Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: АСТ

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Great Books

- Sprache: Englisch

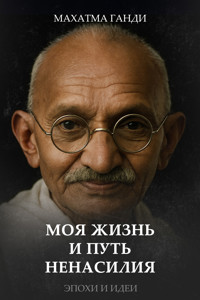

Махатма Ганди – индийский политический и общественный деятель, боровшийся за независимость Индии от Великобритании. Он известен своей философией ненасилия под названием сатьяграха, оказавшей большое влияние на движения сторонников мирных перемен. Автобиография Ганди «Моя жизнь» рассказывает о его становлении и духовных исканиях, а также о борьбе за права в Южной Африке и об освобождении Индии. Кроме нее в данную книгу вошли другие произведения Ганди на политические и социальные темы. Читая эту книгу Вы сможете не только узнать больше о жизни и идеях Махатмы Ганди, но и попрактиковать свой английский.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 612

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Махатма Карамчанд Ганди The Story of My Life / История моей жизни

© Оформление. ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2024

The Story of My Life

Introduction

It is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography or story of my life. I simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but those experiments, the story will take the shape of an autobiography. My experiments in the political field are now known. But I should certainly like to narrate my experiments in the spiritual field which are known only to myself, and from which I have derived such power as I possess for working in the political field. The experiments I am about to relate are spiritual, or rather moral; for the essence of religion is morality.

Only those matters of religion that can be understood as much by children as by older people, will be included in this story. If I can narrate them in a dispassionate and humble spirit many other experiments will… obtain from them help in their onward march.

M. K. Gandhi

The Ashram, Sabarmati

Part I: Childhood and youth

1. Birth and Parentage

My father, Karamchand Gandhi, was Prime Minister in Porbandar. He was a lover of his clan, truthful, brave and generous, but short-tempered.

He never had any ambition to accumulate riches and left us very little property.

He had no education. At best, he might be said to have read up to the fifth Gujarati standard. Of history and geography he was innocent. But his rich experience of practical affairs stood him in good stead in the solution of the most intricate questions and in managing hundreds of men. Of religious training he had very little, but he had that kind of religious culture which frequent visits to temples and listening to religious discourses make available to many Hindus.

The outstanding impression my mother has left on my memory is that of saintliness. She was deeply religious. She would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers. Going to Haveli – the Vaishnava temple – was one of her daily duties. As far as my memory can go back, I do not remember her having ever missed the Chaturmas. She would take the hardest vows and keep them whatever happened. Illness was no excuse for relaxing them. I can recall her once falling ill when she was observing the Chandrayana vow, but the illness was not allowed to come in the way of the observance. To keep two or three fasts one after another was nothing to her. Living on one meal a day during Chaturmas was a habit with her. Not content with that she fasted every other day during one Chaturmas. During another Chaturmas she vowed not to have food without seeing the sun. We children on those days would stand, staring at the sky, waiting to announce the appearance of the sun to our mother. Everyone knows that at the height of the rainy season the sun often does not show his face. And I remember days when, at his sudden appearance, we would rush and announce it to her. She would run out to see with her own eyes, but by that time the sun would be gone, thus depriving her of her meal. “That does not matter,” she would say cheerfully, “God did not want me to eat today.” And then she would return to her round of duties.

My mother had strong common sense. She was well informed about all matters of State.

Of these parents I was born at Porbandar, otherwise known as Sudamapuri, on the 2nd October 1869.

2. At School

I passed my childhood in Porbandar. I remember having been put to school. It was with some difficulty that I got through the multiplication tables. I recollect nothing more of those days than having learnt, in company with other boys, to call our teacher all kinds of names.

I must have been about seven when my father left Porbandar for Rajkot. There I was put into a primary school, and I can well remember those days. As at Porbandar, so here, there is hardly anything to note about my studies.

From this school I went to the suburban school and thence to the high school, having already reached my twelfth year. I do not remember having ever told a lie, during this short period, either to my teachers or to my schoolmates. I used to be very shy and avoided all company. My books and my lessons were my sole companions. To be at school at the stroke of the hour and to run back home as soon as the school closed, that was my daily habit. I literally ran back, because I could not bear to talk to anybody. I was even afraid lest anyone should poke fun at me.

There is an incident which occurred at the examination during my first year at the high school and which is worth recording. Mr. Giles, the Educational Inspector, had come on a visit of inspection. He had set us five words to write as a spelling exercise. One of the words was 'kettle'. I had misspell it. The teacher tried to prompt me with the point of his boot, but I would not be prompted. It was beyond me to see that he wanted me to copy the spelling from my neighbour's slate, for I had thought that the teacher was there to super- vise us against copying. The result was that all the boys, except myself, were found to have spelt every word correctly. Only I had been stupid. The teacher tried later to tell me that I should not have been so stupid, but without effect. I never could learn the art of 'copying'.

Yet the incident did not in the least lessen my respect for my teacher. I was, by nature, blind to the faults of elders. Later I came to know of many other failings of this teacher, but my regard for him remained the same. For I had learnt to carry out the orders of elders, not to look critically at their actions.

