10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

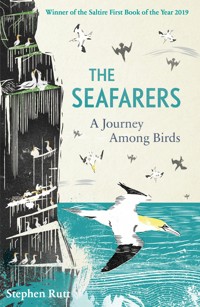

*WINNER* of the Saltire First Book of the Year 2019 / Longlisted for the Highland Book Prize 2019 'A beautifully illuminating portrait of lives lived largely on the wing and at sea" - Julian Hoffman, author of Irreplaceable and The Small Heart of Things The British Isles are remarkable for their extraordinary seabird life: spectacular gatherings of charismatic Arctic terns, elegant fulmars and stoic eiders, to name just a few. Often found in the most remote and dramatic reaches of our shores, these colonies are landscapes shaped not by us but by the birds. In 2015, Stephen Rutt escaped his hectic, anxiety-inducing life in London for the bird observatory on North Ronaldsay, the most northerly of the Orkney Islands. In thrall to these windswept havens and the people and birds that inhabit them, he began a journey to the edges of Britain. From Shetland, to the Farnes of Northumberland, down to the Welsh islands off the Pembrokeshire coast, he explores the part seabirds have played in our history and what they continue to mean to Britain today. The Seafarers is the story of those travels: a love letter, written from the rocks and the edges, for the salt-stained, isolated and ever-changing lives of seabirds. This beguiling book reveals what it feels like to be immersed in a completely wild landscape, examining the allure of the remote in an over-crowded world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 420

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Praise for The Seafarers:

‘The writing lures you in, making you feel that you too might benefit from venturing out in inclement weather, just on the off-chance of seeing something remarkable on the wing to lift your spirits’

– The National

‘An arrestingly vivid turn of phrase . . . An accomplished debut from an exciting new voice in nature writing.’

– The Countryman magazine

‘An evocative book . . . I could taste the salt on my lips and smell the perfume of storm petrels. The Seafarers is a pelagic poem about the birds that exist at the coastal edges of our islands and consciousness. The stories of these hardy birds entwine seamlessly with Stephen Rutt’s personal journey to form a narrative as natural and flowing as the passage of shearwater along the face

of Atlantic rollers’

– Jon Dunn, author of Orchid Summer

‘A beautifully illuminating portrait of lives lived largely on the wing and at sea . . . In this intimate guide to the wild beauty and complexity of seabirds, Stephen Rutt has written a powerful chronicle of resilience and fragility’

– Julian Hoffman, author of Irreplaceable and The Small Heart of Things

Praise for Wintering: A Season With Geese

‘Stephen Rutt urges us to look again at these large, garrulous birds . . . A poignant testament to how we can find peace in the rhythms of the natural world . . . With the arrival of geese comes winter and with their departure we receive a symbolic promise that summer will come again.’

– The Times, Books of the Year 2019

‘A wistful, lovingly essayed volume. Illuminating history and descriptive nature writing make Wintering an understated gem for the festive season.’

– Waterstones.com, Gifts for Nature Lovers

‘Rutt’s dreamy prose is as cool and elegant as the season he charts. His love for them shines throughout a seamless blend of field observations and cultural history, framed by his continuing journey towards discovering solace and sense in nature.’

– Jon Dunn, BBC Wildlife

‘There are undoubtedly health benefits of spending time with wild creatures and I am uplifted by this book and peer upwards searching for a first view of a skein of geese flying overhead to their wintering grounds not far from me. I will never look at geese the same again. Strangely, I can’t wait for winter.’

– Caught by the River

‘From Dumfriesshire’s spectacular skeins of pink-footed geese to the elusive brant, these extraordinary visitors are explored in this beautifully presented book.’

– Belfast Telegraph

For M.C.

Contents

Introduction: London and Orkney

1 Storm Petrels – Shetland

2 Skuas – Shetland

3 Auks – Northumberland

4 Eiders – Northumberland

5 Terns – Northumberland

6 Gulls – Newcastle

7 Manx Shearwaters – Skomer

8 Vagrants – Lundy, Fastnet, Sole and Fitzroy

9 Gannets – Orkney

10 Fulmars – Orkney

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Introduction

London and Orkney

The wind is gale-force and has travelled over nothing but sea since Greenland to greet me here. Early March is not an auspicious time to arrive in the northern isles of Scotland. Standing on the airport tarmac at Kirkwall in Orkney, I feel the coldness of it skimming in along the island coast. I feel the insistence of it. The way it isn’t stopping at my new coat, but cuts through nylon, fleece, jeans, skin, bone. My flight is to be on the smallest plane I have ever seen. One propeller on each toy wing: two seats wide, four seats long. It is half full, which I’d later learn was busy for the time. Evidently rush hour is different up here. Flying is, too: I give my name without being asked, offer to show my printed ticket, some ID – none of it needed. We walk over the runway, duck under the wing and clamber in.

