Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Editorial Verbo Divino

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Serie: Teología

- Sprache: Spanisch

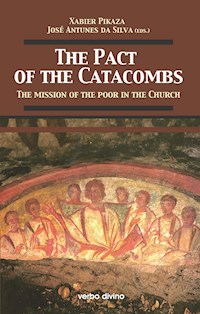

In 2015 the Catholic Church is celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second Vatican Council, a council that was a landmark in the two thousand years of the Churchs history. At the end of the Council, inspired by what was being done and said in the Council hall, some forty bishops from various countries of the world met in the Catacombs of Domitilla to sign what is today known as The Pact of the Catacombs, a text and programme that sets out the mission of the poor in the Church. The spirit of the Pact of the Catacombs has guided some of the best Christian initiatives of the last fifty years, not only in Latin America, where it had particular impact, but throughout the Catholic Church, so that its witness (its inspiration and its text) have become one of the most influential and important signs of twentieth-century Catholicism.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Índice

Presentation

1. Context

2. The text

3. Signatories

Introduction (Heinz Kulüke)

1. Church of the poor. One of the signatories of the Pact (Luigi Bettazzi)

1. The Church of the poor at the Council: the beginnings

2. The Church of the poor at the Council: the developments

3. The Church of the poor at the Council: Looking Back

2. A biblical pact. The Church of the poor in the New Testament (Xabier Pikaza)

1. A biblical pact without quotations from Church tradition

2. Biblical texts of the Pact. A vision of poverty in twelve points

3. Widening the view. Other texts on poverty

4. Conclusion. A pact open to the universal Church

3. The framers of the Pact. Origin, evolution and decline of the group called “the Church of the poor” (Joan Planellas Barnosell)

1. Introduction

2. The formation of the “Church of the poor” group

3. The group starts work: Two different views of the question of poverty

4. A document addressed to Pope Paul VI (13 Nov 1964)

5. The activities of Paul Gauthier during the last stage of the Council

6. The final stage of the Council and the Pact of the Catacombs

4. “For a Church of poverty and service”. The Pact of the Catacombs – a subversive legacy of Vatican II (Norbert Arntz)

