Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

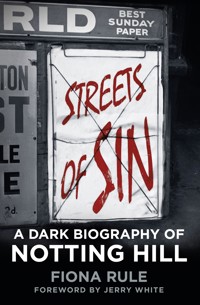

Notting Hill was not always an upmarket residential enclave and celebrity hotspot. Streets of Sin delves into the district's murky past and relates the deplorable scandals and shocking crimes that blighted the area from its development until the late twentieth century. Best-selling London historian Fiona Rule sheds new light on notorious events that took place amid the leafy streets, including the horrifying murders at Rillington Place, the nefarious career of slum landlord Peter Rachman, the Profumo affair and Britain's first race riots. She reveals what life was like in 'Rotting Hill' during its dark years when murder, extortion and disorder were everyday occurrences, and explores the price its residents have had to pay to climb up out of the ghetto.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Robert

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With many thanks to the people who helped bring Streets Of Sin to fruition, especially my agent Sheila Ableman, the staff at The National Archives, Metropolitan Archives & RBKC Archives and Mark Beynon and Naomi Reynolds at The History Press.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Jerry White

Introduction

1 The Road to Ruin

2 The Slave Owner and the Racecourse

3 The Slough of Loathsome Abominations

4 Blackout

5 10 Rillington Place

6 Tragedy

7 Street-Fighting Men

8 Rachmanism

9 ‘He’s in Love with Janie Jones’

10 Purple Haze

11 The New Bohemia

12 Gentrification

Select Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORDBY JERRY WHITE

Notting Hill! The very name holds magic for us, conjuring before our eyes those strikingly elegant terraces in white or coloured stucco at the ready-to-burst end of London’s hyper-inflated property market. With super-rich property come the people to match. Here are the Russian oligarchs and worldwide billionaires, here are the Hollywood film stars and TV entertainers, the footballers, the celebrity WAGs and fashion models, even the brightest stars of British political life from across the party divide. It was a world unforgettably celebrated in a film of 1999 called – what else – Notting Hill.

The one thing all of these people must have, it seems, is money. And the other, perhaps, is a love of London, for in part Notting Hill crystallises some of the best that London has to offer its citizens and the world. It still has its council estates that continue to give the area a diverse mix of classes, with working people and the moderately rich rubbing shoulders in street and park and local shops. Just as important, Notting Hill bears the legacy of having been in at the birth of a multicultural metropolis in the years soon after the end of the Second World War. In many ways it was the most important centre in the country of the West Indian diaspora of the 1940s and ’50s. For a generation it became the capital’s showcase of Caribbean food, music and club life. This legacy has been kept joyously alive in the Notting Hill Carnival, staged here every August bank holiday since the mid-1960s, the largest street festival in Europe, second only to the Rio carnival worldwide, and drawing in between 1 and 2 million visitors each year. Both London and Notting Hill have become even more multiculturally diverse in the last thirty years or so and we can see that in the range of food on offer in Notting Hill’s restaurants: Indian, Thai, Caribbean, Eritrean, Mexican, American, ‘International’, Italian, French, Spanish, Greek, ‘Modern European’, British – the list seems endless and probably is.

And yet. Scratch the surface, as anywhere, and there are problems. When a world-famous fashion model was reported in the week I am writing this to have had her home burgled, she was described by police as the ‘latest victim of criminal gangs targeting wealthy celebrities in Notting Hill’. The easy conjunction of criminal gangs and Notting Hill would jar with many readers, but not with Fiona Rule. For it is this darker tradition of Notting Hill that she has brought to life in her new exploration of London’s seamy side. We might think, and it’s probably true, that anywhere has its darker side to be unearthed by a sharp-eyed investigator. But what she reveals about Notting Hill will surprise many. For Notting Hill’s dark side is very dark, and runs very deep, indeed.

Even before what we think of as Notting Hill took shape in brick and slate on the open fields of North Kensington, the district was mired in filth and lawlessness. Part of it was known as ‘The Piggeries’ and for obvious reasons, the pig-keepers’ lakes of liquid manure making this the most malodorous suburb in the whole metropolis. Nearby were ‘The Potteries’, where colonies of brick makers and potters dug up the local clay and baked it in kilns, their pungent odour and black smoke adding to the district’s grime. The fields were dangerous to walk in alone at night, and violent robberies were commonplace. When building did get underway, from the 1860s in particular, the speed and cheapness with which much terraced housing was run up made part of this new suburb, though designed for a smart incoming middle class, notorious as ‘Rotting Hill’.

