Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

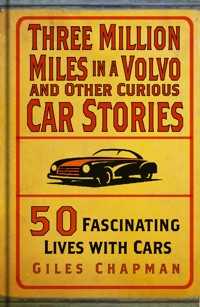

'An intriguing series of tales about love affairs with cars which, like human relationships, can go badly wrong.' – Christian Wolmar, best-selling author of The Subterranean Railway and Fire & Steam Three Million Miles in a Volvo and Other Curious Car Stories is a whistle-stop tour of fifty fascinating petrolheads and how they changed car culture for good. Meet: The Prince of Darkness! The Sweeney's ace stunt driver! Renault's doyenne of colours and fabrics! Discover: A pathetic steam car! Metal underpants! The unseen brilliance of Jaguars! And find out exactly how one man adored his Volvo so much that he drove it around the world 120 times to cruise into the record books.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover Illustration:Alexkava/Shutterstock.com

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Giles Chapman, 2024

The right of Giles Chapman to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 550 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

INTRODUCTION

GERRY ANDERSON

TV sci-fi legend and futuristic car fanatic

JACK BARCLAY

Rolls-Royce dealer with a reckless past

FLAMINIO BERTONI

Citroën’s shaper of curves and corrugations

SIEGFRIED BETTMANN

Founder of Triumph motorcycles, and then cars

SIR JOHN BLACK

Tyrannical force behind Standard and Triumph

JOHN BLATCHLEY

His passion was the ‘flying drawing room’

NILS BOHLIN

Three-point plan to save millions of lives

PETER BRAYHAM

Tough guy stunt driver for The Sweeney

MARIO TOZZI-CONDIVI

Ducking and diving Italian car salesman

MARY DAVIS

Upped the stakes in the LA racing community

TERENCE DELANEY

Race pioneer turned north London metal-basher

ALEXANDER DUCKHAM

Black gold trail from Millwall to Trinidad

HARRY FERGUSON

Tractor tycoon who would not be crossed

BORIS FORTER

Secret life of the perfumier petrolhead

PIETRO FRUA

Italian car stylist who hated screaming chrome

MAURICE GATSONIDES

Split-second inventor of the speed camera

VICTOR GAUNTLETT

Buccaneer determined to keep Aston Martin old school

DAVID GITTENS

A truly awesome experience with the Ikenga

ALBRECHT GOERTZ

Aristocratic sports car loner of New York

ALAN GOOD

Impatient entrepreneur who saved Lagonda

IRV GORDON

He drove 3.2 million miles in his Volvo

EUGENE GREGORIE

Boat-mad designer of the first British Ford

WALTER HAYES

PR guru who sprinkled performance stardust

LESLIE HORE-BELISHA

Flash of inspiration from an awkward minister

CHRIS HUMBERSTONE

Maverick car designer with too much on his plate …

ROBERT JANKEL

From the rag trade to replicars

DEAN JEFFRIES

Hollywood’s other film and TV car creator

CECIL KIMBER

MG boss whose career came off the rails

BOB KNIGHT

Fussy engineer gave Jaguars their magic

ANTHONY LAGO

Fierce guardian of Talbot’s fading glamour

VINCENZO LANCIA

A near-miss with Mamma made his cars surefooted

LES LESTON

Go-faster ‘Daddio’ of car accessories

WALTER LINES

Tri-ang toys grandee behind Minic and Scalextric

LEONARD LORD

What does BMC stand for? Len would tell you

JOSEPH LUCAS

Do not toast ‘The Prince of Darkness’

PAULE MARROT

Fabrics expert gave Renault a beautiful palette

SHEKHAR MEHTA

Avoiding giraffes at 110mph, made easy

PETER MONTEVERDI

Swiss carmaker who was snubbed by Enzo Ferrari

GERALD PALMER

Designer of (the whole of) the Jowett Javelin

PETER PELLANDINE

His speed record attempt ran out of steam

LOUIS RENAULT

The most hated man in French motoring history

OSMOND RIVERS

From Empress line to ‘Docker’ Daimlers

SIXTEN SASON

Added spice for Swedish industrial design

PETER SELLERS

Film star with ‘metal underpants’

CHARLES SYKES

Artist behind the Spirit of Ecstasy

JACK WARNER

The car years of Dixon of Dock Green

JAMES WATT

Energetic backer of the Healey car

RAYMOND WAY

Used car super-salesman from central casting …

WALTER WILSON

Advanced the technique of changing gear

ELSIE ‘BILL’ WISDOM

Go-girl of early British motor racing

Introduction

Over my years as a writer on cars I’ve been lucky enough to actually meet some of the amazing characters on the pages ahead. For others I’ve compiled their obituaries for national newspapers, or retrospective tributes for magazines.

