6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

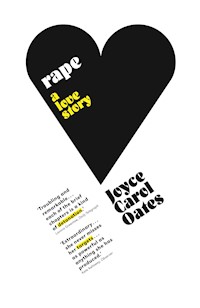

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Marijuana is the everyman drug. Teenagers surreptitiously toke on it, politicians refuse to inhale it, even your mum and dad have had a go. Marijuana is a mellow, let's put on a Barry Manilow CD, open a bottle of vino, and order a pizza drug. It's the easy drug. The no howling at the moon drug. No shooting up and losing your job.The Marijuana Chronicles presents 17 tales of the weird, wonderful and just plain stoned from some of the coolest most chilled out writers around. From drug busts to recipes, this is the stoner's definitive literary bible. Featuring brand-new stories by Joyce Carol Oates, Lee Child, Linda Yablonsky, Jonathan Santlofer, Thad Ziolkowski, Raymond Mungo, Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, Edward M. Gómez, Philip Spitzer, Dean Haspiel, Maggie Estep, Amanda Stern, Bob Holman, Rachel Shteir, Abraham Rodriguez, Jan Heller Levi, and Josh Gilbert. On the heels of The Speed Chronicles (Sherman Alexie, William T. Vollmann, Megan Abbott, James Franco, Beth Lisick, Tao Lin, etc.), The Cocaine Chronicles (Lee Child, Laura Lippman, etc.), and the The Heroin Chronicles (Eric Bogosian, Jerry Stahl, Lydia Lunch, etc.), comes The Marijuana Chronicles. Joyce Carol Oates, Lee Child, Linda Yablonsky, and other take short fiction to a higher level (though they don't inhale).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Featuring brand-new stories, poems, and graphics by:

Joyce Carol Oates, Lee Child, Linda Yablonsky, Thad Ziolkowski, Raymond Mungo, Cheryl Tan, Edward Madrid Gomez, Philip Spitzer, Dean Haspiel, Maggie Estep, Amanda Stern, Bob Holman, Abraham Rodriguez, Jan Heller Levi, and others.

THIS IS A COLLECTION, SCRAPBOOK, TRIBUTE (with possibly one or two condemnations)—call The Marijuana Chronicles what you will, it’s the book everyone will be talking about in between tokes. The literary gift for those hip college grads and doctoral students, your best friend and your best friend’s mother who went to Woodstock, the book you bring to those Wall Street dinner parties and East Village readings, a book that is long overdue. Like Dave Chappelle says: “Hey, hey, hey. Smoke weed every day.”

JERRY STAHL (Editor) is the author of five best-selling novels, The Death Artist, Color Blind, The Killing Art, Anatomy of Fear, and The Murder Notebook. He is the recipient of a Nero Wolfe Award, two National Endowment for the Arts grants, and has been a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome, the Vermont Studio Center, and serves on the board of Yaddo, the oldest arts community in the US. He is coeditor, contributor, and illustrator of the anthologies The Dark End of the Street and LA Noire: The Collected Stories. His short stories have appeared in several anthologies and magazines including The Rich & the Dead, New Jersey Noir, and Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. Also a well-known artist, Santlofer’s artwork is in such collections as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Newark Museum, Norton Simon Museum, and Tokyo’s Institute of Contemporary Art. He is currently completing a new novel. A native New Yorker, Santlofer lives and works in Manhattan.

ALSO IN THE AKASHIC DRUG CHRONICLES SERIES:

The Cocaine Chronicles edited by Gary Phillips & Jervey Tervalon

The Heroin Chronicles edited by Jerry Stahl

The Speed Chronicles edited by Joseph Mattson

Some of my finest hours have been spent on my back veranda, smoking hemp and observing as far as my eye can see. —Thomas Jefferson

I now have absolute proof that smoking even one marijuana cigarette is equal in brain damage to being on Bikini Island during an H-bomb blast. —Ronald Reagan

I didn’t inhale it, and never tried it again. —Bill Clinton

When I was a kid I inhaled frequently.That was the point. —Barack Obama

Forty million Americans smoked marijuana;the only ones who didn’t like it were Judge Ginsberg, Clarence Thomas, and Bill Clinton. —Jay Leno

