13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

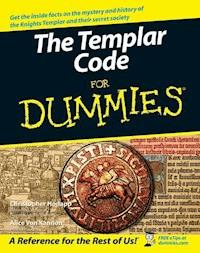

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A captivating look into the medieval (and modern day) society of the Knights Templar The Templar Code is more than an intriguing cipher or a mysterious symbol - it's the Code by which the Knights Templar lived and died, the Code that bound them together in secrecy, and the Code that inspired them to nearly superhuman feats of courage and endurance.If you know a little or a lot about the Templars, read The Da Vinci Code (or saw the movie), or are a Catholic wanting to know the church's official stance on the Templars, you're in the right place. The Templar Code For Dummiesreveals the meaning behind the cryptic codes and secret rituals of the medieval brotherhood of warrior monks known as the Knights Templar. With this comprehensive and user-friendly guide, you'll learn: * What part the Knights Templar played in the Crusades * How the Order started as protectors of pilgrims * The myths of the Holy Grail, and how they're connected to the Knights Templar * How the Knights Templar rose so high and fell so far * How the fraternity of the Freemasons' modern Order of Knights Templar figures in * Why the Catholic Church didn't like Dan Brown's version of the Templar story * The Catholic Church's relationship with women and the connection with the Knights * Why the Knights Templar still captures our imagination today * Whether the Knights had a real part to play in historic events such as the French Revolution and the American Civil War You can learn about all of that and so much more, including sites where the Holy Grail might actually be, what you can't miss if you're sightseeing in Templar territory, and potential hiding places of Templar treasures. Get your copy of The Templar Code For Dummiesto learn more about the fascinating history of this intriguing group of knights.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 717

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

The Templar Code For Dummies

by Christopher Hodapp and Alice Von Kannon

The Templar Code For Dummies®

Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2007 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. The fact that an organization or Website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read.

For general information on our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002.

For technical support, please visit www.wiley.com/techsupport.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2007926386

ISBN: 978-0-470-12765-0

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

About the Authors

Christopher Hodapp is a Freemason and a member of the Masonic Order of the Knights Templar. He is the author of Solomon’s Builders: Freemasons, Founding Fathers and the Secrets of Washington, D.C., and his first book, Freemasons For Dummies, has quickly become the most popular modern guide to the ancient and accepted fraternity of Freemasonry. In 2006, he received the Duane E. Anderson Excellence in Masonic Education Award from the Grand Lodge of Minnesota, and the Distinguished Service Award from the Grand Commandery of the Knights Templar of Indiana. He has written for Masonic Magazine, Templar History Magazine, The Philalethes Magazine, and The Indiana Freemason, and he is a monthly columnist for Texas Home Gardener. Chris has spent more than 20 years as a commercial filmmaker.

Alice Von Kannon has been an advertising executive, a teacher, a writer, and even a greedy and villainous landlord. She studied film production at Los Angeles Valley Community College and history at California State University, Northridge, and she has worked for many years as a writer and broadcast producer. Alice has traveled widely in Europe and the Middle East and has written extensively on the subject of the Barbary Wars and the birth of the U.S. Navy. She is a member of the Order of the Grail, the fraternal body of the International College of Esoteric Studies. A history junkie beyond the help of intervention since the age of 14, her recent studies of Near Eastern religious cults and sects led to this, her first For Dummies book.

Hodapp and Von Kannon both live in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Dedication

For Steven L. Harris (1954–1999)

“He was a truly perfect, gentle knight.”

Authors’ Acknowledgments

Our deepest appreciation goes to the many friends and authors who unselfishly shared their knowledge and love of the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon with us.

To Stephen Dafoe, author of numerous books about the Order, and the editor of Templar History Magazine, who graciously acted as the Technical Editor of this volume.

To Rabbi Arnold Bienstock of Congregation Shaarey Tefilla in Indianapolis for his indispensable help in deciphering Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic; to Father James Bonke and the Catholic Center of Indianapolis; and especially to Most Reverend Phillip A. Garver of l’Eglise Gnostique Catholique Apostolique for his incredible knowledge of Gnosticism, Martinism, Catharism, and all things esoteric.

To Nathan Brindle, Jim Dillman, Jeffrey Naylor, Eric Schmitz, R. J. Hayes and all the “Knights of the North” for their constant support and input.

To Andy Jackson, Larry Kaminsky and especially the Sir Knights of Raper Commandery No. 1, Knights Templar of Indiana.

To Tracy Boggier at Wiley Publishing for being a tireless champion of this book through a long and circuitous route to completion; to our indefatigable editor Elizabeth Kuball for bravely withstanding the onslaught of two of us this time; to Jack Bussell for his cheerful assistance, usually with absolutely no notice whatsoever; and to the entire For Dummies team that works behind the scenes to make this process simple.

And finally, to Norma Winkler, who has been a boundless source of help, support, confidence, and love.

Publisher’s Acknowledgments

We’re proud of this book; please send us your comments through our Dummies online registration form located at www.dummies.com/register/.

Some of the people who helped bring this book to market include the following:

Acquisitions, Editorial, and Media Development

Project Editor: Elizabeth Kuball

Acquisitions Editor: Tracy Boggier

Copy Editor: Elizabeth Kuball

Technical Editor: Stephen Dafoe

Editorial Manager: Michelle Hacker

Consumer Editorial Supervisor and Reprint Editor: Carmen Krikorian

Editorial Assistants: Erin Calligan Mooney, Joe Niesen, Leeann Harney, David Lutton

Cartoons: Rich Tennant (www.the5thwave.com)

