13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

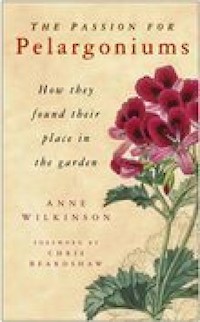

Quick and reliable to grow for summer colour, and well marketed, most gardeners will have at least one pelargonium in their garden or conservatory, without realising either the number or variety of species available, nor the plant's extraordinary history.The Passion for Pelargoniums reveals the fascinating and dramatic tales of those who have been involved in finding, classifying, collecting and breeding the plants. It explodes the myth that all modern versions of the plant are descended from the oldest known variety - the seventeenth-century drab-coloured P. triste, literally translated as the sad pelargonium, and reveals that 2,000 hybrids have been developed from less than a dozen plants originally imported from the East. From the contribution of L'Heritier, whom Sir Joseph Banks named 'an impudent Frenchman', to collectors like Masson and the Marquess of Blandford (known for his 'elegant emporium'), competing nurserymen determined to make both fortunes and reputations, and the burgeoning Victorian varieties as growers searched for the holy grail of the scarlet geranium, the book recounts the plant's extraordinary history. Today, while traditional white ones, doubles, 'nosegays' and 'rosebuds' still flourish, the 'lemon-scented geranium' is only one of a number of scented varieties, while pelargoniums can have flowers of pink, red, purple, yellow or black. This is the story of how the passion felt by gardeners for their plants stirred them to bitter rivalry and criminal obsession, scandal, fraud, and fast dealing, and saw polite society being rather less than polite.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Ähnliche

THE PASSION FOR

Pelargoniums

THE PASSION FOR

Pelargoniums

How they found theirplace in the garden

ANNEWILKINSON

FOREWORD BYCHRISBEARDSHAW

First published in 2007

The History PressThe Mill, Brimscombe PortStroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved© Anne Wilkinson, 2007, 2013

The right of Anne Wilkinson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 96061

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Acknowledgements

A Pelargonium Chronology

Introduction

1.

Splendid Curiosities

2.

Delights for Aristocrats

3.

The Impudent Frenchman

4.

‘The First Practical Botanist in Europe’

5.

The Quest for the Perfect Pelargonium

6.

The Age of Bedding

7.

Flights of Fancy

8.

Flowers for the Million

9.

The Final Flowering of the Nineteenth Century

10.

Demise and Renaissance

11.

Regaining the Treasures of the Past

Appendix 1:

Botanical Classification of Pelargonium Species

Appendix 2:

Horticultural Classification and Glossary

Appendix 3:

List of Suppliers and Organisations

Notes and Sources

Bibliography

To Isabelle and Florence

List of Illustrations

Colour Plates

1.

Mrs Delany’s ‘paper mosaic’ of

P. fulgidum

2.

P. caffrum

3.

P. oblongatum

4.

P. triste

5.

Bedding at Bowood House

6.

P.

×

rubescens,

the Countess of Liverpool’s Storksbill

7.

P.

×

daveyanum,

Davey’s Storksbill

8.

P.

×

involucratum,

the Large-bracted Storksbill

9.

Beaton’s ‘Indian Yellow’

10.

Coloured-leaved Zonals

11.

Young Lady in a Conservatory

12.

‘Duchess of Sutherland’ Nosegay

13.

French or ‘Spotted’ pelargoniums

14.

Zonal pelargonium and hybrids

15.

Fancy, Show and Decorative pelargoniums

16.

Catalogue of Caledonian Nurseries

Black and white illustrations

1.

Zonal pelargonium

2.

Geranium and pelargonium flowers compared

3.

Seedpod from

Pelargonium capitatum

4.

John Tradescant’s house in Lambeth

5.

William Bentinck, Earl of Portland

6.

The Duchess of Portland

7.

Dr John Fothergill

8.

Excerpt from Kew record book

9.

William Curtis

10.

P.

×

striatum

11.

Sir Richard Colt Hoare

12.

‘Large-flowered’ pelargonium

13.

Florists’ flower diagram

14.

Captain Thurtell’s ‘Pluto’

15.

Edward Beck

16.

Beck’s ‘Harlequin’

17.

George W. Hoyle

18.

French or ‘Spotted’ pelargonium, ‘La Belle Alliance’

19.