1. The “Church of the poor” group at the Council

2. The Pact of the Catacombs of 16 November 1965

3. Effects on politics inside and outside the Church

5. The “Church of the Poor” did not Prosper at Vatican II (Jon Sobrino)

1. The Church of the poor, the Council and the Catacombs Pact

2. Conciliar innovations empowered in the Church of the poor and becoming historical fact

3. Beyond the Council and without support. “The crucified people”

6. The Pact of the Catacombs. Implications for the Church’s mission (Stephen Bevans)

1. Introduction: The Pact of the Catacombs. A Document on Mission

2. Renouncing the Appearance and the Substance of Wealth: Becoming a Credible Witness

3. The Ministry of a Poor Church: The Praxis of Justice

4. Mission Inter Pauperes: Mission Moving beyond the Pact of the Catacombs

5. Conclusion: “May God help us to be faithful”

7. The Pact of the Catacombs and the Church in Africa (Mary-Noelle Ethel Ezeh)

1. Introduction

2. Background to the Pact of the Catacombs Domitilla: the ideals of Vatican II on socio-economic life

2.1. The Common Destination of Earthly Goods

2.2. Reform of lifestyle

2.3. Change of Structures and Policies to Benefit the Poor

3. The Pact of the Catacombs Domitilla: an episcopal mea culpa, metanoia and commitment

3.1. A simple Lifestyle

3.2. Participatory/Collaborative Leadership

3.3. Creation of a New-Social Order

4. The Challenge of the Pact of Catacombs Domitilla to the Church in Africa

5. Attitude to Wealth and Lifestyle in an African context

6. Attitude to Authority and Power

7. Conclusion

8. Mission of the Church in an Indian Church of Poor People (Virginia Saldanha)

1. Start of Mission in India

2. The Positive Contribution of the Catholic Church in India

3. Institutions: challenge or boon to mission?

4. Our Faulty Understanding of Mission

5. The New Vision of Church for Mission in Asia and India

6. Challenges that Keep the Indian Church from Moving forward towards the Reign of God

6.1. To Become a Church of the poor

6.2. To Become an Inculturated Church

6.3. To Actively Participate in the Struggles of Peoples for Justice, Dignity and Equality

7. Conclusion

9. The Catacomb’s Pact is to Speak to Us Now (in China) (Paul Han)

10. Broadening the Pact. Egalitarian roots and backgrounds in Jesus’ movement (Mercedes Navarro Puerto)

1. The wisdom stream in the Hebrew bible

1.1. Lady Wisdom

1.2. The legacy of Sophia

2. Wisdom and the gospels

2.1. The core metaphor of the gospels

2.2. The wisdom dimension of Jesus transmitted by the gospels

3. The difficult equality of primitive Christianity

3.1. The women’s claims

3.2. Contrasts and socio-cultural influences

3.3. The way ahead of us

11. A pact for consecrated life. Return to the Gospel, prepare the future (José Antunes da Silva)

1. Challenges of the Pact of the Catacombs

1.1. Return to the sources

1.2. The poor: the hermeneutical key

1.3. Consecrated life with an outgoing attitude

1.4. Many faces, one heart

1.5. Cultivating dialogue

1.6. Leadership for service

2. Awakening the world

3. Preparing for the future

Contributors

Créditos

Presentation

1. Context

In 2015 the Catholic Church is celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second Vatican Council, a council that was a landmark in the two thousand years of the Church’s history. At the end of the Council, inspired by what was being done and said in the Council hall, some forty bishops from various countries of the world met in the Catacombs of Domitilla to sign what is today known asThe Pact of the Catacombs, a text and programme that sets outthe mission of the poor in the Church.

With this Pact the bishops committed themselves to walk with the poor and be not only a Church for the poor, but also of the poor, since it is the poor who embody and carry out the Gospel’s highest mission. To achieve this end the bishops decided to adopt a simple style of life, characteristic of the poor, renouncing not only the symbols of power, but all outward power, as a way of recovering, with the help of the Triune God and the Spirit of Christ, the original missionary impulse of the Church for the contemporary world (it was 1965), marked by the harsh economic struggle and general oppression of the poor.

The spirit of the Pact of the Catacombs has guided some of the best Christian initiatives of the last fifty years, not only in Latin America, where it had particular impact, but throughout the Catholic Church, so that its witness (its inspiration and its text) have become one of the most influential and important signs of twentieth-century Catholicism. This Pact remains as important today as when it was signed, and we can and must receive and promote it with more force than at the time of the Council, even though not all of us Christians (individuals and communities), have welcomed it with the same enthusiasm.

It is therefore good to use this date (its fiftieth anniversary) to celebrate it. This is what Pope Francis feels: through his words and his example of life he has once more placed the option for the poor at the centre of the Church’s life and teaching, overriding whatever vacillations may have existed on the subject. In the same spirit we may assert that, following the spirit of Vatican II and the message of Pope Francis, the Pact of the Catacombs of Domitilla can and must be an inspiration and a guide for the whole Church.

This feeling has in a special way inspired the Divine Word Missionaries, who not only are the custodians of the Catacombs of Domitilla, where this Pact was signed, but also wish to promote a Christian mission carried out from the position of the poor and with them. In this sense, without abandoning the “mission to the nations”, i.e. to peoples who are not yet Christians, we have to take up in a special, privileged way, the “mission to the poor” with Jesus himself, who came to evangelise the poor (cf. Lk 4:18-19; Mt 11:3), as this Pact emphasised.

To act on this decision, on the fiftieth anniversary of this document and of the end of Vatican II, we have brought together in this book not only the text of the Pact and the names of those who signed it, but also some important studies that help to explain it, place it in its past history, and also suggest its relevance for today and for the future. We want this Pact to continue to provide a message of encouragement for the whole Church, not only for the bishops, who were and are primarily responsible for the “mission to the poor”, but also for all Christians committed to the work of the Gospel; we are thinking particularly of women and men religious so that there can be an updating of the structures of consecrated life and its way of serving the poor from its union with Christ, as has been emphasised in this year, 2015, devoted to it.

This book seeks to make known and has adopted the gift and the task of the Pact of the Catacombs, its content and its implications for the life of the Church. That is why we wanted to study it from various points of view – its biblical and ecclesiological foundations, the option for the poor, the Church’s commitment and evangelisation in terms of today’s world, fifty years after Vatican II – to contextualise and give force to its message. We have done this with three principal aims:

1. To understand and adopt more firmly the spirit of Vatican II and the Church commitments made by the bishops in the Pact of the Catacombs;

2. To renew the commitment made by the whole Church to transform human life and build a world based on solidarity and justice, starting from the Gospel of the poor;

3. To endorse with the “fathers” of the 1965 Pact the invitation that Pope Francis keeps giving us in 2015 to be a Church of the poor that evangelises and serves human beings out of its own poverty.

