Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Gardening is one of the most popular leisure activities today and most people take it for granted that suitable plants, equipment and information are easily available. This was not always the case. Anne Wilkinson's engaging book recreates the world of amateur Victorian gardeners – those who had no idea how to start gardening, and no information to help them. In the 1860s gardening was mainly the preserve of professionals who worked on large estates, but a new breed of gardeners was emerging – ordinary householders. Their gardens range from country cottage and rectory gardens to urban gardens behind terraced houses. With no help from the professionals – who refused to believe that gardens in towns were a practical possibility – those innovators laid down the foundations for modern amateur gardening as it is today. This book, richly illustrated with images from contemporary magazines and other sources, explores their journey to create their own piece of England's 'green and pleasant land'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

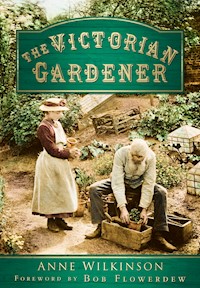

THE VICTORIANGARDENER

THE VICTORIAN GARDENER

ANNE WILKINSON

FOREWORD BY BOB FLOWERDEW

Front Cover: An Old Man and his Daughter Gardening (coloured) by Peter Henry Emerson (Private Collection/Bridgeman Art Library)

First published in 2006

This edition first published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Anne Wilkinson, 2006. 2011, 2013

The right of Anne Wilkinson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9571 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

To

Richard Allfrey

1947–2004

Contents

List of Colour Plates

List of Black and White Illustrations

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part One: The Gardeners

1.

‘The Home of Taste’: How Gardening Enhanced Domestic Life

2.

‘Every Man his own Gardener’

Part Two: Learning to Garden

3.

The Quest for Information

4.

Nurserymen, Seedsmen and Florists

5.

The Hardware of the Garden

6.

Societies, Shows and Competitions

Part Three: Creating the Garden

7.

The Front Garden

8.

The Pleasure Garden

9.

The Vegetable Garden

10.

The Fruit Garden

11.

The Flower Garden

12.

The Natural Garden

13.

The Rose Garden

14.

The Water Garden

15.

The Exotic Garden

16.

The Indoor Garden

Epilogue: What the Victorian Gardeners Did for Us

Appendix 1. Victorian Gardening Magazines

Appendix 2. Suppliers and Places to Visit

Notes

Bibliography

List of Colour Plates

1 & 2.

Details from William Brown’s Louth panorama

3.

Painting of the Butters garden at ‘Parkfield’

4.

Painting of the Butters garden at 41 King Edward Road

5.

Ornamental foliage

6.

Rockery at St John’s College, Oxford

7.

Inside a late Victorian greenhouse

8.

Artist’s impression of Shirley Hibberd’s front garden

9.

Portrait of James Shirley Hibberd

10.

Varieties of Shirley poppies

11.

Varieties of florists’ pelargoniums

12.

Varieties of aubergines

13.

Varieties of melons and tomatoes

List of Black and White Illustrations

1.

Woman gardening in an urban garden

2.

Topiary shaped like a table and glasses

3.

A family seated in front of a summerhouse

4.

A couple growing cabbages on an allotment

5.

Edward Beck

6.

A gardener and boy with their tools

7.

Shirley Hibberd’s garden at Stoke Newington

8.

A Hampshire cottage garden

9.

Revd Henry Honywood D’Ombrain

10.

George Glenny

11.

Charles Turner

12.

George W. Johnson

13.

A ‘Fingerpost’ from the

Floral World

14.

B.S. Williams

15.

The Reading offices of Suttons Seeds

16.

Seed advertisement with animated medals

17.

Florists’ carnations

18.

Alfred Smee

19.

Three types of rake

20.

The ‘Tennis’ lawnmower

21.

A watering can for seedlings

22.

Advertisement for the ‘Sphincter Grip’ hose

23.

Diagrams for making seed boxes

24.

Advertisement for Jensen’s Guano

25.

H.A. Needs

26.

Fumigating an amateur’s greenhouse

27.

Advertisement for Birkenhead’s beetle traps

28.

An anti-cat contrivance

29.

William Edgcumbe Rendle

30.

Rendle’s protector for small plants

31.

A local flower show before judging

32.

Chrysanthemums being grown for shows

33.

Edward Sanderson

34.

The Bloomsbury Flower Show

35.

Shirley Hibberd’s planting plan

36.

Shirley Hibberd’s front garden

37.

A couple standing in their front garden

38.

A suburban parterre with an observatory

39.

Design for a villa garden

40.

Croquet in Alfred Smee’s garden

41.

Robert Fenn

42.

A bunch of scorzonera

43.

Varieties of gourds and pumpkins

44.

Varieties of apple

45.

Reversible fruit ‘walls’

46.

The Queen pineapple

47.

George McLeod

48.

Elizabeth Watts’s diagram for a ‘set garden’

49.

Arthur Launder

50.

The geranium pyramid

51.

Bedding plants in the Butters garden

52.

Formal planting round an urn in the Butters garden

53.

Revd Henry Jardine Bidder

54.

Alfred Smee’s fern glade

55.

Diagrams for making rustic tables

56.

The rustic garden house and prospect tower

57.

Alfred Smee’s summerhouse and hermit

58.

Design for a rose garden

59.

Varieties of roses

60.

Revd Samuel Reynolds Hole

61.

Pillar and festoon roses

62.

