Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

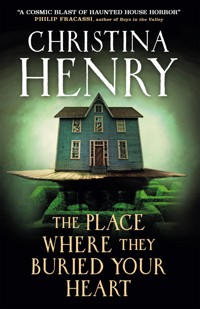

A woman must confront the evil that has been terrorizing her street since she was a child in this gripping haunted house novel, perfect for fans of The Last House on Needless Street and Tell Me I'm Worthless. On an otherwise ordinary street in Chicago, there is a house. An abandoned house where, once upon a time, terrible things happened. The children who live on this block are told by their parents to stay away from that house. But of course, children don't listen. Children think it's fun to be scared, to dare each other to go inside. Jessie Campanelli did what many older sisters do and dared her little brother Paul. But unlike all the other kids who went inside that abandoned house, Paul didn't return. His two friends, Jake and Richie, said that the house ate Paul. Of course adults didn't believe that. Adults never believe what kids say. They thought someone kidnapped Paul, or otherwise hurt him. They thought Paul had disappeared in a way that was ordinary, explainable. The disappearance of her little brother broke Jessie's family apart in ways that would never be repaired. Jessie grew up, had a child of her own, kept living on the same street where the house that ate her brother sat, crouched and waiting. And darkness seemed to spread out from that house, a darkness that was alive—alive and hungry.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Part I: Scattered Memories, Mine and Others 1973–1997

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Part II: Creeping Vines 1997–2006

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

After

About the Author

Also by Christina Henryand available from Titan Books

LOST BOY

THE MERMAID

THE GIRL IN RED

THE GHOST TREE

NEAR THE BONE

HORSEMAN

GOOD GIRLS DON’T DIE

THE HOUSE THAT HORROR BUILT

THE CHRONICLES OF ALICE

ALICE

RED QUEEN

LOOKING GLASS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Place Where They Buried Your Heart

Print edition ISBN: 9781835412640

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835412657

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835416839

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: November 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © Tina Raffaele 2025.

Christina Henry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Designed and typeset in Arno Pro 12/15pt by Richard Mason.

“A house cannot be made habitable in a day;and, after all, how few days go to make up a century.”

—BRAM STOKER, DRACULA

PART I

SCATTERED MEMORIES,MINE AND OTHERS

1973–1997

ONE

1993

I WAS AT HOME, grounded for stealing cigarettes from Johnnie’s corner store, on the day my baby brother, Paul, was eaten by the house at the end of the street. Paul was eight and I was thirteen. I wasn’t there when it happened but it was my fault anyway.

The house, the old McIntyre place, had been abandoned for twenty years when Paul and his friends Richie and Jake snuck in through the back door. They weren’t supposed to get hurt, none of them. It was only a dare, a childish thing. I couldn’t have known what would happen.

Neighborhood teenagers had used a certain broken window on the side for years, had smoked and drank and gotten inside each other’s pants in the dusty, rat-infested living room of the former residents. Those kids always said the place was creepy, that there were bloodstains on the walls. Some of them claimed to have heard noises upstairs, but this kind of talk was mostly dismissed. There was always someone in every group—usually a boy—who wanted to terrorize the girls into squeezing closer, and saying there were noises upstairs was an easy way to do that.

Nobody ever said the house was dangerous—that is, beyond the obvious fact that it was an old, rotting house. More than one kid needed an extra tetanus shot after going in there, but nobody died. Nobody died until Paul.

I should probably say that nobody died because of the thing in the house. Because somebody had died there, that’s for sure. Seven somebodies died there, and they’d died in such horrible ways that no one had wanted to live in the house ever again. Which was why it was abandoned and rotting. Which was why it had become the perfect place for the kids in the neighborhood to have a little thrill of danger without actually experiencing it.

Except for Paul and Richie and Jake. Three went in and two came out and it was my fault.

It was a rambling three-story frame house, unusual in an area that had mostly two-or three-flats made of brick or greystone, canted a little to one side like there was subsidence beneath. Chicago was built on a swamp, so the subsidence kind of made sense, except none of the other houses in the neighborhood tilted that way. As far as I knew, no one ever went up to the third floor. Most kids don’t even like to go into their own attics, never mind the attic of a building that had holes in the stairs.

One time Scott Gunther tried to go up those stairs on a dare and his leg went through the third step. His pant leg tore all the way up to the hem of his briefs and he was pretty embarrassed about that when they yanked him out. The two other boys who’d dared him were laughing until Scott’s eyes rolled up into his head and he collapsed. That was when they realized the broken wood in the step had carved a deep jagged line in Scott’s flesh from his ankle to his thigh and he was bleeding out while they laughed. Scott was a few years older than me, and he never wore shorts again because the little kids would ask him about the scar.

The neighbors across the street, the Rileys, said they heard Paul and Richie and Jake screaming sometime around 3:30 p.m. Mr. Riley was watering the front lawn and listening to the Cubs game on the radio. Mrs. Riley was clipping coupons from the weekly circular at her kitchen table. The window above the sink was open. She told me later that she heard the three boys over the sound of the game and the traffic on the street, even though the kitchen was in the back of the house like most Chicago apartments.

There was an ear-splitting scream, high-pitched and terrified, and Mr. Riley shut off the hose. Mrs. Riley stood up from the kitchen table, her scissors still in her right hand, and went to the front of the house and opened the door.

“Carl, did you hear that?” she called, and she told me her heart felt like it was about to burst right out of her throat, the sheer unnaturalness of the sound spiking panic through her.