Engine rumbles. Propellers flicker. Seat shakes. Propellers spin, strobing in the corner of each eye. The judder – the wave of sickness that accompanies sudden motion. We begin to taxi. I run out of options to turn around. I can’t go back. I think this might be the most terrifying moment. And then the plane takes off, curving up into the grey above Kirkwall and then it judders and shakes as it hits the wind. I am wrong. I spend the short flight with my fingers crossed, my heart racing, one eye shut and not daring to look, the other wide open, staring at the spindrift racing from the waves. From above, the sea looks dark and frantic, bracketed by tiny green strips of land, the elongated peninsulas and isthmuses of the strangely shaped islands of Orkney. I see white beaches, wide bays, a gannet. Land stretched and warped and frayed. I see the big rocky coast of the island we are landing at. A speck alone, beyond the rest. I see the airstrip, a brown line in a green field, behind a red fence. And I am baffled at why we are coming in sideways.

I see the strata of the rock approaching. I can’t take my eye off the rocks, coming close, closer, then the pilot accelerates – the nose spins and the wheels thump into the grass of North Ronaldsay.

I breathe for what feels like the first time.

Some stories have long roots. The roots of this story stretch back over a decade to a teenage me, standing by a bush, at dusk, with my dad. I had said I wanted to go for a walk and he had taken me to Minsmere, the RSPB’s site of ornithological pilgrimage on the Suffolk coast. We were listening to a Cetti’s warbler, an explosive drumroll of a song, delivered shyly from the deepest undergrowth. This one jumped into a sapling: scrubby and bare, it couldn’t hide the small brown bird. Dad, phlegmatic almost all of the time, dissolved in excitement. It was the first he’d seen in a lifetime of birding. I was swept up in all of it – the deep peace of the reedbed rolling away to the horizon, the mud up the back of my calves, unexpected encounters with small, brown, extraordinary birds. From that moment on, I was guided by birds.

Birds were my awakening to the world outside. Birding teaches you to be aware of subtle distinctions that signify differences. Whether it was the leg colour or a few millimetres’ difference in wing length that enabled me to tell two common warblers apart, or the presence of a wing-bar that revealed it to be extremely rare. Whether I was standing in an overgrazed field, a set-aside field or a meadow rich in life that an owl would soon fly over through the thick light of dusk. Whether the wind in October was coming from the north and my day out would be cold and boring, or whether it was coming from the east and it would be cold and rich in potential. It made me pay attention, not just to these things, but to how and when they change. Whether my first swallow of the year was in March or May – and why. Birding forces you to pay attention to the world as it happens around you and gives you a way of decoding it.

Before I became a birder, I was briefly a fisherman. While sitting behind a rod, fruitlessly waiting, I never thought about global warming, the rise in sea levels, or how the algae in the bay of the lake might be caused by the run-off of unpronounceable agro-chemicals with startling side effects. Fishing taught me futility – that things will probably not go your way. Birding taught me to look at and think about the outside world, to engage with the landscape and all it holds.

There is a gentle art to birding. By which I mean there is no correct way to do it. You can go outside for days or just glance out of a window, notice something, and carry on, your day having become slightly wilder, slightly more interesting than it might otherwise have been. It requires no basic equipment other than your own senses and a desire to notice and to know. Birding makes no demands of you other than these. It is gentle because you can’t force it. It is more productive not to, better to slow down to the speed of the landscape and blend with it. It is an art because there is no set route, no magic key to finding or knowing a bird. To recognise one requires a myriad of moment-specific considerations. And much of it can be done by intuition – the application of experience – rather than rules. You never stop learning. It can open you up to things either extraordinarily beautiful or extraordinarily depressing.

Being a teenager enabled me to be obsessed without shame. I absorbed the Collins field guide to the birds of Europe. Then Sibley’s field guide to American birds. Then the monographs to specific families of birds, then specific species. I absorbed site guides, built a mental map of the world’s birds, read blogs, dissected forums. I found a network of others from across Europe and we spent evenings indoors, online, talking about mornings outdoors. We were captivated by the Scottish islands. I had never been but, from the photos I had seen and the books I had read, I constructed my own mythic version of them: quiet, solitary utopias, places where one could not ignore nature, and if one tried then nature would come and find you. Come and rattle at the windowpanes, or land in your garden, or squat on your car bonnet, until you were forced to pay attention again. A place for the inveterately shy.

It is a fifteen-minute flight from the town of Kirkwall, Orkney, to the outer island of North Ronaldsay. I’d come from London, to an island whose population would fit on the top deck of a double-decker bus. It was a sort of decompression therapy – coupled with an urge to satisfy a consuming passion.

I was obsessed with migrant birds. In love with their freedom, their unconstrained border-crossing ability, their bravery at heading out across sea, powered only by small wings. It seemed to me that birds had the power to express untouchable freedoms. If the world we live in can feel entangling, entrapping; birds can transcend that.

I was here to volunteer at the bird observatory, one of the best places to witness migratory birds in Britain. It is no coincidence that the other places that can make that claim – Fair Isle, Portland, Spurn Point, the entirety of the Norfolk coast – are all on the edges of the British Isles. The edges are the first or last land that a small migrating bird finds on its migration over the sea. Last snack or first sleep. These edges are a place for strong winds and tired wings. When the wind is coming from the Continent in migration season, it eases them our way. Bad weather makes them seek shelter in the unlikeliest of places, and on a good day – for which, read, day of hellish wind and rain – there can be a surreal number of birds in odd places. I saw goldcrests in the drystone walls and ditches, woodcocks behind sheds, wrynecks sheltering in the ruined roofs of dilapidated crofts. It’s known as a ‘fall’, for when you are experiencing one, it feels as if birds are falling out of the sky, their onward migration accidentally halted by the need to seek out any sort of solid ground.

