Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

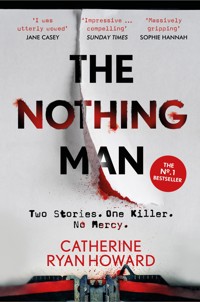

· · THE IRISH TIMES AND KINDLE No. 1 BESTSELLER · · Shortlisted for the CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger 'I cannot put it down!' Georgia Hardstark, MY FAVORITE MURDER I was the girl who survived the Nothing Man. Now I am the woman who is going to catch him... You've just read the opening pages of The Nothing Man, the true crime memoir Eve Black has written about her obsessive search for the man who killed her family nearly two decades ago. Supermarket security guard Jim Doyle is reading it too, and with each turn of the page his rage grows. Because Jim was - is - the Nothing Man. The more Jim reads, the more he realises how dangerously close Eve is getting to the truth. He knows she won't give up until she finds him. He has no choice but to stop her first... 'The queen of high-concept crime fiction... I was utterly wowed' - Jane Casey 'Whipsmart, thrilling and utterly compelling' - Liz Nugent Readers love THE NOTHING MAN 'Up there as one of the best plots ever' ***** 'Brilliant concept, brilliantly executed' ***** 'Clever. Original. Engaging read' ***** 'I haven't read anything like this before and it worked so well' ***** 'Dark, stunning and absolutely chilling' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 459

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Catherine Ryan Howard

Distress Signals

The Liar’s Girl

Rewind

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Catherine Ryan Howard, 2020

The moral right of Catherine Ryan Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 8389 5106 1

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 659 1

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 660 7

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To John and Claire, who have to share,because to put one before the other just wouldn’t be fair.

Jim was on patrol. Head up, eyes scanning, thumbs hooked into his belt. The heft of the items clipped to it – his phone, a walkie-talkie, a sizeable torch – pushed the leather down towards his hips, and the weight of them forced him to stride rather than walk. He liked that. When he got home at the end of the day and had to take off the belt, he missed the feel of it.

The store had only opened thirty minutes ago and the staff still outnumbered the customers. Jim circled the Home section, then cut through Womenswear to Grocery. There was at least some activity there. You could count on a handful of suited twenty-something males to come darting around the aisles round about now, eyes scanning for the carton of oat milk or pre-packed superfood salad they were after, as if they were on some sort of team-building task.

Jim stared into their faces as they rushed past, knowing they could feel the heat of his attention.

He made his way to the entrance, where the department store met the rest of the shopping centre beyond. He watched people coming and going for a few minutes. He checked the trolleys, all neatly lined up in their bay. He paused at the bins of plastic-wrapped bouquets to dip his head and breathe in deep, getting a whiff of something floral and something else faintly chemical.

One of the bins appeared to be leaking water on to the floor underneath. Jim pulled his radio off his belt and called it in. ‘We need a clean-up by the flowers. Possible leaking bin. Over.’

He waited for the crackle of static and the drawl of the bored reply.

‘Copy that, Jim.’

This time of the morning he liked to have a surreptitious read of the headlines. He moved to do that next. But before he reached the newspapers he saw, in his peripheral vision, someone duck behind the carousel of greeting cards about fifteen feet to his right.

Jim didn’t react, at least not outwardly. He continued with his plan, walking to the far side of the newspaper display so that he could face the cards. He picked up a paper at random and held it out in front of him. He looked at its front page for a beat and then slowly raised his gaze.

A woman. For this time of the morning, she looked the part. Trench coat on but not buttoned up, large leather handbag resting in the crook of one arm, stylish but functional shoes. A harried look. A young professional on her way to work, trying to knock one thing off her endless list of ‘Things To Do’ before she had to go into the office and do more of them – or maybe that’s just what she wanted you to think. There was something tucked under her left arm. Jim thought it might be a book.

A ding-dong sound interrupted the quiet muzak playing throughout the store before a disembodied voice boomed, calling someone named Marissa to Flowers. That’s Marissa to Flowers, please; Marissa to Flowers.

The woman picked one of the cards and looked at it as if it was the most interesting thing she’d ever seen in her life.

Jim had the newspaper held up high. If she looked at him from this angle she would see the grey hair and the age-spotted hands, but not the ID hanging from his shirt pocket that said SECURITY in bright red lettering.

The book slipped out from under her arm and fell to the floor with a smack. She reached down—

The Nothing Man.

The words were printed in a harsh yellow across the book’s black, glossy cover.

As she bent down and picked it up, Jim could see the same three words on its spine too.

Blood suddenly rushed into his ears in a great, furious wave, filling his head with white noise. It had an underlying rhythm to it, almost like a chant.

The Nothing Man The Nothing Man The Nothing Man.

He was dimly aware of the fact that the woman was now looking at him, and that it looked like he was probably staring at her. But he couldn’t pull his eyes from the book. He was rooted to the spot, deafened by the chant that was growing louder all the time, only moments away from becoming a full-blown, wailing siren.

THE NOTHING MAN THE NOTHING MAN THE NOTHING MAN.

The woman frowned at him, then moved away in the direction of the tills.

Jim didn’t follow to check that she was actually going to pay for the book, which he might have done under normal circumstances. Instead, he turned and walked in the opposite direction, towards the aisle where they stocked the stationery supplies, a small selection of children’s toys and the books.

