Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

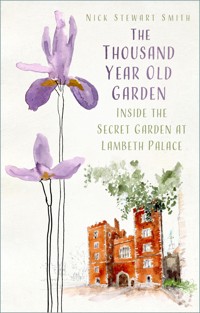

'A fascinating and intimate portrait of a garden over time … Reading is like being given a rusty key to a beautiful secret garden.' - Ben Dark, Author of The Grove Hidden away behind high stone walls in the centre of London is Lambeth Palace Garden, a 10-acre site that has been continuously cultivated for more than a thousand years. Join Head Gardener Nick Stewart Smith as he unlocks the gates and invites us to wander through a secret garden where nature is at the heart of everything and where a thoughtful approach to gardening creates a haven for all sorts of native wildlife, allowing nature to flourish in the midst of one of the world's busiest cities. The Thousand Year Old Garden is a comforting meditation through the seasons on the act of renewal, hope, gardening, and our place in nature.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 264

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Gillian

With special thanks to Kirsty McLachlan at Morgan Green Creatives for her help and guidance with this book

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Nick Stewart Smith, 2023

Illustrations © Ellie Gibson

The right of The Author to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 305 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

Late Spring

The Blakes of Lambeth

By the Fig and the Olive

A Wild Orchid

Early Days

The Tulip Tree

In the Labyrinth

Summer Glades

Long Grass

Flight

Growing Produce

Scythe

September Walk

Potato Eaters

The Chapel Garden

November in Colour

Rainy Days

Hand Tools

The Spirit of the Beehive

Going to Trafalgar Square

Mycelium Underground

Spring Comes Again

INTRODUCTION

Nearly all of my working life has been spent gardening. For ten years, I was a National Trust head gardener in Devon, moving to the Chequers Estate in the Chilterns for a further seven years, followed by another six looking after the Archbishop of Canterbury’s historic garden at Lambeth Palace. At all these places, my time was spent outside among the plants. I hardly ever wrote anything down, nothing more than a page or two of notes, and it never occurred to me to try anything longer, let alone attempt to write a book.

Then, a little while ago, I gave a guided tour around the garden at Lambeth Palace for a couple named Claire and Seán. I must have given more than 500 guided garden tours over the years, but this one was somehow different and the warm autumn afternoon we spent together has stayed with me. There was an unusual energy in the air and the conversation seemed to flow easily from one unexpected observation to another without prompting.

The tour ended by a strawberry vine I had carefully trained on the rails by the herb garden, a new plant now heavy with small grapes that were sweet to taste. Any gardener is always inexplicably proud when something they have planted reaches the point of bearing fruit or flowering fully for the first time. So, I encouraged Claire and Seán to try the grapes before saying goodbye to them.

‘You should write all this down,’ said Claire, referring back to the tour.

‘Ah, yes, well, I don’t know …’ I mumbled in reply.

‘No, you should. You should try,’ she said.

A few days later, on arriving at Lambeth Palace, I found that Claire had left her most recent book for me, Miles to go Before I Sleep: Letters on Hope, Death and Learning to Live (Claire Gilbert, 2021). I read it over the next week and it made a deep impression on me, helping me in ways I could not have foreseen.

In my pigeon hole with the other post there was also a brand new notebook. I took this with me and began to write sentences on the pages, one word after another slowly growing into something much longer until all the pages were filled and I had the beginnings of this book.

Everything is strangely quiet this morning. It is seven o’clock and I am crossing the Walworth Road, usually a mass of cars and lorries with grunting engines coughing toxins into the spring air by this time of day. But now there is almost nothing here, just a red bus, empty of passengers, that pulls with a sigh to a stop where nobody is waiting.

I am making my way to Lambeth Palace, where I work as a gardener, around 3 miles from my home but an easy stroll through small parks and side streets. As I get nearer to the Thames, the traffic turns heavier with drivers anxious to progress but stuck at the lights in long queues. Exhaust fumes linger in the air but the trees lining the street have fresh, green leaves and they are giving off a sweet scent.

At the junction where the wide span of Lambeth Bridge appears, I see glimpses of the immense brown river flowing underneath. People are on the pavements even at this early hour, some of them might be tourists as they are carrying cameras and seem a little dazed, taking pictures of themselves standing in front of the palace’s medieval brick towers, which look vast and powerful this morning.

I am a few minutes late, so I walk quickly towards those towers where there are two wooden doors, one big to allow vehicles to enter, the other much smaller for someone on foot, like me. Lambeth Palace is beyond the doors, workplace and home to the archbishops of Canterbury for more than 800 years. Surrounding the buildings are 10 acres of secluded gardens, which are even older than the palace, hidden away from view behind high brick walls through the centuries, hidden away from the noise and bustle of a changing London.