The Pact of the Catacombs was intended as the specific text and commitment of a limited number of bishops (forty), who signed it in their own names, in the context of the Council, but not in the rich Vatican basilica, but in the poor catacomb of Domitilla, in a place that keeps alive the tradition of the Church of the persecuted and excluded in ancient Rome. But these bishops were representative of many other Council fathers, perhaps around 700, most notably Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro of Bologna, remembered for his commitment to the service of the poor in the Church. In this context it is also appropriate to remember the groups of “poor Christians”, many linked to the memory of Charles de Foucauld and the Little Brothers of Jesus, who did so much in the context of the Council to highlight the memory of the Christ of the poor. This memory allows us to interpret the Pact in a perspective that is not just that of bishops, but also of history and theology, open to all the areas of Christian life and mission.

2. The text

Pact of the Catacombs

(Catacombs of Domitilla, 16 November 1965)

On 16 November 1965, a few days before the end of the Council, around forty Council fathers celebrated the Eucharist in the Catacombs of Domitilla. They prayed “to be faithful to the spirit of Jesus” and at the end of the celebration they signed what they calledThe Pact of the Catacombs.The “Pact” is an invitation to their “brothers in the episcopate” to live a “life of poverty” and to be a Church “of service and poverty”, as John XXIII had wanted. The signatories - who included many Latin Americans, notably Brazilians, who were later joined by others - committed themselves to live in poverty, to reject all symbols or privileges of power, and to place the poor at the centre of their pastoral ministry.

We, bishops, gathered at the Second Vatican Council, conscious of the inadequacies of our life of poverty in terms of the Gospel, motivated by each other in an initiative in which each of us has avoided standing out or taking leadership, united with all our brothers in the episcopate, relying above all on the grace and strength of our Lord Jesus Christ, on the prayers of the faithful and priests of our respective dioceses, placing ourselves in thought and prayer before the Trinity, before the Church of Christ and before the priests and faithful of our dioceses, with humility and awareness of our weakness, but also with all the determination and all the strength that God wills to give us as his grace, make the following commitments:

1. We shall seek to live in the ordinary way of the people around us as regards accommodation, food, transport and everything that follows from this. Cf. Mt 5:3; 6:33f; 8:20.

2. We renounce forever the appearance and the reality of wealth, especially in dress (rich vestments, striking colours) and in symbols made of precious metals (these signs must certainly be evangelical). Cf. Mk 6:9; Mt 10:9f; Acts 3:6 (“No gold or silver”).

3. We shall not possess property or buildings, nor shall we have banks accounts, etc., in our own names, and if it is necessary to possess anything, we shall place it all in the name of the diocese or of social or charitable institutions. Cf. Mt 6:19-21; Lk 12:33f.

4. As far as possible, we shall entrust the financial and material management of our dioceses to a committee of laypeople who are competent and conscious of their apostolic role, in order to be less administrators and more pastors and apostles. Cf. Mt 10:8; Acts 6:1-7.

5. We reject being addressed either verbally or in writing by names and titles that express greatness and power (‘Eminence’, ‘Excellency’, ‘My Lord’…). We prefer to be called by the Gospel title of ‘Father’. Cf. Mt 20:25-28; 23:6-11; Jn 13:12-15.

6. In our behaviour and our social relations we shall avoid anything that might appear to grant privileges or priority or to show preference for the rich or powerful (for example in giving or attending banquets or having distinctions in religious services). Cf. Lk 13:12-14; 1 Cor 9:14-19.

7. Similarly we shall avoid encouraging or flattering the vanity of anyone, in repaying or asking for help, or for any other reason. We shall invite our faithful to consider their donations as a normal part of worship, the apostolate and social action. Cf. Mt 6:2-4; Lk 15:9-13; 2 Cor 12:4.

8. We shall give all that is required of our time, thought, heart, resources, etc. to the apostolic and pastoral service of people and groups that are workers and economically weak and underdeveloped, without letting this prejudice other people and groups in the diocese. We shall support the laity, religious, deacons and priests whom the Lord calls to evangelise the poor and the workers by sharing their lives and work. Cf. Lk 4:18f; Mk 6:4; Mt 11:4f; Acts 18:3f; 20:33-35; 1 Cor 4:12; 9:1-27.