Cape pond weed in a container

63.

A rustic aquarium

64.

Masdevallia orchids

65.

Pitcher plants

66.

A collection of cacti in a greenhouse

67.

An outdoor bed of succulents

68.

Exotic plants in a window case

69.

A family in front of a home-made window garden

70.

Moss-gathering blades for country walkers

71.

The ‘Cazenove flower rack’

Foreword

The Victorian gardeners created our modern gardens. Little we now do horticulturally was not already being done back then, and back then it was often being done better. We probably grow fewer varieties of plants than they did, and we certainly no longer need to crop our gardens over such extended seasons, thanks to transport and refrigeration. We have other advantages, especially with modern clothing, electric heating and ventilation, legally enforced seed purity and germination rates, and health and safety regulations! But in all the basics we are continuing exactly as they did, though to our minds usually on a much more humble scale than what was so often perceived as ‘Victorian gardening’.

And that is what is so fascinating about this book: Anne Wilkinson has painstakingly collated scattered fragments of evidence to re-create the early evolution of our gardens. Not of those of the grand and stately homes and great botanical institutions, but of those gardens belonging to us, the real gardeners. Extracting pertinent snippets from the books and magazines of the time, Anne has carefully built up a cohesive history not only of how we gained gardening both as a hobby and as a profession, but also of how we gained our various sorts and types of gardens. From the early cottage and town house beginnings through to such refinements as the Water, Rose and Exotic, she traces each theme and its development. Of course I was particularly interested in the Vegetable and Fruit Gardens but was drawn in by all the other sections, especially the second part, ‘Learning to Garden’.

But let me leave you now to enjoy it all for yourself, reminding you only that this book explains how we derived our knowledge of plants and methods from the hard work and tenacity of just a few generations of far-sighted men and women. It is humbling to realise how much we owe them. As someone once said, truly, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Bob Flowerdew

Dickleburgh

Norfolk

July 2005

Preface

This book is a different approach to Victorian gardening. I have chosen to emphasise the work of amateur gardeners and show how they came to be the primary focus of both the retail market and horticultural publishing. Along with the main text, readers will find mini-biographies of some of the most important players in the story. Many well-known names, however, such as Loudon, Robinson, Jekyll, Paxton and Lindley, do not feature in these, as their lives have already been covered elsewhere. I have chosen to focus on lesser-known gardeners, from wealthy landowners to working people, who all had extraordinary enthusiasm and ability to persevere in their ambitions and encourage others to do the same. There are many people mentioned in the text on whom I would like to have given more information, but I looked for it in vain. They produced a book or two and then, like their gardens, they disappeared for ever. The exception is the most important amateur of all, Shirley Hibberd, on whom I have plenty more information and whose story deserves, I feel, to be told in full in a future book.

As well as the biographies and the main narrative, readers will find Tips and Comments from our Victorian gardeners, many of which are as relevant today as they were when they were written. I have also tried to give a good account of the Victorian gardening magazines, which are the key to any research on the subject, and I hope the details given in the Appendix will help writers in the future. There is much more to discover in their closely printed pages and they could be the basis of many more books and research projects. Finally, I have listed places to visit to see Victorian gardening re-created today, and a list of suppliers to help put into practice some of the ideas described in these pages.

Anne Wilkinson

Upminster

October 2005

Acknowledgements

This book began as a thesis for the Open University many years ago and I would therefore like to thank John Golby and Bill Purdue, my supervisors, for their guidance, interest and enthusiasm in steering me through the technicalities of academic research. I also value the co-operation and friendship of Julia Matheson, a fellow researcher at the OU, who was one of the few people I could discuss Victorian gardening with, knowing she would be interested.

My research took me to many corners of dusty archives and libraries and I never failed to marvel at the knowledge and interest shown by the curators. Both the Lindley Library and the British Library moved to new buildings during the time I was working in them, and I praise the ingenuity of the staff in never failing to find the requested documents in the apparent upheaval. I also became a regular customer at the Hackney Archives, whose help was invaluable, and in particular I would like to thank Isobel Watson of the Friends of Hackney Archives for her early support and encouragement. The Museum of Garden History also proved a fund of treasures, and I especially thank Philip Norman for his detailed assistance. Similarly, much quirky material waited to be discovered at the John Johnson Collection of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, whose staff were also generous with their help.

A huge amount of help, too, was given by Tim Rumball at Amateur Gardening in allowing me to plunder the magazine’s archives and use its illustrations. I am also grateful to Michael Riordan at St John’s College, Oxford, for information on H.J. Bidder, and to George Butters Esq., for information on the Butters family and for allowing the use of the Dommersen portraits. Similarly, I thank Louth Town Council for permission to use the Panorama, Tim Evans for Birkenhead’s fern book, Gavin Weightman for good advice, and Suttons Seeds and Crowders’ Nurseries for their catalogues. I could not have produced many of the illustrations without the instruction and support of Trevor Jackson, to whom I am also very grateful. Lastly, I thank Jaqueline Mitchell for her faith in agreeing to publish the book, and the unfailing support of my friends and family in believing in me, in particular my daughters, Isabelle and Florence Allfrey, whose good humour and practical support always keep me going.

