1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

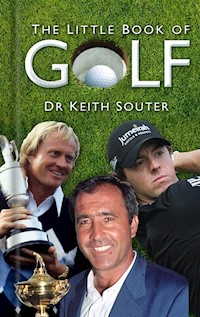

Golf is one of the most popular games in the world. That is a strange thing to say, since almost all serious golfers actually have a love-hate relationship with it. A good round can bring great joy and satisfaction, while a bad round can end in depression, a binge at the bar, arguments with one's partner and the need for prompt evasive action by the family cat. Although this book is written in a light-hearted manner, it contains a wealth of information about every aspect of the game. Learn about its long and speckled history and some of the quirky characters who have graced the links. It also has some advice on putting and chipping, two parts of the game which cause the occasional golfer frustration, heartache and sore knees after repeated attempts to break the clubs. Failing that you will find a selection of fascinating anecdotes about the game's greats and plenty of intriguing trivia.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

For Andrew, my son and golfing partner. This is for you with fond memories of the ups, downs and vagaries of this game that we have shared over the years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing this book has been a great delight, if for no other reason than it has given me a quite legitimate reason to leave my study, pick up my bag of clubs and head off to the links on a regular basis. Ah, the bliss of research! Yet there are several people that I must thank for their parts in bringing this modest little volume to public view. Firstly, I thank Isabel Atherton, my fantastic agent who first suggested that I should stop talking about golf and organise my thoughts into a book. Her advice has been greatly valued, as always.

Michelle Tilling, the commissioning editor at The History Press, kindly read through the book proposal and took it on board. I thank her for giving me a genuine reason to play more golf and to read more golf books and watch more golf movies.

Richard Leatherdale, my editor, helped to get the book into proper reading condition, for which I am grateful. If he ever gives up editing, I am sure he would make an excellent greenkeeper.

Fiona McDonald performed a sterling job in transforming my illustration ideas into actual line drawings. It has been a joy to work with her on this, our second book for The History Press.

Finally, thanks to my wife Rachel for listening to my endless anecdotes and reports of my adventures on the links while researching and writing this book – at least I think she was listening!

INTRODUCTION

Golf is one of the most popular games in the world. That is a strange thing to say, since almost all serious golfers actually have a love-hate relationship with it. A good round can bring great joy and satisfaction, while a bad round can end in depression, a binge in the bar, arguments with one’s partner and the need for prompt evasive action by the family cat.

Golf is unique in that it can be played by people from any age from 3 to 103. It has a unique handicapping system which permits the most abject hacker to play with a top professional in such an even way that they can have a real needle of a match. No other sport offers this.

The fact that people of all ages, all builds and all abilities can play this game may suggest to the untutored that it does not take up much energy, that it is a mere pastime rather than a sport. Say that to a golfer and you risk a verbal tongue-lashing at the very least – people become addicted to golf and as a breed of addict they are incredibly loyal to the game that gives them their fix.

Golf is an equipment sport in which a stationary ball is struck with a variety of clubs. It is played on a large area of land called a golf course, which contains nine or eighteen neatly tended undulating lawns or greens, each of which has a small hole in it measuring exactly 4¼ inches in diameter. The aim is to play each hole in as few shots as possible, and the whole course as near as one can to par or less. Only a minority of players are capable of this. Although this book is written in a light-hearted manner it contains a wealth of information about every aspect of the game of golf. Learn about its long and speckled history and about the early clubs, such as the ‘mashie’, ‘spoon’, ‘clique’ and ‘niblick’ and see how they developed into the metal-headed ‘woods’ and ‘hybrids’ of today. Rejoice in the great names of yesteryear, today and tomorrow. Enjoy finding out about some of the strange things that have happened on links around the world. Read about its strange terminology, its quirks, and the maladies that golfers develop. Find out about strange aberrations like urban golf and read about the different tournaments and the majors of golf, which are the measure by which professionals are evaluated. See also how the game has drifted into literature and films, like a controlled fade that sweeps over the out of bounds and curves neatly back onto the fairway.

