Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

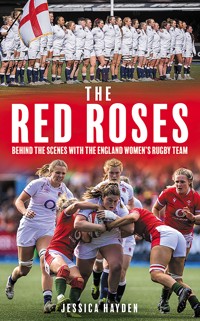

Shortlisted for the Charles Tyrwhitt Rugby Book of the Year 2025 Go behind the scenes with the winners of the 2025 Women's Rugby World Cup. In January 2019, England's Red Roses became the first fully professional women's rugby team in the world – their abiding mission being to win back the Rugby World Cup. After their narrow defeat against New Zealand in 2017, the formidable squad developed a hugely successful game plan that earned them the longest winning streak in rugby union history. Acclaimed sports journalist Jessica Hayden, who has had unprecedented access to the Red Roses during the writing of this book, goes behind the scenes to follow their challenges, heartbreaks and triumphs. Featuring interviews with all the major players, including Marlie Packer, Jess Breach, Emily Scarratt and many more, this is a truly inspirational story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 354

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE RED ROSES

First published in 2024 by

Arena Sport, an imprint of

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Jessica Hayden 2024

The right of Jessica Hayden to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78885 688 1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

This book is dedicated to every Red Rose, former and present, who put their bodies on the line for their country and led the way for today’s crop of Red Roses. It’s also dedicated to the female organisers and administrators who faced mammoth challenges and opposition in the early days of international women’s rugby and did it anyway.

When women work together, we achieve incredible things. Thank you.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. The pioneers

2. Growing Roses

3. It takes a certain kind of woman

4. A holistic vision of success

5. More than a maul

6. The 2021 Rugby World Cup

7. The road to rebuilding

8. Roadblocks to success

9. Building a legacy

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I had no introduction to rugby until I went to Swansea University, where I studied politics. I wanted to join the football team and went to the freshers’ fair with my heart set on being a central midfielder. The football coach was on his phone and didn’t stop texting to answer my questions about joining. Feeling quite downtrodden, I carried on wandering around the fair and saw a girl with a can of cider in her hand, pouring it all over her face. She was doing a straight-arm pint, or something like that. She had to try and drink her cider without bending her elbow. I could see her bruised legs and could hear her team-mates clapping her on. Whatever club she was in, I wanted to join. I walked over and introduced myself and she gave me a sip of her cider. She told me her name was Clara and she played rugby for the university. I signed up instantly.

I went along to my first training session and there was Siwan Lillicrap, who later went on to become the Wales captain. At the time she was the director of rugby at Swansea University and my first impression of her was that she was bloody scary. Her thick Swansea accent was made harder to understand because she seemed to shout everything. I was relieved when another coach said, ‘You’re with me, mush.’ The coach was Sam Cook, or Cookie, as I knew him. I had turned up in a South Africa rugby jersey which had been a birthday present (only because I was in South Africa for my birthday, not because of any real interest in rugby), and Cookie had seen that and assumed I was therefore a rugby player. He demonstrated a gentle tackle on me, walking through the stages of placing cheek to bum cheek, wrapping arms and putting the player on the floor. I remember thinking I needed to keep a strong face and pretend it didn’t hurt. At the end of the session, Cookie asked me if I would like to play in the ‘Old Girls’ fixture on the Wednesday, two days on from that first training session. Like any good fresher keen to look a lot braver than they really are, I said yes, unaware that I had just signed up to play a full-contact rugby match against players including Siwan. Off to Sports Direct I went, ready to spend as little of my student loan as possible on a pair of rugby boots and a gum shield.

I didn’t make a single tackle or pass the ball once. Well, that stretches the truth a bit. There was one pass I made, but it’s not a story I’m too proud of. Someone, for some unknown reason, passed me the ball and running towards me came Siwan. In that split second I had three choices: try and take this ball into contact (with no idea about how to present the ball), turn back and run away from Siwan, or stand still and piss my pants. In the end I just handed the ball to Siwan so she wouldn’t tackle me. My rugby skills have improved only marginally since then.

