Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

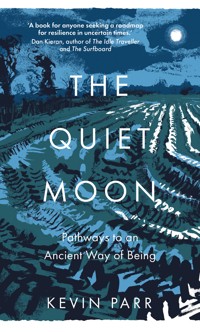

The ancient Celts lived by and worshipped the moon. While modern, digital life is often at odds with nature – rubbing against it rather than working in harmony with it – is there something to be said for embracing this ancient way of being and reconnecting to the moon's natural calendar? January's Quiet Moon reflects an air of melancholy, illuminating a midwinter of quiet menace; it was the time of the Dark Days for the ancient Celts, when the natural world balanced on a knife edge. By May, the Bright Moon brings happiness as time slows, mayflies cloud and elderflowers cascade. Nature approaches her peak during a summer of short nights and bright days – this was when the ancient Celts claimed their wives and celebrated Lugnasad. With the descent into winter comes the sadness of December's Cold Moon. Trees stand bare and creatures shiver their way to shelter as the Dark Days creep in once more and the cycle restarts. In The Quiet Moon, Kevin Parr discovers that a year of moons has much to teach us about how to live in the world that surrounds us – and how being more in tune to the rhythms of nature, even in the cold and dark, can help ease the suffering mind.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 416

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FORTHE QUIET MOON

‘[Kevin Parr] writes seamless prose like a moonlit weaver.’

Country Life Magazine

‘Kev Parr stands among the finest natural history writers of our generation … a masterful storyteller and a man wholly unafraid to bare his soul on the page. With him, the reader is blessed with the most thoughtful guide and companion.’

Will Millard, BBC presenter and authorof The Old Man and the Sand Eel

‘Lunar curiosity guides this graceful sharing, not only of Parr’s deep knowing of the natural world, but also his vulnerability as he wrestles with mental health. A beautifully personal book that’s bound by a sweet melancholy.’

Verity Sharp, broadcaster

‘Like its subject, The Quiet Moon is glistening, rich and strange … soulfully bewitching at every quarter, good company through every wax and wane.’

Tim Dee, broadcaster and authorof The Running Sky and Four Fields

‘A fascinating journey through myth, moonlight and ancient history.’

Chris Yates, author of Nightwalk

‘A powerfully honest and deeply reassuring exploration of an individual’s place in the world, and the incalculable wealth found when we take the time to notice the natural world and its rhythms.’

Fergus Collins, editor of BBC Countryfile Magazine

‘[Kevin Parr] is forging his own philosophy in his local landscape.’

Paul Cheney, Halfman, Halfbook

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

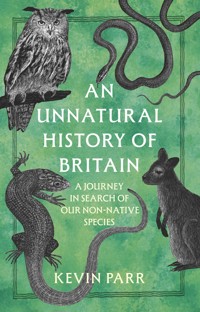

Kevin Parr is a writer, fisherman and naturalist. He is the author of the critically acclaimed Rivers Run (2016), which was longlisted for the inaugural Richard Jefferies Prize for Nature Writing. He is a columnist for BBC Countryfile Magazine and Fallon’s Angler, the angling correspondent for The Idler magazine and has also written for The Daily Telegraph and The Independent. Kevin lives in West Dorset with his wife and a colony of grass snakes a few strides from his garden gate.

To Zac, Millie, Ollie, Bertie, Erin, Bade and Rufus.

Cover image: Andy Lovell (andylovell.co.uk/)

Internal images: Sue Parr

First published 2023

This paperback edition first published 2024

FLINT is an imprint of The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.flintbooks.co.uk

© Kevin Parr, 2023, 2024

The right of Kevin Parr to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 290 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Prologue: A Glint of Moonlight

1 The Quiet Moon

2 The Moon of Ice

3 The Moon of Winds

4 The Growing Moon

5 The Bright Moon

6 The Moon of Horses

7 The Moon of Claiming

8 The Moon of Dispute

9 The Singing Moon

10 The Harvest Moon

11 The Moon of Smoke

12 The Cold Moon

Epilogue: The Blue Moon

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

PROLOGUE

A GLINT OF MOONLIGHT

The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk.

(Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Philosophy of Right)

THE SUN HANGS for a final moment. Bloodied like a bruised orange, but sharp-edged and spent. I can look straight at it, the dying ember of a flaming day. Its energy remains though. The still that surrounds me remains thick with the heat. Not a breath of wind, not even here where there is always a blow.

A bead of sweat drops from my eyebrow on to my cheek, smearing across the lens of my glasses as it falls. Suddenly I am aware of the damp around the neck roll of my T-shirt and the small of my back. ‘It’s good exercise,’ I remind myself, reaching for a tissue from my pocket to buff up my glasses. I’d almost swapped my shorts for long trousers before I left the cottage, but this evening is one of those fitful high-summer nights when the whole world has to stop.

