Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

London's old buildings hold a wealth of clues to the city's rich and vibrant past. The histories of some, such as the Tower of London and Westminster Abbey, are well documented. However, these magnificent, world-renowned attractions are not the only places with fascinating tales to tell. Down a narrow, medieval lane on the outskirts of Smithfield stands 41–42 Cloth Fair – the oldest house in the City of London. Fiona Rule uncovers the fascinating survival story of this extraordinary property and the people who owned it and lived in it, set against the backdrop of an ever-changing city that has prevailed over war, disease, fire and economic crises.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my sister, Lindsay Rule.

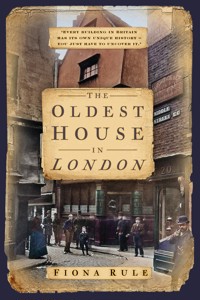

Front cover illustration: The church of St. Bartholomew the Greatand surrounding area; the Dick Whittington pub on the corner of a street.Photograph. (Wellcome Collection)

First published 2017

This paperback edition published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Fiona Rule, 2017, 2023

The right of Fiona Rule to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75098 647 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1 Land Grab

2 The Eagle & Child:The Oldest House in London is Built

3 The Proud, Bloody City of London:Cloth Fair in the Civil War

4 The Sign of the Red Cross:Death Visits Cloth Fair

5 London Was, but is No More:Or How the Oldest House in London Very Nearly Wasn’t

6 Knavery in Perfection:The Riotous Heyday of Bartholomew Fair

7 By Ordinance of God:The Wesley Brothers at Cloth Fair

8 The Newgate Six:Cloth Fair and the Gordon Riots

9 Property is Power:Cloth Fair at the Heart of Radical Politics

10 A Piece of Tyrannical Impertinence:Cloth Fair and the First Modern Census

11 The Death of Old London:Part One

12 The Death of Old London:Part Two

13 Saving London:Seely, Paget and the Second World War

14 Preserving the Past for the Future

Epilogue

A Walk Around Cloth Fair

Afterword

Select Bibliography

Foreword

Searching for London’s Oldest House

Finding the oldest house in London was not an easy task. Over the centuries the city’s buildings have adapted and evolved to meet the demands of an ever-changing metropolis. Consequently, some structures that were originally built as houses are now commercial premises while ancient workshops and warehouses have been converted into sought-after private homes. The inexorable growth of the metropolis over the centuries has also meant that houses that once stood in an Essex, Surrey or Middlesex village now possess a London postcode.

Early on in my research, I developed simple but strict criteria for identifying the oldest house in London: it had to have been built as a private residence within the precincts of the city and it still had to be someone’s home today. My self-imposed rules eliminated several strong candidates. For example, the elaborate building now known as Prince Henry’s Room at 17 Fleet Street and the Staple Inn on High Holborn were built in 1610 and 1585 respectively, but both were originally inns, not private houses. The Old Curiosity Shop on Portsmouth Street WC2 predates both of the above and the upper rooms of this extraordinary sixteenth-century property were undoubtedly domestic for much of its long history. However, today, as its name suggests, the building is a shop, selling an interesting range of rather expensive shoes. Likewise, 74 and 75 Long Lane EC1 were built as houses back in the late 1590s but ceased to be private homes many moons ago. Further out of central London, stranded on the grimy northern approach to the Blackwall Tunnel, Bromley Hall’s elegant Georgian façade conceals a much earlier house that was built in the 1490s by Holy Trinity Priory. However, its location was not part of London until the late 1800s.

Ultimately there was only building that met my criteria. Built as a domestic residence in 1614, it originally formed part of the City Ward of Farringdon Without. Today it is still used as a private home and its story, along with that of its inhabitants, is told in this book.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the staff of London’s archive centres and Matthew Bell, the current owner of London’s oldest house, whose help has been invaluable. I would also like to thank my husband Robert, the rest of my family, and my friends, particularly Sharon Tyler, for their interest and support. As always, the wisdom and guidance of my agent, Sheila Ableman, has been invaluable and I am very grateful to The History Press for their belief in me and my books. Finally, I would like to thank Jean Rule for her enthusiasm and encouragement over the years. Sleep well.

Introduction

This is the story of a house. Today it is the oldest private home in the City of London, but its outward appearance gives few clues to its fascinating and ancient heritage. In fact, most people are unaware of its existence. It hides in plain sight at 41–42 Cloth Fair – a narrow street sandwiched between the glass and iron splendour of Smithfield Market and the high walls of Bart’s Hospital. Cloth Fair’s Smithfield entrance yields an unpromising view, but anyone who cares to venture a little further down the street will be rewarded. Victorian brick quickly gives way to ancient stonework as the magnificent Church of St Bartholomew the Great looms into view. Slip through the gate in the railings and you find yourself in a shady churchyard where the bustle and noise of the nearby market dulls to a distant murmur. Here, a straggly collection of trees and shrubs frame a strangely timeless view of 41–42 Cloth Fair – its fine gabled projections and glinting leadlight windows tantalisingly hinting at a history that stretches back into a time long forgotten.