As the years progressed, I made some wonderful friends who are the most fun people in my life. Clara turned out to be the best influence on me because she dragged me out of my shell and forced me to face my fears all the time. She made me braver and more able to stand up for myself. I also met two of my closest friends, Monique Latty and Angelika Jankowska, thanks to our days playing rugby at Swansea Uni. Joining rugby often made me behave terribly, broke my bones and gave me the ability to funnel a pint in under ten seconds. But most importantly, it gave me the most incredible friends. I go to rugby matches and bump into girls I used to play rugby with, I present events and spot faces in the crowd whom I once shared a huddle with. Women’s rugby is a community of women who will challenge you, get the best out of you and party with you afterwards. When women work together, we achieve incredible things. There is no group or setting I have been in that is quite like those days of playing university women’s rugby.

It gave me other things too, not least of which is my partner Nick, who coached women’s rugby at Swansea University. He would probably sue me if I don’t mention that he never coached me, but he was one of the coaches (don’t blame me for dating one of the coaches, I watched Bend It Like Beckham growing up . . .). Anything tactical about rugby in this book, or anything I write, tends to be sense-checked by him. He was the first man I knew who was truly committed to women’s rugby. He coached the Swansea Women (known as ‘The Whites’), who were the best Premiership team in Wales for years, and self-funded his trip to the 2017 Women’s Rugby World Cup to support the players out there whom he coached at club level. People often say how lucky I am to have a partner who understands my world so well, but he was in this world long before me. And really, I had to pick someone who loved women’s rugby or else I would have nothing to talk about. Women’s rugby really is my entire personality.

But the most important thing that rugby gave me in those early days was my career. I studied politics at Swansea and tried to write every essay about feminism. I love learning about women’s rights, and to this day whenever I type ‘women’s rugby’ on my phone, autocorrect asks me if I mean ‘women’s rights’. Can you sense yet, reader, how utterly obsessed I am with women misbehaving? For me, women’s rugby was a gateway into a world of women who were pushing against the status quo, working really hard, and frankly, looked like me. In my third year, now friends with Siwan and no longer completely terrified, I had a conversation with her about her week. She had a full-time job as director of rugby at Swansea University, but also played for Swansea Whites, Ospreys and Wales. Every single day of her week, from the early morning to the late evening, was spent either coaching or playing rugby. She was remarkable. It made me wonder if rugby fans realised the sacrifices women make to play international rugby.

I knew I wanted to be a journalist and had sort of expected to go into political journalism when I graduated. I had no contacts in the field but I had been writing for political blogs since I was 15, under a male alias, and had even been in a Channel 4 documentary about my feminist activism. By the time I was at university I had been invited to the House of Commons to speak about sexism in the media and how it affected young girls. At age 16 I had been on ITV’s This Morning to speak about wanting to get rid of page three (for those unfamiliar, some national newspapers used to have boobs where there should be news on page three). I had no fear of speaking out and when Siwan told me about her week, I felt like my love for rugby could be used to do good, and I started a plan to become a women’s rugby journalist.

I applied for work experience at The Times and feigned interest for a week at The Sunday Times Magazine while slowly walking past the sports desk every day until I eventually mustered up the courage to introduce myself. I secured a week of work experience there, during the Six Nations. In that week, a male journalist at the paper had written a piece suggesting that the Women’s Six Nations should be moved to Wednesday nights so that the matches didn’t clash with the men’s Six Nations and therefore more fans watched. Did he not realise they had jobs? I pitched an idea to write about the sacrifices international women’s rugby players make, spoke to players from Wales and Ireland – including Doctor Claire Molloy who played for Ireland at the time – and in the paper it went. The sports desk was impressed and asked me to stay on for another week. I wrote even more, and it was the start of my career, which now sees me write about women’s rugby, present matches and talk about it on the radio and TV. For me, it is the greatest job in the world.

Writing this book has been a labour of the purest love. I adore women’s rugby. I love the players, the people and the stories. Women’s rugby is so much a part of me that I’m not sure if there’s much else left. Thank you for supporting me, by buying this book, and letting me write so much about it.

I want to say thank you to everyone who spoke to me for this book, both on the record and off, with particular thanks to Marlie Packer, Jess Breach, Emily Scarratt, Maud Muir and Abbie Ward for their support.

