3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

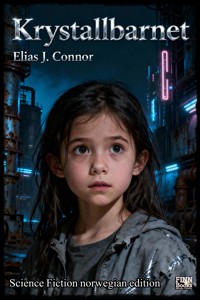

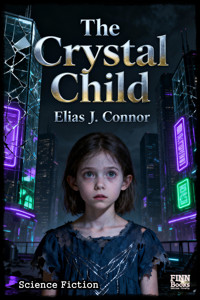

- Herausgeber: FINN Books Edition FireFly

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

They call her sensitive, fragile, quiet. But that's just the surface. When Raymond and Melanie adopt a shy, seemingly strange girl named Lisa, no one suspects how much their lives are about to change. Lisa rarely speaks about herself—yet her eyes seem to see worlds hidden from others. Her new brother, Prince, senses it first: something about her is different. Gentler. Deeper. And sometimes unsettling. Lisa reacts to emotions as if they were tidal waves. She senses fear before it's even spoken. She comforts without knowing how. And one day, she touches a dying man—and brings him back. What initially appears to be sensitivity soon becomes a truth greater than the family is willing to accept: Lisa is no ordinary child. She is a Crystal Child—a being whose consciousness transcends the limits of humanity. And she is not of this world. While Prince tries to protect her, others learn about her: a reporter searching for answers, a shadowy organization collecting what it doesn't understand, and beings who have lived among humans for millennia—the Annunaki. A race begins between science and faith, memory and forgetting, possession and freedom. A novel about perception, solidarity, and the quiet power that sometimes awakens in a single child.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Elias J. Connor

The Crystal Child

Dedication

For my girlfriend.

You are unique, one of a kind, and special.

I'm glad we found each other and are walking our path together.

Prolog

The sky above the desert gleams with an unusual coldness, a startling blue that defies the usual yellows of the day. It is still before the true heat; the sun hangs low, casting harsh shadows across the sand, yet at the same time something alien weaves a silver band across the firmament—tiny at first, then larger, like a school of fish approaching in formation. Three large bodies come into view, heavy, geometric, and behind them follows an armada of about a hundred smaller companions. All are pyramid-shaped, angular, as if someone had recreated the shape of the desert itself—only much, much more precisely, from metal that shimmers in the air.

The people on the banks of the great river, standing knee-deep in the water drying fish or cutting reeds, first see only an intensified glow on the horizon. A child cries, a dog howls, and for a moment the world holds its breath. Then a soft, deep sound descends to earth—not noise, but rather a pulsating rise that makes the sand vibrate beneath their feet. It is not thunder, not a storm; it is the breath of something that does not belong to the earth.

The three large structures arrive first, silently like shadows, and land with a serenity that seems to defy all laws of supposedly known gravity. The sand forms soft curves on their flanks, small dunes that nestle against smooth, metallic sides.

The form is perfect: a pyramid, except that no stone is visible within it. No building layers, no walls, no human framework. Only flowing edges, colder than any stone. The smaller ships scatter and find space on nearby levels, as if they shared a common plan, a secret order they shared among themselves.

The Egyptians, the present-day inhabitants of that stretch of desert later called the Nile, knew nothing of such forms. They knew hills, rocks, and the occasional image of a god created by an artist, but they had never seen anything so perfectly geometric. The shamans and priests of the early settlements were the first to interpret its meaning: if the heavens themselves sent a form, it could not be an ordinary natural phenomenon. They gathered, they knelt, they folded their hands—the ritual was immediate, instinctive: who could know what power would come over humankind when the geometry of the heavens aligned with the geometry of the earth?

As the loading ramps of the large, pyramid-like ships gently lowered, the astonished onlookers beheld beings who appeared surprisingly human. They were slimmer than most of the people who lived here, their skin had a warm, pearly sheen, and their eyes were large, dark as polished ebony. Their bodies were wrapped in garments that resembled neither cloth nor leather, but a kind of translucent weave that shimmered in the light. At their temples were small attachments, smooth rings whose function no one knew. They moved with the composure of those accustomed to a hundred thousand years of technology and not paralyzed by the turmoil of an alien planet.