There it goes. As it meets the horizon, so the liquid of the sun begins to ooze like the yolk of a perfectly poached egg. Smearing into the silhouette of Lewesdon Hill and then spilling in a lava bubble that sparks and fizzes and forces me to squint and blink my gaze away. A glorious sunset, although not as blazing as some. The haze and low cloud have diffused the dusk colours, softening the yellows and golds into mauve. It feels appropriate to the mood, though. The thick air that has plumed from the Sahara has brought a bout of brutal heat – even here in the West Dorset rolls where the fresh of the sea usually keeps the temperature in check. But I like it. I like the unusualness. The sun has all but set and I am feeling over-dressed in a T-shirt and shorts. There is a flavour of the Mediterranean in the air but with a serving of local seasonal vegetables. And the smell of this evening is the thing that I am finding most extraordinary.

Around my feet is a carpet of colour unlike anything I have seen on Eggardon Hill. There are harebells and bird’s-foot trefoil, red clover and lady’s bedstraw. There are thistles and grasses and a multitude of other plants that I cannot name. As I first stepped through the gate and on to the fort, and the perfume tickled my nostrils, I bent down among it all to try to find the actual source. There was no singularly distinctive waft, something powerful like a honeysuckle or lime, and none of the flowers or seeding grasses that I put my nose to seemed to have any great scent of their own. Instead, I was smelling everything – from the pollen and nectar down through the sun-warmed leaves and the exposed soil and desiccated sheep-shit. It is power in numbers. All of the most subtle odours teased by the heat and then allowed to simply hang. With no breeze or coolness to dissipate, I was probably even catching the whiff of the miniscule eggs that the marbled whites were scattering. All of these things coming together to create one glorious infusion. I was smelling the hill itself, the millennia of change in geology and ecology that had led to now. And even as I looked west at the setting sun, I couldn’t help but be distracted by the unexpected intensity that was provoking a different sense.

I hadn’t come up here to smell the air. I came alone but wanted to share the sunset. Or rather, I wanted to look at the sunset as others might once have done. The people who first took tools to the earth of this hill over 5,000 years ago, building ditches and ramparts, creating sanctuary in altitude, structure among the wild. What must they have thought to watch the sun disappear only to leave a trail of colour in its wake? Would they have cared? They would surely have stood as I do now, drawn unconsciously towards the fading warmth. Not least because of the connection with Lewesdon Hill and Pilsdon Pen that stand in the west. Both were topped with forts such as this one, as so many of the hills in Dorset are. Perhaps they would see the dance of flames from the homes of their counterparts. Fires lit to cook and communicate. A sense of visual connection they shared with the light of the sun itself.

I smile. I like the thought of standing where those people stood. At moments such as this I feel my own connection with them. An appreciation of a moment – this moment – and I don’t doubt that on an evening such as this they would have gathered together and simply watched. The world would have looked very different then, of course. And even as the hedgerows, field systems and electricity pylons dissolve into the dark, the lights of houses, the town of Bridport, a distant but arresting red-lighted mast, all remind me of the impact that humankind has had on the entire landscape. The wildlife would have been different too, but it is difficult to determine to what extent. There would have been some agriculture, but there were no pesticides, fungicides or combine harvesters. There was also but a fraction of the people. It is hard to visualise to what extent this part of Dorset would have been moulded by the hands of humans, when all around me today is managed.

The grass around my feet thrums with the chirrup of grasshoppers, while far below me, where the grass slips into a pocket of scrub and trees, comes the soft coo of wood pigeon. The colour of the trees grabs my interest – or rather, the lack of colour. If I move my eyes quickly across the tangle of treetops I can make out the green, but as I stare still so the colour vanishes in the lowering light and the shapes roll and swirl as my eyes try to fill in the gaps between what they know is there and what they can actually discern. The rods in my eyes stirring, only for the cones to dance as I look back up at the technicoloured horizon. There, the orange and gold of the sunset are already climbing higher and spreading. As the earth slowly turns so the sun finds more atmosphere to shine through. It has vanished from view and yet for a time it will brighten even more of the sky.

Dzzzzzz. What’s that? A faint insect buzz has quickly loudened and the source is now donking me on the head. I don’t recognise the sound. It isn’t a bee, wasp, hornet – a beetle perhaps? Ah! It’s a chafer. Not one of the big, fat May-bugs but a smaller summer cousin. It certainly seems to find me rather interesting, in particular the top of my head. There is no aggression to its behaviour but the sweat on my forehead is quite a draw, and a second chafer has now joined the first. Time to wander, perhaps. A slow mooch back around the southern slopes.

I glance back at the western sky, the mauves deepening near the horizon as the oranges lose their vibrance but stretch ever higher into the night. I still feel the pull – an urge to follow the colour and light. And the contrast as I turn away is marked. The eastern sky is deep blue and starless, the grasses and flowers of the ridge behind me all faded to grey. There is a sense of nothing about it, an emptiness that couldn’t contrast more sharply with the view west. But as I begin to tread a watchful path back, my route edges me out from beneath the loom of the inner rampart, and there, sharp and silent, is the moon.

