3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: FINN Books Edition FireFly

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

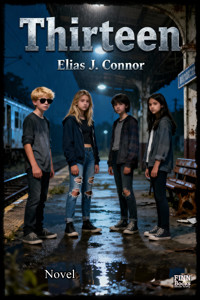

Thirteen years old—and already the leader of a gang of street kids. Jorn knows only the night, the dilapidated train station as his refuge, and the harsh logic of the ghetto. By his side: Nala, who seems stronger than she feels; Boris, who silently hides his wounds; and Rosita, who holds the group together with a sharp tongue and even sharper courage. What begins as a dare and a petty theft quickly spirals into a cycle of power, fear, and false freedom. Amidst stolen mopeds, gangs, secret longings, and the bruises of everyday family life, the four learn how thin the line between unity and disintegration can be. Love, loyalty, and betrayal lie close together—and every decision comes at a price. "Thirteen" is an uncompromising, gritty, and emotional novel about childhood on the edge: about the hunger for recognition, about friendships that are stronger than any family—and about the truth that teenagers experience when they are forced to grow up too soon.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Elias J. Connor

Thirteen

Dedication

For my girlfriend.

Muse, confidante, true love.

Thank you for being there.

Chapter 1 - The train station

It is night, and the train station isn't so much asleep as breathing differently. The lamp above the platform flickers as if someone with a feeble hand had poked out a long-boarded light. Wind whistles through the broken windows, a cold breath that carries scraps of paper and plastic bags like small birds. A dog barks in the distance, then the sound echoes through the empty tracks like a warning cry. Four figures move through the twilight, barely more than shadows in the moonlight; yet everyone who comes here recognizes their silhouettes. They are the children of the station, the owners of a ruin that is more home to them than any place with closed doors.

Jorn leads the way. He is thirteen years old, and his shoulders carry the bearing of an older man. His face is narrow, his jawline hard, his eyes dark as needles; he wears a jacket that looks too big because the sleeves slip off his hands, but that's precisely what makes him look taller. Coolness, they say, hangs around his neck like a scarf—he wears it with the self-assurance of a boy who has learned that poise is sometimes more important than food. Sometimes, when he looks in the mirror—if he even looks in a mirror anymore—there's a boy there who is left alone far too often. But he doesn't tell anyone that. The others prefer to believe the image he projects: calm, invulnerable, fearless.

Nala walks beside him. She's wearing a thick sweater and jeans, her knees ripped, as so often before. Her hair is loose, slightly tousled. She walks with firm steps, as if she's about to run, but her eyes keep returning to Jorn, as if they were a magnet, as if he were a continent and she the only person allowed to touch land. The corners of her mouth often play with a smile, but there's something else in her gaze: warm admiration, almost seamlessly intertwined with worry. She sees in Jorn not just the leader; she sees the one who stays awake when sleep is impossible, the one who has a plan, even if it consists only of courage. Nala is strong, but not without fear. Her strength is born of inner resilience: she has learned to get up, so she does.

Boris pulls his hood further down over his face. He's always a step behind the others, as if he doesn't quite want to belong, but he does. His eyes are watchful, often staring into corners where others suspect unrest. He speaks little. When he does, each word carries weight, like something he carefully gathers before spitting it out. His hands conceal something in a pocket—a piece of paper perhaps, or lead, or a small secret. Sometimes you can see the twitch of his lip when something gets too loud, when voices come too close. They are the echoes of a world that has hurt him. Boris carries wounds that aren't always visible, and silence is his armor.

Rosita is the last one. She always has her arms crossed. Her eyes are sharp as needles, her mouth a straight line that rarely softens. Her sarcasm is sharp, her humor mostly bitter, as if she were licking the salt of the earth with it. She's the one who kicks down a door when necessary, and the first to say what everyone thinks but no one else dares to say. She protects the group with a rage that is often not so much loud as it is persistent. Rosita bears scars, small, inconspicuous marks of a life she didn't ask for. She's angry, but she has an anchor in her mind: friendship means more to her than coolness. She stands up for it, often without a word. She's the youngest in the group, almost twelve.

The train station is their headquarters, a ruin with a name and a history. Trains used to roll here, people arrived and departed. Now walls gape, waves of plaster crumble away, and rails are covered in rust; moss grows between them, like grass on a former road. Graffiti in garish colors adorns the walls: slogans, names, hearts with arrows—the art of those who still want to express themselves, even when no one is listening anymore. In a niche stands an old, half-torn armchair, its fabric full of holes, the springs poking out like small white bones. Next to it, a plywood table, a glass, a few empty cans, a box of matches. On the wall hangs a poster of a long-forgotten pop star, his eyes like bleached glass. The smell of oil, urine, and grease mingles with the cold scent of the night; somewhere, water drips, making a monotonous, rhythmic sound that sounds to them like a conductor's baton.