Two other incidents belonging to the same period have always clung to my memory. As a rule I did not like any reading beyond my school books. The daily lessons had to be done, because I did not want to be taken to task by my teacher, nor to deceive him. Therefore, I would do the lessons, but often without my mind in them. Thus when even the lessons could not be done properly, there was of course no question of any extra reading. But somehow my eyes fell on a book purchased by my father. It was Shravana Pitribhakti Nataka (a play about Shravana's devotion to his parents). I read it with intense interest. There came to our place about the same time wandering showmen. One of the pictures I was shown was of Shravana carrying, by means of slings fitted for his shoulders, his blind parents on a pilgrimage. The book and the picture left a permanent impression on my mind. “Here is an example for you to copy,” I said to myself.

Just about this time, I had se- cured my father's permission to see a play performed by a certain dramatic company. This play – Harishchandra+ captured my heart. I could never be tired of seeing it. But how often should I be permitted to go? I kept thinking about it all the time and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number. “Why should not all be truthful like Harishchandra?” was the question I asked myself day and night. To follow truth and to go through all the ordeals Harishchandra went through was the one ideal it inspired in me. I literally believed in the story of Harishchandra. The thought of it all often made me weep.

I was not regarded as a dunce at the high school. I always enjoyed the affection of my teachers. Certificates of progress and character used to be sent to the parents every year. I never had a bad certificate. In fact I even won prizes after I passed out of the second standard. In the fifth and sixth I obtained scholarships of rupees four and ten respectively, an achievement for which I have to thank good luck more than my merit. For the scholarships were not open to all, but reserved for the best boys amongst those coming from the Sorath Division of Kathiawad. And in those days there could not have been many boys from Sorath in a class of forty to fifty.

My own recollection is that I had not any high regard for my ability. I used to be astonished whenever I won prizes and scholarships. But I very jealously guarded my character. The least little fault drew tears from my eyes. When I merited, or seemed to the teacher to merit, a rebuke, it was unbearable for me. I remember having once received a beating. I did not so much mind the punishment, as the fact that it was considered my deserts. I wept piteously. That was when I was in the first or second standard. There was another such incident during the time when I was in the seventh standard. Dorabji Edulji Gimi was the headmaster then. He was popular among boys, as he was a disciplinarian, a man of method and a good teacher. He had made gymnastics and cricket compulsory for boys of the upper standards. I disliked both. I never took part in any exercise, cricket or football, before they were made compulsory. My shyness was one of the reasons for this aloofness, which I now see was wrong. I then had the false notion that gymnastics had nothing to do with education.

I may mention, however, that I was none the worse for keeping away from exercise. That was because I had read in books about the benefits of long walks in the open air, and having liked the advice, I had formed a habit of taking walks, which has still remained with me. These walks gave me a fairly hardy constitution.

The reason of my dislike for gymnastics was my keen desire to serve as nurse to my father. As soon as the school closed, I would hurry home and begin serving him. Compulsory exercise came directly in the way of this service. I requested Mr. Gimi to exempt me from gymnastics so that I might be free to serve my father. But he would not listen to me. Now it so happened that one Saturday, when we had school in the morning, I had to go from home to the school for gymnastics at 4 o'clock in the afternoon. I had no watch, and the clouds deceived me. Before I reached the school the boys had all left. The next day Mr. Gimi, examining the roll, found me marked absent. Being asked the reason for absence, I told him what had happened. He refused to believe me and ordered me to pay a fine of one or two annas (I cannot now recall how much).

I was convicted of lying! That deeply pained me. How was I to prove my innocence? There was no way. I cried in deep anguish. I saw that a man of truth must also be a man of care. This was the first and last instance of my carelessness in school. I have a faint recollection that I finally succeeded in getting the fine refunded. The exemption from exercise was of course obtained, as my father wrote himself to the headmaster saying that he wanted me at home after school.

But though I was none the worse for having neglected exercise, I am still paying the penalty of another neglect. I do not know whence I got the notion that good handwriting was not a necessary part of education, but I retained it until I went to England. Bad handwriting should be regarded as a sign of an imperfect education. I tried later to improve mine, but it was too late. I could never repair the neglect of my youth.

Two more incidents of my school days are worth recording. I had lost one year because of my marriage, and the teacher wanted me to make good the loss by skipping the class – a privilege usually allowed to hard-working boys. I therefore had only six months in the third standard and was promoted to the fourth after the examinations which are followed by the summer vacation. Most subjects were taught in English from the fourth standard. I found it very hard. Geometry was a new subject in which I was not particularly strong, and the English medium made it still more difficult for me. The teacher taught the subject very well but I could not follow him. Often I would lose heart and think of going back to the third standard, feeling that the packing of two years' studies into a single year was too much. But this would discredit not only me, but also the teacher; because, counting on my ability, he had recommended my promotion. So the fear of the double discredit kept me at my post. When, however, with much effort I reached the thirteenth proposition of Euclid, the utter simplicity of the subject became clear to me. A subject which only required a pure and simple use of one's reasoning powers could not be difficult. Ever since that time geometry has been both easy and interesting for me.

