Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

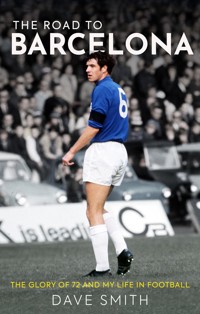

'EIGHT YEARS WITH RANGERS, MORE THAN 300 GAMES, INCREDIBLE HIGHS, PAINFUL LOWS – AND IT ALL CAME DOWN TO ONE NIGHT IN THE NOU CAMP' 24 May 1972. The biggest night in the history of Rangers. Having overcome the might of Italian giants Torino and Beckenbauer's Bayern Munich en route to the final of the European Cup Winners' Cup, Dynamo Moscow stood between the Light Blues and the trophy. The stage was set in Barcelona for an unsung hero: Dave Smith. Creator of two of the goals on the night and arguably man of the match. In a rollercoaster career, Smith joined the Ibrox club from Aberdeen in 1966 for a record fee. He tasted defeat in the 1967 European Cup Winners' Cup final and had his career blighted by two horrific leg breaks during a period in which he also experienced the tragedy of the Ibrox disaster. But by 1972 Smith was a lynchpin of Willie Waddell's team. Playing as sweeper, he dicated the tempo of games with his vision and pinpoint passing. The star of the Nou Camp victory was voted Player of the Year in Scotland to cap the most memorable of seasons. He departed Rangers in 1974, making a shock switch to Arbroath after a fallout with new Ibrox manager Jock Wallace, before going on to star overseas in South Africa and then alongside George Best for the LA Aztecs in America. Rejecting the chance to join Paris Saint-Germain, Smith chose to end his career in Scotland's lower leagues as player-manager at Berwick Rangers where he would find success and happiness playing the game the way it was meant to be played.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 405

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ROAD TOBARCELONA

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2022 by

ARENA SPORT

An imprint of Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Dave Smith and Paul Smith, 2022

ISBN: 9781913759032

eBook ISBN: 9781788853279

The rights of Dave Smith and Paul Smith to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburgh

www.polarispublishing.com

Printed in Great Britain by Clays, St Ives

To Sheila – the light in my life then, now and always.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FOREWORD: Colin Stein

INTRODUCTION: ‘Just another game’

1: ‘Barcelona belonged to Rangers’

2: ‘You could dare to dream’

3: ‘Nothing worth having comes easily’

4: ‘The foundations were laid in Nuremberg’

5: ‘The story that we all wish did not have to be told’

6: ‘The battle to get back on the pitch’

7: ‘From the gloom came some light’

8: ‘We didn’t just beat Bayern, we pulled them apart’

9: ‘If you can survive Gullane, there’s nothing in football to fear’

10: ‘This was our time and our chance to be heroes’

11: ‘The calm after the storm’

12: ‘The big occasions were the motivation for me’

13: ‘Rather than soaking in the success, what followed was uncertainty’

14: ‘One of the few major regrets I have in football’

15: ‘There was no shortage of stardust around the LA Aztecs’

16: ‘I realised as manager I was free to play the way I liked’

17: ‘Not the ideal place for an unashamed football idealist’

18: ‘As the years pass the reunions become smaller’

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THE ANNIVERSARY OF the triumph in Barcelona is a time for celebration and for reflection. Above all else, my eternal thanks and love go to Sheila for being by my side through the highs and the lows, for better and for worse. I’ve had good luck and bad, I’ve made good choices and I’ve made mistakes – the best fortune is nothing to do with football and everything to do with family and the love and support I have had. I am so incredibly proud of Sheila and our children Amanda, Melanie and Paul, as well as of Pascal, Zak and Tom (Melanie’s family) and Coral, Finlay, Mia and Zara (Paul’s family). To work with Paul so closely on The Road to Barcelona has been a privilege that few father and son partnerships get to share and I’m grateful to all who have been part of bringing this story to life, not least the team at Arena Sports for their faith in the project, and also Dave Hamilton and Ian McLean for their meticulous work in the background, as well as Colin Stein for his kind words of introduction. My thanks too go to the many who were there with me through my time in football and beyond, the men I was proud to call my team-mates. Finally, my appreciation to all in the Rangers family, including all of my good friends in the Dave Smith Loyal Fraserburgh RSC, whose warmth and affection has never wavered in the 55 years since I first pulled on the famous blue shirt.

