Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

For those old enough to remember, the Ryder Cups before the 1980s were often dispiriting affairs, especially if you were British. The Americans were simply too good and the British won only very occasionally. At the end of the 1970s, the great American golfer, Jack Nicklaus, suggested that the British invite golfers from Europe to join their team. Seve Ballesteros from Spain and Bernhard Langer from Germany were just coming to the peak of their careers and it was an inspired suggestion that fortunately the British accepted. The contest became more even and the Europeans began to win as often as the Americans. Indeed, since 1981 Europe has won ten of the sixteen contests. There have been many close and exciting contests with huge dramas developing on the last day. Standing out are the matches at Brookline in 1999 when the Americans overturned a deficit of 10-6 going into the final day; Celtic Manor in 2010, when the Americans nearly, but not quite, overturned a substantial European lead; and finally at Medinah in 2012 when the Americans were cruising comfortably to victory on Saturday afternoon with a 10-4 lead, only for the Europeans to fight back: first by winning the last two fourballs on the Saturday and then winning 8Ω points out of 12 in the singles on Sunday. The Ryder Cup captures all the glory of golf's greatest match.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This updated edition publishedin the UK in 2012 by Corinthian Books, an imprint ofIcon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,39–41 North Road, London N7 9DPemail: [email protected]

Previously published in the UK in 2010 by Corinthian Books

Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asiaby Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,74–77 Great Russell Street,London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asiaby TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Published in Australia in 2012by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in Canada by Penguin Books Canada,90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3

ISBN: 978-190685-058-6

Text copyright © 2010, 2012 Peter Pugh and Henry Lord

The authors have asserted their moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

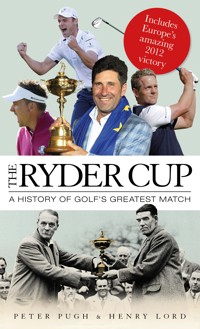

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

About the Authors

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

1. Reasonably Even

A Stuttering Start: Gleneagles 1921 and Wentworth 1926

Adequate Money Must be Found: Worcester, Massachusetts 1927

‘Smell the Flowers’: Walter Hagen

Must be Native-Born: Moortown 1929

Henry Cotton Left Out: Scioto, Columbus 1931

The Tough Taylor: Southport and Ainsdale 1933

The Americans are Better: Ridgewood, New Jersey 1935

‘Win on Home Soil’: Southport and Ainsdale 1937

2. Americans almost completely dominant

Still the Putting that Counts: Portland, Oregon 1947

The ‘Wee Ice Mon’: Ganton, Yorkshire 1949

Little Hope of Victory: Pinehurst, North Carolina 1951

‘The Melancholy Fact was . . .’: Wentworth, Surrey 1953

‘Better than Ever Before’: Thunderbird, Palm Springs, California 1955

‘You could have Knocked us Down with a Feather’: Lindrick, Yorkshire 1957

Crushed Again: Eldorado, Palm Springs, California 1959

3. Is this match worth playing?

Must have the Captain in Control: Royal Lytham 1961

Must Include Fourballs: Eastlake, Atlanta 1963

The American Short Game is Still Superior: Royal Birkdale 1965

‘The Finest Golfers in the World’: Champions, Houston 1967

‘I Don’t Think You would have Missed that Putt, Tony’: Royal Birkdale 1969

4. ‘Something has to be done to make it more of a match’

Same Old Story: Old Warson, St Louis 1971

Change of Format, Same Result: Muirfield 1973

‘Well Done, Barnesy’: Laurel Valley, Pennsylvania 1975

Faldo on the Scene: Royal Lytham 1977

Bring in the Europeans: The Greenbrier, West Virginia 1979

Jacklin was Insulted: Walton Heath 1981

5. The Tony Jacklin Era

‘This wasn’t a Loss’: Palm Beach Gardens, Florida 1983

‘I Didn’t Come the Heavy Stuff’: The Belfry 1985

Superior Golf from the Europeans: Muirfield Village 1987

‘Spectators Clapping us All the Way’: The Belfry 1989

6. Over to you, Bernard

‘War on the Shore’: Kiawah Island 1991

‘I had to Split Up Two Winning Partnerships’: The Belfry 1993

‘I Tried to Keep the Pressure on the Golf Course’: Oak Hill, Rochester 1995

7. The irrepressible Seve

‘I Tried to Get to the Tee Before they Drove’: Valderrama 1997

The Bear Pit at Brookline: Brookline, Boston, Massachusetts 1999

8. Torrance and Langer do their homework

‘Tell ’Em Who I Beat’: The Belfry 2002

Woods Struggles to Care: Oakland Hills 2004

9. ‘The reception is something I will never forget’