Sanskrit, however, proved a harder task. In geometry there was nothing to memorize, whereas in Sanskrit, I thought, everything had to be learnt by heart. This subject also began from the fourth standard. As soon as I entered the sixth I became disheartened. The teacher was a hard task-master, anxious, as I thought, to force the boys. There was a sort of rivalry going on between the Sanskrit and the Persian teachers. The Persian teacher was lenient. The boys used to talk among themselves that Persian was very easy and the Persian teacher very good and considerate to the students. The 'easiness' tempted me and one day I sat in the Persian class. The Sanskrit teacher was grieved. He called me to his side and said: “How can you forget that you are the son of a Vaishnava father? Won't you learn the language of your own religion? If you have any difficulty, why not come to me? I want to teach you students Sanskrit to the best of my ability. As you proceed further, you will find in it things of great interest. You should not lose heart. Come and sit again in the Sanskrit class.”

This kindness put me to shame. I could not disregard my teacher's affection. If I had not acquired the little Sanskrit that I learnt then, I should have found it difficult to take any interest in our sacred books. In fact I am sorry now that I was not able to acquire a more thorough knowledge of the language, because I have since realized that every Hindu boy and girl should possess sound Sanskrit learning.

3. Marriage

It is my painful duty to have to record here my marriage at the age of thirteen. As I see the youngsters of the same age about me who are under my care, and think of my own marriage, I am inclined to pity myself and to congratulate them on having escaped my lot. I can see no moral argument in support of such early marriage.

I do not think it meant to me anything more than good clothes to wear, drum beating, marriage processions, rich dinners and a strange girl to play with. We gradually began to know each other, and to speak freely together. We were the same age. But I took no time in assuming the authority of a husband.

I would not allow my wife to go anywhere without my permission. And Kasturba was not the girl to put up with any such thing. She made it a point to go out whenever and wherever she liked. More restraint on my part resulted in more liberty being taken by her and in my getting more and more angry. Refusal to speak to one another thus became the order of the day with us, married children. I think it was quite innocent of Kasturba not to have bothered about my restrictions. How could an innocent girl put up with any restraint on going to the temple or on going on visits to friends? If I had the right to restrict her, had not she also a similar right? All this is clear to me today. But at that time I had to make good my authority as a husband!

Let not the reader think, however, that ours was a life of constant quarrels. For my severities were all based on love. I wanted to make my wife an ideal wife. My ambition was to make her live a pure life, learn what I learnt, and identify her life and thought with mine.

I do not think Kasturba had any such desire. She did not know to read or write. By nature she was simple, independent, persevering and, with me at least, shy. She was not impatient of her ignorance and I do not recollect my studies having ever made her want to go in for studies herself.

4. A Tragic Friendship

Amongst my few friends at the high school I had, at different times, two who might be called intimate. One of these friendships did not last long, though I never gave up my friend. He gave me up, because I made friends with the other. This latter friendship I regard as a tragedy in my life. It lasted long. I formed it in the spirit of a reformer.

This companion was originally my elder brother's friend. They were classmates. I knew his weaknesses, but I regarded him as a faithful friend. My mother, my eldest brother, and my wife warned me that I was in bad company. I was too proud to heed my wife's warning. But I dared not go against the opinion of my mother and my eldest brother. Nevertheless I pleaded with them saying, “I know he has the weakness you attribute to him but you do not know his virtues. He cannot lead me astray, as my association with him is meant to reform him. For I am sure that if he reforms his ways, he will be a splendid man. I beg you not to be anxious on my account.”

I do not think this satisfied them, but they accepted my explanation and let me go my way.

A wave of 'reform' was sweeping over Rajkot at the time when I first came across this friend. He informed me that many of our teachers were secretly taking meat and wine. He also named many well-known people of Rajkot as belonging to the same company. There were also, I was told, some highschool boys among them.

I was surprised and pained. I asked my friend the reason and he explained it thus: “We are a weak people because we do not eat meat. The English are able to rule over us, because they are meat-eaters. You know how hardy I am, and how great a runner too. It is because I am meat-eater. Meat-eaters eaters do not have boils, and even if they sometimes happen to have any, these heal quickly. Our teachers and other distinguished people who eat meat are no fools. They know its virtues. You should do likewise. There is nothing like trying. Try, and see what strength it gives.”

All these pleas on behalf of meat-eating were not made at a single sitting. They represent the substance of a long and elaborate argument which my friend was trying to impress upon me from time to time. My elder brother had already fallen. He therefore supported my friend's argument. I certainly looked feeble-bodied by the side of my brother and this friend. They were both hardier, physically stronger, and more daring. This friend's exploits cast a spell over me. He could run long distances and extraordinarily fast. He was an adept in high and long jumping. He could put up with any amount of physical punishment. He would often display his exploits to me and, as one is always dazzled when he sees in others the qualities that he lacks himself, I was dazzled by this friend's exploits. This was followed by a strong desire to be like him. I could hardly jump or run. Why should not I also be as strong as he?

Moreover, I was a coward. I used to be afraid of thieves, ghosts and serpents. I did not dare to stir out of doors at night. Darkness was a terror to me. It was almost impossible for me to sleep in the dark, as I would imagine ghosts coming from one direction, thieves from another and serpents from a third. I could not therefore bear to sleep without a light in the room. My friend knew all these weaknesses of mine. He would tell me that he could hold in his hand live serpents, could defy thieves and did not believe in ghosts.