It is surprisingly white, given the thickness of the air, although it is already quite high in the sky so has little atmosphere through which to yellow. I’m not sure quite when the moon will next be full, but it is waxing towards it, and judging by its size, is around four days away. The Moon of Claiming, a period apparently when the male Celts would venture out to ‘claim’ their wives. A primitive notion to say the least, although the more I learn about the people who would have built this hill fort, the more I question that sort of presumption. Perhaps I should rephrase that sentence – it is less the things I have learned and more the things I have unlearned. That touch of Roman propaganda that we have so long taken as read. And much as I, a white British man, have recently become aware of the way in which the history I have been taught has been delivered to suit my own demographic, so I realise that all history should be questioned to some degree.

More pertinent, though, is less what it represents and may have represented at this precise point of the year, and more how it reflects a pattern of process that I have subconsciously adopted. A month ago, the sun would have set to the right of Lewesdon, and in another month’s time it will be much further south, to the left of Pilsdon Pen. A natural calendar of sorts, although only precise if you line two points exactly together. The moon, on the other hand, will tell you the day no matter where it sits in the sky. A practised eye would recognise how far into the current quarter the moon has stretched: it would be almost as straightforward as flicking on a mobile phone or glancing at a wristwatch to check the date. And it wouldn’t matter that the moon is sometimes obscured by cloud because once you learn to trust your subconscious clock you soon realise how reliable it can be.

The key, though, is to allow yourself the opportunity not to care. It isn’t easy, much as if someone were to tell you to clear your mind of all thought and your head immediately floods with a sense of everything. To be able to lose yourself in a moment is only possible if you are able to not try to achieve that very thing. Rather like that moment when drifting off to sleep, when your thoughts start to drift sideways as your subconscious begins to whirr. As soon as you consider what is happening, you lift yourself straight back to wake.

Time is a harness because of our interpretation of its passing. Because we have to be somewhere or meet someone. Because we create goals for ourselves that relate to certain stages of our lives. Our expectations can be driven by human instinct; the pains that Sue, my wife, feels about us not being parents are compounded by a body in grief. The dreams I have where a child is mine, is ours, and yet is somehow out of my reach do not need Freudian analysis. And certainly I did not expect to nudge into my late 40s and find myself childless, renting a house and without savings. Wearing clothes with more holes than fabric and relying on my parents for grocery drops or help for when the starter motor on the car packs up.

Sometimes we are forced to walk paths that we don’t want to take, yet there remain the assumptions of what will come. Fifteen years ago, after a fairly carefree meander, the pieces had pretty much slotted in place. A mortgage on a new build, enough income to be putting several hundred pounds away each month. The future was ours to make and at a pace of our choosing. Even when the threads began to unravel there was no immediate panic. Sue would get better; I would write a best-seller. Selling up was a short-term necessity but it was short term. And there were always going to be children at some point; that was something so inevitable that it didn’t need to be discussed. Which then, of course, makes it all the more painful when reality finally rattles at the door. Time catches up with us all.

The compulsion that found me on Eggardon Hill this evening is linked to all of those things. But only because I saw the date and associated it with a ten-year anniversary. It is a decade since we moved to Dorset and that caught me a little off guard. To the extent that I created my very own tumult. A whirl of regret, shame and disappointment. I was a 13-year-old boy again, falsely believing that school marks were all my parents and teachers cared about. And then came the glorious grounding. The smell and the sunset. A reassurance of all that we do have – and that is plenty.

I walk a few steps and then pause again, looking once more upon the moon. As I do, my eyes catch a movement of light further away and below the horizon. A double-decker bus, probably a late-running Jurassic Coast Special, is trundling westward along the A35, around 2 miles away. I can hear the faint hum of the road when I listen for it, but I had detached from it in order to let the grasshoppers and chafers flood my ears. There I was, a moment before, perhaps not quite imagining myself as an ancient Celt, but certainly feeling some sort of connection to that time. Seeing the moon and perhaps sharing a similar understanding as to the concept of time. And, there in the distance, a reminder of today. Of modern life. Two rows of bus windows lit up and moving at speed. It is far too distant to determine if anyone is behind those windows, but rather like a train passing at night, I have a snapshot into another world lived at a different pace and no one there knows that I am here watching. It reminds me a little of standing on a bridge and looking into a stream below. The constant yet ever-changing movement of water that is on such a different course to my own. Two paths cross but do not, and cannot, mingle in that moment. So separate are they of purpose.

