Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polaris

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

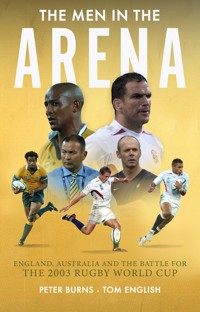

The ultimate World Cup showdown, in the words of those who were there. Shortlisted for the Sports Book Awards Rugby Book of the Year. From 1997 to 2003 England and Australia battled for domination of the rugby world in one of the greatest rivalries the sport has ever known. In The Men in the Arena, William Hill shortlisted authors Peter Burns and Tom English explore every aspect of the teams' journey to the 2003 Rugby World Cup final, telling the story primarily in the words of the protagonists at the centre of the battle. Featuring exclusive new interviews with players and coaches from both teams plus an array of superstars who faced them from New Zealand, Ireland, France, Wales and beyond, this is the inside story like it has never been told before. 'A splendid re-telling of English rugby's most celebrated story. Cracking stuff from start to finish' - Robert Kiston, The Guardian

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 679

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

POLARIS PUBLISHING LTDc/o Aberdein Considine2nd Floor, Elder HouseMultrees WalkEdinburghEH1 3DX

www.polarispublishing.com

Text copyright © Peter Burns and Tom English, 2023

ISBN: 9781915359155eBook ISBN: 9781915359162

The right of Peter Burns and Tom English to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The views expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions or policies of Polaris Publishing Ltd (Company No. SC401508) (Polaris), nor those of any persons, organisations or commercial partners connected with the same (Connected Persons). Any opinions, advice, statements, services, offers, or other information or content expressed by third parties are not those of Polaris or any Connected Persons but those of the third parties. For the avoidance of doubt, neither Polaris nor any Connected Persons assume any responsibility or duty of care whether contractual, delictual or on any other basis towards any person in respect of any such matter and accept no liability for any loss or damage caused by any such matter in this book.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, EdinburghPrinted in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

CONTENTS_______

AUTHORS’ NOTE

CAST OF CHARACTERS

PROLOGUE: IN THE MORNING, I WATCHED SCARFACE

ONE: THE GROWING PAINS OF CLIVE WOODWARD

TWO: THE MISFITS

THREE: EDDIE’S STORY

FOUR: IT WAS HUMILIATION, PURE HUMILIATION

FIVE: SLIDING DOORS

SIX: THE WORLD IS WATCHING

SEVEN: TRAGEDY

EIGHT: SUPERHEROES

NINE: CLIVE BEGINS TO STIR

TEN: JASON ROBINSON’S STORY

ELEVEN: LION TAMER

TWELVE: COMETH THE MIDGET

THIRTEEN: BACKY’S A STRANGE CAT

FOURTEEN: THE SERGE BETSEN EFFECT

FIFTEEN: BIG DEL HITS TOWN

SIXTEEN: MAT ROGERS’ STORY

SEVENTEEN: THE CROWN SLIPS

EIGHTEEN: HOW THE HELL DID I DO THAT?

NINETEEN: TREVOR WOODMAN’ STORY

TWENTY: WHAT GREAT TEAMS ARE MADE OF

TWENTY-ONE: CORNÉ KRIGE’S TEARS

TWENTY-TWO: THE POWER AND THE GLORY

TWENTY-THREE: THE CAKE TIN

TWENTY-FOUR: ROCKS IN HIS HEAD

TWENTY-FIVE: ARNHEM LAND

TWENTY-SIX: BRENDAN CANNON’S STORY

TWENTY-SEVEN: CHOSEN MEN

TWENTY-EIGHT: THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH

TWENTY-NINE: AND THEN THERE WERE FOUR

THIRTY: THEY THINK THEY OWN RUGBY

THIRTY-ONE: WHEN JONNY MET FREDDIE

THIRTY-TWO: DAD’S ARMY

THIRTY-THREE: THE FIRST HALF

THIRTY-FOUR: THE SECOND HALF

THIRTY-FIVE: EXTRA TIME

THIRTY-SIX: AFTERLIFE

THIRTY-SEVEN: THE COST OF THESE DREAMS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

England unveil their new coach in September 1997. From left to right: Roger Uttley, Bill Beaumont, Clive Woodward, Fran Cotton and John Mitchell. ‘I was shitting myself,’ admits Woodward. Getty Images

Eddie Jones in 1998, shortly after taking over from Rod Macqueen at the Brumbies. ‘I had no real coaching record.’ Alamy

Lawrence Dallaglio in action against John Eales’ Australia in 1997, his first match as England captain and the first Test of a brutal autumn. ‘We realised then that we were on a journey.’ Alamy

The original misfits: Joe Roff, Stephen Larkham, Owen Finegan, George Gregan and David Giffin at a Brumbies pre-season photocall. ‘We were dismissed as a group of rejects,’ says Gregan. Gary Schafer

Jonny Wilkinson in his first Test start at No.10 in the 1998 Tour of Hell opener against Australia in Brisbane. ‘I was on the phone crying to my mum and dad for three days after that game.’ Getty Images

Pieter Rossouw is scythed down by Neil Back at Twickenham in November 1998. The back-row trio of Dallaglio, Back and Richard Hill were a cosmic force in a famous England victory over the world champions. Alamy

Jonah Lomu repeats his 1995 World Cup demolition of England with another brutal performance in the 1999 group game that consigned England to a play-off match just three days before a quarter-final against South Africa. FotoSport

Jannie de Beer kicks one of his five drop-goals that sent England out of the 1999 World Cup. He said in the aftermath that he had felt touched by God that day. Getty Images

Stephen Larkham sends over his match-winning drop-goal against South Africa in the ’99 semi-final. ‘He did it on the run, with a dodgy knee, and his eyesight isn’t very good,’ said John Eales. Getty Images

The world champion Wallabies celebrate their victory over France in the final. ‘No one would have said two years before that we were going to be the ones lifting this trophy,’ said Eales. Inpho Photography

In a momentous year for rugby in both codes in Australia, the Wallabies backed up their World Cup victory by winning the 2000 Tri Nations (above), while the Kangaroos lifted the rugby league World Cup with Wendell Sailor (below left) and Mat Rogers (below inset) announcing themselves as superstars of the game. AllSport & Alamy

