3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

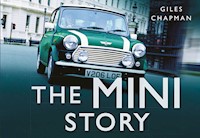

Very few cars inspire as much affection as the original Mini. It's the small car everyone loves to eulogise because it oozes energetic fun, classless minimalism and evergreen style. But it's also of massive historical importance: the 1959 Mini, designed by Alec Issigonis, set the template from which all successful compact cars have been created ever after. It was the technological wonder of its age. The original Mini was on sale for 41 years, during which its 5.3m sales made it the best-selling British car of all time – an achievement unlikely ever to be beaten. And just when it looked like the little car would shrivel and die, BMW had the vision to reinvent it as the planet's most desirable small car range, and put it back on the serious motoring map as the MINI. Here, award-winning writer Giles Chapman tells the whole, amazing story.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

THE MINI STORY

GILES CHAPMAN

First published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2014

All rights reserved

© Giles Chapman, 2011, 2012, 2014

Giles Chapman has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8528 7

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8527 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Introduction

Issigonis’s Great Little Idea

The Mini Cooper

Mokes, Marks and Italian Jobs

Special Editions

Enter the MINI

INTRODUCTION

The Mini revolutionised the layout of the compact car. It opened new frontiers in passenger accommodation, driver pleasure and owner economy, while its shortcomings never elicited more than passing gripes. The Mini brought engineering excellence and egalitarian style to everyone, and then changed the face of motorsport forever.

Today, we live in fickle times when a mainstream family car appears obsolete if it’s been in showrooms for five years. Yet the Mini was on sale for an extraordinary 41 years, during which time its pioneering design remained unchanged from the day in 1959 when it was revealed to a disbelieving world.

Did You Know?

In 1967, a bunch of students decided to see how many of them could squeeze inside a Mini. The uncomfortable answer was 24. The record was upped to 26 in 1986 in a Noel Edmonds TV stunt.

ISSIGONIS’S GREAT LITTLE IDEA

A motoring phenomenon, then; one made all the more remarkable by being the vision of a single individual – Alec Issigonis. The only son of an Anglo-Greek father and a German mother, Alexander Arnold Constantine Issigonis was born in 1906 in the Turkish town of Izmir (then called Smyrna). His engineer dad died when Alec was 16, and he and his mother settled in England. Two years later, he took to the road in a small Singer car, driving his mother all over Europe in it and learning, en route, how to keep it running. This experience helped steer him towards a three-year mechanical engineering course at London’s Battersea Polytechnic.

As he wasn’t too keen on maths, progress through academe was mediocre. Yet he showed intuitive design brilliance in preparing and racing an Austin Seven and, later on, building his own single-seater racing car stuffed with clever technical solutions and ingenious ways to minimise weight. These skills secured him a job at Coventry carmaker Humber, where he was assigned in 1934 to work on independent front suspension systems. Two years later, he was poached by Morris, based in Oxford, to perform similar duties.

In the turmoil of the Second World War, Issigonis’s can-do attitude served him well, and by 1941 he was chief engineer and leading a team planning (when time away from war work allowed) Morris’s all-new family car under the codename ‘Mosquito’. When it was launched as the Morris Minor in 1948 it was an instant hit, and showed the full scope of Alec Issigonis’s capabilities, from its neat packaging and mechanical simplicity to the sheer unalloyed pleasure of a car with well sorted steering and roadholding.

The Minor would become, in 1959, the first British car to top one million sales. Meanwhile, though, in 1952 Morris and arch-rival Austin merged to form the British Motor Corporation. The omens were not good for Issigonis. The influence in the merger was skewed towards Austin and he felt his power base was diminishing. Issigonis had grown accustomed to getting his own way – doing things by his preferred methods or not at all. A passionate and inspired lateral thinker, once he’d garnered his reputation for being ‘right’ about stuff, it often took just a thumbnail sketch and a persuasive argument to bedazzle people into backing his proposals. That wasn’t going to be so easy at BMC, so he opted to leave and join Alvis, where he was given free rein to create an all-new V8 luxury car.

The grass there turned out to be greener but no more gratifying. Three years of arduous work was rendered pointless when Alvis changed strategy and abruptly cancelled Issigonis’s project. A career crisis seemed inevitable, but a rapprochement with Austin saved the day. They needed him back at Longbridge where there was a distinct torpor in ‘The Kremlin’, the administration block where new models were created.

The Minor and Austin A30 economy cars had been consistently popular but other, larger Austin models struggled to tempt customers away from, in particular, Ford’s Consul and Zephyr. BMC chief Sir Leonard Lord made overtures to Issigonis, and he returned to the company in 1955 as deputy technical director . . . with the proviso that he had a free hand to oversee engineering programmes. The Minor, after all, had confounded its critics, so there was every reason to believe Issigonis could spin his magic again.

Did You Know?

Issigonis is said to have got the idea for using roller welders, to produce the Mini’s characteristic exterior seams, after watching a Morris Minor fuel tank being made.

