26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

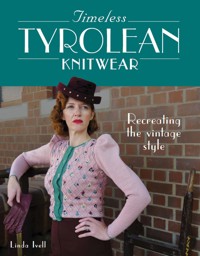

The passion for Tyrolean-style knitwear has endured for nearly one hundred years and it is still as popular today as when it first appeared in the early 1930s. Timeless Tyrolean Knitwear outlines the key techniques associated with the style and offers inspiration and guidance for creating your own vintage-inspired designs. Coverage includes an introduction to the origins and inspiration for Tyrolean knitwear and the defining characteristics of the fashionable style plus advice for working from vintage knitting patterns and adaptations for the modern knitter. There is a guide to vintage yarns and their modern substitutes and a Pattern Collection of thirteen knitting patterns adapted from vintage originals dating from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, some published here for the first time. Finally, there is an exclusive, new design offering a choice of vintage Tyrolean features and shapes to use as a 'menu' of inspiration for creating your own individual piece.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 387

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Linda Ivell 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4115 6

Cover design: Sergey Tsvetkov

Photography: Clio Potter

Model: Annie Cullen

CONTENTS

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

1 The Origins of the Knitted Tyrolean Style

2 Mastering Vintage Yarns and Patterns

3 Techniques for Working in the Tyrolean Style

4 The Pattern Collection

1. The Edelweiss Jacket

2. June Clyde Sets a Fashion

3. Annie’s Jacket

4. The Tyrolean Needlewoman Jacket

5. The Evergreen Jacket

6. The Hollywood Comes to Broadway Waistcoat

7. A Warm Red Cardigan

8. The Lilli Bolero

9. Forties Favourite Cardigan

10. A Heartfelt Waistcoat

11. Knitted for Best Jacket

12. Clio’s Cardigan

13. Cosy for Cold Days Cardigan

5 Creating Your Own Tyrolean Knitwear

Flowers for Laura

Endnote

Appendix 1: Crochet Stitch Guide

Appendix 2: Knitting Needle Size Conversion Chart

References

Suppliers

Index

ABBREVIATIONS

alt.: alternate

beg.: beginning

ch.: (see crochet st. guide, Appendix 1)

dc.: double chain (see crochet st. guide, Appendix 1)

dec.: decrease (by working 2 sts. tog)

foll: following

inc.: increase (by working twice into same st.)

K: knit

MB: make a bobble (instructions as in each pattern)

P: purl

patt.: pattern

psso: pass the slipped st. over

rep fr.: repeat from

sc.: single chain (see crochet st. guide, Appendix 1)

sl.: slip

st.: stitch

st.st: stocking stitch (1 row K, 1 row P)

T2B: twist 2 sts. (see explanation under ‘Stitch Grids’, Chapter 3)

T2F: twist 2 sts. (see explanation under ‘Stitch Grids’, Chapter 3)

tbs: through back of stitch

tog.: together

trb: treble stitch (see crochet st. guide, Appendix 1)

wl. fwd. / w.f.: wool forward

w.r.n.: wool round needle

yf: yarn forward

yo: yarn over needle

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My gratitude extends across the globe, and to so many whose support has been infinite.

There are three incredible women I want to thank very especially, from the heart, for the part they have played and their talent, patience and love:

• Annie, I can never thank you enough for being the perfect vintage model, for your warm friendship and for the very special magic you bring with you.

• Clio, my lifelong friend and talented photographer, for bringing your remarkable flair and understanding of my vision in creating these stunning images.

• My Laura, my daughter, my angel, you have watched, encouraged, believed in me, kept me focused and inspired me with your sensitive creative insight. I am blessed to have your love all around me.

Huge thanks to Cygnet Yarns of Bradford for their incredibly generous support of the book, providing such beautiful wool and encouraging my endeavours.

Very special thanks to the wonderful staff at Gloucestershire Warwickshire Steam Railway, who were so welcoming and accommodating to us at Broadway Station in Worcestershire, for providing the perfect vintage setting and for arranging the glorious sunshine.

To the many friends and supporters who have helped me put together the collection of patterns and originals:

• Karen Creed and Rosie Gleave for the beautiful treasures of original vintage knitwear, and to Gabriella’s LilyMothVintage for some fabulous Austrian buttons.

• Teresa Young, Chris Gough, Judy Dodson, Sue West The Vintage Knitting Lady, Deb of Juandah Patterns and Carole Tidy of Blackwater Vintage Knits, for drawing on their collections of original patterns.

My thanks also to:

• Heidi Cartmell for her expert post-production of the images.

• The Knitting and Crochet Guild, and especially Barbara Smith for help with copyright and sources.

• The Millicent Rogers Museum in El Prado, New Mexico for their dedicated help in finding the perfect photograph of the great lady in her Tyrolean home.

Very special thanks and heartfelt appreciation to The Crowood Press, who first lit the fire for this book and fuelled it with encouragement through one of the most difficult years our world has known.

I would like to dedicate this book to my knitting angels, the one who taught me long ago, and the one who has encouraged my passion all her life.

