Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

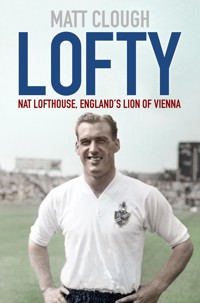

Shortlisted for the Telegraph Sports Book Awards Biography of the Year. Nat Lofthouse is a name that rings through the annals of English football history like few others. He was a pivotal figure in one of the true golden ages of the beautiful game, ending his career as the leading goal scorer for both his club and his country, with a reputation as one of the game's true greats. His retirement coincided almost exactly with the abolition of the maximum wage, and ensured that his name would forever be identified with a time before money flooded the game and changed it inexorably. Lofty explores not only Lofthouse's life and career in detail never done before, but also delves into his personality and motivation through various key points of his life. Matt Clough uses interviews with those who knew him best and played alongside him, extensive research into newspaper archives and, of course, the words of the man himself to breathe life into one of football's most legendary figures.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 500

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustrations: front: Nat Lofthouse in August 1955. (Barratts/S&G and Barratts/EMPICS Sport/PA Images) Back: Nat leads out teammate Bryan Edwards as Bolton Wanderers captain. (Bolton News)

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Matt Clough, 2019

The right of Matt Clough to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9277 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by John McGinlay

Introduction

1 Bolton, Lancashire

2 Early Years

3 Signing for Bolton

4 The War Years

5 First Taste of the First Division

6 Becoming the Main Man

7 The Lion of Vienna

8 Matthews’ Final Heartbreak

9 Taking on the World

10 A Legend is Born

11 Wembley Redemption

12 The Final Curtain

13 Managerial Misery

14 Wanderers’ Saviour

15 Full Time

Appendix: Career Statistics

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

FOREWORDBY JOHN MCGINLAY

BOLTON IS SPECIAL, and what makes it special is the people. They made me so welcome on the day I signed, 30 September 1992, and even now, almost 30 years later, I’m still treated the same way. When the team does well, the town does well. When they’re winning, there’s a buzz. They’re proud of their football club, so it’s important that it’s protected, successful and run well.

Nobody did more to make that happen than Nat. I first met him the day I signed for the club. I was in awe of him. I knew his history, I knew what he meant to the football club. But what really struck me was that he was so down to earth. He was such a gentleman – just a fantastic man.

Coming into the football club as a striker, with all Nat had achieved, could have been a bit intimidating, but I never felt that with Nat. He was always approachable, someone that you could talk to and bounce things off, and it helped me greatly. And not just me – all of the players. If you were going through a bad time, maybe hadn’t scored for a few games, maybe a loss of form, he’d quietly put his arm around you and take you for a little walk.

He’d always just say ‘keep going cocker, keep playing cocker, things will turn out right’. It was just such a boost for someone like that to take the time to do that. He’d never growl ‘come on’ or anything – he’d just speak to you, and nobody would want to let him down, because everybody knew what it meant to him. In fact, he was the type of guy who would encourage you to beat his records, without any remorse, because it would have meant you’d be doing well for his football club. That was all that mattered to Nat – it was his football club and he wanted to see it do well.

And we saw him every day. At training, the big matches, and the big moments of my time at the football club. The Play-Off Final in 1995 was an unbelievable day. There was an interview with myself and Owen Coyle and Sir Nat, and he kissed me on the cheek! The delight in his eyes that day – this was his club getting back in the big time. He was skipping around Wembley like a 20-year-old.

The nights at Liverpool, the nights at Highbury – he was at all of them. You could look up from the pitch into the director’s box, and he’d be there, beaming. When I was called up to Scotland, there was nobody prouder than Nat. He came in and shook my hand and said, ‘I’m chuffed for you, cocker, magnificent.’ He was proud as punch, as much as if I’d been going to play for England.

He never mentioned that I was making my debut in the same stadium where he scored his famous goals against Austria. That was the thing – when he talked to you it was always about you. He never mentioned playing for England or anything like that. He could have had us in awe, but he never spoke about himself. That was the difference with Nat.

I suppose that, in a way, I’m a bit like Nat was when I first joined the team. If anyone says a bad word about Bolton, I’ve got to have a go! I love this football club, and I feel like if I don’t defend the club, I’m letting Nat down.

He would have done anything for Bolton Wanderers. It was his football club, and he was the heart of this football club. I hope nobody ever forgets that.

John McGinlay2019

INTRODUCTION

IT WAS ONE of those moments that seemed to happen in slow motion, yet all at once. As soon as Gil Merrick had the ball in his hands, he couldn’t get rid of it fast enough, flinging it to the first red-shirted England player free from the attentions of an Austrian opponent that he saw. To the Three Lions’ good fortune, the player he found was Tom Finney, Preston North End’s brilliant, electric winger, midway inside England’s half. As quick of mind as he was of foot, Finney was already renowned in 1952 as one of the most incisive, exceptional players that his country had ever produced. On this occasion, under leaden skies on a warm, muggy day in Vienna, in front of more than 65,000 hysterical fans, he needed but a pinch of his usual passing acumen to know what to do as he brought the ball down and spun towards the Austrian goal. Ahead of him was only one England player, and Finney wouldn’t have wanted anyone else there, even allowing for the fact that the man in the number nine shirt was his best mate.

Nat Lofthouse didn’t need to stop and think about what to do as Finney laced the ball through to him. It was the same thing he’d been doing for the past two years for his country, for eleven for his beloved hometown club Bolton Wanderers, and for as long as he could remember before that: scoring goals. ‘I could hear the hounds setting off after me but I knew it was basically down to me and [Austrian goalkeeper Josef] Musil,’ Nat remembered. His face, which usually wore a beaming, slightly lopsided grin, was set in an expression of grim determination. Using his deceptive speed, he began to race toward Musil’s goal. Such was the distance he had to cover that various thoughts had time to flash through his mind. The prospect of scoring the winning goal against the fearsome Austrian team, without doubt his most significant contribution to England in his seventh cap. The opportunity to make some of Britain’s leading sportswriters, who had called for ‘Lofty’ to be replaced by Newcastle United’s Jackie Milburn, eat their words. With his heart racing, he noted Musil seemed caught in two minds, not knowing whether to rush out to meet Nat or stay on his line and take his chances.

