9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

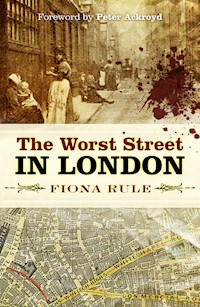

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Amid the bustling streets of Spitalfields, East London, there is a piece of real estate with a bloody history. This was once Dorset Street: the haunt of thieves, murderers and prostitutes; the sanctuary of persecuted people; the last resort for those who couldn't afford anything else – and the setting for Jack the Ripper's murderous spree. So notorious was this street in the 1890s that policemen would only patrol this area in pairs for their own safety. This book chronicles the rise and fall of this remarkable street; from its promising beginnings at the centre of the seventeenth-century silk weaving industry, through its gradual descent into iniquity, vice and violence; and finally its demise at the hands of the demolition crew. Meet the colourful characters who called Dorset Street home.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Dedicated to the memory of Desmond Rule, otherwise known as Dad.

First published in 2008 by Ian Allan Publishing

This edition published in 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Fiona Rule, 2018

The right of Fiona Rule to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9032 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Acknowledgements

It would not have been possible to write this book without the excellent staff and resources at the Public Record Office, the British Library, the Metropolitan Archive, the Newspaper Library, the Bancroft Library, Westminster Reference Library and the Old Bailey Archives. My thanks is also extended to all those who generously shared their personal remembrances of Spitalfields with me.

I would like to thank The History Press, my agent Sheila Ableman, Robert Khalastchy and Sharon Tyler for their support and enthusiasm for this project. It is greatly appreciated.

Contents

Foreword by Peter Ackroyd

Introduction

Part One: The Rise and Fall of Spitalfields

1: The Birth of Spitalfields

2: The Creation of Dorset Street and Surrounds

3: Spitalfields Market

4: The Huguenots

5: A Seedier Side/Jack Sheppard

6: A New Parish and a Gradual Descent

7: The Rise of the Common Lodging House

8: Serious Overcrowding

9: The Third Wave of Immigrants (The Irish Famine)

10: The McCarthy Family

11: The Common Lodging Houses Act

Part Two: The Vices of Dorset Street

12: The Birth of Organised Crime in Spitalfields

13: The Cross Act

14: Prostitution and Press Scrutiny

15: The Fourth Wave of Immigrants

16: The Controllers of Spitalfields

Part Three: International Infamy

17: Jack the Ripper

Part Four: A Final Descent

18: The Situation Worsens

19: A Lighter Side of Life

20: The Landlords Enlarge their Property Portfolios

21: The Worst Street in London

22: The Murder of Mary Ann Austin

23: The Beginning of the End

24: Kitty Ronan

25: World War One

26: The Redevelopment of Spitalfields Market

Part Five: A Walk Around Spitalfields

Bibliography

Foreword by Peter Ackroyd

There are some parts of London that live in perpetual shadow, their air and atmosphere tainted by centuries of poverty and sorrow. They are the streets of darkness, running like a thread through the labyrinth of London. One such street has been traced here by Fiona Rule, in a book that is part history and part reverie, part celebration and part lament.

Dorset Street, laid down in 1674, some 400 feet in length, was once unremarkable enough, but the weight of London soon fell upon it. It was part of the haunted ground of Spitalfields, a place of small and narrow houses that soon became a byword for misery. A report, written in the middle of the seventeenth century, describes the overcrowding caused by ‘poor indigent and idle and loose persons’. They became the inhabitants of Dorset Street. Fiona Rule charts the evolution of misery. By the eighteenth century the houses had become ramshackle. In the early nineteenth century they were knocked together and became what were known as common lodging houses. The relatively spacious back gardens were converted into cobbled courts so that more and more people could be accommodated. Crime and disease were rampant.

This book helps to elucidate what might be called the spiritual topography of London, whereby a certain neighbourhood actively influences the lives and characters of the people who live within it. So it is that the inhabitants of Dorset Street were described in the nineteenth century as evincing ‘the same want of hope – the same doggedness and half-indifference as to their fate’. The houses themselves suffered the same weariness; there were cases when they simply collapsed. It is a street in which people disappeared, and where their suffering became invisible to the larger world. The various tides of immigrants – Huguenots, Jews and Irish – ebbed and flowed.