I knock on the door and hold my breath for a few seconds. The traffic rumbles by and then I hear the shuffle of footsteps on the other side as a security guard approaches. The door swings open and I walk in and cross the courtyard, then through a small stone arch where another world opens up before me, a secret garden filled with its own kind of sound and movement, its own light and colour.

Five olive trees were delivered towards the end of March. I had to go away for a short while and those trees made it through the gates just too late for me to do anything with them. So, they were left strapped close together, held captive on a narrow, wooden palette that I dragged behind the greenhouse. Earlier this morning, I could at last untie the trees, get them out and transfer them into bigger pots where they would have more light and a little more space to grow into. Those olive trees could breathe again.

The middle of London is a very long way from the dry, stony fields where they started as saplings in southern Spain, baking in the heat of the long Andalusian summers. Given the opportunity, and with a bit of luck, they might spend the rest of their lives in their new northern home; lives that could last several hundred years at least. I have nearly thirty of them now, beginning to form an avenue either side of the wide gravel path running behind Lambeth Palace.

With my wheelbarrow, I am walking down that path between the lines of olive trees. A small group of NHS staff are gathered around one of the old benches there, all dressed in their uniforms. St Thomas’ Hospital next door has been given a spare key to the garden’s back gate so that the staff can come and go from over the road as and when they wish, even if that is only for half an hour to get some rest, to find some peace for a brief time in the quiet green surroundings.

The air might be cold today but the sky is a brilliant blue above with some shade provided by the new leaves unfurling on the trees, and there is birdsong all around. It feels like a good place to be. They can sit there on the old oak bench with the rest of the world at a distance, there is no need even to speak. Hopefully, the working day moves a little further away, at least for a while, giving some time and space to prepare again for whatever is to come.

With the sun rising higher, I leave my barrow to move further down the gravel path and onto the grass. Like most mornings recently, this one will be spent watering the many terracotta pots and oak barrels placed around the garden, as well as giving a little water to all the things that were planted in the early spring. Everything is so dry now that I can feel the parched ground as hard as rocks under my feet when I move across the lawn.

Despite the difficult weather, I can see a lot of the incidental plants are doing well; they include foxgloves, wild gladiolus and nigellas in various shades of blue. All seem to have flowered a little earlier than might have been expected. These self-seeders are like nomads wandering through, stopping at different areas of the garden each year, where they show off their flowers, display their colours and maybe reveal their scents before they pack up for the season, turning up somewhere else next time. They can catch anyone unawares, which does not seem such a bad thing, appearing as they do unexpectedly where there is just a little dapple of shade, a little water, somewhere to pause and flourish, if only for a brief time, before moving on, always moving on.

Their seeds ripened last autumn as the rest of the plant died. Some seeds are no more than fine dust floating on the air, unsure where they will land. But when they do – and the situation suits – little root tendrils are sent down to explore the dark soil, hurrying to begin new life before everything else can crowd the space and close the light. This year, there has been a good germination and the garden is full of those early flowers: snapdragons, larkspur, purple toadflax and all the others. It’s like a dream.

As these self-seeding, nomadic, wild things drift through the space, they provide a kind of bridge for the garden between the late spring and the true beginning of summer. There is usually a natural pause in flowering just then, those few weeks when the early blooms are over and before the perennials get going in all their glory come June.

It is never easy to find a balance gardening this way, to decide which chance seedlings are wanted and which, perhaps, are not. I intervene now and then, and the decisions I make will change from year to year. But there is not too much intervention; I shouldn’t forget to just allow things to happen around me and give those wandering plants some room to roam. I let them choose for themselves where they are going to go – which might not be where I had been thinking they ought to go. It becomes a back and forth, a conversation. The garden is allowed to speak and it’s not just you or I trying to impose our will on it. Instead, another voice is present. I think gardens are always speaking to anyone who cares to pay attention.

Of those self-seeding plants I have been looking at, foxglove and larkspur are described as North European natives. Some of the others, the gladiolus, the snapdragon and the purple toadflax, have their origins in Mediterranean areas, while nigella comes from further away, from eastern Europe and Asia, although now it is widely naturalised across much of the world.

The fascination with non-native plants has been a part of gardening in most places for hundreds of years, a fascination with the strange and the exotic. But there should still be space for the indigenous plants. For example, if the lawn I am standing on were allowed to grow a bit longer, especially now, in late spring, some of the suppressed native plants could come through. Plants such as cat’s ear, yarrow or knapweed would have a chance to flower, along with the daisies, buttercups and speedwell, providing much to attract many kinds of insects. Relaxing the mowing in this way across thousands of gardens could make quite a difference when put together, creating huge swathes of rich habitat, with lawns no longer a monotonous, even green but instead scattered with tiny flowers like jewels, the grass studded with colour and scent.

