Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

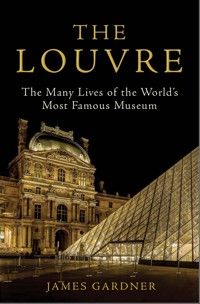

Almost nine million people from all over the world flock to the Louvre in Paris every year to see its incomparable art collection. Yet few, if any, are aware of the remarkable history of that location and of the buildings themselves, and how they chronicle the history of Paris itself-a fascinating story that historian James Gardner elegantly tells for the first time. Before the Louvre was a museum, it was a palace, and before that a fortress. But much earlier still, it was a place called le Louvre for reasons unknown. People had inhabited that spot for more than 6,000 years before King Philippe Auguste of France constructed a fortress there in 1191 to protect against English soldiers stationed in Normandy. Two centuries later, Charles V converted the fortress to one of his numerous royal palaces. After Louis XIV moved the royal residence to Versailles in 1682, the Louvre inherited the royal art collection, which then included the Mona Lisa, given to Francis by Leonardo da Vinci; just over a century later, during the French Revolution, the National Assembly established the Louvre as a museum to display the nation's treasures. Subsequent leaders of France, from Napoleon to Napoleon III to Francois Mitterand, put their stamp on the museum, expanding it into the extraordinary institution it has become. With expert detail and keen admiration, James Gardner links the Louvre's past to its glorious present, and vibrantly portrays how it has been a witness to French history - through the Napoleonic era, the Commune, two World Wars, to this day - and home to a legendary collection whose diverse origins and back stories create a spectacular narrative that rivals the building's legendary stature.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 636

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by James GardnerBuenos Aires: The Biography of a City

First published in the United States of America and Canada in 2020

by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

This hardback edition first published in Great Britain in 2020

by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © James Gardner, 2020

The moral right of James Gardner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 634 7

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 476 3

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother,Natalie Jaglom Gardner29 September 1924–22 February 2019

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction

1 The Origins of the Louvre

2 The Louvre in the Renaissance

3 The Louvre of the Early Bourbons

4 The Louvre and the Sun King

5 The Louvre Abandoned

6 The Louvre and Napoleon

7 The Louvre under the Restoration

8 The Nouveau Louvre of Napoleon III

9 The Louvre in Modern Times

10 The Creation of the Contemporary Louvre

Epilogue

Glossary

Notes

Bibliography

Image credits

Index

PREFACE

In telling the story of the Louvre, I have proceeded simultaneously along three fronts, the architectural, the institutional and the historical. That is to say that the present book describes the evolution of the building known as the Louvre from its earliest foundations as a medieval fortress to the completion of I. M. Pei’s glass pyramid eight centuries later. But the book also considers the institutional genesis of the great museum that has now inhabited that structure for over two hundred years, animating it as a soul animates a body. Finally, and no less essentially, the book explores the crucial role that the Louvre has played in the history of France and its ruling dynasties, from the time of the Third Crusade, through the Revolution, to the Second World War and beyond.

Although this tale is well worth telling, it is also one of nearly incalculable complexity. Architectural history is to art history as three-dimensional chess is to the standard version of the game. In general, a painting or sculpture is created by one artist in a fairly abbreviated span of time and it remains in that final condition, shielded from the elements, for as long as its material foundations hold up. But a building, especially a great building, is often a labor of centuries, engaging the talents of generations of architects and codifying in stone the often discordant whims of several great dynastic families. It is subject to constant attack from the elements, and not infrequently from the fusillades of invading armies and the vicissitudes of siege warfare.

Perhaps no single structure on the planet exhibits this complex and protracted genesis as well as the Louvre, which, for more than eight hundred years, has been in a process of becoming. What we see today—not counting what has been destroyed beyond recall—is the result of some twenty discrete building campaigns over five hundred years, and indeed, the building’s history goes back three and a half centuries before the construction of the earliest structures that are now visible above ground.

But traditionally architects and their patrons seek to belie such troubled gestation and to persuade visitors that they stand before a serenely unified project born of a single building campaign. And that is how most visitors see the Louvre, and how, for a long time, I too saw this incomparable palace. I was aware that there were stylistic disparities among its parts and that it had emerged over a period of centuries. But one day, as I was entering the grounds of the Louvre for perhaps the hundredth time, it suddenly came home to me that I knew almost nothing of the story behind what I was seeing. As I began to look into the matter, my initial curiosity grew upon itself, resulting in the book that you now hold in your hands.

In several respects this book is antithetical to the one I wrote immediately before it, a history of the city of Buenos Aires. That book engaged a massive subject—an entire city—that had been relatively little studied and, to the extent to which it had been studied at all, in a rather unsystematic, even shoddy way. By contrast, the focus of the present book is a single object—although, admittedly, one of the largest on earth—every square inch of which has been scrutinized by the most eminent and exacting art and architectural historians, not only in France, but throughout the world. My skills and training being those of a cultural critic rather than a researcher in recondite fields, I freely admit that I have left archival inquiries to the many scholars who are far more practiced and proficient in such pursuits. I am also delighted to acknowledge my debt to the three-volume Histoire du Louvre, edited by Geneviève Bresc-Bautier and Guillaume Fonkenell, which appeared at precisely the moment when I began writing my book. Engaging the talents of nearly a hundred scholars and extending to nearly two million words, that book is a summa of archival research—intended mainly for scholars in the field—into every imaginable aspect of the history of the Louvre as a building and an institution.

In the interests of housekeeping, the reader will allow me to make several somewhat disconnected points. The first is that, for the sake of consistency, I have numbered the floors in the Louvre, and elsewhere, after the European fashion, rather than the American: the lowest externally visible part of a building is its ground floor, followed by the first floor (which in the United States is called the second floor). The Louvre thus has three levels (not counting several levels below grade): the ground floor, the first floor and the second floor.

