Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Richard Hill and Ernest L. Rossi's The Practitioner's Guide to Mirroring Hands: A Client-Responsive Therapy that Facilitates Natural Problem-Solving and Mind Body Healing describes in detail how Mirroring Hands is conducted, and explores the framework of knowledge and understanding that surrounds and supports its therapeutic process. Foreword by Jeffrey K. Zeig, Ph.D. In this instructive and illuminating manual, Hill and Rossi show you how Mirroring Hands enables clients to unlock their problem-solving and mind body healing capacities to arrive at a resolution in a way that many other therapies might not. The authors offer expert guidance as to its client-responsive applications and differentiate seven variations of the technique in order to give the practitioner confidence and comfort in their ability to work within and around the possibilities presented while in session. Furthermore, Hill and Rossi punctuate their description of how Mirroring Hands is conducted with a range of illustrative casebook examples and stage-by-stage snapshots of the therapy in action: providing scripted language prompts and images of a client's hand movement that demonstrate the processes behind the technique as it takes the client from disruption into the therapeutic; and from there to integration, resolution, and a state of well-being. This book begins by tracing the emergence of the Mirroring Hands approach from its origins in Rossi's studies and experiences with Milton H. Erickson and by presenting a transcription of an insightful discussion between Rossi and Hill as they challenge some of the established ways in which we approach psychotherapy, health, and well-being. Building upon this exchange of ideas, the authors define and demystify the nature of complex, non-linear systems and skillfully unpack the three key elements of induction to therapeutic consciousness focused attention, curiosity, and nascent confidence in a section dedicated to preparing the client for therapy. Hill and Rossi supply guidance for the therapist through explanation of therapeutic dialogue's non-directive language principles, and through exploration of the four-stage cycle that facilitates the client's capacity to access their natural problem-solving and mind body healing. The advocate Mirroring Hands as not only a therapeutic technique, but also for all practitioners engaged in solution-focused therapy. Through its enquiry into the vital elements of client-cue observation, symptom-scaling, and rapport-building inherent in the therapist/client relationship, this book shares great wisdom and insight that will help the practitioner become more attuned to their clients' inner worlds and communication patterns. Hill and Rossi draw on a wealth of up-to-date neuroscientific research and academic theory to help bridge the gap between therapy's intended outcomes and its measured neurological effects, and, towards the book's close, also open the door to the study of quantum field theory to inspire the reader's curiosity in this fascinating topic. An ideal progression for those engaged in mindfulness and meditation, this book is the first book on the subject specially written for all mental health practitioners and is suitable for students of counseling, psychotherapy, psychology, and hypnotherapy, as well as anyone in professional practice.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 593

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands

Picasso once remarked that “art is the elimination of the unnecessary.” Ernest L. Rossi’s Mirroring Hands method is brilliant in its simplicity and elimination of the unnecessary, yet is complex beyond belief in the results it can engender. This method can eliminate any resistance you may encounter in the change process and can evoke deep inner wisdom, often in a very short time.

Richard Hill has facilitated and expanded this guide to using Mirroring Hands in such a way that makes it accessible for all.

Bill O’Hanlon, author of Solution-Oriented Hypnosis and Do One Thing Different

In The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands, Richard Hill and Ernest L. Rossi honor the wisdom of the courageous people who come to us seeking healing. They offer deep wisdom about the inherent health that lies within our clients and the support we can provide to allow that health to come forward. A wonderful contribution!

Bonnie Badenoch, Ph.D., marriage and family therapist, author of Being a Brain-Wise Therapist and The Heart of Trauma

Within the crucible of a technique Hill and Rossi call Mirroring Hands, The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands shares a storehouse of practical insight, scientific theory, and clinical wisdom. In the process they challenge accepted assumptions and synthesize complex principles, all the while encouraging clinicians to learn to listen to their inner voice.

The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands is a warm and fascinating adventure in which you get to know two explorers of the mind and learn about the history of psychotherapy while gaining practical knowledge. You may not agree with everything the authors say, but I suspect that you will respect and enjoy their unique blend of complexity, depth, and self-insight – so often missing from contemporary discussions.

Louis Cozolino, Ph.D., author of The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy, The Neuroscience of Human Relationships, The Making of a Therapist, and Why Therapy Works

What a fascinating book! Starting as an easy read, it gently descends to deep levels. Richard Hill brings straightforward clarity to Ernest L. Rossi’s genius, and their combined work brings contemporary insight into ideas pioneered by my father, Milton H. Erickson.

The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands will inspire ongoing discoveries by others and carry this important work into tomorrow.

Roxanna Erickson-Klein, Ph.D., R.N., author of Hope and Resiliency and Engage the Group, Engage the Brain, editor of The Collected Works of Milton H. Erickson

Have you ever wondered how to help a client access their unconscious? Building on the work of Milton H. Erickson, Ernest L. Rossi developed Mirroring Hands to do just that, and, along with Richard Hill, he has now brought it to you. Not only do Hill and Rossi give clear step-by-step instructions for how to use Mirroring Hands, but they also lay out the framework for understanding the dynamic power of this tool.

The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands is a well-rounded resource full of practical applications and illustrative casebook studies. Readers will find themselves both informed and empowered by this guide.

Ruth Buczynski, Ph.D., licensed psychologist, President, National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine

Providing extensive research background for the theories on which the Mirroring Hands technique is based, The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands is an outstanding manual accomplished with precision and clarity. It takes readers on a journey through neurophysiological and genomic discoveries and offers intriguing speculations on quantum influences which may give readers a glimpse of the inevitable future of psychotherapy.

Stephen Lankton, M.S.W., D.A.H.B., editor-in-chief, American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, author of The Answer Within and Tools of Intention

There is plenty of research and ideas presented here that made me think new thoughts, and you can’t ask much more from a book. I’m sure The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands will be one I return to repeatedly.

Trevor Silvester, Q.C.H.P.A. (Reg), N.C.H. (Fellow), H.P.D., Training Director, The Quest Institute Ltd, author of Cognitive Hypnotherapy, Wordweaving, and The Question is the Answer

The Practitioner’s Guide to Mirroring Hands really does do magnificent credit to Richard Hill’s documentation and to his dedication in uncovering the genius of Rossi and Erickson, and will provide you with a never-ending source of wisdom on your professional journey in the therapy room. The authors should be commended for this text, which obviously sets out to achieve a quite remarkable feat in its presentation of the Mirroring Hands process, and it doesn’t disappoint. It is indeed a tour de force which will – and should – become a classic.