Composition Services

Project Coordinator: Lynsey Osborn

Layout and Graphics: Carl Byers, Joyce Haughey, Shane Johnson, Laura Pence

Anniversary Logo Design: Richard Pacifico

Proofreader: Aptara

Indexer: Aptara

Publishing and Editorial for Consumer Dummies

Diane Graves Steele, Vice President and Publisher, Consumer Dummies

Joyce Pepple, Acquisitions Director, Consumer Dummies

Kristin A. Cocks, Product Development Director, Consumer Dummies

Michael Spring, Vice President and Publisher, Travel

Kelly Regan, Editorial Director, Travel

Publishing for Technology Dummies

Andy Cummings, Vice President and Publisher, Dummies Technology/General User

Composition Services

Gerry Fahey, Vice President of Production Services

Debbie Stailey, Director of Composition Services

Contents

Title

Introduction

About This Book

Conventions Used in This Book

What You’re Not to Read

Foolish Assumptions

How This Book Is Organized

Icons Used in This Book

Where to Go from Here

Part I : The Knights Templar and the Crusades

Chapter 1: Defining the Templar Code

Knights, Grails, Codes, Leonardo da Vinci, and How They All Collide

Warrior Monks: Their Purpose

Templars in Battle

Betrayed, Excommunicated, and Hunted

Templars in the 21st Century

Chapter 2: A Crash Course in Crusading

Getting a Handle on the Crusades

A Snapshot of the 11th Century

The First Crusade: A Cry for Help, a Call to Arms

Let’s Give It Another Shot: The Second Crusade

The Third Crusade

The Final Curtain

Chapter 3: The Rise of the Knights Templar

The Perils of Pilgrimage

A New Knighthood

A Simple Mission Creates a Powerful Institution

The Explosion of the Order

International Bankers

Imitation, the Sincerest Form of Flattery

Up Where the Air Is Thin: The Templars Reach Their Zenith

Part II : A Different Kind of Knighthood

Chapter 4: Living in a Templar World

A Standard Unlike Any Other

Who’s in Charge around Here?

The Templar Commandery: Medieval Fortress and City

Symbols of the Templars

Chapter 5: The Poor Knights Crash and Burn: The Fall of the Templars

The Seeds of the Fall in the Nature of the Order

Cracks in the Armor

The Treacherous Kingdom of Jerusalem

Dark Clouds Converge over France

The Accusations

The Confessions

The End

Chapter 6: Cold Case Files: The Evidence against the Templars

The Chief Accuser

Opening Move: An Illegal Arrest

The Charge Sheet

Blowing Away the Charges, One by One

The Pope Knuckles Under

Secretly Absolved

Part III : After the Fall of the Templars

Chapter 7: Templars Survive in Legend and in Fact

The Templar Fleet

Talking Treasure

The Scottish Legends

Templars Part Deux: Return of the Living Knights

The Greatest Templar Myths

The Templars Survived!

Chapter 8: “Born in Blood”: Freemasonry and the Templars

The Masonic Fraternity: Who Freemasons Are and What They Believe

Identifying the Possible Templar Origins of Freemasonry

The Masonic Knights Templar and Where They Came From

Chapter 9: Modern-Day Templars

Modern Templar Orders

Knights But Not Templars

Teetotaling Templars of Temperance

Part IV : Templars and the Grail

Chapter 10: The Templars and the Quest for the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail: A Ten-Century Quest

The Quest Begins

The Templars and the Grail

The Real Grail?

Chapter 11: The 21st Century Dawns with a New Grail Myth

Holy Couple: The Search for the Bloodline of Christ

Holy Blood, Holy Grail: The Legend Rediscovered

Part V : Squaring Off: The Church versus the Gospel According to Dan Brown

Chapter 12: Templars and The Da Vinci Code

The Secret Societies of Dan Brown

Leonardo da Vinci and His Last Supper

Chapter 13: The Suppression of the “Feminine Divine”: Truth or Feminist Fiction?

Defining Divine Femininity

Mary’s Marriage: Pros and Cons

Goddess Worship and the Sacred Feminine: Do We Really Want It Back Again?

The Catholic Church’s Relationship with Women

Chapter 14: Getting Our Acts Together: Constantine and the Council of Nicaea

Fiction, History, and the Early Church

What Boring Old History Books Say

Part VI : The Part of Tens

Chapter 15: Ten Candidates for the Site of the Holy Grail

Glastonbury Tor, England

Hawkstone Park (Shropshire, England)

Takt-i-Taqdis, Iran

The Santo Caliz (Valencia, Spain)

Sacro Catino (Genoa, Italy)

Rosslyn Chapel (Roslin, Scotland)

Wewelsburg Castle (Buren, Germany)

Montségur, France

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Castle Stalker (Argyll, Scotland)

Chapter 16: Ten Absolutely Must-See Templar Sites

Where It All Began: Temple Mount (Jerusalem, Israel)

Temple Church (London, England)

Royston Cave (Hertfordshire, England)

Rosslyn Chapel (Roslin, Scotland)

Kilmartin Church (Argyll, Scotland)

Chinon Castle (Chinon, France)

Templar Villages (Aveyron, France)

Tomar Castle (Tomar, Portugal)

Domus Templi — The Spanish Route of the Templars (Aragon, Spain)

Where It Ended: ˆIsle de la Cité (Paris, France)

Chapter 17: Ten Places That May Be Hiding the Templar Treasure

Rosslyn Chapel (Roslin, Scotland)

Oak Island Money Pit (Nova Scotia, Canada)

Temple Bruer (Lincolnshire, England)

Hertfordshire, England

Bornholm Island, Denmark

Rennes-le-Château, France

Château de Gisors (Normandy, France)

Switzerland

Trinity Church (New York City)

Washington D.C.’s Rosslyn Chapel

: Further Reading

Introduction

You can tell a lunatic by the liberties he takes with common sense, by his flashes of inspiration, and by the fact that sooner or later he brings up the Templars.

—Umberto Eco

Last October, the two of us received some happy news; after a long process of outlining, cutting, pasting, re-outlining, meetings, major changes, and more meetings, our editor called to say that victory was ours. This somewhat unusual project had made it into the list for 2007; in fact, it would be out by June. We would be doing a project we cared about a great deal, The Templar Code For Dummies. Any author will tell you that this is always a thrill. But the next piece of news was a little unnerving. The official launch date for the project had been set for the following Friday, which happened to be Friday, October 13th.

For one brief moment, a chill of premonition slithered down our backs, like ice cubes at a frat-house party. After a few seconds of silence, we did what many people do when they have an uncomfortable moment of premonition; we both burst out laughing. It did help the shiver.