I reach down to feel the damp of the grass but it is slight. The heat and dusty air holding back the dew. Still I tread carefully as I make my way down the southern slope, aware that even a light moistening could make for greasy footfall, and as I do I notice my shadow. The moon is bright enough and high enough in the blackness to cast my form and in a moment my presence seems more tangible. As I had slipped out of my own mental constraints, so I had become less aware of my physical being. Now, though, my moonlit shadow moves slowly with me, reminding me of myself. And that self is so much more content than it had been when I arrived. The anxieties and self-deprecation melting into the mauve. All it took was for me to step sideways for a moment and to forget how long a moment should actually be. It doesn’t matter how old I am, or what I haven’t got or achieved. I am gloriously insignificant. Almost as though coming here tonight on a different pretence was actually my subconscious pulling together the things that I needed to ground again. To step away from Time.

I have learned a lot this year and hope to continue to do so. But perhaps the most important lesson is here right now. It is high summer, but in a couple of pages’ time I will take you back to the cold and dark of midwinter, because that is where we always start. But the sun doesn’t rise as the clocks strike twelve on New Year’s Eve and nor does the moon sit full. The cycles are ongoing, regardless of how much we try to shepherd them. Sometimes we need to break our own rules and routine to remind ourselves of that. After all, the Celts didn’t begin their year with fireworks and Auld Lang Syne, if they even began a year at all.

And that is why I can write an introduction to a book that is already halfway written. It’s just taken me six lunar cycles to realise the fact.

1

THE QUIET MOON

An absolute silence leads to sadness. It offers an image of death.

(Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Reveries of the Solitary Walker)

IT’S GREY AND STILL, one of those winter days when the world forgets to wake up. There have been moments when the sun has threatened an appearance, but the blanket of cloud has remained, the temperature barely shifting from night into day. These are the sorts of conditions that the angler within me longs for at this time of year – mild air and low light levels can make for excellent fishing. But my rods are at home and my body and mind need a different kind of interaction.

Daily exercise had felt more achievable last March when we first went into lockdown. Helped no doubt by a sense of novelty about the situation, but likely too because spring was gaining some momentum and bringing so much possibility to the world. I also had a heightened appreciation of the place where we live. Stepping straight out into a landscape that millions of other people could only dream of as they stared on to concrete from the prison of their own circumstance. I was encouraged to exploit it because I felt such privilege; to not make the most of living in rural isolation would have almost been insulting to those who would have wished to be. And we were all in it together – there was, in the beginning at least, a sense of togetherness as the whole world came to terms with a shared threat. We thought of those living alone and the less able. Those stuck in high rises or separated from loved ones. And we shared what we could – photographs, podcasts, little snippets of birdsong. We Zoomed and quizzed and shared virtual pots of tea. And all the while, the days were lengthening, spring would lead into summer and all would be well.

The circular walk around our own little patch of West Dorset, which I might usually make once a fortnight, became a daily stomp. There was, admittedly, a lengthy pause halfway to scan through the mixed flock of buntings that had settled in number in the stubble and maybe snatch a glimpse of the merlin that shadowed their winter. But I began to lose weight, to breathe deep and almost – almost – feel a bit better about myself.

Ten months on, though, and I have slipped back into familiar habits. The hangover from a cancelled Christmas and New Year has been tempered by a continuation of excess. The weekends well wetted with cheap cider, while a glut of carbohydrates replaces the alcohol during the week. The house is cold, my afternoon naps are increasingly difficult to wake from and I’m finding too many excuses to avoid any kind of physical exertion. And while I know what is good for me, what will actually make me feel sharper and happier, the lack of motivation is coupled with a depressive cycle that has whirred for most of my life. There comes a point when won’t becomes can’t, and sometimes can’t actually feels like a curious sanctuary.

Today, though, I was prompted out for a purpose not my own. A visit to my parents’ house to help out with a few urgent chores around the garden. It is always easier to nudge myself out if it feels as though I am obliged for someone else’s benefit, a state of mind that will in turn be beneficial for me. The road to Beaminster (where my parents live) is a lovely one, dotted with places to stop on my way home for my daily exercise. I chose this spot because I don’t know it very well. It is close to one of my autumn mushroom haunts, where a mossy roadside verge can sparkle with chanterelles. I first stumbled upon it several years ago when exploring some of the quieter lanes of this already quiet area. Taking ever more varied routes from home to the weekly supermarket visit in Bridport, windows down and the car doing a very lazy trundle. I was slipping through a thick beech corridor when a spill of gold caught my eye. A lovely clamber of chanterelles glowing against the green like the first celandines of spring. I was a little bit too excited, though, and didn’t consider how deep the mud was in the spot where I pulled over. The nearside wheels sank and the car bottomed out, leaving me marooned and with barely any battery on my phone to call for aid. The tranquillity of that little lane leaving me feeling rather isolated. It took a kindly soul in a Land Rover to drag me back on to the road, and I later delivered a basketful of chanterelles to his door as a thank you.