Jorn stops, places a hand on the wooden couch, feels the rough surface, and lets his fingers rest there, as if testing whether what they claim night after night isn't just an illusion. Nala leans against the wall, her shoulders relaxed, as if she's found something there to hold her hand. Boris pulls his hood up, his eyes fixed on a dark corner. Rosita turns, surveying the room, looking for weak points, hiding places, ways to organize an escape if necessary.

“Not a sound today,” Jorn says. His voice is calm, a tone that conveys instruction and command, even though they are just friends. It is not the authority of an adult, more that of a boy who has learned that calm speaks louder than panic. “We’ll divide the field. Two over there, two here.” He nods and nods his chin toward the other side of the platform, where the shadows are thicker.

Nala tucks a strand of hair behind her ear.

“I’ll take the tower,” she says, “from there you can see the whole street.”

Her voice betrays excitement, but also pride; she likes the responsibility, even though she secretly hopes that her gaze will often fall on Jorn when he is not looking.

“I’m going to the tracks,” Boris murmurs. He tries to make it sound casual, but his eyes betray that he isn’t seeking the proximity to the tracks without reason: there he feels safe, as if the clatter of the rails were a heartbeat, making working with it less painful than thinking about it.

Rosita snorts, a cheeky noise.

“I’m staying here. If one of us gets knocked on, I’ll talk to him. Or at least shout.” She smiles briefly, only with one side of her mouth, and for a moment she is less angry than terribly alive.

They spread out as they have practiced a thousand times, without any adult ever directing them. The night embraces them as if they were old friends. They hear the city breathing: a car flickering in the distance, then vanishing again; footsteps so far away they seem almost imaginary; the occasional clink of broken glass dancing down under a sharp gust of wind. In this city that gives them nothing, every sound is either danger or confirmation that they still exist.

“If courage isn’t courage, then it’s madness,” Rosita says quietly, so that only Boris can hear. Boris nods without speaking. A flash of something like agreement flickers in his eyes, and then it disappears again.

Jorn thinks of his mother. He thinks of how she sometimes sits in the apartment with the shutters open, as if waiting for someone who never comes. He thinks of half-empty bottles, of papers and cigarettes, of the cough that echoes through his nights. Thoughts are rare, but as soon as they arise, they push the image of the train station into the distance, like fog blurs the contours of a ship. Jorn has learned to leave his heart in the trunk of a stolen moped—discreetly, at the bottom, as if it couldn't hurt anyone that way. He has learned that exhaustion and coolness are the same armor. And he has learned that sometimes a theft means less than a look that says: You are not alone.

Nala noticed this. She watched him when he was alone, and a quiet determination grew within her, barely more than a whisper. She wanted to fill the voids in him, didn't want to know if he wanted that. An invisible line hung between them: she was the one who wanted to give, he was the one who held on. But the closeness hurt, because Jorn never took anything called affection lightly.

Boris slowly pulls a scrap of paper from his pocket, folded and rolled up as if it were made of thin paper. It's a drawing. Not many people know that Boris draws. He's not the type you'd expect to be artistic; he's the type who keeps quiet. But his handwriting is different: on the paper is a drawing of a train station, not this one, but the way it should be—with sturdy windows, gleaming rails, and laughing people. In the drawing, the children are like figures smaller than themselves, but they're holding hands. Boris folds the picture and stuffs it away again, as if it were something too precious to expose to the night. No one asks. No one needs the answer he's trying to give.

Rosita slips a cigarette between her fingers and puffs, even though she knows it's not good. Smoking smells of rebellion, of something she imposes on herself to stay awake.

"If Rico comes by tonight," she says, "he'll get what's coming to him." Her voice is like a knife handle, "But nobody's going to catch us today." The others growl, they play along, the game they've mastered most perfectly: threatening, dazzling, surviving.

“We’re not kings,” Jorn says, “we’re just…” He searches for the word and finds none that could explain the gravity of his aggression. “We are what’s left of us.” That’s more philosophy than he wants to admit. The others nod. Everyone knows what’s left: a few coins, a broken chair, friendship that weighs more than anything they’ve ever owned.

A rushing sound. Footsteps. Unfamiliar voices, rough, untrained. The shape of a car recedes into the distance; two men get out, carrying what looks like cardboard boxes. The moon paints charcoal strokes on their faces, the strangers' eyes blink. Jorn barely raises his hand, gives a signal to Nala. She disappears, a shadow between the trains, and the next second she's at the top of the tower, a tiny dot watching the street below.

