20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

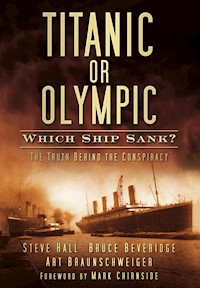

The Titanic is one of the most famous maritime disasters of all time, but did the Titanic really sink on the morning of 15 April 1912? Titanic's older sister, the nearly identical Olympic, was involved in a serious accident in September 1911 – an accident that may have made her a liability to her owners the White Star Line. Since 1912 rumours of a conspiracy to switch the two sisters in an elaborate insurance scam has always loomed behind the tragic story of the Titanic. Could the White Star Line have really switched the Olympic with her near identical sister in a ruse to intentionally sink their mortally damaged flagship in April 1912, in order to cash in on the insurance policy? Laying bare the famous conspiracy theory, world-respected Titanic researchers investigate claims that the sister ships were switched in an insurance scam and provide definitive proof for whether it could - or could not - have happened.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Mark Chirnside

Preface

Introduction

1 Ismay’s Titans

2 Olympic and Titanic

3 Seeds of the Conspiracy

4 Mystery or History?

5 The Lifeboat Evidence

6 A Window of Opportunity

7 Photographic Assessment

8 The Final Verdict

Conclusion

Appendix I Almost Identical Sisters

Appendix II Olympic: The Last Grand Lady

Appendix III His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Britannic

Endnotes

Select Bibliography

Plate Section

The Authors

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Unless otherwise credited, all images are from the authors’ collections.

Scott Andrews, for sharing his considerable knowledge of period shipbuilding practices and providing the information on Olympic and Titanic’s propulsion machinery.

Mark Chirnside, for taking the time to review the text on Olympic and Britannic.

Roy Mengot, for providing access to the analyses done by the Marine Forensics Panel of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers.

Ray Lepien and Robert Compton, who contributed so much to the original manuscript.

George Behe, for sharing his substantial knowledge of Titanic’s passengers and crew.

Daniel Klistorner, who supplied some rarely seen images of Titanic.

Jonathan Smith, for providing rare photographs and postcards from his collection.

Cyril Codus, for his Titanic and Olympic drawings.

Tom Cunliffe, for checking the navigational information cited for the waters in and around the Solent.

Charles C. Milner, for allowing us to use several of his period postcards.

Samuel Halpern, for providing additional information on Titanic’s lifeboats and the White Star Line.

John White, with special thanks for allowing us to use photographs taken of his extensive White Star Memories collection of Olympic artefacts. Photographs by Liza Campion (copyright White Star Memories).

R. Terrell Wright, for allowing the use of his rare photographs.

Josha Inglis and Stewart Kelly, for their interior woodwork photos.

Bernhard Funk, for his dive footage.

Mark Darrah, for his support and the use of his Engineering and The Engineer photos from the Harland & Wolff archives.

Alastair Arnott of the Southampton City Archives, who also assisted with photographs.

Charles Haas and Jack Eaton, for the use of photographic material from their book Titanic: A Journey Through Time.

The Titanic Historical Society, Indian Orchard, Massachusetts.

Frank and Dennis Finch and Kyogle Maritime Museum.

R.J. Thomson, Manager, Marine Crews at the Australian Maritime Authority (1997).

Bob Read, Steve Rigby, the British Titanic Society, Ralph White, Peter Quinn, Remco Hillen, the folks at the Bridgeview Public Library and any other contributors we may have missed.

Karen Signell Andrews, for editing the original 2004 version of this text.

The staff of The History Press, and in particular, Amy Rigg and Emily Locke, who have worked closely with us on our many Titanic projects, and who have somehow always managed to remain calm during our many requests for deadline extensions.

And Robin Gardner, for giving us something to write about.

FOREWORD

‘From the assassination of JFK in November 1963, through Watergate and Lockerbie, conspiracies beset popular culture.’ So writes Jane Parish in The Age of Anxiety: Conspiracy Theory and the Human Sciences. ‘Television programmes about mysteries and “inexplicable” events command peak-time viewing schedules, reinterpreting “old” conspiracy theories with new evidence. Sky television devotes a single channel to programmes about mysterious happenings. In the tabloid papers, conspiracies have caught the public imagination… Reflecting this trend, the best-selling books of the 90s reflect a widespread fascination with conspiracy, intrigue and secret organisations…’

Perhaps it is unsurprising that one of the most famous maritime disasters in history, Titanic’s sinking, became the subject of an extraordinary conspiracy theory: that Titanic did not sink at all. According to the theory, the ship that sank on 15 April 1912 was actually her near-identical sister ship Olympic, which sustained damage during a collision with HMS Hawke on 20 September 1911. Theorists believe that the damage was so serious that Olympic was an economic write-off, and so she was switched with her sister. The plan was to deliberately scuttle Olympic, but she struck an iceberg accidentally and began to sink far more quickly than was originally anticipated.