After some hesitation, Musil did advance. Nat sensed an Austrian defender gaining on him, but kept his cool. He and Musil were now steps away from one another but still he kept the ball. Just as he, Musil, and the defender all converged, he calmly picked his spot and shot, sliding the ball past the onrushing keeper and into the net. As the small pockets of British servicemen in the crowd, many of whom had staked an unwise amount of pay on the dim prospect of an England victory, went into a frenzy, Lofthouse and Musil crunched into one another with a sickening thud. It would take several moments for Nat to come to. When he did, he was met by his massed teammates, their faces a mixture of concern for their stricken ally and ecstasy at what his sacrifice had earned. It was then that he learned he’d just scored the most significant goal of his career, one that would enshrine him for evermore in football folklore as ‘The Lion of Vienna’.

It was a goal that typified everything Nat Lofthouse was as a player. Surprisingly fleet of foot despite his muscular frame, he had a composure in front of goal that one simply couldn’t learn. The lethal, predatory instincts that saw him score 315 goals in 536 league and cup appearances for club and country (every single one he considered himself ‘fortunate’ to have scored) were allied with an incredible strength that earned him a reputation as an often unstoppable aerial threat. Nat was rarely more than self-deprecating about his abilities, never tiring of repeating what his coach George Taylor had told him: that he could do only ‘three things – run, shoot and head’. While characteristically humble, this analysis of his game left out one potent part of the Lofthouse formula, one that set him apart from his peers even in an age when football was at best rugged, and at worst downright brutal. Nat was utterly fearless, almost to the point of foolhardiness, an irresistible force of nature. In the words of Tommy Banks, another legendary Bolton Wanderer who too enjoys a reputation based on his otherworldly bravery on the pitch, Nat ‘never shirked ’owt’. By the end of Lofty’s career, he’d have the souvenirs – gruesome scars, reset bones, bloodied shirts – to prove it.

Not only did the goal in Vienna demonstrate exactly what made Nat Lofthouse great, but also what he has come to represent as one of the standard-bearers of his era of football. Indeed, many of the features we traditionally associate with players of his day – the tough upbringing, the undying loyalty to their club, the down-to-earth humility, the ‘man of the people’ status – undoubtedly borrow from Nat’s own story.

With his achievements slowly fading into the mists of time, he, like so many of his contemporaries, has been venerated to such an extent that he is closer to a Roy of the Rovers caricature than a real player. Delving into the story behind the legend reveals a more complex, yet no less remarkable, story. Nat Lofthouse was a man who reached the pinnacle of the game not through raw ability alone but with remarkable grit and determination; whose famous loyalty to his club was put to the test and, at times, stretched to breaking point; whose fearsome nature on the pitch belied a friendly, approachable demeanour; and who, perhaps more so than any other sole person, played a pivotal role in shaping one of English football’s great clubs. Tom Finney hailed him as ‘the King of Bolton’, a man who he was ‘proud’ to call a friend.1 Tommy Banks calls him ‘magic’. Dougie Holden, another member of the famous 1958 FA Cup team, describes him as a ‘powerhouse’ and ‘a great man’. Stan Matthews called him a ‘lionheart’.2 Gordon Taylor, now head of the PFA, watched Lofty from the Burnden Park stands as a boy and had ‘never seen anything like him’. Thousands of Wanderers fans who watched Nat play or had the good fortune to meet him off the pitch describe him, simply, as ‘the greatest’. This is the story of Nat Lofthouse, the man they called the Lion of Vienna.

1 Nat Lofthouse & Andrew Collomosse, Nat Lofthouse: The Lion of Vienna, pp. v–vi.

2 ‘With Lofthouse at his best we slammed the Scots 7-2’, South China Sunday Post Herald, 1965.

1

BOLTON, LANCASHIRE

QUITE WHAT COCKTAIL of emotions was swilling around Nat Lofthouse’s head as he walked out on to the Burnden Park pitch on a cold, damp March day in 1941 only he knew. The fact that this was the first time he was wearing the famous white shirt of the club he’d supported fanatically since childhood would have been enough to have even the hardiest soul balancing a mix of ebullience and sheer, unadulterated terror. But these were exceptional circumstances.

Unlike many modern players, mollycoddled through years within academies and gentle loan spells before being gradually eased into the first team, Nat’s situation was very much a case of being thrown in at the deep end. He had signed his amateur papers with Bolton Wanderers the day after Britain had entered the Second World War, eighteen months earlier, and had learned of his imminent first-team call up not on the training pitch, but on the factory floor where he was working. Though already in possession of the robust frame that would serve him well for years of bone-jangling tackles and wince-inducing head clashes, he was still a boy of only 15. As he plodded across Burnden Park’s gravel track and on to the pitch, the thick cotton shirt bearing the club’s red crest hanging loose on his body, the players surrounding him weren’t the heroes he’d grown up watching. Instead, they were a ragtag group consisting of just about anyone who manager Charles Foweraker could get his hands on.

An unfamiliar name on the blackboard paraded around Burnden Park to display the team was nothing new to the 1,500 fans smattering the ground that day. For those in the know, seeing a local lad make his debut was always a matter of pride, invariably dampened by doubts over whether he could truly make the grade. Bolton fans had a reputation for being harsh yet fair, and as usual there was to be no quarter given or allowances made for the 15-year-old’s rawness and lack of experience. The world was at war, and many of those in the stands that had yet to be called up knew plenty who had and that their time may well soon come. The local economy, which had been slowly decaying for years, was in danger of falling apart. Those that would still have jobs when the conflict ended could look forward to dangerous, back-breaking work that paid barely enough to survive. Quite simply, they needed Bolton Wanderers, one of their only forms of escape, to give them something to cheer about.