Next, it should be stated that the entire western side of the Louvre—as it opens outward to the Champs-Élysées and the Arc de Triomphe—was once occupied by a great palace, Les Tuileries, that was integral, and physically connected, to that architectural complex that we call the Louvre. This palace burned to the ground under the Communards in 1871. Of necessity, I refer to it frequently in the course of the present narrative, but far less for its own sake than for its influence on the evolution of the Louvre as we know it today.

A book of this sort necessarily mentions a great number of paintings, sculptures and architectural elements, more than could be conveniently included among the illustrations. But if this book has a generous complement of images, it has been written in the full awareness of the new realities of the internet: an illustration of every work of art mentioned in the book can be found with relative ease online, and in a higher, crisper resolution than any printed book could achieve. The reader is therefore encourged to seek these images at that bountiful source.

In writing this book, I have more people to thank than could be reasonably named in the present context, and so I will be brief. My gratitude goes first to my editors at Grove Atlantic, Joan Bingham and George Gibson, for their unfailing patience, sensitivity and enthusiasm for this project. Also at Grove Atlantic, I must thank their editorial assistant Emily Burns, the managing editor Julia Berner-Tobin, the copyeditor Jill Twist, the proofreader Alicia Burns, the art director Gretchen Mergenthaler, who designed the book’s splendid cover, and my publicist John Mark Boling. My thanks as well to my gifted agent, William Clark, a committed Francophile who brought me to the attention of Grove Atlantic. I would also like to thank the staffs of the Frick Art Reference Library and especially of the Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum: it is a great but rarely appreciated testament to the cultural standing of New York City that two of the finest art history libraries in the world should stand within ten blocks of one another along Fifth Avenue. I must also express my gratitude to Colin Bailey, director of the Morgan Library and an expert in French art, for so generously agreeing to review this manuscript, as well as to Iris Moon, assistant curator of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who kindly reviewed the chapter on Napoleon Bonaparte. It hardly needs to be stated that any remaining errors are entirely my own. My thanks as well to my niece Nadya Gardner, who took the photo of me that accompanies this book. Finally, I must thank the staff of the Hotel Brighton, my home in Paris, for taking such good care of me while I was researching this book. There could be no greater inspiration than to look out the window of my room and, from across the Jardin des Tuileries, to see the Louvre, on a fine morning in early spring, spreading out before me dans sa gloire.

INTRODUCTION

Before the Louvre was a museum, it was a palace, and before that a fortress, and before that a plot of earth, much like any other. In French there is a term for such a place, un lieu-dit, for which no real equivalent exists in English. This term refers to an area that is familiar to the inhabitants of a region and that may have a name, but, whether populated sparsely or not at all, it has no official, legal recognition. Through what would become the three main open spaces of the modern Louvre—the Cour Carrée, the Cour Napoléon and place du Carrousel—human beings passed and repassed for thousands of years before the ancestors of the Celts and Romans ever began their migration from the Eurasian Steppe westward to the territory of modern France.

We know this because, simultaneously with the vast construction at the Louvre in the 1980s, resulting in the museum we know today, extensive archaeological work was carried out in those three main open spaces. The site of the Cour Napoléon yielded up pottery dating back more than seven thousand years, while the skeletal remains of a man who died over four thousand years ago were unearthed near the Arc du Carrousel and what is now the underground bus depot of the Louvre. Toward the end of the Gallo-Roman period, in the first centuries of the common era, two farms, one in the Cour Napoléon, the other at the site of the place du Carrousel, raised cattle and pigs, and abounded in plum, pear and apple trees, as well as vineyards.

At some point, long before King Philippe Auguste of France decided, in 1191, to build a fortress on this spot of land, the entire area acquired a mysterious name, le Louvre, which has defied all efforts to decipher it. What we do know is that Philippe did not name his fortress le Louvre or anything else, since it was really nothing more than a piece of military infrastructure designed to shelter a garrison. Standing outside of Paris at the time of its construction, it merely came to be known by the name that, for centuries, human beings had called the land where it stood: le Louvre.

I emphasize the “placeness” of the Louvre in part because everything about it today seems designed to reject and cover up its infinitely humble, elemental origins. Certainly since the time of Louis XIV in the late seventeenth century, if not before, the Louvre has contrived, both in its general design and in its specific details, to appear almost superhuman. Nearly half a mile long from end to end, it is one of the largest man-made structures on the planet, so large that no human eye can take in its entirety from any angle on the ground. But it defies our common humanity in other ways as well. Although much of the structure that the visitor sees today is from the seventeenth century, most of it was either built, rebuilt, or reclad in the nineteenth century: in this sense, the Louvre is a nineteenth-century project, even if its formal components owe a great deal to the architectural aesthetics of two centuries before. At its completion in 1857, the Louvre was the defining architectonic triumph of Napoleon III, if not the material embodiment of the entire Second Empire. Everything about French culture at that time had such superhuman longings. These aspirations are expressed both in the peerless symmetries of the Cour Napoléon and in the extravagant neobaroque language in which the entire complex was reconceived under Napoleon III. There is a hardness, a massiveness to the Louvre, with its burnished railings and marble floors and gilded capitals, that seems to repudiate human frailty. It is the virtuosic expression of something that reaches deep into French culture since the time of the Sun King: a tyrannous, all-conquering discipline, expressed in the faultless couplets of Racine and Boileau and the ballet en pointeof Jean-Georges Noverre, in the culinary precision of Carême and Escoffier, and in the obsessive grammatical precision of Mallarmé and Marcel Proust. Perhaps more than any other building ever made, the Louvre stands as an implicit reproach, a programmatic rejection of the art and architecture that the West favors today, with its asymmetries, its puerile rebellions, its clamorous proclamation of its own insufficiency. It is as though, in the pavilions and colonnades of the Louvre, civilization itself stood in pitched battle not only with human nature in all its weakness, but also with mother Earth, with all those clumps of grass and viscous clay that once occupied this parcel of land and that continue to lie beneath it, waiting for the moment when, at some point in remote posterity, they will regain their former empire.