It’s fiction, he told himself. It has to be.

But what if it wasn’t?

He didn’t have to search. Three entire shelves were taken up with its display. Every copy was facing out. A dark chorus, screaming at him.

Pointing at him.

Accusing him.

They hadn’t been there yesterday, Jim was sure. The stock must have come in overnight. It must be a new book, probably just released this week. He stepped closer to look for the author name—

Eve Black.

To Jim, that was a twelve-year-old girl in a pink nightdress standing at the top of the stairs, peering down into the dim, saying ‘Dad?’ uncertainly.

No. It couldn’t be.

But it was. It said so right there on the cover.

The Nothing Man: A Survivor’s Search for the Truth.

Jim felt a heat spreading inside him. His cheeks flushed. His hands shook with the duelling forces of his desperately wanting to reach for the book and the part of his reptilian brain trying to stop him from doing it.

Don’t do it, he told himself, just as he reached out and took one of the books from the shelf.

The hard cover felt smooth and waxy. He touched the title with his fingertips, feeling the letters rising to meet his skin.

The Nothing Man.

His other name.

The one the newspapers had given him.

The one no one knew belonged to him.

Jim turned the book over in his hands.

He came in the night, into her home. By the time he left, only she was left alive … The sole survivor of the Nothing Man’s worst and final attack, Eve Black delves deep into the story of the monster who terrorised Cork City, searching for answers – and searching for him.

After all this time …

That little fucking bitch.

Jim opened the book. Its spine cracked loudly, like a bone.

First published in the UK and Ireland by Iveagh Press Ltd, 2019

Copyright © 2019 by Eve Black

IVEAGH PRESS IRELAND LTD

42 Dawson Street

Dublin 2

Republic of Ireland

Material covered in The Nothing Man was featured in the article ‘The Girl Who’ first published by the Irish Times.

The author and publishers have made all reasonable efforts to contact copyright-holders for permission, and apologise for any omissions or errors in the form of credits given. Corrections may be made to future printings.

The right of Eve Black to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 987-0-570-34514

For Annaand all the victims whose names we tend to forget, or never learn

THE VICTIMS

Alice O’Sullivan, 42,

Physically assaulted in her home on Bally’s Lane, Carrigaline, Co. Cork, on the night of 14 January, 2000.

Christine Kiernan, 23,

Sexually assaulted in her home in Covent Court, Blackrock Road, Cork, on the night of 14 July 2000.

Linda O’Neill, 34,

Violently and sexually assaulted in her home outside Fermoy, Co. Cork, on the night of 11 April 2001.

Marie Meara, 28, and Martin Connolly, 30,

Murdered in their home in Westpark, Maryborough Road, Cork, on the night of 3 June 2001.

Ross Black, 42, Deirdre Black, 39, and Anna Black, 7,

Murdered in their home in Passage West, Co. Cork, on the night of 4 October 2001.

The author was the lone survivor.She was aged 12 at the time.

A Note on Sources

There are three sides to every story, they say: yours, mine and the truth. At the time of writing, the Nothing Man has not yet told his. Transcripts, reports, recordings and in-person interviews are as close as we can get to hard facts, and I have relied on them exclusively as sources for this book. I have made every effort to tell other people’s stories – those of his victims, those of the man who tried to stop him – as accurately as possible. But this is also my story. I have done my best to tell it to you as I tell it to myself. That, I think, is as close as we can get to the truth.

INTRODUCTION

The Girl Who

When we meet, I probably introduce myself to you as Evelyn and say, ‘Nice to meet you.’ I transfer my glass to my other hand so I can shake the one you’ve offered, but the move is clumsy and I end up spraying us both with droplets of white wine. I apologise, perhaps blush with embarrassment. You wave a hand and protest that no, no, it’s fine, really, but I see you snatch a glance at your shirt, the one you probably had dry-cleaned for the occasion, to surreptitiously assess the damage. You ask me what I do and I don’t know if I’m disappointed or relieved that this conversation is going to be longer. I say, ‘Oh, this and that,’ and then ask what you do. You tell me and I make the mmm sounds of polite interest. There’s a silence then: we’ve run out of steam. One of us rushes to use the last remaining card in play: ‘So, how do you know …?’ We take turns explaining our social ties to the host, casting for connections. We probably find some. Dublin is a small place. We grasp for other topics: the turnout tonight, that podcast everyone is obsessed with, Brexit. The room is uncomfortably warm and noisy and strange bodies brush against mine as they pass, but the real source of my anxiety, the thing that has an angry red flush flaring up my neck, is the possibility that, at any moment, the penny will drop, and you’ll frown and cock your head and look at me, really look at me, and say, ‘Wait, aren’t you the girl who …?’

This is always my fear when I meet someone new, because I am.

I am the girl who.

I was twelve years old when a man broke into our home and murdered my mother, father and younger sister, Anna, seven years old then and for ever. I heard strange and confusing sounds that I would later discover were my mother’s rape and murder and my sister’s asphyxiation. I found my father’s bloody and battered body in a crumpled heap at the bottom of the stairs. I believe that, having survived the attack, he was trying to get to the phone in our kitchen so he could raise the alarm. I survived because of my bladder, because of the can of Club Orange I’d smuggled into my bedroom and drank in the hour before I went to bed. Minutes before the intruder made his way up the stairs, I woke needing to go to the bathroom. I was then able to hide in there once it began. The lock was flimsy and there was no means of escape. If the killer had tried the door it would have yielded and I’d be dead as well. But for some reason, he didn’t.