Dave Smith

OVER 15 YEARS as an author and across 18 books I have had the pleasure of telling some wonderful stories. In all that time, The Road to Barcelona remained an idea in the background, one to save for another day. Now is the right time and I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to have worked with my dad to look back over an illustrious career in football that played out, in the main, before my time. For my sisters and I, dad has always been the football hero and mum the real-life hero – both deserve to take a moment to look back at all they have achieved together with huge pride. This book would not have been possible without a team in the background, led by Hugh Andrew and Neville Moir at Birlinn and Arena Sport, supported by Peter Burns, Alan McIntosh and the photographers and image archivists whose pictures feature in the pages that follow. Special mention to Colin Macleod, a source of constant encouragement and support over many years. My appreciation also goes to the journalists and writers who went before me, many long since departed, but whose work lives on, providing such rich context around which this story has been built. The last words are reserved for Coral, Finlay, Mia and Zara for the love and the laughter, the fun and the contentment that makes every day a joy – the real dream team.

Paul Smith

FOREWORD

BY COLIN STEIN

FOOTBALL HAS ALWAYS been a game of comparisons, players held up against those that went before them and whoever followed next.

Every now and again someone comes along who breaks the mould and does things differently. I had the joy of sharing a dressing room with one of the best examples of that: Dave Smith.

It’s a pleasure to introduce the story of a teammate who played such an important role in what has been such a big part of all our lives.

On the road to Barcelona in 1972, and in the European Cup Winners’ Cup final against Dynamo Moscow in particular, Dave was at his very best.

I can still replay the opening goal in my mind, his raking ball cutting open the Russian defence, my touch and then the shot nestling in the back of the net. Dave laid on another with the fantastic cross for Willie Johnston’s headed goal before Willie got his second to give us the cushion to see us through to that famous 3-2 win and bring a European trophy to Ibrox.

In defence and attack Dave was the conductor for us in the final, organising and cajoling everyone around him and then picking his moments to break forward and carve out opportunities when the time was right.

For anyone who saw him play regularly or lined up alongside him every week, it was no surprise that he stepped up when it mattered most. Pressure didn’t seem to register with our No. 6.

He had that ability to see things that others didn’t and pick opponents apart with a left foot which was as sweet as could be. I’ve seen him described as a Rolls Royce of a football player, and that’s very fitting for a player who played the game with such elegance.

He was, in my view, a unique player.

Mind you, that didn’t stop those comparisons I mentioned. From Jim Baxter to Bobby Moore, Franz Beckenbauer and many more in-between, Dave was held up in that type of company. That says a lot about what the supporters and football writers thought of him when he was in his prime – but, as you’ll read in the pages which follow, he didn’t want to be compared to anyone.

He thrived on doing what others wouldn’t dream of – whether it was nutmegging opponents in his own box, mazy dribbles through swarms of players or arrowing balls from one corner of the pitch to the other. I can’t think of anyone who did it quite the way he did.

As a forward, Dave was a dream. If you made the run, you knew that 99 times out of 100 the ball would hit you.

In other ways, a total nightmare! There’s nothing that gets the heart racing faster than looking back and seeing one of your defenders weaving out of the 18-yard box as if he were playing a kick-about with his pals in the school playground. It was never any different – Old Firm fixtures and cup finals were played the same way as any other game. Underneath it all, there was a burning desire to win.

In fairness, he had the ability (and the self-belief) to play the game his way. He’d be the first to tell you we had nothing to worry about!

That confidence on the pitch was a hallmark of a player who is a true Rangers great, immaculate in everything he did.

That swagger was left at the tunnel entrance, though. Off the pitch he’s a down-to-earth character. Those who don’t know Dave might say he’s shy – those of us who do would tell a different story. Once he’s comfortable in your company that’s when you really get to know him.

Dave was a big character in our squad, one of the leaders in the group on and off the park. That came to the fore in ’72 in some style.

I hope you enjoy reading about his life in football as much as I did being part of it.

INTRODUCTION

‘JUST ANOTHER GAME’

JUST ANOTHER GAME. It’s a phrase I’ve used so many times to describe those 90 minutes in the Nou Camp and the big matches on the road to Barcelona.

For me, no match was any different. Right back to my first steps in the game through to European finals in my prime and then the final throes of a long career, the only pressure I felt was from within.

To be the best, to take a chance, to be different, to do the unexpected, to entertain.

Everything on the outside – managers on the sidelines, the opposition, the expectation of supporters, media interest – didn’t really matter. To talk about pressure and football in the same breath just doesn’t make sense. It was a pleasure. If I could go back in time and do it all over again I would in a heartbeat.

In that sense, when we crossed the white line to face Dynamo Moscow at the Nou Camp on 24 May 1972, it was just another game.

