3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: FINN Books Edition FireFly

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

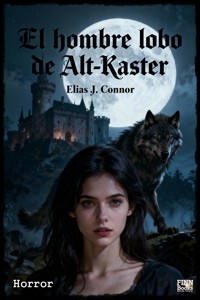

When Anna Zielke returns to her home village of Alt-Kaster after her grandmother's death, she has no idea that the old legends she used to laugh at as a child are a bloody reality. Between the narrow alleyways, the mists of the Kaster Forest, and the unspoken secrets of the villagers, Anna soon senses an eerie presence that grows stronger with each full moon. The clues lead deep into the family history—to an ancient pact that should never have been made. The more Anna learns the truth, the more she herself is drawn into the vortex of a beast that not only threatens the village but is also awakening within her. Caught between human and monster, guilt and responsibility, Anna must decide whether to embrace or destroy the legacy—and what price she is willing to pay. A dark, atmospheric novel about legends and guilt, about community and exclusion—and the question of whether the true monster lives in the forest or within ourselves.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Ähnliche

Elias J. Connor

The werewolf of Alt-Kaster

Dedication

For my girlfriend.

My companion, muse, fairy.

Thank you for being here.

Chapter 1 - The full moon promise

Evening falls coldly over Alt-Kaster like a heavy cloak. The last light pushes between the tiled roofs, drawing the chimneys long and gray, and the church tower clock strikes slowly, each movement a small thunderclap in the cool air. On the cobblestones, the first frost lies at the edges of the cracks; the leaves that rustled during the day have turned to crackling paper and spin forlornly in the gutters.

Thin smoke drifts from the chimneys, smelling of burning wood and dry grass. The lingering scent of fresh bread hangs in the air outside the bakery, even though the door has long since closed; behind the windows, the empty counters lie like memories. A lantern casts round islands of light onto the street, its glow dripping down the walls and lengthening the shadows until they creep across the alleys like black fingers.

People move quickly, collars pulled up, hands buried deep in their pockets. A few steps, a hurried laugh, then silence – conversations are now shorter, as if the cold were an argument against lingering. A bicycle briefly parked on a corner, a closed shop, the click of a shop door: small, clear sounds in the thick, cold silence.

On the edge of the village, the Kasterer Forest presses against the last garden hedge like a dark promise.

The wind rustles through the trees, carrying the damp scent of moss, wet leaves, and earth; it lifts the branches, letting them scrape against each other, and somewhere a dog answers with a long, lonely howl. The old windmill at the edge of the field groans occasionally, a weary breath echoing between its beams and emphasizing the vastness of the night.

If you listen closely, there's something else: the distant clinking of a bottle in a backyard, the murmur of voices growing faster, as if they don't want to give the darkness time to settle. People's breath hangs white in the air, small clouds, short and fragile, immediately crushed by the cold. And above it all, the sky stretches like a dark blanket, already embroidered with the first cold points of the stars – clear, hard, and unwavering.

The reception at the small hotel is as austere as Anna expected—and yet it hits her like a cold hand. The reception desk is a dark wooden desk with a yellowed sign above it bearing the name "Hotel Klose." Behind the desk stands a middle-aged woman with her hair pulled back and a face that wears a smile as if it were an unfamiliar sight. Mrs. Klose hands Anna the key as if it were a transaction and says dryly, "Room three, upstairs on the right. Breakfast is served from eight." Her voice contains no sympathy. Anna smiles, forces her name, and states the reason for her return: "My grandmother has died." She sees the woman briefly, almost imperceptibly, narrow her eyes, as if trying to push away a memory.

Outside the hotel, the autumn wind is blowing; Anna pulls up the collar of her coat and feels as if the cold is creeping not only from outside, but from within the village itself. She is twenty-five, her brown hair tied back in a practical bun, her features sharp, her shoulders not narrow, but tense. Professionally, she has been far enough away to allow herself a detached perspective—project manager in Düsseldorf, deadlines, no room for sentimental returns—and yet there is something in her stomach that cannot be soothed by logic: a heaviness connected with the name "Agnes."