10. Azinger’s rampaging camaraderie

11. ‘This is the greatest Ryder Cup ever’Celtic Manor Resort, Newport, Wales 2010

Fifty Per Cent of the Team were Rookies

Not Enough Passion

Plenty of Tension to Come

‘This is the Greatest Ryder Cup Ever’

12. The Miracle at MedinahMedinah Country Club, Chicago, Illinois, 2012

It’s Going to be Close

The American Rookies have a Good First Day

Another Good Day for the Americans

‘Hang About, We still have a Chance’

‘The Greatest Sporting Occasion I have Seen’

Appendix: Full Record of Matches

Plates

About the Authors

PETER PUGH was educated at Oundle and Cambridge, where he was a member of the golf team. He has written many books on golf and golf clubs as well as about 50 company histories, including The Magic of a Name, a three-volume history of Rolls-Royce.

HENRY LORD is the co-author of the highly acclaimed Creating Classics: The Golf Courses of Harry Colt (Icon, 2008), Masters of Design: Great Courses of Colt, MacKenzie, Alison and Morrison (Icon, 2009), and St Andrews: The Home of Golf (Corinthian, 2010), which includes a foreword from the great Ryder Cup player and captain, Seve Ballesteros.

List of illustrations

1. The Great Britain Ryder Cup team in 1929

2. Fred Daly, the Open Champion and Charlie Ward discuss the larger American ball that they used in the match between Great Britain and the Oxford and Cambridge Golfing Society before the 1947 Ryder Cup so that they could get used to it

3. The Great Britain team at Waterloo station before leaving for the 1947 match

4. Sam Snead drives at the 5th at Ganton watched by Charlie Ward in the 1949 match

5. Great Britain’s Bernard Hunt driving in the 1953 match at Wentworth.

6. Great Britain’s Eric Brown drives from the 3rd tee on his way to victory at Lindrick in 1957

7. Captain Dai Rees held aloft by Bernard Hunt and Ken Bousfield following the British victory at Lindrick in 1957, the first British victory for 24 years

8. Peter Alliss and Christy O’Connor in the 1965 Ryder Cup match at Royal Birkdale

9. The 1969 match at Royal Birkdale finished in an exciting draw as Jack Nicklaus conceded a two-and-a-half-foot putt to Tony Jacklin on the final green

10. Jack Nicklaus driving in his match against Maurice Bembridge in the 1973 Ryder Cup at Muirfield

11. Brian Barnes and Bernard Gallacher look on disconsolately as the Americans win another match at Royal Lytham in 1977

12. Peter Oosterhuis and a young Nick Faldo just after they had beaten Jack Nicklaus and Ray Floyd at Royal Lytham in 1977

13. Nicklaus advises Tom Watson in their match against Bernhard Langer and Manuel Pinero at Walton Heath in 1981

14. Sam Torrance has the honour of holing the putt that brings Europe its first Ryder Cup victory at The Belfry in 1985

15. The European team celebrate their famous victory at The Belfry in 1985

16. Seve Ballesteros making a point to captain Tony Jacklin and Mark James in the 1989 match at The Belfry

17. Christy O’Connor Jr. celebrates as his putt on the 18th retains the Ryder Cup for the European team at The Belfry in 1989

18. Seve Ballesteros asks the crowd to move so that his teammate, José María Olazábal, can hit his shot during the sometimes ill-tempered match at Kiawah Island in 1991

19. Bernhard Langer and Hale Irwin on the 17th green in their tense deciding match at Kiawah Island in 1991

20. Nick Faldo plays to the famous 10th green during the 1993 match at The Belfry

21. Bernhard Langer holes his putt to win his singles match in the 1995 match at Oak Hill

22. Philip Walton splashes out of a bunker in his match at Oak Hill

23. Nick Faldo and captain Seve Ballesteros at the 1997 match at Valderrama

24. Crowd control at the 1999 match at Brookline was a disgrace

25. Europe’s Philip Price sinks a vital putt on the 16th in his unexpected victory over Phil Mickelson at The Belfry in 2002