The truth for all of us who came back into the dressing room as European Cup Winners’ Cup winners that night is that it wasn’t just another game. It changed our lives forever.

Ninety minutes that have touched everything that has followed. We know now that it was a huge moment in time. We didn’t know it then, and I haven’t ever really acknowledged it since.

Fifty years on, it feels like the right time to reflect properly and to replay that period while it’s still vivid in the mind.

What follows isn’t a football autobiography in the traditional sense. For one, I don’t think you want to know the ins and outs of my table tennis triumphs as a young boy or about my retirement in the glens. More importantly, there are parts of my life that I will forever keep private. For that I make no apologies.

The Road to Barcelona brings together my recollections around the glory of ’72, the foundations it was built on and the experiences in the aftermath.

For those who were there or who joined the party when we arrived back in Glasgow, I hope I can do justice to the memories we share.

For those too young to have experienced it first hand, you’ll have to trust that we really did have the privilege of living through the best of times.

The fact that half a century on we hold the honour of being the only Rangers team to have brought continental silverware back to Ibrox is something that not one of us would have predicted.

I was one of those who had suffered the pain of defeat against Bayern Munich in the final of the same competition five years earlier, and to lay that to rest in Barcelona was an incredible feeling.

When we stepped off the plane on home soil with the trophy in hand, we felt ready to take on the world. Never mind waiting decades, we believed we could and would go on to win on that big stage again the next year and for years after that. You feel invincible.

The history books tell a different tale, and who knows when that time will come again. I’ve seen a lot over the years, the domestic dominance and glimmers of hope in Europe. I’ve sat in the stands during the darkest of days and been there for the revival, at home and abroad. I’ve felt the pain and shared the hope. Like everyone with Rangers in their heart, I’ll never say never.

Until then, the memories of ’72 carry through the generations. It’s a story worth telling.

ONE

‘BARCELONA BELONGED TO RANGERS’

EIGHT YEARS ON the Rangers playing staff, more than 300 competitive games, incredible highs, painful lows – and it all came down to one night in Barcelona.

When we boarded the plane to set off for Spain, it was a huge relief. All the waiting and all the hype were left behind at the departure gate. It was our time.

And what a time it was!

T-Rex, Elton John, The Drifters and the Rolling Stones were in the top 10, and Led Zeppelin were heading for Green’s Playhouse to entertain an appreciative Glasgow crowd.

Diamonds are Forever and The Godfather were breaking all sorts of box-office records at the cinema, and Emmerdale Farm and Are You Being Served? made their TV debuts. French Connection was making waves as the new brand on the fashion scene, and the Ford Cortina was flying off the forecourt as the UK’s bestseller.

In sport, the Olympic torch was wending its way to Munich for the summer games, and Lee Trevino was heading for Muirfield to defend his Open title. Brian Clough led Derby County to the English championship, collecting his first trophy as a manager. What would become of him?

The average house price in Scotland was £7,000, and the suburbs were beginning to sprawl as the likes of John Lawrence and Wimpey continued to cater for the masses. In the city, the skyline was changing as the tower blocks continued to rise from the ground.

It wasn’t all good times, far from it. The Upper Clyde Shipbuilders protests were in full swing as the spectre of yard closures and thousands of redundancies loomed amid massive political unrest. The year had started with the miners’ strike – and by February power shortages were leading to restrictions and managed power cuts as the authorities tried to keep the lights on across the UK.

I would love to say I remember all of that and it’s ingrained in my memory in glorious technicolour.

The truth? As a player, you’re so wrapped up in your own wonderful little bubble that very little on the outside gets through.

Music, films, TV, cars – that wasn’t me. Football was what my life revolved around, and the week that lay ahead was huge. It would end either with a winner’s medal to mark my Ibrox career or leave me still searching for silverware.

From a personal perspective, the clock was ticking, and I knew that. I was six months away from my 29th birthday and it was an era in which 30 was considered an old man in football terms. I’d been at the club for six years and had nothing to show for it through a combination of bad luck and more bad luck. This was the chance to put all that right in one game.

All things considered, you’d think tensions would be running high – but nothing could have been further from the truth. As a group we were in great spirits. I don’t think there was a single player who climbed the stairs to that plane who had any doubt that we were bringing home the cup. The doubt maybe crept in 80 minutes into the match for some ... but that’s for another chapter.

That confidence came from the talent we had and the belief there was in what we had set out to achieve in Europe when the adventure had begun eight months earlier.

It’s fair to say it didn’t come from a sparkling season on Scottish soil, and that, if anything, makes the success of ’72 all the more remarkable.

