Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dreamspinner Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

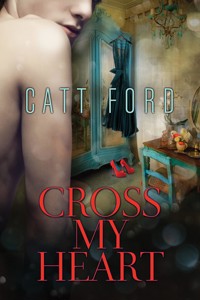

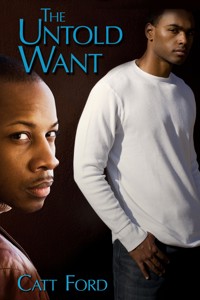

A professional life hitting all the highs is poor compensation for a personal life hitting all the lows. Myles Winston is divorced, isolated in a cocoon of loneliness when he's not at work, and adrift in a sea of despondency with no idea how to break out of the rut. Then a chance encounter with Davion, an old school friend, brings back such visceral memories of their "experimentation" that Myles finds himself pursuing a secret affair with him. But Myles is still struggling with his fear that he may be a disappointment to his parents, and he must be true to himself before he can step into the light of day and reach out for what he truly wants—Davion in his arms forever.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 152

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedication

The untold want, by life and land ne’er granted,

The Untold Want

EVEN at that hour in the morning, the scent of roasted chestnuts from the street vendors filled the air, along with the bells being rung by the volunteers tending the Salvation Army buckets.

At least in the financial district he didn’t have to listen to the sickly sentimental sound of the “Little Drummer Boy” emanating from department stores, although all the other usual signs of Christmas were everywhere, even though it was still before Halloween.

It was ironic to Myles that, in the wake of the financial crash, he was one of the few who not only still had a job but also plenty of money. The problem was he had nothing and no one he wanted to spend it on. Still, he went to work faithfully every day. Why not? He didn’t have much else to do.

Pausing with his hand on the doorknob to admire his own name spelled out in brushed steel letters, Myles walked into the front office where Tanisha sat behind the curved desk, her face lit up by her monitor. She was the only thing he had taken with him when the old firm had fallen away from under his feet.

He stopped short when he spotted something new hanging on the paneled wall in a prominent position. Pointing at it, Myles demanded, “What is that—mall art thing?”

Tanisha craned her head and smiled eagerly. “It’s a painting.”

“Is that a Thomas Kinkade?”

“Why yes, I do believe it is. Do you like it?”

Myles took in the innocent, hopeful expression on Tanisha’s pretty face and swallowed his impolite response. Even though Tanisha was not as guileless as she looked. “It looks like a print.”

“It is,” Tanisha said. “I can’t afford real art.”

“Oh yes, you can, and anyway, I said I’d get something for the walls,” Myles said.

“Yes, I seem to remember you saying that about ten months ago when we moved in,” Tanisha said with an air of one fondly reviewing a distant event. “And yet it still looks empty in here, like you just crash-landed here by accident.”

“Except for the sign,” Myles said.

Tanisha rolled her eyes. “Oh yeah, the sign. Good thing your name is on it so nobody blames me for this cell.”

“You know my taste doesn’t run to—that sort of thing,” Myles said, pointing at the quaint cottage with flowers lining the path and a homey glow in the windows. “Besides, with people losing their homes—”

“Pretty tactless, huh?”

“You did this to coerce me into picking out something else, didn’t you?” Myles asked, light dawning. At their previous employer, Tanisha had decorated her office with African masks.

“Yes, but I adore how careful you’re being not to insult my taste.” Tanisha smirked. “Don’t worry, it’s not mine, I borrowed it from my mother. But it’s going to stay there until you come up with something better.”

“I’ll go to a gallery this afternoon,” Myles promised.

“I’ve heard that before. Look, Myles, I know things have been rough….” Tanisha paused.

Myles shook his head slightly, warning her off sensitive territory. The fact that his marriage had gone down the tubes with the market left him feeling surprisingly relieved, with just a tinge of sadness and regret, although he still didn’t want to discuss it. The writing had been on the wall; it was hardly a black swan event.

“But if you don’t want your clients thinking you picked that horror out, you will find something better. Or I’ll break out the masks,” Tanisha threatened.

“Not the masks,” Myles teased.