9. Conscious of the demands of justice and charity, and of the relationship between the two, we shall seek to transform charitable institutions into social programmes based on charity and justice directed to all, as a humble service to the relevant public bodies. Cf. Mt 25:31-46; Lk 13:12-14; 33f.

10. We shall do everything possible to ensure that the leaders of our governments and public services adopt and put into practice the laws, structures and social institutions that are necessary for justice, equality and the harmonious and complete development of the whole human being and of all human beings and thereby for the coming of a new social order worthy of human children and children of God. Cf. Acts 2:44f; 4:32-35; 5:4; 2 Cor 8-9; 1 Tim 5:16.

11. Since the collegiality of bishops finds its fullest Gospel realisation in common service to the majorities in physical, cultural and moral poverty – two-thirds of humanity – we commit ourselves:

* to share, according to our possibilities, in the urgent programmes of the bishops of the poor nations;

* to ask jointly, in international bodies, always giving witness to the Gospel, as Pope Paul VI did at the United Nations, for the adoption of economic and cultural structures that do not produce poor nations in an increasingly rich world, but enable the poor majorities to escape from their poverty.

12. We commit ourselves to share our lives in pastoral charity with our sisters and brothers in Christ, priests, religious and laity, so that our ministry becomes a true service. Therefore

* we shall make every effort to make a “revision of life” with them;

* we shall look for collaborators so that we may be more like animators in the spirit of the Gospel than bosses on a worldly model;

* we shall seek to make ourselves present and welcoming as far as is humanly possible;

* we shall be open to all, whatever their religion. Cf. Mk 8:34f; Acts 6:1-7; 1 Tim 3:8-10.

13. When we return to our dioceses we shall inform the people of our dioceses of these resolutions, asking them to help us with their understanding, their collaboration and their prayers.

May God help us to be faithful.

3. Signatories1

There is no official list of the 39 bishops present at the celebration of mass in the Catacombs of Domitilla on 16 November 1965 when the Pact of the Catacombs was signed. They wanted to have a discreet celebration far from the press, with a few bishops (originally it was presumed that there would be only about 20) to prevent their act of simplicity and commitment being interpreted as a ‘lesson’ to the other bishops. As a result the first report of the celebration appeared in a note by Henri Fesquet in the French newspaperLe Mondeover three weeks later, as the Council ended on 8 December 1965, under the title “Un groupe d’évêques anonymes s’engage à donner le témoignage extérieur d’une vie de stricte pauvreté” (“An anonymous group of bishops commit to giving outward witness of a life of strict poverty”); cf. Henri Fesquet,Journal du Concile,Forcalquier, París 1966, pp. 1110-13). The report did not mention names, but in the papers of Mgr Charles Marie Himmer, bishop of Tournai, Belgium, who presided at the celebration in the morning and gave the homily, a list of the participants was found.

Brazil

Dom Antônio Fragoso (Crateús-Ceará)

Dom Francisco Mesquita Filho Austregésilo (Afogados da Ingazeira, Pernambuco)

Dom João Batista da Mota e Albuquerque, archbishop of Vitória, Espírito Santo

P. Luiz Gonzaga Fernandes, who was to be consecrated auxiliary bishop of Vitória

Dom Jorge Marcos de Oliveira (Santo André-São Paulo)

Dom Hélder Câmara, archbishop of Recife

Dom Henrique Golland Trindade, OFM, archbishop of Botucatu, São Paulo

Dom José Maria Pires, archbishop of Paraíba, Paraíba.

Colombia

Mgr Tulio Botero Salazar, arcbishop of Medellín

Mgr Antonio Medina Medina, auxiliary bishop of Medellín

Mgr Aníbal Muñoz Duque, bishop of Nueva Pamplona

Mgr Raúl Zambrano, bishop of Facatativá

Mgr Angelo Cuniberti, Vicar Apostolic of Florencia

Argentina

Mgr Alberto Devoto, of the diocese of Goya

Mgr Vicente Faustino Zazpe, of the diocese of Rafaela

Mgr Juan José Iriarte of Reconquista,

Mgr Enrique Angelelli, auxiliary bishop of Córdoba

Other Latin American countries

Mgr Alfredo Viola, bishop of Salto (Uruguay)

Mgr Marcelo Mendiharat, auxliary bishop of Salto (Uruguay)

Mgr Manuel Larraín, bishop of Talca (Chile)

