18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

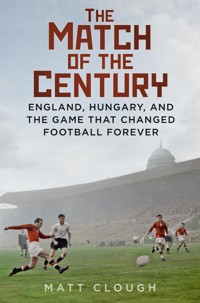

On 25 November 1953, the footballing landscape was altered forever. In a mist-shrouded Wembley Stadium, the beautiful game's historic dominant force, England, met the most exciting team of the 1950s, Hungary. What followed sent shockwaves through the very foundations that the sport was built upon. After years of crumbling decline, the British Empire seemed to be enjoying a resurgence with the coronation of the popular young Elizabeth II. As such, England played with the crushing weight of expectation upon their shoulders, defending their proud, unbeaten home record and protecting the reputation of the nation. Hungary, meanwhile, took on football's most venerated team in the knowledge that they had the opportunity to make history by emerging victorious – anything less would not be tolerated. The newspapers called it the Match of the Century before it had even begun. By the time it was over, writers, players and fans were wondering if such a lofty billing had in fact undersold the contest. Now, over sixty years later, the match is imbued with meaning and symbolism far beyond the football pitch. This is the story of a match that would change the course of football history forever.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Matt Clough, 2022

The right of Matt Clough to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9227 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

1 The Engineer and the Count

2 The Old Masters

3 Pomp and Circumstance

4 The Young Pretenders

5 Thinking the Unthinkable

6 Mr Sebes, It’s Time We Arranged a Match

7 Island Supremacy

8 Brave New World

9 Uncorking the Stopper

10 The Silence Before the Storm

11 The Match of the Century

12 The Twilight of the Gods

13 Goodbye, England!

Notes

Bibliography

1

THE ENGINEER AND THE COUNT

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

William Faulkner

Spanning the glittering, aquamarine waters of the Danube, in the shadow of the imposing Hungarian Parliament in the beating heart of Budapest, there stands a bridge. Amid the Hungarian capital’s architectural splendour, the Széchenyi Chain Bridge stands alone in its alchemy between form and function. Not only a connection between the ancient conurbations of Buda and Pest either side of the Danube, the Chain Bridge, flanked at either end by a pair of formidable stone lions, is a work of art. It owes its almost two centuries of existence principally to two men.

In many respects, William Tierney Clark and Count István Széchenyi were unlikely bedfellows, sharing little aside from a relatively close proximity in age. Clark, from Bristol, lost his father early in childhood and by the age of 12 was apprenticed to a millwright so he could learn a trade and begin providing for his family. Through hard work and some star-crossed meetings, Clark found himself rising swiftly through the ranks at West Middlesex Water Works.

In eras past, the destiny for those like Clark, forced from education in order to provide, was generally a life of drudgery, of little ambition beyond scrabbling to make ends meet. However, he was the personification of the rising tide of industrial prowess sweeping Britain in the early to mid-nineteenth century. After centuries of a strict class system, the promise of the Industrial Revolution went some way to finally breaking down barriers. Britain needed innovators and brilliant minds to help push boundaries, and quickly found that the lower classes were every bit as likely to produce them as the upper classes were. It was a time of nearly unprecedented opportunity in Britain’s history to that point, and men like Clark were the chief beneficiaries.

Before long, his brilliant mechanical mind was focused upon the singular problem with which he would make his name – bridges. His crowning achievement in Britain was Hammersmith Suspension Bridge, the first suspension bridge to span the Thames, which melded engineering brilliance with artistic flair, thanks to a neoclassical design. This meeting of style and substance was typical of many of the Industrial Revolution’s greatest achievements and, combined with the vast news-spreading capabilities of the British Empire, played a critical role in making Britain not only the workshop of the world, but the envy of much of it too.

By the completion of Hammersmith Bridge, Clark’s appearance was replete with many of the features that have come to be associated with his time. Typically clad in black, he boasted bristling sideburns that helped bring some volume to an otherwise sallow, almost sickly face that was well accustomed to an austere expression.

Széchenyi, who arrived in Britain in 1832 on a fact-finding mission, hoping to learn all he could from Britain’s sudden explosion of industrial vigour, did not possess such an unassuming appearance. A receding hairline of jet-black hair was accompanied by a chinstrap beard that brought to mind a Jacobian ruff. An impressive moustache sat atop his lip. Remarkably, none of these features were his most notable; that accolade went to a pair of mesmerically thick eyebrows which lent him an air of sombre wisdom.

It was a striking appearance that befitted a striking man. Born into enormous wealth and privilege, Széchenyi, the youngest of five children, could have easily lived out his life in opulent indolence. Instead, he joined the army at 17 and conducted himself with distinction during the Napoleonic Wars before travelling through Europe to glean insights into how he could help to modernise and improve life in his homeland of Hungary. He would ultimately be instrumental in the introduction of everything from critical railway infrastructure and steam navigation to milling and even horse racing.