“Yes, at great personal sacrifice, I will strip the walls of my condo bare, bring them here, and drive nails into that awful retro wood paneling you’re so in love with. Then I will hang my masks all over and people will think we’re a front for a tour service to West Africa.”

“I have one appointment this morning, and then I’ll be free after lunch. I’ll take a walk to Chelsea and see what I can find,” Myles said, checking his watch.

“Myles,” Tanisha instructed, “don’t get anything bland and corporate. I have to live here too, you know.”

“I know.”

“Not that I have anything against corporations, depending,” she called after him.

“Better not. They have money too,” Myles muttered.

As soon as he sat down, his private line rang. Glancing at the caller ID, Myles drew in a deep breath before he picked up the receiver. “Hi, Mom,” he said.

“Good morning, Myles.” Her formal greeting seemed to be an indirect rebuke for the casual way he’d answered. “It’s good to finally get you on the phone in person. Your answering machine never calls me back.”

“I’ve been busy, Mom.” Myles stared out at the glimpse of gray sky between the surrounding buildings.

“Apparently your voice mail has been too. You work too hard.”

“You always said that idle hands are the devil’s playground.” It amused Myles slightly to use her own homily against her, even though he knew he couldn’t win this one.

“Work is fine, but not to the point where you don’t take the time to see your own parents,” his mother said, firmly putting him in his place. “We haven’t seen you in months. We would like to see you for dinner Sunday.”

“I can’t, Mom—” Myles started mechanically.

“Not this Sunday, next weekend. Surely you haven’t scheduled anything that far in advance. Besides, we’re not that far away. We live in Queens, not another state.”

The unspoken threat was clear, and Myles knew he would have to capitulate. Usually his mother managed to guilt him into coming at least once a month, and he’d staved her off for three. “Will Grandma be there?” His grandmother Mimi was still feisty and full of sass in her eighties, and she made him laugh.

“Well, of course. She does live with us, you know.”

Myles smiled, both at the hint of distaste in his mother’s voice and the one pleasure he got from visiting his parents. “What can I bring? A bottle of wine?”

“Nothing, Myles. Just seeing you will be enough.” His mother paused and then hurriedly said, “Well, I’ve got to run, and I’m sure you’re busy as usual. See you in two weeks then, Myles. Be sure to be on time and wear a tie. We’ll eat at seven.”

She hung up before he could utter a word of protest. He hated her hit-and-run tactics, and the way she screwed him into visiting when it was the last thing in the world he wanted to do. He was sure she would be asking probing questions about his social life and then suggest he meet some friend’s single daughter. This was a set-up. His mother just couldn’t seem to leave it alone.

When Tanisha rang to tell him that his client had arrived, Myles turned his attention to finances in relief. At least there was something he was good at.

AFTER a quick lunch at his desk, Myles cut over to Broadway, planning to walk to Chelsea instead of catching a cab. Belatedly remembering Tanisha’s instructions, he regretted not Googling black art before he left. There was no lack of galleries, but he hadn’t thought about how difficult it might be to identify one that carried something that would appeal to both Tanisha and him. Unless it happened to be called The Black Arts. Myles almost laughed at the imaginary name, but he didn’t have the energy.

After suffering through the generic corporate art that hung on the walls of his old firm, Myles wanted to look at something he would enjoy every day. He might have enjoyed the idea of Tanisha’s masks, boldly staring down his clients waiting in the outer office, but he didn’t want her to empty her own walls. She had proved her faith in his strategies by investing a percentage of her salary with him at their old firm. Ironically, when the housing market crashed, she had finally been able to realize her dream of actually owning her own place. She had bored him for months, sharing paint chips and decorating strategies, and he didn’t want her to wreck that now because he simply couldn’t be bothered to decorate the office.

Another irony that gave him a bitter chuckle was the switch in their circumstances. Now Tanisha owned her own condo with a water view, while he was living in a tiny studio rental with a single window looking out onto an airshaft. His wife—ex-wife—had kept the expensive duplex co-op with the view of Central Park, and he was the one sleeping on a foldout couch in a one-room apartment. He seemed to be frozen in one spot, not caring enough to even look for a better place. Stationary. Stagnant. Bored.