We were the last family this man attacked but not the first. We were his fifth in two years. The media dubbed him the Nothing Man because the Gardaí, they said, had nothing on him. With the sole exception of a momentary glimpse in the beam of headlights on the side of the road one night, no one saw him coming or going. He wore a mask and sometimes shone a torch directly into his victims’ faces, so no survivor could provide a useful physical description. He used condoms and left no hair or fingerprints that anyone was ever able to collect. He took his weapons – a knife and then, later, a gun – with him when he went, only ever leaving behind the strands of braided blue rope that he used to restrain his victims. The rope never gave up any secrets. He spoke in a weird, raspy whisper that offered no clues as to his real voice. He confined his crimes to one county, Cork, Ireland’s southernmost and largest, but he moved around within it, striking places like Fermoy, a town nearly forty kilometres outside of Cork City, but also Blackrock, a suburb.

Nearly two decades later he remains at large and I miss my family like phantom limbs. Their absence in my life, the tragedy of their fates and the pain they must have suffered is a constant ringing in my ears, a taste in my mouth, an itch on my skin. It’s everywhere, always, and I can’t make it go away. Time hasn’t healed this wound but made it worse, turned the skin around the original cut necrotic. I understand much more about what I lost now, at thirty, than I did when I actually lost it at twelve. And the monster responsible is still out there, still free, still unidentified. Maybe he’s even spent all this time with his family. This possibility – this likelihood – fills me with a rage so intense that on the bad days, I can’t see through it. On the worst of them, I wish he’d murdered me too.

But you and me, we’ve just met at a Christmas party. Or a wedding. Or a book launch. And I don’t know you but I know that you wouldn’t know what to do if I said any of this out loud, now, in response to your question. So am I girl who …? I feign confusion. The girl who what? Just how many of those drinks have you had, anyway?

I’m good at this. I’ve had lots of practice. You will think you’re mistaken. The conversation will move on.

As soon as I can I will, too.

In the aftermath of the attack, my only surviving grandparent – Colette, my father’s mother – whisked me away to a place called Spanish Point on Ireland’s Atlantic coast. We arrived there in the middle of October, just as the last few seasonal stragglers were packing up, and moved into a tiny, whitewashed cottage that she said had been there since before the Famine. Its bright red door had been newly painted in advance of our arrival and every time I looked at it, all I could see was fresh blood dripping down pale bedroom walls.

We were there three weeks before I realised there must have been funerals.

The cottage was squeezed on to a narrow slip of land between the coast road and the yawning expanse of the seemingly endless sea, churning and wild, the winds angry to meet their first obstacle for thousands of miles. Our position felt precarious. Lying in bed at night, I’d listen to the roar of the waves and worry that the next one would rise up, crash down on to the cottage and carry away what was left of us with the force of its retreat.

It didn’t help that Spanish Point was so called because two ships of the Spanish Armada were wrecked against the headland there in 1588. According to local folklore, the sailors that didn’t drown were executed and buried in a mass grave in a spot called Tuama na Spainneach, the Spanish Tomb. Sometimes, in the winter months, when night arrived early, I stood on the beach as it darkened and imagined the ghosts of these men emerging from the sea. They always looked like a cross between Egyptian mummies and Hollywood pirates, and they were always walking directly towards me.

Our life in Spanish Point was painfully simple. We had no TV and no computer, and I don’t remember there ever being newspapers in the house. My grandmother, who I called Nannie, listened to the radio for a couple of hours in the morning but only ever stations that played traditional Irish music and never anything with news bulletins in between. We had a landline, which occasionally rang, but whenever it did I’d be shooed into another room or, weather permitting, sent outside while Nannie spoke to whoever was on the other end in hushed tones. The phone rang often in those first few weeks and months but afterwards, almost never. Eventually calls became so rare that the sudden shrill of the ringer would make us both jump and turn to one another, panicked, as if a fire alarm had just gone off and we hadn’t known there was a fire or even an alarm.

That first year almost every day was the same, our tasks expanding to fill however many hours we had like an emotional sealant, preventing the grief from bubbling up to the surface and breaking through. Each meal had a preparation, consumption and clean-up phase. Even a simple breakfast of toast and eggs could be stretched to an hour if we put our minds to it. Mid-morning we did what Nannie called the jobs, tasks like housekeeping and laundry. After lunch, we’d take a long walk down the beach and back, returning with an appetite for dinner. In the evenings, Nannie would light a fire and we’d sit in silence, reading our books, until the flames were reduced to embers. Then we would double-check the doors were locked, together, and go to bed.

It was only then, when I was under the covers, alone in my room in the dark, that I could finally give in. Let it in. The sadness, the grief, the confusion. I would yield and it would rush in and engulf me, a mile-high drowning wave. I knew no matter what happened during the day, whatever the effectiveness of Nannie’s distractions, this was what awaited me at the end of it. I cried myself to sleep every single night and dreamed of decomposing corpses writhing around in muddy graves. Anna’s, mostly. Trying to get out. Trying to get back to me.