CHAPTER 1

THE ORIGINS OF THE KNITTED TYROLEAN STYLE

The Face that Launched a Thousand Tyrolean Hats

When Elsa Schiaparelli revealed her first knitted Tyrolean hat in 1933, the innovative and lovable enfant terrible of the fashion world caused quite a stir. Even as a renowned fashion designer to the highest society ladies, she could never have predicted then that the style she launched would continue to influence distinctive knitwear into the next century; yet here we are, with every successive decade contributing its own contemporary interpretation of Tyrolean style.

By the 1930s knitted garments were becoming accessible to everyone who could knit or was now learning the skills, and were no longer the sole preserve of the privileged elite buying from exclusive couturiers. New and experienced knitters were encouraged by a growing variety of publications aimed at promoting the craft as one which was available to all, and from these we can learn about the timeline celebrating the new Tyrolean craze that swept through fashion and especially knitwear.

Fashion advertising and promotion in the 1930s focused on famous people and titled aristocratic ladies to endorse products and styles. The illustrious names associated with the first interpretations of Tyrolean style include film stars, society belles, vanguard couture designers, even royalty, all attracting public attention through the press and fuelling the desire to imitate their style (something still so familiar to us today).

The earliest ‘Tyrolean’ pieces – mostly hats – date as far back as 1897, appearing in drawn illustrations in the most influential magazines, including Vogue on both sides of the Atlantic. This reflects the growing interest in Alpine fashions, and notably with skiing for the wealthy at their elite winter sports playgrounds. In 1924 Vogue illustrated a charming felt cloche by Reboux1 designated as Tyrolean, and by the early 1930s they regularly included features such as ‘Going Tyrolian’2, which celebrated the popularity of Tyrolean themes in theatre and light opera. The delightful yodelling headline ‘Oh lee lay ee oh’ appears in the 1933 article for actress ‘Miss Whitney Bourne in the shadow of the Tyrol’.3

By then, followers of high fashion were familiar with millinery Tyrolean chic, but it did not appear in knitted form until later that year, created by Elsa Schiaparelli.

In collaboration with her powerful patroness and muse, American heiress Millicent Rogers, Schiaparelli started a fashion that still captivates us today. Photographed in November 1933 by Horst P. Horst, famed photographer with Vogue, Millicent Rogers (then Mme Artur Ramos, who was her third husband) wears a knitted Tyrolean style hat, which in true Schiaparelli style is embellished with a novelty woollen feather. That was it! A style was born.

It was the hat that everyone wanted to copy and make for themselves. The first to appear were patterns for crochet rather than knitting, most probably because of the better suited nature of a crocheted fabric, first released in America in early 1934 in quick response to the new trend.

Millicent Rogers, Schiaparelli’s muse

Millicent Rogers was a firm friend and patroness to Schiaparelli, and they often worked collaboratively to create many innovative designs that always took the fashion world by storm. She was a wealthy American heiress, revered as a leading fashion icon and Industrial Royalty with a highly individual style, always with the spotlight on her wherever she went. As soon as she embraced Tyrolean style – and her own distinct interpretation of it – it was endorsed the world over.4

Millicent had a close relationship with Austria and the Tirol, having eloped to Vienna in 1924 with her first husband, Austrian Count Ludwig von Salm-Hoogstraeten (though their marriage and residence in Austria were short-lived). She returned to St Anton in 1934 with her third husband Arturo Peralta-Ramos, where they built their own home, Villa Shulla, in the Arlberg mountains at the heart of the skiing elite.

Millicent Rogers in her customary Tyrolean dress at home in the Tirol in 1936.

A serious student of true traditional Tyrolean style, Millicent reportedly made sketches from the costume collections in the museum at Innsbruck, and had her designs made up by local tailors, closely based on original traditional costume ‘Trachten und Dirndl’. Local seamstresses made jackets, dresses, peasant blouses, quilted skirts and hats for her, all based on their expertise in traditional costume. Though it was unusual for society belles to dress in this way to say the least, she was committed to being authentic in her inspiration and to dress in harmony with her adopted surroundings. She wore these as her everyday dress when not in full ski clothes, and when her friend Diana Vreeland (writer for Harper’s Bazaar and later Editor in Chief of Vogue) visited in 1936, she noted a particular Tyrolean jacket of hers:

Millicent’s style was her own, but its lasting impact was made through her friends, advocates, and admirers in the fashion world.5

Never without the attention of the press in general and the fashion press in particular, her influential friends – Diana Vreeland and Louise Dahl from Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue – ran articles in 1939 on her Tyrolean lifestyle and commitment to maintaining traditional dress, following her return to America in 1938. Holding such sway in the world of haute couture, it was automatic for her style to become a main inspiration for the fashions of the day.

Even Wallis Simpson was inspired by her fellow American and followed her lead. For her wedding in June 1937 the Duchess of Windsor commissioned Millicent Rogers’ own favourite designers – Schiaparelli and Mainbocher – to create the trousseau for her honeymoon (taken in Austria, naturally) in the Tyrolean style. The Windsors had their own undeniable influence on fashion and played their part in drawing elite social circles to Austria.