He was fanatical about bringing British innovations home, but few stoked his imagination as Clark’s Hammersmith Bridge did. Széchenyi rhapsodised that the bridge was far more than just a solution to a problem; it was, in fact, a creation of ‘astounding appearance’, a construction with the capability to ‘overwhelm the senses, and to deprive man of his judgement’. 1 At the time, the vast River Danube rolled between two cities, Buda and Pest, and no permanent structure connected the two metropolises. Gazing upon Clark’s structure across the Thames, Széchenyi knew he had found the solution for spanning the river and laying the foundations for modern-day Budapest.

Széchenyi and Clark began liaising frequently and before long a plot was hatched. Széchenyi set about persuading the Hungarian Parliament of the project’s merits, while Clark busied himself with designing his masterpiece. After years of carefully navigating bureaucratic channels more treacherous than the ice flows that drifted down the Danube in winter, ground was finally broken in 1840, and the bridge opened nine years later. Appropriately for such a grand tour de force, the final stages of the bridge’s construction coincided with a tumultuous epoch in Hungary’s history, as they fought for independence from Austria and the Habsburg Empire. At several points, the almost-finished bridge was threatened, never more so than when Austrian troops attempted to destroy it in order to halt the advancing Hungarian forces, only for the officer charged with demolishing the bridge to accidentally use the explosives on himself. The survival and completion of the bridge, denoting as it did a huge symbolic step towards modernity for Hungary, served as an apt metaphor for the revolution. Though the Hungarians were eventually defeated, the groundwork had been laid for the spirit of Hungarian nationalism which would play a critical role in the country’s future.

The Széchenyi Chain Bridge remains as a timeless reminder of the relationship between Hungary and Britain – and a core difference between the national characters of the two nations. For Hungary, there was no shame at all in seeking help from others in order to advance their personal cause; gleaning advice from outside could help to avoid long and often painful learning curves. At the same time, as the British Empire’s diaspora was spreading the gospel of Britain and her innumerable innovations far and wide, a more insidious aspect was being ingrained within the national psyche at home: a stubbornness, an assumption of unending supremacy, an arrogance that lent itself to an unwillingness to learn from elsewhere. The British Empire was unrivalled in expanse and power – what could anyone else possibly have to offer it?

Half a century after the completion of the Chain Bridge, another cultural exchange between the two nations was taking place. The glamour of the British Empire’s unfettered power had translated to a rampant strain of Anglomania across Austria and Hungary, where the well-to-do equated British fashion, art and culture with status. This trend was so prevalent that even British exports considered working class and gauche at home were elevated and given a rarefied air by the time they reached Budapest or Vienna.

This was the case when an exciting new ball game named football arrived, close to the turn of the twentieth century. The game had its theoretical origins in the minds and quadrangles of Cambridge and Oxford but was given physical life in the muddy quagmires and on the begrimed cobbles of the north of England and Scotland. By the time football was being exported elsewhere, the British upper classes were already turning their backs on it.

The British elites deemed football’s simplicity, and the resulting fervid adoption of the game across the working-class strongholds within northern England and Scotland (the traditional Saturday 3 p.m. kick-off time was codified in response to the time factories let out, giving the workers enough time to make it to the grounds), as reasons to denigrate and dismiss football. By the time word of the game reached the coffee shops on the banks of the Danube, the class distinction had been diluted and lost and the Hungarian establishment and proletariat alike were swiftly in thrall to the new sport.

The very act of exporting the game, and the biases that were lost along the way, triggered the first rift between the British and Hungarian versions of football. In Britain, the game, associated with the mill towns and mines of places like Manchester, Bolton, Newcastle and Sunderland, was arrogantly assumed to be of no intellectual merit, and anyone who disagreed was treated with suspicion or outright hostility. In Hungary, it was viewed with the same respect as a piece of high culture and was regarded with intellectual rigour. The same men who, in Britain, were mocked for believing there could be more to the game than the fundamentals, were welcomed to countries like Hungary with a sort of hushed reverence, their words and ideas pored over like religious manuscripts or ground-breaking literature. This intellectual esteem for the sport would remain fundamental to generations of Hungarian football players, coaches and fans.

Men like Clark had been born at a unique point in Britain’s modern history when the gifted could rise to the top, regardless of status or circumstance, but by the time football emerged, the Industrial Revolution was emitting its dying embers, and with it the possibility of upward movement was being replaced by a return to a more stratified society of haves and have-nots. Though it would take decades to coalesce, it was this shift, this closing off of opportunity, this attempt by those already satisfied with their lot to lift up the drawbridge behind them to prevent others from crossing it, that would play a critical role in the eventual decline and collapse of the British Empire. The same insidious pattern would be mirrored across the board rooms and training pitches of football clubs across England, as well as in the corridors of power in the Football Association’s (FA) headquarters at Lancaster Gate.