The chill we felt wasn’t because we’re particularly superstitious, at least, no more so than anyone else. It was something far more disconcerting than mere superstition. Because for anyone who knows the lore of the Knights Templar, Friday, October 13, 1307, was the date that the Order was rounded up all across France in one single day, by order of the French king, Phillip IV, to be indicted on various charges of heresy. In fact, this is sort of superstition in reverse, because the reason that Friday the 13th is considered an unlucky day, so the legend goes, is because of what happened to the Templars on that fateful date, seven centuries ago. Whistling in the cemetery, we decided it was the perfect launch date for the book.

That particular Friday was the 699th anniversary. By the time this book is on the shelves, it will be precisely 700 years since the Knights Templar were arrested, and seven centuries haven’t dimmed the fascination people have with this mysterious, courageous, and singular brotherhood of knights.

What is known for certain about the Knights Templar is a story with a larger-than-life aura of myth, that finished in an abrupt and almost unbelievable tragedy. Founded in A.D. 1119 by nine crusading French knights, the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (known as the Knights Templar) shot across the political landscape like a meteor, vaulting from obscure guardians of pilgrims in Jerusalem to the most powerful and influential force of their age. They were fierce warriors, devout monks, and international bankers. Within half a century of their birth, they were men who walked with kings and advised popes, brokered treaties, and built castles and preceptories on a massive scale. Then, even more inexplicable than their rise came their fall, a harrowing plunge into arrest, trial, flight, and execution that shocked the medieval world, both East and West. The charges against them of heresy and sodomy were equally shocking, and are still debated by historians today.

In fact, theories about the Templars are hotter today than ever before. Historians, researchers, wishful thinkers, and dreamers have claimed that the Templars lived on after their destruction, placing them in Portugal, Scotland, Switzerland, Nova Scotia, and Massachusetts. They are alleged to have sailed pirate ships, founded banking dynasties, and given birth to the Freemasons. Their explorations in the Holy Land have led to speculation that they found the Ark of the Covenant, the True Cross of Christ’s crucifixion, the head of John the Baptist, the Spear of Destiny, and the Holy Grail. They have alternately been described as pious guardians of the most sacred secrets of Christianity, and as heretical practitioners of occult and satanic rites. And more than one suicidal doomsday cult has claimed to be descended from the Templars, living in wait for the Intergalactic Grand Master’s mother ship to enter low-earth orbit and beam them aboard.

In 2003, an author named Dan Brown published a modest sequel to a moderately successful mystery entitled Angels & Demons. Little did he know that he was handling fissionable material. The Da Vinci Code has sold more than 60 million copies in 44 languages, and is the eighth most popular book ever published. In it, Brown told the tale of the “true” nature of the legend of the Holy Grail. If you’re one of the seven or eight people left on earth who haven’t read it yet, allow us to spoil the ending for you. According to Brown, the Grail was not some humble cup used by Christ at the Last Supper, or even a golden, jewel-encrusted chalice. It was the bloodline of Jesus, a child born to Mary Magdalene from a union with Christ. The book tells of a mysterious organization that was created to keep the secret, and to protect the offspring of Christ and Mary down through the centuries. And that group, through a succession of plot twists, was — you guessed it — the Knights Templar.

Dan Brown undoubtedly set out to tell a good story, but he couldn’t possibly have known that he was writing what would become a worldwide phenomenon. How could he have known that his book would cause millions of people to reexamine their own beliefs and those of their neighbors, inspiring thousands to make pilgrimages to the sites of his book in France and the United Kingdom, in search of a sign or symbol that would reveal some hidden truth to them? He might not have intended it, but, whether by chance or fate, that’s exactly what happened. And curiously, in spite of what many alarmed religious leaders feared, the result has been a greater interest in the origins of Christianity, and a whole world of readers whose faith seems to have been strengthened by what they’ve found.

Brown, like so many others, looked at the Knights Templar and was intrigued by what he saw. The unanswered mysteries and outlandish legends surrounding them didn’t just spring out of nowhere, or even out of Mr. Brown’s fertile imagination. The Templars have been a pillar of Western mythology for centuries, and there’s no end in sight for the world’s obsession with the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon.

About This Book

We wrote this book to assemble the vast, outlandish, popular, and confusing lore of the Knights Templar into one convenient volume. The first four parts of the book strictly tell the Templar story; their rise, their fall, and the forces at work in the world that gave them birth. If you first encountered this stuff in The Da Vinci Code, you can go straight to Part V; that entire part is devoted to the questions raised by the novel, including the bloodline of Christ, the “sacred feminine,” and the mysterious relationship between those concepts and the Templars. It’s a unique approach, but it should give you a great overview of the Templars and their world, as well as a definite leg up at the office holiday party when somebody wants to talk your arm off about the Black Madonna Cult or the Council of Nicaea.

We’re both writers, both history fanatics, and both obsessed with the Knights Templar. While other people may loll about, wasting their vacations broiling on the beaches of Cancun or falling down the ski slopes of Aspen, history cranks like us spend our free time taking off every year for the backcountry of France and Britain, Portugal, and Turkey, up at dawn every day to strap on a backpack and go sweat our way up another ruin. We know how to have a good time. Who wants to spend a vacation lolling on the beach with an umbrella drink in his hand?

We’re hoping that in this book, all that sweat paid off. Together we’ve stood in the prison cell of Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, reading the messages scratched onto the walls by the imprisoned knights. And together we’ve stood on the Îsle de la Cité in the shadow of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, where de Molay was burned at the stake for the amusement of the crowd that was, to the vindictive king’s disappointment, sullen rather than boisterous.

Generally, people in the 14th century enjoyed a good burning or hanging or quartering, but no one was indulging in any satisfaction on that tragic day. The Templars had been the most formidable knights of Europe, brave warriors as well as monks sworn to a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. No one gave up more for the sake of his faith than a Knight Templar. Consequently, the Poor Knights, as they were sometimes called, had the respect of the entire Christian world, and even many in the enemy camp. When the brilliant soldier Saladin won back the Holy Land from the Crusaders, the prisoners he took who were to be beheaded at once, without question of ransom or the slave market, were the Templars. As far as Saladin was concerned, they were just too dangerous an enemy to be left alive. And never once did a Templar knight beg for his life. After the disastrous Battle of Hattin, they queued up in their hundreds to be slaughtered, each calmly waiting his turn.