The 1956 fuel crisis resulting from Egyptian president Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal then became the catalyst for the Mini. Public alarm over petrol rationing was countered by an armada of appalling, hastily designed three-wheelers and ‘bubble cars’. Lord thought his company should offer a better alternative – a real car, but in miniature – and he instructed Issigonis to funnel all his efforts into creating one. Aged 51 and familiar to colleagues as a pedant and a tinkerer, his enthusiasm for this task proved boundless. On paper napkins over lunch or in the little drawing pad he carried, he sketched and calculated constantly, consigning ideas to paper the moment they occurred to him. His team struggled to keep pace with his restless mental energy.

By early 1957, he’d drawn up his highly ingenious concept for ‘ADO 15’ (the project’s Austin Drawing Office codename) containing several leaps of engineering imagination. The new car would be smaller than anything BMC had built before, but still offer space for four adults and their luggage. 80 per cent of its ‘footprint’ would be devoted to passengers and cargo. Therefore, the car’s ‘package’ got his overriding attention. As it was to be just 10ft in total length, boot capacity would be limited, so Issigonis planned to utilise any spare spaces inside for accommodating cargo.

The car might have been shorter still. Late on in the design work, Issigonis had staff slice a design model in half and then inch the two ends apart until he finally cried ‘Stop!’ at 120in. All this meant minimising the intrusion the car’s drivetrain elements made on the passenger cabin, setting Issigonis on the miniaturisation trail. Front-wheel drive ensured the entire powerpack was unified in one place. The BMC A-Series engine – the only item Lord insisted be carried over – was mounted transversely across the front of the car, with the four-speed gearbox tucked underneath it, actually inside the engine’s oil sump. The radiator was placed at the side of the engine bay.

Did You Know?

As well as in Britain, the original Mini was manufactured at various times in Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Belgium, South Africa, Chile and Venezuela.

Along with the steering and front suspension, this lot was cradled in a subframe bolted to the Mini’s monocoque structure. Another subframe at the back held the rear wheels and suspension. Hard to believe today when you drive an original Mini but this did actually eliminate much of the vibration that would otherwise have arisen, as well as reducing stress on the structure, while the modular construction system meant it would be easy to develop Mini derivatives.

Power was transmitted to the front wheels via novel, Issigonis-created constant-velocity joints. They consisted of a ball bearing surrounded by three cages, two of which were connected, respectively, with the incoming and outgoing driveshafts. This, in turn, allowed a sufficient steering angle without distortion or undue articulation, minimising kickback in the steering . . . and endowing the little car with go-kart-like responses!

Did You Know?

More SU carburettors, made in Erdington, Birmingham, have been fitted to Minis than any other car – 5.5m in total.

The suspension itself was primarily space-saving, but also highly effective. It was perfected by consultant engineer Dr Alex Moulton using two compact cones with a layer of rubber in between instead of the usual coil, torsion or leaf springs. The upper cone was bolted firmly to the subframe, the lower rested on the wheel mount. As the rubber hardened under increasing pressure, this gave the classic Mini a progressive suspension set-up. It was so good at soaking up knocks that only small telescopic dampers – shock absorbers – were needed; they were fastened outside on upper front wishbones and rear longitudinal control arms for a smooth response to sudden pressures.

The car’s wheels were positioned at its extreme corners. Their unusually small diameter was to fit compact wheelarches that wouldn’t steal volume from the interior. Legend has it that Alec Issigonis said to Tom French, Dunlop’s chief designer, ‘Give me wheels this size.’ Mr French measured the space between Issigonis’s outstretched hands with a ruler. It was 10 inches. Whether true or not, Dunlop went on to make these specially sized wheels and tyres as part of Issigonis’s exacting requirements.

Did You Know?

Alec Issigonis designed the door bins in early Minis around full-size gin bottles – essential for his favourite tipple of a dry Martini.

There were sliding windows in the two doors. They were cheap to manufacture and the space in the doorframes they freed up was given over to deep storage bins for maps or handbags, moulded into the trim panels. A similar desire to open up storage space underscored Issigonis’s minimalist instrumentation in the form of one large, single, circular dial combining speedo, fuel gauge and warning lights for oil pressure, battery and headlamp full-on beams. Rather than being embedded in a dashboard, this sat in the centre of a full-width shelf, the space either side available for in-car clobber like hats, gloves, parcels and books. Below this were just about the only switches the driver needed, two toggles to activate the windscreen wipers and the lights.

Did You Know?

At one time, planners within the British Motor Corporation were going to call their new baby car the Austin Newmarket, to put it into line with the Cambridge and Westminster models.

The car was instantly redolent of Issigonis’s clever thinking. It also reflected his personal idiosyncrasies. As a chain-smoker, he made sure it had an ashtray. But he hated listening to the radio when he drove, so there was nowhere to install one. The separate starter button had almost died out on mainstream cars by the late 1950s, yet Issigonis insisted one be fitted. It jutted from the front footwell behind the gearlever, had its own shroud so it couldn’t be pressed accidentally . . . and would be quickly dropped.

It was an incredible feat to turn all this clever thinking into a working prototype in just seven months, but Issigonis made it happen. He invited the boss, Leonard Lord, to come for a spin around the factory grounds.

‘We drove round the Plant, and I was really going like hell,’ Issigonis recalled later. ‘I’m certain he was scared, but he was very impressed by the car’s roadholding – something that could never be said of other economy cars of the era. So when we stopped outside his office, he got out and simply said, “All right, build this car.”’