In the league we had finished third, short of top spot by a long stretch and six points behind Aberdeen in second place after an indifferent end to the season. Once the championship had gone, results understandably tailed off – playing for a runners-up medal is never the biggest incentive. Of course, you want to win every game, but the edge is gone as soon as the big prize is out of reach.

I was once fined by the football authorities for declining the honour of picking up a Highland League Cup runners-up medal as player-manager at Peterhead in the early 1980s, on the back of a refereeing performance that left a lot to be desired. You might call it sour grapes, the association certainly saw it as disrespectful. You could argue both, but being a good loser isn’t a quality I’ve ever claimed to have.

The problem we had at Rangers at that time was we had been second too many times and we were desperate to put it right for the supporters as much as for ourselves. I can’t begin to explain how much it meant to do that in Europe.

I’d arrived from Aberdeen in 1966, and the aim was to wrest the league trophy back from the other side of the city. In that first season we were three points short after three draws in the last three games of the campaign. The next year we lost out by two points after a draw and a defeat in the final three games, our only loss in the league that term.

And so it went on. The league table might have told a different story at times, but we never felt there was a big gap. As a squad we didn’t feel inferior, but nobody remembers the team which comes second.

It was a difficult time to be connected with the club, and we needed to put smiles back on faces.

Derek Johnstone had done that 18 months earlier with his winner against Celtic in the 1970 League Cup final, something everyone hoped would be a springboard to better times and was probably the point the tide began to turn. I missed that final with one of two broken legs I suffered in that period (see my earlier note about bad luck).

That was Willie Waddell’s first trophy as Rangers manager and was a case of laying down a marker.

Waddell is a figure who features prominently in the pages which follow and a character so integral to Rangers as a player, manager and administrator. It feels wrong not to be calling him Mr Waddell, even now, but maybe it’s time to lay that deference to one side.

He was one of four managers I served under in a blue shirt, and all had their own attributes. In the case of Waddell, it was a knack for making the right calls at the right time.

He arrived late in 1969 when the only way was up, and he left the manager’s office on his own terms in the summer of ’72. His signings paid off, his team selections and tactical changes more often than not worked out. You could call it good fortune or managerial nous, but whatever it was it worked in our favour.

We had our moments – as you’ll begin to understand, I wasn’t the easiest to coach – but there was a mutual respect. He had a presence and the confidence you need to be a Rangers manager, built on his reputation as a player. Not that any of us were in awe of a legend returning, but we knew he was a man of substance.

Waddell had replaced Davie White. The circumstances are well told, but worth repeating. Having led Kilmarnock to the league title, Waddell had made the astute decision to step aside while the going was good and went from gamekeeper to poacher as a football writer. He was critical of White – the Boy David as he had called him in print – and eventually the pressure from all sides told. The decision was made, and it was out with the new, in the shape of White, and in with the old, in Waddell.

I’d watched him from the terraces as a boy and remembered him as a powerful winger, fast and direct. He’d lost none of that presence when he swapped playing kit for a suit, heavier than his playing weight and cutting an imposing figure.

In later years I watched from the outside as he made his mark as a manager at Kilmarnock. What he achieved at Rugby Park, winning the championship in 1965, was remarkable, and when we talk of the great Scottish managers I think he’s all too often overlooked. With Killie and then Rangers he did things which are unlikely ever to be repeated.

I also got to know Waddell as a football writer, one of the inner circle of Scottish pressmen. The relationships between that press corps and players were sacrosanct – we trusted them implicitly, knowing that anything we told them privately would stay that way. We regarded them as friends.

Waddell was one of the callers to the room John Greig and I shared in Poland, when we travelled out to play Gornik Zabrze in the European Cup Winners’ Cup in November 1969 and fell to a 3-1 defeat in the game that sounded the death knell for White’s time in charge. He came to pick the bones of that game and that result over a post-match drink. If he knew at that stage he would soon be swapping the press box for the dugout he never let on to us.

But that’s exactly what transpired. White was shown the door, and the red carpet was rolled out for Waddell. It was quite the comeback for a seemingly retired manager, although he was only 48 when he took on the job at Ibrox.

It was an interesting change of direction for the board, who had gone with White as a nod to the changing of the guard in Scottish football. Coaching was evolving, and the directors had been looking at what was happening elsewhere – Eddie Turnbull at Aberdeen, Jock Stein at Celtic – and wanted to make that transition. The age of the tracksuit manager was upon us.

White was in that image, a coach rather than a traditional manager.

That was night and day to Scot Symon, the man who had brought me to the club.

