11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

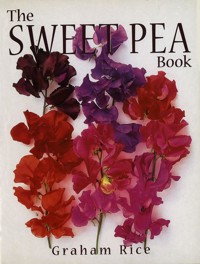

The sweet pea is one of the most popular and evocative of summer flowers, loved for its unsurpassed fragrance, range of colours and ease of cultivation. Authoritative and inspiring, The Sweet Pea Book covers: History of sweet peas; Classification; Descriptions of all available varieties; Raising sweet peas; Growing and breeding sweet peas; Problems with sweet peas (peasts and diseases); Fragrance; Sweet peas in the garden; Sweet peas in the house (cut flowers); Exhibiting sweet peas; Sweet peas in the United States; Sweet peas in Australia; Illustrated in colour throughout by studio plates, plant portraits and plant association pictures by the author and the award-winning American garden photographer Judy White.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 308

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Dedication

It was at my desk, in Pennsylvania, working on this book, that I heard the first plane had hit the World Trade Center. For some time afterwards, it was hard to write about sweet peas as we mourned for so many strangers, so needlessly dead, and sorrowed for the loved ones left behind to grieve.

But the book was finished and you have it in your hand. I will not presume to dedicate a mere gardening book to the memory of so many, so tragically lost. I simply urge you to use its advice to help you make your small part of the world more beautiful.

...Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st, ‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’ that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

From “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats

© Graham Rice 2002

First published in the UK in 2002 by B T Batsford, London, UK

All photography © judywhite/GardenPhotos.com except where indicated on page 144.

Title page picture ‘Peacock’.

eISBN 9781849942126

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Batsford

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

Contents

Introduction and notes to readers

Chapter 1

From the wild to our gardens

Chapter 2

Fragrance

Chapter 3

In the garden

Chapter 4

Dwarf sweet peas

Chapter 5

Sweet peas in containers

Chapter 6

Classification of sweet peas

Chapter 7

The sweet peas: descriptions

Chapter 8

Wild annualLathyrus

Chapter 9

Raising sweet peas from seed

Chapter 10

Care and culture of sweet peas

Chapter 11

Creating new sweet peas

Chapter 12

Solving sweet pea problems

Chapter 13

In the house

Chapter 14

The basics of exhibiting

Chapter 15

Sweet peas in the United States

Appendix I

Awards to sweet peas

Appendix II

Where to buy sweet pea seeds

Appendix III

Further information

Glossary

Index of varieties

Acknowledgements

Picture credits

Introduction

This is a book for gardeners, for gardeners who grow sweet peas in beds and borders, tubs and even hanging baskets; for gardeners who sow a packet of mixed seed in the spring or dozens of individual varieties in the autumn; for gardeners who grow sweet peas for their fragrance and their colour and for cutting for the house.

Sweet peas are not difficult to grow. I will outline how to go about it with the least possible time and trouble, but to grow them well requires careful attention; this, also, I explain. Growing sweet peas up a clump of brushwood or a wigwam of bamboo canes is relatively straightforward and works well, but few gardeners integrate sweet peas into their border plantings or use them to create inspiring and attractive plant associations; I have many suggestions which I hope will provide inspirations in using these versatile flowers.

The explosion of interest in hanging baskets and other containers seems to have swept along without carrying the sweet pea in its wake, yet both traditional varieties and new types can be grown in containers: I will explain how and provide some enticing ideas for plant combinations.

Much of what has been written on sweet peas over the decades has been aimed at exhibitors, but these devotees are but a small minority of those enthusiastic growers for whom sweet peas are such a delight. Exhibitors have pioneered ways of growing sweet peas, researched their history, their peculiarities and their pests and diseases; they have raised many new varieties. Their contribution to sweet pea growing is enormous – but they are still a minority: in the United States they are practically non-existent. I discuss exhibiting, and breeding, sweet peas but my interest is more to help gardeners grow better sweet peas and use them more widely and more imaginatively in gardens.