All these had its due effect on me. I was beaten. It began to grow on me that meat-eating was good, that it would make me strong and daring, and that, if the whole country took to meat-eating, the English could be overcome.

A day was thereupon fixed for beginning the experiment. It had to be done in secret as my parents were orthodox Vaishnavas, and I was extremely devoted to them. I cannot say that I did not know then that I should have to deceive my parents if I began eating meat. But my mind was bent on the 'reform'. It was not a question of having something tasty to eat. I did not know that it had a particularly good taste. I wished to be strong and daring and wanted my countrymen also to be such. The zeal for the 'reform' blinded me. And having ensured secrecy, I persuaded myself that mere hiding the deed from parents was no departure from truth.

So the day came. We went in search of a lonely spot by the river, and there I saw, for the first time in my life, meat. There was baker's bread also. I did not like either. The goat's meat was as tough as leather. I simply could not eat it. I was sick and had to leave off eating.

I had a very bad night afterwards. A horrible dream haunted me. Every time I dropped off to sleep it would seem as though a live goat were crying inside me, and I would jump up sorry for what I had done. But then I would remind myself that meat-eating was a duty and so become more cheerful.

My friend was not a man to give in easily. He now began to cook various delicacies with meat. And for dining, no longer was the quiet spot on the river chosen, but a State house, with its dining hall and tables and chairs, about which my friend had made arrangements with the chief cook there.

Gradually I got over my dislike for bread, gave up my pity for the goats, and began to enjoy meat-dishes, if not meat itself. This went on for about a year. But not more than half a dozen meat-feasts were enjoyed in all. I had no money to pay for this 'reform'. My friend had therefore always to find the money. I had no knowledge where he found it. But find it he did, because he was bent on turning me into a meat-eater. But even his means must have been limited, and hence these feasts had necessarily to be few and far between.

Whenever I had occasion to indulge in these secret feasts, eating at home was impossible. My mother would naturally ask me to come and take my food and want to know the reason why I did not wish to eat. I would say to her, “I have no appetite today; there is something wrong with my digestion.” I knew I was lying, and lying to my mother. I also knew that, if my mother and father came to know of my having become a meat-eater, they would be deeply shocked. This knowledge was making me feel uneasy.

Therefore I said to myself: “Though it is essential to eat meat, and also essential to take up food 'reform' in the country, yet deceiving and lying to one's father and mother is worse than not eating meat. In their lifetime, therefore, meat-eating must be given up. When they are no more and I have found my freedom, I will eat meat openly, but until that moment arrives I will keep away from it.”

This decision I told to my friend, and I have never since gone back to meat.

5. Stealing

I have still to relate some of my failings during this meat-eating period and also previous to it, which date from before my marriage or soon after.

A relative and I became fond of smoking. Not that we saw any good in smoking, or liked the smell of a cigarette. We simply imagined a sort of pleasure in sending out clouds of smoke from our mouths. My uncle had the habit, and we should copy his example. But we had no money. So we began stealing stumps of cigarettes thrown away by my uncle.

The stumps, however, were not always available, and could not give out much smoke either. So we began to steal coppers from the servant's pocket-money in order to purchase Indian cigarettes. But the question was where to keep them. We could not of course smoke in the presence of elders. We managed somehow for a few weeks on these stolen coppers. In the meantime we heard that the stalks of a certain plant could be smoked like cigarettes. We got them and began this kind of smoking.

But we were far from being satisfied with such things as these. Our want of independence began to be painful. It was unbearable that we should be unable to do anything without the elders' permission. At last, in sheer disgust, we decided to commit suicide!

But how were we to do it? From where were we to get the poison? We heard that dhatura seeds were an effective poison. Off we went to the jungle in search of these seeds and got them. Evening was thought to be the auspicious hour. We went to Kedarji Mandir, put ghee in the temple-lamp, had the darshan and then looked for a lonely corner. But our courage failed us. Supposing we were not at once killed? And what was the good of killing ourselves? Why not rather put up with the lack of independence? But we swallowed two or three seeds nevertheless. We dared not take more. Both of us did not like to die, and decided to go to Ramji Mandir to calm ourselves, and to dismiss the thought of suicide.

I realized that it was not easy to commit suicide.

The thought of suicide ultimately resulted in both of us bidding goodbye to the habit of smoking and of stealing the servant's coppers for the purpose.

Ever since I have grown up, I have never desired to smoke and have always regarded the habit of smoking as barbarous, dirty and harmful. I have never understood why there is such a desire for smoking throughout the world. I cannot bear to travel in a compartment full of people smoking. I become choked.

But much more serious than this theft was the one I was guilty of a little later. I stole the coppers when I was twelve or thirteen, possibly less. The other theft was committed when I was fifteen. In this case I stole a bit of gold out of my meat-eating brother's armlet. This brother had run into a debt of about twenty-five rupees. He had on his arm an armlet of solid gold. It was not difficult to clip a bit out of it.

Well, it was done, and the debt cleared. But this became more than I could bear. I resolved never to steal again. I also made up my mind to confess it to my father. But I did not dare to speak. Not that I was afraid of my father beating me. No. I do not recall his ever having beaten any of us. I was afraid of the pain that I should cause him. But I felt that the risk should be taken; that there could not be cleansing without a clean confession.