Over the centuries, 41–42 Cloth Fair has weathered many storms as, all around it, history unfolded. Its inhabitants witnessed events that moulded Britain into the country that it is today. They saw plague, fire and war. They struggled through financial crises, religious strife and commercial revolutions. They are our ancestors, and through their own personal stories we can learn how world-famous events affected ordinary people like us. Names of former residents such as Henry Downing, Elizabeth Witham and Paul Paget do not loom large in the history books but they nonetheless have incredible stories to tell: the first was an eyewitness to the English Civil War and the Great Plague of 1665; the second was a key figure in the foundation of the Methodist movement; and the third was responsible for saving some of London’s most iconic buildings after the ravages of the Second World War. It is hoped that their stories, along with many others, will go some way to prove that every property in Britain has its own, unique history – you just have to look for it. Even twenty-first-century houses stand on land as old as time itself that holds myriad secrets waiting to be uncovered.

Today, public interest in Britain’s architectural heritage is at an all-time high but, nevertheless, not a month goes by without a much-loved building being sacrificed in the name of progress. As The Oldest House in London shows, it is not only mansions and palaces that have extraordinary histories. Homes built for ordinary people can be equally fascinating. It is up to us to preserve the buildings we love by exploring their past and, most importantly, divulging their secrets to others.

1

Land Grab

On a cool May morning in 1538, as the sun rose over the rooftops of London, Brother John Forest was dragged from his bed, dressed in a coarse woollen shift and thrust down the steps of the Franciscan friary in which he had been under house arrest. A horse stood waiting in the street, a rough wooden hurdle trailing behind its haunches. Forest was thrown to the ground, strapped to this wheel-less carriage and with a sharp crack of a whip, the horse took off through the streets of London.

Being dragged through the dung-ridden, filthy thoroughfares was just the start of John Forest’s ordeal. When the grim spectacle reached the outer precincts of St Bartholomew’s Priory, the horse was forced to slow in order to make its way through a large and rowdy crowd that had congregated outside the priory gate. Once at the centre of the mob, the full horror of the scene unfolded before John Forest’s terrified eyes. A high scaffold had been erected on which sat the city’s noble elite, watching in keen expectation. A few feet in front of this grandstand, gallows rose ominously above the crowd. Forest was untied from the hurdle and strong chains were wrapped around his waist and arms and then slung over the top of the gallows. A sharp tug on the end of the chains elevated him several feet off the ground and, as he dangled helplessly in mid-air, Hugh Latimer, the Bishop of Worcester, pushed his way through the throng, Bible in hand. For almost an hour, the bishop beseeched Forest to renounce the Pope and accept King Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the English Church. Despite knowing his dreadful fate was just minutes away, Forest refused to listen and retreated into mute prayer while, beneath him, a bonfire of hay bales and kindling was assembled.

When the Bishop of Worcester had finished his long diatribe, the crowd fell silent, knowing that this was John Forest’s last chance to save himself from the horrors to come. But no words passed his lips as torches were thrust into the bales. As the flames rose Forest grabbed a ladder propped against the gallows and to this he clung in excruciating pain as the conflagration slowly consumed him.

The dreadful execution of John Forest took place just as Henry VIII’s opprobrious Dissolution of the Monasteries was about to swing into full effect. By the time it was over, hundreds of England’s religious houses had been swept away, their valuable land and property seized by the king and his inner circle. The Dissolution was effectively the biggest land grab since the Norman Conquest. It transformed the landscape of England and, had it not happened, 41–42 Cloth Fair may never have been built.

The events that paved the way for the creation of 41–42 Cloth Fair began way back in the 1120s when an extraordinary man named Rahere founded the Priory and Hospital of St Bartholomew at Smithfield. Rahere’s life was split into two distinct chapters. His early years were spent at the court of Henry I, where he used his considerable charm and keen intellect to become a close confidante of the king. However, as he approached middle age, he began to tire of the shallow frivolity of palace life and rejected its earthly pleasures to become a canon at St Paul’s Cathedral.

Shortly after entering the Church, Rahere embarked on a pilgrimage to Rome, where he fell gravely ill. As he lay in a semi-delirious state, he vowed that if he survived, he would devote the rest of his life to caring for the sick and poor, for whom he would found a hospital. Miraculously, his prayers were answered. The fever subsided and he returned to London, where he immediately set about keeping his vow. Taking full advantage of his affluent and influential contacts at the royal court, Rahere persuaded the king to grant him a large tract of Crown land just outside the city wall at Smithfield, inauspiciously adjoining a public execution site. He then embarked on the monumental task of building a hospital and priory to accommodate the monks and nuns who would act as staff. The complex was completed in 1123 and dedicated to Saint Bartholomew.