In a couple of cases, major profiles researched and written by me stand today as definitive accounts of fascinating lives (and usually previously unknown ones), about which you won’t find much more by dredging the internet. I’ve also been able to draw on a great many interviews I conducted when the people I write about here, or their descendents, were still alive. Through those direct quotes, their experiences and opinions help relay their tales.

It’s wonderful to be able to bring them all together under one, decidedly strange title. Irv Gordon, with his thirteen-times-to-the-moon-and-back Volvo P1800S, is not typical of the people included here. But then no one is. They all have contrasting relationships to automotive history; that could be in designing, making, selling, handling or influencing cars. Apart from the fact none are around any longer (save for David Gittens), that’s the sole unifying factor.

Irv himself was an oddball. Precisely why he got so attached to his driving seat is hard to really fathom. Nor is it easy to know the reasons why Raymond Way cultivated his second-hand car salesman’s patter. Leonard Lord and Bob Knight, respectively aggressive and obsessive to ridiculous lengths, remain enigmas. Who can truly know another person?

You won’t find one racing driver after another here, lost in a barrel of race results and lap times. Nor are the familiar careers of Henry Ford, Enzo Ferrari or even John DeLorean getting another airing. These fifty fantastic petrolheads will probably be new to you, but their intriguing existences, collectively, should shed light on the motivation and achievements of curious lives around cars.

Giles Chapman, 2024

GERRY ANDERSON

TV sci-fi legend andfuturistic car fanatic

Rolls-Royce never admitted it, but Gerry Anderson probably did more to promote its cars than its own public relations staff.

‘Yeah, I’d love to know how many children grew up and bought a Rolls after falling in love with Lady Penelope’s FAB 1,’ he said, referring to the iconic six-wheeled limousine of Anderson’s 1965 puppet show Thunderbirds. It had a sliding glass roof, a central driving position for shifty Cockney chauffeur Parker, and a concealed rocket launcher behind its grille. The FAB 1 registration number matched the hip ‘F.A.B.’ radio sign-off of International Rescue, run by Jeff Tracy and his fearless sons Scott, Virgil, Alan, Gordon and John, as well as their titled British associate.

One tiny, 6in-long version was fashioned for inclusion in the fantastic landscape sets and another – the definitive one – was a 7ft-long plywood model for filming in scenes featuring the actual puppets. Rolls-Royce officially sanctioned the use of its trademarks with one stipulation. Never must the words ‘Roller’ or ‘Rolls’ emanate from the puppet characters – only ‘Rolls-Royce’.

Gerry Anderson, centre in dark shirt, filming UFO. (Courtesy Jeroen Booij, www.jeroenbooij.com)

Thunderbirds was a worldwide hit, and Anderson’s boss Lew Grade gave him a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow as a surprise thank-you present; ‘A Rolls-Royce was my dream, just like everyone else,’ said Anderson. He kept it for eleven years before a costly divorce saw it replaced by a Mini. By 1983 he could afford to buy a brand-new Silver Spirit. It was a disaster. ‘I’m well over 6ft tall and it was just impossible to see the instruments properly,’ he recalled. ‘The hydraulics needed attention between 6,000-mile services. I had so much trouble with it, I became totally disenchanted. When I complained it leaked I was informed by a man from the factory this was merely “water pervasion”.’

Gerry Anderson began work in the film industry in 1942, setting up in business as a wannabe Samuel Goldwyn in 1957. Trouble was, the only commission he could land was making children’s puppet shows for ITV. He was never proud of Twizzle, Torchy the Battery Boy and Supercar, but they paved the way for Fireball XL5, Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons, Thunderbirds of course, and Joe 90 – all co-created with his wife Sylvia. You could indeed sometimes see the strings but Anderson’s zeal for technical innovation saw his ‘Supermarionation’ processes – chiefly electronically synchronised puppet movements – and a gifted special effects team turn the shows into TV classics.