The night is no heroine, merely a sheet flapping in the breeze. Yet for these four children, it is an ally, sometimes their only friend. They have each other, and that is enough to share the cold, enough to break their fear into small acts of kindness. When the smell of burnt fat creeps through the station in the morning and the sun sends red shreds across the tracks, they realize they are merely figures in a greater darkness, but for the moment, they belong together, and that is what they deserve.

Jorn takes a deep breath. He hears Boris's faint rumble of his nose, which regularly appears in the night like a second voice, hears Nala's footsteps on the tower, which sound like a heartbeat. Rosita leans against the post, inhaling the smoke as if she were breathing in courage too. Within him is a mixture of caution and turmoil, a feeling that seems indifferent yet governs everything: a kind of vigilance one only has when one knows something is going to happen. Something that isn't pleasant. But as long as they are together, Jorn can face the world.

The night no longer settles over the group like a cloak; it becomes the space they share. And in this space, they invent rules and rituals, small acts of belonging. Boris, silently, pulls out a small tin and shares his ration of tobacco with Rosita. Nala fetches an old blanket, folds it carefully, and drapes a corner over the couch so someone can sleep if they get tired. Jorn gets up, walks to the exit, and gazes out at the streets of the ghetto as if scanning the entire neighborhood. He thinks of nothing, and of many things at once. He thinks that this train station is not only his hiding place, but also the last bastion of something like family.

As the wind picks up and the smell of rain fills the air, they hear the scraping of tires on the blackened road. A bus, a little further away, rattles the asphalt. Jorn takes one last look. His voice is soft as he says, "We'll stick together." It's not an order, not really. It's a promise, whispered, so that it's meant only for the others. Nala smiles, briefly and fleetingly, and in the gesture lies a future yet unnamed. Boris nods, Rosita pulls her jacket tighter.

The night accepts them and gives them nothing back. But in this acceptance lies a kind of home, a home they have when everything else abandons them. They stay, like a flock of small, hardy birds that cannot fly but rest together. The train station is their headquarters, their kingdom. And amidst the broken city that won't let them go, they cling to one another.

Morning creeps over Kölnberg like thick smoke, as if the houses had decided to sleep longer than the city. The first rays of dawn strike furrowed facades, balconies, and worn curtains that seem more shy than protective. Scents seep from the apartments: coffee, grease, sometimes something sweet, often just the bitter memory of what was once sustenance. Paper bags, a bicycle without a front tire, and cigarette butts litter the streets, and pigeons peck at them as if they were the only ones who still have anything to do here.

The four go their separate ways. It's a movement they perform effortlessly—a familiar ritual, deeply ingrained in the ghetto. They know the shortcuts, the crooked staircases, the garbage cans, the places where guard dogs bark, and those where the neighbors only appear after something has happened. They move like knots in a network whose patterns they have long since deciphered.

Jorn walks alone down the narrow hallway to his apartment. The stench of burnt food and cheap cigarettes hangs in the air of a hallway where years of wear and tear have dulled the walls, worn smooth by fingers and bumps. His apartment door stands ajar, as if it had never been properly closed. He pushes it open—not furtively, not proudly, just out of habit. Inside, his mother sits at the table, a figure both asleep and awake: wrinkles around her eyes, an empty coffee cup with an oil ring at the bottom. Her hair is stringy, her face like a map from which paths have fallen. Her arms are outstretched, her hands still, as if she is counting something within.

Jorn stops in the doorway. He clears his throat, a small noise that no one would notice. His mother doesn't look up. Her eyes are fixed on a crumpled television screen, silently playing out something that could have ended days ago. She takes a drag on a cigarette, her fingers practiced, the movement so automated that one might think she no longer has a body, only habit.

“Mom,” Jorn says, and the word has the harmlessness of a letter falling into an empty mailbox. She doesn’t register the sound. He takes a step closer. “Mom.”

This time her gaze glides past him as if past a ghost. She blinks as if thinking of something, a bill, the color of the walls, the time she cannot turn back.

"Is... anyone there?" she murmurs, more to the sounds than to him. She stands up—slowly, heavily—but doesn't go to him; instead, she remains at the table, as if she has to display a physicality that is no longer supported by anything.

Jorn feels the emptiness like a weight. He has grown accustomed to this invisibility, to the feeling that his existence inspires no expectations. He steps to the sink, starts running the water, listens to the dripping like a rhythm that grounds him. His fingers tremble slightly, no more than necessary. He searches for words that might force her attention, but he knows there is no sound stronger than the indifference raging within her.