Donald Beaton

20.

Ciconium crenatum

21.

Francis Rodney Kinghorn

22.

Diagram for a ‘panel garden’

23.

Design for a flower bed

24.

Design for Liverpool Botanic Garden

25.

The ‘geranium pyramid’ at Stoke Newington

26.

The parterre at Eythrope

27.

Peter Grieve

28.

Leaf of ‘Sophia Cusack’

29.

Leaf of ‘Princess of Wales’

30.

Diagram showing Peter Grieve’s pelargoniums

31.

Leaf of ‘Crimson Nosegay’

32.

Henry Cannell

33.

Ivy-leaved pelargoniums in hanging basket

34.

Victor Lemoine

35.

Wilmore’s Surprise

36.

J.R. Pearson’s Chilwell Nursery

37.

John Royston Pearson

38.

‘Rienzi’ – florists’ Zonal pelargonium

39.

Pelargonium Society certificate

40.

Charles Turner

41.

Victorian plant seller

42.

Victorian paper collage

43.

Pelargonium album,

an early Regal pelargonium

44.

William Bull

45.

Bull’s catalogue showing ‘Beauty of Oxton’

46.

Bruant’s pelargoniums ‘de grand bois’

47.

Gardener with a potted pelargonium

48.

Advertisement for Zonate pelargoniums

49.

Cannell’s Floral Guide

for 1910

50.

Bedding display, ‘basket of flowers’

51.

Inside an amateur’s greenhouse, 1904

52.

Victorian pressed pelargoniums

53.

Poster for Liverpool International Garden Festival

Plant profiles

P. triste

P. cucullatum

P. zonale

P. peltatum

P. capitatum

P. inquinans

P. gibbosum

P. papilionaceum

P. odoratissimum

P. fulgidum

P. betulinum

P. echinatum

P. tricolor

P. panduriforme

P. tomentosum

P.

×

ardens

P.

×

ignescens

P.

×

fragrans

‘Rollisson’s Unique’

‘Mrs Pollock’

‘Mrs Quilter’

‘L’Elegante’

‘New Life’

‘Freak of Nature’

‘A Happy Thought’

‘Apple Blossom Rosebud’

Regal ‘Geoffrey Horseman’

‘Red Black Vesuvius’

‘Madame Salleron’

‘Scarlet Unique’

‘Catford Belle’

‘Patricia Andrea’

Stellar ‘Arctic Star’

‘Deacon Lilac Mist’‘Rouletta’

‘Reticulatum’

‘Sparkle’

‘Variegated Lady Plymouth’

‘Lady Scarborough’

‘Clorinda’

Foreword

If one were to write a character profile of a fantasy plant, a genus that exhibited a palette of favourable and admirable attributes, how might it read? For me it would be essential that the plant had a history, a convoluted and often mysterious past that demonstrated a strong heritage, a blood line of diverse personalities resulting in offspring with gravitas. Apart from the historical facts there is folklore, shrouded in mysterious whispers spoken by learned tongue, telling tales of adventure, magic, medicine and myth. It almost goes without saying that this plant would require an unrivalled beauty, a delicacy of form, diversity of structure and a chameleon-like ability to flush with a million tints. Such an extraordinary palette would facilitate the blending and weaving of the blooms through timeless designs and countless generations. And while presenting a truly exotic face this plant would possess an appetite and enthusiasm for life and an amiability of spirit that offers a hand to novice and expert alike.

This is my recipe for a fine plant, one that touches generations of gardeners and whose character permeates social and cultural divides. However, far from being a theoretical flight of fancy, this is a perfect description of the pelargonium, whose charm and poise I first encountered as a young boy helping my grandfather to pinch out his crop. It is, therefore, entirely appropriate that this extraordinary genus should be celebrated in a book.

Chris Beardshaw

Spring 2007

Acknowledgements

This book evolved over fifteen years or more, during which time my own pelargonium collection was built up and lost three times during house moves. The reading and research continued, however, and the information came from many sources. I could not have written the book without the painstaking work of Richard Clifton of The Geraniaceae Group, whose Checklists, Notes and Commentaries were essential for reference, and I very much appreciate his help and encouragement. I was inspired to start the book by Penelope Dawson-Brown who, like Richard Soar, whom I met much later, made me realise how little I knew about Robert Sweet and Richard Colt Hoare, early ‘pelargonistes’ whose legacy is still with us today. I thank them both for their encouragement and interest. I also thank Jaqueline Mitchell and all at Sutton Publishing who had faith in the subject matter.