I decided at last to write out the confession to submit it to my father, and ask his forgiveness. I wrote it on a slip of paper and handed it to him myself. In this note not only did I confess my guilt, but I asked adequate punishment for it, and closed with a request to him not to punish himself for my offence. I also pledged myself never to steal in future.

I was trembling as I handed the confession to my father. He was then confined to bed. His bed was a plain wooden plank. I handed him the note and sat opposite the plank.

He read it through, and tears trickled down his cheeks, wetting the paper. For a moment he closed his eyes in thought and then tore up the note. He had sat up to read it. He again lay down. I also cried. I could see my father's agony. If I were a painter I could draw a picture of the whole scene today. It is still so vivid in my mind.

Those tears of love cleansed my heart, and washed my sin away. Only he who has experienced such love can know what it is.

This sort of forgiveness was not natural to my father. I had thought that he would be angry, say hard things, and strike his forehead. But he was so wonderfully peaceful, and I believe this was due to my clean confession. A clean confession, combined with a promise never to commit the sin again, when offered before one who has the right to receive it, is the purest type of repentance. I know that my confession made my father feel absolutely safe about me, and increased greatly his affection for me.

6. My Father's Illness & Death

The time of which I am now speaking is my sixteenth year. My father, as we have seen, was bedridden. My mother, an old servant of the house, and I were attending on him. I had the duties of a nurse, which mainly consisted in dressing the wound, and giving my father his medicine. Every night I massaged his legs and retired only when he asked me to do so or after he had fallen asleep. I loved to do this service. I do not remember ever having neglected it. All the time at my disposal, after the performance of the daily duties, was divided between school and attending on my father. I would only go out for an evening walk either when he permitted me or when he was feeling well.

The dreadful night came. It was 10.30 or 11 p.m. I was giving the massage. My uncle offered to relieve me. I was glad and went straight to bed. In five or six minutes, however, the servant knocked at the door. I started with alarm. “Get up,” he said. “Father is very ill.” I knew of course that he was very ill, and so I guessed what 'very ill' meant that moment. I sprang out of bed.

“What is the matter? Do tell me!”

“Father is no more.”

So all was over! I felt very unhappy that I was not near my father when he died.

7. Glimpses of Religion

I have said before that there was in me a fear of ghosts and spirits. Rambha, my nurse, suggested, as a remedy for this fear, the repetition of Ramanama or name of God. I had more faith in her than in her remedy, and so at a very early age began repeating Ramanama to cure my fear of ghosts and spirits. This was of course short-lived, but the good seed sown in childhood was not sown in vain. I think it is due to the seed sown by that good woman Rambha that today Ramanama is a never failing remedy for me.

During part of his illness my father was in Porbandar. There every evening he used to listen to the Ramayana. The reader was a great devotee of Rama. He had a good voice. He would sing the verses and explain them, losing himself in the story and carrying his listeners along with him. I must have been thirteen at that time, but I quite remember being quite taken up by his reading. That laid the foundation of my deep devotion to the Ramayana. Today I regard the Ramayana of Tulsidas as the greatest book in all religious literature.

In Rajkot I learnt to be friendly to all branches of Hinduism and sister religions. For my father and mother would visit the Haveli as also Shiva's and Rama's temples, and would take or send us youngsters there. Jain monks also would pay frequent visits to my father, and would even go out of their way to accept food from us – non-Jains. They would have talks with my father on subjects religious and worldly.

He had besides, Mussalman and Parsi friends, who would talk to him about their own faiths, and he would listen to them always with respect, and often with interest. Being his nurse, I often had a chance to be present at these talks. These many things combined to teach me toleration for all faiths.

Only Christianity was at the time an exception. I developed a sort of dislike for it. And for a reason. In those days Christian missionaries used to stand in a corner near the high school and preach against Hindus and their gods. I could not endure this. About the same time, I heard of a well-known Hindu having been converted to Christianity. It was the talk of the town that when he was baptized, he had to eat beef and drink liquor, that he also had to change his clothes, and that from then on he began to go about in European costume including a hat. I also heard that the new convert had already begun abusing the religion of his ancestors, their customs and their country. All these things made me dislike Christianity.

But the fact that I had learnt to be tolerant to other religions did not mean that I had any living faith in God. But one thing took deep root in me – the conviction that morality is the basis of things and that truth is the substance of all morality.

A Gujarati verse likewise gripped my mind and heart. Its teaching – return good for evil – became my guiding principle. It became such a passion with me that I began numerous experiments in it. Here are those (for me) wonderful lines:

8. Preparation for England

My elders wanted me to continue my studies at college after school. There was a college in Bhavnagar as well as in Bombay, and as the former was cheaper, I decided to go there and join the Samaldas College. I went, but found everything very difficult. At the end of the first term, I returned home.

We had in Mavji Dave, who was a shrewd and learned Brahman, an old friend and adviser of the family. He had kept up his connection with the family even after my father's death. He happened to visit us during my holidays.