Dr. Tom Barber, founder, Contemporary College of Therapeutic Studies, educator, psychotherapist, coach, and bestselling author

This book honors two extraordinary women: Kathryn Lane Rossi and Susan Jamie Louise Davis who have not only made our lives an immeasurable pleasure, but have also been a source of healing for many thousands of people.

Acknowledgments

This volume spans many decades of growth and change, so acknowledging everyone who has made a contribution is probably impossible. We would like to begin with a heartfelt thank you to all our patients and clients over the years who have been, in a very special way, co-creators in the emergence and development of Mirroring Hands. It almost goes without saying that we equally acknowledge the numinous, and continuing, presence of Milton H. Erickson.

Richard Hill extends the first acknowledgment and his unqualified gratitude to Ernest Rossi, who has facilitated his becoming as a therapist for more than a decade. Starting a new career in midlife is so much more possible when surrounded by the best.

We must, again, thank our wives, Kathryn Rossi and Susan Davis, for their enormous contribution, on both professional and personal levels. Almost as dedicated has been Michael Hoyt, in San Francisco, who has generously read and re-read progressive drafts, providing invaluable guidance and advice. Many thanks to Nick Kuys, from Tasmania, Australia, for his kindly role play as our “quintessential practitioner,” helping us to appreciate what was interesting and important. A very special thanks to Jeff Zeig for contributing the foreword. He is an icon of professional excellence throughout the world and tireless in his work as founder and board member of the Milton H. Erickson Foundation.

We have been befriended and gently encouraged by wonderful people, including John Arden, Bonnie Badenoch, Rubin Battino, Steve Carey, Giovanna Cilia, Lou Cozolino, Mauro Cozzolino, Matthew Dahlitz, Jan Dyba, Roxanna Erickson-Klein, John Falcon, Bruce and Brigitta Gregory, Salvatore Iannotti, Paul Lange, Stephen Lankton, Paul Leslie, Scott Miller, Michael Munion, Carmen Nicotra, Bill O’Hanlon, Kirk Olson, Debra Pearce-McCall, Susan Sandy, Dan Siegel, Lawrence Sugarman, Reid Wilson, Michael and Diane Yapko, and Shane Warren. There are more we hold dear to our hearts, including colleagues and friends at the Global Association for Interpersonal Neurobiology Studies (GAINS) who are more family than just friends; the wonderful people at the Milton H. Erickson Foundation; and Venkat Pulla and our Strengths Based Practice Social Work community in Australia, Asia, and the Subcontinent. It has been a wonderful journey. Thank you all.

Our appreciation goes to the whole team at Crown House Publishing who have believed in the value of this book and done so much to make it possible. Thanks to Mark Tracten for being an annual presence for many years, David and Karen Bowman, Tom Fitton, Rosalie Williams, and all the hard-working Crown House team around the globe.

Contents

Foreword

Ernest Rossi has been a seminal contributor to and a historical figure in the evolution of psychotherapy. He is blessed to have Richard Hill as a collaborator.

Rossi has contributed in many professional arenas, including advancing Jungian perspectives and the work of Milton H. Erickson, M.D., who was the dean of 20th century medical hypnosis. Rossi was Erickson’s Boswell and the person who was primary in making Erickson’s work available to the world. But Rossi’s own groundbreaking contributions have been in psycho-neuro-biology. He pioneered the use of hypnotic techniques in mind–body therapy, including the way in which hypnotic suggestion alters gene expression. How the mind creates the brain and the body is a door that Rossi has unlocked so that other investigators can enter and explore.

Contributions to hypnosis have also been central to Rossi’s work. He is a specialist in ideodynamic activity – the way in which associations and mental representations alter behavior and sensory experience. When you think vividly about a lemon, you salivate. If you’re a passenger in a car, and you want it to stop quickly, you stomp on the imaginary brake. These ideodynamic principles can guide psychotherapy and are the foundation of this important book.

Rossi invented the Mirroring Hands technique, which can be used both for hypnotic induction and hypnotherapy. The protocol and accompanying theory are presented and enriched with clear clinical examples. Variations are explained and limitations are offered. Therapists who want to advance their technique can now learn from a psychotherapeutic master.

Richard Hill is a co-author, not merely an expositor. He expounds on the importance of curiosity as a palliative factor and enriches perspectives on using the brain to alter the body. Orientations are developed to aid clinicians to avoid burnout.

Not only is this book an important resource for those who practice hypnosis, it can also be an important introduction for any psychotherapist who wants to learn about mind–body therapy. This manual provides keys to the solutions to problems that have previously evaded psychotherapeutic technique.

Ernest Rossi and Richard Hill are to be commended for their vibrant exposition. They have cleared previous undergrowth and created a path that others will be wise to follow.

Jeffrey K. Zeig, Ph.D. Milton H. Erickson Foundation

Introduction

Richard Hill Meets Ernest Rossi

I first saw Ernest Rossi demonstrate Mirroring Hands in December 2005. My reaction to Dr. Rossi’s undeniable intellect and broad ranging ideas was to be, simply, blown away. I knew this was a turning point, a phase shift, in my life. There had to be a reason why I had flown 7,500 miles to attend the Evolution of Psychotherapy conference. I did not ever imagine I was embarking on a journey that would lead to a decade long engagement with Ernest Rossi, culminating in this book.

But things happen, and they have a way of telling you what you need to know. Sometimes you notice quickly and easily, other times you need to be smacked in the face more than once before it all falls into place. So, what were the smacks in my face? Frankly, there have been quite a few over the past decade. Let me share an experience from a few years ago which absolutely convinced me why I was so drawn to Mirroring Hands. I hope that in describing a case, you can more easily “walk in my shoes” for a while.

RH’s Casebook: A “Walk-In”

I answered an unexpected knock on the door of my clinic. A woman in her mid to late thirties asked if I could see her straight away. That is a little unusual but, as it happened, I was available and I invited her in. She spoke quickly and had a way of gazing intently that was a little unnerving, but I didn’t feel she was psychotic, just intense. In something of a machine-gun delivery she set up the conditions for the session.