The place that is the Louvre occupies a position of radical centrality, or so it would have us believe. If Paris is figuratively the center of the world—as it certainly seemed to be in the nineteenth century—the Louvre is the center of Paris. This is literally true. The circumference of the city—represented by the highway known as le Périphérique—spins around the Louvre like a pinwheel at a radius of about three miles in every direction. But here again, the origins of the Louvre belie this assertion of centrality. Today there is as much Paris to the west of the Louvre as to the east. But when the original fortress was built around 1200, it was a military outpost just west of the newly built walls of the city. This is to say that, by strategy and design, the Louvre was eccentric to Paris, which lay entirely to the east. And the Louvre would preserve that status until a new wall, built around 1370, finally assimilated it into the city. But even then, the Louvre stood at the western edge of the capital and would remain there for the next five hundred years.

Most of the great events that influenced the histories of England and the United States did not occur in London and New York, respectively, but on some field of battle in open country. And yet, there is probably no city in the world in which history—the history not just of France but of Europe and beyond—played out more consistently than Paris. By the same token, there is no part of Paris denser in historical consequence than the Louvre. This heritage will surprise many visitors to the museum, who may not even realize that it ever served any other function than that of a repository of great art. In fact, although the Louvre has existed for more than eight hundred years, it has been a museum for only a little over two hundred of those years.

This fact is not to deny, of course, the importance of the Louvre in the history of art. The museum’s role in creating the grand narrative of art history should be fairly obvious: the Louvre was the first and is almost certainly the greatest encyclopedic museum in the world, bringing together the art of almost every age and almost every region. What is less widely known, however, is that the Louvre, in addition to being a veritable nursery of architectural innovation, was more directly responsible for the actual production of Western painting and sculpture than any other institution yet conceived. Not only did Nicolas Poussin show up every day to paint the ceiling of la Grande Galerie (although he didn’t get far before he abandoned a task he clearly saw as a distasteful burden): for more than a hundred years after Louis XIV abandoned Paris for Versailles in 1682, the Louvre was repurposed as an academy where the greatest artists of France were given studios, free of charge, in which to create whatever they wished. Here the charm of local specificity asserts itself. We can point to the very spot in the northern wing of the Cour Carrée where Jean-Honoré Fragonard painted so many of the world’s most endearing paintings. On the first floor of the southern wing, Chardin and Boucher were hard at work in what are now the Egyptian Galleries. The concept of the Salon (the Salons of 1759 and 1761, for example), which lives on today in the Whitney Biennial and the Biennale di Venezia, was born in and named for the Salon Carré, a few steps to the right of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, where the works of Giotto and Duccio now appear.

But it is one of the paradoxes of the Louvre that, although it is among the most frequented places in the world, it is also one of the least understood. Such confusion is hardly surprising, since there is probably no one structure—or more accurately, no complex of structures—in architectural history whose gestation was as protracted or convoluted. What we see today is the result of no fewer than twenty distinct building campaigns that drew on the very diverse and unequal talents of scores of architects over eight centuries. And yet, because there is no glaring disparity among the many parts of this complex, it rarely presents itself as a question to the common visitor. Most tourists enter the Louvre through the Pyramide, never realizing that everything they see dates to the 1850s or soon after. In a strictly historical sense, then, they are hardly seeing the Louvre at all, at least not what a Parisian of 1600 or 1800 would have understood by the term.

In fact, what they are seeing can be divided conceptually into four main parts. The Palace of the Louvre, properly understood, consisted of the four wings that now make up the Cour Carrée, occupying the eastern extremity of the Louvre complex. For most of its history, when people spoke of the Louvre, they meant this square structure, and only this. But if you turn west, with the Pyramide and the Cour Carrée at your back, you will see the Arc de Triomphe several miles in the distance, at the top of the Champs-Élysées. You should not be seeing the Arc de Triomphe in the distance, however, and this brings us to the second component of the Louvre: the reason you can see the arch at all is that the Tuileries Palace, which was begun in 1564 and should be blocking your view, was burnt to the ground by revolutionaries during the Paris Commune of 1871. But although the Tuileries Palace no longer exists, almost every part of the Louvre that you see today was created in response to it. For example, to the south lies the third component of the Louvre, a stunningly long and narrow building, half a kilometer in length and known as the Grande Galerie. For most visitors to Paris, even for most Parisians, this is the Louvre, because it contains those paintings by Leonardo da Vinci and other Italian masters that they have come to see. And yet, this gallery was created as little more than a covered passageway leading between the Louvre Palace and the Tuileries Palace, which thereafter became part of the Louvre complex. As for everything else you see, the entire northern half of the Louvre (except for one section built around 1805) did not exist before the 1850s. Instead, this entire area was filled for centuries with churches, a hospital and many houses great and small, some of them little better than huts.

In chronicling the dynastic and urbanistic forces that influenced each stage of the Louvre’s evolution, as well as the myriad events that took place within the walls of the fortress, then the palace, and later the museum, I will argue that the Louvre is as great a work of art as anything it contains. It would be fairly easy to argue that the façades of the Aile Lescot and the Colonnade all the way at the eastern end of the Louvre should be so considered. But I foresee some resistance when the discussion turns to the Escalier Daru or to the design of the interior of the Grande Galerie. In making this argument, I offer up a totalizing view of the Louvre complex, every part of which is something one should know about. Every element of it that crosses one’s line of vision potentially deserves attention, not least the murals of Romanelli and Le Brun that adorn the ceilings of the museum, but that tend to be overlooked because they do not sit politely in a frame.