The continuous English attraction to the Tyrol is delightfully related in the preface to a book of illustrations taken from eighteenth-century styles. Original Tyrolean Costumes6 was published in 1937, the year of the notorious Windsor wedding. This expresses Austria’s attributes ‘…the peasant dances and yodelling in which English people take so much delight…and that it has become almost a second home to so many English people.’ This brief but enlightening preface confirms that ‘Austrian peasant dress has in the last few years so markedly influenced styles in the international fashion world’ and prophetically ‘The Tyrolean vogue has achieved universal success; it is the fashion of to-morrow [sic] as well as to-day’.

Even more significantly from the point of view of Tyrolean-inspired fashions, we are encouraged to be inspired by the traditional dress: ‘If you want to make an interesting test of your personal taste, let these classic designs work on your imagination, then pick out something out of the ordinary and use it for a (design) of your own’. This welcome advice has been followed, using such details as inspiration in designing the Flowers for Laura cardigan in Chapter 5.

The 1937 book of Original Tyrolean Costumes charmingly illustrates traditional dress from the Tirol and neighbouring Austrian states, taken from historical sources. This page illustrates costumes of Kitzbühel from the Tiroler Volkskunstmuseum in Innsbruck.

Britain’s Response: The Stitchcraft Story

As to the rise in popularity of the Tyrolean style in Britain, we have an invaluable resource in the editorial reviews featured in Stitchcraft magazine, which was published each month by Patons and Baldwins from October 1932. Anne Talbot was their designated Paris correspondent with her finger on the pulse not only of fashion trends in general, but of knitwear in particular. Her monthly reviews are most informative, and sometimes surprising from our perspective, making many assumptions which history was indeed to prove were incorrect, but nonetheless are revealing of how the Tyrolean style came to make its mark in our knitting history.

Anne Talbot wrote for Stitchcraft from the first ever issue through to November 1937. We can make the most of what she tells us in that five-year time span, which turn out to be the pivotal years in the arrival and ever-growing popularity of knitwear in the Tyrolean style. She first makes mention in October 1933 of a knitted hat ‘…decidedly Tyrolean with a flat brim…and a stiff knitted “feather” up the side back of the crown’, which must be the same knitted Tyrolean hat by Schiaparelli that was causing such a stir in the fashion world in general. In November she mentions it again more specifically and credits Schiaparelli’s original design.

‘Schiaparelli’s newest little knitted hat, extremely reminiscent of that which the Tyrolese [sic] mountaineer wears.’ Stitchcraft, November 1933.

Anne Talbot would undoubtedly have had privileged insight into the emerging fashions from her vantage point in Paris. It was not until April 1936 that she began to include references in Stitchcraft to knitted jackets in the Tyrolean style, citing ‘The Tyrolean feeling has crept in bit by bit, starting with the hats of a year ago [even though she herself had mentioned them three years previously] and is a definite 1936 feature.’

Studying her reviews, it seems we can attribute the first examples of knitted jackets in the Tyrolean style to a fascinating designer who was new to the Paris scene in 1935: Kostio de War: ‘To Mlle De War, alone, goes the credit for all this chic originality…’

Lyska Kostio de Warkoffska was born in Baku, Azerbaijan in 1896. Also known as Lyska Kostio and from 1935 onward as Kostio de War, she was a French actress and fashion designer. In 1935, she founded the fashion house Kostio de War in Paris, specializing in high quality knitwear, which made her especially famous. She is credited with creating the first knitted plaid jacket, which also became an iconic piece of 1930s knitwear. During the war years she moved to Argentina, but her Paris fashion house remained open until 1953. In 2017, the Maison de War was reopened by her great-granddaughter, Sayana Gonzalez de War.

The design by Kostio de War which Anne Talbot describes shows every sign of being the first incarnation of what we now automatically think of as a Tyrolean cardigan, described in May 1936 as ‘a delightful little jumper of white knitted wool embroidered all over in a Tyrolean pattern of small wool flowers in gay colours’. Sadly any image of this has been lost in time but we have the description to fuel our retrospective imagination. Over the following months Anne Talbot gives us more tantalizing descriptions, as other designers pick up on the style, with occasional illustrations to whet our appetite further.

‘Early Autumn in Paris’ featuring a selection of illustrated Tyrolean-style cardigans (called ‘jumpers’) from Stitchcraft, September 1937.

The August 1936 issue of Stitchcraft features a two-page article with the title ‘Let’s go Tyrolean!’ (curious that so many similar titles for ‘Tyrolean’ felt the need for exclamation – there was evidently something inherently exciting about featuring this style). Even in this dedicated article there is a conspicuous absence of any knitted pattern in Stitchcraft, even though it acknowledges ‘the prevailing craze’ and encourages readers that ‘these inspirations from the Tyrol are good for other things besides clothes’.

In February 1937 Anne Talbot reports that ‘The Tyrolean influence in knitted wear has gradually waned in Paris, but has left a definite stamp in that its colourfulness is still evident. The gay Alpine flowers are gone, withered by the frost of Parisian satiety, but their vividness…lingers on.’ On and on, Ms Talbot, for almost ninety years and still going strong…

It seems curious that there are no Tyrolean patterns for knitted garments in the Stitchcraft magazines at this time when their own reporter was heralding the style (the only design which appeared in November 1937 has none of the characteristic colour work or embroidery). Nevertheless we owe Ms Talbot a debt of gratitude for her chronicles of the rise of the Tyrolean style in knitwear in the mid-1930s, month by month.

