11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

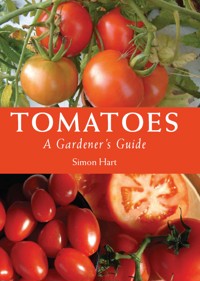

The tomato is a popular and versatile choice in the garden. It is vibrant, nutritious and delicious. It can be grown from hanging baskets with herbs, can yield prolific crops, and can cheer up a summer salad with its red, yellow, orange or green hues. This practical book explores all aspects of growing tomatoes from cultivar selection and plant raising, through outdoor and protected crop production, to plant care and training. It also advises on what to do if things start to go wrong. Topics covered include: Tomato history Guide to choosing cultivars Ideas for growing tomatoes Advice on greenhouses Instruction on pests and diseases

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 218

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

TOMATOES

A Gardener’s Guide

Simon Hart

First published in 2010 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© Simon Hart 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 732 8

Photographic Acknowledgements

All photographs by the author, except where otherwise credited: frontispiece and pages 6, 13, 42, 106 and 121 © Rhoda Nottridge; pages 11 and 16 © Tony Bundock; page 25 © Sue Bunwell and Andrew Davis; pages 26, 114, 115 and 116 © Delfland Nurseries. Photographs on pages 7, 8, 10, 21, 22, 37–39, 44, 56, 57, 62, 64, 76, 85, 88, 107 and 117–119 were taken in the greenhouses of Writtle College, Essex.

Illustrations by Caroline Pratt

CONTENTS

1 TOMATO HISTORY

2 THE TOMATO PLANT: PHYSIOLOGY AND VARIETIES

3 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF TOMATO PRODUCTION

4 PLANT RAISING

5 HOUSING YOUR TOMATOES

6 CROPPING INDOORS AND OUT

7 PLANT TRAINING AND ROUTINE OPERATIONS

8 IRRIGATION AND FERTILIZATION

9 PESTS, DISEASES AND DISORDERS

10 TOMATO MISCELLANY

FURTHER INFORMATION

INDEX

Nutritious and delicious, the tomato is a favourite crop for the gardener.

1 TOMATO HISTORY

The original wild tomatoes come from South America, and can still be found in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile and Colombia. Rather oddly there is no word for the plant in early South American Indian languages, and certainly no record of its cultivation, so it seems unlikely that any of the early local inhabitants found a use for it. Of the thirteen wild species considered as ‘tomatoes’, no single one of these is recognized as being the direct ancestor of the modern cultivated tomato, though genetically the closest relative is the tiny fruited Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium, or redcurrant tomato.

The first cultivation of the tomato appears to have been by the Aztecs in what is now Mexico, some 2,000 miles distant from its native region. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived they found an advanced agricultural system, and yellow-fruited tomatoes being grown. How the Aztecs got their hands on the original plants from 2,000 miles away is something of a mystery, though a believable theory is that over time, seeds of the plants would have had found their way into the area courtesy of migrating birds. Tomato seeds are well known for their ability to pass through the digestive tract, as the stories of bumper crops of tomato plants found at sewage treatment works will support.

The tomato made its way into Europe, and also into Spanish colonies in North America and the Caribbean, in the very early 1500s, although some attribute its introduction into Europe to Columbus as early as 1498. As the first tomatoes to appear in Europe were the yellow-fruited form, they gained the name pomo d’oro’ or ‘golden apple’, which remains the same in Italian to this day. The tomato gets a mention in several of the early herbals from the mid-1500s and 1600s. Writing in 1550, Pier Andrea Mattioli used the Italian name ‘pomodoro’ – but he also mentioned that there was a red form of the fruit.

Initially no one seemed particularly impressed by the fruit; though edible it was identified as a close cousin of the deadly nightshade, so became regarded as slightly suspicious, if not quite as dangerous as its relative.

The date of the introduction of the tomato to England is usually given as 1596, but was almost certainly earlier as the first description of the fruit in the English language came courtesy of John Gerard in his Herball of 1597. Gerard was also fairly unimpressed, writing: ‘In Spaine and those hot regions they used to eate the apples prepared and boil’d with pepper, salt and oyle, but they yeeld very little nourishment to the bodie.’

‘Black Russian’, an interesting old heritage cultivar.

Lycopersicon penellii – a ‘wild’ tomato.

By the end of the sixteenth century the redfruited form had become more commonplace, and in England had picked up the common name ‘love apple’; the reason for this is lost in history, possible theories ranging from the associations with the red colour of the fruit, to a misinterpretation of the name ‘pomodoro’ as ‘pomi de moro’ (‘apple of the Moors’, or ‘Spanish’) and then to the French ‘pomme d’amour’. Whatever the origin, a reputation for aphrodisiac qualities stuck by association, and consequently the English were a bit nervous about eating the fruit, growing the plant principally as a botanical curiosity and for its ornamental value. (Interestingly the potato once commanded high prices in parts of Europe due to its reputation as an aphrodisiac, though this is more likely to have been a cunning bit of marketing than something connected with the Solanaceae in general.)

There does not appear to be a particular point at which the tomato made the transition from ornamental to edible; it is most likely that it caught on gradually. Hannah Glasse’s cookbook The Art of Cookery of 1758 lists a tomato recipe.

Flowers of Lycopersicon penellii.