And last but certainly not least: a heartfelt thank you to my family and friends. Writing a book is incredibly selfish. I have lost count of the plans I have had to cancel in order to write this book while working full-time for The Times. It has been an incredibly busy time. My partner Nick has been a great support, as have my parents Tracy and Neil, my twin brother Mark, my two remaining grandparents: Nana Chris and Nanny Pam, and my extended family, with special mention to my uncle Gareth, who have all bravely asked, ‘How’s the book going?’, and even more bravely, stuck around for the answer.

I would like to finish with a final acknowledgement to my Grandad Den, whose portrait sits proudly on my desk as I type this sentence, and as I have typed this entire book. In the photo his tie is skew-whiff, he has my mum’s red sun hat on, and he has a cigarette balancing between his lips. It was taken after a particularly good night out, I am told. He was the most incredibly funny man, whom I loved and cared for deeply. He really didn’t like women’s rugby, or more specifically, he really didn’t like me playing women’s rugby, but he kept a collection of my published work next to him in his chair and I know he would have been so proud of me for writing this book.

INTRODUCTION

The bitter taste of an unattained pinnacle hung in the air as the England women’s rugby team stood still, hands on hips, taking in deep breaths of cool air in Eden Park stadium. They could barely move, almost frozen in time, as they watched New Zealand celebrate wildly only metres away from the try line where the Red Roses had gathered, crestfallen. The New Zealand crowd roared, lights flashed, and the sound system blared out celebratory music, but for the England team, there was only silence.

The Red Roses watched the world move on without them. Every minute felt like an hour as the players’ eyes stung and their lungs burned with anguish for the game just lost, slowly processing what had just happened. Their bodies were worn out from a long tournament and their hearts were shattered. The weight of expectation and the relentless pursuit of glory converged into a single devastating moment of realisation. They had lost the World Cup final, again. It was a reminder that in the arena of sport, victory and defeat are inextricably entwined, each lending meaning to the other, juxtaposed in the close quarters of a rugby pitch as one team dances and the other cries.

Each player’s mind was filled with questions of what ifs and what abouts. The match had been lost in one single moment that would define so much that followed. With the clock ticking close to full-time and the Red Roses behind 34–31, hope ignited in the eyes of the England players as they were given the penalty that could save them. The decision was made to kick the ball straight out, from the five-metre line, and aim for a last-gasp try, a kick to the corner, a lineout and a driving maul; the cornerstone of England’s game. The tension reached its climax as the ball sailed towards the corner, and as the Red Roses rushed into their positions, they knew that everything was riding on this one act. Years of practice, hours upon hours of perfecting this move – which even had its own name, the ‘Tank’ – came down to one final moment. The steadfast dedication and unspoken sacrifices hung above each player’s head as they arrived to their position.

The ball was thrown and destiny hung on a precipice, suspended between triumph and heartbreak. If the ball lands in England’s hands, they can win the World Cup. If it falls to New Zealand, England lose the World Cup. Amidst the chaos of bodies grappling in the air, fate wrote its next chapter. With a ruthless display of skill and timing, New Zealand seized the opportunity that presented itself. In a fleeting moment of anguish, the ball slipped from the grasp of Abbie Ward, the England forward, into the clutches of the Black Ferns.

England were on a 30-match winning streak before this game. ‘Sport is cruel,’ uttered Sarah Hunter, the England captain in the final, moments after the final whistle had blown. She had been here before. New Zealand are England’s closest rivals and had beaten them in four World Cup finals before this one. Sarah had played in two of them, now three.

As the team moved slowly together and ambled into the changing rooms, words were quietly spoken and friends were embraced, in shock at what had just unfolded. For many of the players, this was the first time they had lost in an England shirt.

The journey from crestfallen warriors to resilient champions begins anew, immediately. It is in these moments of profound disappointment that the true character of a team emerges. In the days, weeks and months that followed, the team gathered their shattered dreams and channelled their resilience into determination. Never would they feel that way again. The pain of loss cuts deep. Never again.