I have walked across the hard surface of the grass and up the short flight of stone steps to a raised terrace that cuts across the middle of the garden. Spring bulbs are flowering everywhere, including the more recent additions of orange tulips and deep blue muscari. When the rains come in the autumn and the days turn colder, I might be found hidden away in the shed being tempted by the descriptions in catalogues for various bulbs and seeds, wondering what new things to get, calculating how much I can afford. I keep my eye on the native selections as I try to find a balance with those plants from faraway lands that have been so attractive to me for so long.

Next year, I could increase the numbers of snowdrops, wood anemones and snake’s head fritillaries, wild daffodils too. Maybe not all natives, by definition, but at least with a centuries-long history in the north European landscape.

As I add new things, I am trying to observe and survey in more detail what is already present in the garden, creatures as well as plants, and to write it down each day in a notebook. And if that could be done through the years, I could build a picture of the changes that are taking place with the wildlife in the green space around me.

It is still spring but it feels as if summer is already somewhere nearby and there is a lot going on. The roses are just beginning, they are going to have a good year with hundreds of flowers already in bud. The air sings in anticipation and I detect a faint perfume, although no blooms have opened yet. Alliums are also making their presence felt with delicate globes in different shades of purple floating above the borders, while blood-red astrantias can be seen here and there, along with many chance columbine seedlings.

The iris are also looking good at the moment, from soft white to pale blue to rich purple, with some newer ones of copper orange. These plants are named for the goddess Iris, who carries messages from the earth to the heavens by ascending on the arc of a rainbow, her bridge, and in that way allowing the living to send messages to the dead in the worlds beyond. In modern Greece, purple iris are still planted on the graves of women to summon the goddess, so that she can guide their souls from this world to the next.

The hours go quickly by and, too soon, the day is nearly over, although neither the watering nor the weeding are quite finished. The hospital staff left their resting place around the oak bench ages ago but I didn’t see them leave. I expect a group of them will return again tomorrow. For me, only an hour or so remains and there is so much to be done – but not enough time, never enough time.

The spring breeze picks up from the west and I hear the faint sound of last year’s leftover dead leaves stirring in the hidden corners of the garden. I will leave them in peace. I know that down in the decaying brown of those leaves there are safe places for all kinds of creatures to make a life. I will leave some of the twigs and branches that have fallen from the trees, make neat stacks of them so that they can rot away in their own time, crumbling to provide a whole world of possibilities for bugs and other wildlife.

Pausing for a short while in the shelter of the herb garden, I am looking at the torn electric cable that used to carry the power to the pump in the small round pond. There is no mistaking those teethmarks, something has bitten right through the wires – foxes, on their nightly patrols around here, no doubt. They sense movement in these types of cables, tiny vibrations, and they attack in the hope of finding something alive and interesting inside. All they could have got for their efforts with that particular cable would have been a sudden slight shock as they crouched there in the shadows to chew through the black casing, exposing the electric current while, in the night garden around them, the dark waves of aromatic herbs would sway softly in the moonlight.

With the cable broken, the pump has been disabled and this has allowed a layer of green blanket weed to cover the pond surface. The fox sabotage gives me a reminder that the electric pump should have been replaced long ago with a pump powered by a small solar panel. I will get to that soon. But in the meantime, there is a lot of green weed to be cleared.

Looking closer, I find the dense living blanket is inhabited by dozens of little smooth newts, and it takes quite a while to free each of them. Some lie still in my hand for a few moments, as if playing dead, then struggle furiously as soon as they sense the chance to escape and disappear at speed down into the safe depths of the pond where it is dark. One I was untangling from the blanket weed even covered its face with its front limbs, finger digits all splayed, eyes shut tight, maybe hoping in that way not to be seen. After all, if I can’t see you, then surely you can’t see me. Or can you?

Those juvenile newts will crawl out of the water as the summer reaches an end and their gills are gone. They will find somewhere to shelter in the undergrowth of the surrounding planting before returning to the pond to breed as the weather warms up again the following year. I leave them to it, walking away with the gravel path crunching quietly beneath my feet. The sky has become overcast, layer on layer of low cloud, grey on grey. I think it might rain after all.

