrian’s Bridge) at the point where the Roman Cades’ Road from Brough-on-Humber (another Roman founding, then called Petuaria) to Chester-le-Street (also Roman, then known as Concangis) crossed the Tyne.

Many of the rivers in Britain were fully canalised by the Romans, with their banks cleared of all vegetation above their tidal reaches to allow the use of sails and then covered in compacted sand to enable the towing of codicaria river barges. The fourth-century AD Roman poet Ausonius gives insight to this exact process.15 Some rivers even had complex sequences of locks and weirs, for example in the upper Medway Valley to provide riverine access to the ragstone quarries there.16

Many of the major canals built by the Romans still exist in some form. The best example is the 122km-long Car Dyke in East Anglia. Here, in addition to the construction of the waterway, recent research has identified at regular intervals along its length gravel causeways on timber pile foundations at a depth of 1m. These were laid during the canal’s construction to facilitate crossing points for local trackways.

The legacy of Roman maritime transport is also evident around the coasts of modern Britain, which featured thriving trade routes up both the west and east coasts and to the continent. Key ports, all Roman foundings and which all also featured forts, included Cardiff (Roman name unknown), Lancaster (Roman name unknown), Maryport (Roman Alauna) and Bowness-on-Solway (Roman Maia) on the west coast, and Dover (Roman Dubris) and South Shields (Roman Arbeia) on the east.

Meanwhile, the Romans viewed the North Sea and English Channel as a point of connectivity with the continent rather than a barrier, just as the Britons had before their arrival. The latter view has its roots in the past few hundred years of political and military history (think of Hitler’s abortive Operation Sea Lion to invade Britain), but for the Romans these waterways were the essential means of ensuring Britannia remained a fully functioning part of the empire, even if a troubled province.

The Far North and Ireland

The task of formalising Rome’s northernmost frontier was left to the last and greatest warrior governor, Gnaeus Julius Agricola. Having previously commanded legio XX Valeria Victrix, he was already familiar with the troublesome province. Returning as governor in the late summer of AD 77, he immediately launched a savage offensive against the Ordovinces in response to the near annihilation of a Roman cavalry detachment. Within a month he’d hacked his way through to rebellious Anglesey, finally destroying any further opposition there.

Encouraged by Vespasian to greater glory, Agricola now turned his gaze to the far north. In AD 78 he redeployed his legions to the former territory of the Brigantes, spending a year pacifying any remaining resistance and building a string of forts to secure his rear. These included those at Manchester (Roman Mamucium) and Carlisle (Roman Luguvailium), both Roman foundings, and those along Dere Street.17 In AD 79 he launched an assault into the Scottish Borders. This followed the same pattern Cerialis had used against the Brigantes, with legionary spearheads forging up the west and east coasts supported by the Classis Britannica. Success is indicated by the building of a substantial fort at Newstead on the River Tweed (Roman Trimontium), site of the Selgovae tribe’s capital. Tacitus adds that the eastern spearhead may have reached as far north as the River Tay above Fife. Certainly Agricola’s accomplishments were well regarded in Rome, with Dio adding that the new emperor, Titus, was given his fifteenth salutation by way of celebration.18

Agricola spent AD 80 consolidating his position in the Scottish Borders and Fife, constructing new military harbours to forward deploy the Classis Britannica. Examples include Kirkbride, Newton Stewart, Glenluce, Stranraer, Girvan, Ayr and Dumbarton on the west coast, and Camelon on the east. A major naval base may also have been established at Carpow on the Tay. Today, all are key regional harbours, another legacy of Rome.

In his third year of campaigning, in AD 81, Agricola targeted the south-west of the Scottish Borders where the Novantae tribe had proved particularly difficult to pacify. For this he launched an amphibious assault, with himself in the lead ship. This was either northwards across the Solway Firth, or westwards across the River Annan in Galloway. Again, he achieved total success.

Next, Tacitus says Agricola considered invading Ireland late in the campaigning year with one legion.19 He certainly had the means, given much of the Classis Britannica was already deployed in the north-west for his campaign against the Novantae. Gathering in Loch Ryan or Luce Bay in Galloway, this fleet would only have to travel 32km to reach Belfast Lough. However, the invasion never took place, due to the new emperor refusing permission.20 Domitian (AD 81 to 96) had little interest in far-off Britannia, with his principal focus being the Danubian frontier. His decision set in place the political settlement between the two largest islands of Britain that exists to this day.

With new imperial orders, Agricola headed north in AD 82. This time the legionary spearheads forged above the Clyde and Forth line, focusing on the east coast, given the inhospitable terrain in the west. The native Britons here, collectively called the Caledonians, began to fight for their very survival. Tacitus describes them attacking Roman military installations in desperation, including Rome’s most northerly legionary fortress at Inchtuthil on the Tay.21 Agricola once more prevailed, the campaigning season ending with the Romans poised for one final assault on the farthest north.

Agricola fielded 30,000 men for his fifth and final campaign, in AD 83. He was not taking any chances. First he sealed off the east coast with the Classis Britannica, then he launched his huge force north towards the Grampians and Moray Firth. His aim was to force the Caledonians into a decisive meeting engagement. In this he succeeded, the gathered tribes offering battle at a place called Mons Graupius. While the exact location isn’t known, the outcome is. The Caledonians were massacred in a total Roman victory.