The land on which the piggeries and potteries had held sway, and on which gipsy encampments were a prominent feature, were also eventually developed with housing, even cheaper and worse built and more badly drained than the more prosperous streets. This western part was christened Notting Dale. By the end of the nineteenth century it was one of the most desperately poor and unruly districts of London. Here, bizarrely, was what appeared to be an East End slum at its worst, transplanted to the new smart suburbs of the west. It became for journalists and social reformers in the 1890s and for twenty years after, ‘the West-End Avernus’, or hell-on-earth. Over 4,000 people were living here at the turn of the twentieth century. The infant mortality rate in Notting Dale was such that even as late as 1896, forty-three children out of every hundred born there would die before they reached their first birthday.

Notorious Notting Dale would remain intact until just before the Second World War; sufficient of it remained in 1958 to help mobilise the worst outbreak of anti-black rioting ever seen in this country, the ‘Notting Hill Race Riots’. Close by, at 10 Rillington Place off St Mark’s Road, one of the very darkest dramas in Notting Hill’s secret past had been only recently played out. Here between 1949 and 1952, John Reginald Halliday Christie murdered five women and a baby, having killed at least two other women before moving there. He seems to have been a necrophiliac, murdering mainly for sexual gratification. Christie will forever remain the central exhibit in Notting Hill’s chamber of horrors, as he rightly does in this book.

Christie apart, Fiona Rule has been able to populate Notting Hill’s sinful saga with a memorable cast list of villains and victims. She has found confidence-tricksters, even slave traders, among the investors of Rotting Hill; there are nefarious doings, including murder, in the blackout and among the spivs of black market Notting Hill during the Second World War; we enter the world of the slum landlord Peter Rachman and meet some of his more famous contacts; we are shown the dreadful murders in the mid-1960s of young prostitutes working the streets of Notting Hill and elsewhere in west London by an unidentified man, so-called ‘Jack the Stripper’; and we learn of much else previously hidden away in these overpopulated ‘Streets of Sin’.

Through her painstaking investigation, Fiona Rule shows us one by one the skeletons hidden in Notting Hill’s darkest cupboards. It’s all a fascinating story because, as Rule memorably reveals, Notting Hill is that intriguing urban puzzle – a glitzy district with ‘a past’.

Jerry White

May 2015

INTRODUCTION

Back in the early 1990s, I found myself working in the marketing department of a, sadly, now defunct London bookshop chain. A major part of my job was to attend book launches that were organised by publishers in all manner of interesting and enticing locations. My attendance at these events was supposed to be a fact-finding mission so that I could effectively promote the books in question. However, like virtually everyone else, I generally went for the free wine.

One evening, my boss, who hated these junkets with a passion, thrust a smartly printed invitation into my hand and said, ‘There’s a cook book launch in Notting Hill tonight. It’s at the publisher’s house and I promised her that one of us would go.’ Clearly, the ‘one of us’ was going to be me.

As I sat on the Central Line train heading towards Notting Hill Gate, I realised that I was venturing into a part of London about which I knew virtually nothing. As a staunch north Londoner, my social life rarely took me further west than Marble Arch and the only thing I associated with Notting Hill was the annual carnival, which, according to the press, was so dangerous that no one in their right mind would want to go there. The train rumbled into the station, I alighted and made my way out into the sunlight. It was a glorious, late summer evening and the atmosphere as I stepped on to the broad, shop-lined thoroughfare exuded a calm that never permeated the endless hubbub of my West End workplace. I checked the address on the invitation and after consulting my A–Z, made my way towards Ladbroke Road.

On arriving at my destination, I apprehensively hovered around outside, hoping that some other guests might soon turn up so I wouldn’t have to go in alone. As I scanned the street for possible candidates, I noticed that the houses looked much the same architecturally as those in north London’s inner suburbs. However, at the same time, they were also distinctly different. My old stomping grounds of Kentish Town and Islington had more than their fair share of Victorian stucco-fronted terraces, but the houses there were often rather careworn and looked their age. The properties on Ladbroke Road could have been built yesterday, such was the standard of decoration. Their frontages were painted in a tasteful range of creams, whites, blues and pale pinks; their gardens were pristine and their front doors glossy.

As I was taking in the scene, a couple arrived and made their way up the steps to the house. Seeing my chance to enter the party discreetly, I followed them. Once inside, the property’s interior took my breath away. The great Victorian designer William Morris famously said, ‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’, and the owners had followed his advice to the letter. As I made my way down the lofty hallway, I glimpsed the front sitting room – a sumptuous retreat furnished in opulent shades of chocolate and cream. Further down the hall, a small flight of stairs led to a kitchen fitted with carved oak cabinets and a terracotta tiled floor. Delicious aromas were emanating from a large range, where hostesses were producing trays of hors d’oeuvres which they efficiently slid on to serving plates before whisking them off into the garden, where most of the guests had assembled. Nervously accepting a glass of champagne from a smiling waitress, I made my way outside.