Some of the elders bow automatically. They know how the stories go: strangers come, strangers bring gifts or ruin. But the strangers don't speak. Instead, one of them extends a hand, and a projection of a star map appears on the sand: lines, dots, symbols of worlds none of the people will ever see. An image of movement, from place to place, of arcs of light. It is a language that penetrates directly into the eyes and the heart, without the need for words—the people feel awe, but also a ticking unease, as if their own world were suddenly too small.

The first to touch the strangers are not the chiefs, but the children. Children have not yet learned to fear the unfamiliar; they accept the other as if he were one of the many possible faces of creation. A boy giggles, extends his hand, and one of the strange figures bends down; the contact lasts only a heartbeat. The boy laughs loudly, and this laughter is like a diploma, a permission for peace. The adults hold their breath; some weep.

The strangers—soon called "gods" in the tongues of the people—take their place like uninvited guests, yet bear their presence with a serenity that makes it possible to accept them. They display no weapons; all they bring is knowledge, devices, and tools that work instantly yet gently: water filters that draw clear drinking water from murky water; seeds that sprout even in salty sand; metal rods that capture light and transform it into warmth without the need for fire. The people are overwhelmed; the gods give and take nothing by force. They teach, they give tools, and the settlements grow as if they had been waiting for centuries for precisely this knowledge.

But not all reactions are purely religious. Some of the younger ones—those who are still curious and have an aptitude for technology—look more closely. They follow the strangers under the wings of the night, observe their work, study the lines of the pyramid-shaped structures that appear like otherworldly temples. They see how mechanisms open with exquisite precision, like an inner core, like a heart, from which light and current flow. These young men and women are not thinking of gods; they are thinking of workshops, of workings, of the idea of understanding things. A few of them dare to ask—in simple gestures, in hands reaching for tools, in questions flashed through their eyes, as direct as the questions of children by the river.

The aliens respond in their language not with words, but with demonstrative patience. They show how to shape a shovel from bent metal, how to dig channels through the sand to direct the river's water, how to fit stones together to bear loads. Soon, structures emerge that humans have never known before. It is as if the extraterrestrials are holding a mirror up to early civilization and saying, "Here is what you can become." They teach mathematics in pictures, drawing axes, angles, and cycles in the sand. They give humans symbols, showing how crowds organize themselves, how teams work. The humans begin to regard these aliens with awe, with gratitude—sometimes with arrogance.

But all gifts come at a price, and every great change brings questions that defy easy answers. The priests, seeing their place at the top of the old hierarchy lost, murmur behind the scenes. They watch with watchful eyes, for such technological teachings change not only bricks and water, they change power. A new council is forming, comprised of those who have adapted: merchants, builders, those who profit from the new knowledge.

Another council is formed from skeptics who distrust the influence of the foreigners, from old people who say that one should not trust the gods.

The aliens, however, operate with the patience of the stars. They do not stay every day; they come in cycles, working on day-long projects that seem like rituals, and then they withdraw to the inner chambers of their ships. They demonstrate concepts and then leave the tools behind. They are not brutal; their superiority is quiet, their power structured. Some people begin to see them as intermediaries—intermediaries between this world and an order that seems greater than their own.

And then comes the moment when the aliens do something that will change the world: they partially bury their ships in the sand. Not completely, but enough so that only the tips protrude, gleaming like the summits of mountains made of metal. It is not an act of cowardice or fear; it is an order they are carrying out, a purpose they have. They leave the great pyramidal structures to rest, their bases deep in the sand; the edges disappear, the flanks bury themselves, and the people do not immediately ask why. Perhaps they think the gods want to remain, a monument demonstrating their power. Perhaps they understand that it is a protection, a kind of preservation of their technology in another medium: earth, which settles over the years like a shell.

