Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jentas Ehf

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

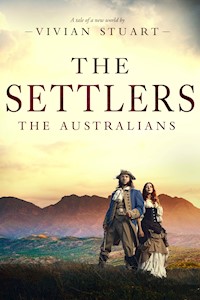

- Serie: The Australians

- Sprache: Englisch

A RAW LAND DRENCHED IN BLOOD, PASSION, AND DREAMS... The third book in the dramatic and intriguing story about the colonisation of Australia: a country built on blood, passion, and dreams. England sends convicts to Australia, but among them, there are hard-working men and women who wish to create a new life for themselves. The same desire is shared by those who are free — but it will be a gruelling fight for survival. And the strong, young, and stubborn Jenny Taggart does not give up ... Rebels and outcasts, they fled halfway across the earth to settle the harsh Australian wastelands. Decades later — ennobled by love and strengthened by tragedy — they had transformed a wilderness into a fertile land. And themselves into The Australians.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

The Settlers

The Australians 3 – The Settlers

© Vivian Stuart, 1980

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2021

Series: The Australians

Title: The Settlers

Title number: 3

ISBN: 978-9979-64-228-2

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

The Australians

The ExilesThe PrisonersThe SettlersThe NewcomersThe TraitorsThe RebelsThe ExplorersThe TravellersThe AdventurersThe WarriorsThe ColonistsThe PioneersThe Gold SeekersThe OpportunistsThe PatriotsThe PartisansThe Empire BuildersThe Road BuildersThe SeafarersThe MarinersThe NationalistsThe LoyalistsThe ImperialistsThe Expansionists–––

For Kim and Lee, William, Simon, Edward and Marjorie ... my most affectionately regarded Australian family.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges, most gratefully, the guidance received from Lyle Kenyon Engel in the writing of this book, as well as the help and cooperation of the editorial staff at Book Creations, Incorporated, of Canaan, New York: Marla Ray Engel, Philip Rich, and particularly Rebecca Rubin, who travelled a long way in order to work on it.

Also deeply appreciated has been the aid in the field of background research so efficiently given by Vera Koenigswarter and May Scullion in Sydney, Australia.

The main books consulted were: The English Colony in New South Wales—Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins, reprinted by Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd., 1910; The Macarthurs of Camden—S. M. Onslow, reprinted by Rigby Ltd., 1973 (1914 edition); A Colonial Autocracy—M. Phillips, P. S. King & Son, 1909; A Picturesque Atlas of Australia—Hon. Andrew Garran, Melbourne, 1886 (two volumes, kindly lent by Anthony Morris): The First Twenty Years of Australia—A. Bonwick, 1882; Rum Rebellion—H. V. Evatt, Angus & Robertson Pty. Ltd., 1938 (reprinted 1975); A Book of the Bounty—G. Mackaness, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1938; Mutiny of the Bounty—Sir John Barrow, Oxford University Press, 1831 (reprinted 1914); My Love Must Wait—Ernestine Hill, Angus & Robertson Pty. Ltd., 1941.

These titles were obtained from Conrad Bailey of Sandringham, Victoria, and through the York City Public Library and the recently retired City Librarian, O. S. Tomlinson. Maps were made from copies obtained from various sources, including the Mitchell Library, Sydney.

Because this is written as a novel, a number of fictional characters have been created and superimposed on the narrative, but the basic story of Australia’s early years is factually and historically accurate. When real life characters’ actions, adventures, and misadventures are described, they are true and actually took place as nearly as possible as described, having regard for the novelist’s obligation to tell a dramatic story against a factual background. In the light of hindsight, opinions differ as to the merits or otherwise of Captain John Macarthur and also of Governor Bligh—each has his admirers and his critics, just as each, being human, has his vices and his virtues. Both are shown here, warts and all ... but it is a fact, which the author freely acknowledges, that John Macarthur played a very prominent and valuable part in rendering the colony prosperous by establishing its wool industry. He also, as Book Three in this series will illustrate, came perilously near to destroying it ...

The author spent eight years in Australia and travelled throughout the country, from Sydney to Perth, across the Nullarbor Plain, and to Broome, Wyndham, and Derby, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide, with a spell on the Dutch East Indian Islands and on a station at Toowoomba, having served in the Australian Forces and the British XIV Army during World War II.

Prologue

Captain Edward Edwards, commanding His Majesty’s twenty-four-gun frigate Pandora, completed the entry in his journal, and as he waited for the ink to dry he read it through once again, a frown drawing his beetling red brows together in an ill-humoured pucker.

Under the date—Saturday, August 28, 1791—he had written:

Passed numerous islands and cays. Coast of New Holland sandy and barren. At noon, in latitude 11°18’S, longitude 144°20’E, sighted what I conceived to be Cape York. A boat was sent to search for the opening in the coral reef, marked on Mr. Cook’s chart as leading through Endeavour Strait and into the Gulf of Carpentaria.

This being discovered and soundings taken, I altered course, intending to come to anchor off the entrance to the strait during the hours of darkness, passing through it to double the north part of New Holland at first light.

The reef—designated the Labyrinth or Great Barrier Reef by Mr. Cook—runs along the greater part of the eastern coast, and being extensive and much of it uncharted, it presents a grave hazard to navigation. Mr. Bligh gave the corrected position of Cape York as 141 ° 15’E but I consider his reckoning—made in an open boat—to be 3°05’ wrong.

Captain Edwards’s frown deepened. William Bligh’s epic voyage, in a twenty-three-foot launch from Tofua in the Friendly Isles to Timor in the Dutch East Indies, with survivors of the Bounty mutiny, had made him a popular hero in England. Any criticism of Bligh might therefore be misunderstood when Edwards’s journal was presented to Their Lordships of the Admiralty for perusal. He sighed and, reaching for his quill, stroked out the last three lines, wondering yet again what lapse of vigilance or discipline on Bligh’s part had permitted his first lieutenant, Fletcher Christian, to lead more than half his ship’s company to rise in mutiny against him and deprive him of his command.

Reassured by the sounds reaching him from the deck above that all was well, the Pandora’s captain started to riffle through the earlier pages of his meticulously kept journal. The Bounty mutiny had taken place on April 28, 1789: Bligh had reached Timor on June 14 with eighteen loyal members of his crew, and had returned to England on March 14 of the following year. His account of the piratical seizure of his ship and the consequent sufferings he had endured had roused not only the Board of Admiralty but the whole country to anger—which was the reason, Edwards reflected wryly, that he was here.