For the occasional golfer who finds putting and chipping a total mystery, there are even chapters that may help. Indeed, if the very psychology of the game interests you, there is a chapter on this.

Never was there a Little Book of anything quite so full of it as this one.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 The Origins of Golf

2 Golf Times

3 Balls

4 Clubs

5 The Courses

6 The Championships

7 The Golfing Greats

8 The Ryder Cup

9 The Other Major Team Matches

10 Urban Golf

11 Golf in Books and Film

12 Putting

13 Chipping

14 Golf Psychology

15 Golfing Maladies

16 Scoring

17 So What do you Want to Play?

18 Etiquette

Glossary

About the Author

Copyright

1

THEORIGINSOFGOLF

‘Golf is an ineffectual attempt to put an elusive ball into an obscure hole with implements ill-adapted to the purpose.’

Woodrow Wilson (1856–1922),

28th President of the USA

‘IV!’

Ludicrous Golfus (AD 72–101)

(Latin trans: Four!)

[Author’s note: Often mistranslated nowadays as ‘Fore’]

Where did it all start? Golf, I mean.

It really is a curious game, the origins of which seem to be lost in the distant mists of time. Most people would say that it started somewhere on the east coast of Scotland, possibly in St Andrews, that fair grey town in Fife where I was born. This picturesque old university town is renowned around the world as the home of golf. With the impressive Royal and Ancient Golf Club overlooking the Old Course, and with its long tradition of great champions, nail-biting matches, club-makers on every street corner and the most knowledgeable caddies touting for trade in the many hostelries around the town – it just oozes golf.

Such is the esteem in which the venerable old St Andrews golf club is held that it is known worldwide. It is one of the most exclusive golf clubs in the world; indeed, more than that, up until 2004 it was one of the governing bodies in golf. In that year the responsibility was taken over by a group of companies which are collectively now known as the R&A – this is the ruling body for golf all over the world except for the USA and Mexico. That gives it quite a lot of kudos and most golfers will doff their caps and accept St Andrews as the home of golf.

Home it may be, yet that does not mean that it is the place where someone first took a bash at a pebble with a stick and launched it towards a hole in the ground some distance off. There are actually a myriad of places dotted about Scotland that could claim to have had the first golf course. Musselburgh, a little town on the Firth of Forth, just 6 miles away from Edinburgh, was established by the Romans and is authenticated by no less an authority than the Guinness Book of Records as being the home of the oldest golf course in the world.

There is documentary evidence that golf was being played there back in the seventeenth century. An extract from the account book of Sir John Foulis of Ravelston (1638–1707) – a keen sportsman, lawyer and social historian –records that golf was played as early as 2 March 1632, although apparently Mary, Queen of Scots played there in 1567.

We will keep coming back to this place throughout this book.

THE FIRST KING OF GOLF

King James IV is recorded as being the first Scottish king to have seriously taken up golf when he played at Perth in 1502. That is not the pale Australian imitation, of course, but the real Perth that you come to if you head north from St Andrews. Now King James IV (1473–1513) was an interesting monarch. He came to the throne at the age of 15 and proved himself to be one of the most remarkable of men by anyone’s standards. He brought peace to Scotland by beating the heck out of any dissenting nobles on the outer reaches of his kingdom and then he set about educating them. He enforced all landowning families to send their sons to school and then on to one of the three ancient universities of St Andrews, Glasgow or Aberdeen. He was a scholarly monarch and was in fact a dentist.

That’s right, that’s what I said, he was a dentist. His gracious majesty himself, a King of Scotland actually practised dentistry and surgery. So enamoured was he with the healing arts that he granted a royal seal to the barber-surgeons of Edinburgh in 1506.This Seal of Cause (or charter of principles) stated:

that no manner of person occupy or practise any points of our said craft of surgery . . . unless he be worthy and expert in all points belonging to the said craft, diligently and expertly examined and admitted by the Maisters of the said craft and that he know Anatomy and the nature and complexion of every member of the human body . . . for every man ocht to know the nature and substance of everything that he works or else he is negligent.