The Chain Bridge was partially destroyed during the catastrophic, bloody siege of Nazi-occupied Budapest by the Soviet Red Army during the Second World War, before being rebuilt and reopened in 1949 to stand once again as a testament to Hungary’s strength and resilience, its willingness to learn, and a commitment to pragmatism mixed with aesthetics. At the same moment, the exact same qualities could be found in the country’s remarkable national football team, a team that synthesised a mechanically engineered, almost forensic approach to the science of football with an effervescent, joyous beauty in a manner never before seen on a football pitch. Over the following years, despite enormous pressure and political strife, the team would conquer all before them, before being granted an irresistible opportunity to prove themselves in the ultimate way. In November 1953, the Hungarian team emerged from behind the Iron Curtain and took up the mantle of attempting to become the first team from beyond the British Isles to defeat England on their home soil.

In their way stood an England team that, like Britain during the post-war disintegration of the empire, was facing a reckoning. Their proud, undefeated home record remained the hook upon which all expectations, all esteem and all assumptions of supremacy were hung. The pool of players the FA had to pick from was formidable – league winners, cup heroes, two future England record goal scorers, another who would become the first to reach 100 caps for his country, and arguably the most famous player on the planet. Yet, after finally bowing to the global tide and expanding their horizons beyond a narrow obsession with the home nations, the venerated status of the England national team was under threat like never before, particularly following a disastrous maiden World Cup.

Once the afterglow of the Allied victory in the Second World War had waned and the triumphant street party bunting had been taken down, Britain had been left to survey a scene of utter devastation: nearly half a million dead, cities levelled by the Luftwaffe, an economy propped up by American aid (an unthinkable prospect just years before), rationing not only still in effect but more stringent than during the war itself. The empire was crumbling. India had achieved independence in 1947 and was shortly followed by Ceylon and Brunei, while other colonies and dominions laid the groundwork for eventual independence. Though it would take the Suez Crisis in 1956 to truly underline just how diminished Britain’s standing in the new world order was, there was no question that the empire was faltering badly. At a time when the English people were looking to their football team more than ever as a beacon of hope and an affirmation of Britain’s status despite mounting evidence to the contrary, the pressure upon the players had never been greater.

* * *

The day of 25 November 1953 dawned with a scene that could just as easily have belonged to the Victorian London of Arthur Conan Doyle or Robert Louis Stevenson as it did the post-war era. Heavy overnight rain had left the streets slick and glassy, upon which ghostly apparitions of the buildings towering above them were reflected. The rain had given way to a cloying, nearly impenetrable fog against which the gas-lit street lamps strained. Cars rolled steadily past commuters swaddled in overcoats, hunched against the cool autumn air. Less than ten years before the Beatles inaugurated a decade of psychedelic technicolour, this was England in sepia, in many respects unchanged from the early 1900s.

Maintaining the status quo was precisely what the England team sought to achieve that day. Teams had arrived from the Continent amid great fanfare before, and the Three Lions had always thwarted their ambitions. It was imperative that they did so once again.

Excitement and anticipation was at fever pitch as the teams walked out onto the famous Wembley Stadium pitch for what the newspapers were calling ‘The Match of the Century’. West versus East, capitalism versus communism, the masters versus the students, the old guard versus the upstarts, the British Empire versus a satellite of the Soviet Union, tactical stagnation versus innovation, Stanley Matthews, Billy Wright and Alf Ramsey versus Ferenc Puskás, Sándor Kocsis and Nándor Hidegkuti. It all rested on the outcome of England versus Hungary. All that remained for them to do was play.

2

THE OLD MASTERS

The story of Britain in the first half of the twentieth century is one of tumult and upheaval. The nation entered the 1900s with an unprecedented expanse of empire, a rich cultural reputation and a renown as the workshop of the world. It wasn’t simply goods that the empire exported around the globe, but ideas and inventions. Victorian-era Britain had given the world the telephone, the rubber tyre, the modern form of the postal service and thousands of other innovations that had greased the wheels of commerce to an unprecedented slickness.

In 1900, there was no reason to suspect that anything on the horizon could challenge Britain’s pre-eminent position, aside from the fear that the empire had grown so vast that defending it all could stretch resources to breaking point, even as the nation allocated more than half of all public spending to imperial defence. 1 Queen Victoria remained on the throne, demand from other nations for British coal and textiles continued to boom as other countries desperately attempted to keep up with the unassuming little island in the north Atlantic, and Britain continued to produce brilliant individuals, capable of keeping foreign theatres packed to the rafters, their readers enraptured and their factories firing.

One British invention, codified in 1868 after a glacial formation over centuries (as far back as the 1300s, Edward III had been moved to ban it in order to have his subjects focus on archery to aid Britain’s cause in the Hundred Years War), 2 was less trumpeted, at least by the upper-middle and upper classes who tended to act as gatekeepers for what was and wasn’t exported across the empire. By the 1900s and 1910s, however, this particular creation could not be stopped by any border, natural, political or otherwise, nor could it be held back by those who deemed it a pursuit of low worth and questionable moral value.