The great ships, half-buried, still gleam with a metallic sheen for a while. People come and see: there stands something otherworldly, a new sanctuary. They build small temples around the mounds, they bring offerings, and over time, things become intertwined: the top of the ship becomes part of a cultic structure, but the base, hidden in the sand, remains a technological resource not immediately accessible. The strangers avoid teaching how to retrieve the ships. Perhaps it is part of a lesson, perhaps a test.

Learn with what you have, not with what you take.

Centuries pass. The metal, originally smooth and new, weathers. The sand rubs, the wind carries, the sun leaches. A patina forms on the surface—not just rust, but a change that roughens what was once smooth. Layers of sand accumulate, dung heaps and dust cover the smooth surfaces. People come, work, rely on the forms without knowing their precise origin. The prows of the former ships still stand out, but their sharpness softens, the mountains become blunt, the edges lose their original precision. The longer time passes, the more the memory of what was once highly technological and alien fades. Stories of gods intertwine with legends of builders, shaped by human hands—stories that will later reinforce the stonemasons' customs.

The architecture of the early settlements takes on the form that later generations would call pyramids. But the first builders, in those early centuries, still knew of their foreign origins; they had images, they had songs. A few priests wrote things down, sketched stars, compiled lists, and ensured that stories were passed down that still revealed the outlines of the true form.

But in the next generation, and in many after, "gods who came from heaven" become a memory so distant that it becomes mythical. The metallic spire, which once reached towards the sky like a finger, almost completely disappears in the blazing desert sun; the people who once knew it die, and they are replaced by people who know only the pyramid, not the ship.

Over the centuries, a new culture emerges in which the pyramid itself becomes a symbol: power, order, the connection between earth and heaven. The form, originally high-tech, is adopted as an architectural canon; people learn to build with stone themselves, inspired by something they no longer fully understand. The pyramid as an idea is now stronger than its origin: it has become a symbol with enough resonance to endure for millennia. Later, when scholars study the layers, they may still find remnants of metal in the deep core, but for many generations, the lostness of the technology remains a mystery. Legends tell of gods once helping, of people being taught, and so the memory remains—veiled, adapted, sacred.

Sometimes, on cold nights when the wind carries ancient dust and the stars shine particularly brightly, signals still flicker across the desert horizon. Not all strangers stay; some leave, others linger, some return in cycles to observe, not to dominate. Those who remain become increasingly intertwined with the fabric of human life, some contributing knowledge, others withdrawing to the margins. The communities that emerge from that era carry a dual memory: that of the tools and that of the gods. They teach their children to honor the heavens while simultaneously building according to a plan that is no longer fully understood.

This is how pyramids are created – not as mere monuments to human mastery, but as the product of encounter: a formal smoothing of what was once alien and metallic. Millennia settle like sand on metal, on memory, on power. The ships evaporate their secrets in a layer of myth and dust, and what remains is the form, losing its function and becoming a symbol. And yet, hidden beneath the layers, technology remains – the scar of another sky, a legacy waiting to be discovered and to tear the world open once more.

In that first hour of encounter, when children laughed and priests bowed, something greater than any single culture began. The bond between stars and sand was woven. The alien pyramids laid the first lines, in metal and in memory, which humans would later call "structures of immortality." The gods had departed, or they had remained; it is difficult to say. But their traces, in the form of metal cones that would later mutate into pyramids, remain in the earth. And wherever humans build, the idea continues to grow, until the world itself inherits it and carries it on in its own name.

Chapter 1 - Arrival

The morning is the color of lemon fiber—bright enough to make the world seem friendly, but not so intense as to be blinding. In the kitchen of the small bungalow in Santa Monica, the air smells of roasted coffee and salt swirling in through a slightly open window. Raymond stands at the stove, a spatula in his hand, speaking in a voice so practiced it could soothe a cat. Melanie wears a breezy dress that makes her look as if she's just stepped out of the ocean, even though all she's done is make breakfast. Prince sits at the table, elbows on the wood, his fingers tapping the tabletop in a drumbeat. He's twelve and has that nerve, that frayed tension—not quite anger, not quite impatience. Skepticism clings to his gaze like salt to the rim of a glass.