Introduction

The Gardens of Heligan, Alton Towers, Biddulph Grange, Waddesdon Manor, Normanby Hall: just some of the great gardens of the Victorian age. But what about the gardens that were not so great, the gardens belonging to ordinary people? The Victorians were ambitious and the middle classes were rising classes; the working people slowly gained independence and income, and they too wanted their luxuries and their status symbols. A garden seemed to be something everyone in Britain considered essential. It was part of the home and one of the novelties of the age. As exciting plants and patent inventions were released onto a newly created retail market, it appeared that gardening held an interest for people of all classes.

But how did novice gardeners know what to do if they could not afford skilled staff to work for them? Gardening was also time-consuming, and there were few labour-saving devices in the early part of the century. There were no TV gardeners, no glossy magazines, no easy-to-follow books, no garden centres, no Internet. It was ‘do it yourself’ before the phrase was invented. Extraordinary though it may seem, the term ‘amateur gardening’ was not used before the 1850s. Certainly there were plenty of amateurs who were gardeners: florists, botanists, cottagers, allotment-holders, ladies, clergymen, all sorts of people who grew things for pleasure. However, most of them grew only certain things: florists grew florists’ flowers, cottagers grew vegetables and a few decorative hardy plants, wealthy collectors grew zonal pelargoniums or cape heaths. The working classes grew gooseberries and currants and a melon on the compost heap: they would not think of grapes or nectarines; they would not even think of tomatoes. This was not just a matter of money; it was a matter of aspiration.

The difficulty of finding information amid the wealth of resources highlights another problem with the terminology of horticultural history. There is a difference between ‘garden history’ and ‘the history of gardening’. ‘Garden history’ seems largely to be used to mean the history of garden design. This is an interesting and useful study, but many people who indulge in it seem to know little of either plants or the practical side of gardening. Phrases such as ‘the social history of gardening’ seem to be an attempt to look beyond pure design, but authors are often reluctant to go outside the great estate gardens or the walled kitchen gardens, because of course they are usually well documented and easier to research. It is now time to look further into social history to find out how amateur gardening fitted into people’s lives, and discover new facts about the names we frequently hear mentioned, but so rarely connect with real people.

The 1851 census for the first time recorded more people in Britain living in towns than in the countryside. The structure of society was changing, and with those changes came new ideas and new ambitions. This is the story of how gardening became one of the things that anyone could do. People from all classes became amateur gardeners. The wealthier still employed people to work for them, but they began to take more interest in and responsibility for the design of their gardens and choice of plants. The less well off learned the skills of gardening themselves, demystifying the secrets of gardening previously retained by the professionals. In the process, gardening brought people together as equals, which was not easily accepted in the 1850s. This is the story of the writers and gardeners who had the vision to realise that gardening could be a pleasure in itself:

This outdoor life not only keeps the blood in a healthy glow, and the brain active in its search for knowledge, but … the meanest tasks are elevated even to dignity by the fact of their necessity. Hence, a man who is a thorough gardener feels no shame in handling the spade, or in wheeling rubbish to the pit; for though his means may enable him to enjoy all the refinements of life, it is his pride that there is not one manipulation but that he can perform himself, and so a brown skin and hard hands give him no fear that he shall lose his claim to the title of gentleman. And the world is very forgiving on this matter – its sympathies are with a gardener!1

Many people live in Victorian houses and carefully restore them to how they think they would have looked in the nineteenth century, but few try to re-create Victorian gardens. The perception is that they were all bedding plants and ornaments, but this is not entirely accurate. Of course the Victorians liked their formal flower beds and their standard roses, but they also loved the wild and the exotic, the hardy perennials and the florists’ flowers. They enjoyed gardening a hundred and fifty years ago for the same reasons as we enjoy it in the twenty-first century, and it was their hard work and persistence against all the opposition that gives us the vastly superior opportunities we have today. We owe it to them to understand how this came about.

PART ONE

The Gardeners

CHAPTER ONE

‘The Home of Taste’: How Gardening Enhanced Domestic Life

Gardening became popular in Britain in the nineteenth century because it was the right place and the right time. The temperate climate, abundant rainfall and a variety of soil conditions meant that a suitable habitat could be found for almost any plant that was introduced. Skills in botany and horticulture were well established and the challenges posed by new plants were welcomed by gardeners and nurserymen alike. Britain’s position as a centre of world trade meant that the people were used to new products and ideas, and they were quickly absorbed into their lives. By the mid-nineteenth century, Britain was a wealthy country; by the end of the century, even the lower middle classes took novelties for granted and were eager to show them off. But no one wanted to fall into the trap of appearing ‘vulgar’, and they were happy to take advice on taste and style from newly appointed experts. It was inevitable that decorative plants would become one more consumer item on the shopping lists of those with money to spend.

The Victorian home was a refuge from the outside world, a kingdom in itself, ruled over by the head of the family and inhabited by his subjects. The ‘home of taste’ was said to be ‘an anchorage when life becomes a hurricane’.1 Possessions showed status: a man would be judged by the clothes worn by his family, the furniture and ornaments in his drawing room and the appearance of his garden. Although nominally under the control of the man of the house, the day-to-day running of the home was undertaken by the wife. The garden, therefore, as part of the home, often came under her domain, and women’s attitudes to gardening give us insights into how amateurs went about creating gardens in the nineteenth century.