We didn’t see a lot of Symon day to day. He would appear occasionally, dapper in his suit and bowler hat, but his role was far less hands-on than those who followed him. He made the signings and picked the team – although the side practically picked itself. There was no rotation. It was the best 11 week to week, and I’m a great believer that’s the way every player would want it. That was the case in the 1960s just as it is in the 2020s. You don’t feel tired when you pull your boots on and run out of that tunnel.

Symon was a true gentleman and, quite rightly, a Rangers legend. He could have been treated better by the club, and it was painful to see it end the way it did for him when he was relieved of his duties in November 1967. We all liked and respected him, and as a player you always feel a responsibility when a manager loses their job, particularly one you admire and feel indebted to. He’d given me my dream opportunity, and I’ll forever owe him for that.

The sacking was as much of a surprise to the players as it was to the manager. John Greig and I were at the TV studios in Clydebank to record Quiz Ball (think University Challenge crossed with Question of Sport and you’ll not be far away), with the inimitable Rikki Fulton as our guest supporter. The manager, who was leading the quiz team, had run us there and back to Queen Street station at the end of the show. He was in good spirits, and there was no indication anything was afoot. The next morning, he was gone.

In case you’re wondering, we lost the quiz 3-1 to Tottenham Hotspur, and by the time it was broadcast they had the awkward situation of having the former Rangers manager as one of the team captains.

With White, we had more of an inkling that it was not going to end well. The mood music wasn’t good, and the negativity was growing.

White didn’t have the authority or the aura of the Rangers managers who went before him or who followed after. He didn’t have the media presence or the stature. That wasn’t something he could change – he had the football brain, there’s no doubt about it, and I genuinely believe he could have gone on to have success at Ibrox. It was a brave appointment – but the board didn’t have the confidence to see through the project, understandably spooked by results and the signs they were seeing.

If there was a criticism of White I would say it was that he perhaps didn’t understand the enormity of the job he had or the responsibility that went with it. I’ve no doubt that dawned on him further down the line. We would all love the benefit of hindsight after all.

He allowed himself to get too close to the players. He wanted to be one of the boys. I’ll always remember one trip overseas, watching him finishing his meal on the table with the directors and being first on the dance floor. No big deal, but not what you traditionally see from a Rangers manager!

Safe to say, he wasn’t a disciplinarian like those before and after him.

We were used to having to creep back to our rooms if we’d stayed out for a nightcap later than we should have done when we were on tour. With White, we got an invitation to carry on through the night and go straight to training rather than being packed off to bed. I can remember the directors watching one of those drills, not knowing we were more than a little the worse for wear and no doubt wondering why on earth we weren’t exactly setting the heather alight as we fired crosses at Alex Ferguson, standing forlorn in the penalty box, and not a single one landed.

If White seemed to be a fish out of water, Waddell was made for the job. He looked the part and spoke a good game. The directors had turned to the Ibrox establishment, and it paid off in great style, not just with the cups he won but with the foundations he laid and the team he assembled on and off the park.

Waddell had the stubborn streak that you need as a Rangers manager, knowing that he could afford to be so because of the power that goes with having your name over the door.

When you ventured up the marble staircase at Ibrox to the manager’s office, with him sitting behind the big old wooden desk with his glasses propped on the end of his nose, you invariably knew the answer to whatever question you were about to ask. Usually, it was an emphatic no.

Not long after he arrived as manager, the players held a meeting downstairs to discuss joining the players’ union. It was a movement which was just starting out, the infancy of PFA Scotland as it is now, and it made perfect sense for players to try and establish that collective voice. The decision was made – the Ibrox squad wanted in, the players had spoken.

John and I bounded up the stairs to pass on the good news to the manager, pressed the buzzer outside and waited for the light to glow to allow us in. You never entered when the red light was showing, you always had to get permission.

In we went and told him the decision the players had made. He peered over his glasses and quite calmly said: ‘You’ll no be joining any union.’ Matter closed, end of story. So much for player power.

After I broke my leg for the second time I made another trip up the stairs, pressed the buzzer and waited to be summoned in. Up to my knee in plaster and on crutches, I was there to ask for a couple of complimentary tickets for the next game. He looked me up and down and asked, ‘Are you playing at the weekend?’

‘Do I look like I’m playing?’

‘Well, you know the rules – there are only tickets if you’re in the squad.’

And off I hobbled.

Ten minutes later the doorman, Bobby Moffat, came and found me. He went to hand me two tickets courtesy of ‘the Boss’ as Bobby called him. I told him to go and tell ‘the Boss’ to stick the tickets wherever he liked. I don’t think that message got passed on – Bobby was a bit more diplomatic than I ever was!