To tell the story of Nat Lofthouse is to tell the story of Bolton Wanderers, and to tell that story, it’s vital to understand the town and those who inhabited it. The game of football has been called many things over the years – a passion, a devotion, a religion – and rarely have these epithets more readily applied than to those in the North of England during the dark, desperate years of the early 1940s.

History favours periods of extremity. It is for this reason that we know all about the 1920s and ’30s in the USA – the former a period of exuberant, opulent wealth, the latter of devastating, previously unfathomable desperation – but less of the state of Britain, which followed a similar, albeit less severe trajectory. The ‘Roaring ’20s’ were more of a tepid mewling, while the Great Depression merely exacerbated many of the country’s pre-existing ills. Lancashire’s economic bedrock, coal mining and cotton production, was relatively insulated from the collapse of the world’s financial institutions in October 1929, but their stability during these years doesn’t tell the whole story.

The textile industry was the county’s most critical, effectively employing entire towns. As late as the end of the nineteenth century, Lancashire held a virtual monopoly on cotton production. The Empire had an unrivalled expanse, trade relations with key markets were good, and the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution made transporting the goods spun in the mills of towns such as Bolton, Preston, Oldham and Rochdale a simple task. It seemed like nothing would be able to topple Lancashire as the best cotton-manufacturing region in the world. But all that was to change. A combination of mill owners’ reticence to modernise their methods and invest in new machinery (after all, if it wasn’t broken, why try to fix it?) and the inability to export during the First World War ultimately set Lancashire’s most valuable industry on the road to ruin. In the lull created by the Great War, two of Lancashire cotton’s biggest markets, India and China, moved to plug the gap by manufacturing raw cotton themselves. By the time the conflict was over, so was the North-west’s dominance.

Mining was a similar story, although one playing out on the national stage rather than just the local one. It remained, as it always had been, a remarkably treacherous way of earning a living, with numerous respiratory problems and physical injuries awaiting those who survived long enough to retire. As with the mills, enough technological innovations had arrived to put men out of work, but had failed to make mining any less gruelling or more immune to shifts in the world economy. The speed with which new drills were able to cut through the shelf was such that the age-old technique of propping the ceiling up every few feet was abandoned in the name of penny-pinching efficiency. Both the noise and the vibration generated by the machinery exacerbated the already very real risk of cave-ins and other disasters. In 1910, 344 men were killed in an explosion at the Pretoria Pit in Westhoughton, 4 miles from Bolton, after a cavity filled with gas was ignited by a faulty headlamp.

Most pits were organised into three distinct shifts per day, usually around eight hours in length, not including the time it took the miners to creep down the narrow passages from the main shaft to the coalface, which could easily add another hour either side of the shift. If this wasn’t hard work enough, most did it largely on an empty stomach; food had to be taken to the coalface, and so tended to get ruined almost as soon as it was unwrapped. After finishing and returning to the surface, the miner went home with about 9 shillings in his pocket and the promise of a wash in a tub of cold water. And, as unfathomably exhausting, financially miserly and generally nightmarish as this sounds, the one worry that trumped all others in each man’s mind as he tried to sleep was whether the colliery would have enough work to give him the chance to do it again the next day.

By the twentieth century, the pattern was virtually set in stone. Men went down the mines or, if they were lucky, had factory work. Women either stayed at home or worked as spinners in the mills depending on how hard up the family was (for many, it was usually a case of somewhere between ‘badly’ and ‘unbearably’). Down the cobbled streets, trodden by milk girls in wooden clogs and on which scruffy kids kicked a ball made from whatever they could find, row upon row of houses were packed tightly. In Bolton, it wasn’t unusual to find these already modest homes subdivided into tiny rooms by unscrupulous, uncaring landlords determined to eke out every last penny from the squalid, claustrophobic conditions as they could. Frequently, multiple houses shared the same toilet. With so many families and lodgers crammed into a space meant for a comparative few, it was all too familiar to encounter a queue for the facilities in the dead of a bitter winter night.

For some, the remnants of the Industrial Revolution – the rows of houses, the towering factories, the billowing chimneys – that had once represented hope and ambition became merely another tool of the gloom. Not only were they reminders of the broken promises of prosperity, but they brought with them illness and disease, exacerbated by the cramped living conditions. Any potential industrial investors in the North-west only needed to enter the labyrinth of sorry lodgings surrounding their prospective factory and cast their gaze on the sickly, broken workforce to quickly take their business elsewhere. One prospective player for the Bolton Wanderers football team, George Eccles, was warned by a doctor not to sign for the club lest he wish to jeopardise his health. The Bolton climate, the physician declared, was ‘lethal’.1

In 1936, a writer was commissioned to travel to Lancashire and Yorkshire to document the lives of the most impoverished. A keen analyst of people, their characters and conditions, and already in possession of an innate sense of social justice, the journey was a sobering and formative experience for the young man. The resulting account of his journey, The Road to Wigan Pier, talked at length about the lamentable, squalid conditions that many working-class families found themselves in. The meagre portions of flavourless food totalled an ‘appalling diet’. The mines were his ‘own mental picture of hell. Most of the things one imagines in hell are in there – heat, noise, confusion, darkness, foul air, and, above all, unbearably cramped space.’ Living arrangements bred disease and homes were infested with insects. While some contemporary critics suggested that the account was sensationalised, there’s no doubt that life in 1930s Lancashire was almost unimaginable by modern standards. Twelve years after The Road to Wigan Pier was published, George Orwell published another work, Nineteen Eighty-Four. In its dystopian view of the future of Britain, a tiny elite have engineered a totalitarian system that keeps the working classes in a constant state of economic and social depression. It isn’t difficult to see from where he took inspiration.

Another bastion of early twentieth-century British culture, acclaimed artist L.S. Lowry, spent much of his professional life living and painting Pendlebury, a small town less than 6 miles outside Bolton. His body of work remains a fascinating glimpse into not only the world that the people of Lancashire lived in during the early 1900s, but of the people themselves. Invariably, his paintings were dominated by the industrial landscape, with the people depicted as wraithlike shadows, victims of their often shattering circumstances.