In the hotel hallway, she hears the other guests clattering their plates, a man's laugh in the corner; she longs to join in, to absorb the familiar warmth of a pub, but everywhere she looks, she senses reserve. The few people she sees avert their eyes, as if such a conversation could be better avoided. It's not open hostility—that would be easier—but a muted distance that says: Here, someone has delivered a chapter that they'd rather not reopen.

The next morning, she sets off for her grandmother's house. The walk is short; Alt-Kaster is small enough that the pulse of the place is measured in minutes. The houses stand side by side like tolerated guests. Anna still knows every corner, although her steps are unsteady at first—then more confident. Familiar smells greet her: ground coffee, wet leaves, the tart note of chestnuts. Children flit past, a school bus drives by, short and tinny, and someone calls out a name mischievously, a name that isn't hers.

The house where Agnes lived stands at the end of a narrow street; a two- story timber-framed building with faded paint, the garden overgrown, the wood of the veranda darkened by the rain.

The windows are still closed, the curtains gray as dust. The front door swings open surprisingly easily under Anna's hand; a set of keys lies under a small stone next to the stairs—just as her grandmother always did. Anna thinks of her grandmother's hands: small, hardened fingers, always groping for the cups, always working in them. She enters.

A crucifix hangs in the hallway, beneath it a small coat rack with hooks holding coats long since abandoned. The air smells of lavender and old books. A stack of letters lies on the table, untidy, as if the house had only been vacated yesterday. The living room retains the scent of polish and vanilla; the furniture sits in familiar places, the armchair where Agnes knitted for years is worn into its shape. Anna sets down her suitcase, inhales the scent, and feels a wave of memories wash over her—Christmas with smoked salmon, summers when Agnes made iced tea, the cats that slept on the stove.

She decides spontaneously: I'm moving in here. The hotel room, with its thin walls and impersonal breakfast buffet, now feels like an escape—an escape she no longer wants. Her grandmother's house is a promise of permanence, even if it's crumbling. Anna puts a mattress in the guest room, unpacks the bedding, and creates a small corner with a side table and a lamp. Later, as darkness falls, she sits in the armchair with a cup of tea in her hands, and the house breathes around her; it creaks, it releases little sounds that no hotel ever makes.

The first few days pass in a fog of stacks of paper and boxes. Anna sorts accounts, opens drawers, pours the remaining lavender from a tin into a preserving jar, and labels it "Agnes – Garden." Bills on one side, letters on the other. It's the mundane things that make up the estate: pharmacy receipts, packets of seeds, a collection of handwritten recipes, scribbled in messy handwriting. Sometimes her hand catches on a line – a name, a year.

She feels like a puzzle coming together while simultaneously revealing new edges.

But the villagers' coldness persists. Anna tries to sell the household items: plates Agnes hand-painted; a silver teapot that gleams on its side at dinner; an old rocking horse with a name carved into it. She rings the neighbors' doorbells, takes samples to the small antique shop on the street, posts notices on the bulletin board in Mrs. Mertens' shop. Everywhere the reaction is the same: polite refusal, a "We have enough ourselves," or an averted gaze. Once, Mr. Jansen, the former owner of the general store, gives her half a glance and says in a carefully measured voice, "Some things are memories. We don't like to take things that are... well. It's better to leave them as they are." Anna doesn't press the issue, because in this village, words are often louder when they remain unspoken.

She tries a flea market in the next biggest town; she brings boxes full of porcelain, a typewriter, a brass knife. But transport is expensive, and the response is less than expected. Buyers hesitate when she has to explain where the items come from. "Old Kaster? No thanks, no time," some murmur, and Anna feels the desire to sell quickly morph into a shame she doesn't want to share. She had hoped that practical items—plates, irons, bed linens—would simply find new homes. Instead, she encounters walls: not out of envy, but rather an instinctive protective reflex. People treat the objects as if they were still alive, as if they had threads to the past that shouldn't be so easily severed.