Your sign says counseling and brain training. I don’t know what brain training is. (She didn’t pause for an explanation.) I’ve just come from seeing another psychiatrist. In fact, I’ve seen a lot of different therapists, had just about every therapy … and read everything. You reckon you can do something different? I’ll give you 60 minutes.

Well, it was nothing if not a challenge, and so we began. She sat down and I went through my standard intake process. She wasn’t all that keen on telling her story in detail, again, to another therapist.

Then she looked at her watch:

You have 45 minutes left.

No pressure! In the tradition of Milton H. Erickson, I was looking for her to show me some clues as to how to proceed.1 She had been clear so far: don’t do any of the standard treatments. She almost seemed to be saying, don’t treat me at all. Wow! This was such a unique experience and, to be honest, I really didn’t know what to do. So I watched her. She was very expressive with her hands, pushing them toward me to highlight things as she spoke. I was suddenly transported to my workshops with Ernest Rossi. This looked something like what happens during a Mirroring Hands experience. I took the gamble that no other therapist had used this technique with her.

I’m noticing that you are very expressive with your hands. Have you ever really looked at your hands … noticed what is really interesting about them?

She was surprisingly cooperative and stared at her hands for about 30 seconds, then flicked her gaze back to me.

What are you doing?

Well, she had basically told me that she didn’t think much of what therapists thought. She was also sick and tired of them forcing different therapies down her throat. Feigning a surprised confusion, I replied:

I don’t know, but you said you’d done everything. So … have you ever done anything like this before?

She stared intently at me for a moment, looked at her watch and told me as a matter of fact:

You have 35 minutes.

I began to facilitate Mirroring Hands. We will learn the details of the procedure later in the book, but, suffice it to say, as the experience unfolded, she told me, with some surprise, that she felt her hands were representing two aspects of her persona. One hand was representing a part of herself she keeps private and the other hand was representing her public face. It was like watching someone open doors to rooms she had not seen for a long time. Sometimes she shared what was happening and other times she just explored her “rooms” privately. Many things happened over the next 30 minutes that are not vital to replay here, but finally her hands settled together, with her “public self ” hand totally covering her “private self ” hand.

She was quiet for a little while, then looked up. Her eyes had softened their intense gaze. Her voice was slower and more contemplative. It was clear that she knew something now that she did not know 30 minutes ago. Over the next 15 minutes – yes, she stayed beyond her 60 minute deadline – she told me how she had created this “public self ” as a protector against early family difficulties. Now she knew why she felt so frustrated and had resisted previous therapy. Everyone was trying to “fix” her public face, but that was her protector. To take away her protector would be disastrous for her private self.

After all those years of therapy, when she had only allowed people to see her protector self, today she had allowed her hands to become mirrors into her deeper self. In this Mirroring Hands experience she was able explore “rooms” that were usually locked or avoided. She was able to tend to her vulnerable “private” self and begin the process of letting her protective “guardian” self take a well-earned rest. The most amazing thing is that she did the bulk of this work without my interference, imposition, or direction. She found what she was searching for: how to begin her own healing. I expect she might say that was 60 minutes that truly changed her life. Equally, that was 60 minutes that truly set my sails.

What Is This Book About?

We will show how to create and facilitate therapeutic experiences like this, utilizing the Mirroring Hands technique. We will also show how to integrate our therapeutic approach across all therapies, and even into daily life. The woman found natural “inner” and “between” connections on numerous levels that literally changed her psycho-neuro-biology. The realizations and changes that happened to her indicate a variety of implicit activities, including brain plasticity and neural integrations, cognitive perceptions entering and altering conscious awareness, the necessary gene expression and protein synthesis to enable these processes, and the possibility of epigenetic changes to her DNA.2 On the observable level, she clearly experienced new thoughts and a deeper self-understanding. It was evident that she had connected with her own capacities for problem-solving and was ready to begin her own healing. We will describe and show how Mirroring Hands is conducted, but equally, if not more importantly, we will explore the framework of knowledge and understanding that surrounds and supports the process. We have differentiated seven variations of Mirroring Hands. These are punctuated with chapters that reveal different aspects of the surrounding and supporting framework. The complete picture gradually emerges over the course of the book as we guide you around the activities of the technique and into the foundational frameworks of the Mirroring Hands approach.

When, Where, and Why?

It is important to clarify at the very beginning that we are not presenting Mirroring Hands as the therapy for everything and everyone. It is not a magic bullet, any more than is any other therapy. In fact, current research is concluding that no one therapy is necessarily more effective than any other.3 As if to confuse and confound, practitioners know from their personal cases that a particular therapy can be much more successful with a particular client. Equally, with another client, a different therapy is more effective. The conundrum is resolved when we position the client as central to the therapeutic process, when the experience and efficacy of the therapist and the therapies they utilize are taken into account, and when there is a comfortable and collaborative relationship between the therapist and the client (the therapeutic alliance).4 A pragmatic definition of evidence based practice has created a pressure toward determining preferable therapies or perhaps permissible therapies that should be applied to clients only by available, research based evidence. This appears to be a growing construct in agencies, insurance funded therapies and other funded institutions, as well as many educational institutions. Although we appreciate the responsibility to produce predictably successful outcomes, we feel that these limiting determinations are not the right path to follow.

You may be surprised that the American Psychological Association’s Presidential Task Force produced and published a formal definition in 2006 that is not evidence centric: “Evidence-based practice in psychology (EBPP) is the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences.”5 It is quite clear that the client is the context, and the therapy, intervention, or technique utilized is only one part of an integration of reliable practice, practitioner expertise, and how the client responds. A client centered approach is hardly new. It was first introduced by Carl Rogers in the latter half of the 20th century.6 We suggest that it is possible to create an even deeper degree of engagement with the client in their pursuit of effective therapy by asking the therapist to take one more step back from the client once they are “centered,” and allow the therapy to emerge in a client-responsive way. So, the answer to when, where, and why is much more about the client than it is about prescribed or usual treatment and predetermined therapeutic programs or plans. Again, it is important to qualify this by acknowledging that there are times when a therapist needs to do much of the work and perhaps impose a therapeutic program on a particular client. On close examination, however, even those situations can be seen as client-responsive because the client is showing they need help to get to a place where they can start to work for themselves.