The moment many have marked as the true turning point in England’s fortunes during the Woodward years: the team celebrate beating South Africa in Pretoria in the summer of 2000 thanks, in part, to Jonny’s discovery of the drop-kick in his armoury. ‘I had this lightbulb moment,’ he recalls. Corbis

It takes twenty seconds to score. With the clock ticking deep into injury time against the Wallabies at Twickenham in November 2000, Iain Balshaw chips to the corner and Dan Luger gains enough downward pressure to score the winning try. ‘He bounced it,’ says Phil Waugh. Getty Images

Jason Robinson shows the Twickenham crowd just how electric he is after coming off the bench against Scotland in 2001. ‘Jason just took us to a new level,’ says Woodward. Getty Images

The Brumbies lift their first Super Rugby trophy. ‘Eddie is hard but he’s very deliberate and he gets results,’ says George Gregan. ‘Not many champions get there by taking short cuts. Unfortunately, you have to hit the hurt locker.’ Getty Images

The Lion Tamer. Justin Harrison celebrates with Elton Flatley as the Wallabies clinch the third Test – and the series – against the 2001 Lions. Getty Images

After his success with the Brumbies, Eddie made the step-up to take charge of the Wallabies for the 2001 Tri Nations. ‘I think everyone was fearful of him,’ remembers Brendan Cannon. Getty Images

Ben Cohen makes a break against New Zealand at Twickenham in November 2002 and flies in to score as England go on to record a famous 31–28 victory. ‘If you look back on those tries I scored around that time you’ll see I didn’t really show any happiness,’ he recalls. ‘I’d score then often slam the ball down on the ground. It was all fury.’ Getty Images

Having been in the Test wilderness for two years, Josh Lewsey returns to the England fold in dramatic fashion against Italy at Twickenham in the 2003 Six Nations and shakes up the back-three options available to Woodward just months before the World Cup. FotoSport

Jonny Wilkinson hammers Justin Bishop during the 2003 Grand Slam decider. ‘He was magnificent,’ said Greenwood of his fly-half’s performance. FotoSport

Captain fantastic. Martin Johnson powers into space against the All Blacks in Wellington in the summer of 2003 as England record a famous win against the odds, playing with just thirteen men at one stage. Getty Images

A large saltwater crocodile moves towards the flat-bottomed boat carrying Wallabies on their river cruise in Arnhem Land. ARU

In the opening game of the 2003 World Cup, Big Del dots down against Argentina. ‘I don’t pray too much, but every now and then I ask to speak to my old man. Before we played Argentina, I told him I was going to score a try for him and it happened.’ Welloffside

Will Greenwood, the man Woodward described as ‘the best player I have ever seen play in the centre for England’, scores in the crucial pool game against South Africa. With all his troubles at home it was a remarkable performance. ‘If you watch the replays you can see a smile on my face,’ said Greenwood, ‘because for a short time rugby had pushed the worry from my mind. There are not many jobs you can say that about.’ Getty Images

Lote Tuqiri fights to get away from the covering Irish defence in the Wallabies’ crucial pool game. Welloffside

‘Too old?’ Neil Back asked when questioned about the Dad’s Army moniker. ‘You’re either good enough or you’re not. If people say you’re not good enough, then fair enough. But too old? That doesn’t mean anything.’ He proves his point as part of a magnificent England performance against France in the semi-final of the World Cup. Welloffside

Stirling Mortlock sprints away to score against the All Blacks in the semi-final. When I hit the twenty-two and realised they weren’t going to get me, I screamed out. You can’t really tell from the footage because my mouth’s open, but I’m just hollering out as I run.’ Getty Images

A tale of two tries. Lote Tuqiri rises above Jason Robinson to score for Australia, before Robinson scorches the earth to score for England. Getty Images

A kick that reverberated around the world. ‘Was it a great moment?’ says Jonny. ‘I don’t really understand. I sometimes wish I hadn’t been on the field so I could have understood the gravity of what it meant.’ Getty Images

Jeremy Paul with the injured Ben Darwin at the end of the final. ‘He could have been one of the best tighthead props ever,’ says Paul. ‘He’s a beautiful human being, Benny.’ Getty Images

Good night, sweet prince. Jonny leaves the field, his life never to be the same again. ‘Was it worth it? You know, that’s actually quite a difficult question to answer.’ Getty Images

For Julie, Isla, Hector, Rory and Phoebe, always.PB

To Lynn, Eilidh and Tom, with love.TE

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

AUTHORS’ NOTE

When planning this book we had an epiphany. Having watched The Last Dance on Netflix, we wondered if there might be some value in emulating the format: we would substitute Martin Johnson for Michael Jordan and give him a stake in the project, let him help to shape it. We proposed the idea to Johnno and he liked it. But then a few days later he emailed to say that he had some reservations and he’d like to chat it over. We arranged a Zoom.

‘Listen,’ he said, ‘I loved your ’97 book’ – we had recently published This is Your Everest about the 1997 Lions in South Africa – ‘and the best thing about it is how honest everyone you spoke to is. Now, for this project, if the guys know I’m officially involved, maybe they won’t be so honest. If anyone thought I was an arsehole, I want them to say it.’

‘Did he say that?’ asked Will Greenwood when he was told this story. He cracked a wry grin. ‘In which case: Johnno’s an arsehole.’

Self-awareness has never been an issue for Johnno. Nor does he have a sense of grandeur about who he is or what he has achieved. This vignette sums him up as well as any.

‘What I really want to know,’ continued Johnno, ‘is what guys like Trevor Woodman have to say. Guys that don’t normally get the spotlight. I went to an event a while ago and Trevor was speaking. I could have listened to him all night.’

‘We’ll try and track him down,’ we said. ‘Anyone else?’

‘Backy.’ Then he laughed.

‘Why are you laughing?’

‘Because Backy . . . well, you’ll understand once you get into it. Backy’s Backy. He’s different. Very different. I’ll enjoy hearing what you make of him.’

They’re all different and that’s what made this project so irresistible. And we haven’t even touched on the Aussies yet – or other members of opposition teams who feature in the pages that follow. The cast of characters is extraordinary, their lives so unique and yet they are bound by the thread of their international careers. This story is just window on their lives. But what a story it is.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

featuring

FROM AUSTRALIA

Eddie Jones: Head coach. ‘I didn’t have any athletic gifts, so I became a competitor. I fought. You’ve got to find some other ways of being in the game.’