And so, with a heavy heart but a strong resolve, they gather the fragments of their hopes and set their sights on the future, knowing that defeat today may well fuel the fire of triumph tomorrow.

Their challenge now is working out how to turn winners into champions. The team know how to win, but why couldn’t they win on the biggest stage? And what, if anything, can be gleaned from a match where victory hinged on the slightest of margins? It was in that very pursuit that the team turned to the percentages. As they regather and rebuild, they look at the 1 per cent improvements they could each make to take them that one, crucial, step further.

As a rugby journalist with a front-row seat to the captivating story of the Red Roses, I have witnessed first-hand the dedication, passion and resilience that define this remarkable team. I’ve followed their highs and reported on their lows, always inspired by their spirit. This is a special team full of exceptional women: they were the girls who insisted on playing with the boys, the teenagers who defied negative comments about women’s rugby, and are now the women who put their bodies on the line for the game they love.

I felt compelled to share their tale, offering you an intimate glimpse into the inner workings of one of the most revered rugby teams in the world. From the warmth of their homes to the hallowed grounds of training camps, players, coaches and staff (former and present) have graciously welcomed me into their fold. The team’s management have allowed me into the training camps and in meetings that are usually closed to the outside world, and the Red Roses have shared previously untold stories about life as elite women rugby players.

But why now, you might ask? In recent years, as interest in women’s rugby has developed, a growing fan base has emerged, hungry for a deeper understanding of the players they adore. An ITV documentary called Wear the Rose – which aired in November 2022 to preview the 2021 Rugby World Cup, ultimately played in 2022 due to the unforeseen circumstances of the coronavirus pandemic – showcased the players and staff who help the team go to new levels. As a rugby consultant on that project, I had the privilege of working closely with the production team, providing insights into the squad’s characters and illuminating the key storylines to follow in the lead-up to the tournament. This book, in many ways, serves as an extended cut of that documentary, presenting you, the reader, with an exclusive invitation to venture behind the scenes, to unravel the intricacies of the squad like never before. Together, we will unveil the untold tales, the hidden struggles and the indomitable spirit that define this powerful collective.

‘A book about the Red Roses?’ Marlie Packer, the England captain, asked, on a phone call just a couple of months after those World Cup exertions. ‘Will I be in it?’

‘Yes, you’ll be in it,’ I replied. ‘That’s why I’m calling you.’

‘I guess I’ll have to read it then,’ she said. ‘What are you going to say about me?’

The narrative begins by delving into the very origins of the Red Roses, tracing the humble beginnings of women’s rugby in England. It pays homage to the pioneers and trailblazers who have laid the foundation for the team’s ascent. To truly grasp the awe-inspiring nature of the current squad, we must take a moment to reflect on their historical context and remember the genesis of the game. From grassroots movements to the advent of professional contracts, and from horrified men stopping matches to world-record crowds, we’ll explore the pivotal moments that have moulded this team into the powerhouse they are today.

At the heart of this tale is the current squad, a remarkable group of athletes who have captivated the rugby world’s attention with their phenomenal skill and character. A modern history of the team shines new light on the rocky road from the amateur era to professionalism. The traits needed to become a Red Rose are also explored as four players from different backgrounds are followed on their quest to play for England. We’ll delve into their stories, the personal moments of triumph and their setbacks, to better understand the pressure on the shoulders of the England team.

The search by players and staff for the 1 per cent advantage they hope will win them the World Cup in 2025 is also examined and the background work that makes the Red Roses so successful is revealed, considering all elements of the high-performance environment that have propelled them to the pinnacle of sport. Conversations with unsung heroes, from the team’s nutritionist to the analyst, and every backroom staff member in between, offer insight into the hard-working men and women whose work often goes without mention. Crucially the culture in the squad, including where it has gone wrong in the past, and what needs to change in the future, is also put into sharp focus.

A deep dive into the on-pitch rugby, not only unravelling the tactical revolution that spurred England to a 30-match winning streak, but also considering (with help from a number of coaches and coach educators) how coaching women’s rugby is so different to the men’s game, concludes with a thought to how England’s tactics on the pitch have changed the game forever. But is that enough when they don’t win the World Cup?