However, despite the almost irresistibly grim situation many had to contend with, an unbreakable spirit prevailed. Although many thousands abandoned the North-west in search of better prospects in the 1920s and ’30s, rather than splintering communities, it only served to drive those who remained closer together. With so many crushed into a tiny area, inevitably you got to know just about every face that you saw on a regular basis. The lack of diversity in employment meant that if a man didn’t work with another at Mosley Common Colliery or one of the other nearby pits, their wives may well have been sat at neighbouring spinning machines at the Bolton Union cotton mill. There was scarce money for recreational activities, so children had to make do by getting together in large groups and inventing games on the street. Even holidaying was a communal activity for those lucky families able to afford an annual trip. Blackpool’s Pleasure Beach, just a short train ride from Bolton, was the destination of choice. With the pits generally shutting down for the same two weeks in the summer, it was like the whole town upped sticks for a jolly.

With the pits taking lives on a regular, indiscriminate basis, malnutrition and disease quickly robbing communities of some they’d known for years, and infant mortality rates in some areas of Lancashire rivalling those of Victorian times, the people of Bolton had little choice but to try to make the best of things. Orwell noted a common practice of families squirreling away some of their meagre food budget in order to buy something sweet to break the dietary monotony. Pubs were crammed to the rafters on the weekends, offering a brief chance to forget the dire straits of modern living and catch up with colleagues without having to yell over the din of the mining equipment or the weaving machinery. Dances and music shows were held at places like the Palais de Danse and the Empress Dance Hall in the town centre, giving the younger generation a furtive glimpse of a more glamorous lifestyle, as well as the opportunity for some dalliances of a romantic nature. The football pools, which involved predicting the outcome of matches to win a substantial prize, offered working men and their families a weekly source of hope that maybe, just maybe, this time it would be them. And, of course, there was football itself. While it may seem trite to suggest that the sport cured any of society’s ills, the fact that the dawning realisation of the cotton and mining industries’ inevitable demise in the ’20s coincided with the white-shirted Bolton Wanderers becoming one of the country’s most successful sides undoubtedly kept spirits up among the tens of thousands of people who crammed themselves into the paddocks at Burnden Park on Saturdays.

Like most major teams across the country, Bolton Wanderers could trace their origins back to the previous century when rapidly growing interest in football, buoyed by a countrywide desire to cast off the shackles of working during the Industrial Revolution, saw the number of clubs explode. One of the trailblazing teams in the Bolton area were a church side from Deane Road. Christ Church FC appeared nomadically on the shrubland and fields around the town during the mid-1870s before eventually settling on a rented field off Pikes Lane. Frequent meetings between those with a stake in the club demonstrated an increasing level of professionalism, and the club began to accept those beyond Christ Church’s traditional congregation. However, there was a sticking point. The vicar’s autocratic temperament was, in the opinion of the others involved in the team’s business, becoming something of an issue. On 28 August 1877, the committee members took the decision to rename the team and cut ties with the church, at once increasing their catchment area of potential players and fans and ridding themselves of a nuisance that could hinder the progress of the club. Bolton Wanderers Football Club – so named because of the team’s lack of fixed abode – was born.

Progress was rapid. The team remained on the rented pitch, but crowds swelled considerably from a few stragglers to thousands. By the early 1890s, the team was attracting gates of almost 15,000 for local derby fixtures and collecting hundreds of pounds in ticket revenue. The popularity of the team reflected the growing profile of the sport across the nation. The Trotters began meeting local rivals in the FA Lancashire Cup in the 1879/80 season, and took their game to teams from up and down the country when they first entered the newly anointed FA Cup in 1882. The early years of the Cup were riddled with numerous replays due to countless appeals and counter-appeals between teams accusing one another of having forbidden paid professionals playing for them. Wanderers themselves weren’t particularly subtle about flaunting the rules on professionalism. Local businesses had been running adverts in Scottish and Welsh newspapers advertising ‘jobs’ for men who would also be willing to turn out for the club. Finally, in 1885, the FA decided to make paying players a wage legal after several clubs, including Bolton, seceded to a rival football association where professionalism was permitted.

With the advent of professionalism came a new standard of quality.2 No longer did players see club affiliations and playing overall as trifling matters. Now they could make decent money in football, it paid to settle down at one club and work hard. As play improved, demand for the sport continued to snowball, with games being organised on Christmas Day. On 17 April 1888, the Football League was formed, ensuring standardised, competitive football for all participating clubs for the entire season. Bolton Wanderers was a founding member.

Bolton’s early years in English football’s first official league system were highly promising. Wanderers, in their new strips of white tops with navy shorts (they’d previously experimented with pink, red and even polka-dotted kits) narrowly missed out on a league championship in 1892, the final year before tiered divisions were introduced. Two years later, the club had its first experience of an FA Cup Final, where they earned the dubious honour of becoming the first top-flight team to lose the showpiece match to lower league opposition. Chagrined by the rising rent on Pikes Lane, the club’s key players – among them J.J. Bentley, a visionary who foresaw both the communal and commercial possibilities of the team – decided to move. A substantial area by the railway had been bought with the intention of building a gasworks. However, when the venture became financially unviable, the club was offered the land at a discounted rate. The team issued shares and, having swiftly raised the required capital, began construction on the ground that became known as Burnden Park, opening in time for the 1895 season. Boasting room for over 50,000, Burnden would go on to become one of the iconic pieces of English football stadia. Trains moving along the lines that ran beside the ground would often slow to a crawl to allow passengers to take in some of the game. For big games, the Railway Embankment end would become a heaving mass of bodies, a huge crashing wave constantly threatening to engulf the pitch. The freezing winters did little to deter the punters, and as the nights drew in, the ground would become engulfed in pipe smoke during matches. The turf did a fine job of retaining much of the Lancashire drizzle deposited upon it (the Sports Argus wrote that, at Burnden, ‘the mud always seems to be thicker and blacker than anywhere else’3), and the result was a pitch that suited the robust play style of the Wanderers to a tee. A drop of several feet awaited any player who lost his footing on the touchline – a threat made all the more real during the 1950s when Tommy Banks and Roy Hartle ruled the flanks.