I think that marijuana should not only be legal,I think it should be a cottage industry. —Stephen King

Researchers have discovered that chocolate produces some of the same reactions in the brain as marijuana. The researchers also discovered other similarities between the two but can’t remember what they are. —Matt Lauer

Hey, hey, hey, smoke weed every day. —Dave Chappelle

table of contents

Introduction

PART I: DANGEROUS

My First Drug Trial

Lee Child

High

Joyce Carol Oates

Jimmy O’Brien

Linda Yablonsky

The Last Toke

Jonathan Santlofer

PART II: DELIRIUM & HALLUCINATION

Moon Dust

Abraham Rodriguez

Cannibal Sativa

Dean Haspiel

Zombie Hookers of Hudson

Maggie Estep

Pasta Mon

Bob Holman

PART III: RECREATION & EDUCATION

Ganja Ghosts

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Acting Lessons

Amanda Stern

Ethics Class, 1971

Jan Heller Levi

The Devil Smokes Ganja

Josh Gilbert

No Smoking

Edward M. Gómez

PART IV: GOOD & BAD MEDICINE

Kush City

Raymond Mungo

Julie Falco Goes West

Rachel Shteir

Tips for the Pot-Smoking Traveler

Philip Spitzer

Jacked

Thad Ziolkowski

introduction smoke: seventeen writers on going to pot

by jonathan santlofer

P ot. Grass. Hemp. Hash. Herb. Reefer. Ganja. Smoke. Spliff. Weed. Kush. Mary Jane. Cannabis. Tea. Blunt. Dope. Doobie.

Marijuana. The popular drug. The newsworthy drug. The everyman and everywoman drug. Medical marijuana. Recreational pot. A drug for the young, the old, and everyone in between. The drug that doesn’t have you pawning the family silver along with your mother. The mellow—put on a Barry White CD, open a jug of vino, and send out for a dozen Dunkin’ Donuts—drug. The cool drug. The no howling at the moon (well, maybe not) drug.

Whatever you want to call it, marijuana, cannabis, and hemp have been around for a long time. As a food in ancient China, a textile in 4000 BC Turkestan, referred to as “Sacred Grass” in Hindu texts long before Christ. Scythian tribes left cannabis seeds as offerings to the gods. Herodotus wrote on its recreational and ritualistic use. There is evidence that the Romans used it medicinally and the Jewish Talmud touted its euphoric properties. Syrian mystics introduced it to twelfth-century Egypt, and Arabs traded it along the coast of Mozambique. Marco Polo reported on hashish in his thirteenth-century journeys. Angolan slaves planted it between rows of cane on Brazilian plantations, the French and British grew cannabis and hemp in their colonies. George Washington cultivated it at Mount Vernon, and Thomas Jefferson grew it at Monticello. Around 1840 cannabis-based medicines became available in the US—Le Club des Hashischins (the Hashish-Eaters Club) was all the rage in Paris, and Turkish smoking parlors were opening in America. (All according to “A Short History of Cannabis,” by Neil M. Montgomery, Pot Night, Channel 4 Television, March 4, 1995.)

As marijuana’s popularity grew, the British taxed it, Napoleon banned it, Turkey made it illegal, Greece cracked down. In 1930, the US government ceded control of illegal drugs to the Treasury Department and Harry J. Anslinger, a prohibitionist zealot, was named the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, a job he managed to hold until 1962. Anslinger waged war against marijuana with a nationwide campaign that linked pot smoking to insanity, and the San Francisco Examiner ran an editorial in 1923 supporting this belief:

Marihuana is a short cut to the insane asylum. Smoke marihuana cigarettes for a month and what was once your brain will be nothing but a storehouse of horrid specters.

Clearly crazier and nastier than the vast majority of pot smokers would ever be, Anslinger went even further with his testimony at a Senate hearing, creating an abhorrent racial bias in regard to the drug:

There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing, result from marijuana usage. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and any others.