Visits here have since been fleeting. A quick, early-autumn diversion to check the mushroom spots before journeying on elsewhere. A couple of years ago, though, I came on a whim. It was later in the year and winter was already nibbling at autumn’s toes. The beeches had gone to brown and I didn’t loiter long beneath them. Instead I pushed through the trees and picked up a footpath that I had seen marked on the Ordnance Survey map. The local slopes and pasture are crisscrossed with public rights of way, and the majority seem never to be trodden. Often it is a case of picking out the footpath signs and forming your own route between them, and, providing the gates are left as they are found and respect is given, there is nothing but a cheery wave should a farmer or landowner appear. On that day, having followed the path I had seen on the map for a time, I picked up another route and trod into open country where I discovered a meadow filled with waxcaps. The dew had added an extra sheen to their glisten and even the white snowy waxcaps had a sugary shine like polished marble. The sight of those fungi had elevated my walk and given me cause to return. Today might be too late in the season to see any mushrooms but I am curious as to what else I might stumble upon. The one issue being my own state of mind. I am not feeling particularly open to opportunity and have a niggle that is urging me to return home and draw the curtains. The hour is already late, so what is the point in lingering?

I take a deep breath and press on to the gate that leads me out into the open country, pepping myself up with each step. There might be a barn owl hunting, or even a hen harrier. I might see a hare or even a wild boar. Come on Kev, at worst you are getting your heart thumping and stretching your legs.

I pause in the waxcap meadow, beginning to begrudgingly feel the benefit of my push. There is nothing but pasture around my feet, the grasses looking tired and yellowed. Dying back in the cold, rather than gnawed by sheep or cattle. A short effort takes me up on to the summit of a knoll, where a single gorse stands leggy and slightly bare. In the south-west there is a slight hint of a glow. A narrow smear of orange-pink that sits like a letterbox at the foot of a great dark door. As I watch, it smudges back behind the grey of the cloud, but that was the first hint of the sun that I have seen for a couple of days. It also suggests that the hour is slightly later than I thought, and I turn to the south-east, expecting to see the moon. I smile at my absent-mindedness. If the sun was unable to poke a route through the cotton-wool veil of cloud then the moon certainly wouldn’t be visible. It would be there about now though. I had noticed it quite high in the sky at dusk two days ago, just before the cloud rolled in, so it should still be rising in the daylight. Instead, though, my attention is drawn to another familiar form. Eggardon Hill looks a little disappointing from this angle. My own elevation and the sweep of the rise to my left have allowed it to meld into a landscape it often dominates. The ridged ramparts of the Iron Age hill fort that sits atop it are distinctive, however, and take my thoughts in a different direction.

I remember as a child visiting the Bosworth battlefield. I was around the age of 10, and my family were staying with friends, my godfather’s family, in Leicestershire. I knew nothing of the history involved, or the relevance to what little history I knew, but was intrigued as to what I might see. As it turned out, I was wholly underwhelmed. All I was looking at were fields and hedgerows, through the muck of a damp and blustery day. I have no idea what I expected to witness, but given the build-up, the talk of civil war and the death in action of Richard III, I certainly didn’t anticipate a view little different to those I saw back at home in Hampshire.

In hindsight, I am quite surprised by my response. My imagination has always been quite easy to rouse, and I had a nervous anticipation of what I might see or how I might feel. Yet I found it difficult to visualise anything beneath the surface. I felt no connection. It could be that I was unerringly tapping into the dispute around the actual battlefield location, but far more likely was the fact that with no remnant of that time, I couldn’t fill in the gaps. And having grown up in a heavily managed, if rural, area, I had got used to a landscape without historical context.

The folds of West Dorset are less sanitised, largely because the clefts and combes that have formed across this melting pot of geology are less convenient for arable agriculture – proven, perhaps, by the lynchets that remain stepped into the hillsides. Earthworks created by ancient humankind in an effort to exploit every inch of available soil, now regarded as nothing more than grazing pasture. With less pressure on the land, there remains a greater sense of what once was, and there are also far more clues to the past. Alongside the lynchets are hill forts, tumuli, stone circles and sarsens. Most of these are untouched, like the stone burial chamber around half a mile from our cottage. It appears to be partially collapsed but I have found no record of it ever having been officially opened or excavated. And every year the farmer ploughs around it and the crops grow almost high enough to hide away the stones.

As I walk around such places, invariably with a primary interest in the wildlife rather than the historical context, I cannot help but feel a sociological connection to the land. I am less drawn to the actual history and process than to an empathy with the people who once lived here. It is loose, of course, but tangible, and stems from a decade of living outside the perimeters in which I – we – had always expected to live. We sold our flat in Winchester while we still had some equity to call our own. Illness had forced Sue into redundancy and that meant our income more than halved. A move west had always been mooted, to find a spot midway between our families, but it came under slightly forced circumstances. Not that we minded too much. It was an adventure, of sorts, and certainly a chance for me to tread a different path. But we live in a society that doesn’t much care for those on the fringes. When you step out of the flow, whether by choice or from being pushed, it is very difficult to get back in the water. And there comes a point where you begin to realise that there are more important things than getting your feet wet. The rhythm shifts. There is a different perspective.