Every aspect of the team’s World Cup journey in the 2021 tournament is also scrutinised. From the heartbreaking tales of non-selection to the previously untold stories of camaraderie behind the scenes, this book is there for every moment of an unforgettable competition.

The path ahead for the Red Roses is, naturally, the most pressing topic. In the aftermath of the 2021 World Cup the team went through a period of mass change, on and off the pitch, as coaches and captains left and attendance records were broken. The team is now on its way to greater heights but the road ahead has the potential to deliver more dramatic chapters in a captivating story.

Importantly, the off-pitch issues that lie in England’s path to success are also studied. From rugby’s battle with concussion, maternity right negotiations and social media abuse, the obstacles England – and women’s rugby in general – face are significant.

Beyond the glittering accolades and devastating losses, our exploration will extend to the broader impact of the success of the Red Roses. Their rise to prominence has not only enthralled audiences but has also ignited a fervour for women’s rugby, inspiring a new generation of players and fans alike. We’ll examine how their performances have led to increased participation figures and heightened recognition for women’s rugby in England and beyond, forever shaping the landscape of the sport.

The 2025 Rugby World Cup is on England’s home turf. It is important to look ahead to that tournament, contemplating its significance and its potential to elevate women’s rugby in England to new heights. We’ll consider the impact of England’s women’s football team winning the women’s European Championships, and if the Red Roses could grip the nation like the Lionesses did in 2022.

In writing this book, my sense of the team has been transformed, my respect deepened and my interest piqued. The Red Roses are a resolute group of remarkable women whose collective spirit radiates a brilliance that transcends sport. They are not just rugby players; they are role models, inspirations, feminist icons. But they won’t tell you that, so I will. These extraordinary and powerful women, driven by a hunger for success, exemplify courage and bravery not only in sport but in their entire lives. They have a rare calibre that would guarantee success in whatever field they turned their hands to and yet they chose rugby union, and for that, we are eternally grateful.

Chapter 1

THE PIONEERS

Women’s rugby is a feminist issue. It always has been. Rugby is traditionally a male sport, and for many years it was seen as too violent for women. Being a rugby player goes against the gender stereotype of womanhood; it’s messy, brutal, loud, confrontational and dirty. And it’s wonderful. The appeal of the sport goes beyond a means of protest, of course, but its heart is in challenging the standards set by men and its history is in pioneers who have never taken a step back on their fight for the sport.

To play rugby as a woman has often been considered in history as a political statement; a chance to visibly show what women’s bodies were capable of. And for over a century, women’s rugby was vastly unpopular. So unpopular, in fact, that during the first women’s rugby match on record in England, spectators ran on to the field to stop play. A newspaper report from the time read: ‘The lady footballers played on the old Southcoates ground opposite the Elephant and Castle, Holderness Road, on Good Friday, April 8th, 1887. The spectators broke into the playing area and stopped the match.’

It is within the context of such adversity that the spirit of women’s rugby was born. The significance of the sport reaches far beyond the touchlines of the playing field; it embodies a fight for recognition, a quest for equality, and a belief in the power of women’s resilience.

Dr Victoria Dawson, a historian exploring female involvement in rugby league, discovered evidence of this first women’s rugby match on English soil while trying to work out who the first woman or girl documented as playing rugby in the world is. Also in 1887, a ten-year-old girl called Emily Valentine joined in with her brothers when their school team, in Ireland, was a player short. Emily is often credited with being the first girl to play rugby, thanks to John Birch from Scrum Queens who discovered her diary, but of course it’s likely there were other girls who played the sport with brothers in gardens or behind closed doors. But it was never documented, because such an act would be seen as inappropriate and unwomanly.

In sharp contrast to the disdain of early women’s rugby reports in the British media, New Zealand seemed to be far more supportive of their women’s rugby players. In 1891, a newspaper report spoke positively about the sport and detailed the support around the players. The ‘enterprising young damsels’, as the newspaper article uncovered by Professor Jennifer Curtin reads, had their hair cut short to ‘prevent accidents’ and would be ‘provided with costumes designed so as to give the freest use of their limbs, consistent with their ideas of propriety’. The text reads as far more supportive of the women, suggesting they have ‘a fair degree of proficiency in manipulating the leather’.