Sweet peas were once the most widely grown of flowers; this may no longer be true, but these are exciting times in the sweet pea world. We have new dwarf sweet peas for hanging baskets, we have new varieties in the highly scented old-fashioned style, and we even have a revival in tall varieties without tendrils. There is also the possibility of a truly yellow sweet pea on the distant horizon, rather than far beyond it. Sweet peas are definitely back. Not as a show flower, but in gardens. It starts here.

NOTES TO READERS

I have used the word variety, rather than cultivar, throughout in recognition of the fact that this is the term which most gardeners actually use for a cultivated variety. I apologize to those purists who may be offended by this affront to botanical correctness.

This book is written with both British and American readers in mind. Occasionally, there are remarks which may seem simplistic to readers in one country but which are helpful to those in the other and I would ask that readers not be irritated by this attempt to please all the readers all of the time.

The flowers in the studio photographs came from plants grown at Unwins Seeds near Cambridge, the Royal Horticultural Society’s Garden at Wisley, Surrey and Sweet Pea Gardens, Surrey; our thanks go to all. Flowers also came from my own garden.

Chapter One

From the wild to our gardens

The native habitat of the wild sweet pea, Lathyrus odoratus, and its earliest introduction into the gardens of Western Europe, is a surprisingly contentious issue, provoking wildly contrasting opinions even today. Sweet peas have been taken all over the world, the robustness of their seeds having certainly been a help; whatever varieties are taken and grown, when they escape into a suitable climate they eventually revert to something approaching a wild type. This causes confusion.

Sicily, China, Malta, Sri Lanka – all have been suggested as the wild home of the sweet pea. But there is one aspect of the historical story on which most people now agree: in 1695 Francisco Cupani recorded the sweet pea as newly seen in Sicily. Cupani was a member of the order of St Francis, but he may not actually have been a monk as we have always assumed. He was in charge of the botanical garden at Misilmeri (15km/9 miles from Palermo) in Sicily and it is assumed that his garden was attached to the monastery although it is not entirely clear if his sweet pea was actually growing in the garden or wild in the surrounding area. In 1696, before Linnaeus simplified plant nomenclature, Cupani published a written description of the plant which he called Lathyrus distoplatyphylos, hirsutus, mollis, magno et peramoeno, flore odoro.

In 1699 he sent seed to Dr Casper Commelin, a botanist at the School of Medicine in Amsterdam, who included what is the first illustration of the plant in his account of the plants at the School published in 1701 where he records that the seeds came from Cupani. While there is no concrete contemporary evidence, it also seems clear that Cupani sent seed to Dr Robert Uvedale at the same time.

Dr Uvedale was a teacher who lived at Enfield in Middlesex and was a noted enthusiast for new and unusual plants; he enjoyed a very wide circle of notable friends and his was a well-known and much-visited garden. The first evidence of the plant being grown by Uvedale comes in 1700 on a herbarium specimen made by Dr Leonard Plukenet now at the British Museum (Natural History) in London. A note on the specimen refers to it having been collected from Uvedale’s garden. British botanical pioneer John Ray also picked up on this new introduction, describing it in his Historia Plantarum of 1704 as: “Lathyrus major e Siciliae; a very sweet-scented Sicilian flower with a red standard; the lip-like petals surrounding the keel are pale blue.”

So, Cupani noticed the sweet pea, his being the first printed reference. He definitely sent seed to Commelin and it seems most likely that he also sent seed to Uvedale. So far, so good.

There has long been a theory that sweet peas originated in Sri Lanka (Ceylon). In 1753 Linnaeus uses the name Lathyrus zeylandicus for a pink and white-flowered species supposedly originating in that country and this, with other red herrings, led the great authority Bernard Jones to believe as late as 1986 that sweet peas did, indeed, originate there. A much-respected earlier authority, E. R. Janes, held a similar conviction in 1953.

This opinion was fostered by Cornell University which, in 1897, in one of a series of otherwise excellent publications on sweet peas, asserted that Cupani himself had brought the pink and white pea from Ceylon to Italy. There are no wild sweet peas in Sri Lanka and this is confirmed by the Flora of Ceylon published in 1980.