Mgr Gregorio McGrath Marcos, bishop of Santiago de Veraguas, Panama

Mgr Leonidas Proaño, bishop of Riobamba, Ecuador

France

Mons Guy Marie Riobé, bishop of Orleans

Mons Gérard Huyghe, bishop of Arras

Mgr Adrien Gand, auxiliary bishop of Lille

Other European countries

Mgr Charles Marie Himmer, bishop of Tournai, Belgium

Mgr Rafael González Moralejo, auxiliary bishop of Valencia, Spain

Mgr Julius Angerhausen, auxiliary bishop of Essen, Germany

Mgr Luigi Bettazzi, auxiliary bishop of Bologna

Africa

Mgr Bernard Yago, archbishop of Abidjan, Ivory Coast

Mgr José Blomjous, bishop of Mwanza, Tanzania

Mgr Georges Mercier, bishop of Laghouat in the Sahara, Africa

Asia and North America

Mgr Hakim, Melchite bishop of Nazareth

Mgr Haddad, Melchite bishop, auxiliary bishop of Beirut, Lebanon

Mgr Gérard Marie Coderre, bishop of Saint Jean de Québec, Canada

Mgr Charles Joseph van Melckebeke, Belgian-born, bishop of Ningxia, China

Translated by Francis McDonagh

1Source: Rev. José Óscar BEOZZO, 29.06.2009:http://nucleodememoria.vrac.puc-rio.br/site/dhc/textos/beozzocatacumbas.pdf.

Introduction

HEINZ KULÜKE

Some years ago I got an invitation to give a talk to a group of missionary sisters in Cebu, in the Philippines, about our social and pastoral work. This invitation I kindly declined. Instead I invited the sisters to come and visit our project areas, to meet and learn from the poor we were journeying with at that time and thus to simply see for themselves. We began with a visit to the garbage dumping sites and then in later months met with people in the streets and red light districts.

Initially the extremely poor living and working conditions, the dirt and the smell, the numerous women and children suffering that touched the sisters’ hearts. But right from the beginning the sisters also experienced the honest friendliness, the trust, sympathy, simplicity, hospitality, care, warm welcome and basic joy of the poor so generously shared with their visitors.

The first encounter with the people in the garbage pit left a lasting impression on the sisters, something a talk never could have achieved. The sisters started coming back every weekend. More and more sisters came. Also the older sisters joined “the new outreach” as they called their Saturday afternoon activity. They had heard from the younger sisters and wanted to see for themselves. Not much time passed and the sisters brought friends along. The sisters’ friends too wanted to see for themselves. The sisters discovered a place where they could not only give and share but also a place where they could learn. Till today the sisters are with those at the margins.

The “unplanned effects” of that episode are numerous: The sisters’ number of friends has increased ... The poor have become an essential part of the sisters’ daily conversations, their concerns, their planning, their formation programs, their faith, their liturgy and their prayers. Furthermore, the poor have brought us – Divine Word Missionaries, Missionaries Servant Sisters of the Holy Spirit, and lay mission partners – together anew in a life giving and working relationship. Now we have something to talk about when we meet, not merely about ourselves. We identify problems together, look for solutions together, plan, implement and evaluate our projects together. The good example of the sisters has inspired and still inspires many of us and our lay mission partners. The encounter with those at the margins has become a genuine blessing. Where God has found his home religious also can find a new home and new meaning.

I recall this experience as we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Pact of the Catacombs, a commitment signed by a group of bishops to be closer to the poor. Several initiatives have been organized to celebrate the Pact of the Catacombs and among them the publication of this book. This occurs in the context of two important events in the Church: the 50th anniversary of the closing of Council Vatican II, and the celebrating of the Year of Consecrated Life.

The Vatican II was a milestone in the recent history of the Catholic Church. The Council offered orientation and guidelines to renew the Church; to make it closer to the lives of the people and attentive to the challenges of the world; it proposed a renovation of Christian life inspired by the Gospel. Moved by what was going on and what was said during the Council, already towards its end 40 bishops from all over the world signed a pact in the Catacombs of Domitilla known as the Pact of the Catacombs. With this gesture, the bishops promised to journey with the poor and to be a poor Church that serves the poor by living a simple life style and withdrawing symbols of power.