Carl stood on the lawn, the hose sprayer in his hand, his head cocked to one side. Mrs. Riley remembered the crack of the bat followed by Ron Santo’s voice lamenting a Cardinals run, and then, she said, “It was pure pandemonium.”

The boys were yelling and crying loud enough to be heard all up and down the block. Mrs. Riley rushed out to the front lawn wielding the scissors. Mr. Riley dropped the hose and ran across the street, pushing open the rusting metal gate.

Mrs. Riley said that she stood there, holding the scissors and not knowing what to do. The Majewskis came out onto their porch holding hands, their faces terrified. They lived to the right of the Rileys, on the first floor, and they were both in their seventies. Mrs. Majewski was so pale that Mrs. Riley was worried she might faint on the spot. Mrs. Majewski wore a pink flowered housecoat and her carpet slippers, and her hair was white and fine and fluttering in the breeze. Mrs. Riley thought she looked like a dandelion with a bent stem.

Ted Dobrowski, who lived on the other side of the Rileys, rushed out his front door. He was in his mid-thirties, divorced, and had one fifteen-year-old son, Alex, who was known as a Problem Child around the block. Ted wore his Sandberg jersey and he held a can of Old Style.

“What the hell, Sheila?” he said, staring across the street at Carl, who was trying to open the front door of the McIntyre place.

There were boards tacked over the frame to keep anyone from going inside. The boards were covered in faded citations that had, as far as anyone knew, never been followed through on. Maybe if the city had done what they were supposed to do and torn down the property years before, none of this would have ever happened.

Ted dropped his beer on the lawn and ran to help Carl.

“Should we call the police?” Alice Majewski said, her voice quavering.

The screams were louder, more frantic, and mixed with the hoarse cries of Carl Riley and Ted Dobrowski calling, “Hang on kids! We’re coming!” and the crack of the bat and cheers coming from the radio.

Sheila Riley said the men got the boards off and Ted Dobrowski ran at the door like a linebacker, shoulder first and legs low, and the door flew open as if by magic.

“And then,” Sheila Riley told me, ten years later, after Carl Riley had died from stomach cancer and Ted Dobrowski’s Problem Child had become my personal problem, “it was even worse. Because the door was open and there was nothing to muffle that sound—the sound of those boys in terror. Carl and Ted just stood there in the doorway, and you could tell they didn’t know what to do. There was this other noise then, this almost-roar, but it wasn’t exactly that. I don’t know how to describe it, except it was like there was a crack in the world. And right before that crack closed up again, I heard him. I heard Paul screaming your name, saying, ‘Jessie, Jessie,’ over and over again.”

* * *

ON THE DAY my brother was eaten by the house at the end of the street I was home, grounded and in a filthy mood.

Paul kept coming to my bedroom, trying to jolly me out from under the black cloud.

“Wanna play Monopoly?” he asked, his brown eyes and the tip of his nose peeking around my door.

“No,” I said. I had my Walkman on, blasting the Black Crowes. I did not want to listen to Paul chattering. I turned the volume up as far as it would go.

I hated having to use a cassette player when all my friends had CDs, but as my mother frequently reminded me, “WE CAN’T AFFORD IT” and “WHEN YOU’RE OLD ENOUGH TO GET A JOB YOU CAN WASTE YOUR MONEY ON THOSE KINDS OF THINGS.” She probably wasn’t yelling at me all the time, but whenever she talked, it felt like she was, like everything she ever said to me was in all caps because I was “GOING TO BE THE DEATH OF HER.”

Paul was her perfect child, the one who did everything right all the time. But maybe I only remember him that way because he never had a chance to grow up and mess up, never had a chance to be a teenager, to change, to make mistakes, to atone, to morph into someone new and more complicated.

His eyes and nose disappeared, but fifteen minutes later he was back again. “Wanna play Life?”

“No, Paulie,” I said. “Get lost.”

He pushed the door open a little farther. I remember him standing there, his black curls spiraling everywhere in the humidity, just like mine. His legs were skinny and scabbed under gray shorts. He always wore his Cubs shirt on home game days, even if that meant he wore it three or four days in a row.

“Mom told you not to call me Paulie. I don’t like it,” he said.

“Whatever, Paulie.” I flopped back on my bed so my eyes burned a hole in the ceiling.

“Jessie, Mom said don’t do it.”

I turned onto my right side so I wouldn’t face the door. The Walkman volume wasn’t loud enough to drown out the sound of him coming around my bed. I closed my eyes, trying my hardest to ignore him. He pushed his hand into my shoulder, shoving me a little. My eyes snapped open.

“You want a black eye, Paulie?” I said, sitting up and menacing him with my fist.

“Don’t call me Paulie!” he said, his tone right on the verge of whiny.

“I’ll call you whatever I want, Paulie.”

“I’m gonna tell Mom,” Paul said.

“I’m already grounded. I don’t care.”

This was a lie. Mom said if I “PUT ONE TOE OUT OF LINE” I’d be grounded for the entire summer. It never pays to show weakness to a younger sibling, though. If they detect a single chink in your armor, they will exploit it.

Paul stood there, staring at me with jaws and fists clenched. He really wanted to slug me, I could tell, but Mom had told him that “gentlemen don’t hit their sisters.” (“What if she’s being a jerk?” Paul had asked. “Not even then,” Mom had replied.)

“Why won’t you stop?” he said.

“Because it annoys you, Paulie. If it didn’t annoy you, I wouldn’t do it.”

I flopped onto my back again, staring at the ceiling. A little brown house spider crawled slowly across the blue paint.