Comprising nearly four hundred thousand objects from fifty centuries and two hundred generations of human culture, the Louvre is almost certainly the greatest collection of human artifice ever assembled in one place. And yet those objects are not simply there. Vast, overarching historical and cultural forces brought each of those objects into the galleries of the museum. The Louvre is, among other things, a vast, indiscriminate cocktail of princely collections purchased or purloined over the course of centuries. Not all of it is good, which is of some interest in itself, shedding light as it does on the ever shifting and infinitely unstable progress of taste. More importantly, every work of art that it contains has its story. The Mona Lisa is there because François I bought it from Leonardo da Vinci shortly before the painter died. As regards Raphael’s great Saint Michael Routing the Demon, Pope Leo X gave it to François I in hopes that he would return the favor by invading the Ottoman Empire. And Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana, one of the largest works ever painted on canvas, occupies a wall of the Salle des États because Napoleon Bonaparte stole it from the Venetians and never gave it back. These and four hundred thousand other stories like them all come together to form the Musée du Louvre, the latest chapter, and surely not the last, in the evolution of that little corner of the earth that rests upon the right bank of the Seine.

- 1 -

THE ORIGINS OF THE LOUVRE

Most visitors to the Louvre come to see the Italian paintings and especially the Mona Lisa. This part of the museum, the Aile Denon, is flooded with light that pours in from the ceiling and the windows that look out onto the Seine. Even the gilded frames seem to give off light. To reach it one must ascend, climbing the grand Escalier Daru and turning right at the Winged Victory of Samothrace, before emerging into the brilliance of the Salon Carré.

But there is another part of the Louvre, rather less frequented, that seems to belong to a different world. Although it does indeed receive its share of visitors, it is unlikely to be the reason for which they have come to the museum. To reach it, one descends into the earth, into something like twilight or even night, to find the remains of the original Louvre: the fortress that Philippe Auguste built at the end of the twelfth century and the palace into which it evolved under Charles V, late in the fourteenth century.

For fully two hundred years after the last visible traces of the medieval Louvre were razed to the ground in 1660, these subterranean realms were completely forgotten. Not until 1866 did the archaeologist Adolphe Berty, on a hunch, begin to excavate the site. He discovered the intact remnants of the soubassement, the twenty-one-foot-high foundation of what had once been the eastern and northern walls of the palace, hidden beneath the modern Cour Carrée. But these stunning discoveries would soon be forgotten by all but a few scholars, not to be seen again for another century. Only when the great work began on the Grand Louvre, that pharaonic labor initiated by President François Mitterrand in the mid-1980s, was a systematic excavation finally undertaken, not only of the original palace, but also of the Cour Napoléon, where I. M. Pei’s Pyramide now sits, and—several hundred meters to the west—the area surrounding the Arc du Carrousel.

The circumstances under which the Louvre came into being, as well as the reasons for its construction in the first place, are intimately involved with the form and nature of Paris itself at the end of the twelfth century. Consider the magnificent opening of Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel Notre-Dame de Paris (better known in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame): “Today it is three hundred and forty-eight years, six months and nineteen days since the Parisians awoke to the clamor of all the bells resounding mightily in the threefold enclosure of the Town (la Cité), the University and the City.”

There is nothing arbitrary in that wording. “The Town, the University and the City” succinctly sum up the tripartite division of Paris from medieval times down to the French Revolution (Hugo was writing about the 1480s). The town occupied the Île de la Cité, the largest island in the Seine and the natural bridging point between its right and left banks. This island had been the center of government and religion as far back as the Roman Empire, when, seven hundred feet west of today’s Notre-Dame, a palace was built that would serve for a thousand years as the official residence of the kings of France. Immediately to the south, on the left bank, rose the university, established in the year 1200 through the consolidation of several preexistent monastic schools. And finally there was la ville, the city. Not accidentally, Hugo mentions this part last. It had neither the royal and ecclesiastical glamour of the Île de la Cité nor the prestige of the schools and monasteries of the Left Bank. And yet, by the time the Louvre, in its earliest form, was completed around 1200, la ville accounted for most of Paris. This was its center of population and seat of commerce, the home of a restless and enterprising bourgeoisie. For centuries to come, the growth of Paris would occur here, while the Left Bank largely stagnated. And the immoderate growth of this part of Paris forced the king, Philippe II, to build the fortress of the Louvre.

Known to history as Philippe Auguste, he was one of the ablest and most powerful monarchs of the Capetian dynasty that ruled France from 987 to 1328. But when he ascended the throne at fifteen, in 1180, few kingdoms were in as weak or perilous a state. The realm he inherited was almost entirely blocked from the Atlantic by the Angevin kings of England, Henry II, Richard the Lionheart and John Lackland, who controlled the western third of modern France from Normandy down to the Pyrenees. To make matters worse, a wedge of English-controlled land jutted eastward along the Massif Central, cleaving his kingdom in two. Meanwhile, the eastern third was in the hands of the Duke of Burgundy, hardly a trusted ally. All told, the territory that Philippe ruled at the outset of his reign constituted barely a third of modern France, and even this was chipped away at many points by ecclesiastical lands ultimately subject to the pope in Rome. By the end of his forty-three-year reign, however, he had wrested most of Western France from the English, and greatly increased the crown lands, the territory that belonged to him outright, the source of his power and wealth.

Throughout his reign, Philippe was constantly on the move. In addition to embarking on the Third Crusade to the Holy Land and vanquishing the English at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, he centralized the administration of his kingdom and crushed the Albigensian heretics in Provence. And yet, some of his greatest contributions were made in Paris itself. At this time the capital was undergoing an energetic urban development that, relative to its earlier condition, could be compared to its expansion under Henri IV in the seventeenth century or under Napoleon III in the nineteenth. Although it is common to treat the capital, and even the French monarchy itself, as weak and marginal at this time, no city of the second rank could have built one of the largest and greatest cathedrals in Christendom, Notre-Dame de Paris. Louis VII had begun construction in the 1160s and Philippe Auguste, his son, substantially completed the work by 1200. At this time as well, the convent schools on the Left Bank were consolidated into what would become one of the finest universities of Europe, the Sorbonne. Meanwhile there could be no greater testament to the vigor of the Right Bank than the new commercial area of les Halles, which Louis VI created in 1137 and Philippe Auguste greatly expanded early in his reign. At the same time, he enlarged the nearby cemetery known as the Cimetière des Innocents, thus creating one of the largest open spaces in a city that had very few of them. And for the first time, he paved over some of the city’s principal streets. As cause and consequence of these actions, in the year 1200 the city’s population surpassed one hundred thousand for the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire.