Mat Rogers: Fullback. Son of a rugby league legend. ‘He was my hero – he was every kid’s hero back then. He’d just get swarmed by people. I’d stand there in awe at how adored he was.’

Wendell Sailor: Wing. Fast, powerful, the life and soul of the party. The gregariousness hides deep scar tissue. ‘You can call me Wendell, Big Del, the People’s Champion, whatever you like, mate.’

Stirling Mortlock: Centre. Terminator. Scary in attack and defence. ‘I was on the boat when the crocodile nearly ate half our team.’

Elton Flatley: Centre. Deadly with the boot. ‘You know you’re a kicker when you start enjoying those pressure moments.’

Lote Tuqiri: Wing. Born in Korolevu, Fiji. Iconic rugby league star who switched to union. ‘There was a fair bit of racism. I copped it. It got my back up, I’ve gotta say. It gave me a bit of a fire.’

Stephen Larkham: Fly-half. Introvert. Rugby genius. Nicknamed ‘Bernie’ after the corpse in Weekend at Bernie’s. ‘It was 6.30, only an hour-and-a-half before the game and we’re all standing around fighting to hold back tears.’

George Gregan: Scrum-half. Captain. Best No.9 in the world. ‘I had a beer with Eddie Jones. He said, “Mate, we’re going to change the way rugby is played.”’

Bill Young: Prop. Underestimated but wily. ‘If you’d told me I would play forty-six Tests for the Wallabies, I’d have been delirious.’

Brendan Cannon: Hooker. Lucky to be alive after a near fatal car crash in his teens. ‘I woke up with ambulance and firemen around me. It took them ninety minutes to cut me out. I got taught about the fragility of life that day.’

Al Baxter: Prop. An architect chasing a dream. ‘The reason I liked rugby was whacking into people – and as a front-rower your job is whacking into people.’

Justin Harrison: Second row. Nicknamed Goog because in Australia a googy egg is a bad egg. Handy with his fists. ‘I was brought up in the Northern Territories, so the sport of staying alive was all I really played up there.’

Nathan Sharpe: Second row. A giant at 6ft 8in. ‘When I made my debut for Queensland I was just so scared of letting down the guys. I didn’t want them to say, “Who’s this young guy? He’s not up to it.” I pretty much approached my whole career that way.’

George Smith: Blindside flanker. King of the breakdown. ‘Eddie Jones recognised early that I played a different game to other back rowers. I was one of his favourites.’

Phil Waugh: Openside flanker. Dynamo. His teammates think he’s slightly psychotic. ‘It was just a willingness to work. Nothing can replace hard-work.’

David Lyons: No.8. A farmer’s boy. The power in the Wallaby back row. ‘I grew up in the bush, working with my old man. It’s good for kids to start work early. It was a great childhood.’

Jeremy Paul: Hooker. World Cup winner in 1999. A Maori who moved to Australia at thirteen: ‘Dad worked in freezing works and abattoirs all his life. Mum, same thing. Blue-collar workers.’

Matt Dunning: Prop. Wide-eyed and callow. ‘I wasn’t actually allowed to play rugby until I was twelve because Mum was worried I’d get injured.’

Matt Cockbain: Second row. World Cup winner four years earlier. Enforcer. ‘You each had a job in the team and my job was to try and hurt as many people – legally – as I could.’

Matt Giteau: Centre. World-class tyro. ‘I grew up playing rugby league. I didn’t enjoy union for the first couple of years, couldn’t understand it.’

Joe Roff: Wing. Prodigious try-scorer. A World Cup winner in 1999. ‘You talk to most of the players from that period and they’ll say Eddie Jones was the best coach they ever had.’

FROM ENGLAND

Clive Woodward: Head coach. Will let nothing stand in the way of his ambition. ‘I was probably more surprised than anyone when they chose me. I was shitting myself.’

Josh Lewsey: Fullback. Former military man. Calm under pressure. Ruthlessly competitive. ‘Leaving the army was the hardest decision I ever made.’

Jason Robinson: Wing. Fastest feet in the game. Born-again Christian desperate to move on from his troubled past. ‘The way I saw it, if I didn’t know where I was going, the opposition certainly didn’t know where I was going.’

Mike Tindall: Centre. A tank. Central to the England midfield defence. ‘I said to Mortlock, “Fuck me, mate, you better play well today because I’m going to be fucking awesome.”’

Will Greenwood: One of the best centres in the world. Has experienced the tragic loss of his baby son. ‘Freddie was alive for just under an hour. It was rugby that allowed me an escapism, that brought me out of that.’

Ben Cohen: Wing. Prodigious try-scorer. Haunted by the death of his father. Nephew of a famous England World Cup winner. ‘It’s weird when you look back on it, the parallels that exist with 1966 when my uncle George won the World Cup.’

Jonny Wilkinson: Fly-half. Young superstar with the world at his feet and the weight of a nation on his shoulders. ‘Am I happy? Happiness is a bit of a destination. I like to see the question more as: “Am I grateful to be alive?”’

Matt Dawson: Scrum-half. Perfect foil to his fly-half. ‘When anybody plays against England, it’s the biggest game they’re ever going to play. It’s an unarguable fact. I know there’s an element of arrogance around that, but in the same breath, fucking get over it.’

Trevor Woodman: Prop. A late-comer from Cornwall. Dynamic and powerful. ‘Two days after my first start, I injured my neck. The disc completely ruptured which meant I needed surgery. I rehabbed with a guy called Don Gatherer, doing all kinds of stuff that other people weren’t doing. I went there three times a week for twelve weeks, a three-hour round trip – all these things you do to try to keep your dream alive.’

Steve Thompson: Hooker. Converted flanker. Immensely powerful. Difficult past and upsetting present. Has spoken powerfully about his battle with dementia. ‘I don’t know how long I have. Some people go ten, fifteen years with it, maybe more.’

Phil Vickery: Prop. The Raging Bull. Humble Cornish roots. The best tight-head in the world. ‘Myself and Trev and Thommo got together, said our little bits, banged our heads together. “Let’s go do it for each other and for everyone else. We’re going to get one chance at it.”’