Across the world in the late 19th century, women were beginning to challenge their gender roles and campaigns for the right to vote gathered steam. In New Zealand, women’s rights movements had comparatively good support and it was the first country to grant women the right to vote in 1893.

In Britain, the Victorian era held strong beliefs about ideals of femininity and masculinity. Women were expected to limit their ambitions to marriage, motherhood and having a clean house. Those beliefs were ingrained in the fibres of society and generally followed, despite Queen Victoria being a powerful monarch. ‘The woman’s power is for rule, not for battle,’ wrote imminent social thinker John Ruskin in 1865. ‘And her intellect is not for invention or creation, but for sweet ordering, arrangement, and decision . . . she must be enduringly, incorruptibly good; instinctively, infallibly wise, wise not for self-development, but for self-renunciation: wise, not that she may set herself above her husband, but that she may never fail from his side.’ So not much time for rugby training, then.

It would take the First World War to shift attitudes towards women. With men away at the front, many women took up jobs that had previously been seen as too dangerous for women. They operated dangerous machinery, sometimes were exposed to harsh chemicals, and often had to transport heavy goods like coal. The idea of women’s work completely changed during this time.

One role that a lot of women turned to was keeping the munitions supply chain roaring along during the war. The women who worked in those factories became known as ‘munitionettes’ and factory owners often allowed their workers to form sports teams in a bid to boost morale and keep the workforce fit. In a time when attitudes were shifting and women were finding their power, some munitionettes chose to play rugby.

By 1918, the year the First World War ended, there was a well-received and popular women’s rugby set-up in Wales, particularly on the industrial south coast, as Dr Lydia Furse, a women’s rugby researcher, found. On 29 September 1917, there was a women’s rugby match at the Cardiff Arms Park between two teams from the Newport munitions factory, which was described by the Western Mail at the time as ‘a wonderful display of scrimmaging, running, passing, and kicking’ and said the players ‘pleased the spectators immensely by their vimful and earnest methods.’

The movement peaked when 10,000 people were reported to have attended a match between Cardiff and Newport on 15 December 1917 at the Cardiff Arms Park. Maria Eley, the full back for Cardiff, remembered the match 83 years later, the year before she died: ‘It was such fun with all of us together on the pitch, but we had to stop when the men came back from the war, which was a shame. Such great fun we had.’

At the same time as rugby’s much smaller revolution, England’s flourishing women’s football scene was gaining international acclaim. Its roots were also in the munitions factories that women had kept going while the men were away with the war. Many war factories across the UK had a women’s football team. In Preston, women at the Dick, Kerr & Co factory formed a football team and trained around their shifts. As their skills developed, they challenged a neighbouring factory, the Arundel Coulthard Foundry, to a competitive game to raise money for charity. They drew in a crowd of 10,000 people who watched the Dick, Kerr Ladies win 4–0. ‘Dick, Kerr’s were not long in showing that they suffered less than their opponents from stage fright, and they had a better all-round understanding of the game,’ read a report in the Daily Post at the time. ‘Their forward work, indeed, was often surprisingly good, one or two of the ladies showing quite admirable ball control.’

Across the country, women’s football was soaring in popularity. The matches were known to attract 50,000 spectators and the proceeds were often donated to support injured servicemen. Alas, men returned from war and for most women, life soon reverted back to how it had been before. Some, not all, women were granted the vote in 1918, but the efforts of women to emancipate themselves in other areas of life had largely fallen flat.

Women’s football gathered steam for another few years, and in 1921 the Dick, Kerr Ladies reached a new height. They played over 60 games of football that year, on top of full-time jobs, in front of an estimated total of 900,000 fans. The roaring success of the sport faced an abrupt end on 5 December 1921, when the Football Association (FA) issued a ban which did not allow any member club to let women’s teams play on their grounds. The FA were worried that the popularity of the women’s game would take money away from the men’s game after the war, and also suggested the money raised from women’s football was being spent ‘frivolously’ when they believed more of the money should have gone to charity. No such rule existed in men’s football.