In fact, this seal could almost be a blueprint for the practice of any skill, whether that be dentistry, surgery or golf.

King James IV’s grandfather, King James II, who was known behind his back as ‘Fiery Face’, had actually banned the playing of both golf and football on the Leith Links back in 1457, because it interfered with the practice of archery, which was so important for the defence of the realm. In banning the game, old Fiery Face had said that, ‘Golfe be utterly crit doune, and noche usit,’ meaning that the game should be cut down and never used or played. You can see that the old boy was no fun-loving sport.

But happily, in 1502 King James IV, the finest of the Stuart dynasty, removed the ban because he no longer saw a threat from England, having just signed a Treaty of Perpetual Peace with King Henry VII. Although he did not know it, it would be several years before Henry VII’s son, known to history as bluff King Henry VIII, would start stirring up trouble again.

Some historians believe that one of the main reasons James got rid of the ban was because he had grown tired of dentistry and fancied becoming a golf pro instead. It is doubtful if we will ever discover the truth. As it was, James set off from Scone Palace and bought his first set of golf clubs from a bow-maker in Perth. It is set out in the royal accounts for the year 1502, ‘Item: the xxi Sept – to the bowar of Sanct Johnestoun, for golf clubs, xiiii s’, which means that he paid 14s to the bow-maker for a set of good clubs; that would be the equivalent of about £350 in today’s money, which would be considered something of a bargain. It is hoped, however, that the bow-maker knew that a golf club is ideally made straight, rather than with the shape one associates with a bow.

A SORT OF NOBLE GOLFING CHAPPIE

The year 1457 is the first actual reference on record about the game being played in Scotland, although clearly it had been played regularly before that time. It is likely that old Fiery Face, King James II had been seething about both golf and football for a good few years before he decided to knock both games out of bounds. It may even be that the chap had played a bit himself, only to find that he was a right royal hacker, easily outplayed by those less regal than himself. Perhaps it was royal pique rather than national pride that caused him to blot his copy book as far as golfing history is concerned.

There are, of course, other types of evidence that historians are willing to look at apart from documentary evidence. One such interesting pieces of information is a stained-glass window in Gloucester Cathedral.

This rather beautiful piece of medieval glasswork is hailed by some golfing historians as showing that golf was actually played in England in the 1340s and the figure depicted has been described as a ‘sort of noble golfing chappie driving off.’

This, of course, is complete drivel as an examination by any real golfer (which I hope the reader either is, or aspires to be) will tell you. For one thing the ball is huge – that is no golf ball, I can tell you that. Also, the player is right-handed and has raised his club or stick to his right in readiness to strike the ball that is clearly not stationary. Indeed, the ball is advancing towards him, not departing from a tee, otherwise the depiction would be of the ‘chappie’ with the club on the other side of his body, or as we say in golf in ‘follow through’. And if you are not already convinced, just look at his left foot, clearly that is not the position of a man who has taken up a golf stance, but of someone who has just taken a step in order to thwack a ball hard. No, that is a picture of someone playing a game like hockey, not golf.

A consideration of the history of the ‘first golfer’ window tells us more. It is situated in the east wing of the cathedral and was commissioned by Sir Thomas Broadstone in 1349, to commemorate his fallen comrades at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, when King Edward III’s archers decimated the French army during the Hundred Years’ War. This little panel is incongruous even in this context, since it is patently not a battle scene. The suggestion of other historians (mainly French golfing aficionados wanting to claim the game, I suspect) is that it is a depiction of the game of chole, which we shall consider shortly.

DOES THE NAME GIVE US A CLUE?

Golf is a strange word; there is no getting away from it. It doesn’t sound like an English word at all. So could it be of Scottish origin?