Lisa sits beside him, a little girl with hair like dark silk and hands so still, as if they'd never broken anything. She's nine years old, and she's been part of this family for three weeks. Raymond always says "three weeks and a few days" because he likes precise numbers; Melanie simply calls the day "our new morning." Prince says nothing about the day. He looks at Lisa because that's his job—that's how it feels. He wants to know what's hidden in the eyes of the girl who is so quiet that even the clock on the kitchen wall seems to fall silent when she takes a step.

Lisa's eyes aren't simply brown; they're deeper than any ordinary color name allows. You get the feeling they read not just light, but stories. You can't quite describe how they see more without sounding like an exaggeration; and yet Prince sits there again and again, watching her gaze shift the contours of a moment. It lingers on a patch of air when someone laughs, as if testing the waves of laughter, and sometimes, when no one asks, she smiles as if she understands a joke the world is keeping to itself.

That morning, Lisa rummaged in a small bag and pulled out a crooked stuffed animal—an old, slightly burnt teddy bear whose eyes had been replaced at some point. She briefly stroked its fur, as if it were a ritual, and gave it to Prince to look at.

“His name is Mino,” she says, quietly. Prince takes the teddy bear, holds it as if he has to check it, as if it were answering a test.

“Mino?” he repeats. It sounds like a nickname that still needs to be awakened with a kiss. The bear smells of soap and of strangers’ memories. Prince doesn’t immediately return the smile; his skepticism shines through like handwriting.

"Why do you have that thing?"

Lisa looks at him with that calmness that sometimes makes Prince shiver. "He belongs to me in my dreams," she says. "And sometimes he wakes up." She doesn't flinch when she says it. That infuriates Prince, because his feelings can't be contained in lines; they tip like cards.

“This isn’t funny,” he wants to say, but instead he takes the bear, puts it on the table, and allows the plush toy’s face to be a small, awkward side dish to breakfast.

They're eating pancakes. Raymond makes them with too much butter, Melanie sprinkles berries on top. Lisa eats slowly, carefully, as if each bite is a compliment to the world. Sometimes she pauses, looks toward the door, as if she hears something that isn't there. Prince notices how she holds her tongue between her teeth when she's deep in thought, and he finds it as irritating as it is charming. Irritation, that's his compass: something draws him in and repels him at the same time. He understands that Lisa is different—that's one thing—and he feels the small anger growing inside him because this difference raises questions he can't answer.

After breakfast, they get dressed. It's a sunny early summer day. The street smells of freshly cut grass and engine fumes. On the way to the beach, the family walks in a small formation: Melanie in front, Raymond in the middle, Lisa beside him like a silent satellite, Prince on the side, chin up, as if scanning for falseness.

The Pacific greets them with a breeze that instantly clears everything up. Santa Monica has this ability, Prince thought even during the move: the waves blind doubts if you just close your eyes and smell the salt. The vendors have already set up shop on the pier; a man twirls cotton candy like clouds, another child kneels building a sandcastle as if they were the architect of a miniature kingdom. Lisa walks barefoot, holding her teddy bear's hand, and the way she digs her toes into the sand is as if she's remeasuring the world with each toe.

They walk silently along the water for a while. Prince watches as Lisa examines the shells, not with childlike collecting mania, but like a cartographer marking landmarks. Then she looks at him, fixing his gaze with the intensity of someone who doesn't need to ask a question because they convey it directly.

“You’re part of them?” she asks suddenly, as if she’s picked up on a thought in his mind. Prince flinches; the question catches him off guard. He says nothing, unsure if it’s a test.

Melanie smiles because she thinks Lisa is acting.

Raymond says something innocuous about the weather.