It isn’t until the later 1940s that we begin to see Tyrolean patterns featured in Stitchcraft magazine, when they then become de rigueur throughout the 1950s as front covers. Two of these patterns are included in the Pattern Collection (Chapter 4) as Knitted for Best from 1949 and Cosy for Cold Days from 1951.

‘We must have a Tyrolean Touch!’

Meanwhile, other contemporary British publications – Needlewoman and Good Needlework Magazine to name but two – were doing less talking about the style and more in the way of practical responses with actual patterns. There are superb examples which typify what we now think of as Tyrolean cardigans or jackets, with delightful variations to tempt knitters of all abilities. The earliest that research has so far revealed is from Needle-woman magazine of February 1937, with the superb example ‘The Needlewoman Cardigan’, which is offered as a full pattern, recreated in modern yarn, in the Pattern Collection (Chapter 4). Earlier patterns exist from 1936 as featured in American publications, notably Minerva’s superb collection ‘Minerva Styles the Future’. The Edelweiss Jacket from this is also included in the Pattern Collection as a fine example of colour work and embroidery.

‘Let’s go Tyrolean’ embroidery projects for ‘an amusing way to follow the prevailing craze’, Stitchcraft, August 1936.

‘We must have a Tyrolean Touch!’, featured in Good Needlework Magazine, April 1937.

Good Needlework Magazine for April 1937: ‘A Jumper Embroidered with the Gayest of Little flowers – Scarlet Daisies with Bright Green Leaves’.

‘June Clyde Sets a Fashion’

Probably the very first pattern bearing the name of Tyrolean was published in Britain as early as 1936, designed by Copley’s and endorsed by the charming American film star June Clyde, who was living and working in England at the time. First published in Picturegoer magazine, the story behind this pattern and its significance is given with the full instructions in the Pattern Collection in Chapter 4.

‘June Clyde Sets a Fashion’, featured in Picturegoer, Saturday 17 October 1936.

Popular Influence

Imagine the influence of the society beauties who adopted the Tyrolean style and their enviable lifestyles travelling to the elitist ski resorts of the Austrian Tirol, and add this to the rise of knitwear and the craft itself of knitting. Combined with the glamour of Hollywood and its celebrities endorsing the style, and the compelling coverage in the fashion press, the result is a formidable wave of powerful influence for a style which everyone wanted to share. Even popular songs about Tyrolean hats were the hits of 1937, recorded by no less than Gracie Fields and Billy Cotton and his Band (complete with yodelled introductions!) and promoted by the everpopular Henry Hall.

‘A Feather in her Tyrolean Hat’, by Annette Mills, song sheet from around 1937, recorded by Gracie Fields.

Suddenly, every publication which included knitting and patterns began to feature something Tyrolean, with engaging headlines to convince their readers that their pattern was the genuine article, and even making it imperative to make something in the style. It was a compelling message.

Star quality

1936 was certainly the pivotal year for the meteoric rise of the Tyrolean style and many film stars of the day followed the fashion and were captured on camera wearing fashionable outfits and notably knitted jackets. Marlene Dietrich herself wore hats and jackets alike, and was seen in Salzburg accompanied by her daughter and friend wearing classic 1930s Tyrolean-style cardigans. The following year, Claudette Colbert was featured on the front cover of Picturegoer on 17 July 1937 as part of a photo shoot where she wears a distinctive Tyrolean-style knitted cardigan.

The Influence from Austria

It is worth noting here the part played in spreading the style by Austrian companies, including Lanz and Geiger. In Salzburg in 1922 Josef Lanz founded what was to become an international empire around traditional Tyrolean designs, still going strong today. He maximized the momentum that popularized the recently launched Salzburg Festival, which was firmly placed as a highlight of the season for international high society. No doubt looking to escape the horrors of the Anschluss, the Nazi annexation of Austria, and on the strength of the popularity of his brand of traditionally inspired Tyrolean designs, Lanz emigrated to the States in the later 1930s. In 1936 he opened his first shop in Manhattan as purveyor of fine Tyrolean-style garments for the winter sports elite. In 1940 he set up in Los Angeles, enjoying a roaring trade feeding that insatiable appetite for all things Tyrolean which was still evolving in the 1940s and onwards.7

Lanz designed two knitted cardigans in Tyrolean style which were illustrated in the New York Times in July 1936, featured in an article by Fashion Editor Virginia Pope:

HIGH-STYLE KNITTING: Yarn and Needles Produce Latest Trends – Flower Patterns for Dress and Sports. All over the country needles continue to click, and justifiably so, for styles in knitting become better looking all the time. More distinguished designers are taking a hand in planning and working out beautiful garments for women who knit. Lanz of Salzburg is the author of the two sweaters shown [in the article], or rather their prototypes, for these were produced in this country. They are typical of the enchanting things worn in the Tyrol, with their snug collar bands and their attractive buttons. The patterns in typically gay peasant color schemes are embroidered after the knitting is completed.8

It may well be that these were the earliest designs for Tyrolean cardigans to be brought to the attention of America. Josef Lanz assuredly deserves credit as one of the first creators of the style, for after all he had extensive knowledge of the traditions on which to base his designs. No reference is given in the article to the Minerva pattern collection of the same year, ‘Minerva Styles the Future’, where both patterns appear, and similarly the patterns make no mention of their apparent designer. The Edelweiss Jacket is included in the Pattern Collection in Chapter 4 of this book, as one of the defining designs from the early days.