It may have taken hundreds of years to reach the point where the English Football Association formalised it and twelve trail-blazing clubs organised the first coordinated league season (in 1888), but from then on, association football spread like a virus, a sporting epidemic that took root in any host it could, hopping from person to person, port to port, field to field, until it had enveloped the globe. This proliferation was charged by the sport’s accessibility (anything could be – and invariably was – scrunched up and substituted for a ball) and its deceptive simplicity, which masked endless complexities, combinations and possibilities.

Within a matter of decades, football in Britain went beyond what any sport had previously achieved in terms of popularity and devotion. In the words of esteemed writer Arthur Hopcraft, football had become:

… not just a sport people take to, like cricket or tennis or running long distances. It is inherent in the people. It is built into the urban psyche, as much a common experience to our children as are uncles and school. It is not a phenomenon; it is an everyday matter. 3

The effect was mirrored across the globe. From Liverpool to Lisbon, Cambridge to Calcutta, Bolton to Belo Horizonte, Blackburn to Budapest, football fanned out like wildfire.

Nowhere was impervious. The game’s most fervent apostles in the first decades of the twentieth century were British soldiers, stationed in every far-flung outpost of the empire, which by 1910 included New Zealand, numerous Caribbean and Pacific islands, Nigeria, British Guyana and, of course, India. Even in the fleeting moments of calm amid hails of gunfire, billowing acrid smoke and the stench of death, thoughts quickly turned to football, most famously in no man’s land on the Western Front at Christmas 1914, when a brief halt in the unfathomable carnage of the First World War saw British and German soldiers seize the opportunity to play impromptu matches.

These brief minutes of levity between warring soldiers were far from the first examples of football between nations, standing in as a proxy for far more serious disputes. Almost as soon as the rules of association football had been codified, the prospect of international matches had been raised. England took on Scotland in the first international in 1872, watched by 4,000, which ended 0-0 despite England fielding seven forwards and Scotland five. For the next three decades, England’s international schedule would remain entirely within the confines of the British Isles but would expand in frequency with the advent of the Home Championship, which began in 1883 and crowned a winner annually.

It wasn’t long, however, before this isolation began to chafe. By 1907, England had won the Home Championship on fourteen occasions, Scotland had won eleven and Wales one. A general lack of competitiveness and the repetition of England playing the same three teams meant that interest was stagnating, with home crowds rarely exceeding 30,000, a number that had barely moved since the mid-1890s. The time had come for England to cast her net further.

In 1908, the national team embarked on their first ever foreign tour, playing Austria (twice), Hungary and Bohemia, all then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. News of the Danubian fervour for football had reached British shores and inspired England’s choice for their first ever non-British opponents. However, all three opponents would swiftly come to understand that enthusiasm alone was not enough to earn parity with England’s team of full-time professionals. Over the course of the four games, England earned an aggregate victory of 28-2.

England’s early forays abroad were more important for their role in spreading the gospel of the sport rather than as sporting encounters. Though the games were of great interest abroad, at home they were regarded far more coolly, oddities that, from a competitiveness perspective, offered far less than a match with the Scottish did. Almost subconsciously, the England national team began to take on the same aura of benevolent superiority that had been used to justify Britain’s imperial expansion, the idea that those nations and their people, who had been subsumed and subjugated, no matter how brutally, were far better off with the British example than left to their own devices.

The tours also fired the imaginations of a new type of British traveller. Missionaries had been criss-crossing the globe in the name of countless causes and creeds for centuries, and the British Empire was no stranger to their likes. Some were well meaning (if misguided), attempting to teach the world the story of Christianity and what they felt was the only route to salvation. Others were less altruistic. The religious dogmatism of some was transmuted into racial and eugenical theories that, in turn, lent credence to some of the worst atrocities to occur in the name of the British Empire, with infamous figures such as Cecil Rhodes acting with ruthless impunity in the belief that the accident of their British birth gave them an inherent precedence.

It was with a far more benign mission that men began to set sail from British shores in the early 1900s to help spread the gospel of football. In the words of Rory Smith, these were the men ‘who taught the world how to beat England at their own game’. 4 William Garbutt, a former player, graduated from working on the Genovese docks to eventually become the godfather of Italian football management. Jack Greenwell, a miner from County Durham, travelled to Barcelona, first to play for the club and then manage them, eventually establishing them as one of the great forces of Spanish football. Jimmy Hogan, another former pro, travelled through Europe, planting seeds in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria and Hungary.