All Anderson could afford as his first car was a £40 Morris 12: ‘It was described as a “good runner” but one day I stepped on the running board and it promptly collapsed.’ After Grade bought his production company, Anderson could afford a new Jaguar Mk X: ‘It was good looking and exciting, like all Jaguars, but it was a problem car, potent though it was.’

The Andersons moved into full-size live action with UFO in 1970, a sci-fi saga where the SHADO organisation defended Earth from alien flying saucers, cloaked in secrecy to prevent mass panic, and starring Canadian Ed Bishop as Commander Straker. Anderson’s only previous dalliance with building full-size vehicles was a road-going version of FAB 1, commissioned in 1966 to promote the film Thunderbird 6, and two futuristic coupés built by Alan Mann Racing in 1968 for another unsuccessful movie entitled Doppelgänger. These were recycled as UFO’s ‘Shadocars’, although they were little more than props – flimsy, underpowered and perilous to drive. ‘I wanted the cars to look the way they might be ten years hence,’ Anderson told his biographer Simon Archer, and indeed the DeLorean DMC-12 subsequently adopted a similar wedge-shaped, gullwing design theme.

In 1972, Anderson produced a detective series called The Protectors. It starred Robert Vaughn and Nyree Dawn Porter, and Anderson’s own Silver Shadow featured in the opening credits. He recalled:

On the first day of filming, I turned up at Elstree to find the car park crammed full of brand new cars. The manufacturers just delivered them all because they’d heard we were making the show. We made fifty-two episodes and we ‘cast’ the cars for each script … rather like we did the actors.

In 1983, during the filming of another puppet show, Terrahawks, Anderson turned to Rolls-Royce again:

We designed a new Rolls-Royce for the show, which we called Hudson. We needed one small model to use on the special effects sets and one larger one, a third real size, for close-ups with the puppet characters. It was designed to change colour by covering it in tiny glass beads to reflect spotlights.

FAB 1, full-size car built for promotion.

For years, a Thunderbirds remake had been mooted. When it appeared as a 2004 movie featuring real actors, its creator’s name was notably absent. Emblematic of the film’s travesty was the new FAB 1; the pink six-wheeler had become a Ford. Anderson told the BBC: ‘It was disgraceful such a huge amount of money was spent with people who had no idea what Thunderbirds was about and what made it tick.’ He was close to making a TV reboot of his most famous show when he passed away in 2012 aged 83. Then a CGI remake called Thunderbirds Are Go was aired in 2015 and brought the Tracy family saga to a whole new generation of children.

JACK BARCLAY

Rolls-Royce dealerwith a reckless past

The Jack Barclay showroom on the corner of Berkeley Square and Bruton Street in London remains one of the most opulent you’ll find in any capital. But how many of the world’s super-rich who’ve passed through its doors since its opening in 1953 know anything about Jack himself?

John Donald ‘Jack’ Barclay was born on 7 February 1900 in Marylebone, and as a sporty schoolboy he was packed off to boarding school in Ramsgate, Kent, by his estate agent father. Jack lied about his age to join the Royal Flying Corps at the end of the First World War, where he served as a motorcycle dispatch rider. Upon demobilisation he headed straight into the motor trade as a motorbike salesman, simultaneously competing in ’bike trials as a way to find customers. In 1920 Jack was knocked unconscious on the MCC Trial when the sidecar he was in overturned and hit a wall. It occurred to him that, maybe, the future was on four wheels.

So in 1922 he set up in business with Robert Wyse in the heart of London’s booming car trade in Great Portland Street. Barclay & Wyse took on agencies for Sunbeam, Singer, Citroën, Morris, Bentley, Hispano Suiza and Rolls-Royce. Jack’s favourite brand, though, was Vauxhall, which at the time made Britain’s most illustrious sports cars. He well understood the publicity value of racing, and in 1924 he started campaigning a two-year-old, ex-Tourist Trophy Vauxhall 30/98. This diminutive driver in his distinctive black overalls soon caused eyebrows to raise.

Jack Barclay, right, with W.O. Bentley.