Malta has also been suggested as a location for the wild home of the sweet pea, and one still propounded by Charles W. J. Unwin in the most recent edition of his classic Sweet Peas: Their History, Development, Culture (1986) and also in The Unwins Book of Sweet Peas by Colin Hambidge (1996). I regret to say that both are wrong but must also admit that I too was wrong when I put the same notion into print more recently myself. Charles Unwin reported “wild” sweet peas in Malta but there seems little doubt that these were the result of escape from gardens. They are not even comfortably naturalized there as it seems they are unusually difficult to grow in Malta owing to a soil-borne disease.

Other locations suggested for the origin of sweet peas have been China, as recently as 1985, and also South America: the variety ‘Quito’ was collected from a garden in that city, the capital of Ecuador; ‘Matucana’ was found in a place of that name in Peru. Confusingly, in an echo of the naming of Scilla peruviana, which originates in Spain, Portugal and Morocco, ‘Sicilian Pink’ and ‘Sicilian Fuchsia’ were also found at Matucana in Peru – they were named in honour of Francisco Cupani. These were undoubtedly the descendants of introductions by early colonists.

The original colour of these plants is described by Commelin, from plants he raised from Cupani’s seed, as having ‘a purple standard, the remaining petals are sky blue’. Ray describes them as ‘with a red standard; the lip-like petals surrounding the keel are pale blue’. Early illustrations confirm this although, of course, the colour cannot be firmly established from early herbarium specimens. It has been inferred from some texts that there was also a white form; the non-existent form from Sri Lanka was said to be a pink and white bicolour.

In the 1970s the sweet pea pioneer Dr Keith Hammett collected seed of wild sweet peas from Sicily and these are now available under the name ‘Original’ or ‘Cupani’s Original’. If you want to grow the true wild sweet pea, this is it.

Early developments in gardens

The first sweet peas were offered for sale in 1724 as ‘sweet sented pease’, and the first cultivar name, ‘Painted Lady’, is found in the writings of Philip Miller in 1731 who describes it as ‘pale red’ and who also mentions the white form; so, with Cupani’s original, that makes three distinct forms in cultivation at this time. In 1775 a scarlet one is mentioned, in 1778 a seedsman offered the same white, purple and ‘Painted Lady’, while in 1782 another seedsman is recorded as selling all four: scarlet, white, purple and ‘Painted Lady’.

It seems extraordinary but by 1788 William Curtis was writing in the Botanical Magazine: “There is scarcely a plant more generally cultivated than the Sweet Pea... general cultivation extends to two only, one with blossoms perfectly white, and the other white and rose-coloured, commonly called the ‘Painted Lady Pea’.”

In 1793 John Mason, founder of the company which eventually evolved into the Hurst breeders and packet seed brand, and who traded from a pub in London’s Fleet Street (how the seed trade has changed...), listed five varieties: purple, white, ‘Painted Lady’, scarlet and black; the “black” was probably a dark purple or maroon. By the time of Philip Miller’s The Gardener’s Dictionary in 1807 there is an interesting mention of the height of the sweet peas of that time – which is given as “from three to four feet high”. Modern varieties are noticeably taller, even when poorly grown, so it is clear that over the years breeders and gardeners have tended to select the more vigorous plants from which to save seed, so increasing the height of plants. This point also tends to support the view that the ‘Painted Lady’ we grow today, which is as tall as other varieties, is not a direct descendant of the original form, but a later throwback from a more modern variety. This is reinforced by the fact that Miller also quotes them all as having just two flowers per stem (as has Dr Hammett’s recent introduction from Sicily); in many cases breeders have increased this to three or four.

The year of 1840 seems to mark the end of the first phase of development, most of which took place more or less by chance. At this time The Ladies’ Flower Garden of Ornamental Annuals gives the following account: “There are six distinct kinds of sweet peas in constant cultivation, all of which, with very few exceptions, come true from seed. There are the purple, which has a standard of deep reddish purple, the wings pinkish, and the keel nearlywhite...; the New Painted Lady, which has a standard of a deep rose colour, the wings pale rose, and the keel pure white...; the Old Painted Lady, which has wings and keel white and the standard flesh-coloured; the blue, which has the wings and keel a pale blue and the standard dark bluish purple; and the violet, which has the keel pale violet, the wings a deep violet, and the standard a dark reddish purple.”