Even with these philanthropic figures exporting the British standard of tactical organisation and coaching, it would take until the late 1920s for Continental European nations to begin to catch England. In 1923, England failed to beat a Continental team for the first time, being held 2-2 by Belgium. Six years later, in Madrid, England finally lost their unbeaten record against mainland European teams, going down 4-3 to a spirited Spain. The Athletic News commemorated the occasion with a front-page headline announcing ‘England’s First Fall’, but set the tone for future coverage of England’s defeats to foreign opposition by focusing on mitigating factors (in this case, the long domestic season and the intense Spanish heat).

Just as it appeared that a truly competitive international landscape was emerging, the decades-long head start enjoyed by the home nations finally expended, the British FA took a fateful decision. The first World Cup was due to be played in Uruguay in 1930, but the British teams wouldn’t be there, having withdrawn from FIFA, first in 1919, then more permanently in 1928, ostensibly in an argument over the precise parameters of amateurism in the game. A more cynical interpretation of the timing of events is that England and their British neighbours, rather than countenance the idea that they might no longer sweep all comers aside, simply picked up their ball and went home. It would take the best part of twenty years before they returned to the fold. In the meantime, the home nations enjoyed a splendid isolation which allowed England to pick and choose their opponents and carefully cultivate their continuing claim of supremacy.

It wasn’t just on the football pitch that, after leading the way for so long, Britain suddenly appeared to be retreating. Victory in the First World War had come at a grave cost. Hundreds of thousands of British men had perished in unimaginable conditions. Those who gave the orders to send wave after wave of men out of their trenches into a hail of machine-gun bullets and certain death were typically upper class, cloistered behind miles of barbed wire and blissfully unaware of both the futility of their orders and the bloody carnage they were responsible for. Huge swathes of those who died hailed from Ireland, India and elsewhere in the empire. Those who returned home to tell their tales did so with renewed determination that they be afforded the right to self-governance and freedom from the yoke of Britain’s oppressive rule in exchange for their sacrifice.

The war also came with tremendous economic ramifications. Even as the Treaty of Versailles awarded Britain yet more territory, marking the high-water point of the empire’s expanse with rule over a quarter of the people on Earth, the hiatus in Britain’s global export business had ended its reign as the workshop of the world and seen nations such as the USA and Japan amass huge naval power. Before the war, David Lloyd George had pondered if the economic comforts afforded by the empire had bred complacency, a nation of ‘footballers, stock exchangers, public-house and music-hall frequenters’. 5 The rapidity of the empire’s decline following the war seemed to confirm the Welshman’s thesis.

The obstinacy of the officer class, when faced with irrefutable, bloody evidence that their modes and methods were woefully outdated, was to become a leitmotif of imperial thinking. This stubbornness pervaded everything from British attitudes to the people they ruled over, even as they became increasingly restless, to the loss of economic supremacy in staple industries such as textiles following the war. Many in Britain, from the leaders in Parliament, to the newspapermen, to the man on the street, simply wouldn’t countenance the idea that the sun could be setting on the British Empire. The same thinking was prevalent at the FA’s Lancaster Gate headquarters in their attitudes towards the national team, for which they refused to hire a manager, preferring instead to pick the team by a committee that invariably quarrelled, compromised and relied on guesswork.

Even without the World Cup to provide definitive evidence, the England team appeared to be heading for a reckoning, sooner or later. No longer could they travel to the Continent on an end-of-season tour and expect the red carpet to be rolled out by an awestruck team of opposing amateurs who would be duly crushed by a cricket score. During the 1930s, there were defeats abroad to France, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Belgium, Switzerland and Yugoslavia. In 1934, England returned to Budapest, the scene of their first forays abroad back in 1908 and 1909, where they’d won 7-0, 4-2 and 8-2. The intervening years, however, had reduced the gulf between the two nations dramatically, and two second-half goals gave the Hungarians a famous victory. The result was greeted in Britain with the obligatory combination of pessimism – the Daily Mirror lamented a ‘severe blow’ to the ‘prestige of English Soccer’ – and justifications, with the newspapers arguing that the pitch was ‘like iron’, dust affected the players, the heat was unseasonable and the ball was lighter than the English were accustomed to.

In 1936, for only the second time since the war, England lost more games than they won in a calendar year. The English, however, held steadfast in their belief that they remained the apogee of international football, emboldened by a pattern of vengeance that emerged during this period. Though they could be defeated away from home, often (it was claimed) after being handicapped by external factors ranging from lax refereeing, to travel fatigue, to unfamiliar climate, to alien food, at home England remained imperious against Continental opposition. In 1931, two years after they fell in their first ever defeat to Continental opposition in Madrid, England crushed La Roja 7-1. Czechoslovakia and Hungary were both defeated in return matches in England. France, who arrested a run of eight straight defeats to England with a win in Paris in 1931, were then beaten at White Hart Lane and Stade Olympique de Colombes in the following years.

There were also signal performances, the strength of which could not be denied by even the most fervent of Anglophobes and critics of the team. One came in Berlin in 1938, with a match that lives on in infamy. Before kick-off, the English players were press-ganged by British diplomats into offering a ceremonial fascist salute to the crowd and gathered German dignitaries, including Rudolf Hess, Joseph Goebbels and Joachim von Ribbentrop, an indication of the growing political cachet of the game.