On entering the garden, I quickly realised that most of my fellow guests had, like me, arrived alone. Consequently, it was easy to strike up conversations without feeling like I was butting into a private clique. Most of the chat took the inevitable form of polite, mundane comments about the lovely house, the beautiful weather, the generosity of the host, etc., etc. However, one conversation made me prick up my ears. ‘Of course, Christie lived just down the road from here,’ a middle-aged man idly commented as I joined a small circle of people on the lawn.

‘The murderer?’ I asked.

‘One and the same,’ he replied, before rapidly moving on to another topic.

The party continued for another hour or so before I noticed some of the guests were preparing to leave. By this stage, the warm sunlight that had filled the garden was beginning to fade and it was getting distinctly chilly. I thanked the hostess, took my complimentary copy of the cookery book (which looked fiendishly complicated) and left the party.

Travelling home on the tube, I flicked through the book I’d been given and realised that my initial suspicions were correct. The recipes were terrifyingly sophisticated. I quickly shut it and my thoughts turned to the brief conversation about the murderer, Christie. At the time, I knew little of the sordid case, but I had seen the film 10 Rillington Place, in which Notting Hill was presented as a dilapidated, poverty-stricken slum. The scenes I recalled bore absolutely no relation to the Notting Hill I had just witnessed at the party. How could one small area of London have changed so much in such a short space of time? I resolved to find out.

Once I began to research the story of Notting Hill, I quickly realised that the fine houses and neatly tended gardens now lining the district’s thoroughfares are largely a modern phenomenon. Well within living memory, many of these properties were among the most rundown in the whole of London and the grinding poverty endured by their inhabitants created an environment in which unspeakable acts of exploitation, debauchery, and even murder, were committed on a frighteningly regular basis. By the end of the 1950s, so much shame and scandal had been heaped on the area that the DailyMirror renamed it ‘Rotting Hill’.

Originally intended to be west London’s answer to Regent’s Park, Notting Hill’s fall from grace was fast, spectacular and almost permanent. It is only in the last few decades that the area has managed to wrest itself from its sordid past and finally become the upmarket residential enclave that the original landowner dreamed of creating back at the beginning of the 1800s. However, its inexorable climb out of the ghetto has come at a cost. This is the troubled story of Notting Hill, W11.

1

THE ROAD TO RUIN

The evolution of Notting Hill from a tiny, rural community to a fully-fledged inner London suburb was fraught with scandal and disaster, borne by blind ambition and greed. Back in the mid-1700s, the estate formed part of a sparsely populated, agricultural landscape that was located a good half an hour’s walk from the outer reaches of the metropolis. The land was the property of Richard Ladbroke – a hugely wealthy, but largely absent landlord who rarely visited his estate, preferring to divide his time between his mercantile business in the City and Tadworth Court, a sprawling country property near Banstead Downs Racecourse in Surrey.

Ladbroke’s estate lay by the side of an ancient thoroughfare linking London to the market town of Uxbridge. Close by, a tollgate collected funds from travellers to keep the road’s final stretch into the city navigable. Although long since vanished, the tollgate was responsible for giving the area the name by which it is known today – Notting Hill Gate.

The narrow ribbon of buildings that flanked the toll road in the mid-1700s were collectively known as Kensington Gravel Pits – a rather prosaic name given that the locality was renowned for its magnificent views and outstanding natural beauty. That said, the gravel beds were responsible for putting the area on the map. Used extensively in road building, gravel played an essential part in the development of eighteenth-century London and today, the natural resources from Kensington Gravel Pits still lie buried beneath the streets.

The eastern and western borders of Richard Ladbroke’s estate were marked by two bumpy cart tracks leading north. The easternmost track led through a patchwork of meadows to a smallholding known as Portobello Farm. This ramshackle, L-shaped building had been constructed by a Mr Adams in 1740 and proudly named after a famous sea battle that had taken place the year before, where the British captured the Portobello naval base in Panama from the Spanish.

Although it was situated quite close to the Uxbridge Road, the farmhouse possessed a distinctly remote atmosphere. A narrow front garden bounded by a low brick wall led to a sun-bleached front porch. By the side of the house, a patch of scrubland where carts and carriages could be parked was bordered by a small thicket of trees and a dilapidated fence, which led round to the back of the property, enclosing a small garden. Outside the fenced perimeter, a footpath wound past an old pond into the fields beyond, while close by, huge haystacks – themselves the height of houses – stood like monoliths amid the bucolic landscape.

