Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Steven Schwankert thought there were no new Titanic stories to be told – then he found the Six. When Titanic sank on a cold night in 1912, less than half of those aboard survived. Among these survivors were six Chinese men. Unlike their Western counterparts, upon reaching solid ground in New York these men were almost immediately expelled from the country and, to some extent, the history books. Now at last their stories can be told. The result of meticulous research, dogged investigation and personal interviews, The Six is an epic journey of research that crosses continents to reveal the tales of these six forgotten survivors. Their names were Ah Lam, Chang Chip, Cheong Foo, Fang Lang (or Fong Wing Sun), Lee Bing and Ling Hee. Were they heroes? Were they cowards? Or were they just lucky?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

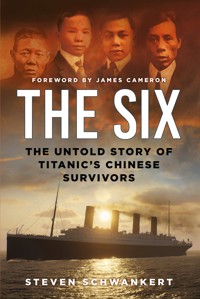

RMS Titanic.(HFX Studios – Alex Moeller and Tom Lynskey, model by Vasilije Ristović)

Cover images:

RMS Titanic. (HFX Studios – Alex Moeller and Tom Lynskey, model by Vasilije Ristović)

Headshots left to right:

A CR10 seaman’s identity card for Lam Choi, believed to be the Titanic survivor Ah Lam. (The National Archives 356009)

A possible image of Titanic survivor Lee Bing, reproduced from a glass plate, c. 1920. (Courtesy of the Cambridge City Archives, Cambridge, Ontario)

A photo of Fong Wing Sun, believed to be Titanic survivor Fang Lang, c. 1920. (Courtesy of the Fong Family)

A CR10 seaman’s identity card for Yum Hee or Yum Hui, believed to be the Titanic survivor Ling Hee. (The National Archives 261023)

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Steven Schwankert, 2025

The right of Steven Schwankert to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 785 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Contents

Foreword by James Cameron

Notes on Measurements and Romanisation

Introduction

Section I

1 A Piece of Wood

2 The World in 1912

3 From the Four Counties to the World

4 The White Star Line

5 RMS Titanic

6 Escape

7 Cowards, Stowaways and Women

8 Collapsible C

9 Excluded

10 Scattered to the Four Winds

11 Ling Hee, Ah Lam and Cheong Foo

12 Lee Bing: The Canadian

13 Fong Wing Sun: The American

14 The Seventh

Section II

15 The Search for the Six

16 Changing Course

17 Tackling Titanic

18 Finding Fong Wing Sun

19 A Tale of Two Tales

20 Watertight

21 The Six

Acknowledgements

Bibliography and Sources

Notes

For QX

Foreword

When I made my film Titanic and told the story of fictional Third-Class passenger Jack Dawson, there was another storyline I filmed and wanted to include. And that was the real-life rescue of a Third-Class passenger, a Chinese man found floating on a piece of wreckage. That man’s grit and determination to survive and my admiration for him inspired the now-famous Jack and Rose ending to Titanic.

Steven Schwankert and the researchers behind the award-winning documentary The Six have brought a little-known aspect of Titanic history and the Chinese experience overseas vividly to life. A historian who has spent the last quarter-century exploring China’s lakes, rivers and seas, and plunging into the country’s rich maritime history, Schwankert and his team solved what was an enduring mystery – the identity and fate of Titanic’s six Chinese survivors.

In the more than twenty-five years since Titanic was released, we’ve learned much more about the great ship, its remains and, especially, its passengers. The Six is an important story, especially now. It shows us the suffering and perseverance of a group of men who ended up on history’s most famous ship. It takes us beyond that fateful night and demonstrates that for the determined and courageous – like these six Chinese men – even a great shipwreck didn’t drown their dreams or sink their ambition.

James Cameron

New Zealand, January 2025

Notes on Measurements and Romanisation

Doing a proper deep dive into Titanic history is not unlike biblical archaeology. To produce original research based on fact, rather than a remixed regurgitation of legend and myth, one must put on cotton gloves; get out a pair of tongs; and, word by word, line by line, extract what is factual from any number of suspect eyewitness statements, newspaper interviews, media conjecture and outright lies.

The hulk of the Titanic story as we currently know it is encrusted in the rust and barnacles of hearsay and history. As such, we must chisel away numerous layers of impacted half-truths and nonsense to expose the bare metal that is the facts of Titanic’s sinking and the survival of the Chinese passengers aboard it.