The development of amateur gardening was closely related to the growth of housing, yet while there is plenty of information on how Victorian towns and suburbs developed and how gardens related to the pattern of streets and houses,2 there is little information on how the gardens were actually used. This has led to a belief that gardening did not take place in towns at all in the nineteenth century, and that amateur gardening did not start until much later. This view appears to be supported by the fact that the Gardeners’ Chronicle, often regarded as the ‘bible’ of Victorian gardening, devoted little space to town or amateur gardening until late in the century, when forced to do so by popular demand.3 However, the Chronicle was operating with its own interests in mind and, as will be seen in Chapter Three, these did not include people who had small town gardens.

A suburban garden in the 1890s. Women were often the chief gardeners in the home and some of the earliest amateur writers. (Museum of Garden History)

Yet these small gardens did exist and became an essential part of the landscape of all towns. By the 1850s building land in towns had became scarce and houses were built closely together in a uniform pattern, on as small a scale as possible. The market gardeners and nurserymen on the edge of towns were driven out by high land prices and worsening pollution, making it impossible to grow food or keep cows for fresh milk within walking distance of the centre of town. For the first time, large urban areas became purely residential. The repeated pattern of rows of houses, topped with chimneys and interspersed with small gardens, stretched as far as the eye could see. The world became dark. Soot made the buildings black and fog often obscured the daylight. Industry and commerce governed a world regulated by railway time. Even the names of the new synthetic dyes invented to brighten up life reflected the world in which they were produced: Manchester Brown, London Dust and Dust of Ruins.4 No wonder people living in these new houses wanted to retain a link with the countryside and create a little colour in the drabness.

But in cultivating a garden, the Victorians were not simply indulging in nostalgia for the countryside. British people felt a deep need to establish an ‘estate’ of their own, however small. If an Englishman’s home was his castle, then the garden was his country estate. British social structure had developed differently from other European countries,5 which may be what makes amateur gardening so peculiarly British.6 Traditionally farms and estates in Britain remained intact for generations, passing in entirety to the oldest son, while younger sons left the land and sought other occupations. Landowners remained powerful and became patrons of the surrounding communities. In many European countries, however, land was divided among all children on the death of a parent, creating ever-diminishing farms and smallholdings, often barely providing a living above subsistence level. Whereas landowning in England symbolised power, in many other countries it symbolised drudgery and became a burden. When the English middle classes obtained their individual terraced houses or villas, with a rectangle of garden attached, they saw it as a miniature country estate where they could indulge their individuality and be their own masters, whereas the European who was freed from his family smallholding immediately graduated to a town apartment with no more than a balcony from which to look out over his shared urban domain.

The realities of town living in the nineteenth century were not very pleasant. There was constant pollution from soot, causing dirt and fog. There was overcrowding, and dirty, smelly streets and heavy traffic. But living in town was a necessity for being near work before cheap train fares made it possible to commute. The ideal compromise for people who could afford it was the suburb. John Claudius Loudon (1783–1843), writing in 1838, explained its attraction: ‘Towns, by the concentration which they afford, are calculated essentially for business and facility of enjoyment; and the interior of the country, by its wide expanse, for the display of hospitality, wealth and magnificence, by the extensive landed proprietor: or for a life of labour and wealth, but without social intercourse, by the cultivator of the soil. The suburbs of towns are alone calculated to afford a maximum of comfort and enjoyment at a minimum of expense.’7

Constant washing and keeping hands smooth and soft by a never-failing use of Vaseline or a mixture of glycerine and starch, kept ready on the washstand to use after washing and before drying the hands – are the best remedies I know. Old kid gloves are better for weeding than the so-called gardening gloves; and for many purposes the wash-leather housemaid’s glove, sold at any village shop, is invaluable.

Mrs C.W. Earle, Pot-Pourri from a Surrey Garden, p. 116

In the 1830s Loudon wrote The Suburban Gardener for the middle classes, who found it convenient to live in small ‘satellite’ settlements outside London and other large towns. They were very different from the suburbs that would surround towns without a gap of country by the end of the century: this must be borne in mind when reading books and magazines described as being ‘for suburban gardeners’. The late-nineteenth-century suburb was a commuter-land of small terraced houses close to railway stations where the garden could be measured in square feet rather than the quarter or half acre common to Loudon’s suburbia.

But could these terraced-house ‘gardens’ be used as gardens? We think there is nothing odd in calling a small yard at the back of a town house, or even a balcony with a few pots on it, ‘a garden’. The space behind a Victorian terraced house, however, was unlikely to have been regarded as a garden until well into the second half of the nineteenth century. Earlier, it would have contained the privy, the only lavatory for the house, and the whole of the ‘back extension’ of a terraced house would have been the kitchen, scullery and washhouse. It was not an inviting place for the family to use as a ‘garden’, particularly as the only access would have been through the servant’s quarters (and it probably was just one servant in such houses). Until the necessity for a privy disappeared with the introduction of indoor water closets, the ‘garden’ would never be a place of pleasure.

As to how these ‘gardens’ were used, once they were considered suitable, there was probably as much variety as there is now: some people enjoy cultivating them, others pave them over and use them as dog runs, and some do nothing, so they simply become patches of weeds. There would have been more scope for a real garden in the semi-detached villas which occupied wider spaces and had side access. In either case, houses were not usually owned, but held on leases for several years or months. It was not practical to invest too much money in the permanent features of a garden. This was one reason for the popularity of bedding plants: they only lasted one season, so could be bought when needed and then discarded when a family moved on. Even the more exotic subtropical plants could be regarded as temporary, as it would take a skilled gardener with access to a glasshouse to keep them alive for more than a year or so. Similarly the urns, pots and statues used decoratively could be taken away, along with the other furniture, when the family moved.