Cleared by a formal court martial at the end of October and promoted, William Bligh had urged that a British ship of war be sent to apprehend the mutineers, and the Pandora had been charged with this mission. Edwards had sailed from Portsmouth on November 7, his orders to proceed to Otaheite. Should he fail to find the Bounty or any of her crew there, he was to make a search of the Society and Friendly Islands and bring home as many of the mutineers as he might apprehend.

He had discovered fourteen of them—two were midshipmen—in Otaheite. With impatient fingers Captain Edwards flicked through the pages of his journal in search of the entry. Slowly he read aloud:

Matavai Bay, Wednesday, March twenty-third, 1791 ... the armourer of the Bounty, Joseph Colman, attempted to come on board before we had come to anchor. He was followed, after we had done so, by George Stewart and Peter Heywood, late midshipmen of that ship, before any boat had been put ashore ...

His mouth hardened as he recalled that first meeting. They had faced him, looking, with their half-naked bodies and heavy tattoos, more like natives than English seamen, claiming that they had had no part in the mutiny. Young Heywood, in particular, had attempted to play the innocent, insisting that he could vindicate his conduct. He had had the effrontery to ask to see his onetime shipmate on the Bounty, Thomas Hayward—now third lieutenant of the Pandora—but Hayward had treated him with the contempt he fully deserved.

Captain Edwards passed a hand through his thinning red hair and sighed as he recalled the scene. He had scant sympathy with mutineers having, in his first command, been called upon to suppress an attempt to seize his ship, and he had ordered all three of the Bounty’s, rogues to be taken below and put in irons. Later, the rest of the scurvy crew had given themselves up, but four—Ellison, Muspratt, Millward, and Burkitt—were captured only after a chase by the Pandora’s pinnace and launch. They had endeavoured to make their escape in a small schooner they had built themselves, but were compelled to abandon their ill-constructed vessel at Paparre, on the far side of the island, and surrender to a landing party led by his first lieutenant.

Again Captain Edwards turned back the pages of the journal, to refresh his memory, this time as to his orders. Yes, there it was, in plain black and white, the entry copied from the Admiralty Commissioners’ official instructions.

On their being apprehended, you are charged to keep the mutineers as closely confined as to preclude all possibility of their escaping having, however, proper regard for the preservation of their lives, that they may be brought home to undergo the punishment due to their demerits.

The punishment for men found guilty of mutiny when serving in the Royal Navy was death. They were hanged from the yardarm in view of the whole fleet, to serve as an example to any who might be tempted to rebel against naval discipline. He had carried out his orders to the letter, the Pandora’s commander thought with grim complaisance.

Edwards had had a round-house built on the after part of the quarterdeck, eleven feet in diameter, to which entrance could only be made through a scuttle, some eighteen inches square, on the roof. The prisoners were confined there in fetters, secured by leg-irons shackled to strong wooden bars. It was the healthiest place in the ship, according to the surgeon, George Hamilton.

No escape attempt was made, but since there was always a danger of it, the captain had kept all fourteen of the mutineers in their wooden prison while, in obedience to his orders, he pressed on with his search for the Bounty. An abortive search, as it had proved. Captain Edwards gave vent to an exasperated sigh. Fletcher Christian and his piratical crew had seemingly spirited the Bounty into hiding in some far-off, uncharted part of the vast Pacific Ocean, and the prisoners—whether or not they were telling the truth—had, from the outset, professed ignorance of her destination.

They spoke freely of Christian’s proceedings immediately after he had cast Captain Bligh and his people adrift, recounting in detail the unsuccessful attempts Christian had made to set up a settlement initially on the island of Tubuai and then at Tongatapu, in the Friendly group. Both had failed, owing to the hostility of the natives. In consequence, quarrels had broken out among the mutineers, which had culminated in the decision of the men he had apprehended to return to Otaheite, in order, as they obstinately insisted, to await the arrival of a British ship.

‘To which, sir,’ young Stewart had stated repeatedly, ‘it was always our intention to give ourselves up. We are not mutineers, sir. We were detained on board the Bounty because there was not room enough in Captain Bligh’s launch for us to accompany him.’

Re-reading the page on which this statement had been punctiliously recorded, Captain Edwards swore under his breath. The damned young rogue! He and Heywood were King’s officers, and whatever they might claim, they had both disgraced the uniform they had once been privileged to wear. They had made no attempt to regain possession of the Bounty from Christian; instead, they had permitted themselves to be set ashore at Otaheite and had lived there, as natives, for almost two years—in adulterous association with native women, most of them even fathering children!

From the deck above he heard a shout from the leadsman in the chains. He could not make out the man’s words but, detecting a note of alarm in his voice, instinctively stiffened. Then, shrill and clear in the sudden silence, the mast-head lookout hailed the deck.

‘Breakers dead ahead, sir!’

The Pandora’s captain seized cap and glass and made at a shambling run for the companion ladder outside his cabin. The second lieutenant, Corner, was on watch, and he acted with commendable promptitude, yelling to the quartermaster to put his helm down and attempting to back the fore-topsail to check her way. He was too late; before the startled men of the duty watch could haul taut the tacks, the ship struck with a shuddering lurch on the treacherous coral reef and was held there, as if in a vice. As Captain Edwards reached the deck the leadsman’s call confirmed his worst fears.

‘By the mark three, sir—an’ shoaling!’ Then, a moment later, ‘A quarter less two, sir!’

She was aground, Edwards knew, but there was a chance that he might get her off. If only her bow had taken the ground, she might break free, though heaven knew with what damage to her hull and the copper in which it was sheathed.

‘Call the watch below, Mr. Corner,’ he rasped, as more hands tailed on to the sheets and braces in response to his shouted orders. ‘Mr. Saville, go below with the carpenter and report back to me if she’s making water. Look lively, boy, I want the well sounded without delay!’

The off-duty watch turned up, First Lieutenant Larkin at their head, Hayward at his heels, and both in their shirtsleeves, clearly just roused from their hammocks by the pipe.

Larkin said as he struggled into his watch-coat, ‘Wind’s dropping, sir. Shall I—’

Edwards did not let him finish. Brace his yards and trim his sails as he might, the Pandora had not shifted a foot, and now she was listing heavily to larboard and must be relieved of the weight of her top-hamper, lest she capsize. Lieutenant Saville, hurrying to his side to report that the carpenter had found four feet of water in the hold, decided him.

‘Send down to gallant yards and masts, Mr. Larkin,’ he ordered brusquely, ‘and I want the launch and pinnace hoisted out. We’ll send out an anchor and try to warp her off. Take charge of the boats, Mr. Hayward, and rig a transporting line to the kedge anchor. Jump to it! There’s no time to be lost.’