What is less clearly remembered is that England came away 6-3 winners after a stirring performance against the cream of not only German talent, but the remnants of the 1930s Austrian Wunderteam, following Germany’s annexation of their neighbours. The Guardian’s somewhat condescending write-up of the game was typical of the imperialist mindset, reminding its readers that the progress made by the German team was a direct result of Britain’s benevolence in sending ambassadors abroad decades earlier. The Sports Argus followed suit, declaring that England’s win, along with a victory for Jimmy Hogan’s Aston Villa over a German select team, had shaken ‘the foundations of the international football world’, before conceding that thanks to Britain’s tireless missionary work, ‘the pupil is now almost, if not quite, the equal of the teacher’.

The German press were simply enchanted, with Fussball Woche consoling themselves that their nation’s defeat had come at the hands of football’s true ‘unparalleled champions’. A year later, a 2-2 draw with reigning two-time World Cup winners Italy in Milan underlined the Three Lions’ claim to still be the best in the world.

Within months of these games against Germany and Italy, Britain would find herself locked in a very different and altogether more consequential battle with the two countries. For the second time in the twentieth century, Britain would emerge from a global conflict the winner, but bearing the hallmarks of having achieved a pyrrhic victory. The First World War had stretched the empire to breaking point, causing the first significant tears to appear. The Second World War accelerated the process, ripping apart the very fabric.

Nations that had sent their men to fight and die for Britain under the banner of opposing tyrannical fascism now demanded that they be afforded the basic rights that they had been fighting in the name of. America’s assistance during the war came contingent on Britain decolonising once the conflict was over, and two years after D-Day, India, the jewel in the empire’s crown and the key domino in the break-up of the empire, had her independence. More than twenty different nations would follow over the coming years. Those that weren’t granted their independence peaceably looked to take it by force. Over the next decade, both Britain and France would fight increasingly desperate – and bloody – battles in the vain hope of preserving their empires.

The war, though ending in an Allied victory, had also made it clear that some parts of that alliance were more equal than others. At Yalta, Winston Churchill had been reduced to a junior partner, a glorified spectator watching on as the USA and Soviet Union carved up the spoils of the conflict and remade the global stage with themselves at the very centre. To add to the indignity, France and Britain, for centuries two of the world’s greatest superpowers, found themselves reduced to relying on vast sums of American aid to help rebuild their flattened cities and tattered economies.

3

POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE

To be a follower of football in Britain immediately following the Second World War was to survey a landscape every bit as devastated as the smouldering ruins of the country’s bombed-out cities. Dozens of players were killed on active duty, while countless more lost the best years of their careers. Clubs were in various states of financial ruin, their previously healthy coffers emptied by the loss of crowds, who feared gathering en masse and didn’t want to risk doing so only to see rag-tag teams of guest players (many First and Second Division sides resorted to fielding well in excess of 100 players during the war years).

Manchester United would play their home fixtures at the Maine Road home of their bitter cross-city rivals Manchester City, until 1949, after Old Trafford was all but levelled by German bombing raids. Miraculously, no football league clubs succumbed to financial oblivion, though many resorted to effectively shutting down during the war, not partaking in even the hastily organised wartime leagues due to the small number of hardy souls still willing to brave live games not coming close to covering the costs of hosting a match.

Club directors and owners could at least take solace in the fact that once the horrors of the Second World War abated, they could look forward to returning to a state of affairs that had never been so good. The 1938 season had seen the third-highest average First Division attendance in history. Attendances for the national team when playing at Wembley dwarfed those of the national rugby and cricket teams, even as the metropolitan elites of London continued to denigrate football as existing on a lower intellectual and cultural plane than the traditional fare of Twickenham and Lord’s. What’s more, attendances had surged following the hiatus caused by the First World War, with returning soldiers and those who had remained at home alike desperate for a return to normality and finding it in the weekly, working-class ritual of going to the match. There was nothing to suggest the same pattern wouldn’t repeat itself.

When football did finally resume amid a burst of post-war euphoria, there had been an undeniable changing of the guard. In the twelve seasons before the Second World War had broken out, Arsenal, managed first by Herbert Chapman and then George Allison, had won five titles, while Everton, inspired by the absurd goal-scoring feats of Dixie Dean, had won three. It would take a decade before another pair of dominant, dynastic teams – Matt Busby’s eponymous Babes at Manchester United and Stan Cullis’ irrepressible Wolves – emerged. In the void came a footballing morass in which eight different teams would win the next nine championships. The twin mechanisms of the maximum wage, which disincentivised players from agitating for moves to earn more money, and the retain-and-transfer system, which wedded players’ registrations to their club and prevented them from obtaining free transfers after the expiration of their contracts, helped encourage this egalitarian state of affairs, as the clubs who had come through the war less financially scathed than others weren’t able to hoover up talent from less-monied teams.