26. Paul Azinger and Tiger Woods during their fourball defeat by Darren Clarke and Thomas Björn at The Belfry in 2002

27. Captains Bernhard Langer and Hal Sutton on the 1st tee at Oakland Hills during the 2004 match

28. Europe’s Colin Montgomerie celebrates a vital putt during the 2004 match at Oakland Hills

29. Lee Westwood studies his line while partner Darren Clarke looks on in the 2006 match at The K Club

30. US captain Tom Lehman consoles Jim Furyk after his 2 and 1 defeat by Paul Casey in the 2006 match at The K Club

31. Europe’s Oliver Wilson celebrates his winning putt in his foursomes match partnering Henrik Stenson against Phil Mickelson and Anthony Kim in the 2008 match at Valhalla

32. European captain Nick Faldo, holding the Ryder Cup, meets US captain Paul Azinger before the 2008 match

33. USA’s Stewart Cink watched by Europe’s Rory McIlroy at Celtic Manor, Newport in 2010

34. USA’s Tiger Woods chips on the 18th during the first fourball round at Celtic Manor

35. Europe’s Ian Poulter and Martin Kaymer line up a putt on the 12th green at Celtic Manor

36. Europe’s Edoardo Molinari celebrates with fans on the 17th green after the 2010 Ryder Cup is won

37. Europe’s Graeme McDowell after his singles win in 2010 clinches victory for Europe

38. The victorious 2010 European team pose for photographers on Celtic Manor’s first fairway with the Ryder Cup trophy

39. European team captain José María Olazábal wipes away a tear as his late friend Seve Ballesteros is remembered during the opening ceremony at the Medinah Country Club in 2012

40. USA’s Keegan Bradley congratulates Phil Mickelson after Mickelson made a putt to win the 13th hole during a foursomes match at Medinah

41. USA’s Bubba Watson hits out of the rough on Medinah’s fourth hole during a fourball match in 2012

42. Europe’s Rory McIlroy and Graeme McDowell cross the bridge at Medinah’s 14th hole during a fourball match in 2012

43. Darren Clarke congratulates USA’s Phil Mickelson and Keegan Bradley on the 13th hole after a foursomes match at Medinah in 2012

44. European players celebrate as Ian Poulter makes a putt to win on the 18th hole during a fourball match at Medinah in 2012

45. Martin Kaymer celebrates after ensuring that Europe retains the Ryder Cup trophy in 2012

46. USA’s Jim Furyk can hardly believe it as he and his team watch their lead evaporate on the final day of the 2012 contest

47, 48. European players celebrate after pulling off ‘the miracle at Medinah’

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Oliver Pugh for his cover design and selection of photographs for chapters 11 and 12, and the editorial team at Icon Books.

Chapter 1

Reasonably Even

A stuttering start

Gleneagles 1921 and Wentworth 1926

Adequate money must be found

Worcester, Massachusetts 1927

‘Smell the flowers’

Walter Hagen

Must be native-born

Moortown 1929

Henry Cotton left out

Scioto, Columbus 1931

The tough Taylor

Southport and Ainsdale 1933

The Americans are better

Ridgewood, New Jersey 1935

‘Win on home soil’

Southport and Ainsdale 1937

A stuttering start

The original idea for a match between the professional golfers of Great Britain and the United States probably came from the Ohio businessman Sylvanus P. Jermain. He enthused the great Walter Hagen while James Harnett, circulation manager of Golf Illustrated, gave his backing too. They, along with the United States Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA), encountered some problems raising the money and there was also some argument about who would be eligible to play. Was it to be only professionals born in the USA, or could European-born players be picked too? Eventually, with each player given $1,000 to cover his expenses, a team was sent to play the match on the newly opened King’s Course at Gleneagles in June 1921.

The match was played alongside the Glasgow Herald 1,000 Guineas Tournament and, by comparison, attracted little public enthusiasm; once the crowds had seen George Duncan pick up the £160 (about £10,000 in today’s money) prize, they went home and failed to return for the Great Britain vs. USA match. For the record, the home side won by nine points to three with three matches halved. No one seemed to think there should be a follow-up match.

Enter Samuel Ryder and his younger brother, James. In St Albans, Hertfordshire, the brothers had built up a successful business selling packets of seed for a penny each through the post. A workaholic but also a good local community man as well as a devoted Christian, Sam Ryder was advised by his church minister to play golf for exercise and relaxation. He began to play at the age of 50 and, in true thorough Ryder style, paid the local club professional in 1901 to come to his house six days a week to give him lessons. Within a year he was good enough to join the local club, Verulam, and within another year was elected Captain.