“I wasn’t gone long,” he says, as casually as possible. A small experiment, like a test to see if reality still responds.

His mother shrugs.

“Don’t worry about it, son. Breakfast’s over.” She pulls a pack of cigarettes closer, as if that would replace a meal. It’s not malice that drives her; it’s demotivation. The world has made her hungry and given her nothing in return. Some days she doesn’t even have the interest in a name. Jorn sits as if gauging the heat of this indifference, picks up the coffee cup, feels its sticky rind, and suddenly he’s a child again, and empty at the same time.

He thinks about how things used to be—if they ever were better. A father who rarely comes. Bills clinging to the window like dark clouds. No one to ask how his day was, no one to stand up when he arrives alone. In this lack, another kind of closeness grows: the closeness to Nala, Boris, Rosita. The kind that stays because they reciprocate his feelings. There, at the train station, he isn't invisible. There, his step means something; there, his gaze means something. But at home, he's just the memory of a missed duty.

Nala, on the other hand, walks through narrow streets, past playgrounds where the sand is gray, where children have bricks instead of toys. Her home is one of those apartments with a balcony from which ropes hang, laundry dancing in the air. Her mother is still in bed; she hears the radio, its voices growing weary before they're even awake. Nala puts down her backpack, runs her hand through her hair, and her gaze strikes the apartment door like a hammer, the bricks, something that gives her nothing. It's not exactly rejection she feels; it's the feeling that no one puts down roots here. Her mother barely notices her. Perhaps that's how it's meant to be—less questioning, less responsibility.

"Were you outside?" the mother asks without getting up. It's not a reproach, more a profound weariness that can turn questions into threats.

Nala simply nods, and that's enough. Papers lie on the table, none of which are important to her life. Nala sits down, reaches for a piece of bread that's dry, but at least it's something. Her fingers are rough, as if she'd just been handling things not meant for children.

Boris arrives at his apartment, a two-room cell where the lamp hangs from a chain and the walls have cracks that look like roads. His mother isn't there; his father apparently isn't either. A note with a phone number no one calls anymore is stuck to the wall. On the coffee table lies a box containing old notes and bills. Boris puts down his bag, goes to the window, pulls the curtains back a little, and looks out onto the courtyard where a trash can reigns supreme. No one calls his name. The silence isn't surprising; it's expected. Sketches hang in his room, a few pencil drawings, lines that show how he sees the world—not as it is, but as he wishes it were. He clasps his hands, looks at the drawings. Not a sound from the outside. It's as if he's breathing in the enclosed space, filling the air with his own intensity.

Rosita finds no one at home when she enters her apartment; the hallway smells of hot grease, as if there had been a final feast in this kitchen. She throws her bag into the corner and collapses onto a sofa that has seen better days. Her mother is out, as always, busy some night. Rosita rolls her eyes, gets up, grabs a can of beer from the refrigerator, opens it, and takes a sip as if it were just water, as if it were just the ritual that could make the morning more bearable. She thinks of Boris, of his silence, of his drawings, and something warm and soft spreads through her—like a promise or a debt. She knows she's tough, but she has a softness that she only cautiously reveals.

At the end of the morning, the four of them meet again—not at the train station, but in a narrow square that serves as the heart of Kölnberg. An old kiosk sells cigarettes and lukewarm coffee. The owner gives them a brief nod; she knows their faces, their routines. Sometimes it's astonishing how so little attention can lead to such carefree living. No one asks if they need anything. No one asks if they're ill. That's precisely the point: in their families, they are nothing more than fixed opinions, things that simply exist. It's not a reproach; it's an absence that is as normal to them as the railway track leading out of the station.

"What are we doing today?" Rosita asks as she sits down on a low wall. Her voice crackles like old leather. It's not a question about a plan, more of a test to see if anyone will answer.

Jorn leans against a lamppost, looking down at the shoes. His fingers twirl a coin between his thumb and forefinger, as if weighing the possibilities of the world. "We're looking," he says finally. "We're seeing who's outside." There's something definite about his voice, something that rises from the silence; not loud, but firm.

Nala steps closer. “If we do nothing,” she says, “this will do us.” She looks in Jorn’s direction, her eyes heavy. “I don’t want this to be the end of us.” It’s not an accusation, more of a plea, almost a command, coming from a deeper place. Jorn looks at her, and for a moment their eyes are merely tentative glances. The feeling between them is like a rope that must not be cut.