To do this, I begin with the premise that the testimony given at both official inquiries into the sinking – the United States Senate Inquiry and the British Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry – forms the bedrock of the factual case regarding Titanic’s loss. We know that this testimony is, in places, flawed or inaccurate and that will be addressed or considered on an individual basis. It is also, of course, incomplete, because several main figures in the Titanic story, including Captain Edward Smith, Chief Officer Henry Wilde and First Officer William Murdoch, went down with the ship. However, it does form the official record and, as such, it gives us the ability to consider the primary question regarding each person’s testimony or account: could the person have been chronologically and physically present to witness the circumstances he or she is describing?

Beyond the testimony, there are statements that individuals made to the press, either close to the time of the sinking or later in life, perhaps in personal letters. The same standard applies: could the individual have seen what they claim to have seen, or are they merely repeating things they heard or read elsewhere?

Some researchers take every person’s statement at face value: where they were, when they were there and what they saw. That is at minimum naïve and at worst borders on reckless disregard for the truth in a story strewn with conjecture and genuine misinformation. The approach chosen for this book is to place known and verifiable facts at its centre so that accurate conclusions may be drawn from new and existing research.

Chinese Names

For the historian and storyteller, China from 1912 and throughout the twentieth century is a rich canvas upon which to work, with plenty of conflict, revolution and upheaval to twist the lives of that country’s people, leaving their stories for us to untangle today. This early-century chaos has left us with two established Romanisation systems for Mandarin Chinese words rendered in English, and a whole lot of approximations of other dialects, including Cantonese and Toisan, handed down to us without enforced standardisation. At the heart of this story are the names of eight Chinese passengers who sailed aboard Titanic, and even after years of research, we still don’t know exactly the origin of those Romanised names.

To minimise the confusion the contemporary reader (and this writer) will encounter, all place names are rendered as they would be pronounced today in Mandarin (except Hong Kong, which shall remain as is), using the Hanyu Pinyin system, which gives us spellings including Beijing and Taishan. ‘Toisan’ will be used to refer to the dialect spoken in Taishan and Taishan will refer to that area of Guangdong province. All given names will be rendered as they appear on official documents at the time, including immigration forms, shipping records and White Star Line tickets. This choice is made only for simplification of the text – it implies no political allegiance or fondness.

Chinese characters used in the text are traditional. The Chinese Titanic passengers would have used traditional characters, and so again it is an editorial choice for consistency.

As is Chinese custom, a person’s surname appears first, with any given names appearing after that. For example, Lee Bing’s family name is Lee, not Bing. He would be Mr Lee.

Measurements and weights will be presented in both the metric and imperial systems unless quoting from documents that specify only one.

Introduction

Finding the story of eight Chinese passengers of the RMS Titanic was akin to panning for gold, only to find a river of diamonds. I never expected there were any major new stories of the world’s most heavily researched maritime disaster to be found.

My own journey began with a completely different maritime disaster. In 2013, I began researching a Chinese ship that sank in 1948, claiming more than 2,000 lives. Originally, the intent was to tell the tale of China’s biggest maritime disaster, which had been almost completely forgotten, despite happening in the middle of the twentieth century. Its massive loss of life and the mysterious circumstances surrounding its sinking made it a story that I felt needed to be told. In preparing to present that story for the first time to an English-language audience and seeking the best way to contextualise the scale of that disaster for an audience outside China, I thought that the only comparable circumstance that readers would readily understand would be Titanic.

My research and interviews with survivors of the Chinese shipwreck progressed. I went back to my shelf of Titanic books, including classics such as Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember, checking the countless pages of voluminous research now available online – and that’s when the work suddenly shifted course.

I knew there had been Chinese passengers aboard Titanic; it’s the kind of detail that I noticed after spending almost my entire working life – more than twenty years – in China. But there was scant detail on the eight men, six of whom survived, and I wasn’t working on anything Titanic-related at the time. Besides, what more could be discovered about Titanic? The wreck was found more than thirty years ago, all the survivors are now dead and James Cameron’s film has set the story in cinematic stone. I bookmarked a page referencing the Chinese passengers and continued with my research.

As someone who lies in bed, stares at the ceiling and ponders questions about shipwrecks, I found my contemplations shift from pondering the unsolved mystery of a Chinese ship, and instead I started to obsess about the Chinese passengers. Who were they? Why were they on Titanic? Why did such a high percentage of the group survive? What happened to them after they reached New York?