Everyone knew the legends of their almost foolhardy courage, and everyone knew what the Templars had sacrificed in order to secure the Holy Land for the sake of Christian pilgrims, so that the souls of the men and women on this journey could be saved from purgatory or damnation. In fact, one particular biblical quote from John 15:13 was something of an unofficial motto for the Templars: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” The general consensus of the somber crowd on that bleak execution day in 1314 has been the general consensus of most people ever since: that the Templars were getting a very raw deal, whether they had fallen victim to some Eastern heresy or not.

For us, ever since that prophetic launch date, we’ve had the feeling that the martyred de Molay could be looking over our shoulders, which made for two very nervous writers. More than anything else, we wanted to get it right. We think we have.

Conventions Used in This Book

We don’t use many conventions in this book — why use conventions when you’re talking about such an unconventional group of guys? — but we do use a couple:

Any time we define a term for you, we throw some italic on it and put the definition nearby, often in parentheses. (We sometimes use italic for emphasis, too, because our editor won’t let us type in all caps — something about sounding hostile.)

Web addresses and e-mail addresses appear in a funky font called monofont. It’s there so you can easily tell what to type in your Web browser and what to leave out.

When this book was printed, some Web addresses may have needed to break across two lines of text. If that happened, rest assured that we haven’t put in any extra characters (such as hyphens) to indicate the break. So, when using one of these Web addresses, just type in exactly what you see in this book, pretending as though the line break doesn’t exist. And if you do see a hyphen in a Web address, that means you’re supposed to type it.

What You’re Not to Read

You don’t actually have to read anything in this book — we won’t test you on it, we swear — but we know you won’t be able to resist turning the page. When you do, you can safely skip anything marked by the Technical Stuff icon (see “Icons Used in This Book” for more on that). You can also skip sidebars (text in gray boxes), because they’re not critical to your understanding of the subject at hand.

Foolish Assumptions

The Templar Code For Dummies was written for a lot of different people, but we make a few superficial assumptions about you, without even knowing you or asking your relatives about your most embarrassing moments. With luck, one of these descriptions fits you like a chain-mail gauntlet:

You know nothing about the Templars. If so, the whole story is here: the Crusades from which they emerged; the Christian society back home in Europe and the strange combination of religions and cultures they were surrounded by in the Holy Land; their skyrocketing fame among the movers and shakers in Rome and the capitals of the world; their lavish wealth and their creation of the banking business; their mysterious reputation as the “Grail knights”; and their abrupt fall and destruction.

You know a little about the Templars. If you’ve already studied some about the knights, this book will put it all in perspective for you. It covers the facts and the legends, from the plausible to the downright preposterous.

You first heard about this stuff in The Da Vinci Code.The Templar Code For Dummies is the book you need to make sense of Dan Brown’s connections between the Templars, the Priory of Sion, the Holy Grail, and the sacred feminine. As good as The Da Vinci Code is, what Brown wrote wasn’t a new theory — it’s been around for a while — and he left a lot out of the whole picture. In this book, we explore what the connections really are and where they might have come from.

You are either a Christian or an interested bystander. Especially if you’re a Catholic, or just wonder what they say about all this hullabaloo, we clue you in on the Church’s position on the Templars, Constantine, Opus Dei, celibacy, Black Madonnas, and killer albinos.

You are a Freemason. If so, this book is an essential. The fraternity of Freemasons has a modern Order of Knights Templar, and though they don’t profess a direct descent from the original 12th-century knights, an awful lot of claims have been made over the years about the Templar origins of the Masons. There’s more to the Templars than what the Masonic version says, and in this book we clear up the confusion.

How This Book Is Organized

If you sped right past the Table of Contents without bothering to signal, go back and take a look. You’ll see this book is divided into six easily digestible slices. Feel free to read them in any order. We don’t care. Really. Here’s what you’ll find inside.

Part I: The Knights Templar and the Crusades

You can’t tell the players without a program, and you can’t understand the Knights Templar without knowing a little bit about the Crusades. In this part, we give you the overall lay of the Templar landscape. In Chapter 1, we set out the road map that leads from Jesus and Mary Magdalene to the Templars and the Holy Grail. In Chapter 2, we cram hundreds of years of crusading history into one densely packed, whirlwind tour of mucking about in the Holy Land. Finally, in Chapter 3, we trace the very beginnings of the Order as protectors of pilgrims, through their incredible rise in power and prestige as the bankers, landlords, and ecclesiastical fat cats of the Christian world.

Part II: A Different Kind of Knighthood

This section is the red meat of the Templar story — who they were, what they became, how they got whacked, and who did it to them. In Chapter 4, we give you a rundown on the harsh daily lives of the men who chose to become these warrior monks. Chapter 5 examines their annihilation just two centuries later by a king, a pope, and possibly their own successes and excesses. Chapter 6 takes a closer look at the accusations against the Order made during their trial, and pieces together the evidence that was used to make the case — from the serious and creepy, to the outlandish and cockamamie.

Part III: After the Fall of the Templars

In this part, we pick up the trail of mythology that followed the destruction of the Templars. Chapter 7 takes a closer look at what we do know about the Templars after their arrest, trial, and convictions, as well as what we think we know. Chapter 8 examines the possibility that the fraternity of Freemasons crawled out of the ashes of the Order, along with taking a peek at the modern-day Masonic Knights Templar. And in Chapter 9, you discover some other, lesser-known groups that claim to be the 21st-century heirs to the Templar legacy.