The theory is far-fetched, and yet – is it possible? Conspiracies suggest deception and intrigue, and none is quite as intriguing as the idea that the White Star Line pulled off such a massive cover-up. However, dismissing such a claim out of hand is not enough. It requires rigorous analysis by researchers who have the relevant expertise and objectivity to assess it. It demands examination of the all the claims put forward point by point, by looking at the evidence and seeing whether it supports them. Moreover, it demands that the evidence be presented in such a way that the non-technical layperson can assess it for himself

If such a theory is absurd, then why is it necessary to examine it in such detail? Might not a conspiracy theorist simply dismiss such a critical analysis in any case? Perhaps so, but a detailed analysis also provides a service to the intelligent layman by pointing to the specific problems with the theory. There is much to be said for ignoring it – few would debate seriously with the argument that the earth is flat – but any theory should be assessed objectively by examining whether there is any evidential basis for it. While this volume looks for flaws in the conspiracy theory, it also provides a lot of historical information. It documents the hundreds of differences between Olympic and Titanic, all of which must be considered in answering the question ‘could it have really happened?’

When someone puts forward an idea or theory, then it is incumbent on them to prove it. There will always be people who believe what they want to believe, rather than what can be demonstrated to have happened, but that is their choice. Herein lie the facts – decide for yourself.

Mark Chirnside

October 2011

PREFACE

‘Titanic is unsinkable.’ This phrase strikes a chord in the mind of any Titanic enthusiast and is reiterated in nearly every Titanic book printed. These same words are frequently cited as proof of shipbuilder and ship owner’s arrogant overconfidence in what they had created, and yet no one ever uttered them. They are quoted inaccurately from a period trade publication The Shipbuilder, which described Titanic and Olympic as ‘practically unsinkable’.

Inaccurate stories are not new. Immediately after the sinking, there were even reports of Capt. Smith being seen on the streets of New York City. Some researchers, however, have used elements from the information available on Titanic to form ‘conspiracy theories’. Many are far-fetched, completely ridiculous, or both. The Jesuit conspiracy theory is one: there are many variations of this story, all of which are based on the belief that the Jesuits have been controlling world events behind the scenes for hundreds of years.

In the early 1900s in the United States, there was no national banking system – what is known today as the Federal Reserve System. As the Jesuit conspiracy theory claims, in 1910 a clandestine meeting supposedly occurred on J.P. Morgan’s Jekyll Island off the coast of Georgia, attended by Nelson Aldrich and Frank Vanderlip of the Rockefeller financial empire; Henry Davidson, Charles Norton and Benjamin Strong representing J.P. Morgan (a member of the Jesuit order); and Paul Warburg of the Rothschild banking dynasty of Europe, reportedly the banking agent for the Jesuits. Their common interest was the centralisation of America’s financial resources and elimination of outside competition in the banking world. This would ultimately ensure that more wealth flowed to the Roman Catholic Church and would also ensure that the United States had the financial means to fund a world war, favoured by the Jesuits in pursuit of their aims.

However (according to conspiracy theorists), the concept of a Federal Reserve was opposed by three of the most wealthy and influential men in the country: Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor Straus and John Jacob Astor. Their opposition had to be eliminated in order for the Jesuits to succeed. Plans were made in which J.P. Morgan would arrange for the three to take passage aboard Titanic, which was then being built, for a pre-arranged fatal maiden voyage.

The theory claims that Titanic’s captain, Edward John Smith, was a ‘Jesuit temporal coadjutor’: not a priest, but a Jesuit who served the order through his profession. Through him, an accidental sinking could be arranged. A Jesuit master – a passenger from the order named Frank Browne – would board the liner for the short trip between Southampton and Cherbourg. Browne would order Smith to run his ship at full speed through an ice field on a moonless night, ignoring any ice warnings, including those from the lookouts, with the purpose of hitting an iceberg severely enough to cause the ship to founder and cause Guggenheim, Astor and Strauss to drown. In other words, the ship and her crew and passengers were to be sacrificed to eliminate three men. As their evidence, these theorists point out that after the sinking, all opposition to the Federal Reserve disappeared. In December of 1913 it was established in the United States, and eight months later (according to the conspiracy theorists) the Jesuits had sufficient funding to launch a European war. This particular theory, however, has never addressed why the conspirators in 1910 would feel that sinking a ship was a practical way to eliminate enemies of the Jesuits, to say nothing of how they would arrange for all three victims to board a specific ship on a specific voyage two years later. This is but one conspiracy theory involving Titanic; this book deals with another quite different.

Until 1985, the wreck of Titanic was a much sought-after prize that many considered equal to the quest for the Holy Grail. Over fifty books had been published covering the disaster from every conceivable angle. In the years following the discovery of the wreck, an estimated 120 new books were written, generally retelling the same old story, albeit with a wealth of new technical data and photographs acquired during the numerous return expeditions to the wreck site. Added to this has been an exponential increase in research on Titanic’s construction as well as forensic analysis of surviving photographs and the technical information they yield. While answering many long-standing questions, new questions have been raised that were never considered prior to her discovery and which have not been fully answered. Uncertainty spawns conjecture, and thus are born conspiracy theories. Some defy credibility, yet we cannot help but think ‘what if …?’