Mirroring Hands is introduced at the best time, in the best place, and with the best intention – when, where, and why – in response to the client’s indications of need. We suggest this is possible for all therapy because the best therapy emerges from the interaction between the client and the therapist.7 It is, therefore, not our desire to predetermine the conditions in which you should utilize Mirroring Hands, but, having said that, we would like to give some guidance based on our experience.

When You Just Don’t Know

Mirroring Hands is often utilized to break through the impasse of the client’s “I don’t know” or even “We don’t know,” when both client and therapist are unsure. You saw this dual “not knowing” in the case at the beginning of this introduction. Admittedly, this is why people come to therapy – because they don’t know what to do or they don’t know what their problem is really all about. Sometimes clients talk of a feeling that they know there is something to know, but that knowledge just can’t be reached or there is something blocking access to it.

Regardless of the techniques or processes that emerge during a session, the first task is always to create and build the therapeutic alliance.8 This often starts with talking things through. This is a very familiar beginning for most therapists. This conversation largely comes from explicit awareness, where both client and therapist can verbalize or, in some other way, consciously express what they are thinking or feeling. Establishing and building an interpersonal rapport is essential to earn the trust of the client and for the client to feel safe. From trust and safety, it is possible to deal with the issue that has moved the client to come for therapy.

Beneath conscious control there is an inner, implicit world which does not have direct access to vocalization or consciously directed behavior. It is hidden, elusive, and abstract. Memories and feeling that are too difficult to bear are often “purposefully” hidden in the implicit, inner world. Behaviors and emotions can appear on the surface almost as if arising from somewhere unknown. These are usually called symptoms, but, equally, they are how the implicit makes itself known in the explicit. Symptoms create feelings of disconnection and disintegration, creating a disharmony that triggers a client to seek therapy. Mirroring Hands is a natural and responsive way to enable the client to repair those connections. We will show how this can be done safely and with natural comfort, even when the therapeutic experience is difficult and testing.

Exactly how therapy proceeds depends on what the client is able to do, is expecting to do, and is prepared to do. It can also depend on what the client knows about you and your practice. Clients who have come specifically for Mirroring Hands might want to start with that process almost straight away. That doesn’t mean that we always do. We still work carefully with all the messages coming from the client. We discuss this sensitivity of the therapist to the client’s many levels of communication in Chapter 7 (Natural, Comfortable, and Sensitive Observation).

Although we describe a number of variations, Mirroring Hands can be utilized in countless ways. The interplay between client and therapist creates whatever is needed in that moment. We discuss this in Chapter 12 (Improvising, Drama, and Mirroring Hands). Improvising is, fundamentally, the unplanned utilization of your knowledge base and skill set. The exact therapeutic experience that emerges is the hallmark of the artisan nature of psychotherapy.9 Think of a pianist who shifts away from the predetermined melody and begins to improvise. The musical notes that emerge are qualities from the musician’s skills, experience, and expertise, as well as the interplay with other musicians, the audience, and the marvels of the player’s own imagination. A poorly educated, technically weak, or inexperienced player is simply not able to improvise as well. This is a capacity that develops over time. Because we want each therapist to add their own unique qualities to their Mirroring Hands experience, we strongly encourage and highlight the importance of learning all that interests you. We really want you to be interested. We also encourage you to seek feedback about your work through regular supervision, and regularly ask your client what is working well for them.10 We will explore different ways that you can receive client feedback, and check on therapeutic effectiveness, as we work through the variations and some of our case examples. We hope this brings you, as a practitioner, confidence and comfort in your ability to flow within and around all your possibilities. Surely that is why the client has sought to bring you into their experience!

Where Do We Begin?

It is not unusual to begin a book with a historical reflection and evaluation. In that tradition, our first chapter explores the history of mirroring hands and how the approach emerged from psychotherapy, therapeutic hypnosis, and Ernest Rossi’s years with Milton H. Erickson. It is unusual, however, to have access to a central player in that history. Chapter 1 (The History of Mirroring Hands) reproduces an interview, a conversation really, between Ernest Rossi and Richard Hill. You will find that the conversation introduces information that has never been revealed before, and also challenges some of the established ways in which psychotherapy is approached, and our personal approach to health and well-being.

That conversation sets up the first challenge which is addressed in Chapter 2 (Thinking IN the Systems of Life). We begin our exploration with a fresh look at how we think. We have an educational tradition of logic based around the principle of cause and effect, but the reality of the world in which we live is somewhat different. This chapter explores the wonders and seemingly mysterious processes that occur in systems, complexity, and chaos. Complexity theory is, simply, a way of explaining what happens when many things make connections, interact, integrate, and produce outcomes. At any given moment, most of us can see that we are involved and engaged with all kinds of influences and it is hard to know exactly what is going to happen. It would be great if things were as simple as one cause and one predictable outcome, but our life experience tells us it is more unpredictable than that.

The very latest brain research occurring as part of the Brain Initiative, launched by President Obama in 2013 in the United States, is shifting research focus from individual brain components and processing mechanisms to looking at the brain as a complex system that shifts and changes as a function of energy and information flow.11 As you work through the book, you will see we also seek to create a shift away from the way we have been taught to think. Rather than being the therapist who sits with but outside the client, introducing interventions that will produce a resolution, we will show you how it is possible to be a therapist who enters into a therapeutic system with the client. We will show how being in the system (instead of acting on the system) produces a very different engagement with the client. The therapist naturally becomes client-responsive, and the client is able to shift from following the therapist to being in the center of the therapeutic process. The client becomes the source of their own therapeutic change.12

A Framework for All Therapies?

Although we are committed to concepts and principles that are well founded in science, each of the theoretical chapters is not delivered as dry academic theory. These chapters describe and explore what is natural to the practice of all psychotherapy. We hope you will find that you can apply the framework and foundations we set out here for Mirroring Hands to everything you practice, both professionally and in your daily life. These chapters establish how systems function, how they self-organize, and how we can – as practitioners, clients, or private individuals – be comfortable and creative participants in the experience. We are trying to shift thinking away from being the conscious controller or the dominating influence, to embracing a state of participation in the natural qualities of our being that do not need control or domination. Instead, we can participate in a creative integration of our whole system. Our argument is that this very control and domination of the experience can make therapy less effective and harder for both practitioner and client.13 Again, it is important to qualify that we are well aware that sometimes it may be necessary to be pragmatic, controlling, and even dominant, but this is rarely being done as a therapy. This is, most often, to stabilize the client or their situation before therapy can begin.