In old Scots the game is called ‘gowff ’ which actually means ‘to strike hard’. That sounds perfectly plausible, but that is all. If that really is the origin, then how did it linguistically get changed to golf? In other words, why the ‘l’ did it change from that ‘w’ in the middle?

Howff is a similar word, which means shelter or meeting place. There are still lots of howffs in Scotland that have remained unchanged – should that not have changed as well? That would mean that we should find lots of shelters called ‘holf’, but we don’t, so I suspect that the Scots term gowff, meaning hard strike, thump or drive does not relate to an original term, but is a kind of slang term that was similar to the original word used for the game. This would be in keeping with the fact that there are lots of old Scottish documents that variously describe the game as ‘gowff’, ‘goff’, ‘gof’, ‘gouf’, ‘goif’ and ‘golve’.

So what are the other contenders? Let’s look at them.

Chole

We don’t know how old this game is (though it’s thought to have been played as long ago as the thirteenth century) but it is still played in southern Belgium. Played by two teams of three players, one team were referred to as the ‘chole players’ and the opponents were called the ‘decholeurs’. It was played cross-country with a wooden ball and clubs, the chole players having three successive shots to strike the ball as far as possible towards a distant target, which could be a rock, a tree or even the door of a house. Once they had their three shots a decholeur player would have one shot to knock the ball as far back as possible, or into an awkward position. Thus the game progressed three shots forward and one shot back for as many shots as was predetermined, or until a score was ratcheted up.

This was not unlike croquet played in the wilds and it has to be a good contender for the original game.

Jeu de mail

This was a more genteel game played on a lawn, not very dissimilar to croquet, which it probably preceded. It is uncertain whether it began in Italy or France, but it became popular in manors, towns and villages where small jeu de mail courts would be laid out. It was played with clubs, balls and hoops and existed right up until the French Revolution when all sorts of cuts in sports, sportsmen and even the odd aristocrat were made.

The name, although French, derived from he Latin malleus, meaning hammer or mallet.

Pall Mall

This was an anglicised version of jeu de mail, which became very fashionable in London in the mid-seventeenth century. It was played on a much larger course than the lawn game that it was derived from. Indeed, the original course was laid out at Pall Mall near St James’s Palace. It was later moved to The Mall.

Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary of 1661 that he went: ‘To St James’s Park where I saw the Duke of York playing at Pelemele, the first time I ever saw the sport.’

Colf or Kolf

The Dutch also have a great claim to being the first to have played a version of golf, and the name that they used, colf or kolf, certainly sounds convincing.

There is a reference to it having been played as long ago as 1297 in the town of Loenen aan de Vecht, in the province of Utrecht, where a course of four targets was designed and a game played to commemorate the relieving of Kronenburg Castle in 1296. Rather like the Belgian Chole, the targets were not holes, but a door, a windmill, a courthouse and a kitchen.

Curious choices of targets, you may think, but then, everything about golf is curious.

SCOTTISH LINKS

So we come back to Scotland. It does not take a quantum leap to imagine traders from Holland travelling across to the east coast of Scotland and bringing with them the idea of colf or even of chole. Similarities in the names are tantalising, but even those similarities do not entirely help us, because the origin of those words in the respective languages is not precisely determined. They may have meant clubs or something to do with clubs, rather like the Scots’ gowff.

Yet at some point links were set out. We take the word now to simply mean a golf course set out at the seaside and certainly this terrain in Scotland lent itself to a long-distance version of colf, chole or jeu de mail. The rules would almost certainly have been adapted and, since the great outdoors of the Scottish seaside landscape probably had a dearth of windmills, courthouses and the like, some Scottish genius must have thought of the idea of making a hole a target on some sheep-grazed area of grass with a stick to mark it.

We will never know where the first game of golf was played, although there are lots of places, St Andrews included, which would dearly love to have the accolade.

But wait, perhaps there is an ultimate place that maybe we need to look even further back than the medieval period to find. Perhaps back to . . .

THE ROMANS

Yes, the Romans, and why not?