In 1837 James Carter of Holborn in London, the founder of what became Carters Tested Seeds, introduced the first flaked variety (then called striped) and by 1860 he listed nine varieties plus the first “yellow”, in fact cream, and another said to be the result of crossing L. odoratus with the blue-flowered perennial L. nervosus (Lord Anson’s pea), from South America. Such a cross has never been made but the “result” was named ‘Blue Edged’. Rechristened ‘Blue Hybrid’, this wired variety with a slender margin of blue on an otherwise white flower was awarded a First Class Certificate (the top award) by the Royal Horticultural Society in 1883.

It was not the first sweet pea to gain an RHS award. ‘Scarlet Invincible’, in fact more carmine than scarlet, gained an FCC in 1867; at this time development was starting to hasten. In 1870 James Vick of Rochester, New York, listed scarlet, scarlet striped with white, white, purple striped with white, ‘Painted Lady’, ‘Blue Edged’, black, black with light blue, and ‘Scarlet Invincible’. In 1878 Suttons introduced ‘Butterfly’, similar to ‘Blue Edged’, and in all by 1881, as things began to gather pace, there were 21: purple, white, large dark purple, scarlet, black, purple striped white, ‘New Painted Lady’, ‘Large Dark Purple’, yellow, ‘Blue Edged’, ‘Scarlet Invincible’, scarlet striped with white, ‘Black Invincible’, ‘Crown Princess of Russia’, ‘Fairy Queen’, ‘Purple Invincible’, ‘Invincible Striped Violet Queen’, ‘Heterosperma’, ‘The Queen’, ‘Captain Clarke’, and ‘Imperial Purple’.

These varieties had either plain upright standards or hooded standards, some with symmetrical notches towards their base; the wings tended to be folded around the keel.

Henry Eckford and the coming of the Grandifloras

As the century approached its turn, an ever-increasing number of varieties appeared. Some were only listed for a year or two before disappearing, some were named and never listed by commercial seed houses but distributed personally, soon to fade away. It seems clear that, as is so often the case when a new flower captures the public’s attention (and its purses), many “new” introductions were no better, and little different from their predecessors.

‘Invincible Carmine’ from Thomas Laxton of Bedford (better known for his ‘Laxton’s Superb’ and other apples) was a significant introduction which was awarded an FCC in 1883, and is also notable as the first variety to be the result of deliberate hand pollination. And 1882 saw the award of an FCC to the first of Henry Eckford’s introductions, ‘Bronze Prince’.

Eckford transformed the flower, developing improved form, larger size and new colours yet retaining the fragrance which was such a striking feature of the original wild species. By 1900 he had introduced 115 varieties out of a total grown at the time, including many highly transient varieties, of 264. Henry Eckford had success with breeding other flowers before his involvement with the sweet pea; while head gardener to the Earl of Radnor, he raised many new varieties of pelargonium, verbena and dahlia. He then went to work for Dr Sankey of Sandywell near Gloucester specifically to raise new varieties. He arrived in 1870 and set methodically to crossing, selecting and fixing new varieties; ‘Bronze Prince’ was the first to be released. He moved with the doctor to Shropshire, then in 1888 set up his breeding and trials fields in the Shropshire town of Wem.

‘Prima Donna’, a classic Grandiflora and at the end of the 19th century considered one of the best.

This page from the catalogue of D.W. Croll of Aberdeen shows part of the range of sweet peas available in 1936.

In the years until the end of the century Eckford raised a generous succession of Grandiflora sweet peas, so called because their flowers were noticeably larger than those few derived directly from Cupani’s original. These included ‘Princess of Wales’ (1888), ‘Captain of the Blues’ (1889), ‘Prima Donna’ (1896) and ‘Lady Grisel Hamilton’ (1898).

The powerful demand from the United States for new varieties soon began to drive Eckford’s work. In 1886 his varieties were offered in the United States by James Breck and in the early 1890s demand took off, led by the enthusiasm of the Reverend W. T. Hutchins. He, Breck, Peter Henderson, W. Atlee Burpee, D. M. Ferry, the Sunset Seed Company, J. C. Vaughan and C. C. Morse & Co, to mention just some of the American seedsmen who took up sweet peas, introduced many of Eckford’s varieties and soon began launching their own. In 1897 development in the United States was also well under way, both W. Atlee Burpee from California and Henry Eckford from Shropshire listing seven new introductions.