Apprehensively, Captain Edwards glanced astern; the light was fading rapidly. In a matter of minutes it would be dark. Raising his speaking trumpet to his lips, he bawled an order to Lieutenant Corner to set all spare hands to man the pumps.

The topmen swarmed aloft, needing no urging, for all were aware of the danger threatening their ship and their lives. In these lonely unfrequented waters, there was scant chance of aid reaching them from a passing ship. With the topmasts down and the guns of the larboard battery pitched overboard, the list became less acute, but the carpenter’s next report, again delivered by Lieutenant Saville, sent the captain’s briefly rekindled hopes plummeting.

‘She’s made eighteen inches in the last five minutes, sir, and the water’s gaining fast. The bottom’s been torn out of her for six feet or more on the larboard side and—’ He was interrupted by a harsh, grating sound, and the ship lurched wildly, almost jerking the feet from under him. ‘I’m sorry, sir, I—’

The captain was not listening. He steadied himself, cursing. The swell was driving her farther onto the reef, he realised; there was no hope now that she could be warped off. The wind, which had dropped at the very moment when he had needed its aid most, had veered and was rising, its blustering force increasing the pressure of the swell on the frigate’s exposed stern. He sent Saville below, with orders to set what men he could find to aid the carpenter to make repairs, and went grimly to consult with his first lieutenant as to what further measures might be taken to save the ship.

Larkin said, his tone guarded, ‘Sir, the prisoners—’

‘What about the prisoners, Mr. Larkin?’

‘They are alarmed, sir. Three or four of them have slipped their irons, and they are begging to be set at liberty to—to take their chance with the rest of us. They’ve all volunteered to aid us in working the pumps, sir, if you could see your way to releasing them.’

‘Release them?’ Captain Edwards exclaimed savagely. ‘No, by God, I will not!’ All the bitter frustration he was feeling at the prospect of losing his ship welled up like bile in his throat. But for the accursed scoundrels from the Bounty he would not have been in this precarious situation. Damn them, they were villains, for whom death was a fitting reward ... here or in England, it mattered little to him where they met their fate. Besides—he stiffened as the thought suddenly occurred to him—were he to release them now, they might seize one of the boats and make their escape, leaving his own men without the means to preserve their lives should the ship go down.

The captain raised his voice to shout for the master-at-arms to attend him. When the man came, he said coldly, ‘I’m informed that some of the mutineers have broken out of their fetters. See to it that all are properly secured. The sentries are to shoot any man who attempts to break out of the round-house. Is that clear? Then pass the word to them.’

‘Aye, aye, sir,’ the master-at-arms acknowledged. He was a taut hand, accustomed to discipline since it was his duty to see it enforced; but unable to hide his shock at the harshness of the order he had been given, he ventured a protest. Captain Edwards wrathfully waved him to silence.

‘Do as you are ordered, master-at-arms. I shall hold you responsible if—’

Lieutenant Larkin put in urgently, ‘Sir, the for’ard pump has broken down—the piston’s seized, sir. And I’ve no spare hands to relieve the others. Sir, the prisoners’ help would be of great assistance.’

The captain considered the suggestion, but before he could reply, he felt the deck cant steeply beneath his feet. The ship shuddered from stem to stern, and the crash of mangled timbers rang in his ears ... Wind and the incoming tide had beaten her over the reef. She steadied and then began to settle sluggishly in deeper water.

‘Let go the small bower, Mr. Larkin!’ Edwards ordered thickly. ‘Mr. Corner—I want soundings taken. Hail Mr. Hayward in the launch and tell him to row round to the larboard bow.’ He gave his instructions with a semblance of calm but with a sinking heart. It was of no surprise when Hayward reported the bow stove in below the waterline and fifteen fathoms underfoot. With two anchors out the ship held, but when Saville came running breathlessly to tell him that there were now eight feet of water in the hold, he knew that there was little more that he could do to save her. More guns were hove over the side and a thrummed topsail prepared to haul under the ship’s bottom, but the water was gaining at an alarming rate, the men at the pumps dropping with exhaustion. Reluctantly, Captain Edwards sent for the master-at-arms again.

‘You may release Colman, McIntosh, and Norman and set them to work at the pumps,’ he rasped. ‘Are they all secured in irons?’

White-faced and tense, the master-at-arms inclined his head. ‘They are, sir.’

‘Then they are to remain so. The officers are not to be released, d’you understand?’

‘They’re pleading with you for mercy, sir,’ the petty officer said. ‘When Hodges and I were locking the irons on them, like you ordered, sir, before she went over the reef, they was begging us to intercede with you. Midshipman Heywood’s only a boy, sir—Ellison too. And Byrne, the fiddler—he’s almost blind and simple with it. Why—’

Edwards cut him short. In the dim light his expression struck chill into Master-at-arms Jamieson’s heart, and involuntarily he stepped back a pace.

‘Carry on, Jamieson,’ the captain’s voice cut like a whiplash, brooking no argument, ‘unless you want me to take your rate from you. We’ve not lost the ship yet.’

‘Aye, aye, sir,’ the master-at-arms responded woodenly. He summoned Armourer’s Mate Hodges, and together they climbed onto the roof of the round-house, known to the lower deck as ‘Pandora’s Box’. The marine sentry posted at the scuttle greeted them with undisguised relief.

‘Come to let them poor devils out, ’ave yer, Master-at-arms? About time too, I reckon.’

Jamieson shook his head. ‘Only three of ’em. The rest are to stay here—captain’s orders.’

The sentry stared at him aghast. ‘But she’s goin’ down any minute, ain’t she? I ’eard the first lieutenant order the other two boats lowered ten minutes since.’ He shivered. ‘Wish I was in one of ’em.’

‘The captain doesn’t reckon she’s lost, lad,’ Jamieson told him glumly.

Hodges had the scuttle open, and the two of them lowered themselves onto the round-house in turn. Within its confines, the stench was appalling. The fourteen wretched prisoners had been kept there, chained hand and foot and deprived of exercise, since the ship had left Matavai Bay. There they had remained during the four month search for the Bounty.

Unwashed and verminous, they crouched semi-naked on the bare deck planking, wrists and ankles firmly chained. The tubs they used for their necessary bodily functions were removed and emptied once weekly, but that was all. A few buckets of seawater, occasionally flung into the round-house, was the only concession to their hygiene Captain Edwards had permitted.