“What if I give you all my baseball cards?”

“No, Paulie. I don’t want your baseball cards.”

“Paulie is a baby name,” he said, desperation evident in his voice. “I’m a big kid now.”

“Oh, yeah?” I asked, sitting up straight with a sudden brain wave. “Prove it.”

“Prove it how?” he asked warily.

“You’ve got to go into the McIntyre place and stay there for a half hour,” I said.

I didn’t think he’d actually do it. Like most of the younger kids in the neighborhood (including myself, a few years earlier), Paul thought the McIntyre place was haunted. He’d probably stand on the sidewalk, looking at the house, for the rest of the afternoon, his teeth chattering while he tried to convince himself to go in before slinking home, defeated, for dinner.

“How will I prove I was there the whole time?” he said.

“You gotta bring Richie and Jake with you,” I said in another moment of light bulb brilliance. It would take extra time for Paul to round up the other two (which meant more minutes out of the house and not bothering me), and also, Richie was a tattler. If they did, by any chance, work up the guts to go inside and didn’t spend the full half hour, then Richie would tell.

In fact, if they did actually fulfill the terms of the dare, Richie would tell, anyway. When his mom asked what he did during the day, he was incapable of lying to her. If Richie said that he and Paul and Jake had gone inside the McIntyre place, they’d all be in trouble, and I was feeling just vindictive enough to want somebody to be in trouble besides me. All the kids were told to keep away from the house because it was dangerous.

When grown-ups said “dangerous,” they meant “structurally unsound.” They didn’t mean the house could devour a child whole.

I didn’t think Paul would tell Richie about the dare. He wouldn’t want Richie to know, because conflicts between siblings are kept between siblings, or at least that was how Paul and I were. Petty arguments were immediately turned over to the court of Mom and Dad, but anything serious stayed between us. It turned out I was right about that, although I didn’t know for a long time.

“If I go in there, if I really do it, will you stop calling me Paulie?”

“Yeah,” I said. There’s not a chance in hell you’ll do it, I thought.

He licked his lips and stood there, shifting his weight from foot to foot, looking uncertain.

“I dare you,” I said.

He walked out of the room and I never saw him again.

But Mrs. Riley told me that right before Paul died, she heard him call my name, call out “Jessie,” as if I could save him from the monster. The last person he thought of was me, the sister who’d sent him there.

* * *

SHEILA RILEY SAID Richie and Jake ran screaming down the stairs, straight into Carl and Ted. The boys were covered in blood and Richie held a scrap of blue cloth in one tight fist, but nobody realized what it was at first.

Jake’s left hand was pressed against what remained of his right arm, a ragged mess of skin and muscle and bone sheared off just above the elbow.

Carl later told Sheila, “I don’t know how that boy was standing up at all, much less running.” Sheila said she thought Jake must have been terrified beyond all reason, and Carl said, “Yes. I think we all were, when we saw the blood and heard their screams.”

Carl and Ted scooped up one kid apiece and Carl yelled for his wife to call an ambulance. Nobody was thinking about Paul then. The adults didn’t even realize Paul had been in the house. Even Sheila Riley, who remembered hearing Paul yell out my name, didn’t think about my little brother.

“There was too much chaos,” she told me. “The two boys were screaming. They wouldn’t stop screaming. Jake, that made sense—he’d been hurt in a way that was hard to comprehend. Richie just seemed to have a few scratches on him, but he wouldn’t calm down. I guess it was because of what he’d seen. I wanted to scream myself when I saw Jake’s arm. I hardly knew how to explain it to the 911 operator. How do you say a little boy lost his arm and that it looked like it had been bitten off?”

Sheila managed to make the urgency of the situation known, because an ambulance did arrive and the boys were rushed to the hospital, both of them refusing to let go of Carl and Ted. By that time half the neighborhood was hanging out their windows.

Not me, though. I was sulking in my room. Dad was at work. Mom was out running errands. Nobody thought that Paul was missing. It was normal for him to spend a summer day out with his friends. Sometimes he even stayed on at Richie’s or Jake’s for pizza or burgers, but he’d call home if he was going to do that.

The phone rang a couple of times while I was in my room, but I didn’t bother picking it up. I wasn’t allowed to talk on the phone—a consequence of my punishment—and I wasn’t going to take any messages for anyone. My parents didn’t have an answering machine, because my father didn’t like them for some mysterious Dad reason. Anyway, Mom had laid down the law and I was going to follow the letter of it. Let the goddamned phone ring.

Mom returned from her errands a couple of hours after Richie and Jake were rushed to the hospital and Paul disappeared forever. I’d heard the ambulance go by, but I didn’t especially take note of it. I was too busy feeling sorry for myself because I’d gotten in trouble.

* * *

THE SHOPLIFT WAS PERFECT—nobody in the store had noticed me slipping the cigarettes into my jeans pocket. My best friend Tara (who had huge boobs already and looked a lot older than thirteen) distracted Marcus Garcia, the eighteen-year-old behind the counter, with some extremely inept flirting and then bought an ice cream bar to cover up our presence in the store.

It was early evening and the sun was still up but the shadows were long. We were so freaking happy to be out of school and ready to do whatever we wanted for the summer.

We left the shop giggling and giddy, high on our own power, and ran to the closest playground to try out our misbegotten booty. Tara had stolen a book of matches from a drawer in her kitchen—her father compulsively collected them from every bar he visited even though he didn’t smoke (he did visit a lot of bars, though). We hid behind a thicket of bushes in the corner of the lot, away from where the little kids played. There were several cigarette butts there in the dirt, evidence of other youthful wrongdoers, and an empty bottle of Malört. There was also a Trojan wrapper, its presence causing a prolonged fit of giggles.