The western edge of Ladbroke’s estate was bounded by the other country lane. This gravelly track, which led to a natural well used by the villagers, was known locally as Green’s Lane in memory of the Green family, who had operated a market garden there during the first half of the 1700s. Green’s Lane came to an abrupt end at the well and anyone wishing to travel further north would have to cross two large meadows before they came upon the next vestige of civilisation – Notting Barns Farm.

Owned by the wealthy Talbot family, this large and impressive edifice had long ago been the local manor house and was described by the topographer Thomas Faulkner in 1820 as ‘an ancient brick building, surrounded by spacious barns and out-houses’. To the east of the farmhouse, a large pond lay by the side of a deeply rutted cart track leading to the village of Kensal Green, about 1 mile away.

Although Richard Ladbroke’s land was surrounded by lucrative enterprises, such as the two farms and the gravel pits, none actually lay on the estate itself. Thus, he had to content himself with the comparatively small rents derived from a few houses along the Uxbridge Road and two smaller farms. One of these farms stood by the side of the toll road (on the site now occupied by the Mitre Tavern); the other – Notting Hill Farm – stood on the summit of Notting Hill. By 1800, this particular farm comprised a rather decrepit complex of dwellings, sheds, haylofts and barns that straddled a busy footpath to Kensal Green. Consequently, the Hall family, who operated the farm in the first decades of the 1800s, had to constantly contend with pedestrians and horses filing through their farmyard.

Neither Richard Ladbroke nor his son (also Richard) made any attempt to develop their Notting Hill estate, despite the fact that it lay only a couple of miles from the rapidly expanding borders of the City of Westminster. In 1794, Richard Ladbroke junior died childless and the estate passed to his cousin, Osbert Denton. Keen to preserve the family name, Richard had stipulated in his will that the Notting Hill estate had to be inherited by a Ladbroke. Thus, Osbert was compelled to change his surname.

This caveat applied again in 1818 when Osbert died, and the Ladbroke estate passed briefly to another cousin – Cary Weller – who, unfortunately, expired less than two years after receiving his inheritance. The estate then changed hands once again, this time to Cary’s younger brother, James, who, in accordance with the will, changed his surname to Weller Ladbroke and set about putting his stamp on the Notting Hill estate. His ill-conceived plans would prove to have a devastating effect on the area and would ultimately throw the little community that surrounded it into turmoil.

James Weller Ladbroke was born around 1776 – the second son of the Reverend James Weller and Richard Ladbroke’s aunt, Mary. As he was the youngest male in the family, neither James nor his parents ever considered that he would one day inherit the estate at Notting Hill and James was encouraged to go into the military, first joining the 47th Foot Regiment and then the 23rd Light Dragoons, with whom he served at Corunna and Talavera during the Peninsular War of 1808–14. In 1803, he married a distant cousin – Caroline, the daughter of Robert Napier Raikes, vicar of Longhope in Gloucestershire. The couple had one child – a daughter, whom they named Caroline – and lived in modest comfort at a country house named Hillyers, near Petworth in Sussex.

James Weller Ladbroke’s army career was unremarkable and after retiring around 1815, he spent four uneventful years ensconced at Hillyers where he idled away the hours by running the local cricket club. The sudden death of his older brother, Cary, in 1819 changed his life totally and irrevocably.

Although he had never expected to become a major landowner, James Weller Ladbroke relished his new vocation and was utterly seduced by the possibilities that presented themselves. All thoughts of the cricket club faded into insignificance as he began laying plans to develop his newly acquired land into the most ambitious luxury housing estate ever seen in Britain.

Ladbroke’s inspiration for his grand scheme was nothing less than regal. Back in 1811, the Prince Regent (later George IV) had entered into discussions with the fashionable architect John Nash, to create a palatial estate at the old royal hunting park in Marylebone. With a virtually unlimited budget at his disposal, Nash drew up a plan to rival the most opulent palaces across the globe. The huge, 500-acre park would be landscaped, and in the western section a long, curved boating lake would be created, across which the prince and his retinue could row to a series of little islands at its centre. Over on the east side of the park, a long, rectangular ornamental lake lined with avenues of trees would echo the gardens of the greatest palace of them all – Versailles. The palace building was envisaged at the centre of the park, standing amid neat formal gardens of box hedge and sweet-smelling roses. Around the perimeter of the park elegant, stucco-fronted mansions for the prince’s inner circle would be built in the latest Regency style.