Martin Johnson: Second row. Captain. Legend. ‘When you’re winning, everyone’s fantastic. Bit of pressure? That’s when you find out what you’re about.’

Ben Kay: Second row. Fast and athletic, he has fought off serious contenders to partner Johnson. The big brain of the England pack. ‘We were convinced the Aussies were spying on us.’

Richard Hill: Blindside flanker. A quiet assassin. ‘By 2001 we’d established that Hill–Dallaglio–Back partnership and were starting to think as a unit. We could read each other’s games perfectly.’

Neil Back: Openside flanker. A fitness fanatic. Some say he’s too old. ‘Too old? You’re either good enough or you’re not. If people say you’re not good enough, then fair enough. But too old? That doesn’t mean anything.’

Lawrence Dallaglio: No.8. Lantern-jawed, half-Italian, half-Irish heartbeat of the pack. ‘It was carnage. No one could speak. Players were sprawled on the floor, others were vomiting in the bins, I was retching.’

Jason Leonard: Prop. Veteran of the 1991, 1995 and 1999 World Cups. World-class operator on the field, hollow-legged centre of the party off it. ‘You learn to deal with different referees in different ways. André Watson was a “Yes, sir”, “No, sir”, “Three bags full, sir” kind of guy. Whatever André said was right.’

Lewis Moody: Flanker. The Mad Dog. Bundle of energy, willing (indeed, happy) to stick his head where others would fear to tread. ‘People look at the England and Leicester teams I played for and say, “Oh, it must have been amazing playing with best mates.” But there were plenty of guys in those sides that, actually, I didn’t like at all. But I respected them.’

Mike Catt: Fly-half-cum-centre. South African-born playmaker capable of unlocking defences with slick hands, clever kicks and incisive running lines. ‘There were no excuses.’

Iain Balshaw: Wing-cum-fullback. Greased lightning. ‘All the work we put in was epitomised at full time when Johnno got us into the circle and said, “We all know what we need to do, so just go out and do it.”’

PROLOGUE

IN THE MORNING, I WATCHED SCARFACE

On the Thursday before the World Cup final, Martin Johnson went to the Sydney aquarium on the eastern side of Darling Harbour, to the north of the Pyrmont Bridge. He was there with his wife, Kay, and their baby daughter, Molly. Johnno pushed a stroller past the tropical fish displays, through the shark tanks and into the Great Barrier Reef Complex with its coral caves and its touch pools and its vast Oceanarium.

The way Johnno saw it, this was an attempt at down-time in the midst of the most momentous week in the history of the England rugby team, a team he captained. He knew that unprecedented levels of stress were coming down the track but Saturday night at eight o’clock was when he needed to be ready, not now. ‘I remember Will Greenwood saying to me, “I’ve got a mate who’s rung me and said, ‘I’ve just seen Johnno at the aquarium with his missus and his kid! What’s he doing? What’s he’s thinking?’”’

‘I’ll tell you what he’s thinking,’ said Johnno. ‘He’s thinking: it’s a day off and he’s trying not to think about rugby. He’s not not thinking about rugby because it’s in his head and he knows he’s got the biggest game of his life coming up in two days, but he’s trying to keep himself down. Friday you train and you come back up a bit, but you have to try and keep a lid on it until Saturday night.’

Everybody counted the days to the final in different ways. As Johnno was looking at fish, Trevor Woodman was eating roast lamb in a friend’s penthouse apartment overlooking the water in Manly. Greenwood, Ben Cohen, Steve Thompson and Lewis Moody had formed a cinema club and every Friday went to watch a movie, the Friday before the World Cup final being no exception. Out the hotel in Manly, turn right, down the road a little bit, another right and there you’d find them. Thompson would buy a 20kg tub of pick and mix and they’d dish it out between them. That was their routine.

Lewis Moody: The night before the final, New Zealand were playing France in the third-fourth play-off which meant no one was in the cinema, everyone was out watching the game, and the guy behind the desk was like, ‘Sorry, we can’t put the movie on, we’ve cut the film up.’ And we were like, ‘What do you mean he’s cut the film up? No, you can’t do that, we’ve got the World Cup final tomorrow, our routine is to watch a movie the night before every game, you don’t understand how important this is.’ So he told us to go and speak to the projectionist, who was this student who was splicing the film up. And he said, ‘Ah, lads, I’m going to meet my mates, I’ve got a night out.’ And we said, ‘Look, what is it going to take?’ I think we ended up paying $500, which would have given him the best night ever as a student, but it meant that the cinema club got to watch School of Rock and keep our routine in place.

Jonny Wilkinson: Did I go to the aquarium? The cinema? There’s no chance. Absolutely no chance. I mean, the idea that I would be able to focus on a film? You’ve got to be kidding me.

Lawrence Dallaglio: Jonny Wilkinson, bless him. You felt like he had the world on his shoulders. Because he probably did. He was playing fly-half for England and he was just at a different stage of his career, he had a lot of pressure. I remember walking down the beach with my wife, not far from Manly, and I said, ‘Come on, let’s go out for lunch.’ And walking in the other direction was Jonny – in full disguise. He pretty much had a balaclava on and you wouldn’t have recognised it was him. He just didn’t want to be recognised. And I thought to myself, ‘God, poor guy, he’s getting ready for the final and he just looks so intense.’ I felt for him.

Jonny Wilkinson: I was working with a newspaper and they wanted to do a bit of a feature before the final, take a picture of me somewhere and do an interview. It was like an undercover mission. I sneaked out of the hotel in the back of a car, getting down low in the back seat. We got to the beach, I sprinted down to a corner where no one could see me, took my hat and sunglasses off, took the picture and then got out of there. It wasn’t that it was a dangerous scenario, it was to do with what was going on inside me – I was completely overwhelmed by the perception that it was dangerous. That’s the state I was in.

Martin Johnson: Jonny couldn’t unwind. He could not unwind. And he said so himself: ‘The older boys know how to switch on and off, I don’t.’ The thing people don’t realise is that you’ve got to be down more than you’ve got to be up. If you want to be hitting the very top level, you can’t be up there the whole time. You’re up there when you need to be up there – which is kick-off. You have little peaks all the way to kick-off. People don’t realise how important it is to try and get away from that and be as normal as possible. But Jonny couldn’t do it. We had a team meal on the Wednesday of final week and he didn’t come. He just couldn’t do it.

