20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: J A Allen

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

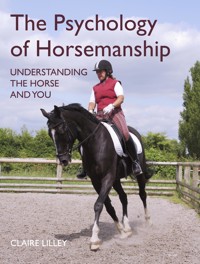

Horses are fascinating and perceptive creatures. Developing a thorough understanding of how a horse interprets the world around them and deliberately being self-aware as a rider, are the essential skills to a successful and fulfilling partnership. In The Psychology of Horsemanship, well-known equestrian author and horse expert, Claire Lilley, shares her passion and knowledge about horses and riders developed from over forty years' experience in the equestrian world, and more recently several years in the mental health profession. Divided into three sections, the book covers: Equine psychology - the horses's senses, primary responses and emotion; Training psychology - the rider's communication, training and learning from past experiences; Relational psychology - the goals, the development and the challenges faced in successful horsemanship. With high-quality photographs, diagrams and extended real-life examples, this book explores the application of psychology to the world of horses and how the understanding and evolvement of the horse-rider relationship impacts on both mental and physical development.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 266

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Psychologyof Horsemanship

UNDERSTANDING THE HORSE AND YOU

The Psychologyof Horsemanship

UNDERSTANDING THE HORSE AND YOU

CLAIRE LILLEY

J.A.Allen

First published in 2020 byby J.A. Allen

J.A. Allen is an imprint ofThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Claire Lilley 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 908809 90 2

Photos by Dougald BallardieIllustrations by Carole Vincer

DisclaimerThe author and publisher do not accept responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it.

FrontispieceClaire’s equine partner for many years was Carina Amadeus. He was a very special horse and the inspiration for much of her work.

Contents

Introduction

PART 1: UNDERSTANDING THE HORSE: Equine Psychology

1THE SENSES

2PRIMAL RESPONSES

3PHYSICALITY AND TOUCH

4EMOTION AND INTUITION

PART 2: UNDERSTANDING YOURSELF: Training Psychology

5COMMUNICATION

6LEARNING, TRAINING AND EDUCATION

7DISCIPLINE: ESTABLISHING BOUNDARIES

8THE EFFECT OF PAST EXPERIENCES

PART 3: UNDERSTANDING YOUR PARTNERSHIP: Relational Psychology

9FORMING RELATIONSHIPS

10CHALLENGES AND COPING STRATEGIES

11SPORTS PSYCHOLOGY

12THE GOAL OF HORSEMANSHIP

Acknowledgements

References

Index

Introduction

There are fundamental elements that constitute horsemanship: mental, physical and spiritual. As human beings wanting to bond with our horses, we must use all our available skills: our senses, our intelligence, our physical body awareness and intuition. Horses are better at doing this than we are, so there is a lot for us to learn from our equine partners. Historically, horsemanship is about developing the partnership between horse and rider. It is about developing mutual trust, respect and understanding and love – the foundations of a rock-solid relationship.

Horses have been domesticated for centuries, and lived with mankind as family, depending on each other for the very basic elements of life: food, shelter and companionship. Man and horse went to war together, each relying on the other for survival. Many of the instigators of the classical schools of horsemanship, such as the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, had a military background, demonstrating their prowess and skills in training their horses. Horses continue to have an important presence in the police force and the army, and are particularly impressive in the many royal duties the Household Cavalry performs.

Horsemanship is about developing the relationship between horse and rider.

In more recent times, without the need to take horses into battle, they have become important in sport. While hunting and racing have been around for many years, the old military influence was influential in the development of many more newer equestrian sports. For instance, the sport now called eventing was originally based on the way to prepare cavalry horses for active service and was, for some time, called ‘the military’ because of this, before being known as ‘horse trials’ and more recently and informally by its current name. It is also the case that many of the early proponents of showjumping and dressage were from military backgrounds and, of course, cavalry officers were influential in the introduction of polo to the western world.

Equestrian sport generally has flourished since becoming a regular part of the Olympics, first seen in Paris in 1900 as an individual showjumping competition, then from 1912 in Stockholm to the present day, initially via dressage, showjumping and eventing, with other disciplines now included, such as driving, vaulting and the modern pentathlon.