This book is largely addressing situations that are receptive to therapy. Having said that, you will be able to apply the knowledge about our natural rhythms and cycles to the most difficult of cases. You may discover wider applications when we explore the deeper elements of curiosity, what turns it on and what might be turning it off, in Chapter 9 (Curiosity and the Elephant in the Room). Chapter 5 (The Rhythms and Cycles of Life in Therapy) will explain what we mean by natural rhythms and cycles. We believe this puts the practice of psychotherapy in the context of what is natural about us, about the way the world functions around us, and the ways in which we function in the world.

Is There More?

The final two chapters might be considered more like an addendum or appendix, but we feel that we have not finished our guided tour yet. Anyone who has participated in Mirroring Hands has had the felt experience of an energetic difference and shift occurring in the hands. Is this just a cognitive invention or is something really happening? In Chapter 14 (Research and Experiments) we review the research of Leonard Ravitz and our current updates. This fascinating work produces a graphical electrodynamic recording, in real time, of the millivolt changes in the left and right hands. The recordings show not only the energetic changes, but also that there is a difference between the left and right sides. Having established that these are energetic processes which occur at the microparticle level, we have opened the door to quantum field theory. We feel incumbent to provide a sketch, at least, of this fascinating topic to give you some foundation and open your curiosity to seek out more detailed information elsewhere. In Chapter 15 (Down the Rabbit Hole), we explore the quantum world and also speculate on what the future might hold. Finally, we have kept the hard science for two special papers, added as appendices, in which you can dive as deeply as you wish.

The Creative, Growing Edge

We conclude this introduction as we began, with a personal perspective from Richard Hill:

Despite my great good fortune and privilege of being mentored by Ernest Rossi, it has always been about where the experience takes me – how I change, where I grow. This book is an expression of what has emerged over the past decade of exploring new ideas and techniques with Ernest Rossi. Something certainly began on that auspicious day in December 2005, but the burden of responsibility for my development, however, has always been mine. It was my task to create effective and productive growth at the most exciting region of my being – my growing edge.14

The growing edge is the edge of your known space, your known capacities, your known comfortableness. From the growing edge you step into a creative space where everything is new and unknown. When you step out it is not a rupture or disconnection from who and what you are. It is just as it sounds – a point of growth. Always keep in your mind that you remain connected to everything you are. This adventure is growth into a space where you become more – more than you are right now. I (RH) am still expanding at my growing edge and Ernest Rossi tells me that, even in his mideighties, he also continues to push outward at his growing edge.

The creative, growing edge can be a difficult place to be. By its nature, you are there on your own. Even though you may be supported on many fronts, cheered on and encouraged, it is an unknown space. Our unique expression of what we learn, and the way we integrate that learning into daily life, is our expansion at our growing edge. Every therapeutic technique, process, and protocol is the expression of someone’s movement outward at their creative growing edge. In this context, there is no therapy, technique, or process that is ever entirely a perfect fit for you, because they have all been created at someone else’s growing edge. Some may well be a close fit, but this is why Ericksonian psychotherapy is so hard to reproduce exactly, because the only perfect Ericksonian practitioner was Erickson himself. We each must find our own best form and expression in order to be natural, comfortable, and unburdened as we practice.

We genuinely wonder where you will take this. What you might do with our words and ideas. How this book might enable, encourage, or inspire you to explore your growing edge. What will you create? It may be something very small. It may be a radical diversion. Chapter 9 (Curiosity and the Elephant in the Room) developed out of Richard Hill’s years with Ernest Rossi, but also out of his own life. What does this say to you? What do you have in your mind that may spill out beyond your growing edge? The intention of this book is to show you how we have done it, so that you can explore how you will do it.

One doesn’t discover new lands without consenting to lose sight, for a very long time, of the shore.

André Gide, Les faux-monnayeurs [The Counterfeiters] (1925)

To get to where we are now, however, there has already been a journey. It is natural to wonder about the history, about how things changed, and how they grew. It is natural, therefore, to begin this book with a historic review, and we are able to tap into the source, Ernest Rossi himself. Let’s ask him how it all began.

1 Erickson, M. H. (2008). The Collected Works of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Vol. 1: The Nature of Therapeutic Hypnosis, ed. E. L. Rossi, R. Erickson-Klein & K. L. Rossi. Phoenix, AZ: Milton H. Erickson Foundation Press, p. xii.

2 Rossi, E. L., Iannotti, S., Cozzolino, M., Castiglione, S., Cicatelli, A., & Rossi, K. L. (2008). A pilot study of positive expectations and focused attention via a new protocol for optimizing therapeutic hypnosis and psychotherapy assessed with DNA microarrays: the creative psychosocial genomic healing experience. Sleep and Hypnosis, 10(2), 39–44; Simpkins, C. A. & Simpkins, A. M. (2010). Neuro-Hypnosis: Using Self-Hypnosis to Activate the Brain for Change. New York: W.W. Norton.

3 Wampold, B., Flückiger, C., Del Re, A., Yulish, N., Frost, N., Pace, B. et al. (2016). In pursuit of truth: a critical examination of meta-analyses of cognitive behavior therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 27(1), 14–32; Connolly Gibbons, M. B., Mack, R., Lee, J., Gallop, R., Thompson, D., Burock, D. & Crits-Christoph, P. (2014). Comparative effectiveness of cognitive and dynamic therapies for major depressive disorder in a community mental health setting: study protocol for a randomized non-inferiority trial. BMC Psychology, 2(1), 47.

4 Ardito, R. B. & Rabellino, D. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 270; Miller, S. D., Hubble, M. A., Chow, D. L. & Seidel, J. A. (2013). The outcome of psychotherapy: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Psychotherapy, 50(1), 88–97.

5 American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychology, 61(4), 271–285 at 273.

6 Rogers, C. R. (1957a). A note on the “nature of man.” Journal of Counseling Psychology, 4(3), 199–203; Rogers, C. R. (2007). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44(3), 240–248.

7 Stiles, W. B., Honos-Webb, L. and Surko, M. (1998). Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 439–458; Hatcher, R. L. (2015). Interpersonal competencies: responsiveness, technique, and training in psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 70(8), 747–757.

8 Lambert, M. J. & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 357–361.

9 Schore, A. N. (2012). The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton; Storr, A. & Holmes, J. (2012). The Art of Psychotherapy, 3rd rev. edn. London: Taylor & Francis.