The poor sods were as weak as kittens, the master-at-arms thought pityingly. If the ship did go down they would stand little chance of swimming to safety, even if the captain relented and ordered their release. The nearest cay was about four miles distant. He jerked his head at Hodges, and the armourer’s mate started to strike off Joseph Colman’s leg irons.

‘Are you letting us out, Mr. Jamieson?’ Midshipman Stewart asked in a low, controlled voice. He was twenty-three, dark-haired and slender, with a large, gaudily coloured star tattooed on his chest.

Jamieson, unable to meet his gaze, shook his head and answered gruffly, ‘Just Colman, McIntosh, and Norman—they’re to help on the pumps. I’ve no orders for the rest of you.’

‘But she’s foundering, for God’s sake! Are we to be left to drown like rats in a trap?’

‘And what about poor Byrne?’ Midshipman Heywood put in bitterly. The fiddler crouched beside him, his blank, blind eyes moving this way and that, as if seeking in his own greater darkness for some clue as to what was going on beyond his ken. Heywood’s hand clasped his, offering comfort. ‘You know he can barely see, Mr. Jamieson—give him some chance, can’t you? Whatever the captain says, Byrne’s no mutineer.’

Hodges had released Norman, the carpenter’s mate, and was ushering the three who had been ordered to the pumps up through the narrow opening of the scuttle. Jamieson sighed. He knew his duty and also knew only too well what any dereliction might cost him. Captain Edwards was a cold-blooded martinet, and in a British ship of war the captain’s word was law. His orders—however inhumane—must be obeyed, on pain of flogging or worse. But in the faint light of the lantern he carried, the master-at-arms studied the two faces upturned to his and pity triumphed over discretion. Heywood was not yet eighteen, his cheeks innocent of stubble, a handsome, blue-eyed boy with all his life before him. And as for Byrne ... why, the poor fellow did not even know what time of day it was. Jamieson bent and inserted his key into the lock of Byrne’s wrist fetters, aware that the man was so emaciated that he would have no difficulty in freeing his bony ankles from the leg-irons.

‘I can’t let you out, Mr. Heywood,’ he said. ‘The captain was most particular—the officers aren’t to be released. Those was his orders.’

‘What about us?’ Thomas Burkitt demanded hoarsely. He swore loudly and angrily, his pock-marked face contorted. ‘We ain’t bleedin’ officers, Mr. Jamieson, an’ this stinkin’ ship’s goin’ down, as well you know!’

‘Mamoo, Tom!’ Midshipman Stewart warned, using the native tongue of Otaheite. He turned to the master-at-arms and asked gravely, ‘Mr. Jamieson, for the love of God, will you come back and release us if she is going down? We have a right to a trial. Captain Edwards cannot condemn us out of hand. He—’

The tall petty officer bowed his head. ‘I’ll come back, Mr. Stewart,’ he promised. ‘I’ll not leave you to drown.’ Cutting short Burkitt’s protests, he levered himself out of the scuttle and slammed the grating shut behind him.

Left alone in their malodorous darkness, William Muspratt, who had been involved in the mutiny on board the Bounty from its outset, started to weep.

‘We should have gone with Mr. Christian an’ the others. We should’ve stayed with the old Bounty. Cap’n Bligh was bad enough, God knows, an’ we thought he was goin’ out of his mind, starvin’ an’ floggin’ us. But this Cap’n Edwards, rot him—he’s a bleedin’ monster! Ain’t he got no pity, no feelin’s at all?’

‘It would seem he has not,’ Stewart said dryly. He was cool and wonderfully calm, and young Peter Heywood took courage from his stoicism.

‘Do you suppose Jamieson will keep his word, George?’ Heywood asked, lowering his voice to a whisper.

George Stewart answered with conviction, ‘Jamieson is a good man. If the ship is in serious danger, he’ll let us out if he can. And they may save her yet—you heard what he said to the sentry.’

‘Yes, but they’ve lowered the boats, lowered all of them, the sentry said so. If they’ve done that, then—’

‘Edwards was just taking precautions. He hasn’t ordered any provisions to be loaded into them yet, has he? We’d have heard if he had.’ Stewart was struggling with his leg-irons. ‘Lord, Hodges made a job of these when he put them back on! How are yours, Peter?’

‘Tight,’ Heywood admitted ruefully. He tapped Byrne’s knee with one of his manacled hands. ‘Try and work your legs free, Michael, and then see if you can pull the bar out for the rest of us. Go on, lad.’

‘We ought to be praying, Mr. Heywood,’ the blind man objected.

‘We’ll pray a whole lot better if we’re free of these blasted irons!’ Burkitt told him. ‘Go to it, yer little swab—you’re the ony one that can.’

‘I got to pray for forgiveness, Tom,’ Byrne answered apologetically. His misted eyes sought Muspratt. ‘I’ll pray for you, Will, along with myself.’

Will Muspratt swore at him. ‘Tell ’im ter do what Tom says, Mr. Heywood—he’ll listen to you.’

Hillbrant, the Hanoverian, said in his strongly accented voice, ‘It is of no use to ask him, Will—not until he is done with his praying. And he is right ... All of us should pray, for it seems to me only Almighty God can help us now. You are the senior officer, Mr. Stewart ... will you be so good as to lead us in prayer?’

Thus appealed to, George Stewart did his best, reciting first the Lord’s Prayer and then all he could remember of the prayer for those in peril of the sea. They all joined in, even Burkitt and Muspratt; then Byrne, still anxious to intercede for forgiveness, offered a prayer of his own, which went on so interminably that John Sumner—one of the hardcore of the Bounty mutineers—who had hitherto maintained a sullen silence, struck the blind man viciously across the face with his manacled fist.

‘Pipe down, yer pulin’ little bastard!’ he exclaimed impatiently. ‘And start workin’ these bars so’s we can get our leg-irons unhitched before this plaguey ship takes us down with her. You—’

‘Leave him be, John,’ Heywood interrupted.

The note of authority in his voice annoyed Sumner; he sneered openly at the one-time midshipman, his scarred, heavily bearded face ugly in its resentment.

‘And you c’n pipe down, Mr. Heywood! ’Cause you ain’t an officer no more—you’re a bloody mutineer like the rest of us.’

‘You know that’s not true,’ Heywood protested.

‘Accordin’ ter Captain Bleedin’ Edwards it is. He don’t treat you no different from me or Burkitt or Muspratt, does he? He treats you worse than he does us.’