In convoking the Year of Consecrated Life, Pope Francis wanted to propose again to the Church as a whole the beauty and value of this special form of discipleship of Christ. He renewed the call to wake up the world and to illuminate it with our prophetic and countercultural witness. In the letter written for this occasion, Pope Francis writes: “I am counting on you ‘to wake up the world’, since the distinctive sign of consecrated life is prophecy. [...] Prophets know God and they know the men and women who are their brothers and sisters. They are able to discern and denounce the evil of sin and injustice. Because they are free, they are beholden to no one but God, and they have no interest other than God. Prophets tend to be on the side of the poor and the powerless, for they know that God himself is on their side”1. Celebrating the Pact of the Catacombs is a way to renew the commitment of religious women and men to the prophetic dimension of their mission and vocation. In line with the spirit of Vatican II this can be very inspiring for the whole Church today.

The Pact of the Catacombs brings us in contact with the essentials of our faith, the simplicity of the Gospel. It is true that it remained unknown to the wider Church for many years, as only a small minority of Christians kept its memory alive. Fortunately, recently it has been made known. The Pact is like a hidden gem that sees the light of day. But, unlike the treasures of archeological research, the nature of the Pact is not to be preserved in a museum to be admired by lovers of ancient artifacts. As I read the Pact of the Catacombs some questions come to my mind: What are we going to do with this rediscovered treasure? Bury it again or, on the contrary, make it profitable? (cf. Lk 19,11-26). How relevant can the Pact be for the future, a pact that has been in existence for some 50 years already, a pact that probably did not have the impact that it wanted and envisioned to have? Have the times changed for a bigger impact of the pact?

Besides making the Pact known to the wider public, the publication of this book is a contribution to revive the spirit of Vatican II, renewing the commitment of the whole Church for the transformation of the world, reinforcing the invitation of Pope Francis for a poor Church that serves the poor, and contextualizing the Pact’s message for the Church of today. As we celebrate the 50 years of the Pact, we need to make it flourish into new projects, new avenues of life and brotherhood, in lives committed to serving the poor, in policies that bring about justice and peace. I think that we could also develop what was not explicitly stated in the Pact when it was signed, due to its historical context, but what can easily be foreseen, for example, the role of women in the Church and in society, the harmony with creation, environmental protection, prophecy as an alternative attitude, critique of consumerism, the fight against corruption etc.

The Catacombs of Domitilla belong to the Holy See but, in 2009, they were entrusted to the care of the Society of the Divine Word. The fact that we are in charge of running these particular catacombs has become for us an opportunity to strengthen our commitment as missionaries at the service of the Kingdom of God. The vision and the ideas highlighted in the Pact are very much in line with the vision and the mission of our Society. Following our last General Chapter (2012) we adopted the motto: missio inter gentes – putting the last first. Thousands of pilgrims and tourists visit this sacred place every year. Being the caretakers of the Catacombs of Domitilla, offers an opportunity to make known the Pact and to commit ourselves anew to the missionary vision of our Society.

Pope Francis reminds us in Evangelii Gaudium that both Christian preaching and life “are meant to have an impact on society” (EG 180). Furthermore, every community “is called to be an instrument of God for the liberation and promotion of the poor, and for enabling them to be fully a part of society. This demands that we be docile and attentive to the cry of the poor and to come to their aid” (EG 187). Pope Francis also writes that he wants “a Church which is poor and for the poor” (EG 198). The bishops who 50 years ago signed the Pact of the Catacombs had the same dream and thought for it. Let us be inspired by their commitment and their prophetic words, and let us try to give up our lives at the service of those who are more vulnerable and marginalized.

1 Pope FRANCIS, To All Consecrated People on the Occasion of the Year of Consecrated Life (2014).

1

Church of the poor

LUIGI BETTAZZI

1. The Church of the poor at the Council: the beginnings

“The Church is presenting itself as it is and wants to be, as the Church of all and particularly the Church of the poor.” The remark, uttered by John XXIII on 11 September 1962 (a month before the opening of the Second Vatican Council), went unnoticed by public opinion, but had been illustrated by that same pope in the light of the great encyclical Mater et Magistra, as a “rigorous affirmation, the duty of every human being, the pressing duty of every Christian...to measure superfluity by the standard of the needs of others and to take great care that created things are placed at the disposal of all. This is called spreading the sense of society and community that is inherent in genuine Christianity.” This remark about the expectations of the world, of the most needy, of the underdeveloped nations, was guidance for the first session of the Council.

This appeal has already been present in the Greeting to the bishops of the world, and made all the more urgent by the experience of the bishops from the regions of the world that were poorest and most in need of development: “Gathered here from every nation under heaven, we carry in our hearts the concerns of all the peoples entrusted to us, the sorrows of soul and body, the pains the desires, the hopes. Our thoughts are constantly on all the anxieties that afflict people today, but in the first place our concern is directed to the lowliest, the poorest, the weakest. Following the example of Christ, we feel pity for the crowd that suffers hunger, poverty, ignorance, and we think constantly of those who are deprived of the support they need and have not attained a standard of living worthy of human beings... Truly, ‘How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?’ (1 Jn 3.17).”