Women’s football was sidelined. Minutes from the meeting called football ‘quite unsuitable for females’ and decided it ‘ought not to be encouraged’. Leading doctors began to agree that football was unsuitable for women. They said the physical nature of the sport was too much for women to handle and could prevent women becoming pregnant. Women had proved their physical abilities in the war but had been once again been tied down to the roles society at the time handed to them: stay home, have children and be a good wife.

Women’s rugby in the United Kingdom did not recover after the war and the efforts of those early pioneers were largely forgotten in history. It wasn’t until the 1970s, amid the second wave of feminism, that women’s rugby took off once again. This time it was universities who introduced women to the sport; firstly in the USA, Canada and France. Interestingly, there is evidence in France of a version of rugby deemed more suitable for women, called barette, being developed in the 1920s. In the USA, women’s rugby proved vastly popular, which some believe is because rugby union was not a popular sport for men, and therefore women received less opposition to playing it. Kevin O’Brien, the head coach of the USA team who won the inaugural Women’s Rugby World Cup in 1991, says rugby had become a political statement for American women. ‘A lot of the women involved weren’t supposed to be doing this, but basically they said, “Screw you, you can’t stop us; we’re going to play,” because there was a lot of resentment and a lot of putting down of women in sport,’ he told me in 2022. ‘It was on the forefront, the cutting edge of women in sport. Well, there were no other contact sports. The rules in this country [the USA] for all sports are different for women. So for a lot of women, to get out there and play in a contact sport was a political statement.’

It is no coincidence that rugby attracts women during the waves of feminism. It is one of the most physically challenging sports for women. People of all shapes and sizes can thrive in rugby – no longer constricted to being small – and the sport teaches assertiveness and aggression in a way that society for so long deemed inappropriate for women. Across the world, playing rugby was a way of repealing the constructs of society and physically asserting their abilities.

In England, women’s rugby hubs began to appear around the country with students and graduates, with many teams who would gather at an annual tournament in Loughborough. In February 1982, University College London (UCL) travelled to France to play teams including Pontoise, and found a well-organised domestic competition there that ignited a desire to lift the game in Great Britain. As such, the idea of the Women’s Rugby Football Union (WRFU) was founded.

The union represented players from England, Wales and Scotland with 12 founding teams, all from universities in England, except the Magor Maidens, a rugby club in South Wales. The organising committee planned a meeting at the Bloomsbury Theatre in Euston in 1983 to discuss their objectives, and at first decided to focus on growing the participation of women’s rugby and establishing teams outside of universities. But when a touring team from America, known as the Wiverns, came to visit and won 44–0 on two separate occasions, it prompted the realisation from the WRFU that the creation of a Test side was a crucial next step for the union, to limit the risk of Great Britain being left behind as countries such as the US, France and the Netherlands led the way with strong women’s rugby teams. Great Britain played a total of eight matches in the following years, but by the mid-eighties each respective country felt strong enough to begin to establish their own national teams. In 1987 England played Wales, winning 22–4 at Pontypool Park.

The next four years were monumental for the development of women’s rugby globally. National teams were forming and competing, leading to the idea that there really should be a World Cup for the women. But the International Rugby Board (IRB), which is now World Rugby, had little interest in supporting such an idea, and the women’s game in England was still operated solely by volunteer administrators and, frankly, hard-working women who refused to take no for an answer.

When Richmond, a hub of women’s rugby in south London, toured New Zealand in 1989, they shared contact details with the teams in Canterbury and Christchurch with the idea of playing more regular competitive fixtures with teams abroad. The men had their first World Cup in 1987, which cemented the idea in the heads of four women – Deborah Griffin, Sue Dorrington, Alice Cooper and Mary Forsyth – that a women’s World Cup would be a truly excellent showcase of what the sport had achieved in recent years.

The four women gathered in the early mornings before work, at lunchtimes and after work to hatch a plan. They had little money or support, but they had an overwhelming desire to turn a brilliant idea into reality.