“Who could it be?” Tara asked. “It’s gotta be somebody who doesn’t have a car.”

Everybody knew that if you had a car you could get laid in the back seat. Not a lot of kids had cars, though, or access to them—in a city with buses and trains there’s not really a need, unless you were looking to get laid.

I shrugged. “Alex Dobrowski, probably. He’s only got his permit and his dad won’t let him drive the car since Ted found weed in his room.”

“Yeah, probably,” Tara said, sighing. “He’s so gorgeous.”

“Who?” I said, frowning. “Alex Dobrowski?”

“Yeah, don’t you think so?”

“No,” I said, because I didn’t think it then. I changed my mind later, but I really shouldn’t have. “He’s a loser. He’s never going to go to college or anything or have a future. He’s always getting into trouble for something. He’s got juvie written all over his face.”

“Yeah,” Tara said. “But all the smart guys look like sticks with glasses, and Alex Dobrowski at least has some muscles.”

“I guess,” I said. “Anyway, who cares about him?”

I pulled the pack of Camel Lights out of my pocket. They’d been the easiest to reach and therefore to swipe. After unwrapping the top and tossing the cellophane next to the Malört bottle, I tapped out a cigarette for each of us. I put mine between my lips, the unfamiliar taste of the filter foreign on my tongue. The scent of the tobacco drifted into my nostrils.

“Not like that,” Tara said, adjusting the cigarette in my mouth so it was more centered. She struck the match-book and lit her own, waving the flame out as she took a long drag, then coughed immediately, smoke puffing out of her nose like she was a sick dragon.

I refrained from laughing at her, because you don’t laugh at your best friend, especially when you might look just as ridiculous a second later.

“How is it?” I asked. My heart beat so fast. This would be the first really adult thing I ever did in my life.

Tara’s face squished up. “Kind of gross. Like licking the inside of an ashtray.”

“Oh,” I said, unable to hide my disappointment.

“You try,” she said, passing me the book of matches.

It took me two tries to get the match lit, and I caught a quick whiff of sulfur before bringing the flame to the cigarette tip. I inhaled, slowly and shallowly, wanting to ease the smoke into my lungs instead of forcing it in like Tara. The cigarette end flared. The smoke felt hot and slightly scratchy. I held my breath for a second, letting it swirl around inside me. Then I carefully blew the smoke out of my mouth in a long stream. All my blood felt like it rushed to my head, and I was momentarily dizzy, then elated. I’d done it. I’d taken my first drag off a cigarette. The smoky taste seemed to linger in my mouth, but not in an unpleasant way.

“You looked so cool!” Tara said, shoving my shoulder. “Not like me.”

“Try again,” I said.

Tara looked at the smoldering cigarette in her hand, shook her head, and stubbed it into the dirt. “Nah,” she said. “It’s not for me, I guess.”

I took another drag, savoring the head rush that followed it. And then, at that very moment, Mrs. Ludwig (who was nosy as hell and about a hundred years old to my adolescent mind, but was probably closer to sixty) passed by us on the other side of the fence, which bordered an alley. Her sharp blue eyes widened, and she pointed at me with all the drama of a Salemite accusing a witch.

“Jessica Campanelli!” she said, her reedy voice probably carrying through the neighborhood. “I’m telling your mother!”

And she marched off, a bag of groceries banging against her hip.

“Shit,” I said, stubbing out the cigarette.

“What should we do?” Tara asked.

“You don’t have anything to worry about. She’s not going to call your mother.” This was a simple statement of fact, since Tara’s mother had taken off two years earlier and no one had heard from her since.

“I know,” she said, her brows knitted together. “But you’re going to get in trouble.”

“I always get in trouble for everything. ‘You didn’t empty the dishwasher,’ ‘You didn’t get a good enough report card,’ blah blah blah. It’s not a big deal,” I said, affecting a brazenness I didn’t feel. I handed her the pack of cigarettes. “Hide these for me, will you?”

Tara went home and I went in the direction of my house, but I didn’t go straight there because I wanted to put off the yelling as long as possible. I thought maybe if my mom got tired she might go easier on me, but instead she got herself wound good and tight in the intervening hour. When I finally slinked in the front door, she was a star on the verge of a supernova.

“WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN MRS. LUDWIG SAID SHE SAW YOU SMOKING I SWEAR TO GOD YOUNG LADY YOU’RE GOING TO BE THE DEATH OF ME WHERE DID YOU GET CIGARETTES FROM SHE SAID SHE SAW A BOTTLE OF ALCOHOL TOO WHO BOUGHT YOU ALCOHOL DON’T TELL ME YOU WEREN’T DRINKING SHE SAW IT LET ME SMELL YOUR BREATH YOU’RE NOTHING BUT TROUBLE TO ME.”

She didn’t believe me when I said the bottle of Malört was already there and empty. She didn’t believe that it was the first time I had ever smoked, that I just wanted to try it out. She didn’t listen to a thing I said and then she grounded me for a week and told me I’d better be grateful it wasn’t more.

My mom decided in that instant that I was a Problem Child, just like Alex Dobrowski. Maybe that was what attracted me to him, later, when I decided that boys weren’t useless and I wanted to feel like somebody in the wide world loved me.