Most of my research took place in the RHS Lindley Library, old and new, and the expert advice from Brent Elliott and all the staff never ceased to amaze me. I also had considerable help from The Museum of Garden History, whose curator, Philip Norman, and volunteers spent more time than I deserved hunting out material. I also thank the following libraries and archives who provided extra information or pictures: Hackney Archives, British Library, British Museum, Southend Museum, Hounslow Library, Natural History Museum, Bridgeman Art Library, The Harley Gallery, The National Trust, Dickens House Museum, Guildhall Library, The Curtis Museum and Kew Herbarium.

Special thanks also go to those who helped me find plants, particularly Jack Gaines and Jane Partridge at Southend Parks Nursery, who were generous with their time and, I think, genuinely surprised that anyone should want to see their plants. They hardly knew what little gems they possessed! I thank the Stourhead gardeners and Charles Stobo of the Chelsea Physic Garden for showing me their collections, and the Vernon Geranium Nursery, Bill Pottinger, The Geraniaceae Group, Amateur Gardening and the British Pelargonium and Geranium Society for allowing me to use their pictures. I especially thank Jean-Patrick Elmes for helping me with the technicalities of photography, for the use of his pictures and for replacing plants I lost from my first collection. It’s true what they say: the best way to keep a plant is to give it away.

Finally, I would not have succeeded without the support of my daughters, Isabelle and Florence, to whom I dedicate the work.

A Pelargonium Chronology

1621–35

The ‘night-scented Indian geranium’ known in Europe and described by Thomas Johnson when he sees it in Tradescant’s Lambeth garden; first illustrated by Jacques Cornut in

Canadensium Plantarum.

1672

Paul Hermann sends

P. cucullatum

specimens from the Cape of Good Hope to Holland.

1690

P. Zonale

depicted in J. Moninckx’s

Hortus Botanicus Amsterdanensis. P. cucullatum

and

capitatum

in the garden of William and Mary in England, believed to have been brought from Holland by William Bentinck.

1700

Adriaan van der Stael sends seeds of a P.

peltatum

from the Cape to Holland.

1713

P. inquinans

included in list of plants in Bishop Compton’s Fulham garden.

1732

John Jacob Dillenius suggests the name ‘pelargonium’ (storksbill) for the seven ‘African geraniums’ in

Hortus Elthamensis

, and includes

P. fulgidum

.

1773–7

Francis Masson collects fifty different pelargoniums at the Cape.

1780

P. fothergillii

recorded as having been hybridised at Upton, Essex.

1787–1801

William Curtis depicts eighteen pelargoniums, inconsistently calling them pelargoniums, geraniums or cranesbills, but using the Linnean system, in his

Botanical Magazine.

c. 1789–92

Charles-Louis L’Heritier de Brutelle depicts forty-four pelargoniums, named as such, in

Compendium Geranologia,

establishing twenty-one species, and further figures are used in Aiton’s

Hortus Kewensis.

1797–1814

Henry Andrews’s

Botanist’s Repository

includes about sixty figures and descriptions of pelargoniums, but still names them geraniums.

1800

Carl Ludwig Willdenow divides geraniums and pelargoniums in

Species Plantarum.

1805–29

Henry Andrews’s

Geranium

monograph, depicting 194 plants, still called geraniums.

c

. 1818

Richard Colt Hoare breeds

P

. ×

ignescens

at Stourhead.

1820–30

Sweet’s

Geraniaceae

describes and depicts 500 varieties, but divides them into ten new genera.

1820s

Colvill’s nursery in Chelsea contains 400–500 varieties of pelargonium. Collections of Colt Hoare and Jenkinson contain most of the known species and are producing early hybrids.

1841

Gardeners’ Chronicle

lists criteria for the pelargonium as a florists’ flower, based mainly on hybrids of

cucullatum

and

fulgidum.

1842

‘General Tom Thumb’ is thought to be the best bedding pelargonium of its day.

1844

‘Golden Chain’ is one of the earliest variegated pelargoniums used for bedding.

1847

Edward Beck publishes his

Treatise

on the pelargonium and improves the quality of seedling pelargoniums.