Once people had gardens, they had to learn how to look after them. In the early part of the century, those with a rural past would remember the great gardens of their family patrons, and the cottage gardens of their own parents or grandparents. But by the mid-century, with less memory to rely on, people began to copy the great gardens in towns: the parks. Municipal parks were created to provide fresh air and exercise and to appease the unrest felt when working people protested about the conditions in which they had to live.8 The government gave working people access to open space before they took it for themselves by force. At first parks were modelled on the eighteenth-century landscape style, but as gardeners began to establish themselves as park designers, they took on their own identity, which was maintained beyond the end of the twentieth century. Park garden designs were usually based on shrubs and bedding plants, which became the dominant style for many gardens of the Victorian era.

Topiary of a table and glasses in clipped box. The Victorians loved novelty, and labour-intensive crafts were considered suitable occupations for women. (Amateur Gardening, 31 January 1885, p. 474) (Amateur Gardening)

The Victorians liked to encourage participation in self-improvement, and gardening fitted in with nature study, geology and botany as activities taught to children. Women with time on their hands (and most women in the middle classes had plenty of time on their hands) were expected to be productive in an uncommercial way. Flowers and plants could be drawn and painted; they could be collected, dried or pressed, labelled and put into albums or displayed in frames. For many Victorian women the garden became the focus of their lives. Because it was perceived as part of the home, it was private rather than public, and women had the freedom to express themselves in it without worrying about what other people thought. Considering their clothing and their image of helplessness in the nineteenth century, it may seem extraordinary that women could have even attempted gardening in any practical way. However, nineteenth-century women were used to dealing with life in long skirts and corsets. Servants and farmers’ wives had to take part in hard physical work whether they liked it or not, which shows that it could be done, and many women must have taken to gardening as a release from the formality of the rest of their lives.

One of the gardeners most admired by John Loudon in the 1830s was Louisa Lawrence (c. 1803–55). Although she employed six gardeners in her two-acre garden, she planned and supervised the work herself. Loudon thought she had impeccable taste and used her garden as an example of what other gardeners who may not have her means and advantages could do themselves:

It is worthy of remark, that a good deal of the interest attached to the groups on the lawn of the Lawrencian villa depends on the plants which are planted in the rockwork. Now, though everyone cannot procure American ferns, and other plants of such rarity and beauty as are there displayed, yet there are hundreds of alpines, and many British ferns, which may be easily procured from botanic gardens, or by one botanist from another; and, even if no perennials could be obtained suitable for rockwork, there are the Californian annuals, which alone are sufficient to clothe erections of this kind with great beauty and variety of colouring.9

Loudon’s approval of Mrs Lawrence shows that he was prepared to accept women as equals in matters of gardening taste, whether or not he expected them to go out and weed and dig themselves. When recommending how gardens should be run, he frequently refers to women as essential helpers, particularly for watering and insect-collecting. Loudon’s own wife, Jane (1807–58), certainly was a practical gardener. In Gardening for Ladies she recommends tools and equipment which are suitable for women, including a small spade, clogs to put on over shoes, or a small plate of iron to go under the sole of the shoe, fastened with a leather strap, stiff, thick leather gloves or gauntlets, and a light wheelbarrow. She stresses the benefits to health and even describes the process of digging: ‘A lady, with a small light spade may, by taking time, succeed in doing all the digging that can be required in a small garden, the soil of which, if it has been long in cultivation, can never be very hard or difficult to penetrate, and she will not only have the satisfaction of seeing the garden created, as it were, by the labour of her own hands, but she will find her health and spirits wonderfully improved by the exercise, and by the reviving smell of the fresh earth.’10 Jane Loudon started the Ladies’ Magazine of Gardening in 1842, but because of her husband’s ill health she had to abandon it after a year. It covered the history of flowers and descriptions of gardens, and included letters from other ladies. She clearly felt it was important to concentrate on what women could do, rather than what they could not.

JANE WELLS LOUDON (1807–58)

MRS LOUDON, the wife of landscape gardener and writer John Claudius Loudon, was born Jane Webb and was orphaned at 17, whereupon she took up writing for a living. She married Loudon at the age of 23, when he was 47. She described in her book Gardening for Ladies (1840) how difficult it was for amateurs to learn gardening from professionals. She acted as a secretary and assistant to her husband, and although she started the Ladies’ Magazine of Gardening in 1842, she abandoned it because of the extra work when Loudon became ill. After his death, she finished and updated his books, cared for their garden in Bayswater and brought up their daughter, Agnes. She emphasised the capabilities of women in gardening, stressing the rewards to be had for a little extra effort, and from her instructions it is clear that she was a practical gardener, not just a supervisor.

Another practical woman gardener of the same era was the anonymous author of A Handbook on Town Gardening by a Lady, published in 1847. It was presumably anonymous because the ‘lady’ did not feel it suitable to put her name to something sold for profit. She also wrote about the practical aspects of gardening, although she expected to have a labourer to do the heaviest work, such as digging large holes, but she sounds as if she would certainly have been outside, directing operations. A further woman writer who was prepared to put her name to a book in the mid-century was Elizabeth Watts, who published Modern Practical Gardening in the 1860s.11 One of the best reasons to look at the work of women gardening writers, particularly those in the early part of the century, is that they give us an insight into the problems of all amateurs, both male and female, in having very little information to go on and not being listened to. Almost all the male writers at the time were professional gardeners, botanists, florists or nurserymen, and they assumed that their readership was composed almost entirely of other professionals.