That was the way Waddell was. He liked everyone to know who was in charge, and I respected that. It helped that he liked me as a player too. He had always given me good reviews in the papers and one of the first things he did was put me back in the team after the failed experiment bringing Jim Baxter back under White.

He was ruthless in that sense. It didn’t matter if you were idolised on the terraces. Baxter went out the door, Willie Henderson was allowed to move on before the European final, and Willie Johnston and Colin Stein likewise after Barcelona. Brave decisions, although not the right one in the case of Bud and Steiny who in time were brought back.

In his first full season, Waddell took the League Cup back to Ibrox, and in his second it was the European Cup Winners’ Cup that was within reach as the summer of ’72 loomed – even if circumstances conspired to make it not the smoothest build-up to the final.

From playing our last league match, a 4-2 win at home to Ayr United on 1 May, to lining up against Dynamo Moscow, we had a three-week lull. As preparation for the biggest game of our lives, it was far from ideal.

Bizarrely, there was talk of us flying out to Indonesia to play an exhibition match against their national side. It would have been an odd time to be trekking across the world to play in tropical conditions, but you learnt to expect the unexpected. That one never did come to fruition, and I don’t think our preparation for the cup final suffered for not taking on that particular challenge.

The solution was to slot in a couple of bounce games, although the choice of opponents raised a few eyebrows in our own camp and I’m sure it did on the outside too.

The might of an Inverness Select, drawn from the Highland League, were our first opponents. A Wednesday night encounter at Grant Street Park, home of Clachnacuddin – just the thing to get the pulse racing! It wasn’t quite the Nou Camp in terms of scale or climate.

It was a testimonial match for Ally Chisholm, Ernie Latham and Chic Allan. It was the first time a Rangers side had been in Inverness for 20 years, and the hope was that it would draw a big crowd to keep us on our toes. In the end it pulled in more than 7,000 supporters, so it served its purpose.

Andy Penman, more naturally considered a winger, was played in the middle of the park that night as the manager tinkered a little with the approach and looked at his options for our trip to Barcelona.

My hunch would be that he wanted to find a way to include Andy, who had bags of experience and never let us down when he played. His other options were more youthful, with Derek Parlane and Alfie Conn also in the running, and maybe he was leaning towards an older head on such a big occasion.

Derek was also one of a number trying to prove they were physically ready for Barcelona, after suffering a knock in the weeks leading up to the final.

At the end of a long season there were plenty of bumps, bruises and worse to contend with. Colin Jackson’s fitness was a worry after he had picked up a knee injury, and John Greig’s ankle knock was the other major concern. John made the trip to the Highlands and played away fine in a cameo from the bench. Colin had to sit it out.

He was probably the biggest injury worry, the one with the question mark over his head. He’d suffered ligament damage in the final weeks of the season, and it’s impossible with an injury like that to know how it is going to react. It can feel fine in fitness tests and the like, and then one twist or turn knocks it back a week or two. The clock was ticking.

That game at Inverness was a fortnight before the match in Barcelona, and it was a case of fine-tuning the squad.

The highest-profile omission from that list was not due to injury, it was down to the hard-line approach which typified Waddell as the man making those big calls.

Willie Henderson, so often a talisman for Rangers, would be watching from afar. His departure had been confirmed as the rest of us were preparing for the trip to Spain, one of the names on a list of players released. It was a low-key end to a career which had been anything but.

On the outside, I think there was surprise at the decision to let him go. The club had a three-year option on his contract, and he was a player known across the world. Inside, I don’t think any of us saw a different outcome once he and the manager had locked horns.

It was the end of a turbulent period. After being dropped into the reserves, he walked out and said he wouldn’t be back. When he did return, the manager suspended him for a month. They weren’t on each other’s Christmas card list it’s fair to say.

Willie quickly took up an offer to go out to South Africa with Durban City while he considered his options, during the same period we were packing our bags for Barcelona.

You might think it would have been a distraction for us, but in reality it has never been a business with much room for sentiment. Players come, players go. For those who remain it’s a case of on to the next challenge.

In our case that lay in the Highlands. We won the game in Inverness 5-2 and had a matching result six days later when we played St Mirren in the second and last of the warm-up games.

That was at Love Street – with an Alfie Conn hat-trick stealing the show. Would that have any bearing on the team selection in Spain? Maybe, just maybe.

A clutch of us played both of those games – myself, Sandy Jardine, Alex Macdonald, John Greig from the bench, Andy Penman, Colin Stein, Willie Johnston, Derek Johnstone and Derek Parlane. Another nod to the fact the manager was giving Andy and Derek a chance to play their way in, or was he indulging in a bit of kidology with the Russian scouts looking in from afar?