Falls are few and far between. On an island roughly 3 miles long and a mile wide, you learn to find pleasure in what you have, not what you want.

When I walked out the morning after I landed, the wind hadn’t abated. I crossed two waterlogged fields to the west coast. The sky was dark with impending rain, the coastal rocks white under spume, spindrift blowing about the air like snowflakes in a gale. The air was thick with salt, glazing the landscape. To this day I don’t know how I didn’t break an ankle there and then on those hidden rocks, white to the eye and slippery as oil. It was an enforced slowdown – all became deliberate, measured, a two-footed crawl. Shedding city speed, one step at a time, while gulls played in the gale around me, starkly white against the sky, light in the heavy weather, free.

I made it to the ramshackle hide by a collapsed drystone wall just as the rain began. It overlooked a loch, instantly churned up by the deluge, while the ducks fled for the meagre shelter of a small muddy bank. The gulls cleared off. The drumming on the roof sounded like applause. And when it stopped, the wind dropped, the clouds dissipated and the sky turned Mediterranean blue. My phone buzzed. A text from Mark, one of the wardens: ‘Welcome to Orkney.’

I squelched over the fields back to the main road, and followed it up the high ground to the top of the only hill on the island (although at 20 metres high, ‘hill’ is perhaps an exaggeration). I could see scattered crofts, some with a waft of smoke from the chimney, others dilapidated and crumbling. I could see the delicate threadwork of the drystone walls, two sandy beaches and a lighthouse. Fair Isle to the north, Westray to the west, Sanday to the south. True horizons again.

London is no city for an introvert. Or this introvert at least. It should have been the time of my life. I was twenty-one. I had just graduated with a good degree and fallen into a job immediately. I had moved to the capital and lived with friends. We were young and we were free and we had a taste for good booze and bad food. I felt as if I had achieved. I had no idea what was supposed to come next.

I visit it regularly in my mind, trying to walk my memories back to where the rot set in. The front gate in the thin privet hedge, from which every morning a spider would weave its web at face height and catch my housemates unaware. The rosebuds sealed shut, waiting to burst open in the spring sunshine. The curtains still pulled tight. It is a picture of post-war suburban surface bliss. It could be anywhere in the red-brick sprawl of London along the fast roads to the west. Along the street, ambulances hurtle, lights flashing. Busses squeal, cars rev, a Boeing roars along the Heathrow flight path, a sound that reverberates down the road. No birds sing.

From the outside looking in, there appears to be nothing wrong – if you like that kind of place. Slightly staid maybe, possibly slightly stifling, but no warning signs. This was the landscape I lived in – horizons shrunk to the limits of the street. The sodium-orangestained night sky, which I watched from my bedroom window, waiting for a single star to appear, or for a fox to slink between the parked cars. I would walk around the local park and see more joggers than animals. Here I once startled a snipe one windy morning walk before work and remember vividly the weirdness of it – a bird of the wilder wetlands, flying off towards a horizon of the London Eye and the Shard. It was a small token. Insufficient fuel to maintain the connection to nature, to the world outside.

I had built a mental dependency around space and quietness, the two things that nature gave me that I required to find my peace. Behind the meagre privacy of that privet hedge, starved of nature, I was short-circuiting. Things began making no sense in slow, slow motion.

I was on the London underground. Central line. Saturday evening. Due to meet up with a friend. Unusually, I had a seat, not that that would help. As the journey progressed from the west to the centre of the city, the carriage filled up. Standing room only became no room only, became people squashing on, regardless. Crowds affect my breathing. Crowds make my chest tighten. And the Underground is an airless place anyway, without the crowds; with my breath catching in the back of my throat, my body tensing, sweat spreading from my temples, down my shoulder blades, my vision blurring, the distance over the shoulders of the people was becoming warped, elastic, lightness flooding into my head. I barged out at the next stop, stumbling onto the platform, gripped with fear. Inexplicable fear. I slunk my way, from side street to side street to the rendezvous, very late, dumb with angst.

I knew this to be irrational. Because I had got the Underground before, because I knew there would be coping mechanisms. But I felt like a taxidermy specimen, pinned and mounted, except I was not dead, and the dull weight of anxiety pinning me alive felt impossible to escape from.

I stopped going outside. I stopped answering my phone. I resented speaking, resented breathing fumes and dust instead of air – a fuel rekindling the asthma in my lungs. I took holidays from work to spend lying in bed or on the sofa feeling nerves trembling down my arms, nerves where they hadn’t existed before.

Life became policed by the anxieties in my head. The claustrophobia, the primal fear of other people. Anxiety strung me out, made me feel as if I might never again be the person I was. My landscapes, physical and mental, had shrunk from the East Anglia of my childhood, to west London, to the street, to the house, to the days I couldn’t leave my room.