One morning in the bakery, where the scent of yeast and sugar offers a temporary warmth, she overhears a conversation. Two women placing their purchases on the conveyor belt speak in hushed voices. They pause as Anna approaches. One of them is the pastor's wife, slender, wearing an apron still stained with flour. Their glances become brief, friendly, but they remain silent. Anna greets her, introduces herself: "I'm Anna Zielke." The pastor's wife nods, her lips whispering, "From Agnes." It sounds almost like an incantation. Then she lowers her gaze and pushes the bags on. A small gesture, an uninvited kindness, yet Anna feels the distance like a knife.

A man who had caught her eye on the very first day runs into her at the market. He's the forester, Mr. Berg, a broad-shouldered fellow in a rough jacket, his hands bearing the marks of lifting heavy logs. His gaze lingers on Anna, scrutinizing, not hostile, but suspicious. "So you're staying?" he asks, and there's no judgment in the question, only interest. Anna replies, "Yes. I'm sorting through the estate." He nods slowly, says nothing more, and then adds, almost casually, "The nights have changed." Anna has the feeling that he knows more than he's letting on—and that Old Kaster knows things that go unnoticed in other villages. But she doesn't make a drama out of it yet; for her, they're just words that will later take root like seeds.

She tries to fill the loneliness of the house with work. She clears out the attic; cobwebs hang from the ceiling like fragile curtains. Under a protective sheet, she finds boxes of photo albums: yellowed pictures of young women in long skirts, of men posing proudly, of dogs with tightly bound leashes. One photo captivates her: Agnes as a young woman, with thick, dark hair, her face soft, her eyes large. Next to her sits a man Anna doesn't recognize—an ancestor, perhaps, or a mysterious acquaintance. Along the bottom edge of the photo, in a scribbled hand, are the words: "Summer 1958." Anna holds the picture, feeling the cold of the house mingle with a warmth emanating from the paper itself. She sets the photos aside, labels the boxes "Memories," and stacks them neatly.

After a few days, when the first nights in the house keep her awake longer and the sounds become more unfamiliar, Anna hangs a sign on the front door: "For Sale – Household Goods, Antiques, at Fair Prices." The idea is pragmatic; perhaps visibility will bring buyers, perhaps the distance will disappear if the items are openly offered. But the response is lukewarm. A young man from the savings bank only takes a quick look, a couple from the city drives by and surveys the rooms with glances that seem more suited to renovation than collection. No one stays to negotiate. Sometimes curious eyes linger at the garden fence, people who judge without taking action.

In the evenings, Anna often sits alone at the kitchen table, surrounded by papers she doesn't sort right away, a candle flickering, the stove ticking. She looks out at the street; a few people walk by, but no one rings the doorbell. An elderly neighbor, Mrs. Weiss, once brings her a bowl of stew and places it a meter and a half away from the door. "I'm just dropping it off and going," she says, smiling wearily. Anna opens the door, takes the bowl, and invites Mrs. Weiss in; the woman shakes her head. "No, no. It's all right. I thought you might need it." It's a gesture that shows affection, but it's tinged with caution. Mrs. Weiss isn't cold, but she wears the caution like a second skin. "Things aren't the same as they used to be," she murmurs as she leaves, "some stories are better left in the cupboards."

The rejection gnaws at Anna. She's self-assured, she can handle rejection, but this kind of reticence hurts in a different way because it isn't due to any personal failing on her part. It's as if everyone is sitting at the table, and someone has silently excluded her. One evening, after locking the door and letting the silence of the house settle over her like a blanket, she hears a dog howl from the edge of the woods. It's a long, clear howl that fades into the darkness. Anna sets down her cup and listens. The sound is like a question, a cry into the void.

On the third day of sorting, she comes across a box of documents that seem different from the bills—thicker paper, densely written, with a faded seal. In an envelope, she finds handwritten letters, apparently addressed to Agnes; the handwriting is old-fashioned, the language warm and heavy. One of the letters contains a line Anna wasn't expecting: "We did what was necessary to survive. But the village must never know the same." Anna frowns. Who "we" are isn't clear; the letter isn't dated. A small slip of paper, used as a bookmark, bears the words, in her grandmother's handwriting: "Just for you, Anna, when you come back." Anna closes the envelope and feels a tug in her chest, an excitement more akin to curiosity than fear.