We never, ever talked about what had happened. Nannie didn’t even say their names. But sometimes I heard her whimpering softly in her sleep and once, I walked in on her looking through one of my mother’s boxes of old photos, her lined cheeks wet with tears. I had so many questions about what had happened, and why it had, to us, but I didn’t dare ask them. I didn’t want to upset Nannie. I presumed that her and I being holed up in that cottage meant that the man who had murdered the rest of my family was still out there somewhere and that, by now, he knew that he’d missed one of us. Sometimes, in the twilight moments between sleep and wakefulness, I’d see him standing at the end of my bed. He looked like a killer from a horror movie: crazed, blood-splattered, wild. Sometimes the knife was in me before I’d wake up and realise it wasn’t real.

Once a week we’d go into the nearest town to exchange our library books and do our food shopping (or to get the messages, as Nannie called it – and as I did too until I realised, at college, that not everyone did). She wouldn’t let me out of her sight on these excursions and told me that, if anyone ever asked, I was to say my first name in full, Evelyn instead of Eve. Afterwards, when I started secondary school one year late, the forms had Nannie’s maiden name on them and I had been issued a further instruction. I was to say my parents had died in a car crash and that I was an only child, but only if I was asked. Never volunteer information, Nannie said. That was the golden rule and one I still follow now.

I didn’t question this. I just wanted to be normal, to fit in with the other girls in my year. I assumed that how I felt – like my insides were one big, raw, open wound and that my body was just a thin shell built to hide this – was a permanent state that would only be made worse by acknowledging it. I got really good at pretending that I was fine, that everything was, but it was a delicate surface tension that threatened to break at any time.

I pretended my way all through school, through my Leaving Cert exams and through four years of college at NUI Galway, where I chose to study a business course purely because it was a known quantity. I loved reading and writing and, the night I applied, sat for a long time with the cursor blinking over options with ‘Arts’ and ‘Literature’ and ‘Creative Writing’ in their title. But I couldn’t chance being trapped in a seminar room discussing things like trauma, or grief, or violence, especially not while strangers stared at my face. I’d be undone. Databases and mathematics seemed safer and they proved to be.

I didn’t dream of reanimated corpses or knife-wielding killers any more, but I had started tormenting myself by searching crowds for my sister’s face, looking for her proxy, for someone who matched what I thought she might look like now – which was what I looked like when I was sixteen, because that was my only data point. I never found any candidates.

‘Is it any good?’

Jim snapped the book shut, releasing a sound that seemed as loud as a thunderclap.

Steve O’Reilly, the store manager, was standing beside him. Leaning against the shelves with his arms folded, wearing his trademark expression of bemused superiority.

The inside of Jim’s head was an echo chamber of screams. I was twelve years old … A man broke into our home ... murdered my mother, father and younger sister …The lock was flimsy … But for some reason, he didn’t. He mentally beat them back until he found the words, ‘Not really my thing,’ and returned the book to the shelf, taking the opportunity to pull in a deep breath and moisten his lips.

His fingers had left misty smudges on the book’s glossy black cover.

‘Oh yeah?’ Steve raised his eyebrows. ‘Could’ve fooled me, Jim. You looked like you were well into it.’

Steve was twenty-six and wore shiny suits and came to work every day with globules of gel hardening in his (receding) hairline, yet somehow had the idea that he was a somebody and Jim was a nobody. The greatest challenge of working for him was resisting the urge to correct him about that.

Jim turned to face Steve dead-on. He mirrored his stance, folding his arms and leaning lightly against the shelves, a simple trick that always seemed to make other people uneasy. He settled his face into a perfectly neutral expression and looked Steve right in the eye.

‘Did you need something, Steve?’

The younger man shifted his weight.

‘Yeah. I need you to remember that you’re here to work. This isn’t a library.’ He reached out and took down the same copy of The Nothing Man that Jim had just returned to the shelf. ‘The Nothing Man? What were you doing, Jim? Reliving your glory days? Oh wait, no – you were sitting at a desk somewhere, weren’t you? They didn’t let you chase after the actual criminals.’

Steve cracked open the book right in the middle, where the pages were different: bright white, thick and glossy, and displaying photographs.

On the page to Steve’s left was an image of a large detached house and a family of young children posing by a Christmas tree.

On the opposite one, a pencil sketch.

The pencil sketch.

Steve tapped the page. ‘Yeah, yeah. I’ve heard of this.’

Jim was looking at the sketch upside down but he didn’t need to look at it at all to recall it perfectly. It was of a man with small, hooded eyes set deep into a round, fleshy face. Wearing what looked like a thick knit hat pulled low enough to cover his eyebrows. The angle was slightly off, the head turned a few degrees to the left, as if the man had just heard the artist call his name and was still in the process of turning to respond to it.

In the book, the sketch took up two-thirds of the page above a small paragraph. Presumably the text said something about it being based on the testimony of a witness who had happened to drive past the house owned by the O’Sullivan family of Bally’s Lane, near Carrigaline, Co. Cork, in the early hours of 14 January 2000, and caught this man walking along the side of the road with her headlights. Walking furtively, she’d said. It was the only glimpse of the killer they called the Nothing Man that anyone had ever got.

Jim had made sure of it.