And there was plenty of talent to hoover. Even as fans mourned the loss of many of the heroes of the pre-war years, it was impossible to resist the excitement that built around the new crop of players who emerged, moulded by their time serving in the forces and guesting for clubs and armed forces teams.

Few league debuts in history can have been greeted with such fanfare and anticipation as Tom Finney’s. Having begun his career during the war years and turned in some eye-catching performances in the 1945–46 FA Cup, which resumed a year before the leagues did, Finney had to wait only four weeks after his first league appearance for Preston North End before he received his maiden England cap. It was to be the start of a glittering career, in which Finney haunted the dreams of the myriad defenders who attempted to stop his surging runs. As if to underscore football’s status as the working-class game, Finney supplemented his wages throughout his career by working as a plumber, earning him the immortal moniker of the ‘Preston Plumber’, with his teammates often referred to less charitably as Finney’s ‘ten drips’.

A few miles south, in Bolton, where the outstanding forward of the late 1930s, Tommy Lawton, had been raised, Bolton Wanderers discovered their own enduring talent, plucked from Lancashire’s coalfield, named Nat Lofthouse. A bulldozing centre-forward with an innate finishing ability, Lofthouse formed a lifelong friendship with Finney, and the pair would eventually share the goal-scoring record for the national team.

On the coast, Blackpool’s answer to Lofthouse came in the form of Stan Mortensen, a less physical but no less predatory goal scorer, while Newcastle United had Jackie Milburn as their marksman. In Yorkshire, English football’s first South American star arrived in the form of Barnsley’s inside-forward George Robledo, a Chilean who would go on to achieve legendary status with Newcastle.

The counterbalance to this infusion of attacking skill and power came in the form of a new class of outstanding defender, no better exemplified than Wolves’ Billy Wright and Southampton’s Alf Ramsey. Wright, a dominating, powerful defender of great versatility, would become the first England player to amass more than 100 caps, a remarkable feat given the national team typically only contested between seven and nine fixtures a year during his career.

Ramsey, meanwhile, lacked Wright’s raw physical attributes but was feted for his unparalleled reading of the game and the tactical inquisitiveness that this ability engendered. This was only heightened when, in 1949, Ramsey was bought by Arthur Rowe’s Tottenham, whose daring push-and-run style distinguished them from the direct English norm and saw Spurs win the league in their first season back in the top flight, in Ramsey’s second year at White Hart Lane. With the W-M formation used universally in the English leagues, placing little emphasis on the centre of the pitch, the left- and right-half remained relatively unglamorous positions designated to indefatigable workhorses, who were tasked with racing back and forth between the defence and attack for 90 minutes. Few players did so with such gusto and verve as Jimmy Dickinson, Mr Portsmouth, who would set a record for league appearances for a single club that has only been broken once.

It wasn’t only in the playing department that fresh blood was being introduced. The post-war era dawned with Manchester United a slumbering giant that hadn’t won any significant silverware since 1911 and had spent most of the 1930s in the Second Division. In their quest to return to their earlier halcyon days, the club turned to the untested pairing of Matt Busby, who had made his name starring for United’s two biggest rivals, Manchester City and Liverpool, as manager and Jimmy Murphy as chief coach. Even after the initial success the two enjoyed with the team they built shortly after the resumption, few could have predicted the seismic impact Busby would go on to have on the British game.

For a lucky few who had debuted before 1939, the war hadn’t robbed them of their best playing years. Blackpool’s defensive rock Harry Johnston remained an enormously reliable presence who won the FWA Footballer of the Year for 1951. A year earlier, the same accolade had been received by Joe Mercer, who had moved to Arsenal from Everton and captained the Gunners to league and FA Cup success.

At the other end of the pitch, Tommy Lawton remained the benchmark for strikers across the league, even as players who had grown up idolising him were now playing against him. Lawton moved to Chelsea, where he picked up where he had left off, scoring twenty-six times in thirty-four games and re-establishing himself as the undisputed owner of the England No. 9 shirt.

Of course, no player exemplified the transition from interwar to post-war period in English football more than Stanley Matthews. Before the war, Matthews had been one of the biggest draws in the league, mesmerising crowds and humiliating defenders with his acceleration and trademark body swerve. Matthews was 30 in 1945 and had lost what, for most players, would have been his prime years. Despite helping draw punters to England wartime internationals with unerring consistency, it was felt that his career would soon be on an inextricable downward trajectory, particularly with his style of play being so reliant on bursts of pace and deft skills, both the domain of younger players.