Complicating the picture is the fact that many of the original builders’ plans have disappeared over time, and many last-minute changes were made during construction that were never redrawn on the plans. Photographs are incomplete. Recollections of the surviving passengers and crew following the sinking are maddening in their contradictions. As an example, the testimony of nearly a dozen different officers and crewmen never established exactly what engine orders were rung down from Titanic’s bridge following the collision. Most of the testimony gained in formal hearings took place well after the event. With the passage of days and weeks memories fade and become corrupted by hearing what others remembered. Over the course of time, theory and fact have a way of becoming intertwined. Evidence can also be interpreted selectively to suit one’s convenience: holding some up as proof of a claim, while conveniently ignoring that which contradicts it. Then there are the technical aspects. Frequently one theory or another fails simply because those promoting it lack technical knowledge of period shipbuilding, maritime practices or other aspects and what is claimed simply could not have happened that way.

This book, originally titled Olympic and Titanic – The Truth Behind the Conspiracy, was first published in 2002. It is not a book that promotes a conspiracy theory. It presents a wealth of photographic evidence and examines, with objectivity and analysis, the claims supporting one particular theory. It is the intent of this book to examine that theory in light of some of the mysteries surrounding Titanic and her nearly identical sister, Olympic. In doing so, it also catalogues and compares the differences between the two ships, which were far more numerous than a casual glance would suggest.

The ship that today lies more than 12,000ft below the waters of the icy North Atlantic is nothing more than a rapidly collapsing and disintegrating hulk. Is it really Titanic?

Titanic leaving the dock at Southampton at the start of her first and last voyage. (R. Terrell-Wright Collection)

INTRODUCTION

On 20 September 1911, nearly seven months before Titanic entered service, an event took place on what started out as a routine beginning of an eastbound crossing for Olympic. A sudden collision between Olympic and a Royal Navy cruiser, the RMS Hawke, left Olympic with major damage and the prospect of expensive and time-consuming repairs. She was withdrawn from service, and the damage was found to be even more serious than originally feared. Thus was born the ‘switch theory’. Simply put, it holds that the wreck lying over 12,000ft below the surface is not Titanic but her sister ship Olympic and that the severe, crippling damage that Olympic suffered in the collision with RMS Hawke was concealed because she was too costly to repair. The cost of the repairs was not covered by insurance, nor would she recover the revenue lost while out of service. Therefore, the theory claims, Olympic was switched with her younger sister Titanic and deliberately sunk as Titanic, for whose loss insurance claims would be paid.

Support for this theory is partially based on the following points:

* Photographs taken of Titanic on 2 April in Belfast and on 10 April in Southampton show hull plates that appeared to be as faded and discoloured as those of a ship that had been at sea for over twelve months – not those of a ship that had been recently painted.

* There were remnants of white paint found on the hull of the wreck – a colour painted only on Olympic, never on her younger sister, Titanic.

* The fact that Titanic, the world’s newest and largest ship, was never opened for public inspection while she was at Southampton as was customary. (The theory holds that such public inspection may have revealed that the ship was, in actuality, Olympic.)

* During the American investigation into the loss of the ship, Senator William Smith persistently tried to establish whether the ship’s lifeboats were new since almost none of the lifeboats had lanterns as required by the Board of Trade and some started leaking once lowered into the water. (The lifeboats of Olympic, being older, were in theory susceptible to leakage, unlike new boats as would have been installed on Titanic.)

* Supposedly there was a conversation years later in which a person claiming to be a surviving Titanic crewman stated that when he joined the ship at Belfast, he heard rumours that the two ships had been switched and that the true reason for the sinking of the ship had been covered up.

Would it have been possible to successfully switch the two ships?

There was one opportunity – if it succeeded, it would be the greatest sleight of hand of all time.

1

ISMAY’S TITANS

The Olympic-class liners – Olympic and Titanic, and later Britannic – represented a 50 per cent increase in size over the Cunard vessels Lusitania and Mauretania, which were the largest and fastest liners in the world at that time. Although the Olympic-class liners would not be as fast as the two Cunard greyhounds, White Star Line policy was to emphasise the luxury of its ships’ passenger accommodations rather than speed.

To facilitate the construction of these three colossal vessels, Belfast shipbuilder Harland & Wolff would be required to make major modifications to its facilities. Two new slips were constructed in an area previously occupied by three. The William Arrol Company Ltd was contracted to construct two huge new gantries over these slips to carry the travelling cranes that would service them. When completed, the gantries covered an area 840ft long by 270ft wide.

Although the Olympic-class ships were originally conceived by J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, and Lord William Pirrie, managing director of Harland & Wolff, their actual planning and design was carried out by the shipyard’s principal naval architect Alexander Carlisle. Thomas Andrews was head of the yard’s design department and oversaw the creation of the plans of the class prototype (Olympic) but Carlisle took charge of the details until he resigned in 1911. Throughout all stages of design and planning, all drawings and specifications were submitted to Ismay for his approval. Any modifications or suggestions he believed necessary were, without a doubt, carried out.

Of the three ships, Olympic and Titanic were built first, side by side in the two new slips, whereas Britannic would not begin building until three years later. When completed, Olympic and Titanic registered at just over 46,000 gross tons each and measured 882ft 9in long and 92ft 6in wide at their maximum breadth. As a comparison to later ships, the German Imperator of 1913 was 909ft long and the Queen Mary of 1936 was just over 1,000ft. In an age of industry and accomplishment, these new ships would be true leviathans and would secure for the White Star Line a pre-eminent position in the North Atlantic steamship trade for years to come. Having a trio of the same class would also permit the White Star Line to guarantee a weekly service in each direction.