‘Minerva Styles the Future’, collection of patterns from 1936/7 with a focus on Tyrolean designs.

The darling of Lanz was fellow Austrian and beautiful Viennese-born film star Hedy Lamarr, who wore dresses created by him in Ziegfeld Girl (MGM, 1941), amongst other films, and who helped fuel the fire for Tyrolean fashion, as witnessed by the stellar list of customers who became Lanz followers as a result, including Marlene Dietrich. Knitted Tyrolean garments are still created by Lanz, and continue to be highly collectible, nearly 100 years on.

The Genuine Article: ‘Trachten und Dirndl’

But what was the genuine article…and were any of these new knitting patterns even close to the original Tyrolean costumes which they claim inspired them?

The traditional style of Tyrolean dress and all its glorious variety from community to community is known as ‘Trachten und Dirndl’: Tracht refers to national dress and Dirndl means a folk or rustic style (though the meaning evolved to mean young girls and their style of dress). This translated into English fashion as dirndl skirts, which are deeply gathered at the waist. Each region of the Tyrol has its own distinctive Trachten, which is proudly preserved by their community, headed by their own Heimatwerk or association, guarding its heritage and perpetuating traditional crafts and costumes. Tyrolean costume must be one of the rare examples of a traditional national dress which still has an eager market and is still in demand to be recreated in detail – the list of thriving makers and shops is impressive.

Comparing historical illustrations and old photographs, including 1930s contemporary costume, evidence that shows where the familiar formula for knitted Tyrolean jackets originated remains elusive. The key garment was the ‘Janker’ or Loden jacket, but very few original images show this or any type of winter attire for ladies, who are usually captured in summer clothing. In a climate which plummets with annual reliability to snowy sub-zero temperatures, this does seem perplexing. The Janker jackets are recorded as being made of boiled wool for insulation and hard-wearing, with the typical leg-of-mutton sleeves and tailored shape, and often embroidered, but crucially none of them is knitted.

The familiar embroidered flowers were featured on the corset-style bodices called ‘Lieberl’, but very few knitting patterns feature a bodice effect and this does not seem to have caught on in knitwear designs at the time. It is not a knitted style that has survived the decades in the same way as the fitted jacket or cardigan which has embroidered ‘panels’, but the 1940s pattern by Weldons captures this perfectly.

The Costume Museum of Innsbruck holds a collection of samples of knitting stitches, but an original version of what we consider a Tyrolean cardigan with added embroidery and coloured edgings remains undiscovered. It may not even matter how historically accurate the first designs were, but rather that we should just enjoy how the style evolved and how it has given us a glorious legacy of knitted treasures which still lives on today. It is rather like trying to identify the real King Arthur… Tyrolean style may use the name, some of the traditional stylistic details, and yet be far removed from the original costumes. Like Arthurian literature through the ages, what counts is that it has inspired such a wealth of wonderful creativity!

An original postcard of traditional Tyrolean dress, ‘Tiroler Trachten’, dated 4 November 1908.

Tyrolean buttoned-top pattern by Weldons 585.

A political undercurrent

Tyrolean-style knitwear was beginning its long and happy journey in the later 1930s, but this was a time when European politics was taking a very sinister direction, and the background of historical events cannot be overlooked. As the Nazis appropriated traditional costume ‘Trachten und Dirndl’ as a nationalistic emblem, it is even more surprising that any related style, such as the knitwear, was able to rise above this and not be rejected by association.

Hitler attempted to enforce ‘Trachten und Dirndl’ as the only acceptable mode of dress for women but not surprisingly this was ultimately unsuccessful. In his insightful chapter in Forties Fashion: From Siren Suits to the New Look9, Jonathan Walford explains in detail the way in which Naziism attempted to take hold of German fashions by prescribing the Dirndl as the ideal for German women.

Austria was subjected to enforced annexation in the Anschluss of 1938 when it lost its independence to Germany. Many Austrians fled while they still could, leaving for America or Britain to escape the terrors of the Nazi regime. Those who came to Britain did not always find the refuge they sought, believed to be German and being interned soon after as enemy aliens. Trudi Kanter, an established and talented Viennese hat designer, escaped to London in 1938 and the published diary of her experiences, Some Girls, Some Hats and Hitler10, is a most moving account of the perception of Austrians in Britain during the war years.

In spite of the fear and rejection of Austrian culture, the fashionable Tyrolean style which came from the same country was never subject to the same suspicious discrimination, and continued to thrive throughout the war years. It is heartening for all knitters that this was the case, and whether from blissful ignorance or conscious choice, it ensured the survival and continued celebration of the Tyrolean style in all its glory.