In the early 1920s Ryder’s business, the Heath and Heather Company, sponsored professional tournaments; in one, held at the Verulam, he paid every player a £5 appearance fee. That is about £300 in today’s money but even so, it seems paltry by today’s standards. At the time, though, it was so novel that everyone was staggered. The winner would receive £50, which was only £5 less than the winner of the Open received. It was all good enough to attract the top players including Harry Vardon, James Braid, George Duncan, Sandy Herd and the eventual winner, Arthur Havers. Also competing was Abe Mitchell, the professional at North Foreland in Kent.

Ryder and Mitchell became friends and Ryder contracted Mitchell at a then-generous fee of £500 a year (about £30,000 in today’s money) to become his personal tutor. Mitchell increased Ryder’s interest in the professional game and when the opportunity for a Great Britain match against the USA arose again, Ryder wanted to be involved.

In early 1926 the British sent an invitation to their American counterparts to take part in a match at Wentworth before their attempted qualification for the Open Championship at nearby Sunningdale. On 26 April the newspapers announced that:

Mr S. Ryder, of St Albans, has presented a trophy for annual competitions between teams of British and American professionals. The first match for the trophy is to take place at Wentworth on June 4th and 5th.

When the match took placed at Wentworth on 4 and 5 June 1926, the strong Great Britain team won easily. Even the masterly Walter Hagen was convincingly beaten 6 and 5 by George Duncan. Abe Mitchell beat Jim Barnes by 8 and 7. However, the match was not deemed to be an official match. Golf Illustrated explained it like this:

Owing to the uncertainty of the situation following the [General] Strike in which it was not known until a few days ago how many American professionals would be visiting Great Britain, Mr J. Ryder decided to withhold the cup, which he has offered for annual competition [note the ‘annual’] between the professionals of Great Britain and America. Under the circumstances the Wentworth Club provided the British players with gold medals to mark the inauguration of the great international match.

And indeed, as a result of the strike several Americans did not travel. Rather than cancel the match, Ryder invited a number of non-Americans to make up their team. As a result, the US PGA refused to sanction the match as the first ‘official’ Ryder Cup match.

Adequate money must be found

Finally, all seemed set fair for a proper start when a match was arranged to take place at the Worcester Country Club in Massachusetts in June 1927. However, all was not yet sweetness and light.

It is difficult to believe now when golf clubs are very proud of their professional if he is a tournament player or, better still, he is selected for the Ryder Cup team, but in the 1920s British clubs were reluctant to let their professional have the time off to participate in the match, especially if it was held in the USA. Then there was the question of money. Even travelling second class by sea, the cost was more than the PGA could afford.

George Philpot, editor of Golf Illustrated, launched an appeal for £3,000 (about £180,000 in today’s money). He wrote to every golf club and backed this up with a strong request for support in his magazine:

I want the appeal to be successful because it will give British pros a chance to avenge the defeats, which have been administered by the American pros while visiting our shores in search of Open Championship honours. I know that, given a fair chance, our fellows can and will bring back the Cup from America. But they must have a fair chance, which means that adequate money must be found to finance the trip. Can the money be found? The answer rests with the British golfing public.

The appeal was spectacularly unsuccessful and Philpot wrote scathingly, also in his magazine:

It is disappointing that the indifference or selfishness of the multitude of golfers should have been so marked that what they could have done with ease, has been imposed on a small number. Of the 1,750 clubs in the British Isles whose co-operation was invited, only 216 have accorded help. It is a deplorable reflection on the attitude of the average golfer towards the game.

In the end, with the donations from the clubs and from Canada, Australia, Nigeria and even the United States, plus £100 from Sam Ryder, they were still £500 short of the target. Philpot put in £500 (£30,000 in today’s money) of his own and was appointed team manager.

Another serious problem arose when, just before the team were due to sail from Southampton, Abe Mitchell, the team captain and probably their best player, was struck down with appendicitis.

The next problem was the rough passage the team endured crossing the Atlantic. Finally, when they arrived, feeling very out-of-sorts, in New York, they were dismayed to find that Walter Hagen had organised a big reception for them. Arthur Havers, the 1923 Open champion, would say later:

The whole thing about going to America was a culture shock for most of us. When we got to New York, the entire team and official were whisked through without bothering with customs and immigration formalities.

There was a fleet of limousines waiting for us at the dockside, and, with police outriders flanking us with their sirens at full blast, we sped through New York. Traffic was halted to let us through; it was a whole new world for us. Everywhere we went we were overwhelmed with the hospitality and kindness of the Americans.