Tommy McLean had been sent home from training before the St Mirren game, suffering from a throat infection, and it was those little uncontrollable things that perhaps posed the biggest risk to the preparations. Something like that could easily have taken out half of the team if they hadn’t acted quickly.

With the manager out in Russia to watch Dynamo in a league match against Kairat, it was Willie Thornton in charge of us back in Paisley. Thornton was a real gent and a calming influence around the squad. I think Waddell appreciated his good counsel behind the scenes too.

St Mirren had apparently been asked to give us a tough test, although they took that brief to extremes with some of the tackles that were flying in. You got used to that as a Rangers player, but a few days before a European final wasn’t the time to be picking battles on the pitch.

In-between, we trained pretty much as normal, kept ticking over by the coaching staff. We should have been grateful for the recuperation time after a long season – we had played 59 competitive games up to that point – but as a player you don’t want to stop once you’re into that rhythm.

Match sharpness is so different from fitness. Yes, we could keep ourselves in shape during that extended downtime, but staying tuned in was far more difficult.

The two friendlies served a purpose, but with nothing at stake it’s a very different proposition to playing in competitive fixtures. With the season over for everyone else, there also wasn’t a queue of opposition teams lining up for extra games. Most teams were demob happy, and the fact we had any games at all was fortunate.

While we were at home trying to stay in shape, the manager had completed his trip to Russia to see the opposition in the flesh and had touched down in Spain to make a final check on our base out there. It was typical of his attention to detail and the desire to be in control of every facet.

Finding out about the opposition we were about to face wasn’t a simple task, not like in previous ties against the likes of Bayern Munich of Germany and Torino of Italy.

It’s easy to forget that European football was still in its infancy really, particularly for some of the club sides we found ourselves competing against during my time at Rangers and certainly for Dynamo.

Soviet teams had joined as part of the expansion of the UEFA competitions and had only five or six years under their belts by the time the men from Moscow made it to Barcelona in 1972. They had the distinction of becoming the first team from what was then the USSR to reach a final, but it was another three years until there was a winner, with Dynamo Kiev beating Hungarian opposition in the form of Ferencvaros.

Dinamo Tbilisi went on to beat German side Carl Zeiss Jena in 1981, and Dynamo Kiev beat Atletico Madrid in the 1986 final to complete a hat-trick.

Dynamo Moscow, in our era, were the big hitters along with their city rivals Spartak. There was always said to be a connection with the secret police, stretching back long before we played them.

There was also a story behind the blue-and-white kit, which could be traced back to their formation under Harry Charnock. As the name suggests, it was an Englishman rather than a Muscovite who set up the club, and as a Blackburn Rovers supporter he went for colours which reminded him of home.

He and his brothers had moved out to work in the cotton industry with their father and launched a works team that went on to become a giant of the game in their adopted country. Apparently, the idea was to persuade the factory staff to refrain from drinking vodka and play football instead, and so the Orekhovo Sports Club was born. It sounds like a plan that couldn’t possibly fail.

They fled the country in 1919 after the Russian Revolution, and the team, which had enjoyed plenty of success, was taken over by the head of the Cheka – the country’s first secret police force, before the KGB – and renamed Dynamo Moscow.

And there ends the history lesson!

They went on to win a string of league titles, particularly in the early days, and were still a force to be reckoned with in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. They’ve yet to reach another European final though.

Then, and now, their biggest claim to fame is as the home to Lev Yashin. He was the poster boy of Russian football, spending his entire playing career with Dynamo, all 20 years of it, and is still the only goalkeeper ever to win the Ballon d’Or. We saw very little of him playing for his club, other than the rare forays to Britain for exhibition games, but everyone was aware of the legend that was Yashin from his World Cup and international exploits. He was a goalkeeper who did things with style.

Thankfully, by ’72 he had packed away his gloves and was confined to the sidelines, still attached to the club and part of the backroom team for the final. Even though he wasn’t going to be on the park, he gave Dynamo star quality and was the main focus of media attention when it came to Moscow.

As for the team we were going to face, they were largely unknown in the West – but we could rely on Waddell to keep us right.

Even when he had to go behind the Iron Curtain, he was able to furnish us with the usual pen pictures and every bit of information you could ever want on the opposition. No stone was left unturned, there was never any room left for excuses.