The question of poverty was also present in the interventions as early as the discussion of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. In this way we can see how the discussion of poverty, the ideal and the call for the Church of the poor gradually connected with their deep theological and biblical roots. Reflection on the fact that Christ chose to be poor, and proclaimed the spirit of poverty as the first of the beatitudes, provided an argument for calling for simplicity in the Church’s worship and to look beyond an excessive concern for pomp that in other times might have seemed justified as seeking to give dignity and honour to God. In this spirit the Chilean bishop Manuel Larraín stressed that, since the liturgy is “the memorial of the paschal mystery, the summit of the life of Jesus”, it must be “completely marked by a clear and genuine poverty, but with beauty... The mystical body of Christ must really be the Church of the poor, not only in desire but also in fact, not only in preaching but also in action, in the way its ministers behave and live: this is the mission of pastors. It is not only the liturgical ornaments and vestments that must better express the Gospel, but all the dress and behaviour of the Church’s ministers, following the beautiful poverty of Jesus Christ.”

But it was in the discussion of the schema on the Church that the theme of poverty, of the Church of the poor, of the simplicity of the Church as faithfulness to its nature and an effective means of evangelising the world, was presented especially by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, archbishop of Milan, and Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro, archbishop of Bologna (who relied on the advice of his personal theologian, Fr Giuseppe Dossetti). The most significant intervention came from Cardinal Lercaro, because, while stressing the intimate mystery of the Church as the “great sacrament of Christ”, of the Word of God who reveals himself, dwells, lives and works among human beings, he rephrased Pope John XXIII’s definition by saying: “The mystery of Christ in the Church is always, but especially today, the mystery of Christ in the poor, because the Church is indeed the Church of all, but especially the Church of the poor.”

In stressing this call and regretting that it was not adequately represented in the various schemata, Cardinal Lercaro emphasised that the essential and primordial revelation of the mystery of Christ was an aspect foretold by the prophets as an authentic sign of the messianic consecration of Jesus of Nazareth, an aspect that became clear in the birth, infancy, hidden life and public ministry of Jesus, an aspect that is the basic law of the kingdom of God, which leaves its mark on every outpouring of grace and on the life of the Church, from the apostolic community to the periods of most intense internal renewal and fruitful outward expansion and will in the end be ratified by the Father with reward or punishment at the glorious coming of the Son of God at the end of time.

Cardinal Lercaro subsequently developed this biblical theme in a number of talks, also given publicly to groups of bishops, stressing the Gospel beatitude reserved for the poor. He meant this concept first of all in a religious sense, the moral conditions, that is, of a person lacking earthly goods. Comparing it with the other beatitudes directed at children and sinners, he remarked: “God chooses to grant his gifts to those whom human beings judge least worthy. The lesson of this teaching is not directly moral, but theological: God’s preferences are for those creatures, who from a human point of view, are most deprived precisely because entry to the kingdom of heaven is not presented as a reward. It is rather a teaching on the absolutely gratuitous mercy of God, who chooses to grant salvation to those, who conscious of being unworthy of it, will receive it as a gift of his mercy. We are not talking about moral dispositions the poor should have, but about the fact that Christ was sent to console them.”

When Cardinal Lercaro set out in detail the theological basis of the Church of the poor, he also highlighted its particular relevance: “We are in fact in a period in which, in comparison with others, the poor seem to be less evangelised, and their minds seem distant from and uninvolved in any contact with the mystery of Christ in the Church. But it is a period in which the human spirit is querying and examining with anguished, even dramatic, questioning the mystery of poverty and the conditions of the poor, of every individual in poverty, but also of the peoples that live in destitution and nevertheless are becoming aware for the first time of their rights. It is a period in which the poverty of the many (two-thirds of the human race) is outraged by the immense wealth of a minority, in which poverty creates a daily increasing horror and the person of flesh feels the thirst for wealth.”