For the first decade and a half at Burnden Park, Wanderers lived up to their name by never truly establishing themselves in either the First or the Second Division, which they bounced between no fewer than eight times. The chief cause of their failings tended to be their inability to forge an effective (or at least consistent) strike force. When they finally did, things changed. Under the stewardship of secretary-manager Charles Foweraker, who had first joined the club in 1895 as a turnstile operator4 and was promoted from the assistant manager role after Tom Mather left to join the navy in 1915, Bolton became a force to be reckoned with, thanks largely to the spectacular play of their forwards.

Two of the mainstays, Ted Vizard and Joe Smith, had been with the club for some time, but the end of the First World War finally afforded them the opportunity to develop an understanding between one another. Vizard was a sublime outside left who played for the club for over twenty years, blessed with a rare, visionary ability to sense his teammates’ movements and create opportunities for them. The true focal point of the attack was Smith, who ended his career with more goals for Bolton Wanderers than any other player and who remains eleventh on the all-time English First Division goal scorers list. Having been at the club since 1908, he was already a veteran by the time he captained the team at the first ever FA Cup Final played at the brand new national Wembley Stadium in 1923. It was here, in front of an estimated 300,000 spectators, that Bolton finally broke their hoodoo and collected a major piece of silverware by beating West Ham United 2-0. Two more Finals, in 1926 and 1929, brought two further titles.

The unprecedented success of the club during the 1920s was a huge boon for the town, a welcome distraction from the growing concerns about the economic climate. The team had everything: flair, a never-say-die attitude that made them a fantastic cup side, and a combination of local lads and some of the best stars sourced from elsewhere in the United Kingdom. It was impossible for any young boys from the town to resist the pull of the glamour, the idolatry and the dizzying amounts of financial remuneration that the players of Bolton Wanderers enjoyed.

Lowry’s paintings may have dehumanised the figures depicted in his landscapes to an extent, but one marked feature of many of his works was the sheer multitude of people, hinting at a collective social spirit that defied economic realities. One of his most memorable pieces, Going to the Match, depicts fans heading into Burnden Park. The stick-thin bodies of men and women, young and old, are bent head-first toward the welcoming turnstiles, bottlenecks before which the concentration of punters naturally swells, a testament to the unifying, intoxicating power of football. Like a visit to the pictures, going to the match offered pure escapism, a chance to forget about the trials and monotony of life, and gave entire communities a common goal to pull for. It was a social event. In The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell wrote of miners ‘riding off to a football match dressed up to the nines’ together, relishing a chance to laugh and cheer along with their co-workers. Football may not have promised any long-term cures for the troubles faced by those in Bolton during the first half of the twentieth century, but its role as the lifeblood of the town cannot be overstated.

This was the world into which Nathaniel Lofthouse was born on 27 August 1925 at his parents’ home, 80 Willows Lane, close enough to the terraces of Burnden Park for the roar of the crowd on match days to be heard.

1 Percy M. Young, Bolton Wanderers, p. 68.

2 The game still had some way to go to considering itself refined. A report from the Football Field newspaper in 1890 offers this account of one of Bolton’s goals against the visiting Belfast Distillery team: ‘A shot came into goal and was well caught by Galbraith, the visiting goalkeeper, who fell to the ground. Thereupon, all the Wanderers attempted to roll him through the posts, whilst the visitors manfully strove to prevent them … More than half the players were struggling in the mud, but eventually the Wanderers managed to drag custodian, backs, and the others through the coveted space, and thereby registered their third point [goal].’

3 Sports Argus, 5 January 1952.

4 Foweraker’s father had done the same at Pikes Lane.

2

EARLY YEARS

THE STATE OF life in Bolton had an effect on everyone who experienced it, even just for a passing moment like George Orwell had. For Nat Lofthouse, the town was in his veins, interwoven with his DNA, forming an indelible part of his character long before he was old enough to comprehend the grand, neoclassical town hall, Ye Olde Man and Scythe pub or Burnden Park. His family’s Lancashire connections stretched back hundreds of years, and since the turn of the nineteenth century, Nat’s ancestors had been born, lived, loved and died in the town, rarely living more than 5 miles apart from each other. It’s little surprise that despite all the remarkable, extraordinary adventures that his career would take him on, he would always call Bolton home. Nat ‘had two families’, he said, ‘the people of Bolton and the Lofthouse family’.

Nat’s paternal great-great-grandfather, and with him the Lofthouse name, had arrived in Bolton permanently in the early 1800s from nearby Ribchester. His great-grandfather, Thomas, was the first of the Lofthouse line born in the town, and spent most of his life as a bricklayer, helping to build the factories, mills and houses that would come to define Bolton’s landscape. Thomas settled down and by the 1880s had his wife, Susannah, a brood of eight as well as a lodger stuffed into 289 Derby Street, a four-roomed Victorian terrace. Thomas’ eldest son, Andrew, was the first in the family not to enter the mining industry, escaping the hellish pits for work as a carter, tramping the streets with a horse and cart, hauling the mineral carved from the ground around Bolton to the homes and businesses that relied on it for warmth and fuel. It was tough, tiring work, but it provided a steady income away from the ever-present dangers of the pits.

One of the men who was toiling in the depths of the mine shaft was William Powell, born the year before Andrew in 1857, who had travelled to Lancashire in the hope of more steady work than was available in his native North Wales. In the late 1880s, both William and Andrew tied the knot, the former to a widow, Sarah Griffiths, and the latter to a local girl named Elizabeth. Marriage was quickly followed in both cases by children. The Powells would have two daughters and three sons by 1901, as well as Sarah’s two daughters from her previous marriage; the Lofthouses had a more modest two sons and two daughters. Although working class, the Daubhill area in which the Lofthouses lived on Willows Lane was prosperous and boasted all the amenities of a well-to-do community. At the turn of the century, tracks were laid on the street for a new electric tramway, run by the Bolton Corporation. The sight of these double-decker marvels of modern science was a rousing statement of intent, demonstrating in no uncertain terms that the North-west remained a thriving economic power – a jewel in the crown of one of the most powerful empires in history – as the Victorian era drew to a close.