1857

‘Stella’ is described as best Nosegay pelargonium.

1860–1

Chiswick trial for best pelargoniums, instigating the mystery of the origins of Uniques.

1862

John Wills hybridises Ivy-leaveds and Zonals to produce

Willsii rosea.

1863

Peter Grieve starts to produce coloured-leaved Zonal pelargoniums.

1864

Victor Lemoine produces first double Zonals.

1866

Gardeners’ Chronicle

classifies pelargoniums into twelve classes. L’Elegante, variegated Ivy-leaved, is exhibited in Birmingham.

1868

Henderson’s sell Lilliputian varieties from Saxony.

1869

Pelargonium Congress in London.

1870s

Rosebud/Noisette varieties are developed.

1874

Pelargonium Society established; florists’ Zonal recognised as a class.Bruant’s plants of ‘grand bois’ developed in France.

1877

König Albert, first double-flowered Ivy-leaved. New Life – striped sport from Vesuvius. ‘Decorative’ pelargoniums first described as Regals.

1878

‘Fringed’ or ‘frilled’ petalled flowers appear.

1884

Le Nain Blanc (Mme Salleron) sold by Bruant.

1889

Black Vesuvius – first ‘black-leaved’ plant.

1890s

Paul Crampel produced by Victor Lemoine.

1896

H. Dauthenay describes and classifies Zonal pelargoniums in

Les Geraniums.

1898

Bird’s Egg varieties in Cannell’s catalogue.

1899

Fire Dragon first cactus-flowered pelargonium.

1908

Fiat strain developed from Bruant’s ‘grand bois’ plants.

1930s

Arthur Langley-Smith develops what become known as Angel pelargoniums, using P.

crispum

and Regals.

1942

Behringer produces Irenes in USA.

1951–3

Zonal pelargoniums repopularised as bedding plants for the Festival of Britain and the Coronation, with particular emphasis on Gustav Emich.

1951

John E. Cross,

The Book of the Geranium

. British Geranium Society founded; later becomes British Pelargonium and Geranium Society.

1957

The Crocodile, first commercially produced meshleaved pelargonium.

1958

Derek Clifford’s

Pelargoniums, including the Popular Geranium

.

1960s

Francis Hartsook produces ‘modern’ Uniques from Uniques and Regals.

1964

‘Formosum’ or fingered-flowered pelargoniums produced in USA.

1966

Tulip-flowered pelargoniums produced in USA. Ted Both’s ‘Staphs’ produced, later called Stellar pelargoniums.

1967

‘Carefree’ F1 hybrids produced in USA.

1970

British and European Geranium Society formed. S.T. Stringer’s Deacon strain of pelargoniums shown at Chelsea.

1977–88

J.J.A. van der Valt’s

Pelargoniums of Southern Africa

in three volumes provides a comprehensive guide to species of Southern Africa.

1981

Geraniaceae Group formed to further information on species and early hybrids. They start to produce

Pelargonium Species Checklist

,

Decadic Cultivars

and

Commentaries

on Sweet, Andrews and L’Heritier.

1988

National Collection of Pelargoniums started by Hazel Key at Fibrex Nurseries.

1994

Peter Abbott,

Guide to Scented Geraniaceae.

1996

Diana Miller,

Pelargoniums.

2000

Hazel Key,

1001 Pelargoniums.

Introduction

This book is a celebration of pelargoniums, and the people who loved them. Passion is not too strong a word. Through three and a half centuries pelargonium growers have been driven by an obsession for this brightly coloured plant, brought from the warmth and sunshine of the southern hemisphere to the dull damp climate of northern Europe.

Little could the aristocratic enthusiasts of the eighteenth century or the commercial nurserymen of the nineteenth imagine how this interesting, but sometimes wayward, plant would become the mainstay of our summer gardens, and so apparently ordinary and mass produced that it is despised by many gardeners as just too dull to bother with. Or perhaps they could. There must have been something that drove them on to constantly hybridise the plants until they found that elusive colour or special markings that became the successive holy grails of the pelargonium world.