Shyness took over. Shyness has always been a part of me, but in the exhaustion, the feeling of permanent defeat, it colonised me like a virus. All-consuming. It silenced me and made me feel burning shame whenever several sets of eyes turned to me and expected an opinion. Silence is a radical approach to a city, to a culture that never shuts up. It was also, for me, futile.

I lasted eighteen months. The bravest thing I did when I was twenty-two was leave. Being young, single and coming to the end of a tenancy agreement is a freedom either glorious or terrifying, but it was a freedom I was unusually determined to make the most of. It was how I ended up on that plane.

Flicking through my diaries from that first month on the island, I note a preponderance of words that I would never use now. Elysium, Valhalla, Nirvana: I had found my paradise beyond earthly realms, although it was really just the earth that I had fallen back in love with. These days were a privilege – building stiles, painting the observatory, rewiring the funnel traps1 for catching birds, tending to the sheep and exploring. I saw a 98 per cent solar eclipse, the Northern Lights, meteors and a lost goshawk flying around in its own raincloud of redshanks. Shorn of the daily stresses of my London life, the daily unpleasantness that people put up with just because it’s London, I was attaching significance to everything. The sunset, the stars, the way the wind always whistles over the walls impertinently. The way the sea can be heard from everywhere, unless muffled by a haar or, on the rarest of days, when no wind correlates with no swell and turns the sea into a rippling, velvet-like surface, shining and stilled, and the waves gently kiss the sand. These days become as precious commodities – to be shared but never exchanged.

I have tried to read Thoreau several times and always failed. But I suppose this was my own version of Walden, and deliberate living. We were both surrounded by the wild: him only a mile from town, me connecting to people on Twitter and watching Match of the Day in the evenings. I don’t think this makes the experience less valid. Life is life, anxiety is anxiety – deal with it how you will. Questions of how to live seem the most essential to me. For seven months I chose to live with nature at the foreground of my daily life – noticing the birds, the first flowerings of the marsh orchids, the darkness of the night sky and the lightness of it in midsummer.

I don’t think that nature exists as a cure; not properly anyway, not as a replacement for 2,000 years of medical achievement or changing your lifestyle or whatever you do that works for you. I remembered then, away from London, that down the street I lived on, the roots of the plane trees that flanked the road kicked up the paving slabs. And across from my office, the thin summer smoke of buddleia that colonised the top of an old factory chimney and would wave gently in the breeze. I remembered the thunderstorms I used to stop and watch as they cracked open and cleaned out the night sky, and the way that, when I was inside and wouldn’t dare to leave the house, spiders would catch my attention, space-walking across the window frame, kicking threads out with their hind legs and weaving them into webs. Somehow I had lost sight of these small comforts. Perhaps they were never enough.

I was still shy on North Ronaldsay. But it no longer felt discordant, as it did in the city. Place and personality rhymed, in a way that nowhere else had, that nowhere else has. Orkney felt like home.

Although the peace felt as if it would last forever, it didn’t. The season got busy. I got exhausted. The novelty of weather wore off and it rained all May – and all June – and the grass didn’t grow, my wellies wore through and I spent the season with wet socks, waiting for a fall that never arrived. While I waited, I flicked back to pages in the field guide I hadn’t looked at for years. London had isolated me from seabirds. There was no prospect of seeing them and they had faded from my mind, other than as memories from holidays to islands and far coastlines. Orkney rekindled an old love.

It was the first tern out of the grey in mid-May. It was the first storm petrel fluttering like a butterfly between the crashing waves, somehow never quite being washed away. The Manx shearwater of spring and the sooty shearwater of autumn, sweeping the Atlantic on stiff wings, in what looks like one perpetual glide. While I once gazed at their pages in guide books on the other side of the country, I was now living among them. Their cold, wet peripheral exoticism was mine too. I lost my heart to the fulmars, the kittiwakes and the black guillemots. I lost my heart to the seabirds.

To understand the appeal of a seabird, it’s necessary to explore what a seabird is, and what it isn’t. Most birds migrate, most will cross a sea. They are not seabirds, not any more than a seabird becomes a landbird when it sets up residence on a cliff to breed every summer.

A scientist’s definition might focus on how they have feathers covering their auditory canal, to prevent water entering their ears when they dive for food, or to prevent flying with muffled hearing, or – more likely – to minimise the effects of pressure. Another scientist’s definition might focus on the Procellariiformes: the order that contains the petrel, shearwater and albatross families. They have a tubenose: a prominent bulging nostril above the bill, an adaptation specific to these families, allowing them to smell food on a sea breeze and expel the salt from their exposure to saltwater. But this would be partial definition. It would not include the auks, gannets, gulls, skuas, terns and eiders – all of which are predominantly found, or should be found, on the edge. Some might focus on their power of smell, unusually highly developed in some seabirds, while most other birds cannot smell particularly well. The problem is that all definitions of a seabird are partial. Most would exclude the eider. They might live on the coast, but they feed at sea. It is the sea that defines them and their capacity for coping with it makes them difficult, makes them wild, makes them captivating. The ‘should be found’ is important here – though some birds always end up lost, things are changing on this front. Some are moving inland.