Later, under a shady palm frond, Lisa takes out her notebook—a small book with a yellow cover, its pages rippling with seawater that had been forgotten at some point. She sometimes draws in it with a pen that often leaves more scribbles than clear lines. In the first few days, the notebook seemed like a child's toy, but one evening Prince leafed through it because he couldn't shake the strange feeling that the pages told a story beyond a child's fantasies. Symbols, he wrote to himself then, that defied easy explanation: spirals that slid into crosses; small marks that looked like simplified constellations. Lisa doesn't notice him looking at the pages. She lets the pen circle in her hand as if tracing a melody only she can hear.

Something happens on the beach that seems like a small crack in the order. A bird, a gull chick perhaps, flutters among the driftwood with a broken wing. A man bends down, tries to pick it up, makes an awkward movement. People turn around. Lisa stops, her features revealing a mixture of pain and resolve. Then, quite suddenly, her mouth opens, little more than a whisper, and a breath escapes—not a loud, magic word, more like a breath, barely perceptible.

She goes over, kneels down, and gently places her hand on the folded feathers. Her fingers don't touch the bird forcefully, but as if examining it. Prince stands, frozen, the waves losing their roar in his ears. The bird snorts, its flapping less tremulously. A gulp, then a rising, and a turn, barely a wingbeat, a hovering in the air—as if an invisible thread had been rewoven. For the people who witnessed it, it was a small, miraculous movement; for Prince, it was a spark, a window that opened: Lisa could do things no one expected.

After this incident, a neighbor is crying—not an old man, but a young father with a toddler in his arms, the child having scraped its ankle in the sand. The father has tears in his eyes, not just from the pain, but because the fear that had plagued him throughout the night dissipates in a moment of purification. Lisa stands beside him, holding his hand, not letting go, but firmly, warmly, and Prince watches as this man slowly smiles, as if an inner knot is untying. Prince wonders if this is normal, if children do this. His stomach growls with a mixture of admiration and something closer to fear.

In the afternoon, they all sit on blankets. Raymond makes sandwiches, Melanie reads a blog on her tablet, Prince half-heartedly plays Frisbee with a boy from the street. Lisa sits among the blankets, her notebook open, drawing. Sometimes she talks softly to her teddy bear, as if it were going on a journey, and Prince feels his coldness melt away. Curiosity—that's the new word he discovers within himself, a feeling that doesn't reek of criticism, but rather of a hungry kindness. He wants to know, wants to understand.

Back home in the evening, the house becomes an aquarium of light. Raymond tidies up, Melanie dresses Lisa in an old T-shirt that's too big. Prince sits on his bed, the window slightly open, listening to the car bodies in the street. His thoughts revolve around two things: the way Lisa places her hands on those in need, as if she's not just comforting them, but also taking something away—and the notebook of symbols he still can't quite decipher. He gets up, goes into the kitchen, takes a sip of water, and finds Lisa there, at the kitchen table, her brow furrowed, her lips slightly parted.

"What do you think?" he asks, unusually cautiously.

Lisa looks up, surprised and open.

“I sometimes hear voices. Not words, more like colors. And images. Today there was a blue that tasted like salt.” She says this with the nonchalance of a child describing a favorite color. Prince felt this blue on the beach, as if a cloth were held between them. “And you?” she asks in return. It’s as if she wants to mirror his exploration.

“I think you belong here,” Prince says instinctively, and he experiences a clarity, as if drawing a line between things. Not because he wants to be the savior, but because he has decided: this is his business. Lisa looks at him, and in her eyes, this is no wonder, only relief. She places her hand on his, so gently that a split second later a warmth grows within him, like coming home.

The days coalesce into a series of moments: a dinner where Lisa suddenly tells a story no one has suggested; a morning when she wakes up and names a flower that exists only in an old book. Raymond and Melanie exchange glances in which worry and love mingle like two colors. Sometimes they whisper Latin phrases, as if trying to conjure stability. Prince observes them, and often he advocates a quiet silence, one he prefers to maintain because words name things the world doesn't readily accept.

One evening, when the city glittered in the glassy light of the streetlamps and the sea stretched out like tin, they sat on the veranda. A neighbor came by, an old man with wrinkled skin, who always collected stories of days gone by. He stayed longer than necessary, and when he said goodbye, Lisa placed her hand on his arm. The man took a deep breath, as if he had suddenly understood a great deal, then he smiled softly. "That's good," he murmured, barely audibly. "Good that you're here."