10 Miller, S. D., Duncan, B. L., Brown, J., Sorrell, R. & Chalk, M. B. (2006). Using formal client feedback to improve retention and outcome: making ongoing, real-time assessment feasible. Journal of Brief Therapy, 5(1), 5–22.

11 See: https://www.braininitiative.nih.gov/.

12 Rossi, E. L. (2004b). A Discourse with Our Genes: The Psychosocial and Cultural Genomics of Therapeutic Hypnosis and Psychotherapy. San Lorenzo Maggiore: Editris S.A.S.; Scheel, M. J., Davis, C. K. & Henderson, J. D. (2013). Therapist use of client strengths: a qualitative study of positive processes. Counseling Psychologist, 41(3), 392–427.

13 Rosenfeld, B. D. (1992). Court ordered treatment of spouse abuse. Clinical Psychology Review, 12(2), 205–226; Hopps, J. G., Pinderhughes, E. & Shankar, R. (1995). The Power to Care: Clinical Practice Effectiveness with Overwhelmed Clients. New York: Free Press.

14 Rossi, E. L. (1992). The wave nature of consciousness. In J. K. Zeig (Ed.), The Evolution of Psychotherapy: The Second Conference, 216–238. New York: Routledge.

Chapter 1

The History of Mirroring Hands

Ernest Rossi in Conversation with Richard Hill

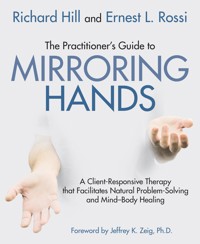

Figure 1.1. Richard Hill and Ernest Rossi in conversation, June 2016

In June 2016, I met with Ernest Rossi and his wife, Kathryn Rossi, at their home in California. The main reason for the visit was to explore the writing of this book. We met every day over seven days, recording over 25 hours of interviews and conversations. In the second session on day 1 of my week with the Rossis, I asked Ernest Rossi, “What is the history of the Mirroring Hands approach? How did it emerge from your ‘apprenticeship’ with Milton Erickson?” I have reproduced the bulk of the answer. The transcript has been edited for clarity and some additional commentary has been added. Italicized words indicate emphasis.

In this transcript, and throughout the book, Richard Hill is represented by RH and Ernest Rossi by ER.

From the Rossi/Hill Conversations, 2016

Los Osos, California, June 1, 2016, 2pm

RH: Maybe this is the opportunity, what do you think, in among all the questions that I have, one was, really, to hear from you about the emergence of this Mirroring Hands approach.

ER: Oh … what’s the essence, profoundly the essence …

RH: Yes!

ER: I remember once being introduced from the lectern, “And now Ernie Rossi will show his approach with the hands” (we laugh). Isn’t that silly?

RH: And that was … that?

ER: I think, “He doesn’t get it.” So, what doesn’t he get? We have two sides … you know all this stuff about the left and right hemisphere? It’s all true from the quantum field theory perspective of consciousness and cognition, empathy, personality, brain plasticity, molecules, and gene expression. all the way down to the quantum level. It’s built in here (ER indicates his head).

RH: Yes, I’m very familiar with much of that …

(ER pauses as he contemplates where to begin.)

ER: I was with Milton Erickson many times when David Cheek was there, so it was a threeway conversation between us … just like I was there many times when Ravitz was there … and I learned in these informal shop-talk trialogues a lot that the public’s perception of therapeutic hypnosis seemed to have no appreciation of …

* * *

Erickson might reasonably be considered one of the major thinkers about modern psychotherapy and therapeutic hypnosis. He qualified as a psychiatrist in the 1920s and conducted extensive research in the field of therapeutic hypnosis. The Milton H. Erickson Foundation, led by Jeffrey Zeig, Ph.D., continues the legacy of Erickson through education, a huge archive, and the organization of an annual conference to celebrate his work and the ongoing evolution of psychotherapy.1 Erickson’s publications are best recorded in the 16 volumes of The Collected Works of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. (2008–2015) edited by Ernest Rossi, Kathryn Rossi, and Roxanna Erickson-Klein.2 He was a master teacher. The people who spent time with him, learned from him, and developed their work in association with him are a “who’s who” of modern psychotherapy.

Ernest Rossi regularly visited Erickson, often monthly, and usually for about a week, beginning in 1972 until Erickson’s passing in 1980. Many significant people would visit Erickson, so being in the Erickson household was a fertile ground for any developing student, researcher, or writer. Leonard Ravitz, a psychiatrist from Yale, was a student of Erickson from around 1945. Ravitz was involved in the pioneering work of the measurement of human electrodynamic fields and the variations between the left and right sides of the body. In the 1950s, he and Erickson applied this technique to subjects during hypnosis. Let it suffice to say that the apparatus had similarities to other electrodynamic measuring apparatus such as an electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures brain activity, or an electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG) machine, which measures the electrical activity of the heart. He and Erickson mentored Rossi in the use of the measuring apparatus and they conducted a number of experiments with patients, on themselves, and with family members during the mid-1970s, much of which is documented in Ravitz’s book Electrodynamic Man.3 During my visit with Rossi, we conducted several experiments, including the first ever measurement of two people in trance, using a modern version of the apparatus. Rossi and I became the “left” and “right” sides of a dyad connected by the holding of hands to create the circuit. The details of our solo experiments and other experiments conducted previously are detailed in Chapter 14.4 The important aspect to note is that the measuring electrodes were adhered to the palms of each hand. The voltage was recorded as a line on a strip of paper that showed the variations over the time of the experiment. The right and left sides were recorded as different lines, so it was possible to see the variations happening in each side and the differences in activity between the two sides of the body.

Dr. David Cheek was also an important mentor for Rossi. He began his medical career as a specialist in gynecology and obstetrics. He became very interested in hypnosis and developed the process of “ideomotor signalling.”5 Cheek first learned this from hypnosis training seminars presented by Erickson in the 1950s. In essence, the positive, or “yes,” attribution was given to one finger and the negative, or “no,” to another. The subject is trained to raise one finger or the other as a response. During trance, it was found that one or the other of these fingers would rise or move in a non-conscious way – “almost by themselves” – indicating a connection with implicit, unconscious regions of the subject. These movements may agree with the conscious dialogue or may disagree to indicate discord or incongruence between the conscious and non-conscious worlds of the subject. The non-conscious, or non-selfdirected, action is similar to hand levitation which is also an ideomotor response that occurs “by itself ” and is a behavior during hypnosis that can indicate a state of trance. The important aspect to note is that the different finger responses reflect opposite and mirror aspects of the situation being investigated.