Seabirds live predominantly out to sea – feed at sea, sleep at sea, and experience a habitat that is simultaneously as vast as the ocean and as small as the gap between two waves. Seabirds are mysterious. Away from islands, they are usually seen from land only when summer storms push across the Atlantic and sweep them towards the ocean’s edges. Seabirds love islands, as I love islands: the further out of the way they are, the less disturbance there is, the more perfect they are. All use them to breed – an act of convenience – though the vast majority occupy tiny cliff ledges, several hundred metres above the sea. It’s technically land, but I wouldn’t want to stand there.

Seabirds are transient, fleeting, remote things – yet they are also moving into towns and cities. When they are written about, they reveal a good deal about the author. As with all animals, they are good subjects on which to project human desire. Seabirds are some of our most loved and hated species. They inspire religious devotion or revolutionary zeal. Hermitic living or the hectic crowd. They are symbols of revolution, pirates and victims. They are bounteous and declining – and, like almost everything symbolic of the remote and wild, they are deeply touched by human activity: pollution, overfishing, the warming of the seas.

It is 5 a.m. Dawn breaking over the lighthouse. The mucky feeling of being awake and the mind unwilling despite the acrid, too-strong coffee coursing through my body. Rosy dawn, purple clouds, golden light; the sea stilled to a pale-blue mirror. Black guillemots – known by their lovely old island name, ‘tystie’ – breed here in their hundreds. North Ronaldsay lacks the spectacular cliffs and ledges that most seabirds need to breed. Instead it has a coastline of slippery, sea-slicked rocks and beaches of boulders – ankle-grabbing, unforgiving for the two-legged. Under this geography, lies another – a subterranean labyrinth of nooks and crannies between the rocks. As strange as it may seem, these gaps under rocks are an ideal location for tysties to nest. It complicates keeping track of them, makes the annual census of their breeding population tricky. The best opportunity arises in mid-April, a rare but apparently regular window of calm before the spring storms. In the early morning, the guillemots come out of these gaps – standing proud on the edges of the rocks or surfing the lapping waves. The gentleness of the sea gives them nowhere to hide, enabling the observatory staff to count them. The lack of wind, eerie, making me feel as though I were somewhere else, somewhere other. We all take quarters of the island coast – I count 200 in two hours of walking the rocks. The island’s total: 653.

And then, as spring begins in earnest, the guillemots all seem to disappear from the edges. Then guano splashed in the gaps in the rocks, like daubed white paint. Single tysties flying from the sea into the crevices, carrying bouquets of butterfish.

A few weeks later we made our moves, working in pairs, scrambling across the rocks. We’d find these gaps, put our shoulders to the boulders and fish with our hands – stone, shit, stone, fluff. We’d close our hands around the fluff, gently but firmly, and pull them out. The first humans these tystie chicks will have ever seen. They greet us in the same way every time: a nip to the wrist with one end, a dramatic defensive shit from the other, a hosepipe spray of white. The ringing process is quick, to minimise stress. The attaching of a metal ring with a unique code allows us to track the productivity, longevity and dispersal of these birds. We return them to their gaps in the rocks.

We don’t have long with each bird – cautious speed, not rushing, but not delaying. By the time we’ve completed the scramble across one small patch of coastline, the exhaustion is complete. The ache in our arms, the raw beak-pecked flesh at our wrists, our jeans whitened.

The chicks are all in varying stages of development – a symptom of the wet, windy spring, where the usual progression of things was fractured. Some are adult-sized, almost fully feathered, and ready to escape within days. Others are the size of a large pebble, black and fluffy like tumble-dryer lint, with a beak, shiny eyes and full-grown legs.

It was, in spite of the spring, the best year yet for tysties. We found 100 nests and ringed 138 young – more than twice the number of nests and young that there were in 2013. I was not the only one bouncing back. I was not the only one surviving with the weather.

Trapped in the brick sprawl, the labyrinth of suburban streets, I could never imagine becoming so involved with the life of a species as I became with those tysties. A love rooted in empathy begins with getting on hands and knees, prostrate on the rocks, covered in filth. Not quite midwife, not quite impartial observer. Several extended months of low-level anxiety every stormy day, several months of stumbling over rocks, counting beyond my capabilities, and beak-nipped flesh. Several months of hoping on fish swimming unseen in the black Atlantic or azure island bays. It teaches you a species of faith in the resilience of things: in the sea, in small birds, in yourself. At the end of the season, as they decamp from the gaps in the rocks to the sea, they vanish. Numbers dwindle to barely a handful. I wasn’t going to be there in winter to see them return, as mostly white, flecked with black feathers – the inverse of their summer plumage. I had faith that they would.

I left Orkney, mostly whole, mostly human again, but with a seabird-shaped hole in my heart. So I travelled again. From Shetland, to the Farnes of Northumberland, down to the Welsh islands off the Pembrokeshire coast, before coming back up to Orkney. I travelled deliberately, to explore the mysteries, paradoxes and histories of this family of birds, the places they reluctantly inhabit and the people who follow them too.

This then is the story of those travels – my love letter, written from the rocks and the edges, for the salt-stained, isolated, and ever-changing lives of seabirds.