Notable American varieties of these times were ‘Blanche Ferry’ (1889), ‘America’ (1897), ‘Janet Scott’ (1903) and ‘Flora Norton’ (1904); it is clear, even from this short list, that many varieties regarded today as classic old-fashioned English sweet peas, and sometimes even attributed to Eckford, are, in fact, American in origin. It was in this period that Burpee launched the first dwarf variety, ‘Cupid’ (1893, discovered by Morse), which was awarded an AM by the RHS.

‘Blanche Ferry’, developed from ‘Old Painted Lady’, was actually the first sweet pea to originate in the United States. For 25 years a quarryman’s wife in New York State grew ‘Painted Lady’; she grew it, and each year she saved her own seed from plants grown, it seems, on limestone ledges where the soil was unusually shallow. After about 15 years the plants developed such compact growth that they no longer needed staking and also tended to produce all their flowers at about the same time. Her selection came to the notice of D. M. Ferry & Co, who introduced the variety as ‘Blanche Ferry’ in 1889. It was the first sweet pea to be illustrated in colour in an American seed catalogue.

This variety went on to become the progenitor of many American-bred introductions including the early-flowering sorts. In the year that ‘Blanche Ferry’ was released, a few early-flowering plants were noticed among it on the Ferry trial fields. In 1894 this was introduced as ‘Extra Early Blanche Ferry’. Although weak in growth out of doors, under glass it performed well and gave a crop in midwinter.

Development continued and in 1898 W. Atlee Burpee introduced ‘Earliest of All’, also derived from ‘Blanche Ferry’, followed in 1902 by ‘Extreme Early, Earliest of All’. By this time the tendency of seedsmen to hyperbolize was all too evident. These were the precursors of the winter-flowering kinds and Anton C. Zvolaneck, originally in New Jersey and later in California, was instrumental in creating these, at first by crossing an early-flowering selection of ‘Lottie Eckford’ with ‘Blanche Ferry’. All these ‘earlies’ were of Grandiflora type until, in 1913, Anton Zvolaneck released his early-flowering Spencers; ‘Zvolaneck’s Rose’ was the outstanding early variety of the era. Frank Cuthbertson worked on the same group for C. C. Morse & Co, as did Dr J. H. Franklin for Waller-Franklin and George Kerr for W. Atlee Burpee.

Soon after the release of ‘Blanche Ferry’, in 1896 James Vicks’ Sons introduced the first “double”-flowered variety, the effect created by the presence of an extra standard, sometimes two, and today referred to as duplex; this too was derived from ‘Blanche Ferry’; it was named ‘Bride of Niagara’ although W. T. Hutchins in a contemporary account says, with a tone of slight condescension: “It does produce about 30 per cent of so-called doubles.” He continued: “Many of the improved varieties, when well grown, show a vigour of habit that sometimes makes double stems, but oftener they break up the standard of the blossom into several imperfect standards, and occasionally the wings are duplicated. No sound dictum of taste would consider this an advantage or an improvement in this flower.”

Development continued apace, and in 1911 an astonishing total of 135 new introductions were made in the United States and Britain combined.

The Spencer sweet pea

By 1900 sweet peas were sufficiently popular in Britain for a Sweet Pea Bi-Centenary Celebration to be staged in London. This must have been a staggering event. One of the competitive classes called for 100 bunches of sweet peas in ten different shades; another for 48 bunches in no fewer than 36 varieties. There was even a small subsection for amateurs who actually grew their own flowers rather than employing a gardener! Classes were sponsored by names still known for their sweet peas today: Carters, Suttons and Robert Bolton.

Following this meeting the National Sweet Pea Society (NSPS) was formed, and the following year, in 1901, held its first show – at the Royal Aquarium in Westminster! The hall is now known as the Central Hall, Westminster.

The day before the show opened rumours began to spread around the hall about a revolutionary new sweet pea. Silas Cole did little but tease the other exhibitors and it was not until a few minutes before the deadline the following morning that he staged his table decoration of his new variety – which stunned everyone.