Modern gardeners who are tempted to reject the pelargonium as too much of a cliché and too ‘municipalised’ to put into their own gardens should pause for a moment and consider its ancestors or its cousins. The richness of the genus will surprise and delight them, and then they too will be captivated by its charm and versatility. This book explains how the garish, stiff, compact plants of today were in effect manufactured from the pliable, pungent, beautiful, vivid, delicate species discovered centuries ago by pioneer plant collectors and travellers, and adopted by marquesses and earls, medical men and ladies of leisure, humble gardeners and painstaking horticulturalists.

The joy of discovering the real pelargonium is that it is not too late to rescue it from extinction. Although many of the hybrids are lost, the species are very much alive and well, and there is nothing to stop anyone trying to re-create the old hybrids and bring back the glories of the past.

Whether you call it a geranium or a pelargonium, you will know the plant. It is grown in the majority of cultivated gardens in Britain and Europe, and many in the United States, New Zealand and Australia. It is predominantly bright red, but also appears in pinks, purples and white. In fact it is so common that most people never give it a second thought. It is picked up from the garden centre at the beginning of the summer, used to adorn the pots and window boxes on the patio, and seen laid out in rows in every public park and garden. But why? Perhaps the answer is obvious: it is colourful, easy to grow, easily available, and stands up to a considerable amount of neglect. The more expert gardeners would also say that it comes in infinite variety, is easy to propagate and even to hybridise. This is a clue to its success: throughout history it has been a hybridiser’s dream, and it can be commercially produced on a massive scale with few problems, so it is eminently marketable. It is also popular among flower show exhibitors, who love to create and try out new varieties. However, even experts often struggle to explain the history of the plant or have much knowledge of the old sorts that our ancestors once grew. Most people have no idea what an impact it had on gardeners in the nineteenth century.

First, an explanation of the name. Although most gardeners know perfectly well the difference between the so-called ‘hardy geranium’ and the ‘Zonal or bedding geranium’, they often seem reluctant to call the plants by their proper names. This is probably because writers and nurseries continue to use the wrong name, probably in the belief that if they call the ‘Zonal’ or bedding plants pelargoniums, people will be confused and not buy them. Why they should think so is difficult to understand. The names of plants are often changed and people accept the changes without much complaint. Could it be that because the pelargonium is so well known and so popular it has almost become an institution, and therefore it is thought that the whole fabric of the gardening establishment would collapse if it is challenged? Surely it cannot be that important! Some people believe that names do not matter; yet few serious gardeners would dispute the fact that using botanical names instead of common names is more accurate and informative, and should be encouraged. There is absolutely no need ever to call a pelargonium a geranium: they are distinct plants, separately named over 200 years ago. Unfortunately, however, many writers did not accept the difference, and throughout the nineteenth century certain groups of pelargoniums were still referred to as geraniums. But in the twenty-first century we have grown used to calling ‘horseless carriages’ cars or automobiles, we generally call the ‘wireless’ the radio, and we have ceased to wonder how aeroplanes stay in the air. There is really nothing difficult or confusing about calling a pelargonium by its proper name.

1. A Victorian Zonal or bedding pelargonium, generally thought of as typical of modern plants. (Shirley Hibberd, Familiar Garden Flowers, c. 1880/Author’s Collection)

The confusion came about in this way. When the pelargonium, a tender plant native to southern Africa,1 was first seen in Europe, it was thought by the herbalists of the time to be a type of cranesbill, or geranium, a familiar hardy plant native to northern Europe. In the seventeenth century botany was in its infancy and plants were generally described by likening them to another plant that had already been named. The botanists or herbalists of the time little imagined how many more plants of the same type were to appear in Europe in the following century and so at first they saw no need to invent a new category to put them in. Even when the name pelargonium had been introduced and was widely used by some botanists and gardeners, others were slow to accept it. By the nineteenth century certain types of pelargoniums were being hybridised, but others were not, so gardeners and writers felt it was convenient to use the name pelargonium for the specialised group and geranium for the others. At the time the true geranium was only seen as a wild flower of the hedgerows and barely considered a garden plant at all, so the term ‘hardy geranium’ was never used. Presumably, as ‘hardy’ geraniums were never red and the bedding pelargonium usually was, the term ‘scarlet geranium’ conveniently distinguished the two. Since those days, however, geraniums have been hybridised into popular herbaceous perennials, and should be given back their true name with no qualification.