Suddenly we were in a world of luxury and plenty, so different from home . . . Even the clubhouses were luxurious with deep-pile carpets, not like the rundown and shabby clubhouses at home, which was all most of us really knew.

And the lavish entertainment continued. The British party were taken to the Westchester-Biltmore Country Club for a gala dinner and after a long night went to the Yankee Stadium to see Babe Ruth’s New York Yankees play the Washington Senators. Hagen offered them another night on the town but they declined and staggered off to their hotel.

Eventually, the British team got down to practice but some, especially George Gadd, did not recover well from the rough sea passage and then, out of the blue, on the eve of the match, the Americans requested alterations to the playing format. They wanted four changes:

George Philpot was outraged by these last-minute requests and conceded only the point about the substitutes.

As it turned out, the Americans need not have worried about the ‘Scotch’ foursomes, as they won them 3–1 and indeed crushed the British team throughout the match with the final score 9½–2½. The real difference between the two teams was their performance on the greens.

Bernard Darwin, the best writer on golf in the twentieth century, wrote in The Times:

The British team played well enough through the green, but on the putting greens there was a marked inferiority about the visiting team.

Ted Ray, who had been appointed Captain when Mitchell fell ill, told the Daily Express:

Our opponents beat us fairly and squarely and almost entirely through their astonishing work on the putting greens, up to which point the British players were equally good. We were very poor by comparison, although quite equal to the recognised two putts per green standard. I consider we can never hope to beat the Americans unless we learn to putt. This lesson should be taken to heart by British golfers.

‘Smell the flowers’

At this point, not only did the Americans have the better golfers but they were also leading the way in establishing the top golf professionals as significant, and potentially wealthy, members of society. No one epitomised this development more than Walter Hagen. Golf professionals in Britain were often not allowed to enter the clubhouse by the front door; indeed, at the Open Championship at Deal in 1920 Hagen hired a footman and a Rolls-Royce to serve as his dressing room because he was refused entrance to the clubhouse changing room. Having won the US Open in 1914 and 1919, Hagen soon realised he could make more money playing in exhibition matches than he could in tournaments and between 1914 and 1941 he played in no fewer than 4,000, earning around $1 million. However, he always maintained that money was not important to him, saying that he didn’t want to be a millionaire; he just wanted to live like one. Another of his favourite sayings was:

I never hurry. I never worry. Always stop to smell the flowers along the way. It’s later than you think.

As well as making money in exhibitions he was also one of the first to make significant money endorsing golf equipment – in his case, Wilson Sports, who produced some of the first matched sets of irons and named them after him: ‘Walter Hagen’, or ‘Haig Ultra’.

He was also well known for his dashing wardrobe of tailored clothes in bright colours and the result was the nickname ‘Sir Walter’. Altogether he did much to raise the status – and the earnings – of golf professionals in the USA. Gene Sarazen would say of him:

All the professionals . . . should say a silent thanks to Walter Hagen each time they stretch a check between their fingers. It was Walter who made professional golf what it is.

The strange thing was that he hit a lot of erratic shots, but his powers of recovery were second-to-none and his short game was superior to anyone’s. No one else did more to prove the saying: ‘Drive for show, putt for dough’. Hagen never allowed pressure to get to him. On the eve of the final match of the 1926 PGA Championship, when he was out on the town, he was told that his opponent, Leo Diegel, was already in bed. He replied: ‘Yeah, but he ain’t sleeping.’

This calm approach earned him eleven major titles, more than anyone else except Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods, and we should bear in mind that the Masters did not exist when he was at his peak, between 1913 and 1930.

Must be native-born

There was some controversy before the second Ryder Cup match which was to be played at Moortown Golf Club, near Leeds, on 26 and 27 April 1929. Sam Ryder decreed that all participants must be native-born citizens of the countries they were representing.

This weakened the US team and Hagen announced before the matches that ‘foreign-born’ players would be picked for the US team. He made the point that they had been allowed to fight in the war for their newly adopted country, so surely they could be picked to play golf for it too.

The British team was considerably stronger than the one that had been thrashed two years earlier. Abe Mitchell was back and there were three new up-and-coming professionals; Henry Cotton, Stewart Burns and Ernest Whitcombe. Ray, Havers and Jolly were dropped and only Charlie Whitcombe, Fred Robson and Archie Compston survived from the earlier team. However, the British team were still dogged by a lack of money. The golfing public had still not cottoned on to the match as more than a glorified exhibition; a new Golf Illustrated appeal raised only the paltry sum of £806 (less than £50,000 in today’s money).