But this book is not simply a London history. Fiona Rule knows the names and addresses; she gives poverty and squalor a human face. She chronicles the simple or not so simple lives of the dispossessed. That is why, for example, she throws such an unusual and intriguing light upon the crimes of Jack the Ripper. Three of his victims lived or worked in Dorset Street and one of them, Mary Kelly, was butchered there. The cry of ‘murder’ rang out that night, but no one paid the slightest notice.

Despite the attentions of journalists and philanthropists the condition of Dorset Street became worse in the last part of the nineteenth century. It was described by Charles Booth as ‘the worst street in London’, and the police would venture through it only in pairs. It was known as ‘Dossett Street’ because of the number of doss houses. It was filled with gamblers and prostitutes; dog fights and bare-knuckle fights were common. It kept up these traditions well into the twentieth century, and the last man to be murdered here was found bleeding on its stones in February 1960.

Dorset Street has now gone, part of it turned into an unlovely car park. But in twilight and night, when the shadows grow longer, it may be wise not to come too close. The old darkness may engulf you. You may hear the cry of ‘murder’, and the hands of the dead may reach out to claim you. This is a book for all lovers of London to read.

Introduction

On a cold February night in 1960, 32-year-old nightclub manager Selwyn Cooney staggered down the stairs of a Spitalfields drinking den and collapsed on the cobbled road outside, blood streaming from a bullet wound to his temple. Cooney’s friend and associate William Ambrose, otherwise known as ‘Billy the Boxer’, followed seconds later, clutching a wound to his stomach. By the time he reached the street, Cooney was dead.

The true facts surrounding Cooney’s violent death are shrouded in mystery – investigations following his murder revealed gangland connections with notorious inhabitants of the criminal underworld such as Billy Hill and Jack Spot. Newspapers suggested his death was linked to a much further reaching battle for supremacy between rival London gangs. However, the mystery surrounding Cooney’s murder is just one of the many strange, brutal and perplexing tales connected with the street in which he met his fate.

Halfway up Commercial Street, next to Spitalfields Market, stands an uninspiring office block. The average pedestrian would pay little attention to it as they passed by. But unlikely though it may seem, underneath this characterless building lies a strip of land that was once Dorset Street, the most notorious thoroughfare in the capital. The worst street in London. The resort of Protestant fire-brands, thieves, con men, pimps, prostitutes and murderers – most notably Jack the Ripper…

I first discovered Dorset Street by accident. Like many others who share a passion for this great city, its streets have always provided me with far more than simply a route from one location to another. They are also pathways into the past that reveal glimpses of a London that has long since vanished. A stroll down any of the older thoroughfares will reveal defunct remnants of a world we have lost. Boot scrapers sit unused outside front doors, hinting that before today’s ubiquitous tarmac and concrete paving, the streets were often covered with mud. Ornate cast-iron discs set into the pavements conceal the holes into which coal was once dispensed to fuel the boilers and ovens of thousands of households. On the walls of some homes, small embossed metal plaques remain screwed to the brickwork confirming long-expired fire insurance taken out at a time when fire was a much bigger threat to the city than it is in today’s central-heated and electronic-powered world. For the history enthusiast, London’s streets provide a wealth of treasure and their exploration can take a lifetime.

I had made many investigative sorties onto the streets of London before I ventured into Spitalfields, but what I found in this small, ancient district was unique and alluring in equal measure. At its centre lay the market. A far cry from the over-developed gathering place for the über-fashionable it is today, at the time of my visit it was a deserted hangar filled with a jumble of empty market stalls. Across from the abandoned market, Hawksmoor’s masterpiece, Christ Church, loomed over shabby Commercial Street, looking decidedly incongruous next to a parade of burger bars, kebab houses and old fabric wholesalers whose window displays looked as though they hadn’t been changed for at least twenty years. In the churchyard, tramps lounged around on benches searching for temporary oblivion in their bottles of strong cider.