It was precisely this frantic pace of development that moved Philippe to construct a great wall, or enceinte, more than three miles in circumference, around his capital. And the Louvre itself was nothing more or less than a consequence of the wall. This structure was to be but a small part of a vast system of fortifications that would comprise twenty castles throughout France. Because an English onslaught was most likely to come from the northwest, Philippe began to fortify the Right Bank, the northern half of the city, in 1190, just before he embarked on the Third Crusade. This part of the wall was completed in 1202. The less urgent fortification of the Left Bank began in 1192, shortly after Philippe’s return, and was built by 1215. In one of the ironies of history, however, Philippe Auguste’s massive system of fortifications ultimately proved unnecessary, since he conquered and annexed Normandy in 1204, effectively ending the English threat.

Formed of mortar and rubble and faced with blocks of dressed limestone, the wall of Philippe Auguste was ten feet wide and twenty-five feet high. It was punctuated, at intervals of two hundred feet, by seventy-seven towers, while four massive towers, each more than eighty feet tall, guarded the points where the ramparts met the Seine. Although a few remnants of the wall are still visible on the rue Clovis and rue des Jardins Saint-Paul, as well as in some of the basements, back alleys and parking lots of the Left Bank, it has otherwise left little trace beyond what we can infer from certain lingering street patterns.

As impressive as these defensive walls surely were, one great tactical problem went unaddressed: the English could simply float down the Seine, slip through the iron chains suspended across the river from the Tour du Coin to the Tour de Nesle—the two large defensive towers to the west—and stand a good chance of entering the city unobserved. And so Philippe Auguste decided, soon after he returned from the Holy Land in 1191, to protect this weak flank with a fortification that initially stood, not in Paris itself, but on a plot of land just beyond the western border of the walls that now defined the capital. For centuries, the people of Paris had been in the habit of referring to this area as le Louvre. And so, by the early thirteenth century, shortly after its construction, the fortress was already being called le manoir du louvre près Paris, roughly translated as “the castle in the area known as ‘the Louvre’ next to Paris.”1

Perhaps the most intractable mystery of the Louvre has to do with the origin and meaning of its name. Over the centuries many hypotheses have been proposed, and all of them appear to be wrong. Of the two most prevalent explanations, one was put forward by the seventeenth-century French antiquary Henri Sauval, who claimed to have found an ancient Anglo-Saxon glossary—which no one since has ever seen—that contained the word loevar, which apparently meant “castle” in the Saxon language. (It is also worth noting that many of Sauval’s contemporaries firmly believed that the Louvre was not five hundred years old at the time of his writing, but well over a thousand and that it had been built by the Merovingian king Chilperic, who died in 584.) A more popular but even less plausible derivation is based on the similarity between the words louvre and louve, the latter word being French for she-wolf. According to this theory, the land now occupied by the Louvre was once infested by wolves or, alternatively, was used to train dogs to hunt them down.

What is important, and often overlooked, is that the Louvre was never formally designated as such, but gradually assumed the name of a preexisting feature of the right bank of the Seine as it flowed through medieval Paris. Thanks, however, to the inexhaustible industry of the first archaeologist of the Louvre, Adolphe Berty, whose six-volume Topographie historique du vieux Paris (1866) is a monument of nineteenth-century science, it is certain that the area was designated Luver in 1098, nearly a century before the Louvre itself existed, and that as early as the ninth century, the name Latavero was applied to this part of the French capital. With his punctilious reverence for the truth, however, Berty claimed to have no idea what the word meant, although he suspected that it was of Celtic origin. In any case, he recognized that the form Latavero precluded any connection to louve or to its Latin cognate lupa.2 As for the castle itself, it appears to have been known initially as the tour neuve, or in the Latin of Guillaume le Breton, turris nova extra muros (the new tower beyond the walls).3

This area of Paris, directly to the west of the wall of Philippe Auguste, lay near what in ancient days had been the main road through the right bank of the Seine: it lives on today as the rue Saint-Honoré and the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Although traces of farming, burial and the occasional hut came to light through excavations carried out during the creation of the Grand Louvre in the 1980s, the area largely remained in its natural state until Philippe Auguste came to power.

Before his accession, nothing of note had ever happened in this part of Paris, with one crucial exception. Between 885 and 887, the Normans, a Viking clan, descended from Scandinavia into the Île-de-France region and laid siege to the area of today’s First Arrondissement, west of le Grand Châtelet. Included therein was the Church of Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois, directly across from today’s Colonnade du Louvre, the museum’s easternmost extension. These nomadic invaders, however, had no interest in conquering the city: they wanted only to extort tribute from the Carolingian emperor Charles the Fat. This he was happy enough to give them, before sending them on their way to plunder the neighboring region of Burgundy. Once the invaders had left, the Parisians responded by erecting their first new city walls since antiquity, extending roughly one kilometer along the Right Bank from the Church of Saint-Gervais in the Marais to Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois. The western limit of the wall, like that of Philippe Auguste’s wall three centuries later, lay just east of the modern Louvre.

Philippe was well aware that, by the last quarter of the twelfth century, a change had come over Paris. After nearly a thousand years of torpor or decline, the city had begun to expand to the north and to the east, but also, in a very limited degree, to the west. When Thomas à Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury, was murdered in his cathedral in 1170, a wave of revulsion and sorrow reached many parts of Europe, including Paris. Perhaps only a few months later, but decades before the fortress of the Louvre had even been conceived, a church was dedicated to him just beyond where the fortress would rise thirty years later, on the land where I. M. Pei’s Pyramide stands today. In 1191, a decade before the Louvre was completed, perhaps before its cornerstone was even laid, a document referred to this church as the hospital pauperum clericorum de Lupara, the shelter of the poor clerics of the Louvre.4 It was more commonly called Saint-Thomas du Louvre, and it remained standing into the 1750s. That church appears to be the first substantial structure ever built on the land now occupied by the Louvre Museum.