Once the Americans arrived their main problem was not an enthusiastic reception, as had been the case with the British team in New York, but the foul British weather. The practice days at Moortown were wet and cold with a strong wind. Added to this, the Americans were not allowed to use the steel shafts that they had been using for the last three years. The Rules Committee at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club had refused to legalise them in Great Britain. The Americans had no choice but to revert to hickory shafts.

Fortunately for the Americans, the weather relented a bit on the opening day of the match. It was still very cold but the rain stopped and the strong wind gave way to a light breeze. For the first time the golfing public turned up in big numbers to watch the matches. The results of the foursomes were disappointing for Great Britain as they lost two matches and halved one (where they were one up with one to play). The only British winners were Abe Mitchell (Sam Ryder, in the crowd, will have been very pleased about that) and Fred Robson who, after being all square at lunch, beat Gene Sarazen and Ed Dudley 2 and 1.

For the singles on the second day, British captain George Duncan found himself playing none other than ‘Sir’ Walter Hagen. Duncan had beaten Hagen in the first unofficial match at Wentworth in 1926 and, whatever Hagen’s achievements in stroke-play tournaments, felt he would continue to beat him in matchplay. For his part Hagen is supposed to have said to his team when he discovered he was playing Duncan: ‘Well boys, there’s a point for our team right there.’

But then, Hagen always liked making remarks like that (he is the golfer who is supposed to have said when he turned up for one of the Majors: ‘Who’s coming second?’).

The story continues in that Duncan is said to have heard this remark and, thus goaded, played the golf of his life. He completed the first eighteen holes in 69 and eventually won by a staggering 10 and 8; this against a man who was a superb match player. (Nor was Hagen any slouch when it came to stroke-play, as he demonstrated when he won the Open Championship by six clear shots a few weeks later.)

Born in September 1883 in Methlick, Aberdeenshire, George Duncan was apprenticed as a carpenter. A great all-round sportsman, he turned down an offer to become a professional footballer with Aberdeen and became a professional golfer instead. He won the first post-First World War Open Championship at Royal Cinque Ports in 1920. He also came close to winning the 1922 Open after a magnificent round of 69, which at the time was only the third-ever round under 70 in the Open. In the final round he fluffed a chip from what became known as ‘Duncan’s Hollow’ in front of the 18th green and lost to Walter Hagen by a stroke.

He gained some sort of revenge by beating Hagen 6 and 5 in the match at Wentworth in 1926 in what was (but, as we have seen, was not officially) the first Ryder Cup match and then again at Southport in 1929 following Hagen’s goading remark about him securing a certain point for the Americans when he learnt he was playing Hagen.

Duly inspired, the British produced four more victories and a half and won the match 7–5.

The large crowd had become very enthusiastic in support of their team and Bernard Darwin felt compelled to write in The Times:

It was a crowd that did not, I imagine, know a great deal about golf. While realising that golf does not give so many opportunities of shouting as football, they were resolved to make the difference between the two games as small as possible. So they ran, cheered and once, I’m afraid to say, forgot themselves so far as to cheer when an American missed a short putt.

Darwin also wrote in The Times:

The Americans fought back with a cheerful gallantry that could not be surpassed; they never gave in and never grudged a victory, but, for once in a very long while, they were the underdogs, and they struggled in vain.

Henry Cotton left out

Controversy was – and still is – never far away in Ryder Cup matches and Great Britain shot themselves in the foot for the next match which was to be played at Scioto Country Club, Columbus, Ohio on 26 and 27 June 1931. They decided that all of their team had not only to be born in Britain, but also resident in Britain. This ruled out three of their best young players – Henry Cotton, Percy Alliss who was the professional at Wannsee Golf Club in Berlin, and Aubrey Boomer who was at St Cloud in Paris.

Cotton began an acrimonious discussion – the first of many – with the PGA about their insistence, agreed with the US PGA, that all the team return to Britain immediately after the match. Furthermore, the PGA wanted all money earned in exhibition matches to be shared equally among the team. Cotton disagreed with both rulings and wrote an article for Golf Illustrated in which he said:

It was pointed out to me that if I enjoyed the benefit of a free passage, it was not fair for me to use that benefit for my personal gain by staying after the team had returned and playing as a free lance. It was this that caused me to intimate to the Professional Golfers’ Association that I was quite prepared to pay my passage out and back. Here again the Association found my suggestion unacceptable.