Although St Bartholomew’s Hospital is now one of Britain’s oldest medical institutions, its early years were fraught with financial difficulties. The majority of patients came from the most deprived sphere of London society and they had no means of paying for their care. Consequently, the hospital relied solely on charity and just ten years after its foundation the coffers were running dry. Faced with imminent closure, Rahere appealed to the king for help and to his intense relief was granted a lifeline that would ultimately result in the development of the street now known as Cloth Fair. In 1133, a royal charter was drawn up for an annual fundraising event in the grounds of the priory on the feast day of St Bartholomew (24 August).

At first Bartholomew Fair admitted any type of trader, but as the years passed it became especially popular with dealers in silks and wool, which earned it the sobriquet ‘Cloth Fair’. Over the next 200 years the Cloth Fair became an important event on Britain’s commercial calendar. Every August the land on which 41–42 Cloth Fair would eventually be built was given over to densely packed wooden stalls on which eager traders displayed a dazzling range of fabrics designed to catch the eye of discerning tailors and drapers.

However, by the 1300s the fair was becoming a victim of its own success. Keen to make as much money as possible out of the event, the priory began to rent pitches to any trader prepared to pay the fee. Consequently, stallholders selling fine cloth had to contend with the rowdy distractions of beer vendors and street entertainers performing to crowds of excitable onlookers, many of whom had no connection to the cloth trade. In addition, numerous traders of questionable reputation began to frequent the fair, selling inferior goods and using very short yardsticks and dubious scales.

Inevitably, the sheer volume of people at the Cloth Fair – and the amount of cash that was changing hands – also attracted London’s criminal element, who silently darted among the throng relieving unwitting visitors of their valuables whenever they got the opportunity. By 1363, pickpockets and conmen had become so troublesome that a group of influential cloth merchants threatened to boycott the fair unless matters improved. In response, the Corporation of London dispatched constables to keep the thieves at bay and weights and measures men to check that goods were being sold honestly. The Drapers’ and Merchant Taylors’ Companies also sent officials to test the quality of the merchandise and any miscreants were swiftly dealt with by the Pie Powder Court – a corruption of the French ‘pieds poudrés’, referring to the dusty feet of itinerant traders – which met daily at St Bartholomew’s Priory.

Despite problems with law and order, the Cloth Fair successfully funded the good work of St Bartholomew’s Hospital for 400 years. In the meantime, the priory grew in both size and wealth. By 1500, the complex occupied a roughly triangular island site separated from its hospital by a narrow thoroughfare known as Duck Lane (now Little Britain).

Like many other religious houses, St Bartholomew’s Priory was a self-contained community. At the southern tip of the site lay Bartholomew Close – a sunny green with a deep well at its centre – bordered on two sides by large, timber-framed houses occupied by merchants whose rental payments swelled the priory’s coffers. Beyond the close were the imposing redbrick domestic quarters of the priory, including a spacious dormitory for the monks, an infirmary with adjacent chapel, a long refectory and a kitchen complete with its own garden stocked with fruit trees, herbs and vegetables.

Further north were two open squares – one containing a burial ground, the other a quiet garden leading to the prior’s house. This was the largest dwelling in the complex and it was connected via a galleried walkway to the centrepiece of the estate – the Church of St Bartholomew the Great. By 1500, the church’s twelfth-century nucleus had been extended to form a truly magnificent cruciform edifice. At its head, a stone chapel dedicated to the Blessed Virgin overlooked a small green and the parish burial ground. Beyond, the lofty choir and presbytery contained the altar and Rahere’s brightly painted tomb, while an enormous nave stretched westwards to the church’s grand entrance at West Smithfield.

Next to the Smithfield gateway lay the entrance to the fairground and the priory’s laundry – a small, L-shaped building bordering a large, square expanse of grass on which the washing was pegged out to dry. Known as ‘Launders Green’, this open space would later become the site of 41–42 Cloth Fair.

There is little doubt that the Priory of St Bartholomew the Great was one of the medieval city’s most impressive enclaves and the annual fair was renowned throughout the land. However, as the sixteenth century unfolded, events occurred that would leave the historic site in ruins.

By the time Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509, England’s religious houses were in disarray. The Church was the second largest landowner in England (after the Crown) and its monasteries, abbeys and priories possessed priceless artefacts. However, over the centuries some religious houses had been corrupted by their vast wealth and instead of using it to benefit the community, they devoted huge sums to the earthly pleasures of wine, women and song. Clearly reorganisation was desperately needed and the king was the one person with the power to bring it into effect. Unfortunately, it transpired that his agents were just as corrupt as those they sought to reform.

The initial aim of Henry VIII’s Reformation was purely to restore order and piety to the most self-indulgent religious houses. In 1519, the king instructed his Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey, to launch an inquiry into the most notorious establishments. Twenty-nine were found to be utterly corrupt and so Wolsey shut them down, employing Thomas Cromwell (then a young and ambitious attorney) to handle the disposal of their assets. Part of the proceeds were used to found Cardinal College (now Christ Church) in Oxford and a second college in Wolsey’s home town of Ipswich. The remainder went into the royal purse and, in doing so, sowed seeds of avarice in the minds of the king and his advisors.