* * *

Philippe Auguste, who ruled France from 1180 until his death in 1223, was more renowned as a warrior king than as a patron of the arts. Although he chartered the University of Paris, established churches and granted land to monasteries, it is difficult to find, amid his full and tumultuous life, any avid pursuit of culture as such, any aliveness to the life of the mind, any alertness to the refinement of a building or the charm of a painted manuscript.

Not surprisingly, then, his Louvre was no thing of beauty and was never intended to be. Standing just beyond the western limit of Philippe’s new walls, ninety miles from the English Channel and thirty-five from lands occupied by the bellicose king of England, its simple, uninflected square-massing was not really meant to be seen at all, except by the marauding English troops, whom it was intended to cow into retreat. Other than the soaring donjon—its central tower—that rivaled the belfries of Notre-Dame, the bulk of the fortress was largely invisible from inside the capital, especially from the right bank, where the many intervening structures would have made it difficult to see. The castles and fortifications of France are among the finest works of medieval architecture: one thinks of the hard splendor of the walls of Carcassonne or the combined solidity and grace of Pierrefonds in Picardy. But the Louvre of Philippe Auguste knew nothing of such presence or grace. No contemporary image of it survives, and what we know of it is only what can be inferred from the archaeological remains of its successor, the palace of Charles V, completed two centuries later. From this evidence it appears to be the progenitor of all those drab barracks, blockhouses and flak towers of a later and far less chivalrous age.

Its four massive walls, rising forty feet, were entirely bereft of ornament. To the north and east were curtain-walls, purely defensive structures that extended—like curtains—between the towers. To the west and south, the corps-de-logis—the living quarters as opposed to the fortifications—provided shelter for a small garrison of several dozen men and their commanding officers, but the accommodations could hardly have been pleasant: beyond the narrow slits in the walls, few windows admitted light into this sullen fortification. Of its two entrances, one faced south, toward the Seine, while the other faced east, toward the city. Visitors entered each through a gate flanked by two cylindrical towers. With a tower at each corner and at the midpoint of the southern and western walls, the fortress had ten in all, crowned with a toit en poivrière, a pepperpot dome, that shielded the sentries from the elements and from incoming fire. The waters of the Seine flowed through a moat that surrounded the fortress on all sides except to the east, and untilled fields extended just beyond the northern and western walls.

The most distinguishing feature of the fortress, perhaps its only one, was the keep, or donjon, la Grosse Tour, whose cylindrical mass rose nearly one hundred feet and could be seen, for centuries to come, from almost any point in Paris. It occupied the center of the fortress and was separated from the rest of the interior by the deep, waterless moat that encircled it. The Grosse Tour served as a prison for high-value captives. In 1216, only a few years after its completion, it received its first important prisoner, Ferrand, Count of Flanders, an ally of the English who was taken prisoner at the Battle of Bouvines. In what appears to be the earliest mention of the Louvre that we have, this event is described in Guillaume Le Breton’s Philippide, a poem in Latin hexameters devoted to the reign of Philippe Auguste and completed before 1225. In its second book, the author vividly describes Ferrand’s arrest:

At Ferrandus, equis evectus forte duobus . . .Civibus offertur Luparae claudendus in arceCujus in adventu clerus populusque tropheumCantibus hymnisonis regi solemne canebant.

But Ferrand, led on perchance by two horses, was delivered to the citizens [of Paris] to be imprisoned in the fortress of the Louvre. At his coming, the clergy and the people solemnly sang hymns to the king in celebration of his triumph].5

The drab utilitarianism of the fortress of Philippe Auguste stands in stark contrast to the Louvre that we know today, where ornament often seems to take on a life of its own. But even though the differences are obvious, even though not a stone of the original structure survives above ground, still the ghost of the medieval building can be summoned from the Corinthian pillars, the oculi and the sculpted swags of the modern Cour Carrée, which rise over the site of the original fortress. For the scale of the Louvre, so arbitrarily determined eight centuries ago, remains embedded in much that we see today. Each side of the original building was 236 feet across, dimensions that survived its transformation into a medieval palace and then into a Renaissance palace. And even when Louis XIII decided to enlarge the structure to its present dimensions around 1640, his architect Jacques Lemercier simply recreated the original building a little to the north, linking the two identical structures by means of the Pavillon de l’Horloge that we see today. The influence of the fortress extends nearly half a mile to the westernmost parts of the Louvre, whose height and width are largely determined by the fortress of Philippe Auguste. The fortress was exactly one-quarter the size of the modern Cour Carrée, fitting into the southwest quadrant in such a way that its northeast corner rose over the spot now occupied by the central fountain.

If this aesthetic assessment seems unduly harsh, let it be said that what little survives of the original structure, especially the twenty-foot-tall soubassement, or base, in the Aile Sully, has been well made. Its dressed stone is more finely cut and finished, perhaps, than was necessary for a fortification that few Parisians would ever see, especially since much of what survives lay submerged beneath the waters of the Seine. One historian has stated that “the Louvre, together with [Philippe Auguste’s] other constructions, fully merits inclusion in the pantheon of French castle architecture.”6 Philippe’s Louvre also influenced subsequent castles: Seringes-et-Nesles and Dourdan, with their corner and median turrets set into a square enclosure, follow the model of the Louvre in their rejection of the generally irregular footprint of most earlier castles. Even on the outskirts of Paris itself, this influence persisted one and a half centuries later in the Château de Vincennes, not to mention the legendary Bastille itself.

Presumably for reasons of defense, the Louvre fortress did not border the Seine, but was recessed nearly three hundred feet to the north. For centuries to come this decision would bedevil the monarchs and masons of France. As we will see in later chapters, the creation of a second palace, the Tuileries, half a kilometer to the west, and the ambition to join these palaces by means of the Grande Galerie—which now houses the Louvre’s collection of Italian paintings—resulted in all kinds of odd asymmetries. A solution, and a fine one, was found only in the 1850s, with the completion of the Nouveau Louvre under Napoleon III. Still, that original decision to recess the fortress from the Seine is the reason why, to this day, the Cour Carrée does not feel organically connected to the rest of the Louvre, and it is also why, in moving from one building to the other, the uninitiated visitor is apt to feel that he is passing through a labyrinth.