It is no great surprise to feel a sense of warmth from Eggardon while on a walk I’d frankly rather not be on. It is like seeing a familiar face, a reminder of our home just to the east and the security that comes with that. And it is impossible to look at Eggardon and spend time walking the ramparts and ditches and not imagine it as it once was. Aside from the physical reminders that set it apart from a potential battlefield site in Leicestershire is a deeper, ingrained sense of purpose. I will visit to catch a glimpse of the first wheatear of my spring, or to search for the almost unworldly iridescence of an Adonis blue butterfly in the late-summer sunshine, but there are moments when my mind drifts with a people I know little of. Over time, that sense of connection has spread into the wider area, and I find myself wondering if the sense of escape that I seek in moments of need is similar to the deeper immersion that the Celts must have had within the world. I like to think that they felt themselves part of the landscape and not masters of it. A sense of harmony that reached beyond the land that provided food and shelter and into the sky from where they might have drawn a sense of time.

With no religious or Roman influence, it seems likely that the ancient Celts based their calendar around the lunar cycle. I say ‘likely’ because there is much we don’t know about Celtic life and much that we have previously accepted through the eyes of others. Fake news is not a twenty-first-century phenomenon, although the modern interpretation where facts can be dismissed as such because they don’t suit personal agenda perhaps is. But history is always read from a singular perspective which in turn reflects popular culture. Much of what we ‘know’ today about Richard III, who fell at Bosworth, might be spawned through modern interpretations of William Shakespeare’s portrayal. Shakespeare was unlikely to present favourably the man who stood as enemy to Henry VII, particularly while the House of Tudor still ruled, but such depictions become so often repeated that they are accepted as fact. It is a situation even more common in the internet age. As remarkable and accessible as the internet can be to research just about any subject you choose, there is no governance or control over content. Copy writing (and I speak from experience) is often a case of simply finding a relevant source and regurgitating the words in a manner that appears different. A false fact can be innocently, if lazily, repeated and over time it will become more established than the truth itself. Propaganda is ever easier to distribute and individuals ever more easily influenced. And, as a result, any one of us can filter out anything we disagree with and find someone else who shares a specific view.

It is a pattern highlighted by Michael Holding when speaking in relation to sports people taking the knee to highlight racism: ‘History is written by the conqueror, not those who are conquered. History is written by the people who do the harm, not by the people who are harmed. We need to go back and teach both sides of history.’

The Celts were a people who made no written record of themselves. Instead, history has portrayed them through the writings of others, chiefly those who were their enemies. Roman and Greek scribes were not often complimentary in their descriptions, presenting the Celts as barbarians, primitive and warlike. Aristotle believed them to be a people ferocious and fearless to the point of irrationality, while Julius Caesar wrote of them as squabbling and aggressively partite, the antithesis of Roman civility. It would seem easy to disregard such information and instead draw only from archaeological evidence, but author and professor Barry Cunliffe counsels against this in The Ancient Celts, suggesting that ‘to reject such a rich vein of anecdote would be defeatist: it would admit to an inability to treat the sources critically’. Wise words. As always, the answers are somewhere in the grey of the between.

My own readings of Celtic history have come from a somewhat niche interest. Sue and I were sitting one evening, lights off and the curtains drawn, watching the moon rise behind the ridge to the south-east of our cottage. There had been a fair bit of media chat about this particular ‘supermoon’, and though I can’t recall exactly what it was being called, I do remember puzzling over its origins. It was a beaver moon or sturgeon moon or something that didn’t have an obvious connection to the folklore of the British Isles. I was reminded of the term ‘Indian summer’, often quoted when we enjoy a spell of settled, sunny weather in the traditional meteorological autumn. For a long time I had falsely believed it to be attributed to the short dusks and heavy dews familiar on the subcontinent, rather than a provenance possibly inspired by Native American culture. It transpired that the names for the full moons were similarly sourced, a reflection of the cultural influence that the New World has had in Britain, and elsewhere in Europe, for several centuries. I found it odd at first. Surely the moon held greater significance to the ancient cultures that once lived here? And yet, it made complete sense. Nothing was written before the Romans arrived so there was simply nothing recorded. And a delve into the chaos of the internet took me deep into a rabbit warren where every tunnel seemed to bring me back to the surface. I could find plenty of patterns, plenty of lists, but the common theme between them, aside from the names of the moons themselves, was the lack of a source. It became a mild obsession, fuelled every twenty-eight days when the moon filled once more and my sleep became fitful. I would invariably follow the same fibreoptic paths and end up at a similarly blank conclusion. Whole days were spent orbiting a subject that had nothing to do with what I should have been doing, until I realised that I was overlooking a rather vital aspect. I was looking for a nice, neat list of twelve names. One for each moon and twelve for the year. Except, of course, that a year is measured by the length of time it takes the earth to orbit the sun. The moon has no involvement in that. So I was effectively looking for something that couldn’t exist. This realisation left me with a couple of thoughts. Firstly, this was all getting beyond the capabilities of my mind and my head was beginning to hurt. And secondly, aided no doubt by the first point, how much did it really matter?