Waddell had dedicated himself to the coaching profession. He had travelled to Italy in the early 1960s to study the methods of Internazionale’s Helenio Herrera, an Argentine master of his craft who won the European Cup twice with Inter. Legend has it that he slept next to a model of a football pitch, and it wouldn’t surprise me if Waddell kept a tactics board on his bedside table too.

By the time we set off for Barcelona it was pretty much over to us as players. The manager’s preparation had been done long before we arrived.

The departure was all part of the big build-up, with the official Rangers party piped onto the plane and given a formal send-off by Glasgow’s Lord Provost John Mains.

The hype had been building through the week. I even had photographers out at the house to get shots of me packing my boots for the trip.

We flew out from Prestwick on the Sunday, travelling down from Ibrox by coach. You had players parking at the ground, some being dropped at the door and others walking up from the subway to gather together with bags in hand like an excitable class gathering for a school trip.

Our wives were part of the travelling contingent but flew out separately and were whisked away to stay in Sitges courtesy of the club while we headed for our base at Castelldefels, south of the city on the Costa del Garraf. The Gran Hotel Rey Don Jaime was to be home for the days ahead, perched on a hillside and away from prying eyes.

It was a quiet coastal hideaway in those days, and suited us perfectly. Since then, it has quadrupled in size – not quite the sleepy hollow it once was and there’s a bit more of a sprinkling of stardust. Now it is home to the likes of Lionel Messi. It’s good to know that he’s chosen to follow in the footsteps of football legends.

We travelled with a big squad, for that era at least. The back-up goalkeepers Bobby Watson and Gerry Neef were included as cover for Peter McCloy, and there were plenty of outfield options, which proved to be important.

There was a sense of kid gloves around us once we reached Castelldefels. We wore tracksuits rather than shorts by the pool, to guard against sunburn, and we took our own provisions with us, as we had done frequently on European trips, in a nod to the manager’s fears about stomach upsets. A hamper full of Aberdeen Angus wasn’t unusual in the hold of our charter planes – high steaks, you might say! Without giving too much away, I’m afraid the jokes don’t get much better.

From the moment we landed in Barcelona we got a sense of how big a support had made the journey. It felt like there were Rangers fans around every corner. The airport was a sea of red, white and blue. Hats, scarfs, jackets, kilts and even berets. You name it, the colours were everywhere, and Barcelona belonged to Rangers.

TWO

‘YOU COULD DARE TO DREAM’

THAT FLIGHT TO Barcelona was the end of a far longer journey for me. From the muddy playing fields of Aberdeen to the hallowed turf of the Nou Camp, there had been a few bends in the road to navigate.

Every one of us had followed our own path, and to get under the skin of ’72 you have to rewind further back, back to where it all began.

From 1 to 11 we came from different cities and towns, with different backgrounds and different stories. The one thing in common was the love of football which started as soon as we could kick a ball. No TV cameras, no crowds – just the adrenaline rush of beating a man or scoring a goal. We didn’t know it then, but that is what we’d spend our lives chasing and the same thing that drove us on every time the going got tough on that run to Barcelona.

For me football was in the blood. A bit of a cliché? Maybe, but I think the Smiths have as genuine a claim to that as anyone.

My dad, Jimmy, was an all-round sportsman, an excellent tennis player and no stranger to the football field. He played junior football with Woodside and was part of the team from Aberdeen that won the Newlands Cup, run by the National Dock Labour Board and contested by harbour works teams from across Britain.

On my mum Margaret’s side, my two uncles were good players at a decent level. Alex Baigrie started out at Aberdeen and played with Forres Mechanics in the Highland League. Hugh Baigrie also cut his teeth in the juniors in Aberdeen, another Woodside player in the family, before being tempted south by Partick Thistle in the pre-war days. He also turned out for Ayr and Montrose and based himself in Glasgow after he hung up his boots. I would stay with him in Springhill after I made the move to Rangers, while I was still commuting from the North-east.

My cousin Hughie Hay, another on my mum’s side, was probably the most notable of the elder footballing statesmen in the family and the one I remember playing, just 12 years my senior. He progressed from Banks o’ Dee in junior football to Aberdeen early in the 1950s and was destined for great things before a leg break during his national service got in the way. It meant he missed the Dons’ title-winning season in 1954/55 and he never properly got going after that, playing out his career with Dundee United and Arbroath. It was a formidable Aberdeen team at that time, winning the league and cups, and I remember being part of some huge crowds at Pittodrie as a young boy.

The game ran through to the next generation.

My brother Doug, six years my senior, was the first to shine. Doug grew to become what I would describe as the perfect centre-half – good in the air, a brilliant reader of the game, sharp in the tackle and a very intelligent user of the ball.