In conversation with my mother and elder brother, he inquired about my studies. Learning that I was at Samaldas College, he said: “The times are changed. And none of you can expect to succeed to your father's gadi (official work) without having had a proper education. Now as this boy is still pursuing his studies, you should all look to him to keep the gadi. It will take him four or five years to get his B. A. degree, which will at best qualify him for a sixty rupees' post, not for a Diwanship. If like my son he went in for law, it would take him still longer, by which time there would be a host of lawyers aspiring for a Diwan's post. I would far rather that you sent him to England. Think of that barrister who has just come back from England. How stylishly he lives! He could get the Diwanship for the asking. I would strongly advise you to send Mohandas to England this very year. Kevalram has numerous friends in England. He will give notes of introduction to them, and Mohandas will have an easy time of it there.”

Joshiji – that is how we used to call old Mavji Dave – turned to me and asked: “Would you not rather go to England than study here?” Nothing could have been more welcome to me. I was finding my studies difficult. So I jumped at the proposal and said that the sooner I was sent the better. My elder brother was greatly troubled in his mind. How was he to find the money to send me?

And was it proper to trust a young man like me to go abroad alone? My mother was very worried. She did not like the idea of parting with me. She had begun making minute inquiries. Someone had told her that young men got lost in England. Someone else had said that they took to meat; and yet another that they could not live there without liquor. “How about all this?” she asked me. I said: “Will you not trust me? I shall not lie to you. I promise that I shall not touch any of those things. If there were any such danger, would Joshiji let me go?”

“I can trust you,” she said. “But how can I trust you in a distant land? I am confused and know not what to do. I will ask Becharji Swami.”

Becharji Swami was originally a Modh Bania, but had now become a Jain monk. He too was a family adviser like Joshiji. He came to my help, and said: “I shall get the boy solemnly to take the three vows, and then he can be allowed to go.” I vowed not to touch wine, woman and meat. This done, my mother gave her permission.

The high school had a send-off in my honour. It was an uncommon thing for a young man of Rajkot to go to England. I had written out a few words of thanks. But I could scarcely read them out. I remember how my head reeled and how my whole frame shook as I stood up to read them. With my mother's permission and blessings, I set off happily for Bombay, leaving my wife with a baby of a few months. But on arrival there friends told my brother that the Indian Ocean was rough in June and July, and as this was my first voyage, I should not be allowed to sail until November.

Meanwhile my caste-people were agitated over my going abroad. A general meeting of the caste was called and I was summoned to appear before it. I went. How I suddenly managed to gather up courage I do not know. Fearless, and without the slightest hesitation, I came before the meeting.

The Sheth – the headman of the community – who was distantly related to me and had been on very good terms with my father, thus spoke to me:

“In the opinion of the caste your proposal to go to England is not proper. Our religion forbids voyages abroad. We have also heard that it is not possible to live there and keep to our religion. One is obliged to eat and drink with Europeans!” To which I replied: “I do not think it is at all against our religion to go to England. I intend going there for further studies. And I have already solemnly promised to my mother to keep away from three things you fear most. I am sure the vow will keep me safe.”

“But we tell you,” replied the Sheth, “that it is not possible to keep our religion there. You know my relations with your father and you ought to listen to my advice.” “I know those relations”, said I. “And you are as an elder to me. But I am helpless in this matter. I cannot change my decision to go to England. My father's friend and adviser who is a learned Brahman sees no objection to my going to England, and my mother and brother have also given me their permission.”

“But will you disregard the orders of the caste?”

“I am really helpless. I think the caste should not interfere in the matter.”

This made the Sheth very angry. He swore at me. I sat unmoved. So the Sheth ordered: “This boy shall be treated as an outcaste from today. Whoever helps him or goes to see him off at dock shall be punishable with a fine of one rupee four annas.”

The order had no effect on me, and I took my leave of the Sheth. But I wondered how my brother would take it. Fortunately he remained firm and wrote to assure me that I had his permission to go, in spite of the Sheth's order.

A berth was reserved for me by my friends in the same cabin as that of Shri Tryambakrai Mazmudar, the Junagadh Vakil.

They also asked him to help me. He was an experienced man of mature age and knew the world. I was yet a youth of eighteen without any experience of the world. Shri Mazmudar told my friends not to worry about me.

I sailed at last from Bombay on the 4th of September.

9. On board the ship

I was not used to talking English, and except for Shri Mazmudar all the other passengers in the second saloon were English. I could not speak to them. For I could rarely follow their remarks when they came up to speak to me, and even when I understood I could not reply. I had to frame every sentence in my mind before I could bring it out. I was innocent of the use of knives and forks and had not the boldness to inquire what dishes on the menu were free of meat. I therefore never took meals at table but always had them in my cabin, and they consisted principally of sweets and fruits which I had brought with me. Shri Mazmudar had no difficulty, and he mixed with everybody. He would move about freely on deck, while I hid myself in the cabin the whole day, only going up on deck when there were but few people. Shri Mazmudar kept pleading with me to associate with the passengers and to talk with them freely.

He told me that lawyers should have a long tongue, and related to me his legal experience. He advised me to take every possible opportunity of talking English and not to mind making mistakes which were obviously unavoidable with a foreign tongue. But nothing could make me conquer my shyness. An English passenger, wanting to be nice to me, drew me into conversation. He was older than I. He asked me what I ate, what I was, where I was going, why I was shy, and so on. He also advised me to come to table. He laughed at my insistence on not eating meat, and said in a friendly way when we were in the Red Sea: “It is all very well so far but you will have to change your decision in the Bay of Biscay. And it is so cold in England that one cannot possibly live there without meat.”