Part IV: Templars and the Grail

The Knights Templar and the story of the Holy Grail were twin sons of the same mother, born out of the Crusades. This part explores the Grail myths of the West, their connection to the Templars, and the place of the knights in the new Grail-mania brought on by The Da Vinci Code. Chapter 10 goes back to the beginning to examine the very first Grail stories, their links to both Christians and pagans, and how they led to the ideas of chivalry, courtly love, and King Arthur. Chapter 11 discusses the Grail myth of the 21st century, the supposed bloodline of Christ, starting in the B.D.B. (Before Dan Brown) era with the first modern researchers who proposed the startling notion that Jesus had a wife. From there the tale heads to the south of France, to the mysterious hill town of Rennes-le-Château, and to the legends of the Cathars, who play a major role in the Grail stories of the past and present.

Part V: Squaring Off: The Church versus the Gospel According to Dan Brown

If you picked up this book because The Da Vinci Code was the first place you’d ever read about the Templars and you wanted to find out more, you may want to turn to this part first. For every Christian reader who found new interest in the history of his faith, there was another who was upset or angered by Dan Brown’s alternative theories of his alleged “true” story of Christianity. And the Catholic Church wasn’t exactly thrilled with Brown’s version either.

Dan Brown said that his famous novel was a fictional account based in fact, so this part examines the historical claims put forth in The Da Vinci Code. Chapter 12 looks at Dan Brown’s version of the Knights Templar as the warrior wing of the secretive Priory of Sion, their survival, and their ongoing secret mission to protect the bloodline of Christ. Chapter 13 explores Brown’s many assertions about the history of women before and after the Christian era, the Church’s real historical attitude toward women, and some surprising aspects about Christian women and the sacred feminine. Chapter 14 presents the amazing behind-the-scenes politics in the creation of the Bible we know today. We delve into the significance of the Apocryphal biblical books, and the story behind the recently discovered Gnostic Gospels that have caused many to change the entire structure of their faith. We fearlessly tread on the role of celibacy in history and in the Church, and its survival into the present day. We finish with the place of the Knights Templar in the newly emerging picture of Christianity, and the latest theories of Templar influence on the survival of these alternative gospels and the secrets they contain.

Part VI: The Part of Tens

This part of the book cuts to the chase and taunts travelers, tourists, treasure-trove hunters, and tall-tale tellers with tantalizing tidbits and Templar tchotchkes. (Please, make him stop.) Chapter 15 explores ten possible candidates for the location of the Holy Grail. Strap on your backpack, grab your camera, and strike out for the ten must-see Templar sites in Chapter 16. Chapter 17 points you in ten different directions to start hunting for the hiding place of the fabled Templar treasure: long forgotten gospels, secret documents, gold and silver, the fabled Ark of the Covenant, or even the Holy Grail itself.

Icons Used in This Book

You’ll find the following icons lurking in the margins of this book. Beyond just giving you a little scenery to gaze at, they help you find what you’re looking for and navigate the potentially scary parts.

The Grand Master was the head of the Knights Templar, the Mr. Know-It-All of the Order. He was in charge of both military and spiritual matters, and it was a tough job. That’s why he’s wearing a helmet for protection. He helps sort out pesky issues about the Templar origins and rules.

This icon marks key points that are vital to understanding the Crusades, the Templars, the Grail myth, or other truly important topics. Don’t skip these!

This icon highlights stuff like additional data, explanations of obscure rituals and practices, or other information that may interest you, but can be ruthlessly skipped over without missing the important themes of the chapter.

This one points out handy tidbits and topical advice.

This icon alerts you to subjects specifically having to do with topics from works of Dan Brown. If The Da Vinci Code is what piqued your interest in this book, these are the hot topics to look out for.

When it comes to the Templars, there are many conflicting sources of misinformation and fantasy masquerading as history. This little icon alerts you to those tantalizing bits of speculation, romantic wisps of wishful thinking, or burgeoning cartloads of crap.

Where to Go from Here

The best news you’ve heard all day is that this is not like a textbook. The genius of the For Dummies series is that it’s designed so you can come and go as you please. If you want to know it all, get all the hot dates, and find the secrets to cutting in line at the bank, start at the title page and read until you hit the back cover. If you prefer, you can skip chapters that don’t interest you without hurting our feelings. Does the prospect of reading about the Crusades make your head throb like you’re at a Bow Wow concert with your kid sister? If so, skip Chapter 2. Want to know why your grandfather has a sword in the attic that says he’s a Knight Templar, even though he can’t wear armor with his bad knee? Head over to Chapter 8. Want to know where the Holy Grail might be hiding so you can grab a pickax and get right to work chopping through some old church floor? (Don’t get caught.) Go directly to Chapter 15.

Part I

The Knights Templar and the Crusades

In this part . . .

T his part begins, appropriately enough, with a general overview of the Knights Templar — who they were and what they believed in, as well as a condensed version of the symbols, accomplishments, and legacy of the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon.

You can’t tell the story of the Knights Templar without at least a nodding acquaintance with the turbulent period of bloodshed known as the Crusades, so buckle your seat belt for Chapter 2, which is the top-speed, full-blast, high-gear version of the medieval wars in the Holy Land. We start with the Very Big Picture — the battle between the Christian West and the Islamic East — and then narrow down to the Holy Land itself — the prize that both sides were after. Then we zoom in even closer in Chapter 3, to the incidents on the road to Jerusalem that gave birth to the Knights Templar, the most powerful force in Christendom, and how their meteoric rise to the halls of power and the splendor of gold catapulted them to a dizzying height.

Chapter 1

Defining the Templar Code

In This Chapter

Getting your feet wet on the subject of warrior/monks

Following the Templars through the Holy Land

Seeing Templars as bankers, diplomats, and nation builders

Discovering Templar codes

Thus in a wondrous and unique manner they appear gentler than lambs, yet fiercer than lions. I do not know if it would be more appropriate to refer to them as monks or as soldiers, unless perhaps it would be better to recognize them as being both. Indeed they lack neither monastic meekness nor military might. What can we say of this, except that this has been done by the Lord, and it is marvelous in our eyes. These are the picked troops of God, whom he has recruited from the ends of the earth; the valiant men of Israel chosen to guard well and faithfully that tomb which is the bed of the true Solomon, each man sword in hand, and superbly trained to war.