On the other side of the church lay the Ten Bells pub. Paint peeled off its exterior walls and the interior was almost devoid of furniture save for a couple of well-worn sofas and some ancient circular tables near the window. However, despite its rather unwelcoming façade, there was something about the place that made it seem utterly right for the area. Moreover, it looked as though it hadn’t altered a great deal since it was built, so I decided to go in. Once inside the Ten Bells, the feature that became immediately apparent was a wall of exquisite Victorian tiling at the far end of the bar, part of which was an illustration of eighteenth-century silk weavers. Next to the frieze hung a dark wood board that reminded me of the rolls of honour that hung in my old secondary school listing alumni who had achieved the distinction of being selected head boy or girl. However, the names on this board had an altogether more horrible significance. They were six alleged victims of ‘Jack the Ripper’. A discussion with the barman about this macabre exhibit revealed that all six women on the list had lived within walking distance of where we were standing and may even have been patrons of the Ten Bells. They had earned their living on the streets, hawking, cleaning and when times were really tough, selling themselves to any man that would have them, often taking their conquest into a deserted yard or dark alley for a few moments of sordid passion against a brick wall. Unluckily for them, their final customer had in all probability been their murderer.

Of course, I had known a little about the career of Jack the Ripper before my visit to the Ten Bells. However, I had never previously stopped to consider the reality behind the story. The magnificence of Christ Church suggested that at one time, the area had been a prosperous and optimistic district. How had Spitalfields degenerated into a place of such deprivation and depravity that several of its inhabitants could be murdered in the open air, in such a densely populated area of London without anyone hearing or seeing anything untoward? My interest piqued, I returned home and began my research.

What intrigued me most about the Jack the Ripper story was not the identity of the perpetrator but the social environment that allowed the murders to happen. As I delved deeper into the history of the Spitalfields, I began to uncover a district of London that seemed almost lawless in character. By the time of the murders, the authorities seemed to have almost entirely washed their hands of the narrow roads and dingy courts that ran off either side of Commercial Street, leaving the landlords of the dilapidated lodgings to deal with the inhabitants in whatever manner they saw fit. The area that surrounded the market became known as the ‘wicked quarter mile’ due to its proliferation of prostitutes, thieves and other miscreants who used ‘pay by the night’ lodging houses, where no questions were asked, as their headquarters. These seedy resorts flourished throughout the district during the second half of the 1800s and were places to which death was no stranger. Even one of the landlords, William Crossingham, described them as places to which people came to die.

The sheer dreadfulness of the common lodging houses prompted me to investigate them further. During a particularly fruitful trip to the Metropolitan Archive, I uncovered the nineteenth-century registers for these dens of iniquity, which gave details of their addresses and the men and women that ran them. As I turned the pages of these ancient volumes, one street name cropped up time and time again: Dorset Street. By the close of the nineteenth century, this small road comprised almost entirely common lodging houses, providing shelter for literally hundreds of London’s poor every night of the year. Most intriguingly, I remembered that the street’s name also loomed large in the newspaper reports I had read about the Ripper murders; in fact the only murder to have occurred indoors had been perpetrated in one of the mean courts that ran off it. Dorset Street now became the focus of my research and as I uncovered more of its history, what emerged was a fascinating tale of a place that was built at a time of great optimism and had enjoyed over 100 years of industry and prosperity.

However, with the arrival of the Victorian age came an era of neglect that ran unchecked until Dorset Street had become an iniquitous warren of ancient buildings, housing an underclass avoided and ignored by much of Victorian society. Left to fend for themselves, the unfortunate residents formed a community in which chronic want and violence were part of daily life – a society into which the arrival of Jack the Ripper was unsurprising and perhaps even inevitable.

The Worst Street in London chronicles the rise and fall of Dorset Street, from its promising beginnings at the centre of the seventeenthth-century silk weaving industry, through its gradual descent into debauchery, vice and violence, to its final demise at the hands of the demolition men. Its remarkable history gives a fascinating insight into an area of London that has, from its initial development, been a cultural melting pot – the place where many thousands of immigrants became Londoners. It also tells the story of a part of London that, until quite recently, was largely left to fend for itself, with very little State intervention, with truly horrifying results. Dorset Street is now gone, but its legacy can be seen today in the desolate and forbidding sink estates of London and beyond.