In modern times, while horses in some areas are still used as pack and draught animals, for ploughing and other farm work, most are owned for pleasure and sport, or simply for company and companionship. In respect of the latter, they also have special value in psychotherapy, offering unconditional positive regard by accepting people for who they are, without judgement or preconceptions and showing a sensitivity to human emotions and body language.

An insight into gaining that special bond between people and horses, where the magic ‘just happens’, is the aim of this book: to become familiar with the mental and physical responses in the human body to a degree whereby being with a horse, whether riding or handling, feels natural, easy. This is about not being ‘in the way’ of the horse, but guiding, listening, feeling. Being truly ‘at one’ with a horse, with mind, body and soul, can be an amazing experience. This book explores the fascinating world of the human/horse relationship and the implications of this bond on life in general – for example, relationships, self-awareness and communication.

A special bond between horse and rider where the ‘magic just happens’ is a wonderful thing. Even with a relatively new partnership, as with this horse and rider, there is a sense of true connection between them. (Photo by NakPhotography)

Horses mirror our feelings and our unconscious processes; being with them and developing a relationship with a horse is very special. Taking time to really notice what is going on in relation to the horse develops self-awareness, not only physically, but also mentally. Learning about how a human being relates to a horse can influence life skills – for example, coping with stressful situations, perhaps in work or sports environments. The possibilities are endless.

Horses are very aware of non-verbal communication: our body language, how calm and confident we are, or not. This applies to all aspects of horsemanship, whether we are riding or handling them, or simply in their presence. They pick up things about us we are not even aware of! Understanding how a horse interprets what we do helps to create a special bond, reaping so many benefits in training. In contrast, issues that arise from misunderstanding can have a hugely detrimental effect on progress.

This book is written from my own experience as a horse owner, riding instructor and psychotherapist. The views are my own, supplemented by my own personal research, along with other findings and viewpoints, which can be found in the reference section. Research into the realms of horse psychology and the relationship with humans is continually evolving. How the mind and body of both horse and rider function together is fascinating to me and even more so in partnership with the horse. I am no expert on neuroscience, but my basic understanding of how the brain works is integrated with practical experience to hopefully shed light on the fascinating world of horsemanship. Having worked in the equestrian industry for many years as a trainer of horses and teacher of riders, I came to the conclusion that in order for horse and rider to progress as a partnership, a deeper knowledge of psychology would be of benefit for human pupils. This would help them to assess their own mental processes, doubts and fears. This quest for knowledge has led me along the path of psychotherapy, finding a new vocation and a renewed enthusiasm for riding, as well as a new career. Understanding the workings of the equine mind has benefited my own relationship with my equine partners, and brought further insight and fascination into training horses. My hope is that this book will inspire curiosity and encourage the asking of questions by horse owners, equestrian professionals and those working in the mental health sector, where relationships are so crucial to human development.

Any mistakes within the book are entirely mine. No parallels with any individual horse or rider are intended: where examples are given, they are generic or taken from my own personal journals. At the end of each chapter are questions you may like to consider, to give yourself an insight into your own relationship with the horse. There are also thought-provoking quotes throughout the book for you to contemplate.

I hope this book proves informative and of interest to anyone who is fascinated by the relationship between horse and human, and how this special bond can be deepened by having an awareness of the psychological aspects of horsemanship.

Part 1

UNDERSTANDING THE HORSE:Equine Psychology

1The Senses

It is difficult to work with and to train horses without making a study, even subconsciously, of their behaviour and the ways in which the individual horse might react in certain situations.

Monty Mortimer

What a horse does under compulsion (as Simon also observes) is done without understanding; and there is no beauty in it either, any more than if you should whip and spur a dancer.

Xenophon

As mammals, both horses and humans have the same senses and the same processing system. Understanding how a horse senses his world helps us to understand his reactions and behaviour, which is essential to building a relationship between human and horse. Horses are sensitive and perceptive, noticing our reactions and behaviour too, so how we react to them affects how they react to us. This chapter gives an overview of the senses and how they relate to our partnership with horses.

Horses are much better at using all their senses to assess their world than people are.