Though New York’s mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, commis sioned an in-depth study of the effects of smoking marijuana, which contradicted Anslinger’s claims, it was condemned as unscientific and wholly disregarded by the crusading narcotics bureau chief.

Meanwhile, Reefer Madness, the full-length 1936 black-andwhite propaganda movie, touted the dangers of a “new drug menace which is destroying the youth of America in alarmingly increasing numbers,” that would ultimately cause “emotional disturbances … leading finally to acts of shocking violence … ending often in incurable insanity.” Personally, I found the film’s wild partying, sex, and even murder campy fun despite the pious preaching and bad acting. In the end, you just can’t spell out the dangers of neon with neon and not make your audience want to try it!

The “culture of marijuana” was born (or reborn) sometime in the 1960s on college campuses across the US as students rallied against the Vietnam War and smoked pot publically. By 1965, it is believed, approximately one million Americans had tried the drug and within a few years that number had reached more than twenty million.

Nixon, Anslinger’s heir apparent, tried to crush it with “Operation Intercept,” an attempt to shut down border crossings between Mexico and the United States, while he raised the criminal stakes on marijuana possession so that a twenty-five-year-old Vietnam vet, Don Crowe, could be sentenced to fifty years in jail for selling less than an ounce. Though the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse released a 1972 study urging the decriminalization of smoking pot in the privacy of one’s own home, Nixon disregarded it, created the DEA, gave it the authority to enter houses “without knocking,” and began extensive wiretapping and intelligence-gathering on private citizens. The Reagan administration continued the war on drugs—who can forget first lady Nancy Reagan’s famous “Just Say No” campaign?

With the leap from “just say no” to the astonishing decriminalization of recreational pot by Colorado and Washington in 2012, one can now say the actual seeds of change have been sown. Eighteen states plus Washington, DC have now legalized medical marijuana, and a host of medical literature points to evidence that the drug, in its myriad forms, can be used in the treatment of nausea and vomiting, anorexia and weight loss, spasticity, neurogenic pain, movement disorders, asthma, glaucoma, epilepsy, bipoloar disorder, and Tourette’s syndrome. Recent studies with cannabis and cannabinoids show promise in treating arterial blockage, Alzheimer’s disease, autoimmune diseases, and blood pressure disorders. The FDA acknowledges that “there has been considerable interest in its use for the treatment of a number of conditions, including glaucoma, AIDS wasting, neuropathic pain, treatment of spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis, and chemotherapy-induced nausea,” but the agency has yet to approve it.

As Colorado governor John Hickenlooper points out, “Federal law still says marijuana is an illegal drug, so don’t break out the Cheetos or Goldfish too quickly.” While Colorado and Washington have made it legal to smoke, sell, or carry up to one ounce of marijuana, it will take some time to sort out the federal-versusstate issue. Despite the fact that there was no big funding in opposition to the legalization propositions—and despite a recent poll showing that “fifty percent of voters around the country now favor legalizing the drug for recreational use,” cited by Benjamin Wallace-Wells in the December 3, 2012 issue of New York—the battle is hardly over.

With the marijuana debate, medical or otherwise, ongoing and persistent, I knew I wanted to echo that in this anthology with the inclusion of some writing about the facts. So The Marijuana Chronicles includes both fiction and nonfiction pieces. The writer and journalist Rachel Shteir supplied just that in a story about can nabis advocate and multiple sclerosis sufferer Julie Falco, whose brave fight for survival is at once human and legal. The issue raises its head again in former student radical Raymond Mungo’s close-to-home tangled tale of the pursuit of legal and not-so-legal medical marijuana in California. The fact that the subject was taken up yet again but in an entirely fictional way in Thad Ziolkowski’s short story about a medical marijuana farm felt not only like kismet but a reflection of the zeitgeist and confirmation that art and life always share a stage.