1

Storm Petrels – Shetland

There are many shades of darkness. The first is the obsidian sea, glittering towards the last vestige of light on the horizon. Close by, it is absolute black. The sea’s motion cannot be seen or felt, only heard in the slap of water on the bows of the boat. The second shade is the sky, solidly overcast, predicting tomorrow’s storm. A slighter darkness, the last of the light held in the clouds. There is just enough light to see by without a torch as we disembark onto the jetty at Mousa. It is 10.30 p.m. In an hour it will be dark enough.

To darkness, add silence. Silence and mystery.

We walk along a grass path, in parts worn down to the underlying stone, and cross over the 60-degree-north parallel, marked by a driftwood bench. We pause at a drystone wall that runs across the island, seeing little and hearing nothing. We carry on around a bend and a shape begins to emerge from the dark ground ahead of us.

It is Mousa Broch.

It was built 2,000 years ago, as part of the chain of brochs unique to Iron Age Scotland, found mostly in the highlands and islands. Mousa’s is one of the finest remaining examples. It is 13 metres high and shaped like the cooling tower of a power station: circular, wider at the base and gently concaving up to the open top. Built of island stone, it is the same colour as the walls and the stony beaches. In the slowly gathering gloom it looks organic, grown out of the bones of the island. We are unsure why brochs were built and what they might have been used for. The darkness of time: occluded intentions, obscured uses.

We continue towards it. Past a beach of loose rocks. Our ears grasp for sound, but the beach is silent, the stones still holding their nocturnal secrets. And it is thanks to the dry stones of the island – beach, broch and wall – that we are here. Twelve strangers, all compelled to take a late-night boat ride from one of Britain’s most remote islands to one of its even smaller neighbours. Drystone structures, without mortar or pooling water, create spaces out of the reach of predators and bad weather. Spaces get colonised. They become shelters for seabirds.

There is a small stone entrance to the broch. We crouch, then shuffle through a 5-metre-long passageway. There is a large step up. We emerge into a circular chamber – a new darkness of stone surroundings, the darkness of a building with no clear purpose. Around this inner chamber and towering above us run two concentric walls – one inner, one outer – their strength drawn from the weight of stones pressing against each other for two millennia. Between these two stone walls – in the darkest of darknesses – rises a staircase. I switch on my head torch, weakly illuminating the steps that curve with the walls as they climb the 13 metres to the top. There is room for only the front half of my boot on each step. I can feel how time has hollowed out the centre of each well-trodden stone. My hands grasp the rocks of each wall for support.

If I can’t see birds, then I listen for birds. Here in the silence of the staircase I can rely on another of my senses. I can smell them. The air is thick with the musty scent of storm petrels, the damp, stale smell of old books or older churches. It is similar to the smell of laundry that hasn’t dried, a clinging, reluctant dampness, as if the birds themselves can never get dry. It is incongruous, a safely familiar scent, something conservative. It is appropriate that they should smell like an old church, little aired or used: the boatman suggests the origin of the word ‘petrel’ is found in St Peter, walking on water, given the way the bird’s legs dangle over the surface of the sea as it forages between the waves. They were also once imagined to be the souls of drowned sailors and cruel sea captains, trapped in birds that were thought to fly forever.1

The truth is more prosaic. Most birds have a poor sense of smell and wouldn’t be able to smell a storm petrel. But seabirds are unusual for having and relying on a well-developed sense of smell. In the darkness of the colony at night, in the similarity of the maze of stone gaps, storm petrels can smell each other. And they can smell family. Researchers have discovered that, in the breeding season, storm petrels are more likely to avoid areas marked with the scent of their relatives.2

At the top of the staircase a heavy gate of wood and chicken wire seals the space between the walls. I open it with a shove. I step out at the top, the odour of petrels dissipating in a flood of fresh air. I step out at the top onto a narrow ring of stones suspended between the metre-thick walls, a 13-metre fall plunging away each side of me over a low wall, outwards down to the grass and stone surrounding the broch, or inwards down to the inky darkness of the central chamber. From the top, the view of headlands disappearing in the darkness, the hills of Mainland Shetland merging into clouds, the sea as dark as the sky. It takes a moment for place and time to sink in. I stretch my hands out between the walls. Lichens, stiff and wiry after a dry spring, scratch at my fingertips.

Then they begin to sing, from the gaps between the stones, a sound that seems to emerge from below the lichens. The first faintly. Then others. Each storm petrel joining increases the confidence, adding to a quiet choir of birds. Each churrs – hiccups – churrs. It is described by birders as ‘like a fairy being sick’, a cliché so frequently used as to have its origins lost in a blur of repetition. It is a description that captures the otherworldliness of their song. It is a rhythmical purring, but with the pitch of a Geiger counter, or the tuning of an FM radio through static, or a struggling food blender. The hiccup is a squeak, with a pause, the noise of a cork being twisted in the neck of a glass bottle. To describe it in these ways is to anchor something essentially indescribable in the mundanity of everyday life. But it is essentially unlike these things: it is the sound of the magic of islands.