* * *

NONE OF US realized Paul was missing until it got close to dinner and he didn’t come home. He was the Good Kid, always letting Mom and Dad know exactly where he was and what he was up to, so Mom was worried when he didn’t call to say he’d be late. I didn’t think Paul had actually gone into the McIntyre house, and I certainly wasn’t thinking about those phone calls I hadn’t bothered answering. Mom hadn’t come home from her errands until after the fuss was over and everyone had gone back inside.

I figured Paul was still hanging around outside somewhere, trying to work up the courage, and that he didn’t want to come home and face me because he was a chicken.

Mom called me downstairs and said “WHERE’S YOUR BROTHER” in that special tone she always reserved for me, and I said, “I don’t know. I’ve been stuck in the house all day.”

There was no way I was going to say I’d dared Paul to go into the McIntyre place. If he got a hangnail while he was out it would be my fault, because everything was my fault.

She turned away from me, heaving a frustrated breath, and checked the Shake ‘N Bake pork chops she’d just stuck in the oven. Then she said “SET THE TABLE” before picking up the handset of the yellow phone that hung on the wall by the yellow refrigerator.

Everything in our kitchen was some shade of yellow (though Mom said “gold”) except the oven, which was black with silver handles. The wallpaper was light yellow with pictures of old-timey things in the pattern—butter churns and spinning wheels and stuff like that. The refrigerator was a brighter yellow, but it still didn’t look like “gold” to me—more like the way a black-eyed Susan looks in the middle of summer. The linoleum was white-and-yellow check, faded in places where our feet tracked across the floor with regularity. The curtains on the window were also yellow, though Mom was an indifferent housekeeper and the tops were often covered in dust because she always forgot to take them down and wash them.

When I was little, I always thought the bright yellow kitchen was a happy place, a place where we laughed and ate delicious food and the sun seemed to shine always. By the time Mom was dialing the phone to call Paul’s friends, I hated the kitchen, hated its forced cheer, hated the way I was imprisoned at the table every night and expected to smile even if I didn’t want to.

I banged the plates on the counter as I took them out of the cabinet and Mom gave me a dirty look as she waited for whoever she’d called to pick up, opening her mouth to reprimand me. She turned her back to me instead, because whoever was on the other end had picked up. I carried the plates to the table and went back for the silverware.

“Melissa? It’s Brenda Campanelli, Paul’s mom? I was just wondering if Paul was over, playing with Richie . . .” She trailed off, and I could hear the sound of Richie’s sister’s voice, but not the words she was saying.

Melissa seemed upset about something, and when she took a breath, Mom said “What?” in a tone that made me pause. Then she said, “Was Paul with them?”

Dread bubbled up inside me. I didn’t know what had happened yet, but I thought one or more of the kids had gotten hurt. My fault. Maybe one of them had broken a leg stepping through a rotting floorboard, like Scott Gunther. Paul was definitely going to tell on me in that case. The rules of secrecy would no longer apply and then I’d be in even more trouble. I waited, hovering in the doorway between the kitchen and the living room, acid churning up my throat, holding a handful of forks.

Mom’s back was to me and her shoulders had risen, a sure sign of tension. She hung up the phone and dialed someone else without turning around. “Shirley? It’s Brenda. Is Paul at your house, by any chance? Yes, I heard about Richie and Jake. Melissa just told me, but it was kind of garbled. She was upset, obviously. But you haven’t seen Paul? Oh, he’s probably riding his bike around somewhere and lost track of time. If you see him, tell him to come home, would you?”

I stood there, watched her shoulders rise higher and higher as she hung up and dialed someone else and had the same conversation again, and then again and again. Her shoulders were practically touching her earlobes.

I don’t know how many calls she had made when someone knocked at the front door. Mom quickly disentangled herself from the phone cord, which she’d slowly wrapped around her hand, and answered the door.

She seemed to not even be aware of my presence by then, her mind out somewhere her body couldn’t be, roaming around looking for Paul. I followed her into the hallway, staying a few feet back, still gripping the forks. Later I’d find a bruise striped across my palm. It didn’t go away for a long time.

There was a police officer on the other side of the door, and for a moment I saw Mom’s shoulders drop in relief. Even if Paul had been naughty, had been caught acting out, her body language seemed to say, at least he was safe in the back of the squad car.

Then he spoke, and he said that Paul had been with Richie and Jake in the McIntyre place. He said that Jake’s parents had tried to contact us earlier by phone from the hospital. I thought of the ringing phone, and bile rose in my throat.

He said that Richie and Jake were badly hurt, and still upset, but they seemed to think Paul had died inside the house. Mom’s shoulders slumped then, slumped lower than I’d thought possible, like all the bones had liquefied inside her body, and she sagged against the door.

The police officer looked apologetic, and said, “I’m sorry, ma’am. We searched the house and there was no sign of your son.”

Mom straightened a little. “So, he might be all right, after all.”

“Um,” he said, and I noticed, from a faraway place, that he seemed very young. We knew all the police officers that patrolled this neighborhood, but I didn’t know his name. “I need to show you something. I’m sorry. Can you tell me if this belonged to your child?”

He held something up, and I walked a little closer to see what it was. There was a patch of blue inside a clear plastic bag, a patch of blue covered in blood that looked exactly like the sleeve of Paul’s favorite Cubs shirt, the one he’d been wearing when he left the house that day. The sleeve had been in Richie’s hand when he came out of the McIntyre place, because he’d tried to save my baby brother. He and Jake had both tried to save him, but Paul had slipped away.