His ‘Countess Spencer’ was deep rose pink in colour and a contemporary report stated that “it seemed as if nature has been so lavish that the material in its standard had to be closely pleated to hold it in position. It was beflowered and befrilled.” So the waved standard had arrived and although Eckford’s Grandifloras, and those from other breeders, continued to dominate in number for some years, in impact ‘Countess Spencer’ and its derivatives were instantly the favourites.

Silas Cole was Head Gardener for the Earl Spencer at Althorp Park in Northamptonshire, as had been his father before him. A leading exhibitor of flowers, in 1898 he crossed two popular Grandifloras of the time, ‘Lovely’ and ‘Triumph’, and saved the seed. In the following year he picked out a few promising seedlings, and these he crossed with Eckford’s ‘Prima Donna’. He sowed the seeds, and in 1900 when he inspected his rows of one of the resulting seedlings, he found one plant that was more vigorous, and later flowering, than the others. Cole was astonished to see that the flowers were much larger than his Grandifloras, by about 25 per cent, and that the standards were noticeably ruffled. Of course, he saved seed – just one pod, containing five seeds.

‘Superfine’ (Left) and ‘Smiles’, two novelties from Unwins Seeds for the autumn of 1933.

The following year he sowed his five seeds: three were eaten by mice, but from the resulting two plants he cut enough blooms of what he named ‘Countess Spencer’ to take to the first NSPS show at the Royal Aquarium. It was unanimously awarded an FCC.

He saved 90 seeds that year, sowed them in 1902 and, astonishingly, every one is said to have come true. But it was a cold, wet summer and his 90 plants produced only 3,000 seeds. Two thousand two hundred of these were sold to Robert Sydenham of Birmingham who sent them to America to be bulked up in a more suitable climate. They came back startlingly mixed.

Silas Cole himself, writing in NSPS Annual for 1906, while mentioning that ‘no variety introduced in recent years was received with such a chorus of approval’ also admits that ‘no variety has caused more disappointment and annoyance’ owing to its habit of sporting. He attempts to promote this as a ‘blessing in disguise’ but to most it was indeed a disappointment.

The year after Silas Cole found his sport, W. J. Unwin, a cut-flower grower at Histon near Cambridge in England, returned home from church one Sunday morning and took a stroll through the rows of sweet peas growing alongside his house on what was then called Dog Kennel Lane, now the Impington Road. There he spotted a similar, but not identical, variant in his rows of ‘Prima Donna’ grown for cut flowers. The flower he noticed was pale pink, slightly larger than the flowers of ‘Prima Donna’, and with its petals slightly waved. His son Charles W. J. Unwin specifically makes the point in the early editions of his book that this was a sport and not the result of hybridization.

W. J. Unwin used this breakthrough as the foundation for a business selling sweet pea seed, rather than cut flowers. He named his find ‘Gladys Unwin’, after his elder daughter, and, after ensuring that it was properly fixed and true, it was introduced.

The Unwins Type of sweet pea was popular for some years and, between 1905 and 1909, 15 varieties were introduced, most, but not all, raised by W. J. Unwin. But the larger form and extra waviness of the Spencer type dominated and W. J. Unwin himself developed Spencers, incorporating blood from the Unwins type, to create an increasing range of, fixed, Spencer varieties.

So two similar waved forms were found in 1900 and 1901, both associated with ‘Prima Donna’. But what, you might ask, was Henry Eckford doing while all this was going on at Althorp and Histon? Becoming nervous of his place as the pre-eminent sweet pea breeder in the world, perhaps. For a Mr E. Viner, an amateur gardener from Frome in Somerset, also found a waved type. It is worth quoting from a letter from Mr Viner to William Cuthbertson, of Dobbie & Co in Edinburgh:

“It must have been the spring of 1900.

I procured a few seeds of Prima Donna and Lovely, with the object of choosing the one I liked the best, and my choice fell on Prima Donna. I quite discarded Lovely.

The following year I grew Prima Donna from seed I saved myself, and quite late in the season I noticed a spray of two blooms on Prima Donna at the extremity of a shoot with a peculiarly crimpled character.