I got to work on this project – this book and a documentary, also called The Six – with my creative partner Arthur Jones, a British documentary filmmaker based in Shanghai. As our research progressed, we began to think of the group of Chinese passengers as characters akin to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Third-Class passengers and workers who went on to live largely successful lives overseas, they may have been minor characters in the history of the twentieth century, but their respective stories would surface at opportune moments of major significance and shine an important light on both the major players and the wider story.

The story of The Six brings to the fore various factors that determined the course of the Chinese experience in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the waves of migrant labourers coming primarily from southern China; the overthrow of the imperial system in China with the Xinhai Revolution, shortly before Titanic’s launch and loss, and its resulting street-level social impact; the US Chinese Exclusion Act and similar anti-Chinese immigration laws in Canada and the United Kingdom; and the integration of Chinese immigrants into communities around the world by both the survivors of the shipwreck and their descendants.

This book seeks to answer many questions and raise many more. Were they heroes? Were they cowards? Or were they just lucky? What happened to the six survivors after they reached New York? Why did they seemingly disappear from history? And could one of the two Chinese passengers who perished at sea be buried in a Titanic cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia?

For the first time, The Six allows the Chinese passengers’ part of Titanic’s story to be told meaningfully. Until now, they have languished in infamy, have been derided as stowaways and were largely airbrushed out of the famous shipwreck’s story. Now, these men may finally gain their rightful place in Titanic history, more than a century after that memorable night.

Steven Schwankert

New Jersey, June 2024

Section I

1

A Piece of Wood

The man took a deep breath and pushed off as the ground disappeared below him. By stepping into the water, he was attempting to save his own life. Instead, he felt like he was choosing a certain death.

Frigid water punched him in the stomach and forced almost all the carefully drawn breath out of him. On his hands and neck, the salty liquid felt like it was stabbing him with thousands of tiny needles, each trying to burrow and draw out any heat remaining in his body. Slowly, it seeped through the layers of cotton and wool that had protected him for hours on the cold night. The shirts, jacket and coat worked in the air, but against water they were almost powerless.

The screams of the dying surrounded him. There were female voices and male voices. Not long before, some of these gentlemen had gallantly put their families in boats and stepped back, seemingly accepting their fate. Now the same men cried out for anyone to save them, their evening clothes not protecting them against the cold. Women wailed for someone to save their children. The new-moon night covered them in darkness from the moment the ship’s lights went out for the last time. In the lifeboats nearby, the ones who had benefited from the gentlemen’s acts of selflessness kept their distance, afraid that the unfortunates in the water would swamp them if they returned to assist.

He remembered when he had first swum off the island where he grew up, a forgotten refuge for the survivors of a dynasty that Kublai Khan had crushed 800 years before. There, the water was clear and warm. Now he swam through black and cold water, looking for a lifeboat, looking for something – anything.

In just a few minutes, he had gone mostly numb, feeling the temperature only on his neck and shoulders, where the air made the water feel even colder. The man did his best to keep his head above the surface, but as each minute passed, his mouth and nose went under more and more. The life jacket helped to counter the weight of his saturated clothes, but the drag made every stroke more difficult.

He didn’t know where the others were. Did they get off? Were they in the water too? He thought some of them had made it into a lifeboat, but wasn’t sure, distracted by his predicament. He had waited on deck for a boat, but the crew could not get it ready in time. The water came up before the boat could launch, so he chose to swim rather than sink. It will pull me under, he thought, but the rush of air he heard behind never became the suction he feared. Despite years of working as a sailor, this was his first shipwreck. For the moment, at least, he was alive.

Many were already incapacitated or dead. The man swam among them, each body providing a morbid moment of added buoyancy. He wondered whether he should just grab onto one and use the dead to save his own life, but he moved on. Keep swimming, he thought. Keep swimming, or you’ll end up like them.

But it was becoming a struggle. The ocean was barely above freezing, the air only slightly warmer. Somewhere out there was a mountain of frozen water, a black island in the middle of the Atlantic that had ripped the ship open and begun its slow but inevitable death.

The noise around him began to subside. The cold had claimed some; others just gave up. Most audible was his gurgling and spouting that accompanied every breath. He had to push himself up to breathe on almost every stroke now. He could not hear or see any boats nearby.

Suddenly, his hand hit something solid. It did not disappear under the water when he pushed on it. He slapped at it. It was big and thick. He raised his other hand to touch it. It felt like a door or maybe a table. The man pulled himself on top of it and pushed the object underneath him. He could just barely get out of the water. He almost toppled back in as it shifted, but he balanced himself. There were no waves to jostle him but to make sure he didn’t slide off, the man undid his belt and lashed himself to the object as best he could. The cold had made him feel drunk, commands emerging from his brain but travelling too slowly to his arms and fingers.