In the autumn meeting at the Brooklands track in Surrey, Jack kissed 106.42mph in that Vauxhall to beat Woolf Barnato in the Long Handicap at an average speed of 96.2mph, although he was reprimanded by the race stewards for dangerous driving. The year after he set eight speed records in the International 3-litre Class. But his speed freakery was reckless, his near-misses the stuff of much paddock gossip. In the 1926 Easter 100-mile Brooklands race, for example, while overtaking slower cars he drove perilously near the edge of the unfenced, 60ft precipice of the banking. Avoiding one that pulled in front of him, his rear wheels skidded almost over the edge and his car slid sideways at 110mph, nose down, along the rim of the banking. It then spun around completely, slithered down the banking narrowly missing competing cars, and continued backwards at over 80mph before swinging back again to face its original direction. Barclay kept his engine running throughout and rejoined the race. This kind of thing endeared him to the ‘Bentley Boys’ coterie of playboy racers, which included Barnato and Sir Tim Birkin, although he simply wasn’t posh and rich enough to fully join their circle.

Probably while trying to keep up with these high rollers, Jack ran up a huge gambling debt at the casino in Le Touquet, and his forceful mother Augusta Barclay agreed to settle it – if he made the 1926 racing season his last. To this he reluctantly agreed and, with a new-found business focus, in 1927 he ditched his partnership and founded Jack Barclay Ltd, opening new premises in George Street, Hanover Square, outside which his own Rolls-Royce Phantom I sedanca de ville made a fitting attraction. There was, though, one return to Brooklands when Jack drove a Bentley 4.5-litre in the October 1929 BRDC 500-mile race, partnered by pukka Bentley Boy Frank Clement. The race again almost ended in disaster. Jack was doing 130mph when a front tyre burst and the car skidded to the top of the banking, made two complete spins, and shot to the very brink. Despite driving with stitches still in place after an operation, Jack wrestled the Bentley to stop it overturning and limped to the pits. Clement then took over and won at a 107mph average speed. The Motor commented dryly: ‘At Brooklands one would naturally expect Barclay’s banking to be good.’

A 1929 society magazine reported Jack as the ‘finest luxury motor car salesman in the trade’, adding: ‘He has a rather rusty voice, but is silver-tongued.’ The rasping was down to heavy smoking. The move to Berkeley Square, and the clearly delicious synergy with his surname, was first planned in 1939 but only happened fourteen years later. It was backed to the hilt by Rolls-Royce; the company had been enamoured of Jack’s reputable salesmanship since 1934, in which, despite the ongoing economic depression, he sold more Rolls-Royces and Bentleys than any other dealer … and 40 per cent more than the year before.

He ran his empire there until 1967, which included ownership of coachbuilder James Young and from 1962 the Fiat distributorship for the whole of London. From 1946 home was the 1,000-acre Little Baldon Farm in Oxfordshire, where Jack bred prize Aberdeen Angus cattle, yet he had only enjoyed one year of bucolic retirement there as he died from a long-term illness on 9 July 1968.

Showroom at George Street, Hanover Square.

FLAMINIO BERTONI

Citroën’s shaper ofcurves and corrugations

André Citroën, never easy-going, had an especially short fuse in spring 1932. He was planning to disrupt the family car market with his all-new range, later feted as the ‘Traction Avant’, and work on its radical front-wheel drive drivetrain and frameless monocoque structure was progressing well. But the fierce company head had just torn up the third design proposal from his bodywork team.

One senior Citroën engineer had, however, made the canny signing of a 30-year-old artist – an Italian with a mop of thick, black hair he’d encountered toiling in the backroom at one of Citroën’s metal-stamping contractors. On 27 June 1932 a place was found for him in the febrile design office at the company’s HQ, and Flaminio Bertoni was told to get creative.

Unlike his colleagues, Bertoni was not given to diligently making plan drawings. As a sculptor, his thinking was three-dimensional, and he decided to refine his proposals in large-scale models shaped using clay – then a radical idea for the car industry. Bertoni went for an elegant, harmonious style that people who cared nothing about engines would be drawn to. The low roof, lack of running boards and ground-hugging stance suggested sprinting greyhound rather than plodding St Bernard.

Flaminio Bertoni sculpting Traction Avant clay model.

When André Citroën saw the work in spring 1933, his pince-nez almost flew off to unfurrow his normally irritated brow. This was exactly what he wanted, and Bertoni’s talent was extolled.

Actually, it had been spotted long before. Bertoni was born in Varese in northern Italy on 10 January 1903. His father, a tailor, died when Flaminio was 15, and the young man then began an apprenticeship at the nearby Macchi bus bodyshop, honing excellent skills in joinery and metalworking.