A punctured bike tyre and no repair kit means I have to go to work on foot again today. I leave the apartment block in the early morning and start walking along Blake’s Road, where I live. It is usually a quiet street. At this hour, just before sunrise, nobody is around. The spring is still here and there is even a little ice on the pavement as a reminder that winter has not quite gone. The various cars lined up by the kerb all have frosted windshields. We are in the north part of the borough, traditionally known as one of the rougher parts of Peckham, although it doesn’t seem so bad today, especially with the first rays of morning sun piercing the luminous grey sky.

The street where I live is named for William Blake, due to his childhood associations with the area. His habit from around the age of 7 was to take long solitary walks far from his family home in Soho, and on some occasions, he even walked the 6 miles in a southerly direction to get to one of his favourite places, the big green common at Peckham Rye. That open space is still there, much appreciated by the locals and not far from where I am now.

More than 250 years after young William Blake passed this way, when the apartment block where I live was built, the builders chose to name it Blake’s Apartments in a kind of tribute to the poet, I suppose. It is a nice enough building, a conventional low-rise residential block of the twenty-first-century style, finished in the same way as many of the other buildings in the area. Of course, there is no knowing what William Blake might have made of all this – a modern block of flats named after him – but if he had anything to say, it would be something surprising, I imagine.

Walking from Soho to Peckham Rye would have taken him a couple of hours at least. It is a long way for such a young boy to go for a stroll all alone, stepping out into a world where any number of things could have happened. One day, on reaching the Rye, he looked up into one of the trees and saw that it was filled with angels. He saw their bejewelled wings outspread among the branches, spangled and sparkling as if covered with stars made of fire.

Some twenty-five years after that spectacular childhood vision, by then still largely unknown in his calling as an artist and poet, he moved with his wife Catherine into a small house in north Lambeth at No. 13 Hercules Road. They lived there from 1790 to 1800, their top floor overlooking the grounds and gardens of Lambeth Palace, which in those days extended much further than now, nearly double the present size, so that the garden walls would have been on the other side of the Blakes’ new street.

In that house in Hercules Road, the two of them imagined and produced much of the work that is still admired all around the world more than 200 years later, including the finished versions of Songs of Innocence and Experience, which they self-published in 1794. Imagery is woven through those songs that involves gardens, trees and especially flowers – their species, shapes and colours are always of key significance. The engraving on page 43 of the 1794 edition of Songs of Experience has three of the works most strongly inspired by the language of flowers, ‘My Pretty Rose Tree’, ‘Ah! Sun-flower’ and ‘The Lily’. For me, as a gardener at Lambeth Palace, it is curious to reflect that the extraordinary flower imagery of these works was produced while the Blakes were living alongside the 20 acres of the palace gardens.

Catherine and William Blake had a garden of their own adjoining their Lambeth home and it is recorded that they planted a fig tree and grape vine, among several other things. The now world-famous Lambeth Palace fig tree in the garden opposite would already have been nearly 250 years old by then. It must have been of a considerable size and well known in the local area. It is possible that the Blakes’ fig tree was a cutting from their neighbour’s vast garden. Back then, I don’t know if one of them could have simply knocked at Lambeth Palace’s forbidding entranceway and asked for a cutting or two. Perhaps those gates were always kept shut tight with ‘Thou shalt not’ carved into stone over the archway.

It seems unlikely that they would have obtained a fig cutting in those days just by asking at the front door. I wonder if they could have befriended one or two of the gardeners at the palace. They lived so close by, right next to each other, for ten years after all, so it is possible the Blakes were given a small fig tree in secret by one of their gardener friends; something special, quietly handed over the high wall as the rosy dawn was filling the sky above Hercules Road. Catherine Blake’s father was a gardener by profession and she might have known very well how to deal with cuttings and plants of most kinds, including fig trees. With the skills and knowledge gained from growing up in a home where gardening was the main source of income, I think it is possible that she could have guided the planting of the Blakes’ Lambeth garden.

With William often occupied in the rich and strange worlds of his extraordinary imagination, it fell to Catherine to take charge and manage the couple’s often fragile finances. She was also closely involved practically with the many artworks they created; her significant contributions were not fully acknowledged at the time, nor over the subsequent years. She mixed the colours used in the paintings and illustrations, carrying out some of the colouring herself, while also becoming a skilled engraver and printmaker, essential for the production of the beautiful books they assembled at home. Her role in the work was active and essential, it was a two-person venture.

Their marriage was very close and lasted for forty-five years, until William’s death in 1827. Catherine lived for another three years, managing on small loans and help from friends as well as by selling some of the paintings she and William had made. Neither of them had much recognition for their work in their lifetimes, one telling example being the only review of William’s self-funded 1809 exhibition in Golden Square, which stated, ‘The poor man fancies himself a great master and has painted a few wretched pictures.’ The show itself was very sparsely attended and that review may have been the only one in print the Blakes received while William was alive.