George Stewart wearily intervened. He had been indulging himself in his usual daydream during Byrne’s lengthy prayer—recalling happy, unforgettable memories of his life on Otaheite: the love of the native girl he had taken to wife and called Peggy, the birth of their infant daughter, the warm friendship and loyalty her family had given him, and, above all, the pleasant, undemanding existence he had led in a place that now seemed nearer to paradise than anything he had previously experienced. And it was gone, lost to him forever, as were Peggy and the child ... He smothered a sigh.

What the devil did it matter if the Pandora did go down and take them with her? It would be over; they would at least be spared the rest of the long voyage in this foul cage. They would not have to endure the humiliating ordeal of the court martial that must, inevitably, await them on their return to England, and the shame it would bring upon their families if they were unable to prove their innocence.

‘Have done, Sumner,’ he said sharply. ‘The lad’s doing the best he knows how.’ His voice softened as he turned to speak to Byrne. ‘There now, Michael lad, you’ve made your peace with God, and I’m sure in His infinite wisdom He will know that you are truly repentant and will look upon you mercifully.’

‘Will He, Mr. Stewart?’ the blind boy echoed eagerly. ‘Oh, thank you, sir. I was worried, see? But I’ll get me legs out, like Sumner wants, and—’

With a harsh grinding sound, the stricken ship freed her stern from the coral of the reef and began to sink, with a heavy list to larboard as the water rushed in through her lower-deck ports. Shouts and the pad of bare feet on the deck planking brought the prisoners’ heads up, all of them listening intently in an effort to interpret the sounds reaching them from outside their cage.

The senior rating, a boatswain’s mate named James Morrison, whose eyes had been closed in silent prayer long after Byrne had been called upon to desist, moved awkwardly to a split in the planks, through which a restricted view of the quarterdeck could be obtained.

‘One o’ the pumps ain’t working,’ he said disgustedly. ‘And they’re preparin’ to hoist out them two native canoes the cap’n bought in Samoa ... lashin’ ’em together. It don’t look good, boys. I reckon they’re gettin’ ready to abandon ship.’

‘What about us?’ Burkitt growled. ‘Damn their eyes!’ He started to call out to the sentry who bent, musket at the ready, to enjoin silence.

‘Ain’t you got orders ter let us out?’ Burkitt demanded furiously.

‘No, I ain’t—only ter shoot you if you try ter rush me.’ The marine sounded frightened, though whether of them or of the situation of the ship it was impossible to tell. But he added, taking pity on them, ‘She’s down by the head, but she’s still afloat. Mr. Corner has a party tryin’ ter haul a sail under her bottom ter stop the leak, an’—’

‘A hell of a lot of good that’ll do, wiv’ ’arf her bottom torn out an’ the pumps failin’!’ Burkitt retorted bitterly. ‘Bloody Jolly—you’ll be all right if she founders, but we shan’t! Why—’

George Stewart again, almost with reluctance, intervened. ‘Stow your gab, Burkitt,’ he said curtly. And to the sentry, ‘Do this for us at least, lad—unless you want our deaths on your conscience—if the order comes to abandon ship, open the scuttle before you quit your post.’

‘I’ll do what I can, Mr. Stewart,’ the marine conceded. He withdrew his head, straightened up, and, shouldering his musket, resumed his measured pacing on the roof of the cage.

The hours dragged past, with every sound from the deck adding to the prisoners’ torment. Stores were being loaded into the boats; Lieutenant Corner’s party had abandoned their efforts to haul the thrummed topsail under the hull, but a loud crash from forward suggested that the foremast had been cut away in an attempt to lighten her. Two pumps were still working, but it was evident, from snatches of overheard conversation between the men on the deck and the swish of water across the forecastle, that they were barely keeping pace with the inrush of water from below.

Byrne had at last contrived to free his legs from their shackles. Urged on by Burkitt and Muspratt, he was vainly endeavouring to lever out one of the two wooden bars to which the leg-irons of the others were secured.

Moving closer to Stewart, Peter Heywood whispered, ‘George, Captain Edwards will relent, won’t he? Before she goes down, I mean?’

His fellow midshipman shrugged. ‘Who knows?’ He sounded curiously resigned, almost indifferent, as if he had ceased to care what fate had in store for them, and Peter Heywood stared at him in open-mouthed dismay.

‘Doesn’t it matter to you?’ he challenged. ‘Are you—are you not afraid to die?’

Stewart shook his head. At that moment, he seemed much older than his twenty-three years, and there was a note of disillusion in his voice as he answered quietly, ‘I think I prefer death to what would otherwise be in store for us, Peter. If Edwards’s treatment is an example of what we may expect, then I want no part in it. Least of all do I want to face a court martial in England.’

‘But we’re not mutineers—you and I—nor are most of us, come to that. Bligh’s boat would have been overloaded if he’d taken us with him, and he gave his word—his solemn word, George—that he would see that justice was done to those of us who remained with Christian against our will.

They had talked of those last moments—when Captain Bligh’s launch had put off from the Bounty—a hundred times without reaching any useful conclusion, and Stewart repeated his shrug. ‘Bligh must have changed his tune, once he reached England—tarred us all with the same brush, I fear.’

‘I was afraid to go with him,’ Heywood admitted shamefacedly. ‘Even if I’d been given the chance to go, I cannot be sure that I would have taken it. But that doesn’t make me guilty of mutiny, does it? I never raised my hand against him.’ He waited, but when Stewart was silent, he burst out, ‘Now, when I am facing the imminent prospect of death, I can tell you the truth, George ... I hated Bligh! He—’

‘No need to speak of such matters in the hearing of others,’ Stewart put in gently, ‘even if we are facing death.’ He gestured in the direction of the boy, Ellison, who was craning his head in an attempt to hear what they were saying, and sharply bade him go to Byrne’s aid. ‘Tom Ellison would have shot Bligh if Christian hadn’t prevented it. He had good reason, too, you know ... and Christian had the best reason of all to want Bligh dead.’

Remembering the last words Fletcher Christian had spoken to him, when they had parted on the shore of Matavai Bay almost two years before, Heywood caught his breath.

When a British ship comes—as one surely will, Peter—give yourselves up at once, you and George. You are both innocent—no harm can come to you, for you took no part in the mutiny. It is different for me—I must run for the rest of my life, for William Bligh will never rest until he finds me. I must cover my tracks well ...

There had been other confidences, other admissions, together with messages for his family entrusted to him by Christian, before the Bounty weighed anchor and bore away, to leave Otaheite behind her forever. Heywood glanced uneasily at his friend. ‘George, I—’

George Stewart said in a low voice, deeply charged with emotion, ‘Captain Bligh is a madman. One day, if he is permitted to go on living, his madness will manifest itself for all to see. He’ll no longer be able to conceal or control it, and then God help those who stand in his way! The pity of it is that for us—’

He broke off, a stream of orders shouted from the deck freezing the words on his lips.