2. Geranium and pelargonium flowers compared. The geranium (left) has five identical petals, whereas the pelargonium’s top two petals are often strikingly different, or more marked or feathered. (Author’s Collection)

Geraniums and pelargoniums are easily distinguishable from each other, even by the layman. The geranium’s five-petalled flowers are symmetrical and appear in many shades of blue, purple and pink, as well as white. They are never red or yellow, however, and are barely, if ever, scented. They can withstand temperatures below freezing and so thrive in northern gardens throughout the year. Pelargoniums, on the other hand, are not frost hardy. They are also five-petalled, but the top two petals are different from the lower three, sometimes quite strikingly, sometimes not. Even the pelargoniums that seem at first sight to have five identical petals, on closer inspection show darker markings on the top two. This distinction in petals is not the botanical way of identifying the plants, but serves well in most cases for ordinary gardeners trying to learn the difference. The pelargonium flower colours range from bright red to shades of magenta and purple, lilac, pink, white, even black and yellow, but never blue. The foliage can be green, variegated with white or cream, or can have a distinctive dark zone, giving one group the name ‘Zonal pelargonium’. In some hybrids the leaves exhibit both zoning and variegation, producing fantastically vivid patterns that include reds and browns where the zone overlaps the white or green part of the leaf. Added to this, many pelargoniums have strongly scented leaves, found pleasant by most people, but not always. Some scents are like fruit, others like spices or chemicals; a few might be described as goatlike or catlike. Some species even have the fascination of night-scented flowers, similar to jasmine or honeysuckle. They are the gems of any collection.

One final plea for the use of the correct name. If pelargoniums are seen as one coherent group of plants, all bearing the same name, the range of the genus can really be appreciated. The main cultivated groups are the Zonal or bedding pelargoniums, the Ivyleaved, trailing pelargoniums, the beautifully marked Regal pelargoniums and the interesting Scented-leaved pelargoniums. Consider them all as brothers and sisters of the same family, and look at their common features rather than their differences. It will be seen that the pelargonium is a versatile plant, and can be developed both for its flowers and its foliage: an attribute not found in many other plants.

The pelargonium is closely related to the geranium. In botanical classification they are two genera in the family Geraniaceae, which has three other members: erodium, sarcocaulon and monsonia. Erodiums look like small versions of geraniums, and are useful plants for rockeries and alpine gardens. These three groups are known as storksbills (pelargoniums), cranesbills (geraniums) and heronsbills (erodiums), from the shapes of their seedpods, which are supposed to resemble the beaks of those birds. Geranium has by far the largest number of species: about 400; while pelargonium has about 250. By contrast, there are about 60 erodium species, 30 monsonia and only 15 sarcocaulon. However, the number of varieties of plants available in the pelargonium and geranium genera is on a completely different scale: there are about 300 known cultivar names of geraniums, while the number of known cultivar names of pelargoniums was estimated in the year 2000 to be anything up to 25,000.2 This may be misleading, as it is not known whether the names are all valid, and most of the plants certainly no longer exist, but it shows how much hybridisation has gone on over the last 200 years.

3. Seed pod of P. capitatum. The shape gave the plants the name ‘storksbill’. (Geraniaceae Group Slide Library)

Pelargoniums first appeared in Europe in the seventeenth century, brought back by Dutch traders from their settlement at the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. They returned with whatever they thought could be useful, which included plants that might be eaten or used as medicinal herbs. They were grown in botanical gardens and sent to other European countries, particularly France and Britain. As they became more sought after for their decorative value, pelargoniums became popular with collectors for the same reason they have always been popular: they were attractive and easy to grow. However, because they needed to be kept under cover in the winter in northern Europe, only wealthy collectors had the opportunity to grow them for more than one season, and this gave them the status of exotics.

By the 1840s pelargoniums were cheap enough to be taken on by competitive flower growers, known as florists, who competed with each other to produce better novelties and more variety in colour and patterning. By the middle of the century they became recognised as the perfect plant for the bedding craze that was invading every garden, following their use in parks. They developed further as outdoor decorative plants when the mania for the coloured-leaved varieties hit the gardening population, and then there was no going back. By the end of the century, with small conservatories on the back of every middle-class house, they became known as indoor plants and yet more classes were developed. Throughout this time, however, the species plants continued to be grown by minorities, and interest was shown sporadically in using them for hybridising. By the twentieth century the attraction of pelargoniums had reached Australia and the United States as well. In temperate climates pelargoniums could be kept outside all winter, which meant they could be planted as permanent shrubs along streets and in gardens. They were also popular with flat dwellers in Europe, as they would happily cascade down balconies from window boxes. In each country, pelargonium enthusiasts developed their own breeding programmes, producing characteristically different groups of plants, which were eventually exported abroad and again used to hybridise with plants developed there.