The whole family made use of the garden and helped maintain it. This picture shows a rustic table and summerhouse and the shrub Aucuba japonica, which was particularly suited to town conditions. (Museum of Garden History)

When the Gardeners’ Chronicle started to include articles for amateurs in the 1850s, one was entitled ‘A Word for the Ladies’:

The Gardeners’ Chronicle is indeed, to a great extent, a gentleman’s paper, yet there is much information scattered up and down its pages adapted for the gentler sex. If, when the paper is laid on the table, the ladies who love gardening will favour us with their attention, we shall hope to assist them in their pleasing employment … Ladies are great gardeners on a small scale, and a vast majority of the homes which are made more cheerful and elegant by flowers owe their charm to their hands. They generally love flowers for their own sake, and their attachment is less mingled than that of men with considerations of interest, such as beating their neighbours in their feats of horticultural skill, or adding a respectable adjunct to their domain. A woman looks upon a flower as she does upon a child, with an affection abstracted from external considerations of what trouble it will occasion, or what it will cost to keep. And as her principles are more pure in the department of gardening and its ends, so her pleasures are more simple and deep … The wife, on a fine June morning, is watering and transplanting, and anxiously training up to perfection some floral beauties, and a little help in stooping or carrying mould would then be a great boon. But the husband looks listlessly on and does nothing – or rather, as is too often the case, he grumbles at the time and labour bestowed; and in his careless perambulation sets his foot on the choicest pet of the neatly kept border. But, ‘Sigh no more ladies, sigh no more,’ for you have resources in yourselves in this department which will easily make you independent of all but labours of love, and contented to be without aid grudgingly bestowed.12

By the end of the century, as the position of head gardener in a large establishment was gradually being undermined by amateurs taking over the design of gardens and the matters of taste, so women were able to assume a much stronger position. In the last decade of the century it became quite common to see gardening books by women: Mrs Earle, Miss Willmott and Miss Jekyll became household names,13 at least in upper middle-class households, and all dispensed with old-fashioned head gardeners as decision makers.

The class system in the nineteenth century was far more rigid than it is today. Now people feel free to classify themselves however they want to. A person’s way of life generally depends on how much money they have and how they wish to live. In Victorian times, however, whatever people felt privately, they outwardly kept to a class which represented not the amount of money they had, but the occupation of the head of the family. Servants wore much simpler, drabber clothes than their employers, and many people’s occupations could be determined by what they wore. Similarly, before the 1850s what someone grew in their garden was largely defined by the class in which they lived, and it was not thought desirable to try anything different. Joseph Paxton (1803–65) wrote in the Horticultural Register in 1831 about his idea for communal town gardens to be set up by subscription. There were to be fifty gardens of a quarter of an acre each, but they were to be divided into three or more different areas for different classes of society.

The traditional place for gardening for working people was the allotment. But allotments cannot be taken at face value. Their history is closely connected with the development of poor relief and the changes in farming that brought about enclosed land. Allotments were usually let on condition that the allottees observed rules concerned with church attendance, sobriety and not working on Sundays. Organising such schemes was often a useful occupation for ladies who had plenty of leisure time, or clergymen who wanted to set a good example. Publications specifically for allotment-holders did not start until the 1880s, with the introduction of cheaper magazines such as Amateur Gardening. Before that, most of the information on allotment gardening was aimed at the people who organised allotment schemes and what they thought allotment-holders should be doing, not what the allottees necessarily wanted or needed to know.

Cabbages were one of the most popular crops grown on allotments, as they lasted through the winter. (Museum of Garden History)

Allotments as we know them today are usually on apparent wasteland, but often it is land that was originally common land, used by local people for centuries. Some are known as ‘fuel land allotments’ because rents or profits were used to provide fuel for the poor of the parish. Throughout the eighteenth century schemes were put forward to replace common land taken away from villagers by enclosure. Some schemes allowed land to be given by the parish to individuals, some to be worked communally, but all were based on the premise that the land was in lieu of poor relief. There were other types of scheme set up by private individuals, either for their own workers or for the public in a particular vicinity. Even though the food produced on allotments was an important part of the allotment-holder’s diet, necessity was not the only reason for growing it.

Flora Thompson (1876–1947) said in Lark Rise to Candleford that only the men ever worked on the vegetable plots or allotments, but that ‘the energy they brought to their gardening after a hard day’s work in the fields was marvellous. They grudged no effort and seemed never to tire’.14 Jeremy Burchardt, who has studied nineteenth-century allotments extensively,15 believes that they gave people a source of hope in their otherwise dismal lives, and that the allottees valued both the attachment to the soil and the sense of community in working the land with other people.

Not all rented gardens were allotments: there were pleasure gardens on the outskirts of towns, often known as ‘guinea gardens’ from the annual rent paid for them,16 which were usually let to the families of middle-class tradesmen. They probably fell into disuse when the families stopped living above the shop and bought houses in the new suburbs. They were usually divided by hedges and most had elaborate summerhouses where meals could be cooked and where weekends could be spent. Fruit and vegetables were sometimes grown, but the main purpose of a guinea garden was relaxation away from the town.

