1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Librorium Editions

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

“The Miracle of St. Anthony”—whatever the exact date of its writing, and that is a point which the author himself has probably forgotten,—belongs in flavour and spirit, to that early period of the career of the Belgian seer and mystic to which Mr. James Huneker referred when he wrote “There is no denying the fact that at one time Maeterlinck meant for most people a crazy crow, masquerading in tail feathers plucked from the Swan of Avon.” For it was to Shakespeare that he was first compared, though the title “the Belgian Shakespeare” was applied ironically by some, just as later manifestationsof his genius won for him the appellation of “the Belgian Emerson.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

THE MIRACLE OF SAINT ANTHONY

The Miracle of Saint Anthony

By Maurice Maeterlinck

Translated by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos

, 1918

© 2023 Librorium Editions

ISBN : 9782385740177

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

This play was written some ten or twelve years ago, but has never been published or performed in the original. A translation in two acts was printed in Germany a few years before the war; but the present is the only authorized version, in its final, one-act form, that has hitherto appeared in any language.

Alexander Teixeira de Mattos.

Chelsea, 27 February, 1918.

CHARACTERS

Saint Anthony

Gustave

Achille

The Doctor

The Rector

Joseph

The Commissary of Police

A Police-sergeant

A Policeman

Mademoiselle Hortense

Virginie

Léontine, an old lady

Valentine, a young girl

Other Relations and Guests

The action takes place in the present century, in a small Flemish provincial town.

INTRODUCTION

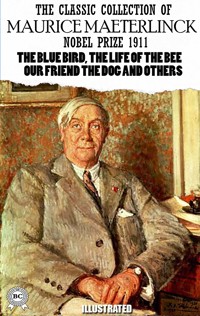

“The Miracle of St. Anthony”—whatever the exact date of its writing, and that is a point which the author himself has probably forgotten,—belongs in flavour and spirit, to that early period of the career of the Belgian seer and mystic to which Mr. James Huneker referred when he wrote “There is no denying the fact that at one time Maeterlinck meant for most people a crazy crow, masquerading in tail feathers plucked from the Swan of Avon.” For it was to Shakespeare that he was first compared, though the title “the Belgian Shakespeare” was applied ironically by some, just as later manifestations of his genius won for him the appellation of “the Belgian Emerson.” But “The Miracle of St. Anthony” differs from the other plays of what may be called “the early Maeterlinck.” Most of them, to quote Mr. Edward Thomas, have a melancholy, a romance of unreality, a morbidity, combined with innocence, which piques our indulgence. He has no irony to put us on the defensive. But irony is the very essence of “The Miracle of St. Anthony.” Nor does the scene of the little play belong to that land of illusion, that mystic border country, half twilight and half mirage, in which so many of the early plays were laid. The St. Anthony from whom the satire takes its title may be the blessed St. Anthony of Padua, but the atmosphere is unmistakably the gray, sombre Flemish atmosphere that Maeterlinck knew in his early youth, while the Marionettes who speak the lines were drawn, not from Fairy-land, but from some town of the Low-Countries.

Maeterlinck’s nationality was not a mere chance of birth, but a heritage of many generations. The Flemish family of which he was born in Ghent on August 29, 1862, had for six centuries been settled in the neighborhood. His childhood was passed at Oostacker, in a house on the bank of a canal connecting Ghent with Terneuzen. So near was the water that the ships seemed to be sliding through the garden itself. The seven years spent at the Jesuit college of St. Barbe were not happy years, but there were developed his first literary aspirations, and there he formed certain friendships that lasted into later life. At the University, where he studied for the Bar, he met Émile Verhaeren, who was destined to stand out with King Albert, Cardinal Mercier, and Maeterlinck, as one of the great figures of the land when Belgium came to experience her agony.

But it was not in Maeterlinck to settle down to a lawyer’s work and a bourgeois life. “Like Rodenbach,” said M. Edouard Schuré, “he had dreamed alongside the sleeping waters of Belgium and in the dead cities, and, though his dream did not become a paralysing reverie, thanks to his vigorous and healthy body, he was already troubled in such a way that he was unlikely to accept the conditions of a legal career.” So, when at twenty four, he made his first trip to Paris, though the visit was professedly in the interests of his studies, it was with the result that he plunged definitely and whole heartedly into literature. To Villiers de l’Isle Adam, and others of the ultra modern school, he was introduced by an old copain of the Jesuit college, Gregoire Le Roy. Le Roy read to the group Maeterlinck’s “The Massacre of the Innocents,” a perfectly Flemish piece of objective realism. It was applauded, and soon after appeared in “La Pléïde,” a short-lived review which also printed some of the poems collected in “Serres Chaudes.”

That first stay in Paris was one of about six months. Returning to Ghent, he conformed to the wishes of his family to the extent of dabbling a little at the Bar. But his heart was with “La Jeune Belgique,” to which he had been introduced by Rodenbach, author of “Bruges la Morte,” and for which he was writing his poems. Then in 1889, when he was twenty-seven years of age, “Serres Chaudes” was published, and with it went the last tie binding him to the law.

Continuing to live in his native Oostacker, his days were divided between writing, tending his bees, and outdoor pastimes. As a member of the Civic Guard of Ghent he was as poor an amateur soldier as Balzac had been when enrolled in the National Guard of the France of his time. His musket was allowed to rust until the night before an inspection. Material surroundings meant little to him. As with Barrie, the four walls were enough. He could people the homely room to suit his fancy. In imagination a table became a mountain range, a chair the nave of a superb cathedral, a side-board a limitless expanse of surging ocean. Through the window he could look out over a country suggesting the scene of his early play, “Les Sept Princesses,” “A dark land of marshes, of pools, and of oak and pine forests. Between enormous willows a straight and gloomy canal, on which a great ship of war advances.”