That night, while he waited in the darkness, he thought he’d have some warning if a car approached, that he’d hear the rumble of the engine long before its lights lit up the road. But the car driven by Claire Bardin, an Irishwoman living in France but home for Christmas, seemed to come out of nowhere. She’d surprised him, coming suddenly around a bend, and, unthinking, he’d looked directly into the light. Recalling it now, Jim thought he felt a cold breeze, and for a split second he was back in the dark on the side of the road, tense and determined, his body fizzing with adrenalin.

It would have been impressively accurate even if Bardin had driven straight to the nearest Garda station to meet with a sketch artist that very night. But she’d done it six months later when, on a trip to Cork for her sister’s wedding, she happened to read a news report about the attack and realised that the date and place matched her odd sighting, which made its accuracy remarkable. The morning after Jim first saw it in a paper, he’d started swimming lengths of the local pool every day until the flesh on his face began to tighten and cling, revealing a harsher jawline and hollows beneath his cheekbones.

But the eyes and ears. They didn’t change with weight or age – the eyes especially. Even if you opted for surgery you couldn’t change where they sat in the bone structure of the face, the distances between them and your other features.

And Claire Bardin had got them exactly right.

Back in the present, Steve was frowning at the sketch.

‘Get back to work, Jim.’ He snapped the book shut and tucked it under his arm. ‘I’m off on my break. Don’t let me see you still slacking when I get back.’

Once he knew the book existed, Jim could think of nothing else. It was a ring of fire around him, drawing nearer with each passing moment, threatening to torch every layer of him one by one. His clothes. His skin. His life. If it reached him it would leave nothing but ash and all his secrets, totally exposed.

He had to put it out. Now.

But what was it, really? What was this book? Why had she written it? Why now? Nothing had changed. No one had come for him. If it really was about her search for him then he already knew the ending: spoiler alert, she hadn’t found him.

But that wasn’t enough. Jim needed to know what Eve Black had filled all those pages with, what she’d been doing since he saw her eighteen years ago standing at the top of the stairs, what she was telling the world about that night.

When one of the checkout girls asked Jim if he was feeling okay – he looked flushed and sweaty, she said, was he coming down with something? – he saw an opportunity. He radioed Steve to tell him he was going home sick, then turned the radio off before Steve could come squawking back. He punched his time-card and hurried to his car in the shopping centre’s staff car park.

But Jim didn’t drive home. He drove straight into the city.

There was a branch of Waterstones on Patrick Street. He’d only been inside once or twice, a long time ago, but he remembered that it was big and that it ran all the way back to Paul Street on its other side.

Jim didn’t think he was in any danger but still, there was no need to draw attention. He wasn’t going to buy the book from the store where he worked, and neither was he going to get it from some tiny shop where the clerk would likely remember every customer and what they purchased. Buying it online would leave a digital trail and take too long.

Jim needed a copy now.

He parked in the multi-storey on Paul Street and walked to the bookshop’s rear entrance. He had put his coat on, hiding his uniform. As the doors swung shut behind him, the buzz from outside died and he was cocooned in the hush of the bookshop.

There were three, four other customers that he could see, plus a guy in a T-shirt in the corner stacking shelves. Way too quiet altogether. There wasn’t even a radio playing.

Jim slowly but purposefully made his way to the front of the shop at the other end. He made sure to look like a typical customer. Picking up the odd book here, there, admiring it, reading the back, putting it down again. Stopping to inspect special offers. Having a cursory flip through the books in a bargain box marked LAST CHANCE TO BUY.

He found The Nothing Man just inside the main doors.

It had its own table. There were stacks of it on there, each one several books high, arranged in a semicircle. One copy was standing upright in the middle, resting on a little Perspex mount. A handwritten card promised, The story of Cork’s most famous crime, told by a survivor.

Jim picked one up and placed a palm flat on the cover, as if he could feel what the pages inside held for him, for his future.

Was it all in here, every bad thing he had done, all the things he had packed away since? The Nothing Man was a threat, yes, but the idea of reading it, of reliving his glory days …

It also brought the giddy promise of a treat.

‘Just came in today, that one did.’ A smiling man was now on the other side of the table, three feet in front of Jim. Mid-forties, dressed casually, wearing a name-tag that identified him as Kevin. ‘Great read, by the way. If you can stomach it. Crazy to think it all happened right here.’

‘You’ve read it?’ Jim asked.

‘A couple of months ago. We get sent advance copies.’

‘And did she? Find him?’

‘No. Well, yes and no. You see, it’s hard to say ...’

No, it wasn’t. Because here Jim was, still free, still unidentified. He considered asking Kevin to explain himself, but he’d already had more of a conversation than was probably wise. Two teenage girls in school uniform came pushing through the doors, laughing and talking loudly, distracting Kevin, and Jim took the opportunity to snatch up a copy of the book and walk away.

The cash desk was in the middle of the shop. En route, Jim picked up another book the same size as The Nothing Man. Its cover was mostly baby-blue sky above a row of multicoloured beach-huts. He also lifted the first greeting card he saw that said HAPPY BIRTHDAY from the selection by the register.

The cashier was female. A young, artsy, college-student type who considered each title with great interest as she scanned its barcode.

‘Bit of a random selection,’ she said wryly.