I marked them and allowed it to seed (no other flowers appeared), and I obtained seven good seeds. The following year I planted them in due course and all germinated, and to my delight five retained the wavy character; the other two were Prima Donna pure.

But the waved ones were glorious in the fine weather of early July... at the suggestion of others it was named Nellie Viner. Later in the season I sent blooms to Mr Eckford, to whom I eventually sold. Therefore, Mr Eckford’s variety was a sport from Prima Donna.”

In recognition of his important contribution to the development of the sweet pea, when Mr Viner became ill about ten years later and no longer able to earn his living, a testimonial collection was organized by a committee of the NSPS and raised £70.

So Henry Eckford’s form, the third of this ruffled trio, said to be a hooded form and one of the largest flowered of its type, and one which consistently produced four flowers per stem, he bought from Mr Viner – and then sold it not as ‘Nellie Viner’ but as ‘Countess Spencer’. Strangely, ‘Nellie Viner’ is still grown today but seems more like an Unwin type, or a very slightly waved Grandiflora, than an early Spencer.

It seems extraordinary that this break should occur in three different places, originating in two different ways (though both involving ‘Prima Donna’), and resulting in three different forms at almost exactly the same time. The Unwin type was between the Grandiflora type and ‘Countess Spencer’ both in size and the degree of waviness of the standards. But there was also one other, perhaps more crucial, difference. Before W. J. Unwin released his variety, he ensured that it was fixed and uniform. So by contrast with ‘Countess Spencer’, growers could be sure of the result of sowing seed of ‘Gladys Unwin’ rather than be faced with the unpredictability of ‘Countess Spencer’. It was this dependability which was the foundation for the creation, in 1903, of the company which became the Unwins Seeds of today, still the leading retailer of sweet peas and trading from the same site on which his ‘Prima Donna’ sweet peas were grown.

After the revolution

There followed a great burst of enthusiasm for sweet peas, especially the Spencer type. For some years both the Grandifloras and the Spencer types continued to be developed; new Spencers arose through back-crossing ‘Countess Spencer’ on to Grandifloras of various colours to increase the colour range of Spencers and then by making crosses between Spencers, and also isolating sports.

In 1911 Lord Northcliffe, owner of the Daily Mail, offered a prize of £1,000 for the finest bunch of 12 spikes of sweet peas; entries were restricted to amateurs who employed not more than a single gardener. At the competition at the Crystal Palace in London, 35,000 entries were received. An expert committee of ten sweet pea growers narrowed the entries first to 10,000 and selected 1,003 for awards. The first prize went to Mrs Denholm Fraser of Kelso in Scotland; her husband, the Reverend D. Denholm Fraser, won third prize with blooms from the same garden – and it was he, not his wife, who published a small book capitalizing on his success.

The new Spencer types soon dominated although Grandifloras continued to be raised as the enthusiasm for sweet peas continued. Between 1921 and 1925, over 600 stocks of sweet peas were trialled at the RHS garden at Wisley. With, understandably, insufficient space to grow them all in one season the stocks were divided into colour groups and a different range grown each year. This number included almost no Cupids and no early flowering sorts. Later, in 1931, a staggering 321 stocks were grown for trial. At this time, to avoid the confusion occasioned by the constant influx of new introductions, the NSPS issued an annual List of Too-much Alike Varieties; such a list would still be useful today.

In the United States, new types were developed: some were more tolerant of the hot summers that both the Spencers and Grandifloras found uncomfortable, others were developed for cropping as cut flowers under glass.

Since the Spencers took over, breeders around the world have introduced varieties with larger flowers, flowers in a better and more consistent form, flowers with greater substance to the petals, flowers better placed on the stem for exhibition, and more consistent in producing four flowers per stem even in less than careful culture. Vigour has been improved and contemporary varieties grow to almost twice the height of early, pre-Spencer sweet peas in even average cultural conditions. Colours too have improved, from the purest white through every shade of pink to orange and red, plus many shades of lavender and blue through to almost black, these colours combining with the other attributes to constantly improve the flower.