Jonny Wilkinson: I can’t remember that much about the inner workings of the week. When you said there was a dinner out, as soon as you said that I thought, ‘I probably didn’t go.’ I was really challenged. I was definitely out of my comfort zone. I’m not a big social animal at the best of times but especially not when I had games coming up and there was business to be done. I spent the week thinking about the game constantly, non-stop trouble-shooting, training, kicking, and trying to distract myself. I would be very different now, I understand performance much better now, but according to how I was back then, that was the best I had. It was fatiguing going through that nervous preparation.

All I could ever think of was the fear and the panic – and then you add in my mechanism for handling that, which was going out and seeking reassurance by kicking more balls, looking at more video, doing more gym sessions, doing extra running. With the exception of the first pre-season game of a season, I never once went into a game during my career feeling fresh. The fatiguing element was crazy. I look back now and I give myself a pat on the back for sometimes even making it out on the field.

Trevor Woodman: Me and Phil Vickery were sitting there on the Friday going, ‘I can’t believe we’re about to play in a World Cup final. That’s some journey we’ve done from Plymouth Albion to here.’ You try to downplay the significance of it to keep yourself calm, but it’s pretty hard.

Ben Cohen: My uncle George was staying in Manly and the night before the final he came to see some of the team. He talked about his World Cup final in 1966 and what was interesting was that he said, ‘You can play a game of rugby every week and it will mean nothing in your life, you’ll move on and forget it. But if you win this game tomorrow, it will change your life forever.’

Will Greenwood: I watched Scarface the morning of the final. Then I went back to bed, just trying to sleep through the hours. Rest, rest, rest, rest, rest. There’s a real deviation of emotions during the week. Loving it, feeling relaxed, smiling, then Wednesday, Thursday, Friday: ‘My God, what am I doing? I want to go back to the City, I want to trade futures. That’s what I’m good at. I like maths. I’m a skinny bloke, they’re going to kill me. Have you seen the size of Stirling Mortlock? Everyone’s better than me. I’m rubbish. I’m going to be an epic fail.’ Then I get to the team room and I’m ready to go.

It was a one hour and twenty-minute drive from the Manly Pacific hotel to Stadium Australia. Rain was falling. Not heavily, but it would get worse. Watery light bathed the England team and backroom staff as the coach wended its way through Sydney’s rush-hour traffic for their date with destiny: the Rugby World Cup final against Australia.

Twenty-two players were trying to keep a lid on their nerves. Twenty-two players, an army of backroom staff and a nation holding its breath. But there were ghosts on the bus, too: all the mishaps that had dogged England for years – embarrassed by Wales at the inaugural World Cup in 1987, they had been hosts of the 1991 tournament and should have beaten the Aussies in the final at Twickenham, but they hamstrung themselves with a baffling game plan and lost by six points. In 1995 they were Five Nations Grand Slam holders but they were humiliated by New Zealand in the semi-final. In 1999 they were drop-kicked into the dust by South Africa at the quarter-final stage. They had come close to Grand Slams in 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001 and 2002. But they always fell down somewhere along the way. One game each campaign where it all went wrong. And don’t even mention the Tour of Hell . . .

But they looked different beasts now. The Grand Slam had, at last, been secured with a tumultuous thumping of the Irish in Dublin. They were the number one-ranked team on the planet, they hadn’t lost to a southern hemisphere team in years. They had gone to South Africa, New Zealand and Australia and won. They were a thrilling side to watch – fast, skilful, brutal, clinical, a team hardened through experience.

Clive Woodward: On the bus, I always sat on my own, first row on the left. I didn’t want to talk, just think. Talking at that stage was largely superfluous.

Martin Johnson: Your nerves are at you and there’s a lot going on in your head. When you arrive at the ground you look across at all the people enjoying themselves outside and you think, ‘I wish I was there with them.’

Will Greenwood: I felt physically sick.

Jonny Wilkinson: I always quite enjoyed the bus trips. For some reason I found it a nice space of reflection for me. It wasn’t as intense as sitting in a hotel. I enjoyed the distraction of being around the boys and looking out the window. I was crossing that line getting ready to go. It helped push me into the mental space I needed to be in. The music always helped. But I’ll always remember this from that bus trip to the final – someone cocked the music up. We usually always finished up with Eminem’s ‘Lose Yourself’ but as we were heading in towards the ground that finished and ‘Rock the Casbah’ came on. We were all sat there and it was one of those moments when everyone probably wanted to look at each other and say, ‘Uh, what the hell’s going on here?’ But no one wanted to break that focus, so everyone just sat there trying to ignore what was playing. I’m laughing now thinking back to it.

Clive Woodward: You get ready and you’ve just got to think about your own performance and the whole team thing. If you do that, you’re fine. The moment you start thinking about the enormity of what we were trying to do, that’s when you don’t think correctly. That’s when it could all go pear-shaped.

Ben Cohen: By the time we got to the World Cup, we’d earned the right to be called the best team in the world. We ticked all the boxes. We had a mobile front row, a huge second row with a captain who had an aura about him, a perfectly balanced back row, fearless half-backs and a guy in Jonny Wilkinson who habitually won matches with his boot, an intelligent midfield and a potent back three.

Martin Johnson: Some guys liked the tub-thumping, some guys didn’t. I used to try and avoid looking at Richard Hill because he hated it. He’d roll his eyes and you could see him thinking, ‘Come on, Johnno, I get it.’ Mike Tindall would have his music on, dancing around. The front row would be gathered around each other, all serious. Everyone had their own way of getting ready.

Jonny Wilkinson: All I wanted was for someone to come along from two hours into the future and say, ‘It’s fine. You played fine. Your team was great. Nobody got hurt.’ I wanted the reassurance. But that person didn’t come. They never came.