—St. Bernard of Clairvaux, In Praise of the New Knighthood (1136)

In A.D. 1119, the Order of the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon formed in the wake of the First Crusade, and the world had never seen anything quite like them. They were knights, dedicated to the same unwritten, medieval, chivalric code of honor that governed most of these fierce, professional fighting men on horseback throughout Europe and the Holy Land. But they also took the vows of devoutly religious monks, consigning themselves to the same strict code of poverty, chastity, and obedience that governed the brotherhoods of Catholic monks who spent their ascetic lives cloistered in monasteries. These were no mercenaries who fought for money, land, or titles. They were Christ’s devoted warriors, who killed when it was necessary to protect the Holy Land or Christian pilgrims.

The Templars became the darlings of the papacy and the most renowned knights on the battlefields of the Crusades. They grew in wealth and influence and became the bankers of Europe. They were advisors, diplomats, and treasurers. And then, after an existence of just 200 years, they were destroyed, not by infidel warriors on a plain in Palestine, but by a French king and a pliant pope. In the great timeline of history, the Templars came and went in an astonishingly brief blink of an eye. Yet, the mysteries that have always surrounded them have done nothing but circulate and grow for nine centuries.

In this chapter, we give you a quick tour of who the Knights Templar were, and the two seemingly contradictory traditions of war and religion they brought together to create the first Christian order of warrior monks. We also discuss the meanings of the codes they lived by, both the code of behavior that governed their daily lives and the secret codes that became part of their way of doing business.

Knights, Grails, Codes, Leonardo da Vinci, and How They All Collide

Everyone loves a mystery. Agatha Christie wrote 75 successful novels in a career that spanned decades, with estimated total sales of over 100 million. Her stories remain a fixture in the bookstore, as well as in film and television. But Agatha Christie always neatly wrapped up the mystery by the end of the story. The historical mysteries examined in the tale of the Templars are far more complex, and it’s rarely possible to tie them up with a ribbon and pronounce them solved.

Interest in the Templars, the Holy Grail, and various mysteries of the Bible have something in common with lace on dresses or double-breasted suits; over the course of the last couple of centuries, the mania will climb, reach a peak, then recede into the background, consigned to the cutout bin of life, to be picked up, brushed off, and brought to rousing life once more by a new generation with a fresh perspective.

The bare facts are simple. After two centuries of pride and power, the Templars went head to head with the dual forces that would destroy them — the Inquisition, and the man who used it as his chief weapon, Phillip IV, called Phillip the Fair, king of France, whose nickname definitely described his looks and not his ethics.

In the heresy trials that followed, the Templars were often accused of being Cathars, a form of Gnostic Christianity that was deemed a heresy by the Catholic Church. We explain Gnosticism in greater detail in Chapter 14, but speaking simply, the Gnostics were dualists, believing that the world was a place of tension between good and evil, light and darkness. The Templar Code may best be defined in the same way — a dual ethic, with two meanings: the decidedly unspiritual violence of the warrior knights on the one side, contrasted with the devoutly spiritual nature of religious life as monks on the other. The most common image signifying the Templar Knights was that of two Templars, armed for battle and riding the same horse together (see Figure 1-1). It was the perfect shorthand for both their fierceness in fighting, and the vow of poverty they lived by.

Figure 1-1: A statue outside of the London Temple church depicting two Templar Knights on the same horse — symbolizing both poverty and fierceness.

Christopher Hodapp

You’d be hard pressed to find a more important and enduring myth in the Christian West than that of King Arthur, his Table Round, and the quest of his knights for the Holy Grail. The Templars were always another pillar of Western mythology, side by side with the Holy Grail legends. The two fables cross constantly along the way, and the many parallels between the Templars and the story of Arthur and the Grail, the parable of a man’s reach exceeding his grasp, may explain, at least in part, the continuing hold of the noble Templar legend on the Western imagination, seven centuries after the destruction of the Order.

And then Dan Brown wrote a book called The Da Vinci Code, and people’s perceptions of the Knights Templar, and just about everything in their world, changed almost overnight. The Templars were described as sinister gray eminences, dark powers behind the throne, keepers of the true Grail, the most dangerous secret of Christianity. Nowadays, truth can be almost anticlimactic. Yet the truth of the Templars is anything but a bore. It’s a story of the highest in the land brought low by greed and envy, of Crusader knights and Islamic warlords, of secret rituals, torture and self-sacrifice, and mysteries that still beguile the historians of the Middle Ages and beyond.

Right now, we’re living in a time when interest in the Templars is at an all-time high, and the reason for it is the intriguing way that all these mysteries, and many more, weave in and out of one another, touching, drifting apart, and then coming together again: Templars, the Grail, the Gnostic Gospels, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Spear of Destiny, the heresy of Mary Magdalene as the wife of Jesus — they’re all tied to one another, with all the same players, in all the same events. The Templar story begins 900 years ago.

The Temple of Solomon

The origin of the temple that makes up the name of the Templars is King Solomon’s Temple, described in the Old Testament books of 2 Chronicles and 1 Kings. It was believed to have been constructed in approximately 1,000 B.C. by the wise Solomon, son of King David.

The temple was the most magnificent monument to man’s faith constructed during the biblical era. Its innermost sanctuary, the Sanctum Sanctorum, was built to hold the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the sacred words of God — the tablets Moses was given that contained the Ten Commandments. (The temple complex occupied what is known as the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, dominated by the Islamic Dome of the Rock; see the first image in this sidebar). It was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.

A second temple (see the second image in this sidebar) was rebuilt on the same spot by Zerubbabel in 516 B.C. after the Jews had been released by the Babylonians 70 years before. This Temple was of a slightly different design and was extensively renovated and enlarged by King Herod the Great in 19 B.C. (This is the temple that Jesus threw the moneylenders out of, described in Matthew 21.) The Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 70 during the Jewish rebellion.

Israel images / AlamyScala / Art Resource, NY

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon

Yep, that’s the full name of the Knights Templar. This name changes here and there, depending on the translation. Obviously, St. Bernard and the others who gave the order this final moniker wanted to make sure that everything about them but their shoe size was reflected in their title.