THE BRAIN AND THE SENSES

The brain is the central control for the body. It controls thought, feeling, learning and memory, and governs movement, responses and reactions, and bodily functions, keeping the heart beating and the lungs breathing. The skull and the meningeal layer, encasing it in cerebral fluid, protect it. The adult human brain weighs about 3lb; the horse’s brain weighs approximately 2½lb. According to current scientific research, there is also said to be an equivalence between the intelligence of the horse and a twelve-year-old child. The equine brain structure is generally similar to that of the human brain, but there are some variations in usage: the horse uses most of his brain to analyse his surroundings and for movement.

The brain structure is complex, but put simply it is made up of three parts: the hindbrain (also known as the primitive or reptilian brain), the limbic system (emotional brain) and the forebrain. The biggest part of the forebrain is the cerebrum, the main body of the brain. The cerebrum is divided into two halves, or hemispheres, joined together by a bridge-like structure, the corpus callossum.

The horse’s brain has a smaller frontal lobe than a human’s (which, in the human, is used largely for problem-solving and language), but the horse’s cerebellum, to the rear of the brain and responsible for movement, is larger than a human’s.

According to research, the left side of the human brain is said to be the logical side, and the right side the intuitive and creative side, with the right side of the brain processing senses and controlling motor function in the left side of the body, and vice versa. In the horse, it is suggested that the left side of the brain processes learning, and the right side emotion and threat, but evidence to this effect is scant and seems to be conflicting.

This chapter focuses on the outer layer of the cerebrum, the cerebral cortex, which interprets input from the senses.

Frontal brain (human).

Equine brain.

A foal has to learn to stand up and must be able to run with his mother, almost from the moment of birth (and usually within an hour), using primal instincts originating from the hindbrain. He instinctively knows how to find nourishment (initially to suckle), and will learn by mirroring his mother how to move his limbs, eat grass and drink water. A human child also knows instinctively how to take milk, and both the child and the foal notice body language and expression from the start of life. A human child takes a lot longer than a foal to learn to walk, but learns to communicate by talking.

In both the human and equine brain input from the senses is processed in the neocortex, or forebrain. The sense of smell is used for detecting information from the surrounding environment, determining safety, or danger. The olfactory system is the oldest part of the cortex, and is directly linked to the emotional brain, without passing through the thalamus, the filter system for information.

The occipital lobe is the only part of the brain dedicated to just one sense – vision. Visual information is also processed in the neocortex, as is auditory (sound) input. In order to see, light impulses are analysed; to hear, sound waves are processed, both senses requiring energetic input. Taste is connected to the pain and pleasure responses in the body, enabling distinction between what is tasty and beneficial to eat, and what is unpleasant, and may be harmful.

The thalamus relays information to the cortex from the sensory organs, such as the fingers, nose, eyes and ears. Conversely, to use the senses, messages pass from the cortex to the thalamus before being transmitted to the relevant parts of the body, for example the hands in order to touch something.

Smell

Smell is the first sense to evolve from birth, and has direct links to the emotional centre of the brain where the primal responses are triggered (seeChapter 4) and memories are recalled. Memories of different smells form by learning which are pleasurable, or distasteful.

In mammals, receptors in the nose are stimulated by different odours. Smells reach these receptors through the nostrils and from the top of the throat, with odours being released as food is chewed, hence the senses of smell and taste are closely linked as identifying factors. Molecules of various substances become trapped in mucus at the top of the nose, where they combine with olfactory receptor cells. These send information to the brain via the olfactory bulb.

Each smell has a unique receptor identity from which it is identified by the brain. The olfactory tract relays information about a particular smell directly to the amygdalae (which form part of the limbic system – seeChapter 4) and hippocampus (where memories are formed) for processing before being relayed to different parts of the brain.

The horse’s sense of smell

Horses have a very good sense of smell, with which they can identify, among other things, predators, other horses and people.

The horse has large nasal cavities and flares his nostrils to breathe in smells. The shape and location of the turbinate bones inside the head cause inhaled air to roll around, warming the air and distributing the scent to the numerous receptors in the cavity. Horses have a vomeronasal organ, situated under the top lip, and peel back their top lips to expose this area to a scent (this is known as the flehmen response). Stallions will use this to smell whether a mare is in season, or to sniff dung to gain information about other horses. Smelling another horse’s dung is, to a horse, rather like reading a text message. They learn a lot about who was there and why and, as mentioned, their hormonal state.