None of the paintings that hung in the windows of the galleries he passed inspired any ardent response within him. He kept walking, wondering just how long that Kinkade was going to be on his wall, when his attention was caught by the name of a gallery across the street.

The Black Swan.

Myles crossed the street to peer in the window. Taking a deep breath to steel himself, he walked inside. He wasn’t used to going to galleries. It looked like nobody was home, and the gallery seemed to be in disarray, with canvases leaning against the walls as if someone had just taken them down. Or perhaps they were putting them up. Spotlights lit empty spaces on the grey walls, but Myles wasn’t fussy. He was fine viewing the paintings where they sat.

The portraits in the first room were painted with bright, cheerful colors, and Myles tried to imagine the effect against his walls. The painter seemed enthralled by women; all his subjects were African-American females wearing dresses and turbans of stylized tribal fabric. Myles thought that perhaps Tanisha might like something less… thematic. Or maybe she’d love these. He should have asked more questions.

And besides, the small painting that had first caught his eye in the window seemed to be by a different artist. Even to his untutored eye, the difference in color and technique made it easy to tell.

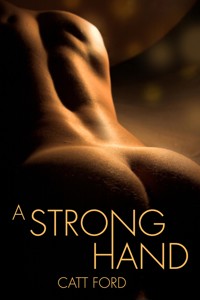

His breath caught when he entered the second room, and he stopped short, stunned by the haunting beauty of the paintings, all in warm tones of ivory, amber, caramel, and chocolate. This had to be the same artist whose work was in the window, but Myles hadn’t expected to be entirely surrounded by life-size nude men. In a panic, he glanced around quickly but found he was alone with his pounding heart. His first cowardly impulse was to leave immediately and learn to live with the Kinkade, but before he could bolt, he had to look at one particular painting on the wall up close.

It was rendered in a realistic style, capturing the scene almost as precisely as a photograph. It was framed tightly so that he couldn’t see the entire face, only the curve of the man’s jaw, his neck, the way his shoulder bunched with tension, part of a naked back. The man was standing next to a chain link fence through which a basketball court was visible, with the players blurred in motion as if by a camera’s depth of field. Light and shadow delineated the curve and dip of muscle under the man’s chocolate skin. Sweat beaded on his back, and a pinpoint of sunlight dazzled off one droplet sliding down his bicep.

A rush of sense memory hit Myles like a hurricane, so intense it was like he’d been suddenly transported back in time. He could hear the slap of the ball against the asphalt and his palms, feel the heat of the sun on his skin, his nostrils were filled with the scent of masculine perspiration. He shut his eyes, unaware that he was swaying in place, following where memory led him; the cool darkness of deep shade under the bleachers, the bite of strong fingers digging into his flesh, the feel of hard, firm muscle straining against him, the tang of bitter, salty come in his mouth.

“It’s wonderful, isn’t it?”

The voice snapped Myles back to reality, and he realized he was panting. He needed a moment to compose himself before he turned to see who had spoken to him. A droplet of sweat slid down from his armpit and dampened his shirt.

“Yes—yes, it is.”

A well-groomed black man with graying hair stood there smiling at him. The man had to be in his fifties, and from his proprietary attitude, Myles inferred that he was either the owner or the manager of the gallery.

“You might enjoy some of the other pieces by this artist, although the floor isn’t the ideal way to view them.” The manager waved his arm invitingly at the other paintings leaning against the walls. “We’re in the process of hanging for the opening.”

“I—I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have just walked in,” Myles started.

“Of course you should. That’s why we leave the doors unlocked.” The manager smiled gently. “He’s very talented. I expect that I shall be giving him a solo show very soon. It’s very evocative, isn’t it?”

“Takes me back to the old days on the playground,” Myles managed to say with a dry mouth. He swallowed hard.

“Let me get you some water,” the manager said.

“I don’t want to put you to the trouble.”

“It’s no trouble.” The manager held out his hand. “Jermaine Kolahi.”

“Myles Winston.”

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Winston. I’ll be right back.”

Myles unbuttoned his overcoat and fished out his handkerchief to mop his forehead dry. Glancing swiftly around, he caught no sound or sight of the manager, so he leaned in closer to check the painter’s signature. D. Robinson, he made out, squinting to focus his eyes. He wished he’d brought his readers with him just to be sure. Could it be….