In the meantime, Cardinal Wolsey’s attempts at stamping out corruption in the English Church opened the floodgates of public resentment. Tenants across the country complained of the astronomical rents charged by their ecclesiastical landlords and general opinion held that at least some of the monasteries’ enormous wealth should be diverted to poor relief and education. In 1528, Simon Fish published an influential tract entitled A Supplication for Beggars, in which he claimed that England’s corrupt religious houses were run by ‘ravenous wolves’ responsible for ‘debauching 100,000 women’. Although his argument was crude, it represented the popular view.

As religious dissatisfaction grew, Henry VIII began to take a keen interest in the growing Protestant movement in Europe and when the Pope failed to nullify his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he contentiously severed ties with Rome, declaring himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England. The events that followed would almost totally destroy England’s ancient monastic system.

In 1534, Henry launched another inquiry into England’s religious houses, this time led by Thomas Cromwell, who was instructed to assess the wealth of each establishment and investigate allegations of malpractice. Sensing an opportunity to assert the king’s religious authority and swell the royal coffers in one fell swoop, Cromwell assembled a team of commissioners and instructed them to make the most of any misdeeds they uncovered.

Their reports, which were published as the Valor Ecclesiasticus in 1535, did not disappoint. According to the commissioners, England’s monasteries were veritable dens of iniquity. William Thirsk, head of Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire, was accused of stealing church treasures, wasting his estate’s resources and using donations to hire prostitutes. The canons of Leicester Abbey were said to be indulging in sodomy and the abbot of West Langdon was branded ‘the drunkenest knave living’. Nuns were not above reproach either; two of the supposedly celibate sisters at Lampley Convent were found to have nine children between them.

Although corruption was widespread, Thomas Cromwell initially concentrated his efforts on small houses that could offer little resistance. Thus, the resulting Suppression of Religious Houses Act (1535) stated, ‘The manifest sin, vicious carnal and abominable living is daily used and committed amongst the little and small abbeys, priories and other religious houses of monks, canons and nuns where the congregation of such religious persons is under the number of 12 persons.’ However, as the huge extent of monastic riches became clear, Cromwell’s campaign snowballed. Within months, every religious house in England was affected by the events now known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The Dissolution began in earnest in March 1536 and progressed with frightening speed and efficiency. Fearing that valuable possessions would be spirited away before they could be seized, the king’s bailiffs quickly descended on abbeys, priories and nunneries across the land and took away anything of value, from precious altarpieces to the lead on the roof. In the meantime, all income from monastic estates was diverted to the Crown. In order to oversee this unprecedented rape of England’s religious houses, Thomas Cromwell established the Court of Augmentations and appointed as its head one Richard Rich – the man who was destined to own the land on which 41–42 Cloth Fair would be built.

Richard Rich was ambitious and greedy in equal measure. Born in the London parish of St Lawrence Jewry in around 1496, he initially trained as a lawyer and used his cunning, keen intellect to work his way up the legal ladder, eventually becoming Solicitor General in October 1533. In this post, he viciously persecuted any members of the Church who refused to accept Henry VIII as Supreme Head and looked on with indifference as John Forest horrifically burned to death outside St Bartholomew’s Priory in 1538.

Richard Rich’s vindictive streak was only exceeded by his sycophancy towards the king. After being made Speaker in Parliament, his opening speech compared Henry VIII to the sun, which ‘expels all noxious vapours and brings forth the seeds, plants and fruits necessary for the support of human life’. His biographer, A.F. Pollard, described him as ‘the most powerful and the most obnoxious of the king’s ministers’. Nevertheless, his working partnership with Thomas Cromwell proved devastatingly effective during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. By the time the purge was over, Richard Rich had acquired a fortune from the spoils, including the estate of St Bartholomew the Great.

The acquisition of St Bartholomew’s required a long and devious negotiation with distinctly shady undercurrents. The priory could not be closed on the grounds of being corrupt as the adjacent hospital was proof that any profits were being put to good use. Instead, Thomas Cromwell and Richard Rich were forced to play a long game that required some clever tactics.

Their chance came when the priory’s head, William Bolton, became gravely ill. With no time to lose, Cromwell made contact with Robert Fuller, the abbot of Waltham Holy Cross, who also happened be a commissioner on the Valor Ecclesiasticus. Fuller had already proved he was open to bribery by handing over some of Waltham Abbey’s land to the king in return for personal reward and so the two men entered into a verbal agreement to systematically dispose of St Bartholomew’s estates in a similar manner as soon as they had the chance.

Prior Bolton died soon after their meeting and just days later Fuller wrote to Cromwell asking him to settle ‘this matter for the house of St Bartholomew’, reiterating that his palm would be greased in return. ‘Such matters shall be largely recompensed on my part, not only in reward for your labours, but also for such yearly remembrance as you shall have no cause to be sorry for.’ Thus, Robert Fuller became the new prior of St Bartholomew the Great on the understanding that the priory would be relinquished whenever it pleased the king.