Boris fishes a small bag out of his jacket and lays the drawing flat on the stone beside him. Rosita leans forward, looks at the drawing of the train station, and for a moment her eyes soften. "Not bad," she murmurs. "If we could rebuild it..." Her voice trails off. The idea is laughable, almost disrespectful, but in all of them, something like longing flickers. The drawing doesn't just show the train station; it shows people embracing. It's just a pencil sketch, but it's also a suggestion: to live differently than now.

They talk. Not about grand plans, not about the future in the way adults do. They talk about things that are real and tangible: who saw them, which muggers are around, whether anyone will stop them later today. They speak with a language that is short, pragmatic, like the sequence of steps one takes before robbing a store or stealing a motorcycle—and yet they don't say aloud what they think. It's almost as if they shy away from words because they believe that if they are spoken, they will become truer and they will no longer have a choice.

The neglect they experience at home shapes them, but it doesn't just unite them in pain. It's also a catalyst, a necessary void in which they find each other. Without this lack, they might be mere individuals, perhaps children among many. With it, they form a structure. The train station is their center, the drawing their dream, the advice of their gruff affection their law.

“We have to be careful,” Boris says suddenly, his voice deep, as if he were swearing something. “Rico won’t let up.” His eyes scan the square as if he sees what others don’t: lurking glances, passing silhouettes. The others nod. They know the name, they know the face, they know about the threats Rico sends out like knife thrusts.

Jorn finally folds the coin and puts it in his pocket.

“Then we have to be faster,” he says. “And smarter.” It’s a sentence barely louder than the wind, but it carries a sense of obligation. He looks into Nala’s face. “And if need be, then we’ll do what needs to be done.”

Words that act like a release valve. Nala looks at him, openly, and it's as if she wants to follow him – wherever he may lead.

They disperse to carry out various tasks: a few errands, a few glimpses into the alleys. The time of day calls differently than the night, but under the sun the city doesn't change fundamentally. It's only brighter, clearer in its fractures. The four go their separate ways, each in their own direction, and yet invisible threads draw them back to the same place. Each of them takes the world with them, puts it in their pocket, folds it like a cloth, to unfold it later.

Jorn pauses briefly, looks at his hands. He thinks of the invisibility at home, the weight of indifference, and he thinks of Nala, of Boris, of Rosita—of the people who don't miss his presence. A faint smile plays across his lips. It's not big, not very convincing, but it's there: a spark that he belongs to someone. And perhaps it's precisely this feeling that drives him, that will one day make him run in the wrong direction. But now, in the early morning, the air tastes of possibility: of rebellion, of days when things might be different. The city is heavy, but for the moment, he carries it.

Chapter 2 - Daylight

The bell is now just a distant echo as Jorn pushes open the school door. The hallway smells of stale sweat and hot cardboard; the walls are plastered with tips on how to deal with stress, as if notes and sentences were meant to fill in the gaps in the children's knowledge. He shuffles in, his backpack half-slung over one shoulder, his shoes flapping. He doesn't care that class has already started—school is a formality to him, a place where time passes. The lessons are just filler; life lies outside.

"There you are at last." Mrs. Köhler, the class teacher, has her hands on her hips, and her voice has that thin sharpness that teachers adopt when they want to show they are more than just educators: authority. Her hair is tied back in a tight bun. She looks at him over her glasses, and for the first time, a hint of anger filters into the indifference Jorn usually exudes. "Sit down, Jorn. We're just starting."

He nods, makes a half-hearted gesture toward an empty seat—directly opposite the window, where it's easiest to drift off into daydreams. A boy from his class, Mehmet, glances at him, a look that lingers longer than necessary. Mehmet is one of those classmates who rarely follow the rules, yet frown when others don't. Today, there's something about him that smacks of revenge: A few days ago, Jorn shouted something at him, something stupid that pierced his pride like a small prick. Today, the crackle in his posture sounds like a match.

The hour passes in a haze of formulas and names, without foundation. But the glances directed at him are a sharp knife, rattling between the pages. During the break, Mehmet suddenly stands before him, his hands no longer in his pockets.

"So you think you're cool, huh? Always running away, always talking, and nobody says anything? You think you're somebody?"

Jorn looks at him, his expression calm.

"What do you want, Mehmet? It's just school. Chill." His tone is casual, his words short, seasoned with the slang that the streets give their children as armor. It's not a solemn sentence, more of a gesture that says: I'm not afraid of you.

"You think you can do anything," Mehmet snarled. "You steal people's ridicule and grin while you're doing it."