It was quiet now. The ocean made no noise, and those in the water were still. There was no light except the stars – so many of them, but so dim. The air was cold, but not like the water had been, at least, it didn’t feel that way. The ship didn’t get me and the water didn’t get me, but I will die here anyway tonight, he thought.

Then there was a flash, not a bright one, but a light from somewhere. It flashed again. The light was moving back and forth, and it seemed to be getting slowly closer. Someone was yelling out in English. The man tried to say, ‘Here! Here!’ in English, but he could not. He could barely move.

The light was on a boat with a few men aboard it. It was coming closer.

‘Here! Here!’

The men on the boat could not hear him but they were approaching him. The light fell upon him, and the man moved, tried to reach out to them, but could not lift his arm.

‘Here! Here!’

The officer on the boat shouted and pointed the light toward the man floating on a piece of wood. The officer and mate reached down and lifted the man out of the water, almost a dead weight, wrapped in cold, soaked clothes. The rescued man – who appeared to the officer to be Chinese, or maybe Filipino – thanked the seamen again and again, although he wasn’t sure if he was forming the words.

The boat continued searching, the officer calling out and shining the light, but no one else was found alive. Two others had been rescued before the man was pulled from the water. One of them, a portly First-Class passenger, had died.

A few hours later, as dawn broke, a big ship began to approach the constellation of lifeboats spread out across the surface of the water. Slowly, the boats made their way alongside the larger vessel, the man catching sight of its name – Carpathia. Still cold, still exhausted, at least now his limbs functioned properly when he had to reach up and grab the rope net that served as a ladder onto the rescue ship.

Aboard Carpathia, he found his compatriots. But not all of them were there.

Years later, in a letter home to family, he recalled the night in a poem:

The sky is high, the waves come rolling by

A piece of wood saves my life

I see my brothers, three or four

The tears roll down as I laugh1

2

The World in 1912

In 1912, humankind was on the move, building bigger machines and pushing them to the horizon. Many people – mostly men – were searching for work for the first time, not just over the hill but across oceans, farther from their homes than they had ever imagined.

When workers in Northern Ireland hammered the first rivet into place on the steel hulk that would become RMS Titanic, railways and steamships had already existed for decades, but as the new century began, people began demanding superlatives in their travel: bigger, further, faster. At the start of the twentieth century, humans were finally reaching the furthest points on the globe. In 1909, American Robert Peary and his team became the first known humans to stand on the geographic North Pole, while Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and his expedition arrived at the South Pole in December 1911. Although climbers had reached the top of the highest mountains in Africa and South America at the end of the nineteenth century, summiting the world’s highest peaks in the Himalayas and the Karakorum were decades away. Slowly, surely, the world was becoming a smaller, or at least more accessible, place.

In the air, as early as 1875, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin had been fooling around with designs for airships that combined a giant balloon filled with hydrogen and a gondola that could be attached to carry pilots and a navigation assembly, along with cargo, passengers and weapons. On 24 April 1912, the Imperial German Navy ordered its first Zeppelin for military use. But airships remained in their nascent stage and the idea of using them for a transatlantic passenger service was no closer than space travel.

Two brothers in the United States, Orville and Wilbur Wright, made their first successful aeroplane flights in 1903. But almost a decade later, humans were not measurably closer to flying in them from one continent to another. Like airships, militaries eyed aeroplanes for use in reconnaissance or aerial bombardment, but not for the large-scale transport of people or machines.

Wealthy people began to buy automobiles for recreation and local transportation but, although their popularity was growing, the Ford Motor Co. didn’t open its first assembly line to build cars until 1913. However, the slow adoption of the automobile initiated a transformation that would last throughout the rest of the century.

Although no country was even close to being 50 per cent connected, electrification was altering the landscape in large cities around the world and starting to creep out toward more rural areas. Cities like London, New York and Shanghai all had electric streetlights before 1900, but delivering power to dense urban populations was easier and less expensive than stretching kilometres of new power lines to serve fewer customers. The construction of new improved roads suitable for automobiles also paved the way for power lines to be installed alongside them.

In the first years of the twentieth century, coal powered the world. It heated homes, powered factories and provided the fuel that pushed trains down the track and great ships across the oceans. They may have been called steamships, but coal fires generated all the necessary steam. When the White Star Line’s passenger ship Olympic made its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York in 1910, it used about 3,500 tons of the black stuff, averaging a speed of 21.7 knots (about 40kmh/25mph). Oil as a potential fuel source was discovered in quantity in 1875 but remained a decade or so away from widespread exploitation and use.