“But I have heard that people can live there without eating meat,” I said.

“Rest assured it is a lie,” said he. “No one, to my knowledge, lives there without being a meat-eater.

Don't you see that I am not asking you to take liquor, though I do so? But I do think you should eat meat, for you cannot live without it.”

“I thank you for your kind advice, but I have solemnly promised to my mother not to touch meat, and therefore I cannot think of taking it. If it be found impossible to get on without it, I will far rather go back to India than eat meat in order to remain there.”

We entered the Bay of Biscay, but I did not begin to feel the need either of meat or liquor.

We reached Southampton, as far as I remember, on a Saturday. On the boat I had worn a black suit, the white flannel one, which my friends had got me, having been kept especially for wearing when I landed. I had thought that white clothes would suit me better when I stepped ashore, and therefore, I did so in white flannels. Those were the last days of September, and I found I was the only person wearing such clothes. I left in charge of an agent of Grindlay and Co. all my luggage including the keys, seeing that many others had done the same and I thought I must do like them.

Someone on board had advised us to put up at the Victoria Hotel in London. Shri Mazmudar and I accordingly went there. The shame of being the only person in white clothes was already too much for me. And when at the Hotel I was told that I should not get my things from Grindlay's the next day, it being a Sunday, I felt very bad.

Dr. Mehta to whom I had wired from Southampton, called at about eight o'clock the same evening. He gave me a hearty greeting. He smiled at my being in white flannels. As we were talking, I casually picked up his top-hat, and trying to see how smooth it was, passed my hand over it the wrong way and disturbed the fur. Dr. Mehta looked somewhat angrily at what I was doing and stopped me. But the mischief had been done.

The incident was a warning for the future, and Dr. Mehta gave me my first lesson in European etiquette.

“Do not touch other people's things,” he said. “Do not ask questions as we usually do in India on first acquaintance; do not talk loudly; never address people as 'sir' whilst speaking to them as we do in India; only servants and subordinates address their masters that way.” And so on and so forth. He also told me that it was very expensive to live in a hotel and recommended that I should live with a private family.

Shri Mazmudar and I found the hotel to be a trying affair. It was also very expensive. There was, however, a Sindhi fellow-passenger from Malta who had become friends with Shri Mazmudar, and as he was not a stranger to London, he offered to find rooms for us. We agreed, and on Monday, as soon as we got our baggage, we paid up our bills and went to the rooms rented for us by the Sindhi friend. I remember my hotel bill came to £ 3, an amount which shocked me. And I had practically starved in spite of this heavy bill! For I could relish nothing. When I did not like one thing, I asked for another, but had to pay for both just the same. The fact is that all this while I had depended on the foodstuffs which I had brought with me from Bombay.

I was very uneasy even in the new rooms. I would continually think of my home and country, and of my mother's love. At night the tears would stream down my cheeks, and home memories of all sorts made sleep out of the question. It was impossible to share my misery with anyone. And even if I could have done so, where was the use? I knew of nothing that would soothe me. Everything was strange – the people, their ways, and even their dwellings. I was a complete stranger to English etiquette and continually had to be on my guard.

There was the additional inconvenience of the vegetarian vow. Even the dishes that I could eat were tasteless. I thus found myself between Scylla and Charybdis. England I could not bear, but to return to India was not to be thought of. Now that I had come, I must finish the three years, said the inner voice.

Part II: In England as student

10. In London

Dr. Mehta went on Monday to the Victoria Hotel expecting to find me there. He discovered that we had left, got our new address, and met me at our rooms. Dr. Mehta inspected my room and its furniture and shook his head in disapproval. “This place won't do,” he said. “We come to England not so much for the purpose of studies as for gaining experience of English life and customs. And for this you need to live with a family. But before you do so, I think you had better be for a period with – I will take you there.”

I gratefully accepted the suggestion and removed to the friend's rooms. He was all kindness and attention. He treated me as his own brother, initiated me into English ways and manners, and accustomed me to talking the language.

My food, however, became a serious question. I could not relish boiled vegetables cooked without salt or spices. The landlady was at a loss to know what to prepare for me. We had oatmeal porridge for breakfast, which was fairly filling, but always I starved at lunch and dinner. The friend continually reasoned with me to eat meat, but I always pleaded my vow and then remained silent.

Both for luncheon and dinner we had spinach and bread and jam too. I was a good eater and had a big appetite; but I was ashamed to ask for more than two or three slices of bread, as it did not seem correct to do so. Added to this, there was no milk either for lunch or dinner. The friend once got disgusted with this state of things, and said: “Had you been my own brother, I would have sent you away. What is the value of a vow made before an illiterate mother and in ignorance of conditions here? It is no vow at all. It would not be regarded as a vow in law. It is pure superstition to stick to such a promise. And I tell you this persistence will not help you to gain anything here. You confess to having eaten and liked meat. You took it where it was absolutely unnecessary, and will not where it is quite essential. What a pity!”

But I was unyielding.

Day in and day out the friend would argue, but I had an eternal no to face him with. The more he argued, the firmer I became. Daily I would pray for God's protection and get it. Not that I had any idea of God. It was faith that was at work – faith of which the seed had been sown by the good nurse Rambha.