I’ve changed direction, heading north to skirt around the next knoll and then aiming for a gateway where I can pick up the road and have an easy stroll back to the car. I had planned to follow a route down the main slope of pasture and scrub to where the land suddenly buffers and forms a wide, flat area. I stumbled upon it on my previous visit and almost lost a welly as I squelched into the edge. There was a small area of standing water on one side, thick with alder, but probably not a permanent pond. I unwittingly spooked a couple of mallards who poked their way out through the trailing branches and quacked into panicked flight. I watched them circle a couple of times, assured them I wouldn’t disturb them any further, and then worked back up on to more solid ground. As I looked back at the chive-green clumps of club-rush, I wondered what might be tucked up out of sight. Snipe were an obvious possibility, hunkered down with long beaks lowered. Eyes aware but stock-still in mottled brown. It was the possible glimpse of a snipe that had led me back in the same direction, but guilt and apathy have combined to prompt this change of course. While I don’t need much persuading in this mindset, on this occasion it seems more than reasonable. Snipe are birds rarely seen in these parts unless flushed, and it doesn’t seem fair to do so just for the satisfaction I will get from that flash of zigzag flight.

There is a spot closer to home which is reliable for adders but is also a winter haunt for snipe. It is clay-clogged and boggy, and not where you might expect to find reptiles, but here and there are small, solid, brambled islands where the adders find drier ground. One spot offers an almost guaranteed sighting on a sunny mid-February day, but it is impossible to reach without startling a snipe or two, and in recent winters I have not had the heart to look at all. Leave them be, if they are there, and enjoy an encounter that is altogether unexpected. Especially if it means I can go back to the car, go home and find my own patch of rushes to bury myself in.

I climb the gate rather than open it, a habit that has formed in less than a year. Being closed off from a world suddenly obsessed with sanitisation can create some interesting new obstacles when you do venture out. The latch of a gate – who might have touched it and how long ago? Perhaps a wipe with a tissue will make it safe or working the mechanism through the sleeve of my coat. Is this verging on hysteria? Perhaps if I vault the gate then I can negate the whole issue. It is curious how quickly quirks in behaviour become the norm during a pandemic, although I do climb my gates with care. I once managed to break the bottom rung of a wooden fence with a slightly heavy-footed clomp. I was able to prop it up but had a guilt-filled night and returned the next day with a hammer and splice to make a better repair.

The unforgiving tarmac is not a pleasant surface to walk upon, especially in cheap wellingtons, but the route back to the car is a steady climb that I can push along and get my heart pumping. A compromise to my inner critic for cutting my walk short. As I reach the trees, the air thickens a touch and I catch the waft of pine. Just a hint, not enough to sink into and lose myself in, but it should sharpen as I curve into the main body of forest where the conifers outnumber the beech and hazel. As the lane begins to turn, though, it is another smell that hits me and I break stride in response. The musk of fox hangs heavy, and I slow my breaths to avoid too deep an inhalation. It is a pungent, sulphurous odour that seems to intensify when it gets inadvertently trodden into a carpet or rolled deep into the matted fur of a pet dog. It seems less offensive outside though, when tempered by the damp air, and the slight floral edge can make it mildly evocative. The scent is supposedly comparable to that of a violet, and the supracaudal gland that produces it is often named accordingly. Other mammals, including dogs and badgers, have a similar gland, but the sweetness seems to be especially distinctive to foxes.

I glance around, half expecting to see the animal itself, but sights of foxes are normally fleeting and distant. An after-dark drive around the lanes might offer a glimpse in the headlights and the bitches bolden when they have a den of hungry cubs to feed, but the fox is a mammal more often heard than seen. Especially in January.

A fox courtship is a short, intense love affair. The vixen is in season for a matter of days and throughout the preceding fortnight her beau will not leave her side. They will hunt together, sleep together and mate frequently in order to ensure fertilisation occurs during that most brief of oestrus cycles. The act of copulation might appear painful, and many people believe it is that moment when the vixen cries her pained torment. Others, though, believe that she screams in order to attract a suitor and make herself known, while further study has suggested that both the dog and vixen produce the wail perhaps as a declaration of amour. Whatever the precise reasoning, there are many of us who have sat bolt upright in bed having been shocked awake by a scream that is truly blood-curdling.

The eighteenth-century French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc likened the sound to that of a peacock, but it can be both otherworldly and eerily human as it slices through an otherwise silent winter night.

Humankind has long had an uneasy relationship with the fox. We have persecuted him for stealing hens and raiding pheasant pens and yet we encourage him by occasionally leaving the coop door open and releasing millions of part-domesticated game birds every year. We leave rubbish bags in the street and we drop litter by the ton but we bemoan the foxes for making meals of our waste.