Work began on the ‘Regent’s Park’ in 1818 – just one year before James Weller Ladbroke inherited his estate, and although much of Nash’s original scheme never came to fruition, the development made a huge impression on him. Heady with ambition, Ladbroke resolved to build west London’s answer to Regent’s Park on his land in Notting Hill. The only problem was, he did not have the backing of the future king (nor any other nobility), who might have added the cachet needed to attract London’s elite to an estate that at the time, was a long way out of the fashionable West End.

The fact that James Weller Ladbroke’s land was in a rural backwater rather than a royal hunting park did nothing to dampen his enthusiasm for the project. Almost as soon as he inherited the estate, he set about finding an architect who was up to the monumental task in hand, but who would not charge the exorbitant fees of John Nash. The man he chose for the job was Thomas Allason.

Allason undoubtedly possessed considerable creative talent. A student of the great Gothic revival architect, William Atkinson, he had won the Royal Academy of Architects’ silver medal in 1809, at the tender age of just 19. Five years later he travelled to Greece, and the classical architecture he found amid the ruins of the Parthenon inspired him greatly. From Greece, he travelled to Pola, a town on the Istrian Peninsula, where he produced a series of beautifully executed illustrations of the Roman ruins he saw there. These drawings were published in book form in 1819 and it is likely that this is how Thomas Allason came to the attention of James Weller Ladbroke.

Although he was undeniably a gifted architect, Allason’s career failed to reach the dizzying heights of contemporaries such as John Nash and he was forced to earn a living as surveyor to the Alliance Fire Assurance Company. This rather mundane work, combined with a lack of prestigious private commissions, meant that his fees were well within the reach of men like James Weller Ladbroke and in 1823 he was commissioned to design the estate at Notting Hill.

Allason’s plans were every bit as ambitious as his client had desired. Using Notting Hill’s most prominent and attractive feature – the hill itself – as the centrepiece, he created a plan for a wide, straight avenue (today’s Ladbroke Grove) that ran northwards from the Uxbridge Road, over the brow of the hill (straight through the old farmyard) and halfway down the other side.

An expansive circus – 1 mile in circumference – crowned the summit of the hill, bisected by the central avenue to create two enormous crescents. Allason proposed that both crescents would be lined with houses similar to those planned for Regent’s Park, but standing in private grounds of up to 5 acres. The innermost portions of the crescents contained the most unique element of the development – large, communal gardens that Allason referred to as ‘paddocks’. Barely visible from the road, these paddocks were only accessible from the houses that surrounded them. Original leases show that they were intended for the ‘convenience and recreation of the tenants and occupiers’, who could stroll and ‘demean’ themselves there. Servants were not admitted unless they were ‘in actual attendance on the children or other members of the family’.

Allason’s paddocks were a revolutionary idea that would eventually (in a scaled-down form) become a unique feature in this part of west London. Housing estates had been created around garden squares for years, but these open spaces were always at the front of the properties and usually separated from the houses by a roadway. The fact that the paddocks could be accessed directly from the residents’ back doors was novel and their inherent privacy a boon, although one wonders why a householder with 5 acres at his disposal would want communal land beyond his garden.

To the east of the hill, another, triangular development with a paddock at its centre was planned, while to the south, a road running parallel with the Uxbridge Road formed the southern boundary of the estate. This road was named Weller Street, in deference to the landowner.

While Thomas Allason was surveying the land in preparation for planning his great scheme, James Weller Ladbroke was attending to matters that were more mundane but no less important. One of the caveats in his uncle’s will specified that any building leases issued on the land could only have a duration of twenty-one years. With no funds to construct the planned estate himself, Ladbroke had to rely on selling leases to developers. However, he knew that no builder would take on a twenty-one-year contract as it was too risky. Thus, in 1821 he was compelled to force a private Act through Parliament enabling him to issue ninety-nine-year leases, which would be a much more attractive proposition to builders.

While Ladbroke was keen to start dishing out contracts, Thomas Allason urged him to progress cautiously. Although London was expanding rapidly by the 1820s, Notting Hill was still mainly farmland. The only developed area in the vicinity was the old village of Kensington Gravel Pits, but even that comprised just a few private dwellings, an ancient almshouse, a school and probably a couple of beer houses and shops (although none are mentioned in contemporary sources). Realising that luring builders out to this backwater of the metropolis was not going to be easy, Allason suggested that a test site should be developed, the majority of which he would build himself.