Although he was little more than Thomas Cromwell’s puppet, Robert Fuller was at least benevolent to his underlings. During his time as prior of St Bartholomew’s he took pains to ensure that his canons would receive pensions once the priory ceased to exist. He also looked after the priory’s employees. For example, over at Launders Green, Fuller made a point of recording that resident laundryman John Chesewyk and his wife Alyce had signed an agreement to launder all the priory’s linen and take responsibility for any lost or stolen items. In return, they received wages of £10 a year and a rent-free house in the priory close along with a gallon of ale and a ‘caste’ of bread every Friday. This agreement would prove invaluable when the Chesewyks came to claim compensation after the priory’s inevitable closure.

St Bartholomew’s finally ceased to exist as a priory on 25 October 1539 and Richard Rich’s Court of Augmentations immediately set about stripping the buildings of their valuables. Auditor John Scudamore was instructed to ‘make sale of bells and superfluous houses and have the lead melted into plokes and sows, weighed and marked with the king’s marks’. Five of the bells were sold to the neighbouring Church of St Sepulchre but five others remained in situ, probably because local residents argued that they would be put to parish use in the future.

The priory’s plate, jewels, vestments and cash were taken to Sir John Williams, Master of the King’s Jewels, who happened to live in Bartholomew Close. Some of this treasure was subsequently sold to the Royal Mint at the Tower of London. Meanwhile, the redundant parts of the priory complex were dismantled. The nave was, in the words of Henry VIII, ‘utterly taken away’, and its site was converted into the parish burial ground. The chapel was also removed and thus the once great Priory of St Bartholomew was reduced to a parish church, with services conducted in the twelfth-century choir.

As had been agreed with Thomas Cromwell, the canons and staff of the priory received compensation for losing their livelihoods. The day after the official closure, the Court of Augmentations granted the canons handsome pensions: Robert Glasier, the sub prior, received £15 a year; the senior canons (William Barlowe and John Smyth) got an annual allowance of £10 13s 4d apiece; and the junior canons received sums ranging from £5 to almost £7 a year. The Chesewyks at Launders Green also received an ‘annuity’, the value of which was not specified.

Unsurprisingly, the duplicitous Prior Robert Fuller benefited most from the Court of Augmentations’ bequests. He was granted the priory’s share of the profits from the annual fair along with all the real estate in the complex, with the exception of the prior’s house, which Richard Rich had earmarked for himself. However, Fuller did not enjoy his share of the spoils for long. Just a few months later, he died suddenly from causes unknown.

Although there is no evidence that Richard Rich had any involvement in Robert Fuller’s death, he certainly took advantage of it. Many of the houses in Bartholomew Close were quickly let to his cohorts at the Court of Augmentations and, by 1544, Rich was ready to buy the whole complex. In preparation for this, he instructed a surveyor to produce an inventory that was used to calculate ridiculously low values for the property. For instance, valued at just £6 was the old prior’s house, along with the priory’s halls, chambers, chapel, kitchen, buttery, gallery, dormitory, cloister, refectory and numerous outbuildings.

Although the valuation of Launders Green, other buildings in the complex and the annual proceeds of the fair were more sensible, Rich was able to acquire the entire site for just over £117.

The closure of St Bartholomew’s Priory left the adjacent hospital facing ruin, as it now had no form of income. This problem was shared with all of London’s hospitals that had traditionally been attached to now defunct religious establishments. As their future hung in the balance, the people of London expressed grave concern that if the hospitals closed the patients would be forced out into the streets, spreading disease and death in their wake. This very real threat was finally addressed in 1546 when Henry VIII granted St Bartholomew’s, along with St Thomas’s, Bridewell and Bethlem Hospitals, to the Corporation of London on the understanding that the city would pay for their maintenance.

Although St Bartholomew’s Hospital survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the bustling trade fair that once funded its work did not. By the time Elizabeth I acceded to the throne in 1558, improvements in England’s roads and modes of transport meant that London’s cloth merchants found wider markets for their goods.

As a result, the old Cloth Fair completely lost its original purpose and degenerated into a lawless and drunken carnival that stretched over a fortnight. The look of the ancient fairground also began to change during Elizabeth’s reign. In 1567, Richard Rich died and the land passed first to his son and then to his grandson, Robert. Eager to earn more from the site than just the proceeds of the annual August festivities, Robert Rich began issuing building leases on the land in 1583. Development of the fairground began and, by 1598, John Stow noted in his Survey of London:

Now … in place of booths within [St Bartholomew’s] churchyard – only let out in the Fair time, and closed up all the year after – be many large houses built, and the north wall towards Long Lane taken down, a number of tenements are erected for such as will give great rents.

The Rich family profited from the spoils of St Bartholomew’s Priory for three generations but ultimately Richard Rich’s carefully forged links with royalty proved to be a poisoned chalice. By the 1630s, public mistrust which once had been directed at England’s religious houses now turned towards the Crown and the Rich family’s loyalty to the king was severely tested. However, shortly before the situation spiralled into turmoil and violence, 41–42 Cloth Fair was built.