There were many logistical challenges in the beginning. The first being that before the age of social media or emails, it was hard to work out which unions had women’s teams. The organising committee knew that the USA, Canada, France, Netherlands, Spain and Sweden had teams, but were unsure of other countries. They wrote to them to ask if they had a women’s team, and if that team would fancy playing at a World Cup. All correspondence was done via fax, Deborah recalls. She still has a file full of those messages. Even though the ink has long faded, Deborah wouldn’t dare part with her folder of blank white pages that symbolise so much.

The committee used a sponsorship agency to help fulfil their promise to the visiting nations that they would cover all accommodation fees. Two months from the start date, the money had not been raised. Griffin and her coorganisers were left with no option but to sheepishly write to the unions to tell them that the inaugural Women’s Rugby World Cup would have to be cancelled.

To their shock, each union wrote back to say they would still be coming. The four women realised that their mission to host the first Rugby World Cup had transformed into a mission held by players across the globe, all happy to dig into their own pockets to see the vision become a reality.

Cardiff was chosen to be the host city, due to its abundance of university accommodation, links to rugby and genuine desire to host the tournament. There was local support for the competition, as clubs across South Wales opened their doors to host matches and club members cheered along the touchline, but there wasn’t any live broadcast interest, and only a little pick-up from national media. The Welsh Rugby Union provided referees for the tournament, clubs offered what they could, and players from different nations pulled together to make ends meet.

All that was left was to welcome the players and get the tournament started. The nine-day competition commenced with the opening ceremony. It was the first time that some of these international teams had met. The hard work was just about to begin, but for that night, there was celebration for the game and the shared passion that had brought them all together. A band played as teams marched in, some dressed smartly and some in tracksuits. People gave speeches and the event felt like a milestone in rugby union history.

The competition ran smoothly, despite atrocious weather at times and the most peculiar run-in with HMRC. The Soviet Union team arrived with no money or equipment to play rugby with. Unable to take money out of their country, the team arrived with arms full of vodka, dolls, caviar and cucumbers to haggle their way through the tournament. Their plan was to sell the goods on the streets of Cardiff, only for HMRC to knock on their door at the Cardiff Institute of Higher Education to tell them they could not do such a thing.

‘The women were said to have travelled through Heathrow Airport’s green channel with five 5ft cases of liquor, but at South Glamorgan Institute yesterday customs investigators found it almost impossible to break the language barrier and eventually left,’ a Guardian report from 1991 reads. ‘It is understood that no charges will be brought against the team, who had only enough money for their air fares and hoped to barter their goods for food during the week-long tournament in South Wales.’

The team managed to get by thanks to donations from the local community. A local store donated jerseys, another donated clothes and companies gave them money to help pay for their accommodation. Among other donations, a pie factory delivered produce to the players’ accommodation to fuel them for the World Cup.

The team eventually finished the tournament with zero points to their name and left some debts for the hosts too. Even now, 30 years later, there is a raised eyebrow and pursed lips on the faces of the organisers when the Soviet team are mentioned. The story demonstrates just how hand to mouth the event was and how challenging it was for the organisers.

The tournament is best summarised by David Hands, rugby correspondent for The Times in 1991: ‘The event, which reached its climax on Sunday in Cardiff when the United States beat England 19–6 in the final, has been run on a shoestring, with none of the trappings of the modern men’s game – no big sponsors, no back-up, limited accommodation, but huge reserves of enthusiasm and considerable organisational skill.

‘It was a tournament run for players by players who were prepared to risk their own money to bring their particular dream to fruition, and in that sense has taken rugby back to its original and purest roots.’

In fact 1991 is seen by many as the starting point for women’s rugby history. Of course it was not, as this chapter has gone some way to describe and as previous written accounts have demonstrated. Scrum Queens by Ali Donnelly is the greatest source for a detailed delve into the history of the sport globally, and World in Their Hands by Martyn Thomas is a fantastic book about the 1991 World Cup.

This whistle-stop tour of women’s rugby history in England does little justice to the rich stories of the most terrific women who made it their mission to shine a spotlight on the game, but should help acquaint readers with the women who fought tirelessly to get the game off the ground.