One of the Lofthouse boys, Richard, had been born on 24 October 1889, around the time of the Powells’ first daughter together, Sarah. The Lofthouse’s second eldest son followed his father into the carting trade after leaving school, reassured of the occupation’s stability and constant need for workers. More ore was being mined than ever; 1907 saw a yield of 26 million tonnes, the biggest year of production ever. When Sarah went to work in a mill and with Dick carting, their paths eventually crossed. It could have been as simple as her mill being on his rounds. Another possible meeting point was a local dance. ‘Mill dances’ grew in popularity throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Held locally for the workers of multiple mills, the dances were a chance for some much-needed revelry to break up the drudgery of factory work. The high proportion of young women working in the mills was all the encouragement many young men needed to attend, too.

Sarah was a straight-talking, pragmatic young woman with a quick wit and a readily apparent maternal instinct. In Richard, she found a driven, ambitious man whose career in the carting profession had bestowed upon his 5ft 6in frame a tough, hardy physique. On 30 August 1913 they were married at St Anne’s Church in Hindsford. Their marriage certificate lists both living at 27 West Bank Street in Atherton, suggesting that they’d been cohabiting prior to marriage, perhaps with Richard living with the Powell family as a lodger. Although marrying at 24 was fairly typical, Dick and Sarah’s courtship may have been expedited by the massing dark clouds on the horizon. Relations between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires were strained, and across Europe the rumblings of a wider conflict were beginning to be felt.

It wasn’t long before the newly-weds bade farewell to Atherton and moved nearer to Bolton’s centre, just across the way from Dick’s parents on Willows Lane. Dick kept up his tireless work and earned a respectable £2 10s a week. While many couples immediately looked to start families after marriage, the Lofthouses heeded the increasingly fraught signs from the continent, with Sarah’s pragmatic streak dictating that they should wait for the troubles to pass before trying for children.

Sure enough, on 4 August 1914, war was declared when Britain responded to the German invasion of Belgium. Both sides provided assertions that the war would be over by Christmas. In reality, the resulting conflict lasted four long years and became the bloodiest in human history. In typically British fashion, the attitude adopted was one of stoic bullishness. The call for 100,000 volunteers was surpassed almost five times over within two months of the declaration, with Bolton contributing more than its fair share of men. One of those was a carter, who strode confidently into the station in Nelson on 14 September to offer his services for King and country, perhaps inspired by the iconic poster of Lord Kitchener telling each and every man who saw it that the country wanted him specifically. Dick may well have escaped conscription when it was introduced in 1916 due to various jobs in the coal industry being classed as ‘starred occupations’, important enough to the war effort that the country was best served by keeping those men where they were. The fact he signed up just a month after the declaration speaks volumes about his character. The Bolton regiments would go on to face some of the worst fighting of the Great War. The Lancashire Fusiliers and Loyal North Lancashire Regiment both fought heroically at Gallipoli; the Manchester Regiment spent the first year on the Western Front before being dispatched to the Middle East. However, Dick was destined not to be with them.

After just over a month of training, an army doctor ruled that Dick simply wouldn’t be able to ‘become an efficient soldier’. The root of this assessment wasn’t his overall fitness or his mental aptitude but an old injury he had sustained to his hand while completing his rounds one day. The injury prevented him from holding a rifle for a prolonged period of time, and this, combined with the importance of his trade, led to his discharge. The absence of many miners and other carters as part of the war effort meant Dick’s job security was better than it ever had been. Despite the war still casting a fearful gloom over Lancashire – never more so than when a Zeppelin mistook Bolton for Derby and unleashed a payload that killed thirteen and demolished homes on Kirk Street and Derby Street, just yards from where Dick’s father Andrew had grown up – the Lofthouses decided to start a family. Almost exactly nine months after Dick’s army reprieve, the couple had a son, Edward, and another, named for his father, followed just over a year later.

After four years, the German armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, and the Treaty of Versailles some seven months later brought a formal end to the war. Over 16 million had died, roughly 3,300 of whom were from Bolton. As life returned to normal in one respect, it was becoming clear that the Lancashire economic machine was ailing, the competitive advantage that the region held in cotton and coal being eroded by increasing foreign competition combined with local greed and apathy. Dick was one of the fortunate ones in that his years of tireless service for the Bolton Corporation had stood him in good stead and he was never wanting for work. This continued security eventually meant he and Sarah had two more boys: Thomas, born in 1923, and, on a dull, cool summer’s day – 27 August 1925 – Nathaniel. Their youngest son was baptised in the idyllic St Anne’s Church, where his parents had been married twelve years earlier.

The Lofthouses were, like so many families at the time had to be, a tightly knit unit. St Anne’s Church, the site of Nat’s baptism and Dick and Sarah’s marriage, was less than half a mile from where Sarah had grown up and where her parents still lived. Nat’s home, 80 Willows Lane, a modest yet comfortable two up, two down, was just a few doors down from his paternal grandparents. This proximity to the previous generations of the family ensured that Nat and his older brothers1 grew up with a strong sense of family and a constant reminder of the virtues of a hard day’s work. Nat’s father’s long-standing occupation kept him insulated from the gradual suffocation of Lancashire’s industries and the creeping unemployment that came with it, but he never failed to impress upon his boys the importance of an unbending work ethic. Though such an upbringing could have verged on stiflingly authoritarian, it was also a house filled with love, and even before he began his first years of education, the Lofthouse’s youngest son was already demonstrating the happy-go-lucky confidence that so many would remark upon after meeting him as an adult. Already, the beaming, slightly lopsided grin was being worn at regular intervals. Looking back on his earliest years, Nat reflected that ‘although life was not always easy … I enjoyed [it] thoroughly’.