Among the precious objects the Blakes produced while living in Lambeth for those ten years is a hand-finished relief etching titled God Judging Adam, dated 1795. The composition shows two powerful figures, physically mirroring each other, as it should be, for we are told that Adam was created in God’s own image. The Bible also tells that Adam was the First Man and was shaped from clay and soil.

The two figures in the etching may look the same but their stances are very different. Adam is strong and muscled but his head hangs low in despair, his long grey hair drooping around his face, while the figure of God is opposite, seated above Adam among bright flames in a chariot made of fire and pulled by horses with manes made from flame. There is a book open on God’s knees, although no writing is visible.

The Blakes’ composition is dominated by the dynamic diagonal line of God’s arm and long index finger, sending what appears to be a white beam of light through the top of Adam’s bowed head by way of punishment or maybe illumination, possibly both. The expression on the face of the figure depicting God is difficult to read. I have looked at the face for a long time and would not describe it as an expression of wrath or anger, although definitely something is there. The feeling is more a mixture of sorrow and disappointment, almost resignation, as if knowing that this was always the way things would turn out.

Made from the clay of the ground, Adam, the First Man, has also sometimes been referred to as the first gardener: ‘Now the Lord God planted a garden in the east, in Eden, and there he put the man he had formed … and put him in the Garden of Eden to tend and to keep it’ (Genesis 2:8). In the picture I have in my mind, I see Adam on his knees working in that garden, a small figure surrounded by the wonders of the immense green world so full of life all around him.

The painting God Judging Adam is to be found these days as part of the Metropolitan Museum’s collection in New York. More than 200 years after it was completed in Hercules Road, the picture is now a prized treasure in a renowned museum on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, some 3,500 miles away from Lambeth. Considering it was once among artworks that were described as ‘wretched’ in their own time, a place in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection does not seem too bad.

William and Catherine Blake endured the hardships and seemed to shrug off the unkind jibes that came their way as best they could. They carried on, somehow never losing their faith in what they were doing, the two of them together, maybe not having very much but getting by with hope as their currency. It is reported that the combined version of Songs of Innocence and Experience had sold fewer than thirty copies by the time of William’s death – fewer than thirty copies sold in over thirty years. Now it is believed there are twenty-eight copies of the original printing still in existence, all individual with unique variations. Although most are carefully preserved in libraries and museums around the world, one or two still remain in private collections. Imagine glancing at the bookshelf at home and seeing a hand-finished original copy of Songs of Innocence and Experience just waiting to be taken down and opened.

As I venture out into the garden today, the storm clouds are gathering above and the sky looks a metallic grey but ready to dissolve at any moment. Standing here with eyes uplifted, I’m still thinking about the Lambeth Palace gardener at the top of a ladder handing a fig tree cutting over the high wall to the Blakes, who are waiting on the other side as arranged. It would have been early in the morning, with the air quite cold, a thin layer of crystal frost covering the ground as the little tree in its terracotta pot is safely exchanged; a precious thing handed over the wall from one gardener to another.

More than 200 years later, I am still wondering about all of that while walking back along Blake’s Road in Peckham on a spring evening, slowly home to Blake’s Apartments. There are no angels in the trees, there are no stars of fire up there among the branches, at least none that I can see. Maybe next time – you never know.

To see Eternity in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an Hour

From ‘Auguries of Innocence’ by William Blake, 1803.

Yesterday, a message was received in the garden office. It came from Sergeant Major Saheed Khan, who is stationed at Sandhurst, and described a recent visit to Lambeth Palace. He wrote that he was especially impressed by the ancient fig tree in the main courtyard and wondered if he could have a couple of cuttings to grow, with the idea of eventually planting a new tree outside the mosque in Redditch, his hometown. There, it would act as a living symbol, he wrote, to show the ‘unity, tolerance and good relations between Muslim and Christian’.

For many centuries, gardening has played a significant role in Muslim tradition and culture, with the gardens of Islam being some of the finest ever created anywhere. They contained plots for growing useful plants – those that would provide medicine, food and other practical materials. But their gardens were also held to be something more. They were places for relaxation and pleasure, valued as secluded and peaceful places with quiet areas for thought and contemplation. Usually, a small pond would be found at the centre with channels of water running to it from the corners of the enclosed area. The water was to provide gentle sound and movement, while the high walls surrounding the garden were to provide shelter and protection. Neat paths would be laid out just inside the wall perimeter, encouraging the full use of the space as a whole.