Horses will sniff another horse on meeting. They touch noses, and flare their nostrils to gain as much olfactory information as possible. They sniff humans too, and recognize the familiar scent of their owner, and the unfamiliar aroma of a stranger.

The horse is able to flare its nostrils to breathe in smells.

The horse uses its sense of smell to gain information about people, recognizing the familiar smell of their owner.

Smells, overall, are very interesting to a horse. They can smell food, water, and detect the smallest amount of medication hidden in their food. They can react extremely to strong odours, or a smell that reminds them of a bad memory. They pick up scents while out on a hack, and may refuse to go past a place for what their rider may see as no reason, but to a horse the message is ‘danger’.

The familiar smell of a caring owner is reassuring to the horse.

EXAMPLE 1

I had a horse who reacted fearfully to the smell of cement he detected on my husband’s hands. This horse had previously been owned by a builder, who we assumed had given this horse a hard time, and that smell evoked a fearful memory. On smelling cement, he would leap to the back of his stable, highblowing, warning the other horses of imminent danger. He held his head high, his body tense, and ready to run. My husband stood calmly just outside the stable, and removed his gloves. I took them well away, so the horse could not smell them anymore. After calming words, he settled, and relaxed.

EXAMPLE 2

One of our horses would smell a dead badger at 100 yards, and refuse to walk past it. He was a brave horse in many ways, but his sense of smell would trigger his flight response to this object and he would want to canter off down the road. Over time, he learned to trust his ride; his flight reaction lessened to becoming alerted, in effect being able to contain his energy, collecting himself, arching his neck, and passaging past, with a lot of snorting. The snorting clears the nasal passages, enabling the horse to heighten his sense of smell.

The rider’s sense of smell

In the human nose, the mucous membrane lining each nostril contains olfactory cells, which react to chemicals that are breathed in. These cells relay information to the brain, which can distinguish between thousands of different smells, which are retained in the memory. A certain smell may evoke fear, pleasure or displeasure, resulting in responses such as difficulty breathing, or headaches. The smell of horses in a stable may trigger a memory, perhaps of happy childhood days spent at the local riding school; the whiff of a muckheap may take you back to working as a student at a yard, and that memory may be pleasurable, or bring back a sense of anxiety at training for exams.

Familiarity with the horse’s smell is part of owner and horse getting to know each other. The owner may be attracted to their horse’s smell; in a good relationship his body, his dung, his urine will be acceptable. A horse they may not get on with might smell abhorrent.

Taste

As mentioned earlier, the senses of smell and taste are closely linked, both being about detecting substances, and sometimes pretty much in tandem. The horse’s mouth and tongue are lined with sensitive papillae, which inform him what he has in his mouth. Rough handling of the bit in his mouth damages these, and a loss of papillae in the tongue diminishes the sense of taste, which has a knock-on effect on appetite by affecting the horse’s decision-making process on what to eat. Horses like sweet and salty tastes; a salt lick goes down well, as does a piece of apple. Horses use their sense of taste, combined with their sense of smell, when grazing to identify plants that are good to eat, or toxic, and are selective about which grass tastes the best; the texture of coarse grass, or soft clover. Horses generally avoid eating what is not good for them, unless grazing is poor and vegetation scarce.

A horse will taste not just the food he eats, but also the bit in his mouth. What relevance does this have to the partnership? In the first instance, he will relish a titbit as a reward for good work, cementing the bond with his rider. Consistency in reward builds trust. Secondly, when training a horse to take a bit in his mouth, offering him a tasty handful of grass as he takes the bit makes the process pleasurable, encouraging him to mouth the bit, normalizing the process.

The horse relishes a titbit after work, cementing the bond with his rider.

Vision

The horse’s vision

Understanding how a horse sees gives the rider information about how he reacts to certain situations – for example why he spooks at a rubbish bin, or why a rabbit scurrying across the grass causes him to shoot forwards.

The horse’s eyes are set high on the sides of his head, ideally positioned for spotting predators when grazing, and the horse has a wide range of vision around his body. Vision to either side is monocular (with each eye seeing independently of the other), which means that horses can see different things with each eye giving separate information to the brain. Both hemispheres of the horse’s brain are connected by the corpus callosum, sharing information from both eyes, so theories pointing to the horse’s brain processing visual input differently from the human brain, by seeing an object anew in each direction, are questionable. However, an object may look different from each direction, and other factors such as the orientation of the object affect how it looks to the horse.