Mind your own business, Jim wanted to roar.

He said, ‘Well, I’m not sure what she likes. My wife. It’s her birthday.’

‘And so you’re …’ The cashier looked at the two contrasting covers in front of her. ‘Hedging your bets?’

‘Something like that.’

‘If you like, I can help you pick—’

‘I’ll just stick with these, thanks.’

He had planned to leave the store the way he’d come in, but Kevin was down that end of the shop now, straightening shelves, so he turned on his heel and made for the main doors instead.

As he pushed through them, he saw that the entire front window was filled with copies of The Nothing Man.

Behind them, pinned to a red felt board, was a collage of old newspaper clippings.

Horror attack in Blackrock.

Special Garda Operation To Chase ‘Nothing Man’.

Family of 4 Dead in Murder Spree in Passage West.

The last one was factually incorrect, a misprint the morning after when the exact details from inside the house on Bally’s Lane were still as messy as the scene itself.

Only three people had died in that house.

That, now, was the problem.

Back in the car park, he sat in his car and locked the doors. He had purposefully parked in a far corner, away from elevators and the pay machines and so, passing foot traffic. He took the second book, the one with the beach-huts on the cover, out of the bag and slipped off its dust jacket. Then he did the same with his copy of The Nothing Man and swapped the two over, so now each book was wearing the ‘wrong’ cover, disguising its true content.

Just in case.

Jim opened his own copy of The Nothing Man and flicked through the opening pages until he found the spot where Steve had interrupted him.

Then he shifted in his seat, getting comfortable, and read on.

Every weekend, holiday and summer break I returned to Spanish Point and fell back into life with Nannie the way you fall into your own bed at the end of a long day. I took her greying skin, her shrinking size, the tremors that had crept into her voice, and I put them away with everything else I was determined not to think about.

Nannie died in her sleep on the Feast of the Assumption in 2010, aged eighty-four. I remember finding her in the morning, the temperature of the skin on her forearm telling me that it was already too late to call for help. Then nothing except blurry, fragmented images for weeks after that.

I had never really grieved for my parents and my sister, not actively, not in the way that helps a person process their pain and find a way to move forward, around it, alongside it. Now I was grieving for them all. It was as if the tectonic plates beneath my life had shifted, yawning apart, creating a deep and treacherous chasm into which every steady thing suddenly slid. I was the only thing still standing now, the only one of us left, and my feet were slipping. The problem was that, by then, I’d got so good at pretending, no one could tell.

I finished my degree, graduating with a first. A college friend was now a boyfriend, even though I could never quite trace the threads of our backstory and he knew practically nothing of mine. I sat through what felt like endless meetings in over-lit offices with dusty vertical blinds while document after document was slid across a table to me so I could sign my name by the colourful little stickers that seemed far too jaunty for the task at hand: taking ownership of things that didn’t belong to me because now I was the only one left.

I pushed everything down, down, down, until it was safely locked away beneath the numbness.

I was twenty-one years old.

When college ended, I was set adrift. Studying was a series of small tasks that, once completed, were instantly replaced with another, like a game of whack-a-mole. Get to class. Get that project completed. Study for that exam. All I’d had to do during those four years was keep moving forward, keep putting one foot in front of the other, start on the next thing. Now there was nothing to do except think of things to do, and I found that I couldn’t do that at all. Over the course of six dark months I unravelled, melting into a dull puddle of the person I had been – or had pretended to be. I lost the boyfriend, my few friends and too much weight, in that order. I was a compass needle that couldn’t find true north. The truth was I wasn’t trying to find it, not really. It was so much easier to stop looking, to let go, to sink. And besides, where on this earth were you supposed to point towards when you had no family left?

The quick sale of Nannie’s home in Cork meant that I was under no immediate pressure financially, so while my classmates took up exciting jobs abroad and postgraduate places, I rented a crappy bedsit off Mountjoy Square and bedded down. I made my life so small that not even my neighbours knew me. At night I lay awake and during the day I sleepwalked. I don’t even know how I passed the hours, only that the time passed and afterwards I had nothing at all to show for it, not even memories.

After months of this, when I could no longer deny that something greater than my own grief was pulling the circuits apart in my brain, I managed to drag myself to a doctor who pushed me on to a therapist, but I couldn’t bring myself to tell her the real reason I was there, who I really was and what I’d suffered. Each week I said just enough to keep her writing me prescriptions. I wasn’t even sure the pills were doing anything for me but at the same time I was absolutely terrified that they were. I didn’t want to find out if what felt like rock bottom was merely halfway down. So I kept going to therapy, kept taking the pills, waiting to feel something different, differently.

And then, finally, things began to change.

I started to sleep at night, bringing my days back into focus. That made me feel restless and jittery in the flat during the day, but there was nothing I had to do, no one to see and nowhere to go. So I started to walk. For miles and miles, on paths that hugged the edges of Dublin Bay. Usually heading off around eight o’clock in the morning, pushing against the workers striding into the city until I was out of it and free of them, and feeling free as the rising sun broke into shards of light on the water feet away from me. My go-to route was north out of town and along the water as far as Clontarf, but sometimes I pushed on to Howth Head, and once I walked south across the river and kept going until I found myself in Dun Laoghaire hours later, where I collapsed into a seat on the 46A and slept all the way back.