There is still a continuous stream of new introductions from both amateur and professional breeders. One of the factors driving the introduction of new varieties is that each of the major retail seed companies, and the sweet pea specialists, likes to have its own unique varieties; inevitably this leads to what non-specialists at least view as duplication.

Since the arrival of the Spencers, other classes of sweet peas that have emerged include the early-flowering varieties such as the Cuthbertsons, important in many regions of the United States as they flower before the summer heat becomes too intense; productive cut-flower types like the Royals, the tendril-free types like Snoopea, Supersnoop and Explorer and the more recent New Century Series; a range of Intermediate types reaching about 90cm/3ft height, in particular the Jet Set Series; Multiflora types with up to 11, but more often six to eight, flowers on a stem like the Early Multiflora Giganteas and Galaxys. And now there is a resurgence of interest in dwarf types derived from Cupids, originally introduced in 1898.

Classic larger-flowered waved varieties that followed the original ‘Countess Spencer’ and ‘Gladys Unwin’ include ‘Mrs C. Kay’, ‘Noel Sutton’, ‘Nora Holman’, ‘Mrs R. Bolton’, ‘Mrs Bernard Jones’, ‘Jilly’, ‘Midnight’, ‘Windsor’, ‘Leamington’, ‘Southampton’ and more. And after many years in which the Grandifloras were largely neglected, since the 1980s interest in this group has revived and the original varieties, or replicas of them, have been reintroduced. Now a number of breeders including Peter Grayson, Unwins and E. W. King are again introducing new varieties in the Grandiflora style.

In modern times

The development of sweet peas in modern times can be conveniently split into three strands. In Britain, breeding has been almost exclusively in the Spencer sweet peas, with some interest in dwarfer types and a recent revival in Grandifloras; in the United States there has been a greater interest in semi-dwarf or intermediate types and on tall types for commercial production and varieties which tolerate the summer heat. In New Zealand, thanks to one man, Dr Keith Hammett, bicolours, ‘fancy’ kinds and the search for a yellow sweet pea have predominated.

In Britain the development of Spencer types has been driven partly by tradition, partly by the conservative nature of the British gardening public and partly by exhibitors who, until recently, have tended to drive the awards process. This has resulted in the virtues of long strong stems, limited number of flowers on the stem, placement of flowers on the stem, the form of flowers, and response to cordon culture taking precedence over qualities such as long flowering season, many flowers on a stem, tolerance of failure to dead-head, long vase-life and long stems for cutting on semi-dwarf plants.

In recent years two other groups have been developed in Britain: Grandifloras and dwarf types. Peter Grayson has rescued, popularized and made available many old original Grandifloras and has also raised new varieties in the old style. Unwins Seeds and E. W. King have also raised new Grandifloras and some of these are very effective garden plants.

At the same time, E. W. King was a pioneer of the semi-dwarf, tendril-free type with Snoopea and has recently revived this group with their New Century Constellation Series. ‘Pink Cupid’ has also been revived and has proved popular as a garden centre plant, seedlings being sold in striking pink pots. Tony Hender of British plant breeders Floranova and then Seedlynx has gone on to develop a modern series of Cupid types. Amateur breeder Andrew Beane is also working on this group, with particular emphasis on striped dwarfs, as seen in his Pinocchio Series. Dwarf types are also coming into Western Europe from Russia, winning awards and being made available in the West.

Tall tendril-free types have recently made a reappearance. Harvey Albutt’s ‘Astronaut’ won an AM at Wisley in 1989, then Thompson & Morgan developed his work into a consistent range of colours released as a mixture, ‘Astronaut Mixed’, in 2002. It remains to be seen if the flowers are of sufficiently high quality to please exhibitors, for it is exhibitors who routinely remove tendrils and so would perhaps appreciate naturally tendril-free plants. Oddly, Peter Grayson introduced a pale blue, tall, tendril-free type called ‘Spaceman’ in 1997.

In the United States, the emphasis has been different. The necessity to develop varieties which cope with the harsh summer climate of many areas has led to the creation of series like the Cuthbertsons which better tolerate summer heat and Winter Elegance which flower more quickly from seed so can mature in the short period between spring thaw and summer heat.