Of course, when you think of sport and the Romans you almost inevitably think of the Colosseum, gladiatorial combat, people being fed to the lions and the odd emperor getting bumped off or playing some instrument or another while Rome burns. That is a gross over-simplification, of course, because the Romans gave us many things: they gave the world mortar, they showed that with enough man-power you can build a straight road over virtually any type of terrain, they devised a legal system that is used by many countries around the world and they gave us mob rule in sport – they were, after all, the original sporting rowdies.

The question is, could they have given us the game of golf as well?

The reason I ask this is because they did in fact play a game with a ball and clubs, called Paganica. This had nothing whatever to do with clubbing pagans or throwing balls at them, but was a game played with a leather ball that was stuffed with feathers. Players thwacked these balls at targets with crooked sticks.

Does that sound at all familiar? Of course it does. So this may well have been the origin of the game of golf, especially if they found themselves at the farthest reaches of their empire, in a place like Musselburgh where the lie of the land was just crying out for some enterprising centurions to use their building skills and lay out a links.

Mayhap the Romans who settled in Musselburgh left the world a far greater legacy than they expected?

BUT WHAT ABOUT THE CHINESE?

You may ask, am I serious? The answer is decidedly in the affirmative. The Chinese may well have been playing a game that resembled golf as far back as the Song Dynasty (ad 960–1279). That is the thesis of Professor Ling Hongling of Lanzhou University who has discovered documentary evidence in a book called the Dongxuan Records, that shows that this game was played back in ad 945.

His thesis is that golf was invented by the Chinese, then exported to Europe by Mongolian travellers in medieval times, who adapted it to become games like chole, colf or jeu de mail.

GOLF RULES!

So there you are, it is not at all clear who invented this game. One suspects that people in virtually every country have played games with sticks and balls and frankly I don’t really see that it matters who was the first to start thwacking away. It is a bit like trying to work out who invented the bagpipes (we know that the ancient Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans all played a form of bagpipe, but only the Scots developed the Great Highland Bagpipe).

The thing is, although lots of people played games like golf, it was in Scotland that people started using holes on greens and built up a set of convoluted rules that have grown to be more complicated than any legal system in the world. I propose to leave it at that and conclude that even if they didn’t invent the game the Scots deserve to be given credit for being the first to create the organised game of golf.

So there.

Fore!

2

GOLFTIMES

‘History is bunk!’

Henry Ford (1863–1947),

founder of the Ford Motor Company

‘Hell is a bunker in St Andrews.’

Glen Dullan (I have changed his name to preserve some sense of dignity for him),

surgeon and rabbit golfer

All great human activities have accumulated a history and golf has certainly done that, despite the uncertainty of its origins which we discussed in the last chapter. What follows is a quick tour through the years, outlining some of the memorable events that had an impact on the great game.

NOT A GOOD YEAR FOR GOLF – 1457

In 1457 King James II of Scotland (England had to wait until James VI before they could claim a King James I) banned the playing of golf because it interfered with the practice of archery, which was necessary for the defence of the nation.

THE YEAR OF THE FIRST GOLF WIDOW – 1567

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–87) was the legitimate daughter of King James V. Like her grandfather, King James IV, she liked to venture out on the links. She came in for criticism, however, in 1567 when she went out to play golf after the murder of her husband, Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley. It is not recorded whether it was a good round or not.

SUNDAY CLOSING – 1592

In 1592 the town council of Edinburgh issued a proclamation banning the playing of golf on Sunday, because good people should be listening to the sermons, not gallivanting about enjoying themselves.

Then, in 1610, South Leith Kirk Session suggested that anyone caught playing golf on Sundays should pay a fine of one pound, a substantial fine at that time, which would be paid to the poor. The miscreant golfer would in addition have to confess his sins in church.

YOU CAN DO ANYTHING WHEN YOU ARE A KING

In 1608 King James VI became James I of England and immediately, he had a 7-hole golf course laid out at Blackheath.

In 1618 he proclaimed that golf on Sundays was a good thing after all.