Darkness creeps; light leaching from the clouds. Storm petrels returning from the sea appear at the edge of vision, firstly as a flicker, an apparition in the dark. Then they jink in on erratic wings, beats too fast to follow, always disappearing. They seem bat-like on the approach to the broch. Their defence in the dark against predators is the utmost agility and unpredictability. There is the darkness of their plumage too. Each erratic wing – only 20 centimetres long – is the colour of the night. A matte but not total black, shaded brown where the stark sun at sea bleaches the feathers. On the underside, a white line where the flight feathers meet the flesh and bone of wing. Then, bizarrely, a white rump that flashes like a beacon in the dark – an advert to predators for which science has no explanation.

At the broch they aim for the walls. Land on the stones, scurry for their gaps, rumps catching the vestigial light. Their feet are tiny, webbed, clawed, and as they scurry they scratch at the desiccated lichens, like mice. Bat-like; mouse-like. Storm petrels are hard to pin down, elusive in the dark; like and unlike other animals. The incubating bird, singing from the broch wall, slips away, out into the darkness of the sea at night.

There are places where time unspools like an old cassette tape reel and cannot be wound back up. There are places where perspective warps and the present and the past are mere touching distance apart. Standing on top of Mousa Broch, senses stimulated by the sight, sound and smell of storm petrels, I look out to the dark mass of Mainland Shetland, where earlier I could see the low, round remains of Burraland Broch. I can see the lighthouse at Sumburgh, blinking rhythmically, where there was once a fort, where once the first fires would have been lit, a message spread from broch to broch giving advance warning of invaders from the south. So one theory goes. But there are other theories too. The mystery doesn’t matter, not to me, here, now. In the vanishing light, watching black birds in the night sky and white lights blinking on the horizon, standing where people must have stood, 2,000 years ago, hearing, seeing, feeling the same things.

There are few better places to see storm petrels than Mousa. The island is home to the most easily accessible and perhaps the most famous colony of the birds anywhere in the world. The other colonies are obscure: smaller islands, fewer boats. The birds require the gaps in the rocks but, more pressingly, an absence of rats, cats, stoats or any other land-based mammal that can fish with a clawed paw between the rocks to reach them or their eggs.

This species of storm petrel used to be known, myopically, as British storm petrel. But it is not just British stones they like to nest in; it is not just British-born birds that fly through here. Ringing, the most primitive way of tracking bird movements, has revealed that passing our coastlines at night are storm petrels bred in Portugal and Norway, among other places, on their way to or from waters off South Africa. They are now known as European storm petrel in recognition of the fact that their breeding range extends out beyond our north and western coastline (and that of Ireland) to Norway, Iceland, the Faroes, France, Sardinia, Sicily, the Canaries – even Spain, where they breed on Benidorm Island, fluttering and churring in the darkness just offshore, while the British on holiday party on the dazzlingly lit seafront and in the neon-lit bars, unaware of what shares the night with them.

If you gaze at the broch too long, you begin to feel connections stirring to the deep past, to the Iron Age inhabitants, the master builders and the unbroken line of occupation until the last family left in 1853. Stare deeper at the birds and you go all the way back, back to the deepest past. The marigold-mouthed shag on the rocks hanging its serpentine wings out is beautiful and primitive. It is the connection to the dinosaurs that lurks just beneath the surface of our birds. Mousa is connected to all of this and none of this. Like the storm petrels that slip past in the night, barely there, islands entangle us in a tantalising web of potential connections: flight paths, presences, histories and geographies. All transient.

There is nothing new. There is nowhere new. There is nothing unseen in the large island and small archipelagos that make up Britain. I am following in the footsteps of other watchers, walkers, writers: walking similar islands, watching the same species that they first conjured relationships with, committing my experiences to paper with a like-minded fervour.

I start with the storm petrels as a nod to my forebears. Off the coast of Pembrokeshire, Wales, there lies a small island – an island dreamt about since the time of the Vikings, who saw it from their longboats in its original, mint-green, vegetated condition. They called it Skokholm, meaning ‘wooded island’ and sailed on. All that remains of that vegetation today are the flowers that survived the Norman farmers, the makers of the island who brought the now ubiquitous rabbits and cleared the land. There is also a farmhouse and a flag of white fabric hoisted high on a driftwood flagpole. On it flutter the images of three storm petrels.

Anyone trying to make a home of an island like Skokholm has to endure the winter. Winter comes with an almost absolute isolation among the crashing waves. It puts a halt to most attempts at staying. To survive these conditions requires more than creating a home. To thrive in these conditions you need to dream.

Ronald Lockley and his first wife, Doris, were the dreamers of this place – the storm petrel flag a result of Doris’s handiwork. Ronald Matthias Lockley – or R. M. Lockley as he became known to the world at large – authored fifty-eight books and was a prolific writer of articles, some hugely popular and influential in their day and some still so. Most of his work is inspiring, innovative and the basis for much of what we know – and how we know it – about certain species of bird. His star has sadly been overtaken by figures more grandiose – figures with bigger, better flags.