‘Abandon ship! D’ye hear there—abandon ship! All hands make for the boats!’ The captain’s voice, harsh with despair, echoed from end to end of the doomed ship. ‘Stand by to pick up swimmers, Mr. Hayward!’

Booted feet thudded on the roof of the round-house, as Edwards himself, with two other officers at his heels, used its elevation in order to ensure that his instructions were obeyed. The concerted cries of the prisoners, pleading desperately for release, met with a curt response they could not hear above their own clamouring, and a moment later, all three officers had gone, only Robert Corner pausing to call out to them that the order had been given to set them free.

The ship lurched over onto her larboard side, flinging them this way and that, and as they were picking themselves up, cursing and tearing at the chains that held them, the scuttle was unbarred and the face of the master-at-arms appeared in the aperture.

‘Captain’s orders, my lads,’ he told them. ‘Byrne, Muspratt, and Skinner are to be let out of irons. Make way, there—the armourer’s coming down,’ he added crisply. Burkitt voiced an angry protest at his own omission and young Ellison, beside himself with fear, tried to thrust past the descending Hodges.

The armourer’s mate cuffed Ellison out of his way and set stolidly about his task. Byrne, already free, was assisted out through the scuttle, sobbing his relief; Muspratt followed, but Skinner, too panic stricken to wait for his fetters to be unlocked, was hauled up with his hands still pinioned.

And then, to the shocked dismay of those who were left, the scuttle was again slammed shut, leaving Hodges still imprisoned with them. He gave them a wry grin and went on knocking off the leg-irons of the men nearest to him, his stoical display of courage putting even Burkitt to shame.

‘The jaunty’s only obeyin’ orders, boys,’ he offered reassuringly. ‘Waitin’ till the captain’s gone over the side.’

‘He has now,’ Morrison asserted, peering out through his accustomed spyhole. ‘I can see the bastard swimmin’ out to the pinnace and the first lieutenant after him. Rot ’em, the scurvy swine!’ Freed of his chains, he made for the space beneath the scuttle, and his voice took on a frantic note of urgency as he besought Jamieson not to desert them. ‘For God’s sake open up an’ let us out! The captain’s gone—all the officers have, damn them to hell!’

‘An’ we need the key to our ’andcuffs,’ Burkitt yelled.

‘Never fear, my boys, I’1 not leave you—we’ll go to hell together if we have to,’ the master-at-arms responded stoutly. The scuttle opened and he dropped his key into Morrison’s eagerly waiting hands. ‘I’ll have the lot of you out in—’ his voice trailed off into a cry of anguish. The ship, her bows awash, turned over onto her larboard side, hurtling him into the sea, the sentry with him.

From the hovering boats there rose a shout calculated to strike terror into the hearts of all who remained, ‘There she goes! That’s the end of her!’

Water was pouring into the cage now, and as the key was passed from hand to hand, even the freed men were struggling waist-deep in it, seeking to haul themselves out through the scuttle before it closed over their heads.

Unable to disentangle his leg-irons from the bar to which they were shackled, Peter Heywood resigned himself to certain death. He offered up a despairing prayer and then, as if by a miracle, it was answered. The bar slid away and he saw that one of the Pandora’s marines, a big, powerfully built corporal named Hawley, was beside him, tugging the bar through the shackles with the aid of a man who clung to the hatch coaming, up to his neck in water—Will Moulter, a boatswain’s mate.

‘Out you go!’ Hawley urged breathlessly and thrust him in the direction of the open scuttle.

‘God bless you, Hawley—God bless you both!’ the midshipman managed hoarsely.

Moulter hauled him out into the sunlight he had thought never to see again and yelled to Hawley to follow him.

The deck was awash and deserted, but the boats, Heywood saw, were standing by, their crews picking men up from the water. He dove without hesitation over the stern to strike out for the nearest boat; but he was naked and weak from his long incarceration, and it was all he could do to keep himself afloat. He was thankful to see a plank, to which he clung with desperately clutching fingers.

All round him were bobbing heads, and cries of the men who could not swim echoed like a knell of doom in his ears. One poor fellow attempted to share his plank but went under before Heywood could put out a hand to help him. He reached the longboat and was lifted into it, to lie gasping and retching up seawater on the bottom boards, too weak even to murmur his thanks.

Recovering at last, Heywood sat up and turned to look apprehensively over his shoulder. There was nothing to be seen of the Pandora but her mainmast crosstrees, and now there were only a few bobbing heads in the water, all bunched together close to where the ship had gone down. The launch was pulling towards them, urged on by Lieutenant Corner, the crew pulling frantically at their oars, and he thought he recognised Corporal Hawley among the swimmers. The pinnace, almost on the point of foundering from the weight of the men crowded into her, was heading for the nearest cay, with the longboat, also crowded, just astern of her.

Lieutenant Hayward—his one time shipmate and friend on the Bounty—motioned the newly rescued midshipman to join him in the stern sheets. Regarding him with more sympathy than he had hitherto shown, Hayward said, ‘You were fortunate, Peter. We have lost a lot of men—George Stewart among them. He—’

Peter Heywood stared at him, shocked. ‘You mean George drowned? But he got out of the Box before I did—I saw him. And he was a good swimmer, Tom. Don’t you remember, he—’

Tom Hayward cut him short. ‘He and another of the prisoners—Sumner, I think—were struck by a grating which fell or was thrown from the ship. They sank before we could reach them. Perhaps it was for the best—who knows?’ He shrugged and did not address Heywood again until the boat grounded on the cay.

The cay was small and devoid even of bushes, and as the sun rose, the men—particularly those who had swallowed seawater—began to experience the torments of unassuaged thirst. Captain Edwards doled out water very sparingly from the casks contained in the pinnace and set a guard over these and over the surviving prisoners, who were permitted only half rations.

When the launch joined them, he ordered Lieutenant Larkin to call the roll, which revealed that thirty-four officers and men were missing. They included four of the Bounty prisoners—George Stewart, Sumner, Skinner and Hillbrant—young Lieutenant Saville, and to Peter Heywood’s heartfelt regret, the man to whom they owed their lives, the master-at-arms, Ben Jamieson.