Using monocular vision, horses have a poor perception of depth; a trailer may be seen as a black tunnel. In such circumstances, a horse will move his body and head in order to use binocular vision to get a better idea of whether there is a need to run away. The pupils in the eyes are horizontal and slit-like in appearance, optimizing the horse’s ability to scan the horizon for danger.

Parts of the horse’s eye.

The range of binocular vision to the fore is approximately 60 degrees. The horse will raise his head when alerted to danger, and use binocular vision to look into the distance, focusing with both eyes at the same time, looking straight ahead.

Despite the wide overall field of vision, the horse has two blind spots: one between the eyes, and the other directly behind his tail. He cannot see what is low on his back, either.

Horses can see well in the dark, detecting movement in low light conditions. They apparently see colour as shades of grey, green, yellow and blue. Some studies show that they cannot distinguish between red and green, but are aware of contrast, particularly black and white. Other studies say they cannot distinguish between red and blue.

In addition to uncertainty about the horse’s colour vision, it is difficult to test the quality of a horse’s vision. A horse with impaired sight can still ‘see’, according to studies. The horse uses other senses to gain information when blindfolded. In fact, quite how horses actually see is not fully understood. The eye is an optical instrument, relaying visual information to the optical cortex in the brain, but the way a horse ‘sees’ his environment involves other sensory perceptions that are not fully understood.

The horse’s range of vision when grazing.

The rider’s vision

The human’s eyes are set on the front of the head. Having binocular vision, people will turn their head in order to focus on an object and to judge depth of field and thus distance. With binocular vision, people can distinguish foreground from background, recognize objects from many orientations, and get a sense of space, colour, light and shadow. They see movement. Light-sensitive nerve cells in the retina, known as cones, distinguish colour and are responsible for sharpness of vision, and rod cells are used for peripheral and night vision and to distinguish movement. Cones are situated in the centre of the retina, and rods to the outside. Information travels via the optic nerve as impulses to the thalamus in the brain, where distinction is made between colour, structure and movement. Focusing on an object straight ahead uses central vision, and what is seen around that object to either side, to a total extent of 180 degrees, is picked up by peripheral vision. The human pupil in the eye is round, and the aperture can restrict to focus light into the eye to see detail. Humans are not active at night, so night vision is not so important for people as for horses. Positive thought, and fear, dilate the pupil.

Comparison of horse’s eye to human’s eye.

Vision is used by horse owners when caring for their horse, assessing his well-being in terms of stable management, and the use of sight plays an important part in observing the horse’s welfare. Visual signs indicate his behaviour: whether this is normal for him or whether he shows signs of discomfort or stress, and to assess whether he is healthy.

USING THE SENSES

Noticing what you think when you see an object is very informative. For example, looking at a flower, you notice its colour, shape, structure and whether it is still, or moving in the wind, and how far away it is. You may recognize the type of flower, a rose, for example. You know that roses have a scent, so you could be tempted to smell the flower, involving another sense. You may want to touch it to feel its texture. It may evoke a memory; this flower may remind you of a person or a place, a happy or sad memory. You know a rose would not be edible and that it is not frightening, but that its thorns could hurt you if you touched them.

EXAMPLE

When riding, the rider would look for potential danger, and assess any action that might be needed. The rider sees/perceives differently from the horse. The rider might notice a herd of black and white cows in the next field. The horse would notice the movement of the cows, their contrasting colour. His reaction would be to stop and raise his head to focus both eyes (binocular vision) on the perceived danger, tensing his body in preparation for flight should he feel threatened. His heart rate would increase, and he would use his sense of smell, flaring his nostrils to gain as much information as he can about imminent danger.

Vision of horse and rider as a pair

When the horse/rider partnership is in operation, they have two sets of eyes between them, and it is important that the dual vision is used in a co-operative manner. For this to happen, it is important that the rider, in particular, is mindful of how the horse sees, and how he responds to what he sees.