She hesitates for a long time about whether to read the letter. Privacy is sacred, her father always explains when he talks about family matters. But the note lies there as if it had been waiting for her. Slowly, almost solemnly, Anna opens the envelope. The handwriting is simple, clear: “My dear Anna, by the time you read this, I will be gone. Forgive me my secrets. I wanted to protect you, not burden you.” Then follows a series of names and dates, records of debts, of people in the community who sought her help. It sounds like a web of favors and minor risks that Agnes juggled—that someone in need was helped, that someone else had to pay for it. But the last line strikes a darker note: a note, a word that is not explained—“The Pact.”

Anna places the letter beside her. "The Pact." It sounds like a sentence from an old novel, like a tale told to children as a warning. But in Agnes's handwriting, it carries weight. Anna takes a deep breath and decides she won't run away. She will stay, sort through the papers, search for answers. Perhaps it's just a metaphor for a long bargain—a private promise—but the way the village reacts makes her believe there's more to it. People may keep secrets more than they'd admit.

The nights are growing longer. Once, as she sits late in the kitchen sorting old bills, the power goes out; darkness descends like a curtain. Candles flicker, and the sounds of the house come to the fore—a water pipe working softly, a window trembling in its frame. In the distance, beyond the gardens, she hears the howling again, this time closer, more insistent. Anna gets up, goes to the door, looks out at the path, at the trees moving in the wind. No one is to be seen. Only the silhouette of the windmill stands out against the sky.

She shakes her head, laughs softly at herself, moves the candle closer, and continues reading. She knows that Old Kaster has things no city knows: stories lurking in the cracks, memories that won't go away because no one bothers to clear them away. And she also knows she won't turn back. The coldness of the people remains a challenge, but not an obstacle she'll surrender to. Agnes left her house behind, and with it, a box full of questions. Anna puts the letter back in the box, gently closes the lid, and whispers, not quite sure to whom the words are addressed: "I'm staying. I'm sorting things out. I'm finding out what you've hidden."

Outside the house, the shadow of the forest lengthens; a gust of wind carries leaves past, swirling like tiny ghosts in the candlelight. Anna pulls the blanket around her knees and listens to the ticking of the clock—the quiet, steady heartbeat of the house. Outside, the howling stops, as if respecting a boundary, a small, invisible ring it must not penetrate. Anna closes her eyes. Tomorrow she will continue sorting things out, tomorrow she will talk to the forester, to the pastor, to anyone who can help her understand. She is tired, worn out, irritated—but she is not alone in her pain. The silence in the house is not just emptiness; it is an invitation to do something.

As the house breathes in the night, Anna thinks of Agnes's hands, the stories told around the kitchen table, the smile Agnes once gave her when Anna was small and afraid of the dark. "The dark has its reasons," Agnes had said. "Sometimes it's just animals. Sometimes it's people." Anna wonders which category her grandmother's secrets belong to. She knows only one thing: if something in Old Kaster was looking for her, it will find her now—and she won't run away.

Chapter 2 - Blood on the clay path

The morning is gray, a narrow strip of light tries to break through the cloud cover, but the village remains hushed, as if it has agreed to an uncomfortable confession. Anna pulls her coat tighter, her hands in her pockets, her breath forming small clouds as she walks along the narrow dirt road. She has the photos and letters in a bag; the heavy envelope containing Agnes's notes lies like ballast at her heart. She plans to speak with Mr. Berg, the forester, today—because he is the one who knows the fringes of Old Kaster, the paths no one else takes. But even at the corner where the path forks, her steps remain uncertain.

"Have you seen this?" a voice calls from behind her. Two teenagers are standing by the fence, hands in their pockets, hair tousled by the wind. As Anna approaches, they look at her, uncertain, curious.