The land he earmarked for the trial lay on the northern edge of the Uxbridge Road, on the eastern perimeter of the Ladbroke estate. Here, Allason laid out a relatively short, L-shaped cul-de-sac, named Linden Grove (today’s Linden Gardens) and lined with modest cottages. Designed to appeal to professional families in search of a rural idyll close to London, these cottages comprised a breakfast room, a dining parlour and a kitchen on the ground floor, with three decent sized bedrooms upstairs. Outside, the properties had a wash house contained within a back yard which, in turn, led to reasonably large private gardens. In a bid to recoup his building costs as quickly as possible, Allason recommended that the cottages be rented out at the very competitive rate of just £40 per annum (rents on similar properties closer to central London could top £70 at the time.) His strategy paid off and the Linden Grove cottages quickly attracted tenants.

As Thomas Allason had intended, the Linden Grove development acted as a showcase for the Ladbroke estate. Speculative developers could now see that properties at Notting Hill could be let quickly and, although they could not achieve high rents, the comparatively low cost of the building leases made up for this.

In the early years of the 1820s, the Ladbroke estate looked like it might live up to its owner’s high expectations. With the test development complete, Ladbroke and Allason turned their attentions to their grand scheme at the top of the hill, and in 1823 they issued leases to two builders who could turn their dream of building London’s most exclusive suburb into reality.

The first building plot to be snapped up (a strip of land fronting the Uxbridge Road at the western end of the estate) was leased to Ralph Adams, a brick and tile maker who had wholesale warehouses at St Chad’s Row, Islington, and Maiden Lane in the City. Realising that it was only a matter of time before the rapidly expanding city reached Notting Hill, and impressed by Ladbroke and Allason’s aspirational plans for the area, Adams also leased a large field by the side of Green’s Lane where he set up brick kilns.

A corresponding strip of land along the Uxbridge Road at the eastern end of the estate was leased to just the type of property developer that Allason had hoped to attract with his Linden Grove experiment. Joshua Flesher Hanson was a house builder with a prestigious reputation. Over the past twenty years, he had been responsible for building some of the most impressive properties in England, including the elegant Regency Square in Brighton and Hyde Park Gate, one of the capital’s most sought after addresses.

Now they had two developers on site, Ladbroke and Allason were impatient to begin realising their dream. As an incentive to complete the building work quickly, Adams’ and Hanson’s leases stipulated that the annual ground rent on each plot would amount to just £25 in the first year, but would rise steadily in the years thereafter, reaching a ceiling of £150 in the sixth year. This strategy worked and Adams and Hanson lost little time in starting work.

The first houses to be completed gave a tantalising glimpse of what was planned on the upper slopes of Notting Hill. By 1824, elegant, stucco-fronted terraces lined the north side of the Uxbridge Road; their pillared entrances leading through to gracious, airy rooms illuminated by large, sash windows. Behind the properties, gardens stretched northwards towards the rising slopes of the hill that lay beyond. These properties, some of which still exist today, were among the finest in London and, although enticing families out of the city still proved challenging, the lower rents and large amounts of outdoor space proved popular.

With the future of the development looking promising, Allason and Ladbroke were bemused when Joshua Flesher Hanson suddenly pulled out after completing just eight of the twenty houses he was contracted to build, selling the leases on the remaining plots of land to an architect named Robert Cantwell. It transpired that Hanson had been very shrewd indeed. Just twelve months later, Britain’s economy was in turmoil and Ladbroke and Allason’s grand designs lay in shreds.

The root of the misfortune lay in national economic circumstances that are not unfamiliar today. Back in the early 1820s, when James Weller Ladbroke was formulating his plans for the Notting Hill estate, Britain was in the midst of an economic boom. The country had recovered well from the fiscal ravages of the Napoleonic Wars (which ended in 1815). An unprecedented rise in large-scale engineering projects, such as canal and road building, led to the creation of thousands of new jobs and, as the population acquired more disposable income, manufacturing ran at record levels. In this optimistic and economically buoyant atmosphere, public confidence in financial investment was high and developers like Adams and Hanson had little trouble obtaining funding for their speculative building projects. Their investors got fast returns on their money and were hungry to make more.

During the same period, on the other side of the globe, several regions in Central and South America declared independence from Spain. The new countries that emerged presented commercial opportunities, and soon the British banks were lending money to investors keen to exploit their rich resources. By April 1822, a committee of city merchants, manufacturers and ship owners announced that ‘since the establishment of Independent Governments in the countries of South America which were formerly under the dominion of Spain, an extensive trade has been carried on with them from this country, either directly, or through the medium of other places’.