The Templars were granted the area of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, former site of King Solomon’s Temple (see the nearby sidebar “The Temple of Solomon”) as their Holy Land headquarters. This is where the term Templar originated.

The Templars soon had a nickname, simply the Order of the Temple. Then later came Knights Templar, as well as White Knights, Poor Knights, and just plain Templars.

Defining knighthood

Templar Knights started life simply as knights. The word knight carries with it so much mythological baggage that it may seem a ridiculous question, but just what is a knight, anyway?

You probably think you know all about knighthood, because you’ve seen Sean Connery, Orlando Bloom, and Heath Ledger each play one. Well, actually, if you have, then you do already know quite a lot. The Hollywood treatment of knighthood and its rituals has been right more often than it’s been wrong, which is an amazing thing from an industry known the world over for its cavalier contempt for historical accuracy.

Roman origins

The concept of knighthood is an old one. The word itself — whether it was knight in English, chevalier in French, or ritter in German — simply means a cavalry warrior, one who did battle from the back of a horse instead of clomping along in the mud with the infantry. In the beginning, this didn’t necessarily make him a person of higher rank than an infantryman. The cavalry warriors of the Roman army were called equitatae, a pretty squishy word that just means “mounted.”

The medieval knight

The cavalry knight of the Middle Ages grew into a powerful force as the centuries passed. And the knight was inseparable from the feudal system in which he lived. As with everything else in Europe, Rome had a hand in the creation of the feudal system. This feudalism, from its very inception, was essentially a contract. The knight and his own vassals made various promises to their lord, to pay taxes or to serve him in wartime for a certain number of days each year, often 40 days, while the lord also made various promises.

Knights were proud and powerful men, with squires and servants, and so on, but their influence shouldn’t be overstated. Where the feudal chain of power was concerned, knights were close to the bottom, at least at first. A knight errant was a knight who had no lands, a little higher than a paid mercenary. For the knight errant, his first goal was to gain lands in battle, and he fought in the hope of being granted a fief by his overlord in gratitude for services rendered. Eventually, this knightly rank and vow of service became hereditary, and with these inherited titles came land and greater privileges.

A strange development in the history of knighthood was that these warriors, who were not necessarily of noble birth or great wealth, were great military leaders. As a result, the nobility became envious of this “lower class” of men, and became knights themselves. Later orders of knights, Templars included, always preferred their knights to be at least the petty nobility to be a part of their groups, to lend them greater prestige. By this time, sons of earls, dukes, and even kings proudly bore the title of knight. Eventually, it made economic sense for the nobility to be knights — it was an expensive way of life to buy horses and equipment, and working slobs didn’t have the kind of leisure hours needed to train themselves for battle.

The decline of the knight

After the fall of Rome, battle tactics changed quite a bit in the following centuries. With the development of body armor, a mounted knight became a far more powerful adversary than a much larger number of men on foot, and knights formed the power core of armies in the way foot soldiers once had. Socially, the feudal system lingered for centuries. But the real end of knighthood, military knighthood, came with changing military tactics. More than any other factor, the development of greater speed, power, and accuracy in the bow and arrow would spell the doom of the knight in the field.

By the late 16th century and the development of field artillery, the warrior knight of the Middle Ages was already more of a mythic figure than an effective force on the battlefield. Though some still rode horses and wore armor, and hereditary knighthood continued to be passed from father to son, the legendary knights of the crusading period were already the stuff of moldy tapestries and mythic tales.

Flipping the bird: The sign of victory

Like many coarse and vulgar Americanisms that have gone worldwide, if you travel in England, you’ll see people from cabbies to pub brawlers use a classic American gesture of defiance — arm extended, fist closed, middle finger pointing in solitary contempt into the air. But this is a relatively recent development, the U.S. pollution of a much funnier British hand gesture. As late as The Benny Hill Show or the terrifically funny Carry On movies of the 1960s, you see the British using their own, centuries-old method of “flicking thine enemy the royal bird.” The English version looked more like a victory sign — once more, arm extended, fist in the air, but with two fingers up, the index and middle finger. This gesture has a noble, if mythical, history. In several battles with the French, the British military discovered that their most valuable force against a superior number of mounted knights was their skilled archers. The technology of armor-piercing arrows was getting better all the time. And so, the government unleashed a program of training the peasantry in archery, with prizes awarded, clubs formed, and such, to try to make it fun, as well as a point of national pride. They succeeded. All across England, at dusk on the village green after the day’s work was done, men practiced their archery, every day. At the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, British archers as a military force reached their peak of rapid fire, power, and skill, bringing down thousands of French mounted knights and winning a battle in which they had been greatly outnumbered.

Consequently, the French cooked up a counteroffensive. Whenever a British foot soldier was captured in battle, the first two fingers of his right hand were amputated, so that he could never again draw a bow. For centuries afterward, when British soldiers wanted to razz the enemy, they would raise their two fingers high up into the air, with a “you didn’t get mine, you froggy so-and-so” attitude, usually accompanied by colorful raspberries and shouts about the morals of the French soldiers’ mothers. During the dark days of the Blitz in World War II, when Hitler’s rockets rained down on London, killing thousands, it became, once more, a treasured symbol of British defiance. That’s the legend, anyway.

Defining monasticism

Monasticism grew out of an idea as old as knighthood. In even the most ancient pagan faiths, there were legends of monks and hermits, men who separated themselves from society, living in caves or the out of doors, in order to achieve a closer relationship to the spiritual. Despite the fact that monks live in communities, the word monasticism comes from the Greek word monachos, which means “living alone,” in reference to these lone hermits who inspired it. Not just Christianity, but Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Jainism (a peaceful Indian sect of ascetics) all practice monasticism. Organized Christian monasticism goes back at least as far as the fourth century. As the ideal picked up speed, it formed into the more common orders we know today — the Benedictines, the Franciscans, the Dominicans, and so on. But the name of the game was the same for all. Though each order had its own character, patron saint, and principle type of devotion (as in aiding the sick, teaching, or being strictly a “contemplative” order, devoted to prayer), all monks lived a bare and vigorous existence.