So affected is he by human influence that the urban fox has evolved with very different characteristics from his rural brother. He is bold and fearless, and happily diurnal. His bright red fur and thickset brush have become grey and spindly as he trots through dusty pavements and leaps garden fences. I have watched an adult fox slink down Richmond High Street on a warm summer afternoon. He was utterly unfazed by the crowds of shoppers and interestingly no one seemed to notice him. Perhaps in the eyes of some he had simply become another homeless person on the street, ignored, as many are, to the point of invisibility.

In his more traditional habitat, the fox is still considered by many as vermin and he maintains a low profile as a result. He is nervy, still hunts as much as he scavenges, and keeps less sociable hours. Daylight glimpses are less usual and give the impression of an animal far scarcer than he actually is. But there is a fascination to be found in observing a truly rural fox. An unexpected encounter still delivers a shot of adrenaline. He is, after all, a hunter and natural competitor. And although he will run, we will always watch him out of sight, as if he is likely to creep back behind us and play a nasty trick when we are not looking.

Humankind has long tagged the fox as a creature of cunning who is not to be trusted. In ancient Greece, Aesop wrote many of his fables with a fox as a central character. The fox is portrayed as a clever animal, certainly when he outwits the sick lion, but also as one who charms for his own benefit and who can dish plenty out but not be so happy to take it. Aesop seems to regard the fox with a grudging respect but ensures he always gets his comeuppance.

The image of a sly, cunning trickster is a moniker that the fox wears to this day. In medieval Europe the character of Reynard the Fox evolved, sparking adaptations within French, Dutch and German folklore. In each culture Reynard was anthropomorphic and always seemed to walk the less respected paths of society. Geoffrey Chaucer penned his own nod to Reynard in one of his Canterbury Tales of the 1390s. There is some mystery to the true origin of the storyline, but The Nun’s Priest’s Tale tells the story of Chauntecleer, a cock whose crowing was unequalled throughout the land.

Chauntecleer dreams of his own demise at the hands of a fox, the same animal that had previously tricked his mother and father. Despite his wife’s assurances to the contrary, the dream does indeed come true and Chauntecleer comes face to face with his subconscious tormentor. The fox is wily and charms the cock into crowing, at which point his eyes are shut and he is easy to grab. With most of the farmyard in hot pursuit, Chauntecleer then displays cunning of his own and persuades the fox to stop running in order to taunt the chasing throng. The fox does so, but as soon as he opens his mouth, Chauntecleer flies out and finds refuge in the branches of a tree.

Chaucer’s tale reflects humankind’s need to humanise animals. The fox is portrayed as a devious crook who, while using his charm to his gain, is also prone to losing his gain to his vanity. In truth, the fox does not kill every hen in the coop through uncontrollable blood lust; instead he has found a food source that if safely cached could last many months.

The fox is reliant on his larders through the cold of winter. Items of food, such as Chauntecleer’s unfortunate parents, would be buried and stashed ready for recovery when pickings become lean. The cold air and part-frozen soil slows the deterioration of cached food, ensuring that during a lengthy freeze there may still be scraps to be found.

There is no sign of a big freeze this winter. Not yet at least. And in many ways a crisp, cold but bright day would be preferable to the dull grey that we have been having. It would certainly give a useful boost to my serotonin levels. What is curious, though, is the quiet. I have reached the car and paused and there is very little going on. The woodland here is rich, with mature beech and plenty of understorey species. Fallen limbs are left where they lie and the moss on the banks looks deep enough to sleep on. Yet the air is as silent as it is still. I wouldn’t expect much birdsong, although I have heard mistle and song thrushes tuning up elsewhere, but there should be a business of tits, treecreepers and goldcrests that isn’t there. No rustle from a grey squirrel, no seep from bullfinch. Ah, but there is a nuthatch, somewhere in the canopy overhead. The steady plink as it slinks around the branches rather than the hurried bubble of its main call. And now the spiralling notes of a goldcrest. A little way off, too far to pinpoint, but unmistakable nevertheless.

The quiet is appropriate, though. To now. Energy is precious in winter, survival often a daily tiptoe along the edge of a knife. This is no time to be squabbling or exploring or wasting a single scrap. It might be easily overlooked from the inside of double-glazed glass and cavity wall insulation, the tweak of a thermostat more convenient than putting on a jumper. But a cold snap will still take its toll, on the homeless and elderly, those watching every single penny. These were the Dark Days, a critical time for the Celtic people. A period peppered with disease, famine and death. Fresh food was scarce, with the ground offering little in the way of sustenance. Meat could be sought, but with little light in which to venture, and harsh, cold weather, hunting carried ever greater risk. This was a time when darkness was something to be truly feared; nights were best left to the wolves and bears. A slip or trip could cost you more than a sprained ankle or fractured bone. And the quiet itself would have carried an eerie menace. Anything breaking it could carry direct threat, from something or someone desperate.

I ponder Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s words taken from The Reveries of the Solitary Walker:

An absolute silence leads to sadness. It offers an image of death.