Lockley was born in Cardiff on 8 November 1903. When he was five, his happy childhood was interrupted by a sudden brush with his own mortality. A freak accident in which an out-of-control horse crushed him against an embankment, leaving him bedbound for a month. In The Way to an Island (1941) Lockley remembers reading The Swiss Family Robinson during his convalescence. This might be when the desire for an island of his own first lodged in his imagination. It is followed by Robinson Crusoe, The Coral Island by R. M. Ballantyne, and then works of natural history, including Charles Waterton’s Wanderings in South America – a book that inspired Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace as young readers on their way to scientific fame. Lockley’s young mind begins to wander through the vastness of imagined space.

The young Lockley was unfamiliar with vast space. He grew up in Whitchurch, at the time a suburb of Cardiff, surrounded by farms and stables that would be subsumed by the city in the 1960s. His universe is the garden and a gap in the wall that leads to the farmer’s fields, which would be his surreptitious stomping ground. Lockley feels the lure of the land. The farmer keeps remaking and repairing the drystone wall. The hole keeps reappearing.

When he appeared on Desert Island Discs at the age of seventy-six, Lockley was asked how he first became interested in birds. In his answer he pinpoints another period of childhood convalescence, this time sitting still for three months in a chair in the orchard, noticing and keeping a diary of birds and wildflowers.3 In The Way to an Island he recounts how, as a child, he was not allowed to leave the dinner table until he had cleared his plate. He devised a paper-bag-in-pocket system, in which he would stash unwanted food to give to the grateful birds just beyond the hedge. He writes that ‘out of this sly practice came the good of intelligent bird-watching’.4

Lockley claims with youthful zeal that by the age of ten he ‘knew every common bird intimately’.5 (This is something I would struggle to say even now, after a decade of obsession and with all the benefits of modern equipment and information. I have the Collins Bird Guide, a distillation of all Europe’s birdlife, with bright images depicting birds drawn from life, and dense text summarising all the potentially useful information. It fits onto an app on my iPhone.) Lockley thought Howard Saunders’ breezeblock of a book, The Manual of British Birds, was ‘indispensable’.6 The 1927 edition runs to 834 pages. In a knapsack there wouldn’t be much space for anything else.

Saunders’ book was first published in 1899 and its images are based on taxidermy specimens imaginatively brought back to life by a range of artists, most of whom had not set eyes on the living bird. Most are as stiff as bad waxworks, the subtleties of the warblers lost in the monochrome engravings. The seabirds that Lockley grew up to love are all standing on rocks, not flying as they are almost always seen, and it’s like trying to understand an opera from the captions, or a film from the script. Sometimes this disconnect produces impossible images. The artist has the legs of the Manx shearwater far enough back to be anatomically correct, but somehow holding the front of the body up – a stance the birds are physically incapable of holding. They don’t walk, they shuffle.

If there is a gap between the images of dead birds and the real living bird, then the text goes some way to closing it, offering alternative names and detailed information on distribution. The description of plumage leaves a lot to the imagination, an indication that identifying living wild birds was still a relatively unusual activity.

Lockley was born at an auspicious time for the study of natural history. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds had been formed in 1889 by Emily Williamson as part of the first stirrings of concern about conservation in the public imagination. It was a movement with which Lockley was instinctively in tune. In his early teenage years he used to go egg collecting. He watches a spotted flycatcher nesting in the garden and gets drawn into the way the parents come and go, and defend their young from a cat. He names them. A real-life prototype Springwatch. It is the first instance of his style of studying: of patient observation, matched with an enquiring, curious mind and a respect for the lives of birds. It is the first hint that his boyish enthusiasm would form the career that would go on to shape the entire field of birdwatching. His time with the spotted flycatcher nest is the moment Lockley gives up egg collecting. It is the summer of 1919, the fifteen-year-old’s self-imposed ban coming thirty-five years before egg collecting is officially made illegal.

At around the same time Lockley builds a hut for himself in the woods between two streams and gives it the name ‘Moorhen Island’. It’s a place where he can store books, write poems and bunk off his education in favour of just being in the woods, being solitary and being with his burgeoning interest in nature that nobody shares. In his recollections it is Eden-like.

Lockley’s early life was characterised by islands – fictional and metaphorical. Islands of the mind, islands of obsession, islands of himself. By the age of five he had decided that he would probably spend the rest of his life alone. Looking back in 1969 in The Island, he identifies his ‘most burning desire’ to ‘dwell alone and simply upon a small island of my own, to study its wildlife intimately’.7

Then there comes a day trip to his first real island: Lundy in the Bristol Channel, 12 miles off the coast of north Devon. He identifies the auks – guillemots and razorbills – and kittiwakes on the cliffs. It is not until the boat back that he finally meets the species he would later become synonymous with, the Manx shearwater, mustering in the sea. Somehow he manages to identify them from the engraving in The Manual of British Birds. It is more than likely that shear-waters bred on Lundy then, though Lockley seems unaware of this. He suggests they’re heading to Pembrokeshire, to Skokholm and Skomer. His curiosity was caught. It was inevitable that he would follow them there.

Lockley was twenty-four when he arrived at Skokholm. I was just about to turn twenty-three when I washed up in North Ronaldsay. I follow an echo of him throughout my journey.