A laugh from the side, a teasing voice, and the tension mounts. Two others from the class approach, shoulders broad. In seconds, the circle is smaller, the breath hotter. A blow lands—short, impulsive. Jorn doesn't back down; his posture is like steel, hardened by nights and taunts. He strikes back, automatically, as if his body were used to fighting back. It's not a calculated fight, just a reaction. The class falls silent. A few students film with their cell phones because acts of violence promise clicks; others look away, as if trying to avoid guilt.

The director, Mr. Breuer, appears as if he'd overheard the commotion and brandishes an office key like a trophy. He's tall, with a paunch that somewhat diminishes his authority, and a mustache that gives him a serious air. He has a habit of breathing deeply, as if he needs to calm the world so it can function. "Jorn," he says in a voice that attempts to sound the rule, "please come with me to my office."

In the hallway, conversations ripple through the air, like a passe-partout: eyes flicker, glances follow. Jorn follows the director, not hastily, but rather with a serene gravity. His heart beats calmly, but something fidgets in his stomach like a beetle, against the cracks of his composure. The glass of the office door reflects his face; for a moment, he seems a stranger to himself. Mr. Breuer sits down behind his desk. A poster flutters in front of the windows: "Respect is fundamental," and the letters seem hollow.

The director taps the table.

"I've received complaints about a fight in your class. Boys fighting, that's unacceptable. I have a duty to inform your mother, Jorn. Do you have anything to say about it?"

Jorn flinches.

“Go ahead and do it,” he says, with an indifference that reeks of cynicism. “My mother gets every call. It doesn’t bother her.” His voice sounds a bit like a throw. He isn’t afraid, not really. What’s the point of the call? Perhaps a platitude, a brief reprimand, then silence again. The director leafs through documents as if searching for the appropriate cabinet statement.

“Aren’t you afraid of the consequences?” Mr. Breuer doesn’t ask it aloud, but the question hangs like a heavy accusation. Jorn looks at him, fixes his gaze, and then a short, cutting laugh escapes him.

"Honestly? What am I supposed to get? House arrest? I just call it training. I'll go out. And if things get serious, I'll take it. No problem." His tone is cheeky, a minor storm of provocation.

The director makes one last attempt to make a difference. “You have to understand, Jorn, there are rules. If we allow something like this…” He holds out his hand, as if rules were tangible, as if he could lay them on the table. Jorn raises an eyebrow, the corners of his mouth harden. It isn't cowardice, but a test: Who still holds power here? His way of speaking is the language of the streets, the clothing of the underground; it is a response to the meaninglessness he encounters daily.

“Call the cops,” Jorn finally says. “Put handcuffs on me. I can see what good that'll do.” The threat isn't loud, but it's powerful. Mr. Breuer stands up, searching for a moment for authority protected not by numbers, but by a voice.

"That's not the way, Jorn. I want you to take responsibility."

Responsibility. A word heavy as lead, one that should never weigh on empty tables in homes. Jorn purses his lips; a warm mockery lingers in his gaze.

Outside in the hallway, the students murmur. Jorn is sent back to class with orders to report to the headmaster again after school. The teacher offers a silent prayer, as if he himself were a guardian, clinging to a spark of responsibility. Jorn smiles, half-heartedly. He can live with it; in a way, it's routine. Offenses, school, headmaster, petty punishments that leave no mark. His world is resilient against these small blows, forged from nights when pain operates by its own rules.

Rosita and Boris arrive late. They stroll into the classroom, not hurriedly, more like two people who could easily use another morning. Rosita brings the raw humor with which she tears down walls. "Was there a traffic jam?" she asks, the words like a provocation to the school's noisy clockwork. Boris sits down quietly, pulls out his notebook, as if punctuality were a mathematical unknown he can solve if he only finds the right formula. They both know that the school rules have a different currency for them. They have little respect for a system that never had any respect for them.

Nala is missing. Her absence creates a palpable void in the air, a silence as if an instrument were missing that would otherwise carry the melody. The row of seats opposite remains empty, a chair like a heart without a pulse. The teacher doesn't ask any questions; numerous absences are considered insignificant ripples. But Boris glances up briefly, his eyes narrowing. Something inside him calls out, a small worry that refuses to be put into words. Rosita guards her brow, as if the tension might cost her something. Jorn, however, shrugs and thinks: perhaps she's sick, perhaps she's at home—or perhaps she has other reasons. With that, he closes a window that usually let in fresh air.

The lesson continues. During the break, they retreat to the schoolyard, a small park of concrete and rusty benches. The boys from the other class tease each other, tossing words like tiny darts. A few younger students look up, intently, as if violence were being taught practical lessons. Jorn stands with his hands in his pockets, a picture of calm. He says nothing about his conversation with the principal. His weapon against loneliness is his cloak of serenity. Rosita looks at him, senses that something is different.