But it wasn’t the same on dull days and I had no interest in doing it on the wet ones. I started searching for an alternative rainy-day activity, something that would get me out of the flat but into another dry, warm place. I choose the library, the largest one I could find, right in the heart of the city centre. There was a steady stream of people into and out of it so I could be anonymous, moving among them unnoticed if not unseen. I started hiding in corners, eyes skimming the same page for the umpteenth time as rain drummed against the windows and our collective breath turned them misty and opaque. Eventually I began to forget myself, falling into whatever book I’d selected as a prop. I found I had an attention span again. Soon after that I was borrowing, bringing books home to read into the evening or even bring with me on my walks. Then came cooking: simple, wholesome meals from scratch. Taking care of the rooms in which I lived. Taking care of myself. I didn’t recognise it as such at the time, but I was doing for myself what Nannie had once done for me: keeping a simple, quiet life that would help to heal me. I had always assumed we were merely hiding.

I can’t say exactly when the last wisps of my fog disappeared, but they did. When they did, I bought a notebook and a pack of sharp pencils, because I knew what it was that I was going to do next: take a chance.

If you think you’ve read some of these words before, you may have. If you have, you already know what I did next.

In September 2014, I began a Masters in Creative Writing at St John’s College in Dublin. I choose St John’s partly because they were willing to choose me, but also because the campus was already associated with horrific crimes. Several years before, five female first-years had been snatched from the paths that ran along the Grand Canal, their route back to their halls of residence after a night out in the city’s pubs and clubs. Each one was left unconscious beneath the black waters to drown, and drown they did. The Nothing Man may have been a headline for a time, but the Canal Killer was an industry, spawning documentaries and blogs and – the latest thing – podcasts, even then, years after the fact. (Unbeknownst to anyone but the Canal Killer himself, the story would soon be continuing. There were three new murders connected to St John’s and one attempted one while I was writing this book.) I figured this was the only university in Ireland that already had its own monster and he was even more notorious than mine. I might go unnoticed. I might get not to be the Girl Who in the Place Where.

I wanted to write. Had always wanted to. What or how or for whom, I didn’t know, but since I had dragged myself out from under the darkness, I had been thinking about it more and more and now, finally, I’d made a decision. I would learn how and then I would do it. I had notions of writing a novel, something dark and twisty into which I could – anonymously – pour all of my pain. This path was fraught with danger but I was stronger now and once again ready to pretend. That’s what fiction was, wasn’t it? Pretending?

Not according to our course director, the renowned novelist Jonathan Eglin, whose debut novel The Essentialists was longlisted for the Booker Prize. He told us this in our very first class. He said that fiction only really worked if it was built like a lattice through which you were repeatedly offered glimpses of absolute truth. That was our aim, regardless of what form our writing took. He then proceeded, over the course of those first few weeks and months, to systematically sandpaper away all of our armour, our masks, our carefully constructed personhoods, until we were left naked and bleeding directly on to the page.

I resisted as long as I could. I was sure, I was absolutely certain, that if I as much as put the words when I was twelve years old a man broke into our home and murdered my mother, father and younger sister, Anna, seven years old then and for ever on to a virtual page or dared write them in ink on a real one, what little ground I’d secured to stand on would collapse beneath my feet. There’d be no coming back from the depths of that abyss. So I wrote short stories about happy families who loved each other. The act of creating them comforted me. Whenever I wrote, I got to go back and see them, and find out what had happened to them since. The time I spent at my laptop were my visiting hours.

Then came the day of the forgotten deadline. It dawned on me one afternoon like a bullet of stone-cold dread to the chest: I had to submit two thousand new words first thing the following morning, for a grade, and I had completely forgotten about it until that moment. I holed up in the library late into the night, but found myself paralysed by the blinking cursor. No matter what I tried, the words just wouldn’t come. I walked home on dark, wet streets and sat in my bedroom, staring helplessly at the still-blank white space onscreen.

The clock ticked past midnight, bringing a new date to the display on my computer: 21 March. Anna’s birthday. That one would’ve been her twenty-first.

The words began to bubble up inside me, unbidden. I would write about her, I decided, and change the names once I was done. It wasn’t a good idea but, in that moment, all I was really concerned about was getting myself out of this jam, away from the blank page and its awful emptiness. I started typing. When I was twelve years old a man broke into our home and murdered my mother, father and younger sister, Anna, seven years old then and for ever…

Eglin wasn’t fooled. The piece had a quality to it, a scalpel-grade sharpness, that none of my previous work had even hinted at the promise of. Half an hour after I emailed him the piece in the grey light of the early hours, Eglin emailed back to ask me to come to his office first thing. I steeled myself as I walked down his corridor of the Arts building, ready to deny all, but he didn’t even bother asking me if it was true. He already knew it was.

Instead, he urged me to publish it.

I remember not knowing what to say, not knowing where to begin with why that could never happen. And then him saying, very softly, ‘But, Eve, you might catch him with it.’

And that, then, changed everything.

It felt like flinging myself off a cliff. The night before I knew the piece was due to go live, I dreamed of Anna, crawling out of the sea like the Spanish sailors had when I was a child. She looked like a banshee. She came clawing at me with rotting fingers, her blonde hair wild and tangled with seaweed, screaming at me for failing to protect myself. But I was beginning to realise that protecting myself was also protecting him. I couldn’t get them back. But I could, maybe, make him pay for their taking.