Part One

The Rise and Fall of Spitalfields

Chapter 1

The Birth of Spitalfields

By the time of Selwyn Cooney’s murder, Dorset Street’s final demise was imminent. Within less than a decade, all evidence of its prior notoriety would be swept away, replaced by loading bays and a multi-storey car park. What remained of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century housing stock was dilapidated and neglected. The general impression gained from a visit to the area – especially after dark – was of a seedy, rather threatening place with few, if any, redeeming features. However, Dorset Street, and indeed the whole district of Spitalfields, was not always a den of iniquity.

A closer inspection of the crumbling, filthy houses that lined its streets in the early 1960s would have revealed elaborately carved doorways, intricate cornices and granite hearths – clues from a distant past when the area had been prosperous with a thriving and optimistic community. Its location was excellent for business as it was close to the City of London, Britain’s commercial capital, and the docks, the country’s main point of distribution. Ironically, Spitalfields’ main asset, its location, was to prove the major factor in its decline.

Back in the twelfth century, the area that would become Spitalfields was undeveloped farmland, situated a relatively short distance from London. It was known locally as Lollesworth, a name that probably referred to a one-time owner. Amid the rolling fields that stretched out towards South Hertfordshire and Essex, farmers grew produce, grazed cattle and lived a quiet, rural existence. Unsurprisingly, the area was a popular retreat for city residents seeking the calm of the countryside and many rode out there at weekends to enjoy the unpolluted air and wide open spaces.

Two regular visitors were William (sometimes referred to as Walter) Brune and his wife Rosia, the couple responsible for putting Spitalfields on the map. The Brunes appreciated the tranquillity of the area so much that they chose it as the location for a new priory and hospital for city residents in need of medicines, care and recuperation. In the mid-1190s, building work began by the side of a lane that led to the city, and by 1197 the area’s first major building was completed. The priory was constructed from timber and sported a tall turret in one corner. It must have been an imposing site in a district that was otherwise open farmland. The Brunes dedicated their creation to Saint Mary and the building was known as the Priory of St Mary Spital (or hospital). Sadly, nothing of Spitalfields’ first major building remains today, but it was known to stand on the site of what is now Spital Square. Until the early 1900s, a stone jamb built into one of the houses on the square marked the original position of the priory gate. The Brunes’ efforts were recognised 800 years later in the creation of Brune Street, which occupies an area that would have once been part of the priory grounds.

To the rear of the priory hospital was the Spital Field, which was used by inmates as a source of pleasant views and fresh air. Our modern definition of a hospital is a place that tends the sick. However, in the twelfth century, a hospital would have taken in anyone who was needy and could benefit from what the establishment had to offer. Consequently, the poor were attracted to the hospital and the Spital Field began a centuries-long reputation for being a place to which the underprivileged gravitated. By the sixteenth century, the hospital had become so popular that the chronicler John Stow noted ‘there was found standing one hundred and eight beds well furnished for the poor, for it was a hospital of great relief’.

Over the next 200 years, a small community gradually developed around the hospital. As the priory’s congregation grew, it developed a reputation for delivering enlightening and thought provoking sermons that could be heard by all who cared to listen from an open-air pulpit. At the time, religion in Britain was an integral part of everyday life and the Spital Field sermons became a popular excursion for city residents. By 1398, the sermons preached at the priory during the Easter holiday period had acquired such a reputation that the lord mayor, aldermen and sheriffs heard them. By 1488, the lord mayor visited the priory so frequently that a two-storey house was built adjacent to the pulpit to accommodate him and other dignitaries that might attend.

Such was the popularity of the Easter Spital sermons that they survived Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1534. Twenty years later, Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, travelled to the Spital Field to hear the sermons. The sermons continued to be preached outside the Spital Field until 1649 when the pulpit was demolished by Oliver Cromwell’s army.

The remainder of the Priory of St Mary Spital was not spared during the Dissolution and all property was surrendered to the Crown. In 1540, Henry granted a part of the priory land to the Fraternity of the Artillery. This land had previously been known as Tasel Close and had been used for growing teasels, which were then used as combs for cloth. The fraternity turned the land into an exercise ground, primarily used for crossbow practice. Agas’s map of London in 1560 clearly shows the ‘Spitel Fyeld’ complete with charmingly illustrated archers and horses being exercised.