A photograph of the massive Arrol gantry taken on 27 March 1909, the day Olympic’s keel was laid. (White Star Photo Library/Daniel Klistorner Collection)

The Olympic-class ships were driven by a triple-screw arrangement powered by three engines of two different types. The port and starboard wing propellers were driven by two giant reciprocating engines, a form of motive power that was well established and highly reliable. These engines worked in much the same fashion as an automobile engine – with giant pistons and crankshafts – save that steam pressure was used to move the pistons within the cylinders. These engines were of the four-cylinder, triple-expansion type with a high-pressure, an intermediate-pressure, and two low-pressure cylinder bores of 54in, 84in, and 97in diameter respectively; each one had a 75in stroke. They were designated ‘triple expansion’ because the high-pressure steam from the boilers was fed first into a high-pressure cylinder, then, after it had expanded and moved the piston in that cylinder, it was exhausted into an intermediate-pressure cylinder to expand further and move that piston, and thence into two low-pressure cylinders to expand further and move those pistons. It was an economical means of propulsion in that the steam was made to do its work three times, although this type of engine did not yield speeds as high as a newer type of engine: the marine steam turbine.

The turbine engine – the motive power used aboard the Lusitania and Mauretania – functioned by directing steam past a series of vanes, closely grouped and fitted around a shaft directly attached to the propeller. In the same way that a windmill functions, the high-pressure steam expanding and passing through the turbine forced the vanes to spin the shaft. Higher speeds were possible than could be attained with reciprocating engines, albeit at the cost of more coal. As the White Star Line’s goal was luxury and not speed, this design was not favoured as the principal means of propulsion for the Olympic-class ships. However, the turbine could be used in another way. By incorporating a low-pressure turbine engine in addition to the other two, use could be made of the latent energy that still remained in the steam even after it had been exhausted at sub-atmospheric pressure from the low-pressure cylinders of the reciprocating engines and before it was condensed to water and returned to the boilers. This low-pressure turbine drove the central propeller shaft, although it could only operate at higher speeds. After trials on various ships, the combination of two reciprocating engines and a single low-pressure turbine engine was found to be the most economical in terms of coal consumption and yielded a service speed that was eminently satisfactory. Each of the reciprocating engines developed 15,000IHP (indicated horsepower) at 75RPM (revolutions per minute). The low-pressure turbine developed around 16,000SHP (shaft horsepower) at 165RPM. Combined, the three engines within each of the Olympic-class ships could generate up to 51,000HP (and just over 59,000 if forced), giving the ships a service speed of 21 to 21½ knots with up to 24 knots possible when required.

The steam required to power the three massive engines on each ship was provided by twenty-nine huge boilers arranged side by side in six boiler rooms. Each had multiple furnaces within which the coal burned to heat the feedwater into steam. The five boilers in the aftermost boiler room were single-ended, with furnaces at one end only. The remaining twenty-four were double-ended, and were twice as long, with furnaces at each end. With three furnaces in the five single-ended boilers and six in the double-ended ones (three furnaces at each end), this required up to 159 furnaces to be kept burning with coal simultaneously. All had to be fired in a never-ending rotating sequence, and every piece of coal had to be shovelled by hand. This required a ‘black gang’ of 175 firemen, plus more than seventy-five trimmers whose job was to move the coal from the bunkers to the boilers. With the ship running at its normal service speed of 21 to 22 knots the furnaces could consume 620 to 640 tons of coal per day. The ship’s coal bunkers, situated between the boiler rooms, had a combined capacity of 6,611 tons and an additional 1,092 tons of coal could be carried in the reserve bunker hold just ahead of the forward-most boiler room.

This image taken on 2 July 1909 shows Olympic’s partially plated Tank Top and wing tanks. In the slip to the left, Titanic is being constructed.

Steam from the boilers not only powered the engines that drove each ship, it also generated electricity. Four powerful 400kW dynamos, or generators, were driven by steam and provided electricity for the ship’s lighting, supplemental heating, much of the galley equipment, telephones, Marconi wireless equipment and myriad other needs. There were literally hundreds of miles of electrical cable throughout these massive ships; the lighting alone was provided by way of approximately 10,000 incandescent lamps. The four main dynamos were positioned in two side-by-side pairs within the Electric Engine Room aft of the Reciprocating and Turbine Engine Rooms, just forward of where the propeller shafts exited the hull. Two smaller 30kW emergency dynamos were located five decks higher up in the ship, and could function to provide emergency lighting in the event of catastrophic flooding around the propeller shafts putting the main dynamos out of service. A completely independent emergency lighting circuit could provide limited illumination in the event that the main lighting circuit was out of commission.

A ship of any size requires strength, stability and structure. The principal longitudinal strength centres on the keel, which in each Olympic-class vessel was a massive built-up construction of steel plating 1½in thick amidships and just under 1¼in thick at the bow and stern. Resembling a beam lying on its narrow edge, this vertical keel was 53in wide and 63in high, increasing in height to 75in in the Reciprocating Engine Room to provide additional strength to carry the massive reciprocating engines.