Prince looks at his parents, who are sitting beside him. He now realizes that while skepticism is a shield, curiosity is the key that can open doors one cannot see – doors into people, into moods, into that which the world has not yet fully become.

Prince lies awake at night. The sounds of the house, the breathless sea in the distance, the soft footsteps of sleeping people—everything seems like the capillaries of a living body. He thinks of Lisa and the things she doesn't explain. He thinks of the way she comforted an injured bird and of his father's weeping hands. He thinks of the notebook with its spiral binding, of Mino, the teddy bear, of Melanie and Raymond's eyes looking at him as if the weight of a decision rested on their shoulders.

Finally, he places his hand over his heart, as if to soothe it. Then he quietly gets up, goes to Lisa's room, and sits down by her door. The lamp casts a warm circle on the bed. Lisa sleeps peacefully, her notebook open on the blanket, Mino lying beside her like a sentinel. Prince watches for another moment and whispers, "You're not alone." It's not a grand, heroic gesture, but a promise, small and firm as a seed. Then he goes back to his room, lies down, and for the first time in weeks, he sleeps without the nagging pull of skepticism, but with a new, tender curiosity in his stomach—the curiosity of a boy discovering a world bigger than anything he's ever known.

Chapter 2 - Initial resonances

The next school day dawns with a gray sky, as if the world has decided to think in a color that defies immediate explanation. Prince cinches his backpack with mechanical precision, as if the order within it stabilizes his confidence. He barely slept last night; Lisa's words still echo in his mind, the image she projected onto his forehead—a blurred sea of voices—as if he had pressed it to his ear like a cold seashell. He tucks the feeling away in a mental pocket, one he only opens when necessary.

School Street is bustling with life: bicycle bells, an old woman with a bedsheet full of laundry, loud laughter from the café on the corner. Lisa walks beside him, with the bearing of a child who feels the weight of the world more than other children her age. She stops at a traffic light, as if there's something important to see. Prince watches as she inhales the air, closes her eyes briefly, and then, unexpectedly, places her hand in his. It's a light, casual touch, but it contains affection and a silent "thank you."

In the classroom, the morning is ordinary: blackboard, mouth full of chalk, the murmur of early morning conversations. Mrs. Alvarez, the class teacher, has a quiet way of organizing things that calms the children. She begins with the usual daily schedule—mathematics, a small reading project, drama in the afternoon—but beneath the murmuring, another sound emerges, a fluttering, which Prince barely registers because his eyes are fixed on Lisa.

Lisa sits very still, her hands in her lap, her eyes perhaps a little brighter than usual.

After an hour, she raises her shoulder almost imperceptibly, as if warding off a pulling sensation.

The commotion begins during recess. Two girls get into an argument over a borrowed ruler; words fly, a face contorts, an arm is raised, a nickname is hurled. Prince hears it from a distance, but for Lisa it's more than just noise—it's a tangle of anticipation, fear, shame, and the ever-present pulse of schoolyard dynamics. Something begins to stir in her chest: a pressure, a knot, as if a great deal of uncontrolled energy is trying to coalesce into a small flame.

She leaves the schoolyard as if drawn by a magnet: no fuss, no drama. She stands at the edge of the yard, where the trees cast shadows, and breathes. Her face changes: pale, then a tremor, until she gasps and presses her hand to her mouth. Prince is instantly at her side, the world slows down, his heart a dull thump. "Are you okay?" he asks, his voice possessing a protectiveness he hadn't thought possible before.

“I…” she gasps for breath, “it’s like… like all the voices are inside me at once. They’re pressing. My head is ringing.” Her eyes are moist, and not just from the November wind. Prince doesn’t want to explain; he wants to act. He takes her hand and squeezes it tightly.

"Breathe with me," he says, even though he doesn't know how. He's learning in that moment.