With aircraft and automobiles not yet viable, to cover significant distances by land, one boarded a train. Massive rail networks already stretched across North America, parts of Europe, India and from Moscow to Manchuria. If a person wanted to cross an ocean in 1912, one bought a ticket on a regularly scheduled voyage, preferably aboard the swiftest ship one could afford.

The tallest building in the world, the Woolworth Building at 233 Broadway in New York, was in the final stages of completion, reaching 792ft (241.4m). It would hold that title for eighteen years.

Mass communications and media came mostly from the printed word, namely books and large-circulation newspapers. The year’s bestsellers show English-language readers’ interest in their wider world – or at least, fanciful, fictionalised versions of it. Arthur Conan Doyle, best known as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, sold bushels of The Lost World, about an expedition to the Amazon that discovers prehistoric animals, including dinosaurs – a Jurassic Park before there was Jurassic Park. Swinging out of the trees came Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes, a human raised by non-human primates in an African jungle.

Silent films were becoming popular. Films at the time were fifteen to twenty minutes in length, with title cards instead of recorded dialogue, and were often accompanied by a live organist or orchestra in the cinema. Directors like D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett directed multiple films per year, and early performers like brothers John and Lionel Barrymore, sisters Lillian and Dorothy Gish, and Mary Pickford became known to the public.

The technology to record and play music existed, but a phonograph or early Victrola player was still out of the financial reach of the average person. People enjoyed playing music at home. Live music and theatrical performances were well established and popular, especially in cities, along with touring musicians and circuses that would visit more far-flung areas.

Sports leagues in Europe and North America were starting to take shape. In the United States, sixteen teams, all in cities east of the Mississippi River, opened the Major League Baseball season. The Boston Red Sox began 1912 on the road against the New York Highlanders. The visitors looked forward to inaugurating their new home stadium, Fenway Park, on 20 April. Later that year, American university teams would play the first season of modern college football, with new rules, including four downs, or attempts to gain 10 yards, awarding 6 points for a touchdown score instead of 5 and shortening the field to 100 yards in length – rules that remain in force today, both in college and professional American football.

In the United Kingdom, Blackburn Rovers won their first English Football League title. Then, as now, twenty teams in the top division played thirty-eight matches, with Blackburn finishing above their nearest rival, Everton. Preston North End and Bury were relegated. In cricket, England retained the Ashes and won the sole instalment of a competition called the Triangular Tournament on home ground, defeating the only other two test nations at the time – Ashes rival Australia and third opponent South Africa.

Stockholm, Sweden, hosted the 1912 Summer Olympics from 6–22 July, with twenty-eight nations, almost all from North America and Europe, along with Australasia (a combined Australia and New Zealand team); Chile; Egypt; South Africa; Turkey; and, in the first Olympic appearance by an Asian nation, Japan. Native American athlete Jim Thorpe won the gold medal in the modern pentathlon and the decathlon, two of the United States’ twenty-six golds, the most won by any single country. Hosts Sweden led the total medal count with sixty-five.

Europe and Africa

As of April 1912, the United Kingdom already had its third monarch of the new century. King George V, a grandson of Queen Victoria, had been on the throne for fewer than two years, following the death of his father, King Edward VII. Only a few months earlier, George V became the first and only British monarch to attend his imperial durbar in India. Herbert Henry Asquith of the Liberal Party served as His Majesty’s Prime Minister. Britain remained the world’s greatest power, ruling from the world’s largest city, London, with the sun always shining upon the Union Jack somewhere.

Europe was enjoying an extended period of peace, but the undercurrents of revolution and war were already coursing through the continent. In Vienna, an aspiring artist named Adolf Hitler made a living as a day labourer and on the side, sold his watercolour paintings of city landmarks – paintings that seldom included any depictions of his fellow Viennese, or any other people, for that matter. In between making mediocre art and other odd jobs, he first began to consume antisemitic literature and form his diabolical ideas about the Jews and where he thought they belonged in European society.

An established Russian political revolutionary, Vladimir Lenin, had taken up residence in Paris and seized upon the works of dead German economist and philosopher Karl Marx. In January 1912, Lenin and his followers broke away from other Russian socialists and formed an organisation that would later become colloquially known as the Bolsheviks.

In South Africa, an Indian lawyer and activist named Mohandas Gandhi had begun advocating non-violent resistance to racist policies there, founding a utopian community called Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg.