My piece went live on the Irish Times website at 4:00 a.m. on the last day of May 2015 and appeared in their print edition later that morning. By close of business, I had officially gone viral. It started on social media, where a few influential accounts shared a link, and then the people following them started to share it. It was picked up by a broadsheet in the UK, then a monthly magazine in the US. Everyone, it seemed, had always wondered what had happened to that girl who’d survived the Nothing Man’s worst and final attack. Now they knew some, they wanted more and more.

Intrepid reporters found my contact details via the St John’s College student portal and invitations to appear on radio and TV shows started to stream in. I couldn’t possibly talk about what had happened in real time – I wasn’t physically able for that yet – but I wanted to do something. Eglin put me in touch with his editor at Iveagh Press (pronounced like ivy), who encouraged me to expand the article into a book. She said if I did, she would publish it. This is the book you hold in your hands now.

Just a few weeks earlier, agreeing to write a book about what had happened to my family would’ve been utterly unthinkable. But when ‘The Girl Who’ went viral, something else important had happened to me too.

Within hours, articles about my article began to pop up online. Classmates of mine kept sending me links to them, excited that one of us was making such a splash with our written words, seemingly oblivious to the pain behind my story. At first I ignored them. I’d never read anything about the Nothing Man case. I had steadfastly avoided doing so. In the years since that night, I’d never learned anything more than the broad strokes of what he had done to my family, and they were bad enough. I didn’t want the blurry shapes to come into focus. I knew I’d never be able to unsee them again.

But eventually, curiosity got the better of me. I started clicking on the links, scanning rather than reading the articles they led to, keeping the text moving ever upwards on the screen.

In the fourth or fifth one I looked at, I was stopped cold by a phrase.

rope and knife beneath one of her sofa cushions

I went back to read the sentence from the beginning. Gardaí had already been to the apartment complex two weeks before, when another tenant, a single woman living alone, discovered a rope and a knife beneath one of her sofa cushions. She hoovered there on the same day every week and was certain the items had not been there the week before, and to her knowledge, no one else had been in the apartment since. She immediately reported the find to her local station. Gardaí would come to believe that the Nothing Man had planted them there on a preparatory visit, ready to use on his return.

My pulse pounded in my ears. Because I, too, had once found a rope and a knife beneath a couch cushion.

But I’d never told anyone about it.

It was shortly before the attack, maybe mere days. I was watching Anna for half an hour while our mother popped to the shops, and she’d convinced me to play a game that, for some reason lost to me now, necessitated that every cushion from every chair in the living room be tossed on to the floor in a pile. When I lifted the last remaining cushion from the couch, the action revealed two items lying amid the biscuit crumbs, lost hair-ties and sticky copper coins: a rope and a knife. The rope was braided and blue, and was still looped neatly inside the glossy band that served as its packaging. The knife was about the length of a hardback book, with a thick yellow plastic handle that reminded me of Fisher Price toys. The blade had little jags along the edge and it looked very, very clean, if not brand new. Shiny.

I didn’t wonder what they were doing there. My mother had a habit of storing things under couch cushions – the post mostly, the bills she wanted to hide from my father, but also the odd magazine or knitting pattern – so although I thought these were strange items to find there, it didn’t strike me as particularly odd. I knew enough to know the knife was a potential danger, so I put the cushion back and told Anna the game was over.

Weeks later, when I saw that same blue rope tied around my father’s wrists and ankles as he lay broken and contorted at the bottom of our stairs, the connection my brain made was that man used my dad’s rope. It never occurred to me that the Nothing Man had been to our house in advance of the attack, that he’d put the items under the cushion. That doing so was part of his preparation, that he was going to come back and use them. After the attack I had had one Garda interview, during which I cried endlessly and choked out one-word answers. The rope had never come up. I was numb and in shock and twelve years old; it never crossed my mind to connect the two events. At some point I’d forgotten about it altogether.

The sudden realisation that I may have been able to stop it, to prevent it – the idea that if I had just told someone about the rope and the knife I might have saved my family – was too much to bear. It was a pressure that pushed down on me, crushing my lungs, smashing my heart into sharp pieces all over again. It is still the most intense pain I have ever experienced. Even worse, somehow, than the original loss, because now I saw that it didn’t have to happen.

But mixed in with this was another, more welcome revelation: after all this time, the Nothing Man investigation might have a new lead.

The night he came and killed my family wasn’t the first time he’d been in our house. He’d been there before, perhaps more than once. Could someone have seen him on those occasions? I could describe the knife. What if it was an especially distinctive one, only available to buy from certain places? Would that help find him? Could it, now, even though nearly twenty years had passed?

What else did I know? Could I have other useful information, hidden in plain sight in my memories? Could the other survivors, the other victims? And what about things like DNA, forensic science? They were better now than they’d been then, and were getting better all the time. What if we went back and looked for the Nothing Man again, now?

What if, this time, we found him?

What if I did?

So ask me again. Am I the girl who …? Because this time – these days – I’ll tell you the truth: no, but I was.

I was the girl who survived the Nothing Man.

Now I am the woman who is going to catch him.