* * *

In the century and a half between the completion of Philippe Auguste’s fortress and Charles V’s decision to transform it into a royal palace, the Louvre was visited only rarely by the nomadic kings of France, and it sustained few modifications. Other than incarcerating prisoners of rank and holding jousting tournaments, it served little function, since the Anglo-Norman threat had receded and the threat of the Plantagenets had not yet emerged. One section of the fortress was placed at the disposal of the royal treasury, and another part was allocated to the manufacture of cross-bows.

But the French monarchy gradually came to see the advantages to being closer to the ville of Paris, the Right Bank, that center of its enterprising bourgeoisie. As the royal bureaucracy became ever larger at the Palais de la Cité, the Louvre began to seem like a quieter, more convenient alternative to the bustle of officialdom on the Île de la Cité. Philippe Auguste’s grandson, Louis IX, better known as Saint Louis, ordered the construction of a chapel in the southwest corner of the fortress, at the southern end of what is now the Salle des Caryatides. Underneath that chapel was a crypt whose remains were discovered in the 1880s and are now part of the medieval excavations in the Aile Sully.

In short order the fortress engendered a small town—later known as the Quartier du Louvre—where before there had been little or nothing. As this area evolved, it did not become a typically medieval tangle of streets, such as one still finds elsewhere in Paris in the Marais or the Quartier Latin, but a fairly orderly development. Its two main avenues, stretching north to south from the rue Saint-Honoré to the Seine, were the rue Saint-Thomas and the rue Froidmanteau, the latter possibly older than the fortress itself. The rue Saint-Thomas extended roughly from the Pavillon Denon to the Pavillon Richelieu, the rue Froidmanteau to its east, from the Pavillon Daru to the Pavillon Colbert. As a direct consequence of the fortress’s construction, five other streets came into being: the rue Beauvais, which ran parallel to its northern edge, and the rue Jean Saint-Denis, rue du Chantre, rue du Champ-Fleury and rue du Coq, all extending northward from the rue Beauvais. Little trace of these streets remains today. The easternmost, the rue du Coq, was widened, and, now reborn as the rue de Marengo, leads up to the Pavillon Marengo, which stands at the center of the Cour Carrée’s northern façade. By the time Philippe Auguste died in 1223, Adolphe Berty writes, “he was able, from the height of the towers of his Louvre, to contemplate at the foot of the castle an entire new quartier whose buildings . . . were sufficiently numerous to reveal no trace of the tilled earth that was there before.”7

Some idea of the emerging bustle of this new district will be found in Christine de Pizan’s description, less than two centuries later under Charles VI, of “the multitude of people and diverse nationalities, princes and others, who arrive from all over chiefly because [the Louvre] is the main seat of the noble court.”8 Most of the resulting building stock was fairly humble, unlike the proud aristocratic dwellings that arose there at the end of the next century. As for the expansive area west of the rue Saint-Thomas, all the way to the modern place de la Concorde, it largely remained arable land, although tile factories—required, as a potential fire hazard, to lie at some distance from the wooden houses that predominated in medieval Paris—began to appear there under Louis IX.

The biggest single structure on the grounds of the modern Louvre, other than the palace itself, was the Hôpital des Quinze-Vingts (the Hospital of the Three Hundred) founded by Saint Louis around 1260 and so named because it had a capacity of three hundred beds for patients who were blind and poor. Situated west of the rue Saint-Thomas du Louvre it stretched from the rue Saint-Honoré south to what is now the Pavillon de Turgot, built by Napoleon III in the 1850s. It comprised a church and chapel as well as a small cemetery. As such it was one of three burial grounds in what is now the Cour Napoléon, together with those of the Churches of Saint-Nicolas and Saint-Thomas. Among those buried—several centuries later—in the last of these churches was Pierre Bréant, “barber to the great man and powerful prince the Duc of Bretagne,” as well as Robert Rouseau, “priest, native of the islands of the Philippines and, during his lifetime, a canon of this church.” Perhaps the most important tomb belonged to Mellin de Saint-Gelais, an important figure in the history of French poetry, who may well have introduced the sonnet into France.9

* * *

We know little if anything about the appearance of Philippe Auguste: he hardly emerges from the shadows of the Middles Ages, and his main chronicler, Guillaume Le Breton, comes closer to hagiography than to history. But as regards the appearance of Charles V and his wife, Jeanne de Bourbon, we are singularly well informed: a life-sized statue of each ruler—made during their reign—now stands beside the Cour Marly, in the Richelieu Wing of the Louvre. Especially the king, with his flabby cheeks and weak chin, bulbous nose and oddly parted hair, seems true to life, looking weary and older than his years. Since he was only forty-two when he died in 1380, the statue could not have been made long before his death. Together, the paired images represent an important example of the late Gothic naturalism that prefigures the advances of Jan Van Eyck and the other Flemish masters fifty years later. These crowned figures, which retain traces of their original polychrome, are thought to have stood high up on the eastern façade of the Louvre palace, the part that faced the city of Paris and would be instantly seen by all who entered. There the pair remained for nearly three centuries until, in 1660, Louis XIV ordered the destruction of the last visible remnants of the medieval Louvre.

Charles V, who ruled from 1364 to 1380, had the demeanor of a scholar, but the circumstances of the realm that he inherited, especially early on, forced upon him the role of a man of action. He was the son and successor of Jean II of France, who ruled from 1350 to 1364 and sired four of the greatest artistic patrons of the later Middle Ages: in addition to Charles, these were Louis I of Anjou, Jean, Duc de Berry and Philippe II of Burgundy. Not the least of Jean II’s distinctions is a portrait of him, now in the Louvre, that was painted at the outset of his reign in 1350. Depicting him in profile, with a mane of red hair and a scruffy beard against a golden background, this panel has the distinction of being, for all we can determine, the first painted portrait of an individual human being to survive since the end of antiquity. It is not, of course, the direct progenitor of the Mona Lisa and of portraits painted by Raphael and Rembrandt, but it is the earliest example we have of a genre that would prove supremely important for the future of Western art.