"You were at the director's office?" she asks, directly, without beating around the bush.

Jorn grins.

"Sure. Old rubbish. Must be my charm." His voice is sharp, and they laugh because laughter is a protective layer.

But the atmosphere is lighter than before. Without Nala, a certain warmth is missing. The school silently drifts through the day with its indifference, and the children, who don't have much, quickly learn how to generate attention themselves: with jokes, with dares, with petty offenses. The afternoon becomes a time of possibilities. The city bathes the streets in flickering light; the smell of frying oil and gasoline wafts through the alleys. Rico is mentioned. Runaways speak the name as if it were a lid beneath which danger simmers. The children know that he is tightening his net, but each has their own reasons for not submitting to him.

“We’ll meet at the station tonight,” Rosita says as she leaves the group. “Everyone.” Her voice is sharp, and her gaze holds the logic of a warrior. “We need to discuss what we’re going to do.” This isn’t a harmless suggestion. It’s a summon for decisions. Boris nods. Jorn doesn’t ask, because he knows it will come to this. Nala isn’t there, but inside him, her empty chair stirs threads. For a moment, he sees her before him, climbing the stairs, her shoulders slightly hunched forward, and then the image fades.

The afternoon hours pass like a series of small battles: bank cards, insults, a cell phone theft on another street, which they witness two blocks away. Jorn remains on the outside, a mixture of distance and curiosity. He feels a restlessness that keeps him awake at night: a thirst for more—for attention, for power, for the feeling that his actions matter. He has briefly felt that power when he steals mopeds, when the engine groans beneath him and the speed takes his breath away. That power is sweet and dangerous. It opens up new spaces, but it also sends him to places from which he doesn't know if he'll ever get out.

As school ends, the class breaks up into small groups. Some head towards the city center, others to their apartments, locking their doors as if they were small fortresses.

Jorn, Rosita, and Boris walk together, their school routes their old backstreets, which they know like the back of their hand. Above them, the sky turns coppery red; the ghetto is preparing for the night, which always has its own rules. The question of what to do hangs in the air, and although it remains unspoken, they know that the evening will bring decisions they will find difficult to reverse.

They arrive at the train station, and the heart of the neighborhood beats to its familiar rhythm. The couch, the table, the graffiti, everything as usual. An empty space; yet suddenly the air feels thicker. It's almost as if they're approaching a threshold. Jorn stands in the middle, looking at his friends.

“You know what Rico does,” he says. “He causes trouble—for all of us. We can either do nothing or we do something.” His voice is no longer fearful, just clear. Rosita clenches her hands. Boris breathes shallowly. They stand there, three figures, weaving a plan whose threads they could pull into darker corners. Nala’s absence remains a blunt void in the middle.

“If Nala doesn’t come,” Boris murmurs, “we should look for her.” His voice is quiet, but there is deliberation in it. No one objects. It is perhaps the first moment in which concern is louder than the instinct for self-preservation. Jorn nods, but his thoughts have already taken a different direction: the possibility of reacting, of attacking, of not just being a response, but an action.

Night draws near, and with it come decisions with no return. The four are still children, but within them, the spark of adulthood is igniting, however tenacious and misguided it may be. They are a unit, forging their own plan, and in the void left by Nala's absence, a resolve takes shape—dangerous and luminous at once. The city breathes, and they breathe with it, ready to take the next step.

Evening creeps over Kölnberg like thick wax. The lamps behind the windows cast yellow panes of light onto the concrete facades, and the sky is so overcast it looks as if it's been wiped with a rag. Jorn pushes open the front door, the footsteps of the stairs echo briefly, then all is silent again. On the third floor, his mother's apartment lies like an open book, its pages softened by the rain. He closes the door behind him, drops his backpack into a corner, and hears the soft clinking of a bottle in the kitchen.

His mother sits at the kitchen table. The table is covered in ash, a pack of cigarettes lies open, next to it a half-empty bottle that, in the dim light, looks like a glass with no future. Her eyes are glassy, her lids heavy. The cigarette hangs between her fingers as if it were a straw from which she must draw her last breath. She doesn't look up when he comes in. It's a habit, this not seeing; something he's experienced so often that it hurts less than it used to.

"Well?" she says, without raising her voice. The voice has the indifference of a machine that is still running, even though no one is controlling it.

Jorn stops in the hallway, his hands buried in the pockets of his sweater. He waits a moment, half in anticipation, half out of ritual, before murmuring, "I'm going to my room." It's absurd that he says this, because she knows; she doesn't know much, but she knows he won't be there long. She barely nods, her head remaining bowed.