Will Greenwood: If there’s five minutes of my career I’d like to relive, it would be the five minutes in the changing room before the final. Everyone getting ready, tunes pumping, lucky socks on, Johnno opposite me. I can close my eyes and tell you exactly where everyone was sat. Lol [Dallaglio] would be doing all the chatting, Backy would be like Bill Sykes’ little dog, just yamping, yamping, yamping. But there was almost like an invisible X in the middle of the floor and when Johnno stood in it there was a kind of gravitational pull and we’d all form a circle around him. He started to say something but then stopped. He looked around and just said, ‘You’re good.’ I’d love to be there again.

Martin Johnson: I didn’t say much. ‘Boys – we win games. That’s what we do. So let’s do what we do.’

Jonny Wilkinson: The changing room beforehand was both incredibly calm and incredibly tense, everybody going through their usual habits. Then came the warm-up in front of a packed house and the anthems. I remember the images, what everything looked like, but how I remember them is by recalling the senses – the sight, the sound, the smell, the feel of everything that happened.

Jason Robinson: I’d lost the rugby league World Cup final against Australia in 1995. That was a sore thing. When you play in those games there’s one winner and everyone else loses. I’d played in Grand Finals, played at Wembley, played Challenge Cups and all the rest of it – but suddenly those games felt like Under-10s in comparison. The world was watching. Oh, man.

Will Greenwood: Then the doors open and it’s down through the corridor and into the tunnel, where we lined up opposite the Aussies.

Neil Back: Whenever Johnno led the team out onto the pitch, whether it was for Leicester, England or the Lions, he’d stop at the head of the tunnel and say a few inspirational words. That night, he got to the head of the tunnel, about to lead us into that cauldron, he turned and looked at the players and didn’t say a word. Then he turned back and led us out onto the field. A couple of weeks later I asked why and he said, ‘I turned around and looked into everyone’s eyes and knew we were ready. I didn’t have to say anything.’

The nerves and the pressure were different but no less intense for the Wallabies. They were the reigning champions and they were playing at home. Their pedigree in the competition was unmatched. Of all the great rugby powers, they were the only ones to have won the World Cup twice. The heroes of 1991 – Nick Farr Jones, Michael Lynagh, Tim Horan, John Eales – had been followed into history by the class of ’99 with Eales as captain and Horan as the genius of the backline. That pair had now retired, but a strong core from 1999 were still playing in green and gold.

Since Eales had lifted the World Cup in Cardiff on 6 November 1999, George Gregan, Stephen Larkham, Joe Roff, David Giffin, Matt Cockbain and Jeremy Paul, who had played beside him, had swept all before them. Bledisloe Cups, a Lions series, Tri Nations titles, Super Rugby trophies – all had been claimed. An opportunity now lay before them to pick up an unprecedented third William Webb Ellis trophy.

The Wallabies’ great rivals, the fearsome All Blacks, had been overcome in the semi-final. Now only England stood between them and rugby immortality. The Wallabies, like England, were a fine balance of experience and youth, of granite and stardust.

Al Baxter: There was so much excitement, so many nerves. The adrenalin starting to kick in. A lot of the guys took sleeping tablets to help them get a good night’s rest.

Ben Darwin: On the day of the game, they normally get an old Wallaby legend to present the shirts before the team leaves the hotel, but they asked me to do it before the final. God, I was bawling. Greegs was bawling, the whole team was bawling.

There was a searing poignancy to Darwin being the one to hand out the jerseys. Born in Crewe in England but raised in the northern suburbs of Sydney, Darwin had been Australia’s first-choice tight-head prop, a twenty-seven-year-old with twenty-eight caps to his name, the best and the worst of them coming in the Wallabies’ momentous semi-final victory over the All Blacks seven days earlier.

Fifty minutes had been played. A scrum was called. Up against him, Kees Meeuws, the vastly experienced, barrel-chested tight-head from Auckland, fresh off the All Blacks’ bench.

Ben Darwin: Kees was very explosive and I was pretty dusty at that point. I’d had a knee clean-out earlier in the year and I was kind of rushed back so that I could play in the tournament. My inside leg was never the same after that operation and the way to scrummage someone like Kees is to scrum straight or scrum out, producing power off the inside leg – my left leg, which is the knee I’d busted. He came on and when he packed down to scrum he took me up and I got my head and my neck caught on Keven Mealamu [the All Black hooker]. Kees was underneath my sternum and basically I got kind of folded. I heard what sounded like a firecracker going off. It was the loudest crack you can possibly imagine. That was my neck dislocating. I then lost all feeling below my chin.

Darwin screamed out, ‘Neck, neck, neck!’ and to his eternal credit, Meeuws immediately reacted and stopped pushing. ‘Once I heard that “neck, neck” call, I didn’t go through,’ said Meeuws. ‘When someone says “neck”, they don’t call it out for nothing.’ The Kiwi says the incident was so harrowing he doesn’t like to talk about it all that much.

Ben Darwin: The physio came over and I said, ‘I can’t feel my arms and legs.’ At the moment it happened I was actually really calm. I didn’t go through the trauma until later. There was no pain. I couldn’t feel anything. I was looking at my hands going, ‘They’re not mine.’ The physios realised it wasn’t good and tried to get the neck brace on. That was the difficult part. It took eight minutes to get it on and then get me off the field.

The thing that I remember going through my head was: ‘I really like computers, I want to get into computing. If I’m going to be a quadriplegic, which I probably am, I’d like to do some study in computers.’ That was my way, I suppose, of trying to solve the problem of what I was going to do with the rest of my life.

The pain came later on. It was like my body was rebooting. It started with pins and needles and then got steadily more painful, but the important thing was that feeling was coming back. The doctor said, ‘When these things happen, they generally end in one of three ways: you’re killed, you’re left quadriplegic or you walk out of here. And you’re going to walk out of here.’ The enormity of what had happened didn’t really hit me until he said that. I was like, ‘Wow, things really could have been very different.’ Thankfully I’d regained movement within a couple of hours. But that was it, my rugby career was over.

That was the backdrop to Darwin presenting the jerseys, an intimate moment behind the scenes on the day of the final that nobody who was there will ever forget.

Al Baxter: You think you and your teammates are all bulletproof. It was only after the New Zealand game that we found out the full extent of what happened and how close Ben was to being killed. Seeing him at the hospital and speaking to him throughout the week, it really got to me.