By 1570, the lane next to the erstwhile priory had become a major thoroughfare known as ‘Bishoppes Gate Street’ and the area around Spital Field was redeveloped. The first new houses to be built were large, smart affairs with extensive gardens and orchards. These properties were occupied by city residents who could afford country retreats that were accessible to their place of work. As the old priory site became an increasingly popular residential area, the Spital Field was broken up and the clay beneath the grass was used to make bricks for more houses.

In 1576, excavators working in the Spital Field made a fascinating discovery. Beneath the topsoil were urns, coins and the remains of coffins, indicating that the site was once a burial ground for city folk during Roman times. Luckily for them, the excavators were not working under the same constraints that exist today and their discovery did not halt the breaking up of the field. Subsequently, the bricks made from the Spital Field clay were used to construct the first major development of the area.

While building work around the Spital Field continued, the area welcomed its first extensive influx of immigrants. During the 1580s, Dutch weavers, fleeing religious troubles in their homeland, arrived in the capital. Looking for a suitable place to live and carry out their business, they were immediately attracted to the new developments around the Spital Field. The area provided ample space to live and work, and was sufficiently close to the city for them to trade there. Thus, the area received the first members of a profession that was to dominate the area for centuries to come: weaving.

In 1585, as the Dutch weavers were moving into their new homes, Britain faced a threat of invasion from Spain. Queen Elizabeth I hastily issued a new charter for the old Artillery Ground and merchants and citizens from the city travelled up Bishoppes Gate Street to be trained in the use of weaponry and how to command common soldiers. Their training was exemplary and produced commanders of such high calibre that, when troops mustered at Tilbury in 1588, many of their captains were chosen from the Artillery Ground recruits. They were known as the Captains of the Artillery Garden. The training centre at the Artillery Ground was so efficient that it continued to be used by soldiers from the Tower of London as well as local citizens long after the Spanish threat passed.

As fate would have it, the Spanish threat of invasion inadvertently introduced the area around the Artillery Garden to a new wave of city dweller with the means to purchase a country retreat. By 1594, the entire site that had previously been occupied by the priory and hospital was redeveloped and, as Stow noted, it contained ‘many fair houses, builded for the receipt and lodging of worshipful and honourable men’. This influx of new residents, combined with the constant presence of builders, allowed inns and public houses to flourish. The Red Lion Inn stood on the corner of the Spital Field and proved to be a popular meeting place as it was considered the halfway house on the route from Stepney to Islington. In 1616, the celebrated herbalist and astrologer Nicholas Culpeper was born in this inn. While a young man growing up in rural surroundings, Culpeper developed a fascination with the healing properties of plants and flowers and, after studying at Cambridge and receiving training with an apothecary in Bishopsgate, he became an astrologer and physician. He also wrote and translated several books, the most famous being The Complete Herbal, published in 1649.

While Nicholas Culpeper was enjoying his youthful love affair with nature, businesses around the Spital Field were gradually evolving from small, individual enterprises into organised companies. One skill much in demand was the preparation of silk for the weavers, otherwise known as silk throwing. In 1629, the silk throwsters were incorporated and put together a strict programme of apprenticeship whereby no one was allowed to set up a business unless they had trained for seven years. This move raised standards of silk throwing immeasurably and weavers were assured that they would receive quality goods and services from their suppliers. The silk weavers became more organised and the quality of their work was recognised when the Weavers’ Company admitted the first silk weavers into their ranks in 1639.

The year before the silk weavers were accepted into the Weavers’ Company, King Charles I had granted a licence for flesh, fowl and roots to be sold on the Spital Field. This licence marked the beginning of a market that would exist, with only one brief interruption, on the same spot for over 300 years. The increase in traffic to and from the new market also played its part in introducing more people to the area and a thriving community was established. The Spital Field and the surrounding area became a prosperous hamlet on the outskirts of the city, populated by affluent workers, market gardeners, weavers and suppliers to the weaving industry. ‘Bishoppes Gate Street’ became a major trade route and the inns rarely had room to spare.

Chapter 2

The Creation of Dorset Street and Surrounds

In 1649, William Wheler of Datchet, a small town in Berkshire, put ‘all that open field called Spittlefield’ in trust for himself and his wife. On their death, the land was to be passed to his seven daughters. Wheler had acquired the freehold to the land in 1631 after marrying into the Hanbury family, who had purchased the freehold to the Spital Field from the Church in the late 1500s. At this point in time, the Spital Field was still very rural.