I had not yet started upon regular studies. In India I had never read a newspaper. But here I succeeded in cultivating a liking for them by regular reading. This took me hardly an hour. I therefore began to wander about. I went out in search of a vegetarian restaurant. I hit on one in Farringdon Street.

The sight of it filled me with the same joy that a child feels on getting a thing after its own heart.

Before I entered I noticed books for sale exhibited under a glass window near the door. I saw among them Salt's Plea For Vegetarianism. This I purchased for a shilling and went straight to the dining room. This was my first hearty meal since my arrival in England. God had come to my aid. I read Salt's book from cover to cover and was very much impressed by it. From the date of reading this book, I may claim to have become a vegetarian by choice. I blessed the day on which I had taken the vow before my mother. The choice was now made in favour of vegetarianism, the spread of which henceforward became my mission.

11. Playing the English Gentleman

Meanwhile my friend had not ceased to worry about me. He one day invited me to go to the theatre. Before the play we were to dine together at the Holborn Restaurant.

The friend had planned to take me to this restaurant evidently imagining that modesty would prevent me from asking any questions. And it was a very big company of diners in the midst of which my friend and I sat sharing a table between us. The first course was soup. I wondered what it might be made of, but did not dare ask the friend about it. I therefore summoned the waiter. My friend saw the movement and sternly asked across the table what was the matter. With considerable hesitation I told him that I wanted to inquire if the soup was a vegetable soup. “You are too clumsy for decent society,” he angrily exclaimed. “If you cannot behave yourself, you had better go. Feed in some other restaurant and await me outside.”

This delighted me. Out I went. There was a vegetarian restaurant close by, but it was closed. So I went without food that night. I accompanied my friend to the theatre, but he never said a word about the scene I had created. On my part of course there was nothing to say.

That was the last friendly quarrel we had. It did not affect our relations in the least. I could see and appreciate the love underlying all my friend's efforts, and my respect for him was all the greater on account of our differences in thought and action.

But I decided that I should put him at ease, that I should assure him that I would be clumsy no more, but try to become polished and make up for my vegetarianism by cultivating other accomplishments which fitted one for polite society. And for this purpose I undertook the all too impossible task of becoming an English gentleman.

The clothes after the Bombay cut that I was wearing were, I thought, unsuitable for English society, and I got new ones at the Army and Navy Stores. I also went in for a chimney-pot hat costing nineteen shillings – an excessive price in those days. Not content with this, I wasted ten pounds on an evening suit made in Bond Street, the centre of fashionable life in London; and got my good and noble-hearted brother to send me a double watch chain of gold. It was not correct to wear a readymade tie and I learnt the art of tying one for myself. While in India the mirror had been a luxury permitted on the days when the family barber gave me a shave.

Here I wasted ten minutes every day before a huge mirror, watching myself arranging my tie and parting my hair in the correct fashion.

My hair was by no means soft, and every day it meant a regular struggle with the brush to keep it in position. Each time the hat was put on and off, the hand would automatically move towards the head to adjust the hair, not to mention the other civilized habit of the hand every now and then doing the same thing when sitting in polished society.

As if all this were not enough to make me look the thing, I directed my attention to other details that were supposed to go towards the making of an English gentleman. I was told it was necessary for me to take lessons in dancing, French, and elocution or speechmaking.

French was not only the language of neighbouring France, but it was a language understood all over Europe where I had a desire to travel.

I decided to take dancing lessons at a class and paid down £3 as fees for a term. I must have taken about six lessons in three weeks.

But it was beyond me to achieve anything like rhythmic motion. I could not follow the piano and hence found it impossible to keep time. What then was I to do? The recluse in the fable kept a cat to keep off the rats, and then a cow to feed the cat with milk, and a man to keep the cow and so on.

My ambitions also grew like the family of the recluse. I thought I should learn to play the violin in order to cultivate an ear for Western music. So I invested £3 in a violin and something more in fees.

I sought a third teacher to give me lessons in elocution and paid him a preliminary fee of a guinea. He recommended Bell's Standard Elocutionist as the textbook, which I purchased. And I began with a speech of Pitt's.

But soon I began to ask myself what the purpose of all this was.

I had not to spend a lifetime in England, I said to myself. What then was the use of learning elocution?

And how could dancing make a gentleman of me? The violin I could learn even in India. I was a student and ought to go on with my studies. I should qualify myself to become a barrister. If my character made a gentleman of me, so much the better. Otherwise I should give up the ambition.

These and similar thoughts possessed me, and I expressed them in a letter which I addressed to the elocution teacher, requesting him to excuse me from further lessons.

I had taken only two or three. I wrote a similar letter to the dancing teacher, and went personally to the violin teacher with a request to dispose of the violin for any price it might fetch. She was rather friendly to me, so I told her how I had discovered that I was pursuing a false idea. She encouraged me in my decision to make a complete change.

This infatuation must have lasted about three months. Being particular about dress persisted for years. But henceforward I became a student.

12. Changes

Let no one imagine that my experiments in dancing and the like marked a stage of indulgence in my life. The reader will have noticed that even then I knew what I was doing and my expenses were carefully calculated.