“What?” Anna tries to remain calm. She doesn’t want to sow panic, doesn’t want to provide a platform for rumors – and yet her stomach feels like a knife: the memory of Agnes’s last line, “The Pact.”

"On the clay path. The tracks. Blood too. The police were here." One of the boys nods towards the dirt track leading into the Kasterer Forest. "At first we thought it was a deer, but... well."

Anna nods, without showing how fast her heart is beating. "Thank you," she says and continues walking, her steps now purposeful. The clay path isn't far from the house; in a few minutes she'll be standing where the village road narrows into a path.

Even from a distance, something chaotic is visible: white markings, a narrow strip, as if someone had hurriedly crossed the grass. Police tape flutters softly in the wind – yellow, matter-of-fact, almost out of place in the rural setting.

"Good morning." A man in a dark jacket, with a thin scarf and a hat, stands next to the tape. His name tag identifies him: Mr. Kahl, a police officer from Bedburg, who is in charge. His gaze lingers briefly on Anna, as if assessing her, then he hands her a folded page with a series of photos: footprints in the clay, tears in a coat, and a bonus of dark spots on the ground.

“You are Anna Zielke?” he asks. His voice is practiced, but somehow indifferent – the face of someone who often sees cups and papers, not tragedies.

Anna nods. "Yes. That's near my grandmother's house."

He looks at her, and for the first time since her arrival, she feels a direct, unwavering attention. "You live in the house? Good. We're still looking around. It was a local resident who found the tracks. At first, we thought it was an animal, but... well." He pauses, the words failing him, as if they were too big for the narrow street.

Anna leans over the photos. The prints are strange—not quite like deer tracks, not like dog tracks. The outlines are longer than a human foot, but wider, with an indistinct bulge at the heel that almost looks as if the print had been drawn. In one spot, there are scratches in the clay, curved lines that don't correspond to a normal gait.

"What do you say?" Anna asks.

Mr. Kahl pushes his cap back. “We don’t know. Not for sure. It’s difficult. It could be an animal that’s somewhat deformed—or people who left something behind. The blood…” He lowers his voice. “The blood doesn’t quite match an animal bite. But that’s preliminary. We’re taking samples.”

“And the coat?” Anna asks. The photos show a piece of fabric, half-torn, pulled on a hedge. A dark stain, as big as a hand, is emblazoned across it.

"Half burned. Or torn apart. We found him there." Mr. Kahl looks out over the fields. "No body. No missing person report so far. Some say someone was called out at night. I don't know."

Anna kneels in the cold clay, even though her fingernails immediately turn red. The prints lie there like a silent text. She places her fingertips close to one of the edges of the print, without touching it. The earth is damp and freezes quickly, as if the cold were preserving the event. A small strand of hair clings to the edge of one print—light, almost white, in contrast to the dark ground. Anna carefully lifts it and places it in an envelope. Science, she begins to think, and a strange sense of responsibility grows within her: she is not only an heir, she is a witness.

“People are whispering,” a voice suddenly says behind them. Anna turns around. A woman is leaning over the fence; her face is etched with deep wrinkles, her hair thin, her eyes wide and clear. The dogs have left her, but her voice carries something that commands attention—not the desired normality, but the weight of something that has long since gone unheard.

“Mrs. Mertens?” says Anna. She knows the name: the old woman who sometimes sits in the bakery, whom people smile and ignore because she carries too much of the past.

Mrs. Mertens nods slowly. "They call me crazy, so be it. But I have eyes. And ears. And the old people spoke when I was a child. 'Gealt,' they'd say. 'Gealt.' That's not a word you hear often. They said it when the nights became different." She leans forward, her voice becoming a whisper that cuts through everything, despite the ribbons tied to the trees. "Don't you see? It's starting again."

A few of the farmers standing at the edge exchange uneasy glances. One clears his throat as if to say something reassuring. "Oh, Mertens, don't say such things. We have foxes and stray dogs here, nothing intellectual." He tries to hide his laughter in his voice, but his eyes remain fixed on the tracks.