TWO

THE ADULTS IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD didn’t believe Richie and Jake’s story about the house eating Paul. I mean, how could they? Two hysterical blood-covered kids talking about a monster that came out of the closet upstairs—who would believe that? They thought it much more likely some itinerant serial killer (or, in Ted Dobrowski’s words, “a psycho bum”) had kidnapped and killed my little brother.

There were bloodstains on the floorboards near the place where Paul disappeared, which seemed to give credence to this theory. Explaining Jake’s missing arm, though—that took some doing. Jake’s parents said that the attacker carried an axe and had chopped his arm off in a killing frenzy. This didn’t account for the fact that the arm was gone—poof—into the ether. Surely, if Jake’s arm had been chopped off, it would still be in the house.

People around the neighborhood started saying the killer had taken the arm away along with Paul.

“Some kind of sick trophy,” I hear Tanya Ruffio telling Mary Siderias in Jewel. They had their shopping carts pushed together near the end of the baking aisle, and as my mother rounded from the pasta aisle, they jumped apart guiltily. Mom just nodded at them and continued on in the direction of the flour.

Mary opened her mouth like she was going to say something, but Tanya nudged her, and they both pushed their carts out of the aisle. I trailed after my mom, my feet shuffling along the shiny floor. She never let me out of her sight if she could help it for the rest of that summer. Sometimes, when I was half asleep, I’d hear her come to my bedroom and just stand there for a few minutes. I never knew if she was watching over me or just checking to make sure I hadn’t sneaked out of the house.

The Incident at Jewel was maybe a week or so after Paul disappeared, and about two weeks before my father tried to burn down the McIntyre place.

Dad was inconsolable with Paul gone. He’d wanted a son more than anything. I was an okay substitute for a few years, but nothing more than that. When I was little, he’d never let my mom put me in a dress and pigtails unless it was a special occasion. He taught me how to catch a baseball and how to run with a football. He bought me boys’ sneakers and boys’ corduroys, and my mother clucked her tongue when I came in from outside covered in mud, carefully cradling a salamander or an earthworm. I was my dad’s favorite person, his shining star.

Then Paul was born, and suddenly I wasn’t the center of the universe, just some distant planet orbiting in the coldest reaches of the solar system. My skinned knees and dirty fingernails weren’t cute anymore. I was five years old and constantly admonished to “act like a lady.” Mom bought me pink sneakers and I immediately took them outside and coated them in dirt, furious and ashamed.

As soon as Paul was old enough to do more than wobble and drool, Dad attached his son, his beloved baby boy, to his hip and never let him go. It was always “Wanna go for a ride with me, bud?” or “Wanna toss a ball around for a while, champ?” It was inevitable that Dad would crack wide open when Paul was lost, just like the hole in the world that roared inside the old McIntyre house. Me and Mom could never be enough to hold Dad together.

People were kind. Of course they were kind, especially at first. They all got out and searched the neighborhood for Paul, even though Jake and Richie told their parents and the police over and over that Paul had been eaten by the house and nobody was going to find him anywhere. When the police and their parents and every other bewildered adult asked them to explain, they just kept saying that there was a monster in the closet. But who would believe a monster in the closet, especially at their age? They weren’t really little kids, after all.

Ted Dobrowski asked Mom for a picture of Paul, and she gave him Paul’s third-grade school photo, the one where he had a crooked half-smile and a hanging baby tooth instead of an adult incisor. Ted took the picture to a place with a copy machine and made up “HAVE YOU SEEN THIS BOY?” flyers and handed them out to everyone. They were stapled on every telephone pole in a twenty-block radius. They were attached to corkboards at the YMCA and at the senior center and at all the churches. But this didn’t matter, because Paul had been eaten by the house and nobody was going see him ever again.

Neighbors brought potato nugget casseroles and tuna noodle casseroles and ground beef lasagnas in disposable aluminum pans wrapped with foil on top, the freezing and reheating directions written in black marker. As they handed the pans to my mother, they said things like, “Don’t worry, we’ll find him” and “We’re keeping you in our prayers.” But no matter how many casseroles they passed through the door or how many prayers they claimed to say, a miracle never happened, and Paul was never found.

Dad couldn’t begin to grasp the concept of his life without Paul. He wandered through the house like a shade, never responding to anyone, his eyes blank and staring. When Mom called him to the dinner table, he’d look at the scoop of potato nugget casserole or tuna noodle casserole or ground beef lasagna on his plate and push it around with his fork, but he seemed incapable of lifting a bite of food to his mouth. Mom would say, “Frank, you should eat something,” but he’d just keep rearranging the food until it didn’t resemble food at all, and then he’d get up and scrape it into the trash can.

He started smoking again, a habit he’d quit in order to get Mom to marry him. Within a few days of Paul’s disappearance, he was as dry and combustible as tinder in a drought. In a way, it wasn’t a surprise when he burned like tinder, too.

* * *

IT STARTED THE same way it had started with Paul. We’d lost track of my brother, and then we lost track of my father. Mom was lying down in the bedroom with the curtains closed and a dark cloth over her eyes. I was in my bedroom with my headphones on (U2 this time; I was never able to listen to a Black Crowes song again without feeling sick). My upper body was hanging out of my bedroom window, and I was smoking one of Dad’s cigarettes. Nobody noticed if I smelled like cigarette smoke anymore, not with the haze of Dad’s renewed habit lingering in every room no matter how many windows Mom opened.