Both jobs — knight and monk — were definitely enough to keep you busy. They were also about as opposite in their goals, actions, and beliefs as two occupations could be; monks were not even allowed to carry a weapon, no matter how dangerous was the pagan territory they were sent into to spread the gospel to the barbarians, mostly the descendants of the Visigoths and Huns who’d brought down the might of Rome. Nevertheless, rather than fight, monks were expected to die for their faith if necessary. Moreover, they were expected to die well, because first impressions are so important where nonbelievers are concerned.

Warrior Monks: Their Purpose

What made the Knights Templar unique in history was that they decided to take on both obligations, knight and monk. They would be warriors for God, sworn to a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. It was a startlingly new concept to the Christian West, and there was a great deal of resistance to it at first. But the idea seized the imagination of the charismatic figure of the Cistercian Order, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who pushed it through the ecclesiastical bureaucracy.

And so, by papal command, the Order of the Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon was born. They were also given, in a series of papal bulls, powers and privileges that had never before been extended to any single arm of the Church. (A papal bull is an official statement-of-position document issued by a pope, named for the bulla, or round wax seal, affixed to the document.) The Templars were, in effect, now answerable only to the pope in everything they did. But, like most things in life, that power came with a price.

In the recent wave of books and movies featuring Templars, one thing seems to come across above all else: They were loaded. Everyone seems to know that there’s a lost Templar treasure out there. But this had nothing to do with the way a Knight Templar lived in the day to day. In the Middle Ages, faith was woven into the fabric of life in a way that would be nearly impossible to explain to the modern, secular mind. Only the life of a person in a religious cult would come close, and even that is a flawed comparison. In this medieval world of faith, laymen gave up all sorts of things for the sake of their belief in God. Monks, priests, and nuns gave up a great deal more: love, marriage, children, freedom, luxury, and any sort of self-indulgence, down to the smallest, most inconsequential comforts.

But few gave up more for the sake of his faith than a Knight Templar. We discuss the daily life of a Templar in more detail in Chapter 4, but for the time being, suffice it to say that the wealth belonged to the order and most decidedly not to any individual knight. At that time, the holiest of men and women lived a life of asceticism, a constant state of self-denial. The quantity and quality of food was extremely limited; the Templars were allowed the luxury of meat three times a week on the theory that, as fighting men, they needed it. But eating it wasn’t much fun — for monks, nuns, and Templars, meals were taken in silence, generally while scripture was being read. The monastic day was roughly divided into four-hour sections, called the Liturgical Hours, or the divine office, the seven Catholic hours being Matins, Lauds, Vespers, Terce, Sext, None, and Compline. Each one represented another trip to chapel, for Mass or prayers or readings from Scripture and the Church fathers. Even a good night’s sleep was interrupted for a trip to the chapel to pray. No personal possessions were allowed under any circumstances; all that these people owned were the clothes on their back. Visits to and from family were discouraged, because it tied a person to his old life. A Templar was even expected to have light in his private chamber at all times, to prevent even the accusation of hanky-panky.

Some other monastic orders had stricter rules for daily life, but they certainly weren’t risking their lives in battle. Along with giving up a wife and children, possessions, and freedom, Templars were also expected to give up their lives fighting for the faith. A Templar was not allowed to retire from the battlefield, even to regroup, unless the enemy had a three-to-one superiority. Whenever Crusader knights went into battle, the highest casualty rates were always among the Templars.

There were perks, of course, here and there, particularly for the officers of a commandery. In the Holy Land, there were few higher in the new kingdom of Jerusalem than the Grand Master of the Knights Templar. He advised the court in all matters — foreign, domestic, and military. The Templars walked with popes and kings, their courage and their honesty never questioned, which is what made their breakneck fall from grace so much more shocking.

A vow of nine crusader knights

We cover the concept of pilgrimage in more detail in Chapter 2. Here, we must explain one thing: The other two major monotheistic faiths — Judaism and Islam — both practiced the obligation of pilgrimage to holy places. Although pilgrimage isn’t written down in Christian ritual, it was no less important to medieval believers. Almost since the beginning, pilgrimage was considered a way to save a soul in peril. And Jerusalem was ground zero for Christians, the holiest of holies. Medieval mapmakers referred to it as the “navel of the earth,” the center of all things. When the Holy Land was in the hands of the Christian Byzantine Empire, this was no problem. The roads were hazardous, yet people generally got there alive. But when the property was stolen by waves of Islamic Seljuq Turks in the 11th century, pilgrims were risking life and limb to get there. They were attacked on the road constantly, not only by the Turks, but by various unsavory bands of thieves and cutthroats. Going in groups didn’t help; the brigands were a lot tougher than the people who had come to pray at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

After the First Crusade, Jerusalem was back in the hands of Christians for the first time in four centuries. But afterward, the majority of the knights went home, back to their feudal obligations. There were barely enough men to garrison the city; there were none to protect the countryside.

One lone knight of Champagne named Hugues de Payens decided that there was something gravely wrong here. What good did it do to take back the Holy Land, if it was still too dangerous a place for pilgrims to visit? With the help of his brother in arms Godfrey de St. Omer of Picardy, they gathered together seven more knights, probably in the year 1119, and vowed to patrol the road from the coast to Jerusalem, in order to protect the Christian pilgrims. What made this vow remarkable — absolutely unprecedented in Christian history, in fact — was that they promised to live as monks as well. Theirs was the holiest of missions, and they decided that the drinking, whoring, and brawling of the typical knight was not appropriate for them. Instead, they voluntarily chose to live by the monastic rule, swearing poverty, chastity, and obedience, on top of the vow to put their lives on the line each day to see Christian pilgrims safely to Jerusalem.

The Templar order grew, though we have no figures from such an early period. They applied for official recognition from King Baldwin of Jerusalem, which he granted eagerly, offering them the plum quarters of the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount, just opposite his own palace. The Christians did not call this place Al-Aqsa, but rather the Temple of Solomon. From here came the various legends of the Temple of Solomon that would forever be associated with their name.