When jumping, the horse needs to raise his head on the approach to use binocular vision to see the fence and to judge distance. The rider focuses on the top rail of the fence to work out the point of take-off. The horse focuses on the ground-line of the fence when deciding his take-off point and lowers his head at the point of take-off.

Jumping is one example of the fact that the horse’s neck position has a significant effect on his vision. The rider overbending the horse’s neck (hyperflexion) causes the horse to look at the ground, or even back at his chest or knees, depending on the severity of the positioning caused by the rider. This unnatural position goes against the horse’s inclination to look forwards. In this posture, the horse cannot see forwards, and is working blind, totally reliant on the rider for guidance. In contrast, riding the horse in a correct rounded outline, with the nose line vertical, or just in front of the vertical (which is beneficial for the mechanics of the body), also allows the horse to see with both binocular and monocular vision, while maintaining his focus and concentration on the rider, rather than being distracted by anything that grabs his attention. This requires trust and confidence in the rider. Forcing the horse’s neck into a position whereby he cannot see is cruel. He will have some peripheral vision, but no binocular vision.

The horse’s range of binocular vision when jumping. In effect the horse looks down his nose, so his vision depends on the angle of his head. With his nose forwards, he can see further in front of himself to gauge where to land.

Submission and paying attention to the rider requires the horse to forfeit some of his visual information, becoming dependent on the rider to tell him where to go. This may explain resistance to the contact: if the rider is not very aware of what a ‘correct outline’ is, the horse may resist the contact. He may well be ‘tight through the back’ as a result of tension because he cannot see clearly, though there may be other potential factors such as poor riding, or ill-fitting tack, or physical pain in his body.

When a horse is ridden in an over-bent outline, his line of sight is towards his knees, limiting what he can see to the front.

Riding the horse correctly ‘in position’, or flexed to the inside, when riding in an arena, means to position the horse’s forehand so that the rider can just see the corner of the horse’s inside eye.

It is very important to be aware of your intention behind looking your horse in the eye. Staring him out would be intimidating – but useful if your horse is threatening, or testing you. Take your lead from the horse, and watch his eyes closely for clues.

Horse and rider vision – aerial view.

TIP

In my experience, I feel a better connection with my horse when we can both see each other; I am no longer in his blind spot, but he can see my face. If his head was straight, he would not be able to see me above the hips. I have found this very useful with a spooky horse; that visual connection was reassuring for him and gave him confidence. His whole body felt more relaxed when we kept eye contact.

EXAMPLE

I recall a ‘stare out’ situation with my Lusitano. He was about six years of age, and after a difference of opinion in a training session I had dismounted and sat on the mounting block contemplating my next move. He stood stock still, where I had got off him, staring me in the eyes, so I stared back. I wondered who would blink first. I held my gaze, and after a few moments, he lowered his eyes, and his demeanour became softer, not challenging. He walked towards me and looked at me with kind eyes. I did the same, mirroring the change in my own expression and body – I felt kindly towards him. I patted him, and I felt we had reached a deeper understanding in those few moments.

Hearing

The horse’s hearing

The horse is able to turn his ears to increase sound reception. On hearing a sound, the horse will do this in the direction of the sound to locate where it is coming from, determining whether it signifies danger and whether to run away from it. Horses can hear noise from low frequency to high frequency (14–25kHz) and have ten muscles in each ear, which can move the ears 180 degrees.

Horses have a highly developed sense of hearing and hear a similar range of tone to us. There is no need to shout at a horse: as mentioned, horses can hear low volume of sound, and are very responsive to tone of voice. In my experience, cracking a whip near a horse to urge him forwards causes tension, and they go faster from wanting to get away from the noise rather than learning the touch of a lash as an aid.

The rider’s hearing

Whereas a horse will turn his ears to amplify sounds, people turn their heads to increase sound reception. This relates to the facts that noise frequency range for humans is 20–20kHz and the human ear has just three muscles. Sounds we hear range from pleasurable to harsh and distinction can be made between the volume and pitch of sound. The sound of birds singing is easier on the ear than the roar of a motorbike passing in close proximity. In the stable, listening to the horse’s breathing for signs of abnormality, and hearing the noises he makes (snorting, chewing hay) are ways not only to assess health, but to sense a connection with the horse.