North America

The increasing wealth, industrial output and military might of the United States had grown during the nineteenth century, and waves of immigration there continued. The year began with forty-six states and ended with forty-eight. New Mexico became the forty-seventh state on 6 January, with Arizona finally joining on 14 February to realise Manifest Destiny, a political and military philosophy that expanded the growing country from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. That year, the Governor of New Jersey, Democrat Woodrow Wilson, and incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft campaigned against each other in the election for US President. Former President Theodore Roosevelt would join the race later in the year, after failing to win the Republican Party’s nomination.

One of the world’s wealthiest people, and one of its most famous in 1912, was an American. John Jacob Astor IV was his family’s youngest child and only son, born in 1864 in New York. On his way to greater renown and riches, Astor found success writing a science fiction novel, A Journey in Other Worlds, before financing and serving in his own unit during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Eventually, he began investing in real estate and built the Astoria Hotel, abutting a similar building that had been constructed by a rival cousin, William Waldorf Astor, called the Waldorf Hotel.

Astor was an avid sailor and enjoyed taking his yacht Nourmahal along the American coast and to the Caribbean. He lent the boat to the US Navy during the Spanish-American War. Despite his apparent love for the sea, Astor did not have much luck while on it. A mishap in September 1893 led to him beaching the yacht on a bank of the Hudson River and made the front page of The New York Times.1

In a separate incident, Astor set sail aboard Nourmahal on 5 November 1909 from Port Antonio, on Jamaica’s north-east coast, but then went missing for more than two weeks. The captain of a cargo ship, SS Annetta, claimed he spotted the 250ft (76.2m) yacht on about 14 November, near the island of San Salvador. A hurricane swept through the area and the disappearance led many in the press and New York society to fear the worst.

Astor eventually arrived in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 21 November, unaffected by the storm. Ultimately, the facts disproved Annetta’s sighting: to be in San Salvador on 14 November would have put Astor’s yacht about 250 miles (400km) off course, more than the distance between Port Antonio and San Juan.

Asia

In Thailand, Vajiravudh, also known as King Rama VI, survived an attempted coup to retain absolute rule. In Japan, Emperor Mutsuhito, later known as Emperor Meiji, was nearing the end of his reign and the period of reform he championed. Following his death in July, Emperor Taisho assumed the throne. At the time, Japan controlled large parts of China, including the Liaodong Peninsula (now mostly Liaoning Province) and the island of Taiwan. Japan had officially colonised Korea in 1910 and remained in control of the Korean Peninsula.

During the second half of 1911, Outer Mongolia seized upon the crumbling authority of China’s Qing Dynasty and shook off Chinese rule, with tacit approval from Russia, forming the Bogd Khanate of Mongolia.

No country in the world saw more turmoil in 1912 than China. In October 1911, the Xinhai Revolution began as a military uprising in the central city of Wuhan, then caught fire across the country, ending millennia of imperial rule and declaring the brittle Republic of China (ROC) on 1 January. For the first time in 5,000 years, China’s people would be ruled by someone other than an emperor – and by a government that was not absolute. The Qing Dynasty had failed to fend off foreign incursions and interference from all directions, and the nation’s people had suffered from internal rebellions and natural disasters that made their lives unbearable. While China attempted to move away from its imperial past, events and economic conditions that had been initiated decades earlier continued to influence the hundreds of thousands of Chinese who had already begun to leave the country to find work elsewhere.

3

From the Four Counties to the World

We know little about the early life of a man who travelled across the world, took on many names, worked a variety of jobs, spent thirty-five years in the United States as an undocumented migrant, and survived the world’s most famous shipwreck along the way. But we know that Fong Wing Sun (方榮山) could swim, and we imagine that as a boy he paddled through the warm, clear water of the South China Sea that surrounded his island home.1 Perhaps he thought for a moment that he was swimming like one of the ducks that his family raised in a nearby pond. Maybe we can bring the ducks down here to the saltwater next time and we can swim together, he thought. He turned and swam back to where his father was standing, knowing it was time to go home.

Xiachuan Island was probably not where the remaining members of the Southern Song Dynasty court (1127–1279) expected they would end up. Most likely, they had never even heard of it until their wet feet first stepped upon its sands. But it seemed like the perfect hiding place for people fleeing the armies of Kublai Khan: it was a beyond-the-horizon island that was out of sight, and hopefully out of the minds, of people who wanted to kill them.