2

The Eagle & Child

The Oldest House in London is Built

Richard Rich’s carefully tended relationship with the Tudor dynasty was successfully maintained by his grandson, Robert. However, Elizabeth I’s death heralded a new era. In 1603, James I (who had reigned as King of Scotland since 1567) acceded to the English throne. Keen to curry favour with the new monarch, Robert Rich lost no time in introducing him to his 13-year-old son, Henry, who made an instant and lasting impression on the middle-aged monarch. By all accounts, young Henry’s ‘features and pleasant aspect equalled the most beautiful of women’ and were combined with a personality described by the chronicler Clarendon as ‘a lovely and winning presence, to which he added the charm of genteel conversation’. James I soon became infatuated, showering him with gifts, usually of the monetary variety – the historian James Granger claimed that the king ‘wantonly lavished £3,000 upon him at one time’.

The precise nature of Henry Rich’s relationship with James I is unproven, but there is evidence that he may have cynically exploited the ageing monarch’s infatuation. In 1847 the American journalist Eliakim Littell declared, ‘From the dawn of his youth, true to his ancestral characteristics, Henry Rich was a selfish politician’, adding that his handsome countenance concealed a dark heart. ‘In private life he was violent and haughty; nay more, he was a man of utmost selfishness, unmitigated by any of those loftier qualities which sometimes, coupled with a fiery, overbearing disposition … will not permit us quite to hate.’ Walter Scott’s Secret History of the Court of James I went further, stating, ‘Rich, losing that opportunity his curious face and complexion afforded him, by turning aside and spitting after the king had slabered his mouth.’

Whatever the truth of his association with the king, Henry Rich prospered at the royal court and in 1612 his social status was elevated further when he announced his engagement to Isabel, the daughter and heir of Sir Walter Cope – an immensely wealthy landowner who presided over his vast estates from an enormous mansion known as Cope Castle, the grounds of which stretched across the modern west London enclave of Kensington.

Delighted to be forging links with the influential Cope family, Henry’s father Robert rewarded him with the valuable deeds to the St Bartholomew estate. Determined to squeeze as much profit as possible from his wedding gift, Henry resolved to develop its last available plot of land – Launders Green.

Although it promised to be a lucrative speculation, Henry Rich’s plan for Launders Green received a lukewarm reception from both the locals and the City’s Court of Aldermen, who had long since felt that the precinct of St Bartholomew’s was becoming dangerously overcrowded. Aware that his new development had its detractors, Rich offered some reassurance by promising to issue strict, thirty-one-year leases forbidding multiple tenancy. This had the required effect and the project was given the green light by the authorities.

Once the fear of overcrowding had been allayed, Henry Rich set about designing a neat square of eleven tall townhouses on Launders Green. As was common practice at the time, each property served as a live/work unit. Subterranean storage cellars led up to an open-fronted room at street level that could be used by the inhabitants as either a workshop or a retail premises. Keen to maximise his return on these shops, Henry Rich stipulated that they had to be vacated each year at fair time so he could let them (for hefty rents) to traders. In order to minimise the inevitable disruption this would cause for the inhabitants, he incorporated staircases in Launders Green’s inner courtyard that gave direct access to the living quarters without going through the shops. The first storey of these airy chambers comprised, in modern estate-agent parlance, ‘reception rooms’ in which the inhabitants relaxed, ate and entertained guests. On the floor above, similarly proportioned rooms provided sleeping quarters while further bedrooms and servants’ accommodation were found in the steeply pitched garrets.

Building work on Launders Green began in 1613. Unusually for the time, wattle and daub walls were eschewed in favour of bricks, which were almost certainly crafted locally. Ever since Dutch brickmakers had opened a field near reconstruction work at London Bridge in 1404, the practice of creating brickfields close to development sites had become common and rather neatly resulted in buildings being created from the earth on which they stood.

By the time Launders Green was developed, brickmakers were capable of producing bricks in different shades, which could be used to create attractive geometric patterns on frontages. However, although this style was popular in Europe, the brickwork on English houses was often left plain and embellished with intricate plasterwork designs instead. The Worshipful Company of Plaisterers (plasterers) was granted its first charter by Henry VII in 1501 and, over the following century, elaborate plaster mouldings became a popular form of house decoration, both inside and out. Examples still survive today across Britain – Canonbury House (once part of St Bartholomew’s Priory’s extensive portfolio) has ornate sixteenth-century plasterwork, as does the Charterhouse in nearby Charterhouse Square.

Over at Launders Green, it seems unlikely that Henry Rich would have gone to the expense of decorating his rental properties with expensive plaster designs. However, tantalising illustrations published in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1800 reveal that some of Cloth Fair’s oldest buildings did indeed possess them. The jettied upper floors of a butcher’s shop are shown sporting four gargoyles, and a townhouse – possibly one of the Launders Green houses – is embellished with three huge plaster casts of flowers and animals, measuring around 6ft in height.

While their walls and foundations were built of brick, the floors of the Launders Green houses were almost certainly made from broad and sturdy oak boards. This durable wood was also used to panel interiors of the period and many examples survive today, their light honey brown surfaces blackened by centuries of smoke. Elsewhere in the houses, elm was probably used for doors and window shutters while fences around the construction site would have been made from wicker hurdles of woven hazel, alder and willow.