They breathe, deeply and in sync. Prince counts quietly to five, an anchor, as he'd read in an article. The panic dissipates slowly, like fog dissolving into wind. Lisa continues breathing, her hands clinging to his fingers, and for a fleeting moment their natural awkwardness vanishes—it's as if they've closed a window together, one that had been overwhelmed by too many images.

The teacher takes her to the office and gently offers a word of reassurance. "Perhaps too much break time, too many impressions," she says with the professional detachment that teachers sometimes maintain.

Prince sits beside Lisa and watches the adults talk. Miss Alvarez suggests speaking with the school psychologist. "Sometimes children have sensory sensitivities," she explains. "They have to learn to cope with them." It sounds plausible, but Prince knows Lisa's world runs deeper. He remembers the image she placed on his forehead days ago; he feels that words like "sensitivity" are close to the truth, but not the whole truth.

At home, sounds are perceived differently. A loud truck rumbles down the street, a garbage truck exhales its metallic breath, a siren wails in the distance—small, unexpected things that don't bother others tug at Lisa like thorns. This afternoon, an unexpected clatter of towels in the bathroom makes her nauseous. She retreats to her room, lays her head on the windowsill, and waits until the world regains its size and its peace.

Raymond immediately went on high alert. "We need to see a doctor," he said in the kitchen, while trying to salvage a cup of coffee.

Melanie takes a deep breath and calls Therese, a child psychologist in the area who works with play therapy.

“Play therapy,” she repeats, almost like a prayer, “we need someone who works with children and helps them organize the space around them.” She hangs up, writes down an address, and calls a colleague for recommendations. Her hands are quick, her voice a net reaching for support.

That same evening, they sit in Dr. Therese Martins' office, in a room arranged so that children don't feel like they're being examined: colorful cushions on the floor, shelves full of wooden toys, a corner with stuffed animals. Dr. Martins has eyes that wait patiently. She takes Lisa seriously, doesn't ask questions that sound like tests. Instead, she offers her colored pencils and lets her draw. "Red color?" she asks, pointing to a piece of paper. Lisa nods, without haste.

While Lisa draws, Dr. Martins speaks quietly with Raymond and Melanie. "Some children are extremely sensitive to external stimuli," she says. "They might perceive sounds as pain or air as pressure." She explains what sensory integration disorders are and how play, rhythm, and physical exercises can help the body reacquaint itself with the world. She also recommends ruling out neurological tests—an EEG, perhaps a brief neurological examination. Raymond nods, and Melanie takes notes. Both are relieved that someone is taking them seriously, but also anxious because tests could disrupt this peace.

Prince sits in a small armchair, his knees drawn to his chest, watching Lisa. She sits on the floor, legs crossed, pen in hand, drawing spirals, lines, a sense of waves. Every now and then she lifts her head, her eyes seeking his. He goes to her, sits down beside her, and without prompting, she places her hand on his forehead. It is a small, familiar gesture by now, that his heart expands without warning. He feels a pressure, as if someone is listening to him from within. Then he hears her voice, not loud, more like the sound of a distant glockenspiel.

“It’s like…” she says, her voice very quiet, “a sea. A sea that has voices. Sometimes the voices are nets and they pull. Sometimes they are rocks that hit me. I never know whether I should swim or hide.”

Prince feels the words like waves. It's not just a metaphor; images are actually forming in his mind: a sea composed of voices, each wave a conversation, a memory, a sound. It's overwhelming, and yet Lisa gently holds his forehead.

“Can you see the sea?” he asks, and in the question is contained the touch of fear that defines him.

“Sometimes,” she replies, “but it’s blurry. It’s not clear because all the voices are talking at once.” She presses briefly, as if stamping his forehead. “Don’t bother me,” she says then, silently, as if telling him the rules, “but be here when the waves are high.”