Hydraulic riveter at work on the vertical keel of Olympic. (Engineering/Authors’ Collection)

Four smaller longitudinal members running parallel to the keel on either side provided additional strength in a fore-and-aft direction, and vertical steel plates running in a cross-ways direction between them completed the bottom. From the outer curve of the bottom extending outward and upward were the ship’s frames, resembling a series of parallel ribs. These were constructed of 10in steel channels and were spaced 36in apart amidships, with the spacing gradually reduced to 27in at the stern and 24in at the bow where greater strength was needed to withstand the pounding of heavy seas as well as any light ice that might be encountered in New York Harbor in winter. Completing the framework of the hull were web frames called stringers or ‘side keelsons’, which connected the frames in a longitudinal direction and which gave added belts of great strength along the hull.

The outer skin of each ship was its shell plating – large steel plates riveted to the frames. On average, the shell plates were 6ft wide and 30ft long and weighed between 2½ and 3 tons each, with the largest being 36ft long and weighing 4¼ tons. The thickness of the plates averaged 1in amidships and thinned toward the ends but was thicker in other areas depending on the need for extra strength. The shell plates were fastened with rivets that were applied both by hand hammering and hydraulic press. It is a common misunderstanding that all of the rivets were hydraulically applied. In fact, hydraulic riveting had its limitations – for example, the massive jaws of the hydraulic riveting machine could not be worked around more than moderate bends in the plates or get into confined areas. More than half a million rivets were used on each double bottom, and the weight of these rivets alone was estimated to be 270 tons. When completed, each ship had about 3 million rivets with an estimated weight of over 1,200 tons.

Hydraulic riveter at work on Olympic’s sheer strake. (Engineering/Authors’ Collection)

Much has been made in recent years of steel that became overly brittle in freezing temperatures, with suggestions that Titanic was somehow flawed in her construction from the start. In reality, the shell plating and the rivets that held them together and fastened them to the ribs were, in the collision with the iceberg, subjected to shearing forces that they were never designed to withstand. Inspectors from the British Board of Trade – an entity entirely separate from the shipyard and beholden to no private firm – rigorously inspected the ship’s riveting in an ongoing basis for tightness and integrity, and any that failed inspection resulted in a deduction from the riveters’ wages. While these steel plates were tremendously strong, the term ‘shell plating’ is quite appropriate as they were only intended to form the ship’s outer shell and were never designed to be impervious to any major collision such as with another ship at speed – or an iceberg.

The lowest part of the hull was formed not by a single layer of steel plating, but by the heavily reinforced bottom structure with the keel as its backbone. With the outer bottom plated with steel to form the ‘skin’ of the ship and the inner bottom also plated, a cellular ‘double bottom’ resulted. The inner bottom was termed the Tank Top, so named because the double bottom, divided as it was by the keel and its longitudinal and transverse members, was comprised of forty-four separate watertight compartments. These compartments were used as tanks to carry water for ballast, boiler feed, and for domestic use. In addition to holding water, the double bottom added to the safety of the ship. As the Tank Top formed a second skin, it could save the ship from sinking if the ship struck a sunken obstruction or ran aground. Even with the outer bottom torn open, the watertight inner bottom would limit the flooding to the tank space and prevent entry of water into the holds or machinery spaces.

The principal safety feature of the Olympic-class ships, and certainly the one that gave rise to the ‘unsinkable’ myth, was the division of the space within the hull into sixteen watertight compartments by strong transverse watertight bulkheads. The forward, or collision, bulkhead was carried as high as C Deck, whereas those from the forward end of the reciprocating engines and aft were carried to D Deck. The remainder of the bulkheads – the ones between the boiler rooms amidships – only went as high as E Deck, but the lowest of these (there being a slight rise, or sheer, fore and aft from amidships) was still almost 11ft above the maximum-load waterline. This arrangement would allow Olympic and Titanic to easily survive a breach of two adjacent compartments amidships, the damage that would be expected through a collision with another large ship. Furthermore, each ship was capable of remaining afloat with all of the first four compartments flooded, providing ample protection if the ship rammed a floating body in her path. Thus Olympic and Titanic’s builders and owners were confident that their ships would remain afloat even in a worst-case collision scenario, and in fact the ships’ watertight subdivisions met and exceeded many of the regulations for large ocean-going passenger vessels of today. In short: an Olympic-class ship would not be easy to sink.

Access through each of the transverse watertight bulkheads was gained by means of vertical-sliding watertight doors, which were held in the open (upper) position by a friction clutch. The doors could be released by means of a powerful electromagnet that was controlled by a switch on the bridge. These doors could also be closed by a releasing lever at the door itself, or from the deck above. The doors were also coupled to a float-activated switch that would close them automatically in the event that the compartment flooded and the water reached a pre-determined level. Although the speed of each door’s descent was controlled by a hydraulic cylinder, the system was engineered to permit the doors – which weighed nearly three quarters of a ton – to drop the last 18 to 24in unrestricted. This ensured that they would crush or cut any obstruction (such as chunks of coal) which remained in the doorway, which was especially important since several of the watertight doors gave passage through the coal bunkers.