George Gregan: I still get emotional thinking about what happened to Benny. I was there when he came down to Canberra to play for the Brumbies in 1997. That year, he went on the development tour and the following year he was part of the senior squad. He was a guy who had a Wallabies jumper stuck on his bedroom wall when he was fifteen and he worked and worked and worked until he got his own. When he came to hand out the jerseys I started to talk about Benny and suddenly this wave of emotion came over me. I wanted us to try and treat it like just another game but I was sobbing. Yeah, it was big.

Stephen Larkham: It was 6.30 p.m., only an hour-and-a-half before the game, and we’re all standing around fighting to hold back tears.

George Gregan: I said afterwards, ‘Boys, we’re going to have to rein it in a little now, we’ve still got a way to go before kick-off.’ But it was a special moment. We were playing for Benny. He’d worked his butt off to be in the team and what happened the week before was horrific, but he was still around the camp and it meant a lot. It was a special group and not everyone could get on the field, but everyone was part of it. I was very proud to be captaining that team.

Mat Rogers: Game day. Except it’s game night, so you deal with your nerves for roughly fourteen hours from wake-up to kick-off. We had a team walk in the morning and did a passing drill in a park then walked around Parramatta with cars blaring their horns and people shouting good luck. Arriving at Stadium Australia, you tell yourself to treat it like any other game, but you can’t because it’s not.

Al Baxter: There’s still nervousness and fear. ‘I don’t want to stuff up, I don’t want to be the reason we lose the cup, I don’t want to make a fool of the jersey or embarrass myself in front of my family and the country and all those people watching.’

George Gregan: You have to embrace it. Take a few deep breaths and focus and what you need to do once the time comes, don’t play the game in your head beforehand. Not to sound arrogant, but we’d worked exceptionally hard and we expected to be in that position. We didn’t go into that competition wanting to just be in the final or to defend our title – we wanted to go out and win it again. That was our attitude. And now that we’d got ourselves in that position we were only eighty minutes away from achieving our goal. We knew it was the last time that group was going to play together

Stirling Mortlock: The challenge was not getting too excited and losing all energy through emotion or anxiety. I’d managed to keep a lid on it for most of the time, so by then I was buzzing. I couldn’t wait to get off the bus. Could. Not. Wait.

A capacity crowd of 82,957 were packed into the Telstra Stadium. Twenty giant cylindrical figures representing each competing nation billowed around the periphery of the pitch. Each was a Cyclops, representing the one-eyed nature of each nation’s fans. One by one, the figures collapsed and were gathered away until just two remained behind each set of posts: the English and Australian Cyclops glaring menacingly at one another across the length of the pitch.

Mike Tindall: I’d convinced myself all week about the final and how you should approach it. And I’d gone, ‘Right, it’s the biggest game I’m ever going to play in, I want to enjoy it. I don’t want it to be one of those games where you sit around so worried about it that you end up playing shit because you’re too nervous to do anything. So I’m going to enjoy it. I’m going to be bouncing off the wall.’ And we pulled into the tunnel and we’re all lined up next to each other and you’ve got to run past the cup and everything. We hadn’t organised to line up next to our opposite number but, as it happened, Stirling Mortlock was standing opposite me. And I was jumping around, looked across at him and he was staring at a hole in the back of Lote Tuqiri’s head.

Stirling Mortlock: I had Lote in front of me and Will Greenwood and Tins both beside me. Tins was pretty similar to me – a bundle of energy, right? I was there looking dead ahead, dead ahead. And then I looked over at him.

Mike Tindall: And I said, ‘Fuck me, mate, you better play well today because I’m going to be fucking awesome.’ And he stared at me, and I thought, ‘Oh no . . . tunnel fight.’

Stirling Mortlock: I was thinking, ‘What am I going to say to that?’ Am I going to puff my chest out and square up to him? But I just couldn’t help it, I gave him a massive slap on the bum and said, ‘That’s what I’m fucking talking about.’ And Lote and Will and everyone around us started laughing, no one knew what to do. And then we started running out.

CHAPTER ONE

THE GROWING PAINS OF CLIVE WOODWARD

In late September 1997, Clive Woodward left his home in Maidenhead and set off for Twickenham for the first day of his new job as England’s head coach. At the stadium he was greeted by a receptionist, who didn’t recognise his name when he gave it and seemed to have no expectation of his arrival. When Don Rutherford, the president of the RFU, appeared he seemed equally perplexed by Woodward’s presence and even more bewildered when Woodward asked where his new office might be. Woodward demanded work space, a phone, a computer and a secretary. Poor old Don didn’t know what had hit him.

Woodward was a terrific player in his day, but coaching in the rarefied air of Test match rugby was alien to him. He’d done a bit with lowly Henley-on-Thames, then moved to London Irish, the England Under-21s, and had a short stint at Bath. The only headlines he’d made surrounded the eccentricity of his coaching, but players enjoyed him. Almost all of those who’d been coached by Woodward had stories to tell about some of his oddball thinking but also had an admiration for his passion and his intelligence. No one had seriously considered him as the successor to Jack Rowell – one of the most successful coaches in the country’s history – as head coach of England. No one except the small committee at the RFU – the now bewildered Don Rutherford and his colleagues Cliff Brittle, Bill Beaumont, Fran Cotton and Roger Uttley.

The challenge ahead was gargantuan. Woodward had just eight weeks to prepare for a brutal four-match autumn Test series against Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and then New Zealand again. ‘I was shitting myself,’ he said.

But he was also excited. Away from rugby, Woodward was a small businessman and he saw parallels between his old world and his new one. ‘I started that business from a bedroom and then I employed a couple of people and we took risks and we lost money and we made money, we mortgaged the house, and we did all sorts of stuff. I wasn’t a big corporate animal, I was a small businessman – which is what a rugby team is, you have thirty-odd people in a room, it’s not a huge operation. That’s how I used to think about it with the players: “It doesn’t really matter what’s happening out there,” I’d say. “It’s just here in this room that matters – it’s down to us.” That’s the message you’ve really got to get across: it’s now or never.