Even though Mom felt the need to check on my presence fifteen hundred times a day, it didn’t seem like she was paying attention in any meaningful way. All of her energy went into keeping Dad going, winding him up like an automaton every morning. She couldn’t spare an actual thought for me while her husband was disintegrating before her eyes.

I didn’t mind, not really. A deep, shameful part of me was terrified that Mom and Dad would find out I’d dared Paul to go into the house. If they found out it was my fault that Paul was gone (no one in my household would admit he was dead, or even entertain the possibility)—well, I was sure they’d kick me out, disown me. I was nothing but a burden anyway—a troublemaker who picked fights at school and didn’t turn in my homework and cut class whenever I felt like it. Paul had been the good child—Mom’s little angel, Dad’s darling boy. What did they care if I smoked? What did I care if they didn’t pay attention to me?

I finished my cigarette, stubbed it out on the underside of the sill, then carefully wrapped it in a tissue and put it at the bottom of my trash can. There was no reason to invite Mom to ground me for an even longer period.

My bedroom faced the backyard. There was a big catalpa back there, and Dad always threatened to cut it down because he hated cleaning up the giant seed pods that dropped from it every year. He used to give Paul two dollars to clean up the pods once a week.

There was also a small aboveground pool, maybe ten feet across and only four feet high. It barely fit—we had a city yard, which basically meant a postage stamp–sized patch of grass—but the pool made both me and Paul popular with the other kids in the neighborhood in the summer. It was nice to have somewhere to cool off that wasn’t a crowded park district pool or Lake Michigan, which stayed dead freezing until mid-August. Dad had a small shed of tools and other junk, and between the pool and the tree and the shed there was just enough room to walk.

Our yard was surrounded by a high wooden fence and bordered on two sides by other yards and by an alley in the back. From my vantage I could see the Walkers’ yard to our right. The Walkers already had six kids, and Mrs. Walker was pregnant with their seventh. There was a mess of bikes, balls, racquets, bats, and other toys scattered over the browning, nearly knee-high grass.

On the opposite side of our yard was a neat, well-tended garden full of tomatoes and zucchini and Swiss chard and peppers. Mr. Labriola was a sixty-something widower who lived to share vegetables with his neighbors, whether those neighbors wanted the vegetables or not. There was only so much zucchini I could tolerate.

Our three buildings were unusual on the block because in each case they were owned by only one family, whereas most of the others housed at least two, if not three. I’m not sure how the Walkers would have fit on one floor, to be honest.

I sat in the window for a while longer before closing the screen again. Dad must have gone out to the shed right after that. If I had seen him, or if he had seen me, would it have changed things?

I thought he was downstairs watching TV. The volume was turned up so loud that I heard it through my closed door and my headphones. I flopped on my bed, tried not to think of my little brother saying, “Don’t call me Paulie,” failed, and decided to get some potato chips from downstairs. My parents’ bedroom door was closed, so I assumed Mom was still in there, asleep.

The television noise was significantly louder when I reached the top of the stairs. I stopped the tape in my Walkman, irritated. Who could hear Bono over the sound of The Price Is Right blaring through the house?

When I reached the bottom of the stairs, I stuck my head in the living room doorway. Sometimes Dad fell asleep on the couch with the TV turned up. He wasn’t in the living room, though. I frowned, found the remote under a brown corduroy throw pillow, and turned the volume down.

Then I checked to see if he was in the dining room, reading the newspaper at the table. He used to do that before Paul disappeared. But he wasn’t there. He wasn’t in the kitchen, either.

I turned on the light for the basement stairwell and called, “Dad?” down the stairs, but the fact that I had to turn on the light in the first place should have been a clue that the basement was empty.

I peeked out the front to see if maybe he’d gone for a drive, but his brown 1989 Chevrolet Caprice was still parked at the curb. Dad staunchly refused to update to a smaller car, which would have been more practical in the city. His car made all the little Mazdas and Hondas look like lifeboats next to the Titanic.

He must have gone for a walk, I thought, but my stomach churned. I didn’t know why, but something felt wrong—really wrong. I went to the back door and pushed open the screen, stepping out. There was Dad’s grill to the left, crammed in the space between the house and pool. There was the pool, leaves and bugs floating in the water. Nobody had bothered to skim it in days. Everything seemed normal, and there was no sign of my father.

That’s when I noticed the shed was open. Relief washed over me. He must be getting ready to mow the front lawn. I was glad, not because the tiny square of grass in front of our house really needed mowing, but because it was a normal Dad thing to do. It meant he wasn’t brooding over Paul.

I stood there for a few minutes, waiting for him to push the mower out into the sunshine. Nothing happened. The open shed door seemed more like a watching eye than a comforting sign of normalcy. The sick feeling in my stomach returned. I tilted my head, listening. If Dad was in the shed, he wasn’t making any noise. I ran across the lawn, barefoot.

Halfway there I stepped on a honeybee busily harvesting from a clover flower. The stinger slid into my skin and I howled, hopping on one leg.

“Shit, shit, shit!”

I felt the sting swelling in the arch of my foot. This usually happened to me several times per summer because I hated wearing sandals or flip-flops. After a second the pain subsided and I limped toward the shed, although I was sure that he wasn’t in there. He’d never have stood by and let me curse like that without a reprimand.

I squinted into the shed, bright yellow spots lingering in my gaze from the sun. Dad wasn’t present, but I scanned all around, trying to get a sense of what he’d been doing.

Everything looked in order. Dad was compulsively, methodically neat. The mower was in one corner under a waxed canvas cover. Trimming shears and two different types of rakes hung on the wall. Three shelves contained potting soil, small pots, gardening gloves (Mom liked to plant flowers and herbs in the front yard). A bag of mulch stood in the opposite corner from the mower.