Statues of Charles V and his queen, Jeanne de Bourbon, c. 1380, that adorned the eastern entrance to the original Louvre, which he converted from a fortress into a palace. Now in the Aile Richelieu.

But Jean was destined to come to a bad end. He was defeated by Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince of England, at the Battle of Poitiers in 1355, one of the most important early battles in the Hundred Years War. While Jean was imprisoned in the Tower of London, his eldest son, Charles, then seventeen years old, served as regent in his absence. History affords few more inspiring examples of chivalrous conduct than Jean’s after he gained his freedom by paying a steep ransom and—as was customary at the time—offering one of his sons, Louis of Anjou, as hostage: when Louis escaped, Jean was so troubled by what he saw as a dishonorable act that he returned, voluntarily and for the remainder of his life, to imprisonment in England (admittedly in the Savoy Palace), where he died in 1364. Thereupon Charles became king outright.

The Parisians had always been and would always be restive subjects of the crown. Even before Charles became king he found himself in the midst of a civil war that pitted the monarchy against Étienne Marcel (the provost of merchants and, in effect, the mayor of Paris), who sought to curb royal power and even, some said, to seize the crown itself. Only with Marcel’s assassination in 1358—soon after he burst into Charles’s council chamber in the Palais de la Cité and killed two of his advisors—did something like peace return, thanks in large part to Charles’s issuing a general amnesty that conciliated the nobles and the Parisian bourgeoisie. By the end of his reign, with Normandy and Brittany having been recaptured from the English some years before, Charles left the kingdom far stronger than when he had received it.

Despite the tumult of his early years, however, he seems to have preferred the vita contemplativa to the vita activa. In her Livre des fais et bonnes meurs du sage roy Charles V of 1404 (Book of the Deeds and Good Character of the Wise King Charles V), Christine de Pizan calls him “a true philosopher and lover of wisdom.” Surnamed le Sage, the Wise, he was renowned among his contemporaries for his manifold intellectual attainments. At his death, more than nine hundred volumes were inventoried in his library at the Louvre, a staggering number for that age. An additional three hundred were dispersed among his palaces in or near Paris. As one of his services of enlightenment, he lent books to scholars and to men of wealth who wished to commission a copy. His library, which included devotional works as well as volumes of political theory, history, astronomy and fiction, occupied three levels of the Tour de la Fauconnerie (the Falconry Tower), which he had built in the northwest corner of the Louvre when he turned the fortress into a palace. The most precious manuscripts were kept on the ground floor, while lighter fare, such as The Travels of Sir John Mandeville and Jean de Meun’s Roman de la rose (The Romance of the Rose), occupied the intermediary level. The highest level was reserved for learned and devotional works, in both French and Latin: among these were Guillaume Peyraut’s Livre du gouvernement des rois et des princes (Book of the Government of Kings and Princes), John of Salisbury’s Policraticus and Aristotle’s Economics, Politics and Nicomachean Ethics.10

Although these precious volumes were mostly dispersed after his death, a number of them found their way early on into the Bibliothèque nationale. Indeed, they may fairly be seen as the foundational tomes of the national library of France. In 1986, after preliminary excavations had been carried out for the Grand Louvre of François Mitterrand, one of the stones from the tower of Charles’s library came to light. In an extraordinary act of symbolism, it was taken across the Seine to the Left Bank, where it now forms the cornerstone of the new national library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

As much as Charles cherished the life of the mind, he shared with many potentates a love of great building projects, among these the Château de Vincennes at the eastern limit of modern Paris and the now vanished Hôtel Saint-Pol in the Marais. Writing of his love of architecture, Christine de Pizan described him as a “wise artist who showed himself to be a true architect, and confident deviser and prudent arranger . . . when he laid the beautiful foundations [of his buildings].”11 The largest of his undertakings was the construction of a new wall around the northern half of Paris, to encompass all those areas that had emerged since the completion of Philippe Auguste’s wall nearly two centuries before. This fortification, far more sophisticated in conception and construction than its predecessor, encircled only the right bank. And it too would have an incalculable effect on the fortunes of the Louvre.

If the earlier wall was three miles in total on both sides of the Seine, this new one, although confined to the Right Bank alone, had a longer circuit, embracing most of today’s First, Second, Third and Fourth Arrondissements. As such it extended roughly half a kilometer further to the east and to the west and one kilometer further to the north. In terms of urban development, the Left Bank would lag behind the Right for several centuries to come.

This wall of Charles V had been initiated, in fact, by Étienne Marcel in 1356, but was completed only in 1383, three years after Charles died, in the reign of his son Charles VI. Unlike the earlier wall, which rose directly out of the ground, Charles’s wall emerged from a broad and continuous earthwork whose sequence of crests and valleys, 280 feet wide, held the English at a sufficient distance that their arms could have no effect on the capital. Much later, these ramparts would come to be known as boulvars (cognate with the English word bulwark), from which is derived the modern English word boulevard. What connects these two seemingly disparate concepts is the fact that Paris’s grands boulevards—which technically refer only to the boulevards of the First through the Fourth Arrondissements—are the remains of Charles V’s fortifications. His bulwarks—together with those that were added to them by Louis XIII—were dismantled, flattened and filled in by Louis XIV starting around 1670, to be replaced by the sort of broad, landscaped avenues to which we now refer, wherever we find them in the world, as boulevards.

Interrupting the fourteenth-century bulwarks were grandiose gates through which pedestrians and riders passed into and out of the capital, among these the Porte Saint-Martin, the Porte Saint-Denis and an entirely new fortification all the way at the eastern end of the wall, known as la Bastille