Transport logistics meant that wood used in house building often came from local estates, so Henry Rich’s land at Kensington may well have yielded the timber for his properties at Launders Green. However, if no local supply was available, a large yard at St Benet Woodwharf in the City stocked Estrich (or Eastland) boards from the Baltic. The standard 8ft 6in length of these timbers dictated ceiling heights on timber-frame buildings and subsequently became the standard height for rooms in domestic houses of the period, even those built of brick or stone.

Protecting the Launders Green houses from the elements were steeply pitched, tiled roofs and wooden pentices, which acted as awnings over the shop front and were a useful place to hang banners advertising the goods inside. However, as traders competed to make their banner the most visible pentices grew to dangerous proportions and jutted so far into the street that unobservant horse riders were regularly knocked off their mounts. Thus, by the time Launders Green was developed, the City authorities had decreed that all pentices had to be raised at least 9ft from street level.

The principal features inside the Launders Green properties were undoubtedly the fireplaces. In the early 1600s fires were used for heat, light and culinary activities and, even on a hot summer’s day, at least one hearth would be lit in any given home. The paramount importance of fires led to the curious tradition of placing a shoe inside the chimney stack, either on a ledge or in a purpose-built cavity behind the hearth. The sheer number of shoes discovered in seventeenth-century chimneys make it extremely likely that some were hidden inside the Launders Green houses, but today we can only guess at why they were put there. It may be that builders left them as a sort of personal signature or they may have been installed by the occupants as a fertility talisman – the ancient nursery rhyme, ‘There was an old woman who lived in a shoe’ tells the story of a home overrun with children, shoes and boots were tied to the back of honeymoon vehicles, and Lancashire women who wanted to conceive often wore the shoes of someone who had recently given birth. However, whether these traditions have any connection to the mysterious shoes in chimneys is a moot point.

Obscure superstitions notwithstanding, the Launders Green houses were completed in the winter of 1614 and Nos 41–42 Cloth Fair – today the only surviving section of the square – became part of London’s cityscape. Now that the last piece of available land at St Bartholomew the Great had been developed, Henry Rich was eager to discover how much his estate was worth. With this in mind, he employed surveyor Gilbert Thacker to visit the site and compile a list of every building, its value and the name of the leaseholder. Amazingly, Thacker’s survey survives and today it provides a fascinating and unique snapshot of Cloth Fair at the beginning of the 1600s. It also reveals that, from the outset, today’s 41–42 was let as one house containing ‘two cellars, two shops, four chambers and two garrets opening both front and west’. Its first tenant was a man named William Chapman.

Details of ordinary people who lived in England during the early 1600s are frustratingly scant. However, William Chapman had sufficient personal wealth to leave a very detailed will from which glimpses of the man can be snatched. By the time he purchased 41–42 Cloth Fair, he was probably in his late forties or early fifties, a partner in a successful business with a gentleman named John Martin and married to Joan. There is no evidence that he had any children but members of his extended family, including his ‘kinswoman’ Frances Fullwood and nephew Robert Chapman, lived nearby.

It transpired that William Chapman had innovative plans for his new house. After acquiring a thirty-one-year lease from Henry Rich on 14 December 1614, he set about converting the ground floor and cellars into an alehouse to serve the busy local area.

Seventeenth-century alehouses offered victuals, warmth and a convivial escape from the trials of everyday life. The beverages on offer were similar to those available in modern pubs, with the notable exception of wine, which since 1553 had been restricted to specially licensed taverns. As their name suggests, alehouses traditionally specialised in ales, many of which were home brewed. However, by the time William Chapman opened his establishment on Cloth Fair, ale sales were rapidly being overtaken by beer, which was easier to produce and could be stored longer without deteriorating. Three strengths were available, the most potent being ‘double beer’, which sold for around 20s a barrel and was marketed using thrillingly ominous brand names such as ‘Dagger’ and ‘Pharaoh’. ‘Middle beer’ was a cheaper, more diluted brew that could be purchased for around 8s a barrel and ‘small beer’ was so weak that it could be consumed by children – the term survives today, describing something of little consequence.

In addition to ale and beer, early seventeenth-century alehouses often served ‘aqua vitae’, a devilishly strong spirit distilled from ale dregs that was either made in-house or purchased from a local distillery. The drink was so potent that it was said that just one pint of the stuff could send ten men into a stupor. Consequently, aqua vitae proved immensely popular and over the course of the 1600s it was gradually refined into the beverage we now know as gin.

Although they served a similar purpose to the modern pub, the drinking rooms of alehouses were sparsely furnished and decorated. As they possessed no bar, drinks were dispensed direct from the barrel into a vast array of vessels including pewter tankards, wassail bowls and wooden cups known as noggins. The cheaper ales and beers were served in earthenware pots or leather-handled wooden cans lined with pitch, known as black jacks. Most of the drinking vessels held either a pint or a quart (2 pints) but larger versions – some holding up to 2 gallons – were available for communal drinking.