Tyrolean Style in the Twenty-first Century

The legacy of Tyrolean style continued right through the twentieth century and can be seen in fashions of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, especially in knitwear designs. Even in the 1960s when fashion styles made some highly questionable detours, there are a few knitting patterns related to the style, mostly in patchworks of primary colours, but nonetheless claiming their Tyrolean inspiration. The huge impact of the Rogers and Hammerstein film The Sound of Music in 1965 should not be forgotten. Set in Salzburg, the Tirol’s neighbouring state, the iconography is generally perceived, rightly or wrongly, as Tyrolean in style. A new revival of the ‘Peasant Look’ in the late 1960s and early 1970s, reminiscent of the 1930s trend, also drew on Tyrolean patterns for fashionable styles.

The 1980s saw a huge revival of hand knitting and Tyrolean patterns were reliably found in collections by all leading designers throughout the decade, such as the splendid colour work ‘Tyrolean Cardigan’ by leading designer Edina Ronay in her collection of 198811 and the wonderfully textured ‘Tyrolean Jacket’ by Debbie Bliss in the Country Knits collection of 199012, both still so relevant and wearable today.

The links in the Tyrolean style chain continued unbroken at the turn of the century, and under the revered banner of Rowan Yarns many of their leading designers brought out a new generation of Tyrolean-style knitwear. With the excessive volume favoured in the 1990s now tamed, designs of the first decade of the twenty-first century relate even more closely to the styles of the 1930s and 1940s, following a huge wave of revival for vintage styles in knitwear. Leading knitwear designers featured beautiful patterns in Rowan publications. Vintage Style13 includes the ‘Tyrolean’ pattern by Sarah Dallas; an intricately bobbled and embroidered cardigan, also featured on the cover of this 2004 collection. Martin Storey’s Alpine collection of designs for Rowan Classic in 200814 includes a number of superb patterns directly inspired by Tyrolean knitwear, such as the chunky wool jacket ‘Tyrol’. Contemporary knitting magazines also continue to feature new patterns on the theme of Tyrolean knitwear, such is the everlasting enjoyment and interest.

Tyrolean style in haute couture

Far from losing its appeal after so many years, Tyrolean style has continued to inspire fashion designers of knitwear and haute couture clothing into the twenty-first century. The very height of international fashion focused on Tyrolean and Alpine style once again in 2014–15, seen most notably in the new season’s collections by Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel15 and Riccardo Tisci for Givenchy16,17. Tyrolean style continues to inspire, from haute couture to the high street.

As recently as Autumn 2019, high street fashion leaders ran collections of knitwear entirely Tyrolean in style, attracting huge popularity with hand-embroidered flowers adorning vintage-inspired shapes and great attention to detail.

The universal passion for Tyrolean style is as alive today as it was ninety years ago, and will continue to be celebrated for many more generations to come.

Cotton Tyrolean-style cardigan by Zara, Autumn/Winter Collection 2020.

The Pattern Collection in This Book

The collection of vintage Tyrolean knitting patterns in Chapter 4 has been carefully chosen from the ones that stand out, not just as statements of the style, but also as opportunities for the knitter to recreate vintage treasures from a pattern that works. This does not include every single pattern that might qualify for the title as there are many (and not all of them would be worthy!), but it endeavours to be a refined collection of key designs focusing on the golden era of the 1930s, 1940s and early 1950s.

Some of the more familiar patterns have been omitted in order to make way for some rarer discoveries. There will be some presented here for the very first time to modern knitters, with original patterns offered alongside adapted versions. Techniques, colours, materials and finishing touches are explained to achieve an authentic vintage garment, along with new interpretations capturing that unmistakable vintage Tyrolean style.

The Tyrolean hat button symbol at the beginning of each pattern indicates the level of skill required to knit the garment. Patterns are graded from one to four buttons.

CHAPTER 2

MASTERING VINTAGE YARNS AND PATTERNS

A Practical Guide to Vintage Yarns

For the lover of vintage knitwear eager to knit from an original pattern, one of the first challenges is to know which wool to use to create the closest match. New and experienced knitters alike often take a chance when buying a modern yarn to use with vintage pattern instructions. There is much generalized recommendation for substituting yarn weights, but this chapter gives exact comparisons using actual vintage yarns as the starting point, comparing like-for-like with modern yarns and their own variations.

A vintage 3 ply or 4 ply is not the same as a modern yarn of the same name. Vintage yarns in these weights are slightly thicker than their modern name-sakes, which can be misleading ‘faux amis’. The following guidance will help to decode vintage yarn weights and how to substitute these successfully with modern counterparts.

A note on tension

Modern yarn very helpfully includes an expected average tension on the ball band, but this does not appear anywhere on vintage yarn labels. Individual vintage patterns designate a yarn type, usually by brand, and sometimes by delightfully poetic names – Glengarry, Cryscelle, Totem – which do not give any clue as to ply or weight. The only indicator is to check the suggested tension given in the pattern, and match this to a modern yarn with a compatible tension. Note that vintage patterns usually give their tension as the number of stitches per 1” or sometimes 2” (2.5 cm and 5 cm respectively), where modern yarn states tension per 4”/10 cm.