To understand the variety in this huge family, and see how interesting and enjoyable they can be to grow, we must go back to the beginning of the gardeners’ love affair with the plant and see what delights appeared along the journey from the seventeenth century to the twenty-first. Few gardeners in the early days could have imagined how the straggly, weedy specimens they saw flowering sporadically in northern gardens could be turned into the universally useful plant we have today. But there was a germ of an idea in the minds of the wealthy plant collectors and nurserymen of the eighteenth century. They recognised the potential in the very brightness of some of the flowers: the vivid red is a colour not often seen in nature; and other species have pink, white or lilac flowers with magnificent feathering in magenta or purple on the top two petals. Very soon it was discovered that the number of different species was in scores rather than dozens, and eventually proved to be hundreds. But it was the gardeners of the nineteenth century who recognised the commercial potential of the plants, leading to an explosion in the number of varieties, and producing a legacy for the gardeners of the twentieth century, who wanted low maintenance and high colour.

In essence, the pelargonium has established itself as one of the ideal plants for all gardeners. It has greater variety than the fuchsia or carnation, blooms longer than the chrysanthemum or dahlia, is perfect in a greenhouse or conservatory, and is easier than the rose to grow to perfection. It could hardly be better known, but how well do we know it? This book came about because when I started growing pelargoniums in the early 1990s I wanted to find out more about the old varieties and how they were used to produce the modern ones. There was no book that told me this. Some nursery catalogues purported to give dates when a plant was introduced, but it was difficult to verify these, and information in some books did not always corroborate the ‘facts’ in others. Most perplexingly, they all gave the same basic historic origins of the plants, but then left the history dangling somewhere about 1700, referred to books on ‘geraniums’ in the 1820s and never tied this information to the modern plants that seemed to ‘spring up fully formed’ in the 1990s. I therefore ploughed my way back through Victorian gardening magazines and trawled the libraries for books written in the 1950s and 1960s, in order to piece the information together.

The genus pelargonium is greatly varied; that is its beauty, its fascination and its usefulness. Some species have been used for hybridising much more than others, for reasons that will be explained. This book concentrates on them because it is a book for gardeners and those with a general interest in garden history. The classification of pelargoniums has always been in dispute and is still not universally agreed. The text will explain the reasoning behind the different attempts at classification, but the technical details can be found in the appendices. The botanical classification, however, is one thing; the gardeners’ and nurserymen’s grouping is another. Zonals, Regals, Angels, Scented-leaved, Uniques, miniatures, dwarfs, Ivy-leaved, coloured-leaved and of course the species are some of the names known in Britain. In Europe, Australia and the United States, other names are used too. Many plants will fall into two or more groups. Names may be Latinised and sound like species, but may be hybrids; other names have been used for several different plants over the course of three centuries, and there will probably be no proof that a modern plant sold under a particular name will be the same as a plant with that name in an old nursery catalogue. Show secretaries maintain their own listings, which are only useful for their own members. Nurseries classify their plants into groups, generally according to purpose. A glossary is therefore provided to explain the terminology, but not a classification of cultivars, as none exists that will satisfy everyone.

Throughout the text there are ‘Plant Profiles’ which appear in boxes. These are a selection of pelargoniums, featuring the main species used in hybridising and therefore the ancestors of the familiar modern plants, as well as examples of some of the groups of pelargoniums grown today. Most plants are still obtainable now from specialist nursery catalogues. They therefore provide a living history of the pelargonium and would be a good base for anyone starting a collection.

I hope this book will provide a link between botany, history and horticulture, and that in reading it gardeners, horticulturalists and botanists may be more inclined to appreciate the work and enthusiasm that has gone into producing modern pelargoniums and so may understand their plants better. Much of the plants’ history is lost forever, due to the secrecy of early growers and lack of interest by later ones. Certain characters will emerge as pioneers, who saw the pelargonium as something special, with an almost infinite potential for development. It is their story as much as the pelargonium’s. For whatever reasons, they used the plants for their own purposes and their own pleasure. They developed a passion for one of the most versatile and extraordinary plants we as gardeners will ever know.