Hollywood has long reflected and embraced the change in attitude with such stoner star turns as Cheech and Chong’s Up in Smoke, Sean Penn’s hilarious Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Jane Fonda’s pot-smoking hooker in Klute, Bridget Fonda in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, and the granddaddy of all counterculture stoner films, Easy Rider, wherein Peter Fonda (what is it with these Fondas?) introduces Jack Nicholson to his first smoke (and if you believe that was really Jack’s first toke, you will believe anything). Diane Keaton needed a hit to relax her in Annie Hall, and Jeff Bridges played the ultimate stoner dude in The Big Lebowski.

Like film, literature has been no stranger to the drug, going back to Charles Baudelaire’s 1860 Artificial Paradises, in which the French poet not only describes the effects of hashish but postulates it could be an aid in creating an ideal world. The pleasures, pains, and complexities of marijuana are more than hinted at in works by William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Henry Miller, Hunter S. Thompson, and Thomas Pynchon, to name just a few, and I hope this anthology will add to that legacy and keep the flame of pot literature burning bright.

National Book Award winner Joyce Carol Oates creates an instant classic for the genre in her dark tale of suburban-meetsurban weed consumption gone wrong, and Linda Yablonsky turns your head inside out with a pot-smoking, cross-dressing, gun-toting character as alluring as he is terrifying.

I never expected pothead zombies but that’s just what Maggie Estep delivers in her zany and hilarious story. Cultural critic Edward M. Gómez gives us an urban tale at once real and idyllic, while Josh Gilbert takes us on a stoned journey through Hollywood hell. Amanda Stern offers us a coming-of-age cautionary tale with heart, soul, pot, and coke! And multi–award winning crime fiction author Lee Child could not help but write a story that will keep you guessing till the last line.

Marijuana crosses the ocean in Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan’s story of pot-smoking friends in Singapore, and Abraham Rodriguez rocks us back to the future with his idiosyncratic blend of sci-fi and urban realism.

Bob Holman and Jan Heller Levi produce poems filled with poignancy and humor which remind us that poetry and pot have had a long acquaintance, while award-winning graphic artist Dean Haspiel creates a hallucinogenic world in pictures. As for me, I won’t say how much of my story is real or imagined, but I do have a faded photo of my flower-painted face, which can be had for a price.

This diverse group of writers, poets, and artists makes it clear that there is no one point of view here. Each of them approaches the idea of marijuana with the sharp eye of an observer, anthropologist, and artist, and expands upon it. Some writing projects are difficult; this one was smooth and mellow and a continual pleasure.

As a survivor of the sex-and-drug revolution, I could never have imagined the decriminalization of my generation’s forbidden fruit. Perhaps there is another Anslinger waiting in the wings, but practically every day a new article extols the virtues of medical marijuana and other states get ready to put the drug in the category of alcohol. Is it possible that in a few years it will be easier to buy a pack of joints than cigarettes? I don’t know the answer to that but in the meantime I hope you will sit back, relax, and enjoy these wide-ranging tales of the most debated and discussed drug of our time. Though, according to former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, “That is not a drug, it’s a leaf.”

Jonathan Santlofer

New York City

April 2013

PART I

DANGEROUS

LEE CHILD has been a television director, union organizer, theater technician, and law student. He is the author of the Jack Reacher novels. He was born in England but now lives in New York City and leaves the island of Manhattan only when required to by forces beyond his control. Visit www.leechild.com for more information on his books, short stories, and the Jack Reacher movie starring Tom Cruise.

my first drug trial

by lee child

W as it smart to smoke a bowl before heading to court? Probably not. The charge was possession of a major quantity, and first impressions count, and a courtroom is a theater with all eyes on just two main characters: the judge, obviously, but mostly the accused. So was it smart?

Probably not.

But what choice did I have? Obviously I had smoked a bowl the night before. A big bowl, to be honest. Because I was nervous. I wouldn’t have slept without it. Not that I have tried to sleep without it, even one night in twenty years. So that hit was routine. I slept the sleep of the deeply stoned and woke up feeling normal. And looking and acting normal, I’m sure. At breakfast my wife made no adverse comment, except, “Use some Visine, honey.” But it was said with no real concern. Like advice about which tie to choose. Which I was happy to have. It was a big day for me, obviously.