If the pattern states a completely different size needle from that given for the modern yarn, go with the modern needle size recommended for your chosen yarn to achieve the same tension as in the pattern (but always adapting the needle size as necessary to accommodate your own tension results). The size of needles used is not the governing factor in this situation: what you are aiming for is a stitch count that is equivalent to that in the pattern.

The secret is always, always in the tension. Seen by many as an irritating side step and delay to starting a new exciting project, it is of crucial importance. It is the surest way of matching your work to the intended size of a vintage pattern with a modern yarn equivalent. The advantage of doing this is that once you have verified your own individual tension with a particular yarn and needle size, you will not need to run it again, and can assess other vintage patterns accordingly. It will also help to find the modern yarn that works best for you. Keep a note of your tension for future reference, knowing how to adapt this to the vintage patterns you will be knitting.

Some vintage patterns do not give a tension at all, or only give a tension size based on a complete repeat of the specific stitch pattern, which is of no immediate help in ascertaining which modern wool to substitute. There are still clues! The number of stitches cast with the recommended needle size suggests which weight or ply has been used (even if there are anomalies such as 2 ply knitted with 3.75 mm/9 needles, which is not unusual in the 1940s in particular, when less wool needed to go so much further). The direct comparisons of yarn given here offer a general guide to help with matching equivalents.

Vintage Patons Beehive ‘white’ wool in original packaging.

Vintage 3 ply

The majority of patterns from the 1940s use 3 ply yarn, a fine yarn which produced around 30–32 sts. to 10 cm/4” tension knitted on size 3.25 mm needles. Many patterns also knitted with this on size 3.75 mm needles (old imperial size 9) in order to make more with the wool available. It is thicker than modern 3 ply, which is generally used today for babies’ knitwear, and using modern 3 ply in its place will give results which are too small for knitters with an average tension, unless the needle gauge is adjusted accordingly to a larger size, which in turn will create a very open stitch and loose fabric.

Vintage 3 ply is not as thick as most of our modern 4 ply yarn, but this is the closest match available and there are some which come very close in fineness and the resulting fabric they achieve. Modern 4 ply has the added advantage of giving very slightly bigger results, which are often welcome in comparison with the small measurements that so many vintage patterns work to.

3 ply was usually sold in skeins or balls of 1 oz, equivalent to 28 g, and as a rule, you will need as many balls of 50 g in modern 4 ply as are given in the materials specifying 3 ply – surprisingly this is almost double the weight specified in a vintage pattern, but taking into account the slightly finer ply, and longer length as a consequence within the ball or skein, it seems to work out with fairly fail-safe results.

Modern labels also usually state the length of the ball of wool, but vintage labels do not, so this is not a readily useful measure of comparison.

Vintage 3 ply yarn with original labelling.

Matching modern 4 ply to vintage 3 ply

Modern 4 ply has an average tension of 28 sts. to 10 cm/4” knitted with 3.25 mm/10 needles. However, the real results can vary widely according to different brands. Shown here are a few of the popular brands and how they compare to original vintage 3 ply. This is not exhaustive, but gives a range of examples and their different results.

In order to compare yarns as closely as possible, each of the samples of 3 and 4 ply given here has been knitted in the same way: 30 rows knitted on 30 stitches using 3.25 mm/10 needles. The standard recommended tension for modern 4 ply is for 28 sts. to 10 cm/4”.

Vintage 4 ply

Thicker than our modern 4 ply, this yarn weight is not as thick as our modern Double Knitting (DK). There are some lighter weight DK yarns available today which come closer, and some of our 4 ply yarns that knit up more densely are also a good substitute. The tension given in the pattern will be your guide as to which type of yarn to choose. Some vintage patterns that specify 4 ply (of the vintage variety) use 10/3.25 mm needles, which if used with most of our DK yarns would result in a very dense, stiff fabric. If smaller sizes of needles like these are specified in the pattern, this would indicate that a finer yarn would work better than a DK.

If the pattern’s tension states 6 sts. to 1” (equivalent to 24 sts. to 10 cm) then a DK would work well, using the needle size recommended on the modern ball band to achieve this tension, or adjusted to your own tension, irrespective of the needle size stipulated in the pattern. As with 3 ply substitutes above, the key is to match the stitch count to that of the pattern with the appropriate size of needles and a compatible yarn type.

One of the Patons annual Woolcraft booklets with the original 3 ply yarn illustrated on the cover.

Original vintage 3 ply (centre) achieves an average tension of 30–32 sts. to 10 cm/4” knitted on 3.25 mm/10 needles. These like-for-like samples are each of 30 sts. and 30 rows and the four knitted in modern 4 ply yarns show which offer closest matches: Cygnet, Cascade 220, West Yorkshire Spinners and King Cole Merino.

Original vintage 4 ply (centre top) achieves an average tension of 26 sts. to 10 cm/4” and is thicker than modern 4 ply, but finer than modern double knitting, which has an average tension of 22 sts. to 10 cm/4” on 4 mm/8 needles. These like-for-like samples of modern DK are each of 30 sts. and 30 rows, showing the additional width this achieves.

Vintage Patons Purple Heather 4 ply.