A Note on Terminology

For the general reader who is not a botanist, it should be explained that botanical names consist of two words in Latin form, the genus (i.e. Pelargonium, usually written in italics and with a capital letter) and the species (e.g. inquinans, also italicised, but starting with a lower case letter). The species name either describes the plant (e.g. inquinans means ‘staining’ because of the sap causing a stain) or sometimes comes from a proper name, which may be that of the discoverer of the plant or someone else significant (e.g. fothergillii, after Dr Fothergill who raised the plant). If the plant is a hybrid (i.e. its parents are different species) its name is written with an × before the specific name (e.g. Pelargonium × fragrans). A cultivated variety of a plant is known as a cultivar, and its name is written in quotation marks after the botanical name (e.g. Pelargonium × hortorum ‘Paul Crampel’). In this book, to avoid repetition, most Pelargonium species and hybrids will simply be written using the specific name in italics. Cultivar names will usually appear with capital letters but without quotation marks.

Splendid Curiosities

The Sad Geranium

There is of late brought into this kingdome, and to our knowledge, by the industry of Mr John Tradescant, another more rare and no less beautiful than any of the former; and he had it by the name of Geranium Indicum noctu odoratum: this hath not as yet beene written of by any that I know; therefore I will give you the description therof but cannot as yet give you the figure, because I omitted the taking therof the last yeare and it is not as yet come to its perfection.1

The plant being described is then said to have tansy-like divided leaves and tufts of yellow flowers with a black-purple spot in the middle, ‘as if it were painted’, and is named the Sweet or Painted Crane’s-bill. Such was the earliest pelargonium to be identified in Britain. It was a strange plant, quite unlike any modern pelargonium, but although it could be said to be a distant cousin of many other pelargonium species, it is unlikely to be an important ancestor of modern hybrids, although some influence cannot be ruled out. Yellow-flowered and night-scented, it disappears below ground for a large part of the year. However, it has a curious charm, and its story must be told because it always appears at the beginning of accounts of the history of pelargoniums and needs to be put into context. It is now called Pelargonium triste, but in the tradition of botanists before the time of Linnaeus it had several earlier names.

The plant was seen in the garden of John Tradescant (c. 1570–1638) in Lambeth, south London, in 1632, and was described in the 1633 edition of John Gerard’s Herball. A herbal was a reference book for herbalists and apothecaries, who in the seventeenth century performed many of the functions of modern-day doctors and pharmacists. John Gerard (1545–1612) had been gardener to Lord Burghley and also had his own garden in Holborn, London. Gerard’s Herball was published in 1597 and claimed to list all the plants known in Britain at the time. By 1630 it was out of date, particularly as many of the illustrations were already old when they were first used. Gerard had died in 1612 and the revision was entrusted to Thomas Johnson (c. 1600–44), an apothecary practising at Snow Hill, London. He had already made detailed studies of plants in Kent and on Hampstead Heath, and was an enterprising businessman who attracted people to his shop with curiosities, such as exhibiting the first bananas to be seen in Britain. The bananas had come from Bermuda and stayed in his shop for two months before they were eaten.2

P. triste

(The sad or dull pelargonium, after the colour of its foliage)

Pelargonium triste from Jacques Cornut’s Canadensensium plantarum, Historia, of 1635. (RHS Lindley Library)

A tuberous-rooted, night-scented, feathery-leaved plant with flowers of yellow, green or black. Its foliage periodically dies down and it has not been widely used for hybridising. Its interest lies in its being the first pelargonium to be recorded as growing in Britain, in 1632.

4. John Tradescant’s house in Lambeth, the site of the first pelargonium recorded as being grown in Britain. (Print from a drawing by John Thomas Smith (1766–1833)/Museum of Garden History)

Johnson was required to produce the new edition of the Herball in one year, which was extraordinary considering its size. The work he did can be seen because the amendments and additions are marked in his edition to distinguish them from the original entries. Johnson was about 30 years old and his work would have guaranteed him a good future as both a herbalist and a writer, but he was wounded during the English Civil War in 1643, fighting for the Royalists at Basing House in Hampshire, and later died of fever brought on by the injury.