Cotton went further and asked Alliss and Boomer to join him in a private tour to the USA. Alliss agreed, and he and Cotton planned to appear at Scioto during the match. In spite of this provocation the PGA were very keen for Cotton to play for the British team and said that, if he wrote a letter of apology, they would overlook his behaviour. Cotton refused and consequently the British team was weaker than it could have been.

Meanwhile in the USA, for the first time the US PGA organised a qualifying tournament. The committee had already picked Hagen, Sarazen, Farrell, Espinosa and Diegel but thirteen others had to play a gruelling 90 holes to try to secure one of the remaining four places.

When the day arrived, in marked contrast to the freezing temperatures of Moortown two years earlier the temperature was 100°F (almost 38°C). This would affect the British as badly as the cold weather at Moortown had the Americans. As it turned out, the British team was outplayed from start to finish. The foursomes were lost 3–1, with only Abe Mitchell and Fred Robson earning a point by beating Leo Diegel and Whiffy Cox 3 and 1. On the second day, the heat did not relent and Britain lost the singles 6–2 to give an overall result of USA 9, Great Britain 3.

Inevitably there was much criticism of the team and of the PGA for leaving out Cotton, Alliss and Aubrey Boomer, though some of the more thoughtful appreciated that the conditions had been almost impossible for the British team. One journalist wrote:

It is unkind to hit a man when he is down . . . Nevertheless, one must regret that Charles Whitcombe was so modest as to leave himself out of the Foursomes and so charitable as to play Duncan at all. Duncan has been a very great golfer, but he is not one now, and why should it be pretended that he is?

The PGA moved that never again should the match be played at the height of the American summer and, fortunately, the US PGA agreed. As we shall see, the 1933 match at Ringwood, New Jersey, was played in September.

The tough Taylor

For the 1933 match to be held on 26 and 27 June 1933, at Southport and Ainsdale, the PGA was determined to make a fresh start after the debacle of 1931 and elected the first non-playing captain, five times Open winner John Henry Taylor. Taylor was a renowned disciplinarian (he had initially pursued a military career) and he first tackled the question of players such as Cotton, Alliss and Boomer and their overseas residency. Alliss had returned to Britain so he was available, but Cotton was at the Royal Waterloo Club in Belgium and Boomer was still in France.

Some wanted to amend Sam Ryder’s trust deed but both Taylor and the PGA were adamant that the rules would not be changed to accommodate Cotton and Boomer. Noting how unfit the British team had been in 1931, Taylor recruited a physical fitness expert from the British Army, Lieutenant Alick Stark. He decreed early morning runs along Southport beach as well as rub-downs to loosen up the golfers’ muscles. Taylor, at 62 years old, set a good example by running alongside the golfers.

For their part the Americans brought what Bernard Darwin noted in The Times was ‘a very strong side, if anything stronger than that which our men so gloriously defeated on that freezing day at Moortown’.

As ever, there was some controversy when the laid-back Hagen (retained as the US captain) failed to turn up to exchange teams’ orders at the first two times arranged with Taylor. The tough Taylor refused to be disorientated by this gamesmanship and sent a message to Hagen that if he failed to show at the third arranged tie the match was off. Hagen showed up and the match began.

For once the British performed well in the foursomes and led 2½–1½ at the end of the first day. Scenting victory, and probably learning that the popular Prince of Wales was a spectator, a 15,000-strong crowd turned up for the singles. Just as at Moortown, there was some less than sporting behaviour from sections of the crowd who cheered errant shots and missed putts by the Americans. Gene Sarazen would later complain that the atmosphere was more like that of a fairground than a golf course.

And Bernard Darwin of The Times wrote:

Golf was originally a game for the few, played on remote open spaces in decorous silence. But the world is too well used now to the popularity of games to be surprised that a great golf match should be treated almost like a great match in league football.

The gentleman on the megaphone harangued the crowd, introducing it to novel topics, the danger of tumbling on slippery grass and the presence of pickpockets. This last seemed prophetic for in the match between Hagen and Lacey a perfectly innocent spectator picked up Lacey’s ball in the rough and had to be pursued and brought back by an army of stewards armed with lances bearing red and white flags.