“Gealt,” Mrs. Mertens repeats, looking directly at Anna. “You are Zielke. Agnes’s granddaughter. Your grandmother often helped me. I’ll be watching over you while you listen.” In her eyes flashes something more than superstition: a sad certainty, one that has been around for years.

Anna feels her stomach clench. The words "violence" and "the pact" collide like two keys suddenly striking the same chord. She swallows. "What exactly does that mean?" she asks, her voice as matter-of-fact as possible.

Ms. Mertens exhales. “It’s an old word. Not in the books, not in school. Long ago, in this country, there were things that couldn’t be explained. Some said they were curses. Some said they were animals with souls. We called it Gealt when a person became night and never returned to day.” She looks at the group, which is now suddenly silent. “I’m just saying what I know.”

Mr. Berg, the forester, slowly comes around the corner, tall, with broad shoulders, his boots caked with mud. He holds his hat in his hand, his face looking tired. "We shouldn't get carried away with stories," he says, but his voice trembles slightly. "We're taking samples. We're examining the tracks. As long as we don't have proof, they're just tracks."

"Samples of what?" Anna asks. "Human or animal?"

“Both,” Kahl replies tersely. “The DNA will tell. We’re transmitting it to the city.” He scratches his chin, suddenly looking very young, as if the uniform and the band weren’t supporting him. “But tell me one thing, Ms. Zielke: Did you hear anything unusual? Noises? Footsteps?”

Anna thinks about the nights of the past week – the howling that reminded her of a question echoing in her bones, the shadows that stretched out as if they had a consciousness. She says: “I heard a howl. Last night. It was close, but not like a dog. More like… a cry.”

Mr. Berg growls softly. “The howling is older than we are. I hear it occasionally when the wind is blowing in the wrong direction. But it’s not often. When Mr. Kahl takes samples here, we also check for animal movements. It could be anything.” He tries to normalize the conversation, but his hands are now trembling noticeably.

The villagers grouped themselves, opinions were divided; some spoke loudly, others whispered, but beneath the noise lay a thin, seeping core of fear. Anna stood there, Agnes's letters warm in her bag, her mind working: if it truly was something ancient, then it was bigger than superstition. If the marks were neither human nor clearly animal—then the space in between was where old stories took root.

“Will you leave it behind?” Mrs. Mertens asks, as if she already knows the question and just wants confirmation. “Or do you want to see what’s left behind?”

Anna feels the pressure of their stares. "I'm going to look into it," she says slowly. "I want to know what happened."

In the afternoon, the commissioner's young assistant arrives from Bedburg, wearing rubber boots and displaying a meticulousness reminiscent of an exam. He takes samples, packs hair, scrapes the floor, photographs the remnants of the coat, and notes everything down in long, practiced sentences. He asks bite-sized questions that Anna has to answer: when she last left the house, whom she saw arriving, whether her grandmother had any enemies. His questions are matter-of-fact, but between the lines, there's a sense of something more.

"Did Agnes have someone who might be stalking her?" he asks.

Anna thinks of the old villagers, the disagreements, the letters with their hints. "Not that we know of. She was popular, but she had... secrets. She helped, she hid, she worried." Anna hesitates, but her courage grows with curiosity. "She mentioned something in a letter. One word: 'The Pact.'"

The young man raises an eyebrow. "The pact?"

"I don't know what it is. Not yet." Anna senses that she is standing at a threshold. "But I have a feeling that it's connected to this."

The sun is sinking, the village is enveloped in a grey chill. The police are packing up, promising to deliver the results this evening – DNA analysis will take time, they say. The people slowly disperse, returning to their homes, where radiators whistle and children's voices briefly fill the air.

Only Mrs. Mertens remains when the fence is almost empty. She runs her hand over the bark of the old wooden fence, as if she were reading the stories through it.

“Take care of yourself, Anna Zielke,” she says finally, and there’s no mockery in her voice, only a wrinkle of hope. “It’s testing you. Not just the night. People too. Sometimes both are harder.”

Anna feels a mixture of defiance and relief. "I know," she says. "I'm not the child who runs away anymore."