As before, in order to compare yarns as closely as possible, each of the following samples of vintage 4 ply and modern Double Knitting (DK) given here has been knitted in the same way: 30 rows knitted on 30 stitches using 4 mm/8 needles. The recommended average tension for DK is 22 sts. to 10 cm/4” on 4 mm/8 needles.

Sizing up

Most vintage patterns work to a size 34” bust – often as a given, without even specifying this – and an easy way to size up to a 36” bust is to use a modern 4 ply with no alterations to the pattern or numbers of stitches. Use this with larger needles – 3.75 mm/9 – and it will work out to a size 38–40” bust. Similarly, if you are working with modern 4 ply and want to keep the size to a 34” or less, use smaller needles – 3 mm/11 – to achieve this. It can be that easy! In all cases, check your tension before starting, to make sure your work will achieve the size required.

Vintage ‘Double Knitting’ or Quick Knit

After the war, towards the end of the 1940s, thicker yarns were produced again that are comparable to modern DK but, again, slightly thicker than our modern yarn. The names given to these appealed to the desire for speedier knitting, and were variations on the theme of ‘Quick Knitting’, ‘Speediknit’, and even ‘Kwiknit’. These were often closer to our modern (UK) Worsted weight, which is between DK and Aran (usually worked at a tension of 20 sts./10 cm on 4.5 mm needles). This new weight of post-war wool is easier to match today, as we have such a wide range of DK and thicker yarns available in varied fibres.

The first Quick Knit yarns would still have been in pure wool until the early 1950s, when nylon started to be added. Many modern-day yarns include some synthetic fibres, most often acrylic, but our modern pure wools have a great advantage over their vintage relatives by being fully washable. Modern synthetics are welcome not only for their ease of care, but also for avoiding allergic reactions, even with wool content. Some modern brands of pure wool are specifically marketed as ‘anti tickle’, usually using Merino wool which is softer.

Vintage Patons Double Quick yarn.

Comparison sample of vintage Patons Double Quick yarn with Sirdar Country Classic Worsted (used in June Clyde’s Jacket in Chapter 4), which is thicker than modern DK and closer to vintage ‘Double Knit’.

Thicker vintage yarns

These were very popular in the 1930s, before the war impacted wool supply. They are rarely given a name or ply (like our Aran, Chunky etc., which are more modern terms) and are identified by the tension, size of needles and number of stitches specified in the pattern. These were very rarely used in patterns during the 1940s, and only started slowly to reappear after wool rationing ended in 1949.

Vintage 2 ply

Popular from the 1930s into the 1940s, and even more so in the post-war years when coupon saving continued to be a necessity, this very fine yarn was less commonly used from the 1960s onwards. Even if knitted with larger needles (which gives a very open fabric), it requires much work to produce a whole garment. It has had a resurgence in the last ten to fifteen years as Lace Weight, mostly for delicate pieces such as lace shawls. Our modern 2 ply is once again much finer than its vintage counterpart, and does not achieve the same finished size unless adjustments are made to compensate for the finer stitches.

As none of the Tyrolean patterns sourced are worked in 2 ply yarn, and this is not applicable for the Pattern Collection in this book, this weight of yarn is not compared here for modern substitution. Only Shetland 2 ply has retained its original application, favoured for traditional Fair Isle knitting, and indeed is compatible with modern 4 ply yarn.

Buying Vintage Yarn

There is something infinitely satisfying about knitting from a vintage pattern in original vintage yarn, especially if you have the good fortune to chance upon the very yarn specified in the pattern. It is hard to find, but there is still some out there and it surfaces in often unexpected places.

The greatest enemy of vintage yarn is moth, the dreaded tiny destruction machine. To be precise, it is moth larvae that are the culprits, devouring their way through any yarn once they have hatched, and the softer it is the more appetizing to them! Before buying vintage yarn, check if it has been invaded by moth – this is more difficult to see in balls and easier in loose skeins. The tell-tale signs are breaks in the wool which look like frays, or holes in the paper of the ball-bands. Breaks do not necessarily go all the way through the ball or skein but if they have, then it is a hopeless case. You could end up with a bundle of very short sections, sometimes too short to use, even if knotted together in any practical way. These are more useful for embroidery or colour work, if you are lucky, but unusable for larger main pieces.

Even if you cannot see any evidence of moths having gorged themselves, it is advisable to put the yarn in a plastic bag and consign to the freezer for a minimum of three days, ideally ten days or more. This puts paid to any eggs hatching and doing further damage. Alternatively – and even additionally – washing is the best remedy for dormant moth larvae. If you have acquired vintage wool skeins, it is easy to wash these before you start your work, and this also helps to address any potential shrinkage or colour running prior to making. If the wool is in balls, you can wash the garment once completed.

Caring for Vintage Yarns

Washing vintage skeins

To freshen skeins of vintage wool that will have been stored for many years, a gentle wash will revive them and have the added bonus of eradicating any traces of dreaded moth. Before washing, untwist the skein without cutting or unwinding the yarn. It will naturally fall into a large loop which will have the ends tied together. It is a good idea to tie additional scraps of wool around the yarn in two or three places along the skein to hold it together and avoid any tangling during washing.