Xiachuan was far from unknown. Mariners used it as a navigational landmark, turning south from there to head toward South East Asia. Not all were so lucky; hundreds of shipwrecks fill the waters around it and its larger neighbouring Shangchuan Island, including the South China Sea No. 1 treasure ship, which was discovered in 1983. But it probably wasn’t any better known to the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) than it was to the former Song leaders. They found safety there.

Centuries later, the island’s long-time inhabitants still see themselves as the Song survivors. The Chinese they speak is mutually unintelligible with today’s standard Mandarin – they are more likely to find someone in New York or Vancouver’s Chinatown who will understand them than they are in Beijing.

A few years into the twentieth century, several dozen kilometres from that island and back on the mainland, a teenager knew that his time at what he called home would soon be coming to an end. Growing up in Hengtang village (横糖村), Lee Bing (李炳) faced the same pressures that other young men in Taishan faced: no path to the family’s property and few, if any, employment opportunities locally. Like so many other men from the Taishan (台山) region before him, Lee Bing’s future likely lay elsewhere. The year 1912 had seen massive political upheaval in China as the revolution threw off thousands of years of imperial system, but economic forces at work in southern China and elsewhere were already narrowing the future choices for men born in Taishan at the end of the nineteenth century.

For the Chinese men who would later travel on Titanic, at least two, Fong Wing Sun and Lee Bing, were known to be from different parts of Taishan, and it is likely that more – or perhaps even all eight – came from there. The families they loved and sought to support would benefit from their labour without the pleasure of their company. Regular remittances would make life for those who stayed behind easier. In some cases, the overseas sons even built houses in their home villages.

While still under the guise of a temporary departure, at least half of these men left Taishan permanently. They carried their language and customs across the world with them, the way that all expatriates do, but many of them never returned.

The boy walked down the main street carrying his books. It wasn’t far from school to his home, only a few minutes away – a round trip he made twice a day. School in the morning, back home for lunch, return to school, then home at the end of the day. Sometimes, when it rained hard, his mother made a small lunch for him to eat and he stayed at school for the whole day. Trees shaded much of the walk, which was a relief during the hot months of the year. The school had been built by Christian missionaries, but his teachers were all from their village.

Little Fong Wing Sun liked studying, and particularly he liked writing, both in Chinese and the little bit of English that he was learning. His letters were boxy – all straight lines and right-angle turns, no curves.

The Fong family’s village was on some of the best land on Xiachuan Island. Away from both the coast and the island’s high hills, they were protected from flooding and landslides. The Fong house was a simple one, with two and a half rooms: one for sleeping, one for general living and food preparation and then a small kitchen area for cooking. His father kept talking about adding some space on top of the house, but it hadn’t happened yet.

When he came home from school, Wing Sun put down his books and swept the floor as he was told to do every day. He then tried to finish any school assignments he had before it got too dark to read outside. Working by candlelight was hard on his eyes and it made him tired. Every night his father told him and his brothers and sister to go to sleep, and if Wing Sun was lucky, his father’s snoring didn’t wake him up.

Wing Sun wondered about the future. Even with his schooling, what would he be able to do? Be a farmer like his father? He read about China’s great ancient armies, but to him, his island was China, was the world. Could he travel to Guangzhou someday, even to Beijing where the emperor lived?

The next day, as he walked to school, Wing Sun couldn’t stop thinking about the rest of the world. Did it really exist, or was it just a story, like the other stories in his books? Would he ever get to see any of it?

Taishan Today

If you visit Taishan today, you could be forgiven for failing to recognise it as one of the epicentres of the Chinese diaspora. Called ‘Toisan’ or ‘Hoisan’ in the local dialect, and not to be confused with the sacred mountain in Shandong Province of the same name and Romanised spelling, the area in central southern Guangdong Province includes what is referred to as the ‘si yi’ in Mandarin or ‘sei yap’ locally, both meaning ‘the four counties’, namely Enping (locally pronounced Yanping), Kaiping (Hoiping), Taishan (Toisan) and Xinhui (Sunwui). Politically, the area was subsumed into Jiangmen Prefecture in 1951.

Taishan natives are quick to point out that this relatively recent reorganisation used to be the other way around. Given this realignment, the area may now also be referred to as the Five Counties. In 2022, Jiangmen Prefecture had a population of about 4.8 million and a size of almost 9,500 square km (3,668 square miles), with Jiangmen as its largest city.2

Kaiping remains a popular tourist destination today, thanks to the presence of the distinctive diaolou, several fortified structures built at the end of the nineteenth century to provide families with protection against armed bandits that occasionally raided the area. The city of Taishan features several pedestrian streets containing homes and storefronts, all built with money provided by those who had emigrated overseas and wanted to demonstrate their gratitude for the support and well-being of relatives back home.