Science and technology were instrumental in creating the industrial revolution and also contributed to inventions that changed the face of gardening in the nineteenth century, but the garden itself was a high-maintenance, labour-intensive place compared to what we are used to today. Imagine no plastic, nylon or other man-made fibres. Pots were all terracotta: much heavier than modern ones and of course breakable. Seed boxes would be wooden and susceptible to rotting. Where we use plastic netting and fleece today, the Victorians would use cotton thread and different grades of hessian, the finest known as tiffany. Glasshouses would be made of deal, or pine, which meant regular painting, rather than easily maintained hardwood or aluminium. Watering would be one of the biggest chores. Without running water and convenient garden taps, ingenuity came into play to cut down on the time and energy needed to transport water around large gardens in summer. Similarly, with no electricity for heating, propagating plants out of season and protecting from frost meant that every Victorian gardener had to learn the secrets of insulation and to make full use of warmth from the sun. Candles and oil lamps were both used for bringing on seedlings, and the professional gardeners jealously guarded the secrets of the hotbed, learnt over years of experience. Gardeners had to learn much more about gardening than they do today, with no self-service garden centres with well-labelled plants, ready potted up and just the right size for a small garden; an amateur would have to know what to ask for and the quantities needed. Composts and fertilisers did not come ready mixed and weighed in clean plastic bags; they had to be procured as raw ingredients, carted, stored and put together when needed, without any instructions. For an amateur with no handy reference guide, no easily approachable supplier of appropriate plants, and a garden where a thick layer of soot covered every surface and plant, there were enough problems in gardening to put most people off before they even started.

In economical burning the stuff is made ready first, and a good fire being started, the heap is made up with a covering of turf or damp weedy stuff to shut in the smoke and cause a slow combustion in the way that charcoal is made. The result is a valuable bulk of burnt earth, potash, and charcoal, the finer parts of which are invaluable for dusting seed rows in spring as the young plant is sprouting.

Amateur Gardening, 7 November 1885, p. 326

By the end of the century, however, when the plight of the amateur was recognised and the retailers discovered they had a ready market, gardening brought people together. National societies were formed for those interested in growing particular plants, which meant that professionals and amateurs of all social classes could meet and compete together. It was no longer unacceptable for a working person to grow exotic plants or strawberries or grapes, if he could afford them and had the time to care for them. Conversely, the wealthy were taking pride in their herbaceous borders consisting of plants that had hitherto been the mainstay of cottage gardens. Small conservatories appeared on the back of many houses in the suburbs. Greenhouses and lawnmowers and other gardening equipment was inexpensive and commonplace.

In 1888 Amateur Gardening gave its view on the position of gardening:

A villa garden, as a rule, contains just enough space to be within the means of the owner or occupier to keep in order, and it happens more often than not that he does so even to a lavish extent. In doing so he is only acting in perfect harmony with the natural order of things, and everyone who has the means should certainly strive to have not only his house but his garden beautiful also. As well make a lady’s dress without its lace or other trimmings, or a bonnet without its exterior adjuncts and call it finished, as to consider a home complete in the absence of a neatly laid out garden.17

Gardening magazines of the 1890s even became boring in their uniformity: everyone was interested in the same plants and were all going to the same shows at the Crystal Palace. Gardening had something for everyone and seemed immune to criticism as a social activity. It was healthy, educational, productive and decorative. It provided an outlet for the desire for ostentatious wealth and novelty. With a garden one could have something different and something new every year, or indeed several times a year, or one could perpetuate traditions and re-create the gardens of one’s childhood. In the nineteenth century gardening truly became available to all.

CHAPTER TWO

‘Every Man his own Gardener’

As early as 1767 a book came out called Every Man his own Gardener, sounding as if it would be a guide to gardening for amateurs. Its purpose was ‘To convey a practical knowledge of gardening, to gentlemen and young professors, who delight in that useful and agreeable study’.1 The ‘young professors’ were probably people training to be gardeners, who at the time were often described as ‘professed gardeners’, but who were the ‘gentlemen’? The frontispiece shows two gardeners in breeches, buckled shoes and aprons, digging and hoeing, while a lady and gentleman pass them by on the way to a glasshouse. The sections of the book include The Kitchen Garden, The Nursery, and The Hot-House, and it becomes increasingly obvious that no ‘gentleman’ reading it would have any intention of going outside with a spade to do any work himself. Why then write such a book for ‘gentlemen’? In the Age of Enlightenment many gentlemen were interested in collecting the rare plants coming into the country, but by the conventions of the day they were unlikely to have done any practical work in looking after them themselves.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the word ‘gardener’ did not simply mean someone who enjoyed gardening; it invariably meant a professional gardener, properly trained. He might also be termed ‘a practical gardener’, to distinguish him from a botanist or an amateur. Anyone other than a professional would be described as simply ‘an amateur’ or be given a specific name in the context of gardening, such as florist,2 botanist, or cottager. ‘Amateur’, however, is often used in the 1840s to mean a florist, to distinguish an amateur florist from a professional one, but until the 1850s the description ‘amateur gardener’ rarely occurred. If the meaning of ‘gardener’ is not understood, much of what is written in gardening literature of the time may be misconstrued. The following appeared in a review of James Shirley Hibberd’s book The Town Garden in the Gardeners’ Chronicle in 1855: ‘We cannot, however, say much in favour of [the book], which does not seem to have been written by a gardener, if we are to judge from the plants recommended for cultivation, and from sundry little symptoms which the practised eye has no difficulty in detecting. Gardeners do not talk of “Asderas of suffocated greens” or “Tantalian lakes” or “Stagyrian retreats”, whatever those phrases may mean.’3 Shirley Hibberd (1825–90) was certainly a gardener in the modern sense, but the magazine was deriding him as not being qualified to write about gardening.