Dick’s wages covered the basics and a few luxuries like the occasional pint or a family trip to the pictures. The latter pursuit was particularly of interest to the young Nat, who grew up spoiled for choice by the countless yarns of heroes and villains, adventures, and damsels in distress from Hollywood’s ‘Golden Age’ that graced the silver screen. Even when he was performing feats worthy of their own big-screen treatment, Nat would always have a love of the pictures (particularly those of John Wayne), just as he would for so many pivotal parts of his childhood. Besides Hollywood, the other pastime of choice in Bolton in the 1920s had a distinctly more British feel, imbued with grit and bullishness. Willows Lane was about 2 miles away from the concrete and steel that made up the home of Bolton Wanderers Football Club, Burnden Park. On match days, when a westerly wind blew, the chants and the roars of often more than 50,000 people supporting manager Charles Foweraker’s men drifted right to the family’s front door. Dick had resisted the overtures, regarding the idea that men could earn more by kicking some cowhide around a park than by toiling down the mine for hours with suspicion. However, the cheers and shouts floating over the terraced roofs proved irresistible for Nat and older brother Tom. The guttural, primal noise had the same effect on them as the Pied Piper’s tune had on the children of Hamelin.

Even without the presence of one of the defining monuments to British football just down the road, football as a sport had already got its hooks into the two youngest Lofthouse boys, with neither needing any encouragement to join in the impromptu street games among neighbouring children. These games were basic to say the least. There was no council spending on local pitches for youths, and little disposable income to pay for specialised boots or even balls. England star Tommy Lawton, six years Nat’s senior and also from Bolton, would remember the pitches of his formative years being the cobbled streets or unoccupied pieces of scrubland, on the days when the weather hadn’t transformed them into mud baths. Some of Nat’s earliest memories would echo Lawton’s: playing with Tom and other local kids with items of clothing for goalposts and old newspaper stuffed down their socks as rudimentary shin pads; ‘We could never afford a proper football, of course, so whoever had the nearest thing was the most important kid around.’

Aged 5, Nat began attending Brandwood Primary School, where his immediate preoccupation was not academics, but rather how to stop them from interfering with his desire to spend every waking moment playing the sport that had captured the imaginations of so many boys of his generation. It’s extremely telling that, when recounting his school days, Nat suggests the most crucial pearl of wisdom he gleaned was that ‘it was impossible to learn all there was to know about football’. He was never short of a self-effacing observation about his lack of aptitude when it came to education, but it’s hard to imagine that his cheeky sense of humour and willingness to try his best had anything other than an endearing effect upon the teachers at Brandwood.

With his decidedly lackadaisical attitude to formal schooling and his insatiable appetite for the game, it was only natural that the thronging crowds headed towards Burnden Park would eventually prove too much for young Nat to resist. Despite being expected at school on Saturday, 18 February 1933, Nat headed east rather than west from Willows Lane, walking down the fabled Manchester Road that ran alongside the Main Stand of the club’s home ground. The fixture that day was an FA Cup derby against Manchester City. Given the geographical proximity of the teams, Bolton’s recent success in the competition and both teams’ league campaigns comprising worried glances toward the relegation zone rather than hopeful looks to the top, it was little surprise that 69,912 supporters, Burnden’s biggest ever crowd, packed themselves on to the terraces on this mild winter’s day.

Despite this being his first ever experience of live football at Burnden, Nat was not among the recorded number of patrons. With even the 1d programme too expensive for him, there was no chance he’d be able to afford the price of admittance through the turnstiles. Schoolboy rates were threepence for the northerly Embankment terrace, sixpence in the paddocks and a dizzying sum of one and threepence for a seat. However, just as his expected attendance at school hadn’t stopped him, nor did this minor inconvenience. Evading the attentions of policemen, club officials and pedantic fans who would have objected to having paid while he watched for free, Nat shinned up a drainpipe and clambered on to one of the lower sections of corrugated roofing before dropping down to join the crowd.

At this point, so embroiled in the game was Nat that even the dourest of 0-0 stalemates would have been unlikely to dim his enthusiasm as he first laid eyes on the mighty ‘Whites’, about whom he’d heard so much in the Brandwood schoolyard and on the street. As it was, he witnessed an exciting, pulsating encounter, albeit one that saw the Wanderers eventually succumb to a 4-2 scoreline. As well as representing the watershed moment of the young Lofthouse’s first time seeing the club that he would eventually become synonymous with (and it him), Nat also had the delight of seeing the team’s electric winger Ray Westwood score one of his 144 goals for the club.

Nat idolised the hard-heading Tommy Lawton, but the fact that Lawton would never play for Bolton excluded him from the very highest levels of hero worship (although Nat would occasionally make the relatively short trip to Liverpool to watch Lawton in the flesh from the terraces at Everton’s Goodison Park). Ray Westwood, on the other hand, fit the criteria of schoolboy icon perfectly. Though a native of Brierley Hill in Staffordshire, Westwood had been with the club since the age of 16, graduating through the ranks to become the undisputed star of the early 1930s team. An outside left who later moved inside, Westwood was, along with centre forward Jack Milsom, one of the goal-scoring heirs apparent of FA Cup-winning heroes from the 1920s, David Jack and Joe Smith. Westwood was not just an outstanding attacking threat but an entertainer, delighting in not just beating defenders but humiliating them with a dazzling array of skills. ‘He was an idol of mine,’ Nat would recall decades later. ‘A brilliant player, who knew he was a good player, but wasn’t big-headed. Over ten, fifteen, twenty yards he was electric. He mesmerised me as a boy, and I wanted to be like him.’ Even before he was ten, Nat’s dream of emulating his hero appeared unlikely, with his stocky build already resembling that of his father and making him ill-suited for the wide role typically occupied by lithe, speedy players.

Not only did Westwood live out the dreams of the town’s boys on the pitch, but off it he gave them a tantalising glimpse of the status, glamour and luxury that being a footballer could afford a young man. Long before the age of astronomical wages, Westwood was a rare example of a bona fide celebrity footballer, a regular at popular Bolton night spots such as the Palais de Danse and appearing in advertisements for Brylcreem. Nat’s most vivid memory of Westwood’s embodiment of this side of footballing life came one Friday at the ODEON picture house. Before the feature began, it was announced that Westwood had overcome an injury and would be playing the next day. The crowd’s reaction bordered on hysteria.