In addition to trade, the British public were keen to loan funds to the newly established countries, expecting that they would receive an excellent return on their money. By 1824, proposals were circulating in the City for subscriptions to a huge loan for the ‘United Provinces of Central America’. In return, the United Provinces began making offers that seemed almost too good to be true. In January 1825, they issued an official decree to encourage foreign settlers that stated, ‘It is open to every foreigner to exercise any business he may think fit, mining included.’

On arrival, new settlers were advised to form townships, for which they obtained an agreement from a local magistrate. The regulations for the townships were as follows:

1 [Each] township must contain within it fifteen married couples at least.

2 Each married couple are to have a lot of land assigned to them.

3 A foreigner joining the township may have the same quantity of land, provided he marries within six years; and in the case of his marrying one of the native aborigines, or a woman of colour, a double portion of land.

4 Every settler may withdraw from the country when he pleases, and dispose of his property without hindrance or molestation.

5 Each new settlement is for twenty years free of all imposts whatever.

6 Exports and imports are to be free for twenty years.

7 No slaves to be admitted – the very act of introduction giving freedom to the slave.

Although many of the offers of a new life in the Americas were genuine, the market unsurprisingly acted as a magnet to con men, the most notorious of whom was an audacious Scottish adventurer named Gregor MacGregor.

In many ways, MacGregor was the perfect confidence trickster. Described by contemporaries as being strikingly handsome, his self-assured nature and ability to tell a good story made it easy for him to fool even the most cynical City traders. And like every hustler before or since, he played on people’s greed.

MacGregor first turned up in London in 1820 with his South American wife, Josefa. He made a point of frequenting the coffee shops and inns in the city, where he recounted an amazing story to anyone who would listen. MacGregor claimed to have just returned from Central America, where he had played a vital role in liberating several of the new republics from the clutches of the Spanish. In gratitude for his efforts, King George of the Mosquito Coast had apparently given him the territory of Poyais, a 12,500-square mile principality, 40 miles up the Black River in the Bay of Honduras.

MacGregor – who had styled himself the Cacique (Chief) of Poyais – waxed lyrical about his country, which reputably had acres of fertile land, gold and silver mines, a well-established infrastructure, friendly inhabitants (many of whom were descended from British settlers in the 1730s) and even the beginnings of a democratic government. In truth, the land was an uninhabitable jungle.

The London merchants took to MacGregor immediately, and he and his wife soon became the toast of the town. The lord mayor even organised a special reception for them at the Guildhall. MacGregor took full advantage of this, and after his sojourn in London he and his wife travelled to Scotland, where he played the same scam. Soon, investors were queuing up to invest in Poyais and MacGregor began to draw up deeds of sale for land there at the extremely reasonable price of 3s 3d per acre. This, of course, meant that anyone could invest in Poyais and consequently, hundreds of poorly paid workers signed up to the scheme, hoping that Poyais would change their lives forever.

In order for his con to work, MacGregor had to ensure that people actually got on ships and went to Poyais. This was the most dangerous part of the deceit as he knew full well that, if anyone returned, he would be exposed. Nevertheless, by the autumn of 1822, he had arranged for two ships to take the new settlers to Poyais. The HondurasPacket left the port of London with seventy pioneers on board in September and, four months later, the KennersleyCastle departed from Leith with another 200 hopeful settlers.

Many of the families on board the ships had ploughed their life savings into their emigration, so when they arrived at the Mosquito Coast they could not believe their eyes. Far from having any sort of township, the region was virtually deserted apart from a few fishermen who lived in dilapidated shacks. The settlers frantically searched the area for the farmland and gold mines described by MacGregor, but none were to be found. By the time they fled back to the HondurasPacket, the ship had sailed. The duped colonists were now stranded in hostile territory and had to fend for themselves – a difficult task, as most of their provisions had been lost when the boat carrying them overturned.

By the spring of 1823, worrying reports about Poyais were beginning to filter back to Britain. On 13 April, a merchant in Honduras sent a letter to Lloyd’s with some very distressing news. He wrote:

Five or six of the deluded creatures whom Gregor MacGregor sent to the Mosquito Shore as settlers to his Viceroyship of Poyais arrived here about 8 days ago. Out of the 55 who arrived at one time at the shore, 9 remain. Some put to sea to reach Belize, others up the river and have never been heard of, and others died miserably where they landed, which was absolutely among mangrove trees, which they had to cut down … General Codd [the Commander-in-Chief at Belize] intends sending immediately for the remnant of another load which were sent there lately. If he does not, they must perish from exposure, if not disease.