When she returns home in the evening, the light in her grandmother's living room is dim. She makes herself a cup of tea, sits by the window, and looks out. The clay path lies still, like a vein coming to rest. But within her, there is no stillness. The words "Gealt" and "The Pact" circle like two unfed birds—they know something is coming, and they don't know if it will be benevolent.

She opens the box of documents again. Among bills and photos, she finds an old collection of newspaper clippings from decades ago, reporting on sheep killed by predators and dogs gone missing. The articles bear names she recognizes—families still living in the village. One yellowed page reads: “Nights of terror in Alt-Kaster: Shepherd reports inexplicable attacks.” The report is brief, factual, as if a writer were describing something he doesn't dare to interpret. Anna puts the newspaper aside, her hands trembling slightly.

Outside, the silhouette of the windmill stands out against the sky; further away, somewhere in the Kasterer Forest, a single howl breaks the silence—brief, like a wink. Anna puts down her cup, stands up, places her hand flat against the window, feels the cold through the glass. She thinks of Agnes's hands, the cross in the hallway, the box labeled "Just for you." She knows now that she is not merely the heir to material possessions; she is the heir to a history that weighs heavily and is perhaps dangerous. The question before her is not an academic one: Does she want to know the truth, no matter how ugly it is? Or will she leave things as most do—behind closed doors, buried in silence?

Anna exhales.

"I want to know," she whispers, more to herself than to the room. "No matter the cost."

Night settles like a blanket over Alt-Kaster. In the distance, a howl sounds again, this time longer, more intense. It doesn't just sound like an animal; it sounds like a cry seeking answers. Anna gazes out the window for a while longer, until the sound fades away. Then she turns off the light and goes into the bedroom. Under her pillow lies the letter with the handwritten note: "Just for you, Anna." She closes her eyes, but sleep remains elusive. Outside, the wind rustles in the woods, and somewhere in the dark branches, something creaks, as if stirring.

Chapter 3 - The chronicle of the Night

The night creaks softly in the nave like old wood that has grown accustomed to the cold. Anna closes the door behind her, even though she knows the lock no longer holds properly; the wind has set its rhythm. She came here without much thought—an irrational impulse, a need for a place that has grown longer than the hotel, than sales signs, and than mistrust. The church smells of wax and cold stone; from the altar, specks of dust rise like tiny planets into the beam of a streetlamp that filters through one of the tall windows.

In the front of the nave, two candles burn in simple brass holders. Someone placed them recently; the wax is still soft. Anna runs her hand along the edge of a pew and sits down, her coat wrapped around her. The silence here has a different density; it feels like fabric that embraces everything protectively yet conceals nothing. She thinks of Agnes, of the heavy scent of tea in her kitchen, of the small, firm hands that used to hand her knitting needles. Why does it feel as if Agnes's spirit is sitting right behind her, asking if she's doing it right now?

She gets up and walks quietly to the side entrance—to the parish library, located in the annex next to the rectory. The door is only ajar; Anna thinks the priest has probably forgotten to close it. Or perhaps he isn't expecting her. A faint flicker in the room suggests a lamp; someone is here, she is not alone. Before knocking, she pauses, letting the silence test her senses a second time.

“Anna?”

The voice is surprised, but not shocked. Pastor Martin emerges from the semi-darkness between the bookshelves, an old flashlight in one hand, his face bearing the marks of a night watch. He isn't wearing his Sunday stole, his shirtsleeves are rolled up, and his glasses are askew. His gaze lingers on them, not reproachfully, but rather questioningly.

“I couldn’t sleep,” Anna says, saying it in a way that doesn’t sound like an apology. “I wanted to light a candle… for my grandmother. I thought this would be the best place.”

Pastor Martin nodded, his voice soft. “You are welcome anytime. Agnes was… she was a constant presence in this congregation. I knew you would come. Child’s play of providence, isn’t it?” He smiled briefly, then pushed his glasses up: “Why are you in the library? The archives are usually closed.”