It was evident then he was a natural artist, and confident enough to enrol himself at Varese’s School of Fine Arts in his own time to develop his drawing and sculpting. He jumped at the chance of a study trip to Paris, discovering Italian artists at the Louvre such as Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. Indeed, in 1923 he began working in the French capital for various coachbuilders including Felber and Rothschild.

Bertoni was eventually forced to return to Varese, where his mother was gravely ill, and the Macchi company was glad to have him back. He also opened a studio, and in 1929 gained his independence as a consultant, splitting time between paid design work and making his own pieces. The Bohemian life in Paris exerted an enormous pull, though, and he returned in 1931.

Once he’d joined Citroën, the company endured bankruptcy, the death of its founder, and a takeover by Michelin, although Bertoni was fully occupied with the myriad versions of the Traction Avant. He tended to work alone and very fast, sometimes finalising designs in mere hours. Then it was off to his studio to indulge his real passions, the results of which brought him numerous medals at art exhibitions.

He was the Citroën styling department and those teenage skills as a maker underpinned his output, demonstrating extraordinary versatility. The crucial 2CV of 1948, for example, was finessed from rudimentary prototypes to production-ready form by Bertoni, making its stark utility bearable. That task completed, in 1949 he gained an architectural degree and began work on various projects in suburban Paris.

The Citroën DS is the pinnacle of his car work. For many it remains the most thrilling automotive design ever, and it won the honorary prize at the 1957 Milan Triennale exhibition. ‘The difference between the 2CV and DS, one highly functional, the other highly stylised, shows Bertoni’s ability to conceptualise the nature of an automobile in a highly abstract way,’ wrote one design critic. Bertoni put it more baldly: ‘Everything that’s volume is sculpture. The car body has volume. So the two things are the same.’

Bertoni was the antithesis of the corporate man (despite his work to reduce Citroën’s double-chevron logo to minimalist purity). He spent much of his time in his own studio workshop in Antony on Paris’ southern fringes, and in 1956 he was in St Louis in the US to see his patented house-building system create 1,000 family homes in 100 days.

Citroën H-type van and DS19, contrasting Bertoni designs.

In 1961 Bertoni’s Citroën Ami was unveiled and its startling profile and the world’s first styled headlights immediately split opinions. Bertoni had become a nationally significant figure, recognised by his elevation to Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres that year. Sadly, and while freeform-sketching the sporty DS that ultimately became the SM, he died in 1964 from hepatitis after a stroke, aged 61. His work is celebrated in an intimate museum in Varese, opened by his son Leonardo.

Enough Tractions, 2CVs, DSs and Amis survive to allow anyone reasonably to own a Bertoni original. Today, however, it’s the corrugated panels of his Citroën H-type van that have, surprisingly, planted his work in countless public spaces – it’s the vehicle of choice for the best street-food vendors, coffee stalls and festival bars everywhere …

SIEGFRIED BETTMANN

Founder of Triumph motorcycles,and then cars

It’s not quite true that the creator of Triumph cars, motorcycles and bicycles started his enterprise penniless. Once Siegfried Bettmann had a sound business plan, his family invested £500 in 1889 to kickstart his modest Coventry factory.

The risk was minimal because the first pushbikes were bought in from William Andrews & Co. in Birmingham, and jazzed up with ‘Triumph’ decals. Bettmann and his junior partner Mauritz Schulte didn’t actually know how to make anything, but the cycling craze was in full swing, and these two hard-bitten former travelling salesmen were eager to cash in.

Bettmann was born in 1863 into a Jewish family in Germany’s metalworking heartland of Nuremberg, although his father was actually a country estate manager. Young Siegfried boldly set off for London aged 20 to seek his fortune and, on his first night in digs in Islington, he met Schulte, from Hanover, who was chasing similar dreams.

Initially Bettmann found lowly grunt work, using his translation skills to compile business directories. These publications fed the numerous crazes and bubbles that characterised the Victorian era, and Bettmann jumped ship to an apparent winner: selling sewing machines. His inexperience made it a bad call because the boom in these was ending, but he adroitly spotted the next big thing: bicycles. He started an export business under his own name, and it proved so successful he had friends clamouring to invest in S. Bettmann & Co.; even the landlord of his first premises, in London’s Golden Lane, put money in. In November 1886, Mauritz Schulte bought in too, sinking his £250 life savings into the renamed Triumph Cycle Company. Schulte was then dispatched for two months to William Andrews’ factory to learn how bicycles were constructed, and in 1889 the company started building its own from scratch.