Light headed and miserable as the sun beat mercilessly down on his naked body, Heywood crouched on the sand, taking no more than a cursory interest when the captain, having taken stock of the provisions brought ashore, announced that he intended to make for Timor in the boats as soon as the men were sufficiently recovered from their ordeal.

Boats were sent back to the wreck—more in the hope of salvaging provisions than in the expectation of finding any of her missing people alive—and they returned with only a few spars and scraps of sailcloth to show for their efforts. With these and a sail from the launch, Captain Edwards ordered shelters to be set up, but the ten Bounty prisoners were sternly forbidden their use.

‘The bastard wants to put an end to us,’ Morrison asserted bitterly when even his plea for a tattered remnant of canvas, lying unwanted on the shore, was curtly refused. ‘Why don’t he hang us an’ have done?’

No one answered him, but Tom Ellison observed with equal bitterness that Hillbrant had gone down with the ship, still in his chains. ‘I reckon that was what the swine wanted to happen to the lot of us. Hodges says Edwards ordered the soddin’ hen coops put overboard before he was sent in to let us out!’

Three days later, on September 1, the ninety-eight survivors of the wreck were divided among the Pandora’s four boats, and Captain Edwards set course for Timor, estimated at more than a thousand miles away.

Their provisions were meagre—a few bags of ship’s biscuit, three small casks of water and one of wine—the daily ration being the equivalent of two wine glasses of water a man, with the addition of a small quantity of biscuit, which most of them were too parched to swallow.

For the prisoners in the captain’s boat, the sixteen-day voyage was well-nigh unendurable. Peter Heywood, as the only surviving officer from the Bounty, became the butt of Edward’s ill humour, addressed always as a ‘piratical villain’ and kept with his ankles firmly bound, even when ordered to take his turn at the oars. Off the Mountainous Island they were attacked by natives and pursued by war canoes. Only on a few occasions were they able to land, to augment their supplies with shellfish and to top up their depleted water casks.

All were exhausted and near to starvation when, on the morning of September 16—having sighted the island two days earlier—the little procession of boats entered the Coupang anchorage. Captain Edwards went ashore, accompanied by the first lieutenant, to wait on the Dutch Governor, and within two hours of his departure, permission was given for the Pandora’s people to land.

There were two Dutch soldiers with Lieutenant Larkin as Peter Heywood stumbled onto the quay. Larkin flatly told Heywood and the other prisoners, ‘You’re all to be taken to the fort and held there until the captain can arrange transport to Batavia.’

Heywood looked about him dazedly. The pleasant, white-walled houses of the Dutch settlement ringing the bay were, he saw, overshadowed by the towering fort; guns were mounted to cover its sea approaches ... and doubtless it was furnished with dungeons, deep below its formidable walls, for the accommodation of prisoners such as himself. His head drooped as one of the soldiers grasped his arm.

‘You’ll not be the only British prisoners,’ Larkin told him, not unkindly. ‘Eleven escaped convicts from the penal settlement at Sydney Cove in New South Wales sought refuge here some weeks ago. They made the voyage in a twenty-three-foot lug-sail cutter, incredible though it may seem.’ He sighed, his expression relaxing a little. ‘Poor devils! Governor Wanjon has handed them over to our captain’s custody, and he has ordered them to be confined with you and the other mutineers. Fitting company, I hope, Mr. Heywood.’

He turned on his heel, and the Dutch soldiers took the weary party of Bounty prisoners up a long, sun-drenched road towards the fort.

Escaped convicts from a penal colony were, Heywood thought, indeed fitting company. Like his shipmates and himself they would face the death sentence when they saw England’s shores again.

The judge, a dignified figure in his scarlet robes, took his place on the bench, his bewigged head briefly lowered in response to the bows of counsel and the body of the court. The members of the jury resumed their seats, and then their concerted gaze returned to the five prisoners who, manacled and under guard, stood in the dock waiting for the charges against them to be read.

There were five of them—four men and a young woman of perhaps five-and-twenty in widow’s garb. All were deeply tanned, lacking the prison pallor of most of those brought to trial at London’s Old Bailey, but they were thin to the point of emaciation. The jurymen studied their faces with intense curiosity, aware—since it had been recounted at some length in the newspapers and talked of in the taverns—of the extraordinary story the prisoners had told following their arrival three weeks before. Committed to Newgate by magistrate’s warrant, they had received a sympathetic hearing at Bow Street but were now on trial for their lives before judge and jury.

There was a slight stir, as the well-known Scottish advocate, Mr. James Boswell—his wig a trifle askew—entered the court, made his belated bow to the judge, and then took his seat immediately behind the young barrister who had been appointed counsel for the defence.

The clerk of the court, the charge sheet in his hand, named the accused in turn.

‘If your lordship pleases ... John Samuel Butcher, who now wishes to be known by his rightful surname of Broome, James Martin, William Henry Allen, Nathaniel Lilley, Mary Bryant, born Mary Broad.’

The prisoners stiffened into rigidity, their faces devoid of expression. ‘You are charged with having, on the twenty-sixth day of March, seventeen ninety-one, absconded from the penal settlement at Sydney Cove, in the country of New Holland, whither you had been sentenced to transportation for crimes committed in this realm, of which each and every one of you had been adjudged guilty by a properly constituted court of law.’

Consulting his papers the clerk listed each of the previous sentences and the courts that had imposed them. With the single exception of William Allen—a tall, gaunt man in his mid-fifties who had been given life—their sentences had been for seven years.

After a brief pause the clerk went on, ‘You are further charged, severally and with others now deceased, with having stolen from its moorings in Sydney Cove a cutter, the property of His Majesty’s Government, for the purpose of absconding from the colony prior to the expiration, in each and every case, of the sentences previously imposed on you.’

Again he paused and then, addressing each prisoner in turn, demanded, ‘How say you? Are you guilty or not guilty of these charges?’

John Broome faced him, blue eyes suddenly ablaze in his handsome, sunburned countenance. Taller than the others, he drew himself up to his full height and asked defiantly, ‘Is it a crime to seek freedom from tyranny?’ The clerk did not answer him, and so Broome appealed to the judge, ‘Is it, my lord?’

‘Reply to the learned clerk’s question concerning the charges brought against you,’ the judge bade him severely. ‘Did you or did you not abscond from the penal settlement in New Holland before your sentence had expired?’

‘I did, my lord,’ the prisoner admitted. Some of the jurors murmured sympathetically, and he turned to flash them a grateful smile.

‘Then you must so plead, unless it is contrary to the advice given to you by learned counsel for the defence,’ the judge ruled. ‘You will be permitted to speak in mitigation at the appropriate time.’ He added curiously, ‘Was this your first attempt to escape?’