A small development of houses, shops and market stalls had sprung up along the east side of the field and two local residents named William and Jeffrey Browne had recently employed builders to develop the land they owned along the north side of the field. The resulting road was named Browne’s Lane in their honour and exists today as Hanbury Street. The south and west sides of the Spital Field remained open pasture, used by the locals for grazing cattle when it was not too boggy. In addition to the grazing areas, a series of footpaths stretched across the field, providing routes to and from the shops and market stalls. It was also considered a good shortcut to Stepney Church.

The owners of land around the Spital Field watched with great interest as the area gradually became increasingly built up. Despite the area being semi-rural, its proximity to the city ensured that new developments were highly sought after and let for decent rents. Therefore, many landowners decided to take the plunge and get the builders in. Two such men were Thomas and Lewis Fossan. The Fossan brothers lived in the city and had purchased land just south of the Spital Field as an investment some years previously. In the mid-1650s, they decided to utilise their investment and employed John Flower and Gowen Dean of Whitechapel to build two new residential streets on their land. Both streets ran east to west across the Fossan brothers’ field. The southernmost road took on the names of the builders and became known as either Dean and Flower Street or Flower and Dean Street, depending on whom you asked. Today it is known as the latter. The other road was named after the landowners and became known as Fossan Street. However, this unusual name was replaced by the more memorable Fashion Street, the name it retains to this day.

By the 1670s, development of the Spital Field began in earnest. That year, a road along the west side of the field, named Crispin Street, was finished and in 1672, William Wheler’s trustees, Edward Nicholas and George Cooke, asked permission from the Privy Council to develop the south edge of the field. Their petition was welcomed by the locals as this part of the field was apparently ‘a noysome place and offensive to the Inhabitants through its Low Situation’. What exactly was so ‘noysome’ and ‘offensive’ about the southern end of the field becomes clear when looking at an Order in Council dated 1669, where the:

inhabitants of the pleasant locality of Spitalfields petitioned the Council to restrain certain persons from digging earth and burning bricks in those fields, which not only render them very noisome but prejudice the clothes [made by the weavers] which are usually dried in two large grounds adjoining and the rich stuffs of divers colours which are made in the same place by altering and changing their colours.

Nicholas and Cooke offered their assurances to the council that ‘a large Space of ground … will be left unbuilt for ayre and sweetnes to the place.’ Their proposal was accepted, the lord mayor noting that the ‘Feild will remaine Square and open and the wettnesse of the lower parts [would] be remedied’.

Once permission had been granted, Nicholas and Cooke acted quickly. Over the next eighteen months, they issued eighty-year building leases for sites at the southern end of the field and three roads were quickly laid out: on the southernmost edge of the field, a road named New Fashion Street (later known as White’s Row), was constructed. Closer into the centre of the field, running parallel with New Fashion Street, was Paternoster Row (later known as Brushfield Street). A third road was laid in between these two roads in 1674. It was originally named Datchet Street, after the Wheler family’s place of residence, but for some reason it corrupted into Dorset Street. The road that was to become the most notorious in London had been built.

Dorset Street started life as an unremarkable road, 400 feet long by 24 feet wide, lined with rather small houses, the average frontage of which was just 16 feet. The street itself was originally intended to provide an alternative way of getting from the west to the east side of the Spital Field when Nicholas and Cooke closed some of the old footpaths. However, traffic could also travel along White’s Row and Paternoster Row when crossing the field, so it is unlikely that Dorset Street was particularly busy. It was probably just as well that the road did not experience heavy traffic, as it appears that some of the first houses were not well built. The demand for property in the Spital Field area meant that builders found it difficult to keep up with demand. Consequently, houses tended to be ‘thrown up’ and by 1675, the situation had become so serious that the Tylers’ and Bricklayers’ Company were called in to investigate. The investigators were appalled at what they found and a number of builders were fined for the use of ‘badd and black mortar’, ‘work not jointed’ and ‘bad bricks’. It seems that the first major developments around the Spital Field were destined to have a short life.