Anna glances at the door. “The door was open. And I… I need something other than paperwork in my room. Peace and quiet, maybe some answers.” She says the last word more quietly, as if she hadn't quite wanted to confide it to herself.

The pastor studies her for another moment, then pats his hands dry as if about to begin work. "If you're looking for answers, you've come to the right place – but not in an easy way. The archives are full of old records and chronicles, some of them significantly older than today's parish regulations. Some documents you'd rather not find, and yet here they are."

“I’ll take what I can get,” Anna replies and follows him into the small, winding room.

Dark wood shelves fill the room; in the corners stand leather-bound volumes, their spines showing cracks in the gold leaf. A ladder leans against a shelf, and the smell of parchment and old glue wafts towards her. She sits down at the massive table in the center, where a stack of volumes lies next to a kerosene lamp.

“Why so late?” asks Pastor Martin, as he takes a blanket from a chest and carefully pulls it back. His hands are steady, his movements familiar. “The chronicles are… delicate.”

“Because the truth seems to be less loud at night,” says Anna. “Because I don’t want anyone to hear me asking.”

He smiles, but it's not a cheerful smile. "I can understand that. Good. Then pay attention to what you find. Some stories... they live on, not necessarily because they're true, but because we keep calling them up."

Anna looks at an old volume with the handwritten title: "Chronicle of Alt-Kaster — 1703–1900." The writing is dense, in ink strokes that must still have come from a quill pen. Next to it lies a thick, pressed bundle labeled "Community Records — 1898–1950." Pastor Martin hands her the chronicle first. "The families of the villages," he says, "often keep their family trees here. You'll find births, deaths, marriages—and sometimes squabbles, because people are trying to explain things."

Anna opens the chronicle; the pages rustle, releasing a breath of bygone air. Names flash before her, inviting brief, sharp memories: Zielke, Klenke, Mertens, Berg – names that still resonate in the village. She flips through the pages and her gaze lingers on an entry from 1837; the pen has laid down a heavy dot.

"August 21, 1837 – Report from shepherd Heinrich L.: several sheep killed, bizarre bite patterns, no signs of predators, only deep scratch marks. Village meeting sees mysterious causes. Proposal: Nightly vigils and prayer. Signed: A. Zielke."

Anna reads aloud, even though no one asked her to.

The name Zielke is written there in neat handwriting, like a signature confirming the law of things. Her heart beats faster, but her fingers remain still. "My great-great-grandfather?" she murmurs.

Pastor Martin glances over her shoulder. "The Zielkes are an old family here. Some of their members were church councilors, others sextons, still others… well, they had influence." His voice trails off. "Sometimes too much."

Anna continues turning the pages. Numerous entries describe nocturnal phenomena: "Howling in the night," "Missing dogs," "Tracks like two simultaneous steps stretching out." One protocol, dated 1901, bears the simple note: "Agreement not to discuss the incidents publicly. Atonement will be kept private." Next to it, in a different, more hastily written hand, is a note: "The pact is renewed."

“The Pact,” Anna reads, and the words echo. She thinks of Agnes’s letter, the note “The Pact,” and the word Mrs. Mertens whispered: violence. An icy knot tightens in her stomach. “What does that mean?”

Pastor Martin pulls his chair closer, his brow furrowed. “This isn’t a legal document that protects you,” he says. “These are words people have chosen to call agreements that take place outside our legal system. I’ve heard stories since I first came here—stories you’d expect to find in books of legends rather than in council minutes. But they’re here. They’re written down. That doesn’t make them true, but it does make them real.”

Anna touches the line "The pact is renewed" with her finger. The ink is pale, as if someone had tried to conceal something.

"With what?" she asks quietly. "What kind of pact?"

Pastor Martin sighs. “It’s rarely specified in concrete terms. Mostly it’s euphemisms: ‘sacrifice’ becomes ‘atonement,’ ‘expenditure’ becomes ‘levy.’ It’s called protection against hunger, compensation for a bountiful harvest—things that conceal rational reasons. And then there are the words passed down orally, which no one writes down for fear that they might have power.”