It was in his last year at Brandwood, 1936, that Nat’s hours of practising with Tom and the other kids on the street first began to bear fruit, albeit in a somewhat inauspicious and unexpected manner – a ‘sheer accident’, in fact. Tom, then at Castle Hill senior school, had broken into the school’s team as a centre half, thanks in no small part to Nat’s insistence on playing as a centre forward (if he couldn’t be a winger like Westwood, he could at least score as many goals as him!) and thus needing a natural foil. Not wanting to test his luck by risking the ire of paying patrons at Burnden too regularly by sneaking into matches, Nat sated his passion for the game by watching the older boys – including Tom – pit themselves against the teams from schools in the local area. While taken seriously by the players and schoolmasters alike, team selection was inevitably ruled by fairness and other extracurricular activities taking priority. Such was the case when, one day, Castle Hill found themselves without a goalkeeper. The teacher in charge of the team had no doubt registered Nat’s enthusiastic and consistent support of his brother from the sidelines, and seeing no other option, recruited the youngster as the team’s custodian.

Immediately, Nat was faced with a dilemma. On his feet were a pair of brand new patent leather school shoes – a substantial expense for the Lofthouse family even with a recent promotion for Dick to the role of the Bolton Corporation’s head horsekeeper allaying some of their financial fears. Well aware of Nat’s fanatical penchant for football, his mother Sarah had implored him not to ‘kick holes’ in the shoes, at the very least not on their first day of wear. However, despite not being one to go against the word of his parents, the pull of the pitch was too great. Nat took up his position between the posts against a school from Bury. Although just two years younger than the rest of the players, Nat was a fair shade shorter than the others, which was a notable disadvantage given his newly adopted position. The result – a 7-1 humbling – was hardly the most promising start to a career in organised football, but at least it quickly ruled out the possibility of Nat playing anywhere but outfield. To add insult to injury, the state of Nat’s brand new school shoes after the match earned him a scolding from Sarah when he returned home. ‘I’ve a hunch that when she left me and went back to her kitchen, Mother permitted herself a smile,’ Nat later said. ‘She knew I couldn’t resist kicking whether it was a stone, tin can, or ball in the street. Kicking was as natural to me as it is to a mule.’ Even such a chastening margin of defeat did nothing to dampen Nat’s endeavour; instead, it merely steeled his resolve to show what he could truly do.

In 1937, just after his 12th birthday, Nat joined brother Tom and followed in the footsteps of Tommy Lawton,2 now playing for Everton (where he’d been signed as a replacement for the club’s legendary striker Dixie Dean), in attending Castle Hill. Despite his baptism of fire the year before, his brother’s ability and glowing reports of Nat’s talent saw the younger Lofthouse given an immediate trial for the school team by the coach, schoolmaster Willy Hardy. By the end of the school year, he was a fixture in the side that competed on two fronts annually, for the Morris Shield and the Stanley Shield. This formal acknowledgement of his skills served only to further his devotion to playing, and saw him consciously begin to practise rather than simply playing whenever he could. Nat’s hours of relentlessly drilling himself, even without instruction, helped him develop basic ball control and passing skills, while watching the ball clip and spin off the cobbles gave him an appreciation for the importance of anticipation. And of course, wanting to be like Ray Westwood meant his shooting skills received an awful lot of practice.

Nat’s form for Castle Hill quickly led to him becoming the team’s first-choice centre forward, with him reflecting later, ‘I suppose I didn’t have the brain to be an inside forward or a wing half. We had boys who could win the ball, boys who could use it, boys who could beat a man and cross it … and me in the middle. Scoring was always important to me.’ Already in ownership of the relentless determination that would enable him to bulldoze First Division defences in the future, he began immediately scoring goals regularly and catching the eye of spectators. One such onlooker was Bert Cole, a friend of Nat’s father and an amateur coach who ‘got a great kick out of helping schoolboy footballers make the grade’. With Dick’s lack of interest in the sport, Nat had had few formal mentors, and Cole’s impact upon his game was profound. Cole had known Lawton at a similar age and possibly coached him, and he introduced Nat and Tom to a regime that involved practising shooting and heading against the wall of the stables that adjoined the family home. While monotonous and physically exhausting, Cole’s enthusiasm kept the Sunday morning exercise interesting, and the repetitive act not only honed Nat’s abilities (he later confirmed that ‘this form of practice was the basis of the heading technique I later developed with Bolton’) but also further impressed upon him the principles of hard work and application that his parents had instilled in him.

Cole wasn’t the only one to have noticed Nat’s obvious natural abilities. By the end of 1937, Nat received a call up to the Bolton Schools team, with his first game to be against the equivalent team from nearby Bury. Although he needed very little motivation to go out and show what he could do in the biggest match yet of his fledgling football life, Cole promised Nat a brand new bike if he was able to score a hat-trick. Despite his exemplary form for Castle Hill, this would be no mean feat. Nat would now be playing against a carefully selected group of players rather than a cobbled together school team. Quite what Cole’s motivation for making such a deal was, we will never know. He may have done so in the belief that he would be giving Nat an added incentive without truly risking having to shell out for the bike, or he may have had faith that Nat would be able to net three goals and deserved a reward for his efforts. The fact he volunteered so much time in nurturing Nat’s abilities suggests the latter is more likely than the former. As it transpired, Nat could count himself unfortunate not to have checked prior to the game whether the bargain extended beyond a mere hat-trick. Bolton ran out 7-1 winners, and Nat scored all seven. Though the Bury team were of a higher quality than those found competing in the school league, Nat’s precision in striking for goal, allied with the power of both his shots and his style of play in general were far beyond what was typically expected of players of his age. The similarities between Nat’s all-round skill and powerhouse tendencies and those possessed by Lawton were lost on none of the onlookers that day.