* * *

ER: So, I’m reading the literature and sitting with these guys and I realize that in the literature, there is a term – the ideomotor – the idea gives rise to a push, an activity … that’s what I connected with. I’m intrinsically a top-down person. It’s the idea that evokes (ER indicates with his hands a movement down the body from his head).

This was one of the things I found brilliant about Cheek that the rest of the hypnosis world did not understand. Apparently, there were some high science guys who pride themselves on their “science” and “experiment” and “research” in the field of hypnosis who demolished Cheek.

What they found was unreliability in the movement of the fingers. Cheek says, “This is your ‘yes’ finger and this is your ‘no’ finger and this is your ‘I don’t know’ finger.” These guys did some experiments and found the subjects to be unreliable, “Cheek is not scientific!” (ER describes this with high pantomime.) They turned the whole world of hypnosis and psychotherapy against the idea of the “ideodynamic.”

But … if you stop to think about it … ideo means “idea,” but it also means “the individual.” So, what kind of simple-minded mechanism would it be if every time I say, “Yay,” your yay finger goes up, and every time I say “Nay,” your nay finger goes up? In other words, human complexity is involved, not human unreliability.

These scientific types were looking for some objective science, just like in the 1890s – the beginning of experimental psychology in Würzburg, in Germany – and they said, “Ah, psychology is a science, an experimental science” and it’s been futzing around with the subjective humanities ever since … Really, these so-called scientists were talking about the experience of the world only from their left hemisphere – the verbal, the mathematical – rather than the right hemisphere – the episodic and experiential. So, it was an effort to see the truth. I saw the truth in Erickson and I saw the truth in Cheek. But, I saw that the finger signals could be unreliable and it concerned me too.

So, I did a book with Cheek,6 and I developed all those paradigms, all those techniques, all those boxes in the book, and they really are still good. I haven’t used them that much because I moved on to other things, but I was looking for something else because there was one thing that did bother me – the finger signals – as some people just didn’t show them.

Somehow, when you were in the atmosphere of Cheek, he carried such an authority that the subject’s finger really did go up by itself. Other people, the scientific types, said it wasn’t by itself, Cheek was “programming” you. So, I was looking for something that was less programmable, so to speak …

You’re really asking what were the steps that led to my inventing the Mirroring Hands technique … It was the idea of the ideodynamic – the essence of that so-called “trance” thing – it was also the ideodynamic that was a split between my point of view and Cheek’s. He called it “ideomotor,” but if there is ideomotor, there must be ideosensory, and I thought the word “ideodynamic” included both of them. When I wrote the book, I used the word ideodynamic, but he really never went for that.

RH: How did you get to using the hands?

ER: I think it really just came out of body language. (ER demonstrates the use of one hand and then the other while in discussion.)

So, I thought, “Why not use the whole hand?” Now, that’s the connection with Erickson, who invented the hand levitation approach in therapeutic hypnosis. I’m not exactly sure of when, in my memory, but I believe that I put the ideas of Erickson and Cheek together to create the mind–hand mirroring approach to therapeutic hypnosis. Erickson did this (ER raises his arm off the chair like a hand levitation) but, actually, this was kind of hard for a lot of people, but maybe …

(ER’s eyes sparkle in a numinous a-ha moment of discovery) … Oh, now I recall the connection …

This was one of the earliest ideas about what hypnosis was – that it was a manifestation of electromagnetism. I think … I don’t know if it was me or somebody else … sometimes I really do think, “Was that really me or did I read that somewhere?” Anyway, those old historical books on hypnosis show pictures of old guys with big eyes … and so-called magical gestures … I know I’ve seen in these historical documents the idea of magnetic movements, but I found, somehow, a connection between magnetic and hands and fascination in what I call the “novelty-numinosum-neurogenesis-effect,” which is the scientific basis of therapeutic hypnosis.7

So, if you put your hands together like this (placing his hands in front and separated) you can feel – ideosensory – you actually feel it subjectively … Now, as I closed my eyes when I demonstrated that I was really feeling it … (acts out his thinking processes) … Was I really feeling the pulling together? Yes! But could I also feel a “no” response, where the hands come apart? Right now with you, Richard, I am experiencing that pushing apart …

Now, when I did this, I put together the ideomotor with ideosensory … Now I’m speculating that this very fragile subjective experience is a quantum quale of inner sensation and perception that can only be felt and realized by me, myself, and I. It is the essence of the self, a secret sense of my aliveness that no one else can possibly experience! Shall we call it the “Quantum Sense of Being” or the “Uncertainty of Self ”? I wonder … is this the essence of the very fragile and numinous experiences of empathy, compassion, relationship, and healing during mind mirroring between people in love in real life, as well as in the psychotherapeutic relationship? I’ve never written about this, have I?

RH: Not really … no.

ER: So, here was Rossi “doubling down” so to speak. I’m trying to increase the person’s hypnotizability – I don’t like that word – I want to say, instead of hypnotizability, a quantum hypersensitivity to one’s inner ideodynamic … a quantum quale of inner sensation and perception. Part of my shift now, by the way, to the quantum field theory is that finally somebody got it. There was an article in the American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis and they said, “Ernie Rossi said that it was not so much suggestion …” and they say correctly, “Erickson was not a genius of manipulation … Rossi said it was more correct to say that Erickson was a genius of observation.”8

RH: You say this in volume 6 of the Collected Works …9

ER: Now that heartened me. Somebody’s got it! Yes, that’s what I really think. That’s the new connection to the quantum level of human experience …

RH: … the observation …

ER: … and the deeper quantum level of sensitivity. Quantum and hypnosis are not strange and weird. They are another dimension of being hypersensitive to your inner world.

The problem of psychotherapy is: people have problems. Why? Because they don’t know how to listen to themselves and their own impulses, their own truth, their own myth. Why don’t people all follow their inner passion? Because the outside world overwhelms them.