Bettmann cannily identified the ‘motor-cycle’ as his next money-spinner, and by 1905 the partners had built a prototype. It was a mark of Bettmann’s prosperity that in that same year he moved into a substantial mansion at 9 Elm Bank in North Park, Stoke. This made an appropriate residence for the man who, in 1913, became the mayor of Coventry.

Siegfried Bettmann.

If it was a shock for a German native to sport the municipal chain then it was no surprise that he was stripped of the title in 1914 as the First World War erupted. Yet 30,000 Triumph motorcycles were ordered for the war effort; by 1918, the company was probably the planet’s biggest motorbike manufacturer.

Bettmann was a Labour Party supporter, and a friend of its leader Ramsay MacDonald (who was entertained at Elm Bank twice). He also had a stint as chairman of Coventry’s Standard Motor Company, was a bigwig in the city’s Chamber of Commerce, a Freemason and a JP. His ire, meanwhile, was directed towards Schulte, whom he grew to loathe and eventually wouldn’t even speak to (a proper sending to Coventry, that). In 1919 Bettmann cajoled his board into ousting Schulte with a £15,000 golden handshake. Taking his place as works manager was Vivian Holbrook – the former War Office staff captain who’d placed the army’s first ever order for 100 Triumph motorbikes.

What Schulte and Holbrook shared, and what Bettmann came round to, was a longing to enter the car market. After a shaky start Triumph hired Stanley Edge, designer of the successful Austin Seven, to work on a superior rival product, which they named the Triumph Super Seven in 1927. With upgrades like four-wheel hydraulic brakes and a luxurious interior, more than 10,000 examples had sold by 1930.

That year Bettmann, aged 67, stepped back to become vice to his empire’s new chairman, local landowner Lord Leigh, with Holbrook promoted to managing director. For car enthusiasts, Triumph suddenly started to get exciting because Holbrook recruited Donald Healey to turn the cars into stylish, high-performance machines.

Holbrook’s decision to stop making motorcycles horrified Bettmann. So a compromise was reached. This part of the company was sold to Ariel in 1937, and Bettmann became chairman of the new Triumph Engineering for a couple of years. Triumph’s Coventry car factory was bombed into oblivion in the Second World War, but the former alderman Bettmann’s allegiance to Britain this time was undeniable. Afterwards he enjoyed a comfortable retirement at Elm Bank. He married Annie ‘Millie’ Meyrick in 1895, after whom the couple named their Annie Bettmann Foundation, established in 1914 to help young Coventry entrepreneurs get their businesses rolling. Some 104 years later it was amalgamated into the Heart of England Community Foundation, and some of its funds went to local creative arts businesses to make Coventry the UK’s City of Culture in 2021.

1937 Triumph Gloria roadster.

In a strange reversal of fortunes, in 1983 the Triumph name on cars went out with a whimper as the badge on a UK-built Honda, but Triumph Motorcycles was on the cusp of a revival that has, once again, made it one of the greatest marques in contemporary biking.

SIR JOHN BLACK

Tyrannical force behindStandard and Triumph

The two fellows responsible for Triumph being a notable classic British sporting car marque were probably feeling pretty chipper on that fateful November morning in 1953. They understood each other pretty well.

Six months earlier, their jointly conceived TR2 – now in definitive form – had been a massive talking point at the Geneva motor show. Then in May the minimum of trickery was employed to get it to pull 125mph on the Jabbeke motorway in Belgium. The TR2 was real excitement, and there’d been precious little of that at Standard-Triumph recently.

Ken Richardson was an engineer laid off by BRM and taken on at S-T; he’d cast a critical eye over the TR2 proto-type and declared it amateurish and ill handling. Sir John Black, the company’s managing director, was the car’s champion – he badly needed an MG rival to pull in US export dollars – and would not normally brook any such criticism. For once, though, Black chose to listen. It was a change of heart perhaps prompted by a string of car launches, all Black’s pet projects, which had failed to live up to his own deluded expectations. He let Richardson take the project on and do whatever necessary to give it credibility. Now, in November ’53, the first ones were being built and there was a ray of sunshine on the company’s perpetually cloudy horizon.