The excitement certainly built. At lunch time, the singles were all square and thus Britain was still one point ahead overall. The Americans soon put the teams level when Sarazen beat Alf Padgham 6 and 4 in the top match. This was something of a surprise because it was reckoned that Hagen had put Sarazen top as a sacrificial lamb. Most knew that the urbane Hagen and the tough Sarazen, of Italian extraction, did not see eye to eye. Hagen had in fact paired himself with Sarazen in the foursomes in order to quash rumours of a feud, but then lost no opportunity to blame him when they secured only a half.

Further down, matches swung to and fro. The ageing Abe Mitchell won but shortly afterwards Hagen and Wood both won, and with four matches still to be decided, the Americans were now one point ahead overall. First, Alliss won, so the teams were all square with three matches to go. Then Havers beat Diegel so the Brits were one ahead again. But then Charlie Whitcombe lost, so back to all-square with one match to go.

Syd Easterbrook and Densmore Shute came to the last hole all-square. It could not be closer. Both were bunkered off the tee. Easterbrook played safe out of the bunker while Shute bravely went for the green and was bunkered again. After their third shots both were on the green and both about twelve feet from the pin. Apparently Hagen was going to advise Shute to play safe because a half would mean the USA, the current holder, would retain the Cup. However, he was standing next to the Prince of Wales and thought it would be discourteous to move, so stayed where he was. Shute went for the hole, missed and finished about six feet past it. The nervous Easterbrook did not go for broke and finished about four feet short. Shute putted and missed. Easterbrook had his putt to win back the Cup. He holed it!

The British were ecstatic but the Prince of Wales was, of course suitably restrained in his comment as he presented the Cup to Taylor:

Naturally I am unbiased in these matters, but I can only say that we over here are delighted to have beaten you over there.

The future magnificent golf commentator, Henry Longhurst, covering his first Ryder Cup, wrote:

There were thousands of people who rushed about the course, herded, not always successfully, by volunteer stewards brandishing long bamboo poles with pennants at the end, which earned them the name ‘Southport Lancers’. Many had come to see the golf, more perhaps to see the Prince of Wales, himself a keen golfer, who had come to give the Cup away.

We saw him in the end presenting it to dear old J.H. Taylor, non-playing captain of the British team, almost beside himself with pride, and we saw Hagen with that impudent smile that captured so many male and female hearts saying, ‘we had the Cup on our table coming over and we had reserved a place for it going back!’ Above all, we saw what was one of the most desperate finishes to any international match played to this day.

Longhurst would write of Easterbrook’s efforts on the last green:

So now Easterbrook was left with his 4-footer, with a nasty left-hand borrow at that, and the complete golfer’s nightmare – ‘This for the entire match’. Even at the age of 24 I remember thinking, ‘Better him than me’. Easterbrook holed it like a man and the Cup was Britain’s.

It was to be a long time before Longhurst or anyone else would be able to write that again.

The Americans are better

Thanks to this win, the British team assembled for the next match, to be played at Ridgewood, New Jersey, on 28 and 29 September 1935, full of optimism. Before they sailed, the team were given a good-luck dinner at the Grosvenor Hotel in Park Lane. All three Whitcombe brothers from Burnham, Somerset – Ernest, Charles and Reg – were in the team but once again Henry Cotton and Aubrey Boomer were deemed ineligible because of their residence in continental Europe.

The new PGA Secretary, Commander R.T.C. Roe, confidently announced:

Though my association with professional golfers in an official capacity is somewhat short, I feel that no team could go to America with a greater opportunity of success than Whitcombe and his boys.

He confidently insured the Cup for the return trip.

Walter Hagen was again captain of the United States team, which like the British team had plenty of experienced players as well as four rookies.

The optimism of the British team was reinforced by the rescheduling of the match from midsummer to September so that they did not have to endure the sweltering heat. However, this optimism was quickly dented on the first day of the match when they lost the foursomes 3–1, two of the matches by very large margins. Nor did things go better in the singles, with the Americans winning the first four and effectively settling the match. Ultimately the score was 9–3, another convincing win for the United States on their home soil.

Back in Britain there was plenty of criticism. Golf Illustrated which, as we have seen, had always supported the Ryder Cup, wrote:

The best team we ever sent played about as badly as it knew how. Scores running into the high eighties tell their own tale, which must be one of summary defeat.

And Tatler wrote: ‘Better not to go at all than be beaten like this every year.’

The American magazine Time wrote, under the headline ‘Ryder Rout’, that the British had been ‘roundly whipped, in a tournament distinguished more by the US team’s off-the-course uniforms than by the quality of anyone’s game’.

‘Win on home soil’