The apartment smells of stale cigarettes, grease, and sweaty clothes. Plates are piled high in the kitchen; the refrigerator is almost empty, just a sliver of sauce floating in a plastic container, looking like a small, sad island. No smile, no hello, nothing to signal: You belong here. It's as if Jorn is a guest who could leave at any moment. He closes his bedroom door almost tenderly behind him, as if trying to shut out the noise of the apartment.

His room is small, a space between the walls that is his only true home—and yet even here there are few possessions. An old bed, a lamp, a poster on the wall that evokes memories of something younger: a motorcycle, black and shiny, a symbol of something faster than himself. On the desk lie a few notebooks, a crumpled shirt, and in the corner a small bag containing things that no one cares about: a few screwdrivers, an ignition key without a match, a scratched watch. Jorn throws himself onto the bed, stretches out his legs, and looks up at the ceiling. The wallpaper is peeling in one spot, revealing the gray plaster beneath—that, too, is a kind of story: everyday life torn open.

He thinks about that morning, about school, about the headmaster, about the snub he provoked there—an elegant, empty triumph. It's not rebellion; it's a test. How far can he go without something important breaking? And beneath it all, something else throbs: the absence of his father, the silence, which is no longer an echo, it's a space. His father lives somewhere far away, in another city, an address without a name, a man who never arrives, whose voice fades into the days. No phone call, no visit, only the imprint of his disappearance. Jorn feels it like a coldness radiating from his hip, always there, too much and yet empty.

He reaches for a bottle half-buried under the bed—a small bottle of cheap alcohol, a memento of nights when the streets disgusted him and the cold was unbearable. He takes a swig. The taste is sharp, warm, and unfamiliar, and for a moment something glows within him: a feeling of distance that is no longer so piercing.

He knows that it is not a cure, only a numbness that settles like a blanket over his thoughts.

A knock on the door is as quiet as a question. He raises his head.

"Jorn?" The voice is Nala. It sounds as clear as ever, sometimes too firm, as if she has to hold on to something so it doesn't break. He pulls the door open. She stands in the hallway, still wearing her coat, her hair disheveled, her eyes alert. She acts as if she's just on her way, as if she's "picking him up," as she often says. But there's something else in her eyes: this lingering, this yearning to be near him, as if that nearness were a light that warms her.

“Hey,” she says, as if she’s just saying hello, though the word is heavy with meaning. She smiles, a small, crooked smile. Her hands are buried in the pockets of her sweater. “Everything okay?”

Jorn shrugs. "Sure." He says it so routinely it's almost a habit. Sometimes it's easier not to get drawn in. "Come in. Want a coffee?"

She shakes her head. "No. I just wanted to look." She enters, takes off her shoes, and sits on the edge of the bed. The blanket rustles as she moves. For Nala, the room is familiar territory. The four of them have shared things here, secrets, nights. She knows the spots under the bed where old bags are tucked away, knows the stain on the mattress that never quite disappears. She sits there, and the air between them fills with the weight of unspoken words.

Jorn watches her. Her face is soft, backlit by the hallway, her eyes shine, and he knows she's searching—for something that isn't his fault: for support, for a sign that someone will stay. He feels it like a tug in his chest, a tiny pain he usually covers with derision. But today, the sarcastic paper stays in his pocket.

“You weren’t at school today,” Jorn says, sounding a bit more accusatory than he intended. But Nala doesn’t respond—no explanation, no justification. Jorn decides to leave it at that.

"Have you been traveling a lot?" Nala asks after a while, as if she wants to put the evening into perspective.

“Here and there,” he replies tersely. He puts the bottle down, turning it over in his hands. His fingers are still, the movements mechanical. “We were at the train station.” He says it as if it were no big deal. For him, it’s the center, the heart, the place where they stick together, where his presence carries weight—a contrast to what home is like.

Nala looks at the bed, her fingers clasped. "Rosita said we should get together tonight. She said we need to see something, decide something." Her gaze meets his. "Boris... is quiet. He's worried." Her voice drops, becoming smaller, as if carrying something she doesn't want to say.

"Rico," Jorn says simply. The word is like a shadow, brief and without any background noise. "He puts on the pressure." That name again—a promise of trouble. Jorn feels the tension in his body like an electric current thumping in his shoulders. Rico is the type who cuts off paths, sets boundaries, and uses threats. For boys like Jorn, he's a benchmark: give way or fight back.

Nala pulls her legs up, wrapping them in her arms. "I'm scared," she says so quietly that the words barely have a chance to leave the room. "Not of him... but of you..." She trails off, searching for the right tone. "That you'll change. That things won't stay the way they were."