‘The England job came out of left field. I was probably more surprised than anyone when they chose me, but there must have been reasons that even I wasn’t aware of. I went in with an ambition to be the best team in the world and to get 80,000 people on their feet at Twickenham going nuts. And so you say, “Right, okay, have you got the raw materials with the players? Yes. Do we have the resources in terms of money? Yes.” So you look at it and you see that that ambition is possible. I was the first professional national coach so I had a blank sheet of paper, which was good because I was starting from scratch. But the flipside was that the first two or three years of any new venture are the toughest, and if you’re smart you come in after three years when some other idiot has taken all the initial crap.’

Woodward invited seventy of the country’s top players to Bisham Abbey for a meeting. Along with his team manager Roger Uttley and new assistant coach John Mitchell, he led the players upstairs to the Elizabethan Room – a long, narrow chamber that adjoined the chapel. The walls were decorated with sun-bleached wood panelling and chipped, peeling paint. The air was stale and dank. There weren’t enough seats. Players sat on tables and on the floor. It was a long way from the elite atmosphere that Woodward dreamed of.

Martin Johnson: Clive wanted to ultra-modernise what we were doing and wanted an exciting brand of rugby. He used a lot of business-speak and I was a bit sceptical about some of it but, overall, I was impressed. He had lots of good ideas. Some of them were very, very good. Some of them were okay and lived a little bit. And some were very strange and didn’t last long at all, but Clive was never afraid to try something different.

Matt Dawson: He wanted us to play fast, attacking rugby. That was music to my ears.

Lawrence Dallaglio: First and foremost, the biggest thing he brought was a change in mindset. He cops a lot of flak, Clive, from a lot of people because there’s a lot of envy, maybe, and jealousy of one person being rewarded for being successful. I don’t know what it is. But without him, England wouldn’t have achieved what we achieved. No doubt about that.

So the first thing was the mindset. He sat us all in a room in 1997 and said, ‘Look, I want you guys to be household names in a few years’ time. No one knows who any of you are, apart from your parents. I want you to be household names and for us to be the most successful side in the world.’ I think getting us all to commit to that as an ambition and verbalising it made a big difference. And he said, ‘Winning the Five Nations, of course it’s important, but if we want to be the best side in the world, we have to think about the other side of the world. Here’s a picture of the World Cup. I can’t see Wales’, Scotland’s or Ireland’s name on it. I can’t see France’s name on it. So let’s not be obsessed with beating these guys, we’ve got to be obsessed with beating this other three.’ And from that moment on, I think when we woke up in the morning we thought, ‘What are we doing compared to the best side in the world?’

Richard Hill: One of the first things he did was to bring in a TV make-over company to revamp the changing rooms at Twickenham. We were all asked what sort of things we’d like, from the paint colour to whether we wanted cubicles. We were locked out of the place in the build-up to the ’97 autumn Tests and then shown in before the first game and we were all bowled over with how much it had changed. We went in and it was all bright and spacious, with huge pictures on the walls and plaques with our names on them.

Matt Dawson: And he made the away changing rooms worse. He made them as dull and cold as possible. Then you’d walk into the tunnel and line up next to the opposition before running out and there would be all these tributes to great England victories that went right back to the first internationals dotted all along the walls. On the doors to the pitch in giant writing were the words: THIS IS FORTRESS TWICKENHAM.

Lawrence Dallaglio: He was a good guy, Clive, he was mischievous. He spoke to a guy at the RFU and said, ‘Where do New Zealand stay when they come over to England?’ And the guy looked it up and said, ‘They stay in this place called the Pennyhill Park Hotel.’ And Clive said, ‘Not anymore they don’t. Phone them up and tell them that the Pennyhill Park Hotel is no longer available.’ And he moved us in there instead. It was mischievous, but it was also a bit of a shot across the bows to New Zealand to say, ‘It’ll take us a bit of time, but we’re coming after you.’ I liked it. He was a leader not a follower. Everyone would look at New Zealand and try and copy what they were doing. But of course if you do that in anything, the people you’re copying are already moving on to the next stage and doing different things. He was a pioneer that took England in a different direction. He said, ‘You know what, if we do things this way, other people will start to copy what we do.’ And that’s exactly what happened.

Yes, he had a talented group of players, but he made all of those players – including me – look at things in a different way.

Clive Woodward: I took some of the senior guys aside for a private chat and I explained what I was planning. I wasn’t looking for approval, but I wanted to help them to understand the rationale. One or two of the players, who I’d define now as energy sappers, would be laughing about it and telling all their mates who weren’t playing any more how stupid it all was. There was a lot of ridicule. It wasn’t easy. Your job as a manager is to switch these guys over from being energy sappers to energisers and you have to do everything in your power to make that happen. But there comes a point that if you can’t switch them, they’ve got to go.

Woodward wanted to develop the England Way. He wanted his team to become the trendsetters, the ones with the revolutionary practices that others would want to emulate. And he needed a cavalry to help him do it. Dave Reddin was already a part-time fitness advisor. Woodward made him full-time. John Mitchell, the hard-nosed Kiwi coaching Sale, was recruited as forwards coach. Over the course of the next few months, Woodward added former rugby league coach Phil Larder as defence coach, began to utilise Dave Alred as kicking coach in a more regular fashion, brought in Phil Keith-Roach as scrummaging advisor and appointed Tony Biscombe as video analyst. Woodward had his inner sanctum. He would add to it later with the arrival of Brian Ashton, a visionary coach previously of Bath who had just endured an unhappy year as head coach with Ireland.

Jason Leonard: We hadn’t had backs, forwards, defence, attack, scrummage and kicking coaches before, let alone throwing-in coaches, tactical analysts and all the other people who eventually became associated with the team. I realise now that it was the right thing to do but, at the time, we were a bit alarmed at how quickly everything was changing and what all these new coaches were going to be doing. I think a lot of us were worrying that we’d end up having to train ten hours a day to allow them all to contribute.

Woodward also had a major call to make on his captain. Martin Johnson seemed the obvious choice after leading the Lions in South Africa in the summer, but he bypassed Johnson and went for Lawrence Dallaglio, the twenty-five-year-old back row who had captained Wasps to a league title before playing a seismic role with the Lions. Not for the first or last time, Woodward went against the grain.

Lawrence Dallaglio: It was such an honour to be made England captain, but then you look at your first four games. England had never played anything like it. To play all three southern hemisphere countries back-to-back-to-back-to-back. In hindsight, it was a bit of a tall order.