So I shaved and dripped the drops into my eyes, and then I showered, which on that day I found especially symbolic. Even transformational. I felt like I was hosing a waxy residue that only I could see out of my hair and off my skin. It sluiced away down the drain and left me feeling fresh and clean. A new man, again. An innocent man. I stood in the warm stream for an extra minute and for the millionth time half-decided to quit. Grass is not addictive. No physical component. All within my power. And I knew I should.

That feeling lasted until I had finished combing my hair. The light in my bathroom looked cold and dull. The plain old day bore down on me. Problem is, when you’ve stayed at the Ritz, you don’t want to go back to the Holiday Inn.

I had an hour to spare. Courts never start early. I had set the time aside to review some issues. You can’t expect lawyers to spot everything. A man has to take responsibility. So I went to my study. There was a pipe on the desk. It was mostly blackened, but there were some unburned crumbs.

I opened the first file. They had given me copies of everything, of course. All the discovery materials. All the pleadings and the depositions and the witnesses. I was familiar with the facts, naturally. And objectively, they didn’t look good. Any blow-dried TV analyst would sit there and say, Things don’t look good here for the accused. But there were possibilities. Somewhere. There had to be. How many things go exactly to plan?

The unburned crumbs were fat and round. There was a lighter in the drawer. I knew that. A yellow plastic thing from a gas station. I couldn’t concentrate. Not properly. Not in the way I needed to. I needed that special elevated state I knew so well. And it was within easy reach.

Irresponsible, to be high at my first drug trial.

Irresponsible, to prepare while I was feeling less than my best.

Right?

I held the crumbs in with my pinkie fingernail and knocked some ash out around it. I thumbed the lighter. The smoke tasted dry and stale. I held it in, and waited, and waited, and then the buzz was there. Just microscopically. I felt the tiny thrills, in my chest first, near my lungs. I felt each cell in my body flutter and swell. I felt the light brighten and I felt my head clear.

Unburned crumbs. Nothing should be wasted. That would be criminal.

The blow-dried analysts would say the weakness in the prosecution’s case was the lab report on the substances seized. But weakness was a relative word. They would be expecting a conviction.

They would say the weakness in the defense’s case was all of it.

No point in reading more.

It was a railroad, straight and true.

Nothing to do for the balance of the morning hour.

I put the pipe back on the desk. There were paperclips in a drawer. Behind me on a shelf was a china jar marked Stash. My brother had bought it for me. Irony, I suppose. In it was a baggie full of Long Island grass. Grown from seeds out of Amsterdam, in an abandoned potato field close enough to a bunch of Hamptons mansions to deter police helicopters. Rich guys don’t like noise, unless they’re making it.

I took a paperclip from the drawer and unbent it and used it to clean the bowl. Just housekeeping at that point. Like loading the dishwasher. You have to keep on top of the small tasks. I made a tiny conical heap of ash and carbon on a tissue, and then I balled up the tissue and dropped it in the trash basket. I blew through the pipe, hard, like a pygmy warrior in the jungle. Final powdered fragments came out, and floated, and settled.

Clean.

Ready to go.

For later, of course. Because right then those old unburned crumbs were doing their job. I was an inch off the ground, feeling pretty good. For the moment. In an hour I would be sliding back to earth. Good timing. I would be clear of eye and straight of back, ready for whatever the day threw at me.

But it was going to be a long day. No doubt about that. A long, hard, pressured, unaided, uncompensated day. And there was nothing I could do about it. Not even I was dumb enough to show up at a possession trial with a baggie in my pocket. Not that there was anywhere to smoke anymore. Not in a public facility. All part of the collapse of society. No goodwill, no convenience. No joy.

I swiveled my chair and scooted toward the shelf with the jar. Just for a look. Like a promise to myself that the Ritz would be waiting for me after the day in the Holiday Inn. I took off the lid and pulled out the baggie and shook it uncrumpled. Dull green, shading brown, dry and slightly crisp. Ready for instantaneous combustion. A harsher taste that way, in my experience, but faster delivery. And time was going to count.