Nonetheless, even with the assumed waning of his magic, Matthews continued to attract fans in their droves. Matthews’ force of character, aided by his popularity, meant he was one of the few players of the time who was able to successfully agitate for a transfer, something that won him no fans in the national team selection committee, which comprised largely club chairmen. Moving to Blackpool in 1947, he was asked by his new manager Joe Smith if he thought his 32-year-old legs could stand the rigours of two more years of first-class football. Smith, like millions of others, would soon be forced to reckon with Matthews’ apparent footballing immortality.

Matthews may have been capable of overcoming the loss of his prime, but countless others were left with a yawning gap in their careers filled with could-have-beens. England and Arsenal captain Eddie Hapgood, one of the great full-backs of his day, was 30 as the war broke out and never played a first-class game again. Another Arsenal star, prolific centre-forward Ted Drake, was only 27 in 1939, but his career was ended by injury almost as soon as football returned after the hostilities. T.G. Jones, Everton’s Welsh defender considered by many the best there had ever been, returned to find the Toffees’ championship-winning team dismantled and himself subject to bitter accusations of feigning injury to avoid wartime matches. Then there were the footballers who didn’t come home at all. Bolton captain Harry Goslin and Liverpool player Tom Cooper were just two of dozens of professional players killed during the conflict.

* * *

While club football staggered to reassert itself, English fans could at least look to their national team with a continued sense of pride. Though the FA and British government were yet to have their eyes opened to the rich vein of diplomatic possibilities football offered, the role that the national football team was nonetheless already playing as a tool for patriotism and as a proxy for Britain’s former economic and military successes abroad was unbounded.

Appropriately enough, given their increasing role within British foreign policy, the England national team were controlled almost entirely, via the FA, by men who had been schooled in the unimpeachable might, righteousness and divine purpose of the British Empire. This mindset tended to encourage a unique degree of arrogance, entitlement and, above all, a nationalistic streak that often lurched beyond pride into jingoism and a self-serving, infantilising belief that because of the sheer vastness of the empire and the role Britain had played in the world order, there was nothing she could learn from any other nation, even as she plundered these nations’ resources.

This belief could be detected in every class and creed in Britain, though it unquestionably grew more pronounced within the higher echelons of society, and by the 1940s, it was entrenched beyond all reproach. Football was, in the words of Bob Ferrier, an ‘old man’s game, run by a class philosophically opposed to anything new’. 1

Post-war Britain would quickly become the scene of pitched battles between this establishment and those who recognised the writing on the wall for Britain’s status and the need to modernise, favouring collaboration over colonisation. In the FA’s case, this man was Stanley Rous, the organisation’s secretary. A former FA Cup final and international referee, Rous was unusual in an association populated largely by businessmen and grandees in that he had direct experience of the game as it was played on the pitch. During the chaos of the war, the forceful, strong-willed Rous began to scheme about how he could encourage some long-overdue modernisation of the FA and the national team.

With the unfettered supremacy that England had enjoyed over all opposition beyond the British Isles for the first four decades of international competition now under threat, the impetus was on England to evolve. Almost immediately, Rous faced opposition from those in the FA who wanted no alteration to the decades-old status quo that had granted them the golden combination of huge power over the running of the game and the national team with very little accountability. Rous was hardly a radical – legendary football scribe Brian Glanville characterised him as ‘a snob and authoritarian’, who seemed ‘almost embarrassed’ that his professional elevation in the world ‘all depended on young men in shorts running about muddy fields’ 2 – but he was, compared to the men surrounding him, at least enterprising. Before long, he was focused on two areas that would enable the England team to evolve, albeit at a glacial pace compared to foreign teams.

Firstly, Rous brought an end to England’s self-imposed isolation. After their withdrawal from FIFA in the 1920s, the British nations had been marooned, largely keeping it within the family by contesting the annual Home Championship and engaging in sporadic foreign tours. The upshot of this was that England missed the first three World Cups, despite a speculative invitation from FIFA to participate in the 1938 competition, a proposition that Rous was amenable towards but one that he couldn’t persuade the rest of the FA to accede to.

In 1946, however, Rous’ campaign achieved success. England, along with the other British teams, re-joined FIFA, paving the way for their participation in their first truly international competition. Immediately, the 1950 World Cup became an enormous draw, even allowing for the fact that it would take place in Brazil and thus entail an arduous journey for European teams. Setting all arrogance aside, there had been an undeniable sense that without the British teams involved, the first three World Cups had been somewhat lacking in legitimacy; the reverence that the game’s progenitors were held in meant that winning the World Cup without British teams was not enough to be truly considered World Champions.

Rous was also agitating for a remarkably basic concession from the FA to bring England into line with just about every other major footballing nation of the time – installing a manager. Teams such as Italy and Austria had already demonstrated the benefits of having forceful managers unafraid to put their stamp on their sides, both achieving enormous success during the 1930s. England, meanwhile, had remained a shapeless mass of players chosen on the whims of the FA’s selectors and sent out without so much as a focused training session or pre-match pep talk, something which had astonished Italy’s legendary manager Vittorio Pozzo. 3