As of 2021, the population of the Four Counties stands at about 1 million, with most of those residents still classified as rural. Notably, no airport serves Taishan directly; visitors from parts of China or overseas usually fly into Zhuhai, just north of Macau, then proceed by bus or car for about ninety minutes to two hours. The smaller Guangdong city of Foshan also has an airport 55km from Jiangmen, which is more often used by domestic travellers. A regional rail service takes passengers to and from Guangzhou or Zhanjiang on the coast. The area is also accessible via a series of highways.

Enjoying a subtropical climate, today the area looks fertile and prosperous, although not as much as other parts of Guangdong further east, specifically the cities part of the Pearl River Delta that form a halo around Hong Kong. Including late-twentieth-century boomtowns like Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Dongguan, it is those cities that became the heart of China’s initial economic growth engine after reform and opening in 1979. Although far from impoverished, central Taishan can’t compare to its eastern neighbours for neon and pure economic firepower; its average income is about half that of the residents of the Pearl River Delta cities.

Taishan became the initial centre for Chinese labour immigration because of both success and misfortune and also political geography. The Guangdong coastal area in general developed beyond a strictly agrarian economy more quickly than surrounding provinces. This saw the rise not only of increased agricultural productivity and the planting of cash crops, but also basic manufacturing of goods that required labour, included the growing of tobacco, the making of textiles and some mining. This kind of success is good for the economy, landlords and manufacturers, but not necessarily for large families – at least, not the younger sons of large families, who are reliant upon inheritance for their own future subsistence.

The Taishan area’s ports never developed as fully or quickly as those that were first used and later colonised by European imperial powers. Hong Kong and Macau already existed as major points for trade, and even today, the port of Taishan is dwarfed by those elsewhere in Hong Kong and Shenzhen. As such, the region never received the investment that flowed into neighbouring coastal cities, and its population did not move away from agriculture as a primary economic activity as quickly. Still, the foreign trade that developed along the coast began to act as a magnet for labour and had an impact on the economy of the rest of the province.

In the first half of the 1800s, despite a good climate and a plethora of arable land, a trio of plagues descended upon the area, each exacerbating the other. The first came in the form of military conflict with Western powers, namely France and the United Kingdom, known colloquially as the Opium Wars. Flaring up sporadically between 1839 and 1842, this series of engagements resulted in the ceding of Hong Kong Island to the UK, and the later ninety-nine-year leasing of the surrounding area, which is still referred to as the New Territories. It also opened Guangzhou as a port to foreign trade.

This conflict was the first in a series of disruptions afflicting Taishan. It might never have become an early source for emigrant labour from China, but combined with local Confucian tradition that saw the raising of large families as a duty and a sign of prosperity, a reduction in the amount of usable farmland meant that even a stable population was more than that area could support. Able-bodied sons are an asset when working tracts of land but when sons outnumbered acreage, a big family became a liability.

In 1843, Hong Xiuquan (洪秀全), a would-be civil servant originally from Guangdong, had a fever dream that led him to the conclusion that he was the brother of Jesus Christ and that his brother had commanded him to overthrow the ‘devils’ of the ruling Qing Dynasty. The Qing, who were ethnically Manchu from north-eastern China, were despised by many of the majority Han Chinese. That ethnic disparity provided fervour even for Taiping troops, who may not have shared Hong’s Christian faith.

Hong co-founded a quasi-Christian sect, the Society of God Worshippers,3 which was as much anti-Manchu as it was Christian. When some of Hong’s followers were arrested in Guangxi in 1850, it became an armed conflict and began a rebellion against the Qing Dynasty that would last for the next fourteen years. During this period, Hong and his followers, who took their name from the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom that they sought to establish, assembled a force of as many as 2 million troops, both infantry and cavalry, and killed an estimated 20–30 million soldiers and civilians – mostly the latter.

During this period, Qing Dynasty government services, such as they were at the time, were disrupted, and young men were sought for conscription into the Qing army. Additional taxes were levied on landowners to finance the war against the Taipings. While Guangdong itself was not a major battleground during the rebellion, the Qing government actively persecuted members of the Hakka, or ‘guest people’, minority there. Although ethnically Han Chinese, the Hakka are linguistically distinct, tracing their history to central China, from which point they migrated or were pushed south, perhaps as part of a political persecution dating back as far as 200 BC