I decided to load the pipe there and then. So it would be ready for later. No delay. In the door, spark the lighter, relief. Timing was everything. I crumbled the bud and packed the bowl and tamped it down. I put it on the desk and licked my fingers.

Timing was everything. Granted, I shouldn’t be high in court. Understood. Although how would people tell? I wasn’t going to have much of a role. Not on the first day, anyway. They would all look at me from time to time, but that was all. But it was better to play it safe, agreed. But it was the gap I was worried about. The unburned crumbs were going to give it up long before I arrived downtown. Which was inefficient. Who wants twenty more minutes of misery than strictly necessary?

I picked up the lighter. No one in the world knows more than I do about how a good bud burns. The flame licks over the top layer, and it browns and blackens, and you breathe right in and hold, hold, hold, and the bud goes out again, and you hold some more, and you breathe out, and the hit is there. And you’ve still got ninety percent left in the bowl, untouched, just lightly seasoned. Maybe ninety-five percent. Hardly like smoking at all. Just one pass with the lighter. Merely a gesture.

And without that gesture, twenty more minutes of misery than strictly necessary.

What’s a man supposed to do?

I sparked the lighter. I made the pass. I held the smoke deep inside, harsh and hot and comforting.

My wife came in.

“Jesus,” she said. “Today of all days?”

So it was her fault, really. I breathed out too soon. I didn’t get full value. I said, “No big deal.”

“You’re an addict.”

“It’s not addictive.”

“Emotionally,” she said. “Psychologically.”

Which was a woman thing, I supposed. A man has a stone in his shoe, he takes it out, right? Who walks around all day with a stone in his shoe? I said, “Nothing’s going to happen for an hour or so.”

She said, “You can’t afford to fall asleep. You can’t afford to look all spacey. You understand that, right? Please tell me you understand that.”

“It was nothing,” I said.

“There will be consequences,” she said. “We’re doing well right now. We can’t afford to lose it all.”

“I agree, we’re doing well. We’ve always done well. So don’t worry.”

“Today of all days,” she said again.

“It was nothing,” I said again. I held out the pipe. “Take a look.”

She took a look. Exactly as predicted. The top layer a little burned, the rest untouched but lightly seasoned. Ninety-five percent still there. A breath of fresh air. Hardly like smoking at all.

She said, “No more, okay?”

Which I absolutely would have adhered to, except she had made me waste the first precious moment. And I wanted to time it right. That was all. No more and no less. I wanted to be ready when the fat guy in the uniform called out, All rise! But not before. No point in being ready before. No point at all.

My wife spent a hard minute looking at me, and then she left the room again. The car service was due in about twenty minutes. The ride downtown would take another twenty. Plus another twenty milling around before we all got down to business. Total of an hour. The aborted breath would have seen me through. I was sure of that. So one more would replace it. Maybe a slightly smaller version, to account for the brief passage of time. Or maybe a slightly larger version, to compensate for the brief upset. I had been knocked off my stride. Ritual is important, and interference can be disproportionately destructive.

I sparked up again. The yellow lighter. A yellow flame, hot and pure and steady. Problem is, the second pass burns better. As if those lower seasoned layers are ready and waiting. They know their fate, and they’re instantly ready to cooperate. Smoke came up in a cloud, and I had to breathe in hard to capture all of it. And second time around the bud doesn’t extinguish quite so fast. It keeps on smoldering, so a second breath is necessary. Waste not, want not.

Then a third breath.

By which time I knew I was right. I was getting through the morning just fine. I had saved the day. No danger of getting sleepy. I wasn’t going to look spacey. I was bright, alert, buzzing, seeing things for what they were, open to everything, magical.

I took a fourth breath, which involved the lighter again. The smoke was gray and thick and instantly satisfying. I could feel the roots of my hair growing. The follicles were thrashing with microscopic activity. I could hear my neighbors getting ready for work. Stark and absolute clarity everywhere. My spine felt like steel, warm and straight and unbending, with brain commands rushing up and down its mysterious tubular interior, fast, precise, logical, targeted.

I was functioning.