Prince senses this isn't just a request. He takes it seriously, as seriously as one takes a promise. He raises his hands, clasps them, and says nothing, because there are no words that can lessen the ocean. Instead, he looks for solutions: he asks Dr. Martins what can be done, learns breathing exercises, and brings Lisa a small piece of modeling clay to knead when the voices get louder. Melanie arranges an appointment for the EEG, and Raymond calls the insurance company.

The next few weeks are a choreography of small rituals. In the mornings, they drink tea together, and Lisa has a blanket she can wrap around herself when noises are too loud. Prince often sits next to her on the bus to school, pressing silence between them like a protective shield. Dr. Martins playfully teaches them how to connect their bodies to sound: a tapping game, rhythmic breathing, eyes focused on a single point to reduce the flood of noise.

Lisa is learning to open small windows in the tide. She's learning that not all voices are dangerous. With each day she practices, the sea becomes a little clearer. One afternoon, she accomplishes something that astonishes everyone: During recess, she remains calm when a girl approaches, her eyes flickering with panic about an impending argument. Instead of running away, Lisa breathes, looks at the girl, absorbs her energy, organizes it, and the girl exhales and suddenly laughs, as if a brief storm has passed. The teacher observes the whole thing with a frown that can't immediately tell whether it's a miracle or simply the product of everything they've learned over the past few weeks.

Prince watches, feeling both admiration and that old, clammy fear. He remembers the days when he sounded as if the world were a distant machine, its cogs turning unnoticed. Now he is part of the machine, his hands meshing with the gears, learning that restraint is sometimes the most effective action. He is less angry and more determined. His role is taking shape: he is not a hero saving the world in the style of a movie. He is a guardian, an Earth Lisa can lean on.

In the evenings, after a school session, after a practice, after a day spent breathing more than talking, they sit together in the kitchen. Raymond cooks pasta, Melanie pours wine, and Lisa draws. Prince sits opposite her and looks at the spirals in her notebook. He wants to interpret the spirals, wants to know if they can become a map: a map to Lisa's sea, a map to the way voices organize themselves. He asks her, "If your sea were a place, where would you swim?"

Lisa looks at him with the calmness with which a child guides an adult. “Not always,” she says simply, “sometimes I go to an island. It’s small, with a tree. There’s a chair there. I sit and count the color of the leaves.” Then she shows him a drawing—a small circle, a spiral, a dot. Prince feels an undefined joy that comes from the profound knowledge that through images and gestures one can approach a reality one cannot yet express in words.

The therapy is working. Slowly—slowly, like fertilizer taking root—Lisa is finding ways to cope. She's finding a way to hold onto an anchor in the midst of the storm. In the evenings, Prince practices breathing exercises with her and taps rhythm on his shoulder when the sea crashes against the shore of her inner world. Raymond and Melanie are learning to name their own fears and, as a result, become more careful with words that burden others with the weight of the world. They are learning to see Lisa not as a puzzle to be solved, but as a landscape that unfolds when one remains patient.

Yet alongside this cautious new beginning, something immense remains: the realization that Lisa is not only sensitive, but in some way different. The doctors treating her find no pathological cause. The EEG shows no clear epileptic activity; the neurologists are baffled, pointing to the need to consider emotional and social factors. It's as if the world holds its breath, refusing to label her.

On a still night, when all is asleep and only the city speaks with its drizzle, Prince takes out his notebook. He doesn't draw precisely, just circles, spirals, lines, like Lisa does. He writes a note at the bottom: "For Lisa. Guard the island. Preserve the tree." Then he puts the book down and looks toward the door of her room. He has the feeling that this life, her task, is not a one-time struggle, but a practice that unfolds over years. He takes a deep breath, and in that breath lies a promise: I am with you. I will stay. I will check in. I will protect.

Outside, a wave crashes against the pier in the distance, the sound like a faint applause in the night. Prince smiles softly into the darkness. Lisa sleeps, her hands around Mino, her breathing calm, the sea within her temporarily still. Tomorrow another day will begin, with school, with small storms, with practicing breathing, with drawing maps. But in this moment, under the glow of a streetlamp, the boy is ready to listen to the world the girl carries within her—and not to leave her alone.