Any ocean-going ship must be designed to rid itself of water that makes its way into the lower part of its hull, and even the watertight Olympic-class ships were no exception. A complex arrangement of piping connected to drain wells along the centreline of the ship in each watertight compartment provided for the removal of water in any area; a slight upward rise of the Tank Top from the centreline outward on each side ensured that any water would naturally flow into the wells. If necessary, the ship’s entire pumping power could be brought to bear on a single compartment, and in an emergency, large volumes of water could be removed from the engine room by utilising the powerful condenser-circulating pumps that cooled the steam from the engines into water that was piped back to the boilers. Combined, either ship’s pumping system could move 1,700 tons (over 400,000 gallons) per hour.

Period image of Olympic showing deck letter designations.

Olympic and Titanic were each fitted with a cast-steel rudder with a weight of 101¼ tons, an overall height of 78ft 8in and a width of 15ft 3in. It is commonly believed that Titanic’s rudder was undersized and was one of the critical design flaws that contributed to the ship’s inability to turn away from the iceberg in enough time to avert disaster. Like many ‘facts’ that often appear in print and online, this is a fallacy. Unlike warships, which had as a design requirement the ability to manoeuvre quickly, ocean liners had no such requirements. When manoeuvring in a narrow channel they normally utilised their engines in conjunction with the rudder, such as going half ahead on one engine while backing slow on the other. In a 1997 report by the Marine Forensics Panel of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, naval architects Chris Hackett and John Bedford stated that: ‘It must also be remembered that, although the rudder area was lower than we would adopt nowadays, Olympic’s turning circles compare favourably with today’s standards.’1 Their conclusion was based on hard data rather than the speculation and conjecture on which statements to the contrary have been based.

Communication with ships and shore was made possible by the Marconi wireless apparatus fitted to a suite of rooms within a few steps of the Navigating Bridge. No longer was a ship isolated at sea when out of sight of other ships; no more did ‘speaking’ another ship require them to heave to within hailing distance. Day or night, fine weather or fog, ships could communicate with each other and have messages relayed to one side of the Atlantic or the other when in mid-ocean. Passengers could enjoy the novelty and convenience of sending messages through the ether, and in fact bridge-to-bridge messages from the master of one vessel to another enjoyed no priority over that of a passenger sending the equivalent of an electronic postcard.

The 5kW wireless transmitter was connected to four parallel aerial wires suspended between the ship’s towering masts. From these aerial wires, cables led directly to the equipment in the wireless room. The wireless installation consisted of two complete sets of apparatus: one for transmitting and the other for receiving transmissions, plus an emergency transmitting set with limited range that could operate independently of the ship’s power supply for 6 hours. The main transmitter had a guaranteed minimum range of 400 miles; however, at night or during certain atmospheric conditions, its range extended to more than 2,000 miles. The wireless apparatus was manned 24 hours a day by two operators holding nominal ranks of Junior Officers with the White Star Line, although their ‘real’ employer was the Marconi International Marine Communication Company Ltd.

For visual signalling, each ship was fitted with two electrically operated Morse lamps mounted on the roofs of the wing cabs outboard of the Navigating Bridge on either side. By pressing a sending key on a portable box plugged into a socket inside either wing cab, an officer could ‘Morse’ another ship via the flashing lamp above. In clear visibility the Morse lamps could be seen at 10–15 miles’ distance. In addition, for distress signalling the ships were equipped with a large number of pyrotechnic rockets, described later in this book.

On their Boat Decks, Olympic and Titanic were each fitted with sixteen pairs of Welin davits, eight on each side of the ship. Rigged under the davits were sixteen wooden lifeboats: fourteen 30ft boats with a combined capacity of 910 persons, and two smaller emergency cutters (25ft 2in) with a combined capacity of eighty persons. The cutters were rigged under the foremost davits near the Bridge and were kept permanently swung out while at sea in order that they could be lowered quickly if needed. It was quite common for large vessels, steaming in excess of 20 knots, to collide with fishing boats on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, and the cutters also had to be kept in readiness in case someone fell overboard.

Each of the ships was also equipped with an additional four Engelhardt collapsible boats (27ft 5in long) with a combined capacity of 188 people. The collapsibles were so named because they had wooden bottoms and adjustable canvas sides that could be pulled up and snapped taut by means of hinged steel braces. Two of the collapsibles were secured to the deck beneath the emergency cutters and the remaining two were secured to the roof of the Officers’ Quarters deckhouse on either side of the No. 1 funnel. The latter could be raised up off the roof and lowered to the deck below by means of block-and-tackles that could be rigged to eyes spliced into the funnel shrouds (guy wires) above them.

Each ship had a total lifeboat capacity for 1,178 persons, well in excess of the official requirements – but more than 2,000 short of the number each ship was certified to carry. Provision of sufficient lifeboats became one of the most contentious issues that arose in the wake of the Titanic disaster. Much of the blame was levelled at the outdated regulations set by the British Board of Trade, which had not been amended since 1894. At the time of the last revision of the Board of Trade lifeboat regulations, the 12,950-ton Cunard vessel Campania was the largest ship afloat. In the years following this revision, no allowance was made for the dramatic increase in the size and passenger capacity of subsequent ships. At the time the plans were drawn for the construction of the Olympic-class ships in 1908, the regulations showed no distinction between the 12,950-ton Campania and the 46,000+ ton Olympic and Titanic. Under the regulations in force at that time, all British vessels of more than 10,000 tons with sufficient watertight subdivisions only had to carry sixteen lifeboats with a total capacity of 7,750 cubic feet; however, the lifeboat capacity on each of the Olympic-class ships totalled 11,325 cubic feet.2 By fitting four Engelhardt collapsibles, the White Star Line actually exceeded the Board of Trade requirements by 46 per cent.