‘No, my lord. It was my third. The first two were unsuccessful.’

The judge’s white brows rose. ‘For which, no doubt, you were tried by the colonial court and punished?’

Broome inclined his head. He answered, aping the lawyers’s respectful parlance, ‘If it please your lordship, the colonial court sentenced Lilley and myself to two hundred lashes on each occasion. After receiving them, we were required to perform our public labour in leg and arm fetters for three months.’

The picture his words conjured up again won a sympathetic murmur from the jurors, which the judge quelled with a withering glance. Aware that he had allowed his curiosity to override correct judicial procedure, he commanded brusquely, ‘Make your plea, Butcher. Are you guilty or not guilty of the offences with which you are charged?’

Still defiant, the accused man did not lower his gaze. ‘Guilty, my lord,’ he returned. ‘If, in your lordship’s view, my actions constitute a crime. And my name is Broome, sir. That is the name I was born to.’

The other prisoners, sullen-faced, seemed about to echo his plea, but the judge intervened, advising them to consult their counsel. After a whispered exchange all declared themselves not guilty and were directed to sit.

Counsel for the crown began his opening address.

‘Me lud ... members of the jury ... the prosecution will show that the accused persons—all of them convicted felons previously deported to New Holland—together with four others of the same kidney, William Bryant, William Morton, Samuel Bird, and James Cox, now deceased, absconded in a stolen boat, in which they voyaged to the Dutch island of Timor, in the East Indies. Timor, me lud, is distant some three thousand miles from Sydney Cove, and the accused landed there on the fifth of June of last year ...’ The barrister glanced at the jury, allowing time for his words to sink in.

Mary Bryant’s thin cheeks drained of colour as he went on.

‘During the voyage they suffered no loss, but the husband of the prisoner Bryant and her three-year-old son—ah, Emmanuel—died subsequently of fever. On landing at Coupang, they endeavoured to pass themselves off as survivors of a shipwreck, but the Dutch authorities, who had received them with kindness and compassion, became suspicious. When one of their number, in a state of intoxication, revealed their true identities, they were placed under arrest.

‘On the arrival in Coupang of Captain Edward Edwards of the Royal Navy, whose ship—the frigate Pandora, me lud—had been lost in the treacherous Endeavour Strait, the prisoners were delivered into his custody by His Excellency Governor Wanjon, to enable them to be returned to this country.’

‘Is it your intention to call Captain Edwards to give evidence, Mr. Symes?’ the judge asked.

‘It is, me lud, should his evidence be required.’

‘Very well. Pray continue.’

Mr. Symes bowed. ‘Captain Edwards, as your lordship will recall, was dispatched to the South Seas by the Board of Admiralty to search for and bring back the mutineers who seized His Majesty’s ship Bounty, in April of the year seventeen eighty-nine in order that they might stand trial. It was following the successful conclusion of his mission, with fourteen of the mutineers on board, that the Pandora went down with the loss of some thirty-four lives. Captain Edwards reached Timor, with the survivors of his ship’s company and ten of the surviving mutineers in the Pandora’s boats, on the sixteenth of September of the previous year ...’ The deep, resonant voice droned on, but now John Broome was scarcely aware of what was being said.

A bitter rage flooded over him and he clenched his manacled hands convulsively at his sides. Edwards, he thought, Captain Edward Edwards of the Pandora—most cruel and vindictive of men!

Whatever harsh discipline Captain Bligh had imposed on the Bounty’s company paled into insignificance by comparison with the treatment Edwards had meted out to the unfortunates he had made captive in Otaheite. He had shared their imprisonment in the fort at Coupang and later in Batavia. Then he had made the voyage with them to the Cape in the Dutch Indiamen Hoornwey and Horsson, chained below decks on Edwards’s command, in conditions far worse than those that had prevailed in Governor Phillip’s convict fleet ... The courtroom faded.

John Broome—who had called himself Butcher during his years of exile in New Holland—was back in the stolen cutter, reliving the long ordeal whose full story would not, he knew, be told here. He glanced at Mary Bryant, pale now beneath her tan but dry-eyed and wonderfully composed. She met his gaze and smiled, and he marvelled at her courage.

Mary Bryant had endured the terror of storms that had come close to wrecking their frail craft; she had suffered near starvation and the awful pangs of thirst without complaint, seeking only to spare her children from such torments. She had baled with the rest of them when the boat had been swamped; had cooked when they ventured ashore and were able to light a fire; and had eaten raw fish and sea-bird meat when it had been too dangerous to show themselves on land. She had remained silent when the natives had launched savage attacks on them, heralded by a shower of spears or arrows from a pursuing war canoe. And she had lived, when death had claimed her little son and then her stalwart husband, Will—who had planned and made possible their escape, only to fall victim to the endemic fever that was the curse of the Dutch East Indies. His constitution was undermined and his will to live was snuffed out by Edwards’s calculated cruelty. For ten days in Batavia while the Pandora’s captain had wrangled with the Dutch officials over the price of their passages to the Cape, the prisoners—convict and mutineer alike—had been confined in the stocks, supposedly as punishment for insolence.

John Broome caught his breath in an attempt to fight down his anger. On the voyage to the Cape, James Cox had jumped overboard from the Hoornwey in the shark-infested Sunda Strait, and Will Morton and Sam Bird had died of the fever. But the cruellest blow of all had been the death of the Bryants’ infant daughter Charlotte—ironically on board H.M.S. Gorgon, when only a week’s sail from Spithead. (The prisoners had been transferred from Dutch hired vessels to H.M.S. Gorgon, homeward bound from Sydney, and brought to England to stand trial.) The Gorgon’s commander had treated all the prisoners well: Mary Bryant had been freed of her fetters and allocated a cabin, but the child had still died, and Mary, poor young soul, had been prostrate with grief ...

‘Wake up, Johnny—’e’s talkin’ about ’ow we made it to Coupang an’ ’e ain’t arf pilin’ it on! Makin’ us out ter be soddin’ ’eroes!’

His eyes had been closed, Johnny Broome realised ... He sat up, listening intently.

‘It has to be conceded, me lud,’ the prosecutor was saying, ‘that these people miscarried in an heroic struggle to regain their liberty, after having Combated every hardship and conquered every difficulty. Their voyage in an open boat, which they navigated across three thousand miles of perilous ocean, must rank with that of the much esteemed Captain Bligh. For this reason, if your ludship pleases, the crown is not demanding the death penalty that is usual in such cases.’