The merchant’s letter was not the only report that found its way back to Britain. In the same month, a rescued settler in Belize wrote to his friend in Leith:

We found the country very wild and nearly covered with wood. MacGregor had told us that there was a town where we were to be landed; but we saw neither town nor inhabitants, except a few fishermen. The heat and mosquitoes were insufferable. Every one was disappointed; and all wished to get away from the place. Six of us and a woman, wife of one of the party, determined to make our escape at all hazards; and as we knew that one of the boats, which had been employed landing the stores, was lying about five miles from where we were, we resolved to seize it, put it to sea, and endeavour to make Belize, a British settlement, about 200 miles from the Black River. At 12 at night, we secretly took away from the camp as many of our articles, and as much provision as we could manage. We crossed the river in a canoe and travelled quickly, till we reached the boat. We jumped in and pushed off with a fine breeze; but when we got out from land, our boat filled with water; our provisions were all lost; and after suffering the most dreadful hardships for five days (during which time we had not a drop of fresh water and only one biscuit, which we found in the bottom of the boat), we were at length picked up by a small vessel and taken to Port Mayhoe, a place belonging to the Spaniards, and thence to Belize. The married man died on the boat before we were picked up; we were obliged to throw his body overboard. We were in a wretched condition when we arrived at Belize but were treated with the greatest kindness and humanity by a Scottish gentleman there, George Home Esq., who took us to his house and has kept us ever since. We informed the Governor of the State of the settlers at Poyais and that gentleman ordered a schooner to be got ready to ascertain the fact. When the vessel arrived at Belize, it was found that nine of the unhappy sufferers had died and the rest were all lying sick – not one able to give a drink of water to another. As many as the schooner could take were brought away. She made another trip and came off with the remainder and the stores, which were sold to defray expenses. The sick were put into the Hospital here and received every attention and assistance which could be given them; but they are dying in great numbers from the effects of their former sufferings. Were MacGregor hanged, it would not be an adequate punishment for the misery he has heaped on so many unfortunate people.

By the time the letters from Belize and Honduras arrived in London, the truth about Poyais had been exposed by sailors returning on the ships. Concerned, the government dispatched a judge named Marshall Bennett to the republic in order to establish the true state of affairs in Poyais. Mr Bennett arrived at the township on 26 April. He later told the inquiry committee that, ‘Sickness and wretchedness prevailed among the settlers to a very great extent, without the means of obtaining comforts suitable to their distressed state.’ Some of the settlers begged Bennett to take them to Belize. He took sixty-six people on his ship and then went back for more.

The evacuation of Poyais exposed Gregor MacGregor’s scam, but by then, the self-styled Cacique was long gone from British shores. He was later found in France, where amazingly, he was operating the same con. However, by this stage his notoriety was legendary and, although he tried to set up more schemes involving Poyais in the early 1830s, the public steered well clear. He eventually fled to Venezuela, where he died in 1845.

Back in London, news of the Poyais fraud made investors very wary of any schemes involving Latin America and the value of stocks and bonds began to fall dramatically as people bailed out of the market. This, in turn, created suspicion of other investments, particularly those overseas, and the market began to slide. Banks, which had been lending money at ridiculously low interest rates, began to panic as the stock market went into freefall. With pitifully low reserves, Britain’s financial institutions were suddenly terribly exposed. The vaults of one bank – Pole Thornton – were literally left empty when one of their wealthy customers withdrew £30,000 without warning. Pole Thornton was not alone. By the middle of December 1825, numerous banks in London and the provinces were desperately scrambling to refill their coffers but, for many, it was too late. Some were saved from closure when the Bank of England began issuing emergency loans but, in total, seventy banks went into liquidation.

The financial crisis of 1825 had an effect that is all too familiar to us today. The banks that survived virtually stopped issuing loans for anything bar cast-iron investments, and as a consequence, the housing market collapsed. In the years following the banking crisis, building work at the Ladbroke estate ground to a halt and for the next decade very little development took place. By 1836, James Weller Ladbroke had failed to issue any new building leases for over two years. Disappointed and embittered, he must have wondered if his Notting Hill estate was really the golden egg he had once believed it to be. Then, just as Ladbroke was beginning to despair, a man named John Whyte appeared on the scene with an interesting proposition.

2

THE SLAVE OWNER ANDTHE RACECOURSE

Around the same time that James Weller Ladbroke had inherited his uncle’s land at Notting Hill, John Whyte became heir to another, very different estate – three sugar plantations on the Caribbean island of Jamaica. The plantations, known as Cavebottom, Craighead and Windhill, had been purchased by Whyte’s father, James, in the mid-1700s, and the family quickly became rich on the sugar, molasses and rum that they produced.