A period advertisement for the Welin quadrant davit.

The Welin double-quadrant davit, showing its capability to accommodate an inboard row of lifeboats.

While the Board of Trade requirements were outdated, the White Star Line was by no means alone in its belief that more lifeboats would be unnecessary. In 1912, the need for ‘lifeboats for all’ was never seriously considered by many. Since the second half of the nineteenth century the flow of shipping across the Atlantic from New York to England had been known as the ‘Atlantic Ferry’ and for good reason: it was the most heavily travelled sea route in the world. With the advent of the Marconi wireless, ships were rarely out of communication with each other and any ship in distress could count on others coming to her aid long before she was in danger of foundering. Thus, in 1912, the utility of lifeboats was seen in their ability to convey passengers to a nearby ship rather than to provide a refuge for all aboard. It was considered inconceivable that a ship could ever founder with such rapidity that all persons would need to be taken off at once, rather than shuttling passengers to other vessels and then returning for additional loads. Even after the Titanic disaster, the author of Practical Shipbuilding, a widely respected authority on large steel-ship construction, opined that when a ship had been designed to remain afloat after the worst conceivable accident, ‘the need for lifeboats practically ceases to exist, and consequently a large number may be dispensed with.’3

The Welin double-acting davits had been designed to attach and lower three lifeboats in succession and could easily have been adapted to increase this number to four. After launching the boats beneath them, the davit arms could be cranked inboard to be rigged to additional boats nested there. It is stated that during the significant planning stages of the Olympic and the Titanic, between 4 and 5 hours were devoted to discussing the ships’ interior fittings and decor, with only 10 minutes given to discussing lifeboat capacity. Harland & Wolff’s chief naval architect, Alexander Carlisle, had grave misgivings about the British Board of Trade’s seemingly outdated lifeboat regulations. Carlisle’s original sketch incorporated a provision for sixty-four lifeboats, which would have been sufficient for all on board; however, as discussions proceeded between Harland & Wolff and the White Star Line, Carlisle was obliged to modify his original plans. The number of lifeboats for Olympic and Titanic was first reduced to forty-eight, then to thirty-two, and then, some time between 9 and 16 March 1910, to only sixteen – the minimum number required by the Board of Trade.

Titanic’s palatial First-Class passenger accommodations are well known and photographs of her public rooms and staterooms appear in countless books. They were luxurious indeed, and rivalled the finest hotels and restaurants ashore. Walnut, sycamore, oak and satinwood panelling were used liberally in the best First-Class rooms; imitation coal fires providing electric heat burned within wrought-iron grates set within ornate fireplaces; and stateroom washbasins were mounted in veined marble. Electric lighting and electric heat – all within the passenger’s control – added to the comfort, and bell pushes could conveniently summon a steward to provide a cup of tea or anything else that was desired.

First-Class Stateroom B–59 on Titanic. (H&W/Daniel Klistorner Collection)

The culinary facilities of the Olympic-class ships were no less impressive. The First-Class Dining Saloon could seat 554 passengers in one sitting, yet the service did not suffer from catering to such numbers: there was, on average, one steward for every three passengers. The galleys were immense and served everything from roast duckling to Waldorf pudding. A separate à la carte restaurant catered to passengers who did not want to dine according to a fixed schedule or partake of set courses, and passengers in either dining venue had their choice of wine, mineral water, cigars, fresh fruit, ice cream … virtually any drink, dish or delicacy found ashore could be had in First Class on Olympic or Titanic.

No less luxurious were the accommodations for Second and Third Class. Far from being in steerage, Third-Class passengers slept and dined as well as Second-Class accommodations on other ships, and better than on some. Clean linens, separate cabins, and meals served at table by stewards were the standard in Third Class. Making their new ships attractive to prospective emigrants was not out of compassion, but was good for business: despite the prices paid by First-Class passengers, which equalled the proverbial king’s ransom for the finest suites, emigrant traffic was the bread and butter of the transatlantic steamship trade. While the Olympic-class ships could carry 735 in First Class and 674 in Second Class, they were designed to carry 1,026 Third-Class passengers. Without the income realised by the passage of emigrants in large numbers, neither the White Star Line nor any other major steamship company would have been able to afford these palatial liners.

The carriage of passengers was not the only income realised by Olympic and Titanic, however. Each ship could carry nearly 2½ tons of cargo in three spacious holds, and while no bulk cargoes were carried, bags, barrels, cases and crates in various quantities could be readily accommodated. Even motor cars could be carried, appropriately crated. No less important was the carriage of Royal and US Mail under contract to their respective governments, with ‘RMS’ before the ships’ names to designate them as Royal Mail Steamers. There was even a special strong room for specie (coin money) and bullion. 268 tons of mail, parcels and specie could be carried, with four to eight British and American Sea Post clerks employed aboard to sort the thousands of bags of mail carried on each trip.