Wait, there’s something missing. My eyes ran over the room again as I tried to figure it out. Mower, check. Rakes, check. Gardening shit, check check check. I couldn’t figure it out for a few moments. Then I realized that the red fuel can that normally stood next to the mulch was gone.

Why would Dad take that out?

Maybe he wanted to mow the front lawn and realized the mower was out of gas, I reasoned. But if that was the case, why hadn’t he just taken the car? The nearest gas station was more than a mile away, and he wouldn’t want to make the walk in the heat, especially carrying a heavy can full of liquid.

Something bad is going to happen, I thought.

I ran back inside, found my dirty orange Converse sneakers by the front door, and pulled them on, tucking the laces under the tongue instead of bothering to tie them.

Something bad is happening. This thought had more urgency than the first, and my conviction that some irreparable harm was in process hardened.

There was only one place Dad could be, only one place that could yank him toward it mouth-hooked like a fish.

It was five lots away from ours. The front fence seemed so far away from me, a blur in the distance. The peeling paint of the siding, the cracked and boarded windows, the waist-high weeds all around that hid the broken bottles and used condoms and cigarette butts left behind—all this I could see, but not my father.

The flapping rubber soles of my shoes smacked on the sidewalk. I could hear my own breath, shallow and ragged, and sweat ran down the small of my back. There was something wrong and I knew it, something so wrong, and if I hurried, I could stop it, but I had to be fast enough.

“Frank? Just what the hell are you doing?” The words drifted to me from someplace far away, because my blood was roaring in my ears.

I became vaguely aware of other figures moving in my vision, and I slowed to a halt in front of the house next to the McIntyre place.

Mr. Riley had dropped the water hose on his lawn and was crossing the street. Mrs. Riley stood on her porch, holding on to the ends of her cardigan, her mouth pinched tight.

Ted Dobrowski opened his door. He held an Old Style, wore his Sandberg jersey.

It was exactly the scene that Mrs. Riley described to me later, the way everything had been the day Paul died. Only this time Dad was in the picture instead of two screaming, blood-covered boys. And Dad was pouring gasoline around the house, splashing it against the crime scene tape that covered the front door.

“Frank, what the hell are you doing?” Carl Riley said again, and the metal gate in front of the McIntyre place screamed as Carl pushed it open.

Dad didn’t say anything, just placed the gas can down on the porch as Carl Riley approached him. I didn’t want to get any closer, but my sneakers slid along the ground of their own accord. Every part of me trembled—in fear, in guilt—and the house throbbed with menace, radiated a malevolent miasma that hadn’t been there before Paul and Richie and Jake had gone inside.

That miasma tickled my nose, seeped in between the pressed seam of my lips, dived into my lungs, and tried to stop my breath.

“Jessie!” someone said, someone who sounded for a second like my mom, but it wasn’t my mom. It was Mrs. Riley, grabbing my arm, pulling me back toward the street, away from my father, my wild-eyed father.

I stumbled as we reached the curb and yanked my arm out of her grip. “Leave me alone.”

“Jessie, come on. Get away from here.” Her voice was pleading. “Hasn’t your mother been through enough? She wouldn’t want you to get hurt.”

I wasn’t so sure about that. I thought that if my mom had been given a choice, she’d gladly have sent me into that house if it meant she could have Paul back.

“Jessie, please,” Mrs. Riley said, plucking at the sleeve of my T-shirt.

I pulled my arm away from her again, and shook my head no. “I’m not leaving.”

She made a little despairing sound, and opened her mouth to argue, but I cut her off. “He’s my dad, and I have as much right to be here as anyone.”

Part of me thought I should go back home, get Mom. She might be the only person in the world who could stop Dad from doing what he was doing. Another part of me thought that no one could stop Dad except Paul. If Paul had appeared at that moment, had walked out of the McIntyre place . . . well, Dad would have given anything for that to happen. But it wasn’t going to happen, so Dad kept splashing gasoline around the house.

Carl Riley pled with him in an undertone. I heard words like “dangerous” and “burn down the whole neighborhood.” Dad just stared at him, his face set and determined, and that expression reminded me so much of Paul’s on the last day I saw him that I almost cried out.

No, I should have said. No, don’t do it. It’s my fault Paul is gone. I’m sorry. Stay.

I should have said, Dad, please come home.

Maybe he wouldn’t have heard me. Maybe he wouldn’t have cared. I should have tried. Another mistake in a life that’s been full of them, another regret to toss on the pile.

But I was paralyzed—by my grief, by my guilt, by the expression on my father’s face that looked so like my little brother’s.

“I’m calling the police.” Alice Majewski’s voice came wavering across the street, thin but determined. “Frank, you’d better stop right now or I’m calling the police.”

I felt Sheila Riley shift, sensed rather than saw her shake her head at Alice. I’m sure Mrs. Riley thought her husband would succeed in talking Dad down from the ledge. None of us realized Dad had stepped off the ledge already and was falling somewhere we couldn’t follow.

Dad abruptly turned away from Carl Riley and strode to the corner of the McIntyre house. His blue Bic lighter was in his right hand as he crouched down and flicked the flame toward the gasoline splashed there.

Sheila Riley sucked in her breath and Carl yelled, “Frank, don’t!” but I just stood there, my heartbeat so loud I thought the organ was about to burst from my chest. We all expected the dramatic whoosh