Kolahi came back and handed him a bottle of cold water, companionably opening one for himself. For the first time, Myles noticed that the man was dressed simply but expensively in a good polo shirt and designer jeans. He felt stuffy and overdressed in his regulation dark suit, white shirt, and navy tie, but maybe it was just that Kolahi was wearing casual clothing for hanging the show, as he’d said. Somehow, Kolahi came across as rather formal in manner, making the jeans seem like weekend wear.

“Thank you.” Myles twisted off the cap and drank thirstily. The cold water hit him like an ice bath, helping to put out the slow burn that had ignited his groin when he saw the painting. He realized that he was half hard and hoped it didn’t show. By rights, he should be celebrating; he hadn’t had a good hard-on in at least a year. “This—this artist, D. Robinson—” He stopped, knowing that the silence would get the other man to speak.

“Davion Robinson,” Kolahi said.

His heart was thundering in his chest so loudly that Myles was sure the other man could hear it, although Kolahi gave no sign of noticing anything unusual. “I—knew a Davion Robinson once, in school. I wonder if it could be the same man.”

“You might wish to come to the opening, then. He’ll be here.” Kolahi barely touched Myles’s elbow to guide him to another piece. He bent and picked up the painting, hanging it on the wall for better viewing. “He calls this one Zebra. Of course, you know that zebra often refers to the offspring of a black and white couple. This is a little private joke on that slang.”

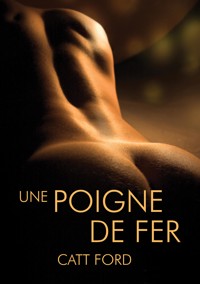

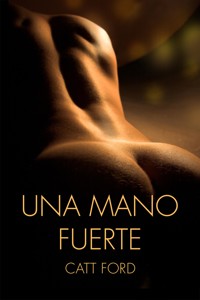

Unseen venetian blinds cast stripes of light and dark over the rich cocoa skin of a naked male. His face was obscured by shadow, leaving the voluptuous mounds of his buttocks as the focal point as he lay sprawled on a bed. The lines of light followed the curve of his cheeks, reaching shadowy fingers into the valley between them.

Myles felt the fire inside him flare up again. It was almost painfully sensual, as if the man were waiting for his lover to come and take him from behind. He shook his head, trying to chase the thought from his brain. Whatever had made him think of that? It could just as easily be a man taking a nap or enjoying the warmth of the sun. But Myles knew that his visceral reaction was correct; the sensuous splay of limbs was too inviting, and the smooth skin reminded him of gleaming satin.

“I like dark chocolate better.”

He whipped his head around to stare at Kolahi, but the man hadn’t spoken; he was still gazing at the painting. The words must have been an echo from the past, audible only to him. He wondered about the first painting he’d been drawn to, realizing that the color of the man on the outside of the fence looking in matched his skin perfectly.

And the skin of the man sprawled so unselfconsciously, unaware of the voyeur greedily eyeing him, was the exact color of Davion’s—at least as far as he could remember.

“I want to buy that painting. The first one I looked at,” Myles said abruptly.

Kolahi’s thin, perfectly shaped eyebrows rose in practiced gratification, and Myles was surprised to notice that he must pluck them.

“We haven’t even opened the show yet.”

“I must have it. I can’t take a chance of losing it. How much? Whatever you want.”

“I suppose I could mark it as sold, if you would agree to leave it here for the opening. I already have the walls planned out. Besides, you haven’t even seen the rest of Davion’s work; you might like another better.”

“I’ll leave it here for the duration of the show, if that’s the way it works, but I must have it,” Myles insisted. He couldn’t bear the thought of someone else owning it, looking at it, looking at him. Because he knew exactly what Davion must have been feeling when he painted it. It was a part of their past, a symbol of the secret they had shared between them.

“Very well. It’s marked at five thousand dollars, sir.” Kolahi’s gaze traveled over Myles’s clothing, as if assessing whether he could afford such an expensive impulse purchase.

“Check or credit card?” Myles asked.