RH: Following your bliss is what Joseph Campbell was saying …10

ER: Yes! The typical teacher says, “Now you are going to make an ‘a’ like this, not like that …” and the kid has to practice making an “a” – a small “a” and then a big “A”. So, a lot of learning that is taught to kids is learning how “not to.” There are a million ways, infinite ways, of “not to,” but apparently only one way that is “correct.”

RH: This is the winner/loser idea of mine that is based on the idea that there is a winning – a way that wins – and everything else loses …11

ER: Yes …

RH: … and losing is bad.

ER: … and so, we see the “power” instinct …

RH: Yeah …

ER: … aggression, rather than sensitivity and positive empathy. That is what I am exploring – can humans educate themselves to the values of quantum level sensitivity and well-being, rather than stress, anxiety, addictions, and depression?

RH: Yes.

ER: I was about to say “subjective awareness,” but subjective awareness can be your finest quantum quale level of sensitivity. So fine that many people don’t get it because it is directly dependent on your particular brain structures and the classical as well as quantum contingencies environment. All of us have infinitely different possibilities in life …

Basically, people have problems because they are overwhelmed by the outside world saying “it’s my way or the highway.” By saying we have to do it in only one way it just deepens the pathology. So, a politician is truly great when you have someone like Lincoln, say, give voice to something that is emerging in the fragile shadows of human consciousness and cognition …

RH: The zeitgeist?

ER: Yes, we should not make slaves of each other, and so forth. So, I don’t think I ever wrote it, but the basic human problem is that you’ve lost your voice. No one told you to be a poet when you were a child … it’s the educational system … reliance on group testing and competition … the competition for who is going to be the dominant voice, rather than who has the most sensitive understanding … who is going to see the world in a new light, like Einstein.

You know that Einstein was a “duffer”? He wasn’t that good at mathematics and he was an inspector third class in the patent office.

So, people have problems not because they have problems, but because nobody taught them how to respect their own genius. Everybody has a genius when they learn how to optimize their best self! How do we help each other to find our own opportunities in self-development? That’s the real problem of nation building for politicians – not perpetual self-aggrandizement, which is a crime …

So, now it’s quantum sensitivity, observation, empathy, and compassion for yourself and others that are the important things, not suggestion …

RH: And certainly not direction …

ER: You bet … And so, when I wrote The Symptom Path to Enlightenment in 1996, it suddenly came as a great insight to me that the symptoms, really, are your guide.12 Symptoms show where you are bumping against consensual reality, and so you’ve got to learn to work on that … But, of course, the outside world isn’t fair. It doesn’t say, “Oh yes, that’s right. You’re really right after all, Richard …” I know a politician currently fighting for dominance who would never say that to you.

So, this is how I made the connection between hypnosis and quantum self-sensitivity and the NNNE. The dominant outside world said, “It’s not your self-sensitivity and self-creation that’s important, it’s my direction that’s making everything good for you.”

My struggle has always been: how do I get the person to be more sensitive to themselves, to explore their own best experience, to find their own unique truth, and then when they find their truth, their passion, so to speak, how do they develop more skills to share their truth with the world around them? This is stage 4 of the creative cycle13 – you do your inner work, using the NNNE to create the best of yourself and give back something of value.

This became a very important transition from Cheek, who pointed out which finger would say “yes” and which “no.” My first shift away from this was to move the focus to “Let’s see which will be your ‘yes’ finger and which will be your ‘no’ finger.” We would get the client to say “yes, yes, yes, yes …” and see which finger moved. This is a sensitive process. When Cheek would work with me, though, my finger would really go … But that didn’t happen for everyone. Did you ever meet Dr. Cheek?

RH: No.

ER: He was a rather large presence – a wonderfully benign family doctor. You’d love just looking at him. He’d smile and you’d feel comfortably, confidently contained – wrapped in the wings of his well-being …

Then I went through a phase where those fingers could be like magnets. I went through all those transitional things and finally I came up with the importance of inner awareness and self-care in daily life (ER demonstrates by making a large sweeping circle with his arms, with his hands very slowly swirling in the surrounding space) … I found that in my personal experience, even though I am not particularly “suggestible,” even I can feel something. When I’m working with someone, I’m habitually in deep empathy and rapport. I try to extend my sense of union with the person by asking, “Can you feel how one part of you is pushing away what you no longer need and another part of you is pulling together what you need to receive?” And the person would look and see their hands slowly going together, and I would ask, “Are they really going together or are you just doing that deliberately?” and they would say “No, I’m not doing it!”

And then, one day, after a person’s fingers touched, I dared to ask, “OK, now what would happen if the magnets, the inner forces, reversed? Could you feel, sense, the hands pushing apart?” and sure enough the hands would draw apart. I would say, “Are you just trying to be a good subject for me or is that really happening all by itself?” So, happening by itself, what some hypnotherapists would call “a mild sense of dissociation,” became a very important thing for me in conceptualizing changing novel states of consciousness and cognition. I now speculate that such heightened states of inner ideosensory dynamics may be a currently evolving dimension of consciousness at the quantum level of the NNNE.

So, if the NNNE is happening by itself, well, of course, everything in nature is unconscious on a quantum level of uncertainty, probability, and potentiality for creative change. This is how we are making contact – a connection between newly evolving consciousness, cognition, dreams, and the probabilistic nature of the quantum unconscious. So, for many years, this is how it was – facilitating essential “yes” or “no” states of emotional transition through my Mirroring Hands technique, drawing brain/mind states together or pushing them apart via the NNNE. Then came the final switch: I discovered I could do this without using the hypnotic metaphor. I could say, “Place your hands together, about chest height and the palms facing each other – just like mirroring each other – and let’s see what starts to happen – all by itself.”

I think that the first time I said this it was a mistake, I forgot to use the term “magnetic.” I just forgot to use the term. Maybe I was tired that day, but I said, “Let’s see if those hands come together or maybe push apart.” Of course, I meant like a magnet, but I forgot to say “magnet” and I found that it was really happening all by itself without the magnetic metaphor which was from historical, classical therapeutic hypnosis.

RH: So, no suggestion?

ER: Right. Then came the next step which was … I’m trying to remember how I made the jump … “Can you get a sense of which hand feels like it is expressing your problem?” And that was very easy for people, whether they believed they were experiencing hypnosis or not! Hand levitation had its problems – not everyone can do it. Fingers weren’t reliable, but everyone could suddenly experience, “Oh yeah, this hand feels like the problem …”