By stressing in this way the theological importance and the relevance, including for ecumenical relations, of the question of the poor, Cardinal Lercaro was asking, not so much that the issue of the evangelisation of the poor be added as an additional topic for the Council agenda, but rather that it should illuminate the treatment of the various topics the Council itself would be considering. In other words, he was asking for the Gospel teaching on Christ’s holy poverty should be made explicit, for the special dignity of the poor as privileged members of the Church to be emphasised, for prominence to be given to the ontological connection between the presence of Christ in the poor and the other two deeper aspects of the mystery of Christ in the Church (the presence of Christ in the action of the Eucharist and in the hierarchy). This was matched by his proposal that when the schemata on the reform of Church institutions were discussed, prominence should be given to the historical connection between the loyal and active recognition of the special dignity of the poor in the kingdom of God and in the Church and our ability to identify the obstacles faced by these institutions, their possibilities and ways of adapting them. He also offered a variety of specific examples of the approaches that could be taken in the reform decrees with wisdom and maturity, but also without compromise or timidity; these included limits on the use of material goods, a new style for office-holders in the hierarchy, faithfulness to holy poverty on a community level as well, in the case of religious congregations, a change of behaviour in economic matters, including the abandonment of some institutions from the past that no longer served any purpose and were obstacle to a free and generous exercise of the apostolate.

If I have given such a long account of Cardinal Lercaro’s intervention, I have done so, not only because of its unique significance and completeness, but also and especially because it was the sparkling spring that made possible the fruitful rethinking that then took place in the Council and spread out through the whole Church even after the Council. Moreover the intervention was only the successful conclusion of a long period of work carried out in secret during the same first session and promoted by a number of bishops particularly sensitive to this problem; they met in the Belgian College and therefore became known as “the Belgian College study group”. Cardinal Lercaro’s intervention summarised the ideas and concerns of a great many pastors who were particularly sensitive to this urgent problem facing the Church in its evangelisation of the world. One example is the way Mgr Alfred Ancel, auxiliary bishop of Lyon, one of the most authoritative interpreters of this sensitivity, described situations that he had no hesitation in calling “signs of the times”: the poor, he argued had not really been evangelised, or only minimally, the hungry countries were the pagan countries, and in the Christian countries one only needed to look at the situation of the mass of workers, and among them manual workers. “Today’s world, he bitterly commented, is a machine for producing poverty.” The poor throughout the world, he said, could no longer endure their situation and were looking, in one way or another, for development (as social groups) and independence (as colonised nations). In many Christian countries, he added, the poor see the Church as a stranger or even an enemy, a rich and powerful body allied with the rich and powerful. But in the Church there is a growing turning towards poverty and the service of the poor, in the testimony of increasing numbers of lives, whether of individuals or communities, not only of religious, but also of priests and lay people, including married couples. “Personally – and I know that many people share this view –, the auxiliary bishop of Lyon remarked, ‘I am deeply convinced that we have become part of an irresistible and irreversible movement. In the Church of God the Holy Spirit has inaugurated a new age that will be marked by a profound renewal in accordance with the Gospel. This renewal will be at once doctrinal and pastoral and will take place under the sign of poverty, of service to the poor and the evangelisation of the poor.”

After carefully examining the perplexities and criticisms such a movement could provoke, Mgr Ancel indicated the ways in which it could be developed: theology would have to be renewed so that it could achieve a deeper contemplation of Christ as a poor person, to give a complete doctrinal account of the poor, images of Christ and our sisters and brothers, and to present evangelical poverty as both a human and a spiritual value. On a practical level, he argued that it was essential to have a poor person’s soul, filled with humility, tenderness and apostolic zeal towards our poorer sisters and brothers; we also needed to dedicate ourselves to the service of the poor, individually and collectively through institutional action, combining competence and organisation with a genuine Gospel spirit.

Finally, Mgr Ancel offered three principles for the evangelisation of the poor – presence, hope and universal love – and three principles for the evangelisation of the rich – love, renunciation of wealth and evangelical poverty, and acting with the spirit of poor people. He also named three attitudes that the Church needed to adopt: a renunciation of any triumphalism (the Church should present itself to the world not as dominant, but as a servant), independence from any political power or the various social strata, and a commitment to be the living image of Christ. Of course, he said, it would be necessary to study more deeply how the Church could bear authentic witness in the contemporary world, especially in the light of the Council’s decisions and those that would follow by bishops conferences and individual bishops. It would be necessary prepare for this change out attitude among clergy and the faithful through individual and collective education.

2. The Church of the poor at the Council: the developments

During the second session of the Council there were many interventions of Council Fathers that referred to this spirit, to the prospect of the Church of the poor, and there were many meetings of the Belgian College group and other similar groups, all designed to take further such an important idea that had emerged from the Council.