Another crucial feature of the seventeenth-century alehouse was the hearth, which was especially valued by poorer customers who could not afford to heat their own homes. Set around it were simple trestle tables, benches, stools and perhaps a chair or two. A few upmarket alehouses also provided reading matter in the form of a Bible on a lectern, but in an age when literacy was low this was by no means essential. Walls were usually left plain, although some alehouses decorated them with murals, often depicting biblical stories such as Daniel in the lion’s den.

Officially alehouses were supposed to have just one entrance and exit. However, numerous contemporary court hearings record instances of customers creeping out of back doors to escape creditors, angry spouses or the local constable. Outside the front door, alehouse keepers were required to hang a lantern and a sign that could be understood by any passer-by, regardless of whether they could read. Originally these signs were known as ‘ale stakes’ and comprised a removable pole that was placed into a slot whenever the ale was ready to serve. If a house sold wine, a ‘bush’, or bundle of twigs, was hung on the end. However, as alehouses grew in number and home brewing was superseded by wholesalers, alehouse keepers sought to distinguish their business from competitors by creating bespoke signage. For his house at 41–42 Cloth Fair, William Chapman chose a particularly cryptic name – the Eagle & Child.

The meaning of the Eagle & Child was probably derived from an ancient legend concerning Alfred the Great. During a hunting trip, the king was distracted by a baby’s cries and, on further investigation, his men discovered a boy dressed in purple and wearing gold bracelets (the mark of Saxon nobility) in an eagle’s nest. Alfred named the child Nestingium and took him into the royal household. During the 1300s, the legend was appropriated by a nobleman named Sir Thomas Lathom, probably to legitimise a son born out of wedlock. According to this later story, the infant was found in an eagle’s nest in Lathom Park and adopted by Sir Thomas as his heir. Eventually a descendant of the child married into the Stanley family and, to this day, the eagle and child appears on the Stanley coat of arms. That said, there is no evidence that William Chapman had any connection to the Stanley family and the legend was not well known when he opened his alehouse on Cloth Fair.

In 1710, ‘British Apollo’ was so bemused by obscure alehouse names that he wrote the following verse:

I’m amaz’d at the signs

As I pass through the town,

To see the odd mixture –

A magpye and crown,

The whale and the crow,

The razor and hen.

The leg and seven stars,

The axe and the bottle,

The tun and the lute,

The eagle and child,

The shovel and boot.

Whatever the reason behind his choice of name, William Chapman’s Eagle & Child alehouse was a gamble. During the early 1600s, victualling was a notoriously volatile business and an estimated two out of every three alehouses went bust within five years of opening. Their failure was due to the dual threat of stiff competition and the authorities’ endless quest to combat public drunkenness.

The latter was a particular problem in the parish of St Bartholomew the Great during fair time. By 1600, the event had degenerated into a fourteen-day carnival of debauchery, the neat rows of cloth stalls replaced with puppet booths, freak shows and pop-up brothels bearing the poetic sign of a soiled dove. In 1613, Ben Jonson described the scene in his play, Bartholomew Fair: ‘The place is Smithfield, or the field of smiths, the grove of hobby-horses and trinkets. The wares are the wares of devils and the whole Fair is the shop of Satan.’ Nevertheless, any attempts to curb drinking proved unsuccessful and, by 1641, Richard Harper noted, ‘Cloth Fair is now in great request; well fare the Ale houses therein.’

Given the precarious nature of alehouse keeping, William Chapman wisely opened the Eagle & Child as a sideline rather than his main business. His wife Joan may have run the house at first, but when she died, management passed to a widowed servant named Bridget Warner. William Chapman’s will reveals that he treated Bridget with generosity and respect, but this was not always the case in alehouses of the period. Female servants in some establishments were enthusiastically encouraged or even pressured into offering ‘personal services’ to the male clientele. A seventeenth-century report from Anglesey shamelessly stated, ‘Most of our alehouses have a punk [prostitute] besides, for if the good hostess be not so well shaped as she may serve the turn in her own person, she must have a maid to fill pots.’

Although Bridget Warner was not expected to offer sex to customers, she almost certainly had to contend with a criminal element. In around 1612, Robert Harris complained, ‘Too many [alehouses] are nurseries of all riot, excess and idleness’, and court records from the period are littered with reports of alehouses being used as a criminal resort. A particularly atrocious London establishment even ran an academy for cutpurses and alehouses in Bermuda (a rookery in St Clement Danes) swarmed with ‘persons accused of murder and other outrageous offences’.

It is clear that running an alehouse was not for the fainthearted and consequently women like Bridget Warner were typically feisty characters. One of her contemporaries – Mother Bunch – was said to have a laugh so loud that it could be heard from Aldgate to Westminster, and the broadside ballad ‘Kind Believing Hostess’ recorded another formidable landlady:

To speak poor man he dares not

My hostess for him cares not

She’ll drink and quaff

And merrily laugh

And she his anger fears not.