There was a traditional rivalry between gardeners and nurserymen, probably because one of the gardener’s perks was to sell plants that were surplus to requirements, thus cutting out the nurseryman. But this was not always allowed. A report appeared in the Gardeners’ Chronicle in 1857 of a gardener who was fined £20 for selling plants to the value of eight shillings, or could alternatively serve two months in prison.4 It was said to be common for gardeners to sell produce to Covent Garden fruit and vegetable market in London during the winter months.

The photographs of organised, hierarchical garden staffs with a head gardener, under-gardeners and apprentices, ranged in lines in front of impressive hothouses, give a misleading impression of what life as a gardener was like. The majority of people with more modest establishments had to make do with only one or two gardeners, or maybe no one qualified as a gardener at all. They were more likely to have used whatever servants were available or who could be spared from their other duties, and training might not be on a formal basis. Edward Beck (1804–61), a nurseryman and florist, found a solution for two unsatisfactory employees: ‘His head gardener did not give satisfaction, not for want of honest desire to please, but his heart was not in his work, and therefore that work did not prosper as it ought. The master did not want to dismiss the man, but things must be altered. He had seen in his groom an interest in garden matters, little things that would have escaped the notice of a more ordinary observer; and to their own surprise the men were retained, their offices exchanged.’5 Mr Beck was an expert on flowers and could train the man to run the glasshouses. Many people who were pure amateurs might have to learn the skills themselves first in order to teach their servants how to become gardeners. It seems that this is exactly what happened when middle-class people moved into suburban houses with medium-sized gardens: big enough to need help, but not big enough to employ a full garden staff.

EDWARD BECK (1804–61)

EDWARD BECK lived at Worton Cottage, Isleworth, Middlesex. He was a Quaker, had been a merchant seaman, and later set up business as a slate merchant and specialised in growing pelargoniums. He was one of the founding editors, and first proprietor, of the Florist in 1848. He wrote Treatise on the Cultivation of Pelargoniums (1847) and ‘A Packet of Seeds saved by an old Gardener’ to improve conditions for gardeners. He won a £7 prize from the Horticultural Society for putting out the best seedling pelargonium and donated it back on condition that others put up the same amount next year. His son Walter carried on the nursery after his death. The Floral Magazine said of Edward Beck, ‘His memory will be long cherished as an upright, intelligent and enthusiastic grower’.

Edward Beck (1804–61). (Engraving from The Garden, 2 October 1886) (Royal Horticultural Society, Lindley Library)

By the 1830s suburban housing was increasing significantly. Loudon thought there was enough demand for a handbook of gardening for those living in the suburbs. He lived in one himself: Bayswater, now very much part of west London. His massive undertaking was eventually produced in two volumes out of a projected three, as he died before the third was written. The Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion dealt with the design and layout of houses and gardens; and The Suburban Horticulturalist described cultivation of fruit and vegetables.6 The third volume would have covered ornamental plants. But who did Loudon mean when he referred to the suburban gardener, and how did he differ from any other gardener? In The Suburban Horticulturalist, Loudon describes his readership as being ‘the retired citizen, the clergyman, the farmer, the mechanic, the labourer, the colonist, or the emigrant’. He went on to say:

The possessor of a garden may desire to know the science and the art of cultivation for several reasons. He may wish to know whether it is properly cultivated by his gardener; he may wish to direct its culture himself; he may desire to know its capabilities of improvement or of change; he may wish to understand the principles on which the different operations of culture are performed, as a source of mental interest; or he may wish to be able to perform the operations himself as a source of recreation and health.7

Note that actually working in the garden himself comes last in the list, almost as an afterthought. Loudon’s villa gardens are described as ranging from ten acres or more, perhaps including a park or farm, down to houses in streets or rows with a garden of one perch to one acre.8 He is writing for a broad spectrum of people who want to learn about gardening, regardless of the size of their garden; in other words, someone we would now call an amateur gardener.

A wall is an ugly thing in a flower garden, although a good protector. To hide its unseemliness, it may be covered with ornamental creepers, or with fruit trees, which none can think an eyesore. A wall of turf may be made lasting under proper treatment. Sow it well with furze seed, when it grows, clip it, and keep the whole surface regularly clipped, and in time it will be like a good-looking green wall.

Elizabeth Watts, Modern Practical Gardening, p. 193

Loudon tailored his gardens to suit his readers. A suburban villa with a one-acre garden could be managed by its occupier, a person of leisure ‘attached’ to gardening, with the help of ‘a couple of labourers’.9 For a terraced house in a street of similar houses, he suggests a garden consisting mainly of trees and shrubs: ‘This garden would be very suitable for an occupier who had no time to spare for its culture, and who did not wish for flowers. It would not suit a lady who was fond of gardening: but for one who was not, or had no time to attend to it, and who had several children, this garden would be very suitable, because it would afford the children abundance of room to play in without doing injury.’10