All in all, the Olympic-class ships were the pinnacle of shipbuilding achievement and would be highly profitable for their owners, and the White Star Line’s prestige and prominence was riding on them. To have one damaged beyond repair – an event that would not be covered by insurance – would be catastrophic. As fate would have it, however, less than four months after Olympic’s maiden voyage, an unexpected event would take her out of service for a period of two months. Would it be grave enough to imperil the ship’s future?

2

OLYMPIC AND TITANIC

Work on the construction of Olympic – Harland & Wolff yard number 400 – commenced on 16 December 1908. By New Year’s Day a few weeks later, her hydraulically riveted keel had been completed. By this time the workforce at the shipyard had grown to well over 10,000. Three months later, when the keel of her sister ship Titanic was laid in the adjacent slip, the workforce had increased to by an additional 4,000 men. However, it should be noted that not all of these workers were actively engaged in the construction of these two ships. Harland & Wolff had contractual arrangements with other shipping companies, and work on those contracts proceeded in other parts of the yard. Approximately 6,000 men were directly involved with the building of the Olympic-class ships, about one-sixth of whom were on nightshift.

While work on Olympic and Titanic was in progress, construction was underway on two new White Star Line tenders to service the new leviathans at Cherbourg. Because the Olympic-class ships were too large to dock there, tenders would be required to ferry passengers, mail and baggage between ship and shore. These new tenders, Nomadic and Traffic, were purpose-built for this role and would be kept at Cherbourg.

After Olympic’s keel was laid, work proceeded at a brisk pace. Photographs reveal that by late November 1909 all but the last of the ship’s frames had been raised into position. By late April 1910 her hull was completed. As with the ship’s keel, hydraulic riveting had been adopted whenever possible. The seams of Olympic’s bottom hull plating were double riveted (two parallel rows of rivets where two shell plates met), whereas the topside hull plating had been triple and quadruple riveted for extra strength.

Over the course of six months, work continued within the hull. This included the laying of deck plating, installation of the transverse watertight bulkheads, plumbing, electrical work, and the fitting of auxiliary equipment. The ship’s heavy machinery such as boilers and engines would be lowered into the hull after the ship had been launched. For this reason the ships were not launched with their funnels installed, as the heavy machinery would be lowered into the hull through large openings in the funnel casings.

In this image taken on 18 February 1909, hydraulic riveters are attaching the vertical floor plates to Olympic’s vertical keel plate. (Authors’ Collection/The Engineer)

By mid-July, steel plating largely covered Olympic’s Tank Top and the stern frames (seen in the background) had been raised into place. (Authors’ Collection/The Engineer)

Titanic and Olympic in mid-August 1910. The plating of Titanic’s hull is well advanced. (Authors’ Collection/The Engineer)

Olympic’s hull is freshly painted, as seen here two weeks before her launch. (Authors’ Collection/Harland & Wolff)

On 20 October 1911 Olympic was ready for launch. Photographs reveal something curious about her appearance: the hull had been painted a very light grey, except for the red ochre-coloured anti-fouling paint applied below the ship’s intended waterline. This was at the direction of Lord Pirrie, who wanted to give the ship a dramatic visual appearance while she slid down the slipway into the River Lagan. The light paint would give the hull an overwhelming appearance of size, providing excellent photographic opportunities for the press to capture what was to be the world’s largest ship.1 Pirrie’s decision to paint the ship’s hull as such was intended to grab maximum press coverage, which would later pay handsome dividends as the photographs were seen worldwide. Following the launch, Olympic’s hull would be painted with the traditional graphite-grey undercoat above her waterline, eventually to be followed by her final coats of black for the majority of the hull and white on the uppermost strake. The practice of painting the ship’s hull in a very light-coloured paint was a common shipyard practice for the first of a class or for a special ship in order to draw attention to the launch. Olympic’s sisters Titanic and Britannic would both be painted in their standard colours when they were launched.

Olympic at time of her launch, 20 October 1910. (Authors’ Collection/Harland & Wolff)

Titanic prior to launch on 31 May 1911. (Charles Milner/Harland & Wolff)

It was stated that on 20 October 1910 well over 100,000 people witnessed the launching of Olympic, with the press, dignitaries, and senior management of Harland & Wolff and the White Star Line present. Olympic’s launch weight – excluding the launch cradle at the bow that would keep her upright – was 24,600 tons, and the downward pressure on the bearing surface would be 2.6 tons per square ft. To lubricate the slipway and reduce the friction on the ways, some 15 tons of tallow and 3 tons of train oil mixed with 3 tons of soft soap were used. Just before 12.15p.m. the last of the supporting shores had been removed, leaving Olympic resting solely on the fore and aft poppets and the sliding ways. Only 62 seconds after the launch triggers had been released the ship gracefully slid stern first into the river. The 24,600-ton hull reached a maximum speed of 12½ knots before being brought to a standstill by six anchors and 80 tons of drag cable and chain.

At 12.15p.m. on 20 October 1910, Olympic was successfully launched. (Charles Milner/Harland & Wolff)