It took until 1822 for the first specific instructions for the cultivation of the tomato to appear, by which time they were already being produced for sale in the south of England, though their popularity was not great. In William Cobbett’s The English Gardener of 1829 the whole subject of the production of ‘tomatum’ is disposed of in half a page, whereas the other salad staple, the cucumber, is indulged for a full nine pages. Cobbett appears fairly disinterested in the tomato, writing: ‘The fruit is used for various purposes, and sold at a pretty high price.’

AGREEING ON A NAME

In the novel Lark Rise to Candleford (set in the late 1800s) Flora Thompson describes the first appearance of red and yellow tomatoes on the local peddler’s cart, saying that they had ‘Not long been introduced into the country, and were slowly making their way into favour’. Struck by the colours, the girl Laura asks what they are, and is told: ‘Love apples, me dear, love apples, they be; though some hignorant folk be calling them tommy-toes.’ The name ‘tomato’ appears to have come by a rather roundabout route from the Aztec Xitomatl or Tomatl, via the seventeenth-century Spanish tomate, by way of tomata in England and America in the 1800s (Dickens uses the word ‘tomata’ in The Pickwick Papers) to the tomato’ of today.

Latin Origins: the Edible Wolf Peach

The Latin name given to the tomato is Lycopersicon esculentum, which translates as the ‘edible wolf peach’. The origin of the name Lycopersicon is attributed to the Greek naturalist Galen (129–207AD), but whatever plant Galen was describing it certainly wasn’t a tomato, as they didn’t appear in the Mediterranean area for another 1,400 years. How the tomato took the name Lycopersicon appears to stem from its similarity (particularly in the appearance of the fruit) to another famous member of the Solanaceae family, the belladonna or deadly nightshade. In Germany it was believed that witches used belladonna to conjure werewolves, so Germans considered the name wolf peach quite appropriate.

Linnaeus (1753) classified the tomato as Solanum lycopersicon, but Tournefort (1694) had already considered the tomato to be a distinct and separate genus, Lycopersicon. Consequently the name Solanum lycopersicum is still occasionally found, but Lycopersicon esculentum is the accepted botanical name. The actual taxonomy or botanical classification of tomato is still far from clear, particularly concerning the ‘wild’ types of tomato. The classification developed by C. H. Muller in his ‘A revision of the genus Lycopersicon’ of 1940 is still commonly used. Muller divides the genus into two sub-genera Eulycopersicon and Eriopersicon, putting L. esculentum into the first sub-genus, as shown below:

Young deadly nightshade plant Atropa belladonna.

Genus: Lycopersicon Sub-genus: Eulycopersicon

Lycopersicon esculentum

Lycopersicon esculentum Pyriforme – pear-shaped tomato

Lycopersicon esculentum Cerasiforme – cherry tomato

Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium – redcurrant tomato

Whatever the taxonomists eventually end up agreeing on, it is very convenient that all the ‘wild’ types of tomato are capable of being crossbred with the cultivated types (though sometimes this is difficult to achieve), representing a great genetic base for continued crop improvement.

FROM HUMBLE BEGINNINGS TO THE TOMATO OF TODAY

The slow acceptance of the fruit in England – even after the reputation for being a slightly poisonous aphrodisiac had worn off – can be put down to a number of reasons, principally availability. Obviously production was seasonal: in the open ground or walled garden the fruit would only be available in quantity for three months of the year, and production in glasshouses did not start on a commercial scale until the very late 1800s. The first records of tomato crops from the emerging glasshouse industry in the Lea valley (just north of London) date from 1887.

Ripe deadly nightshade berries.

The fruit of lycopersicon penellii – hairy fruit is typical of the Eriopersicon types, or wild tomatoes.

Initially tomatoes would have been more available to city dwellers, as market gardens with greenhouses developed on the fringes of large urban conurbations. The expansion of the railways, increased supplies from the Channel Islands, and the developing greenhouse industry on the south coast of England steadily widened availability. In America, where the tomato had become very popular from the mid-1800s, the growers had a lucky break: in 1893, flying in the face of botanical facts, the US supreme court classed the tomato as a vegetable rather than a fruit, and as all imported vegetables were taxed at the time (whereas fruits were not), supplies from Cuba and Mexico dried up, leaving the way clear for domestic growers to fill the supply gap.

The emerging greenhouse industry took to the tomato as a useful summer crop, grown in rotation with leafy salads and cut flowers, but under the government’s push for food production during World War II it really came of age as a greenhouse crop producing a fruit valuable in the diet for a nation short of its usual sources of vitamins from imported fruits. The gardening public were obviously aware of the value of the tomato: the Ministry of Agriculture’s Allotments and Garden Guide for June 1945 states that according to their information, the tomato is ‘Crop no.1 with war-time gardeners and allotment holders’. Today, with gardens getting smaller, the versatility of the tomato to a range of different cultivation methods is even more apparent. It is reported that 90 per cent of gardeners in the USA cultivate tomatoes.

The annual world production of the tomato is in the region of 110 million metric tonnes from 4.4 million hectares of land, with China being the biggest single producer, followed by the USA.

There is, of course, a world of difference between the production of processing tomatoes, grown as an agricultural crop on a field scale for mechanical harvest, and the production of fresh or salad tomatoes, which are mainly produced as a greenhouse crop. Rather strangely it is countries in northern Europe, a region not climatically ideal for tomato production, that produce the highest yields per hectare by using heated greenhouses, with the Dutch being the leaders in this type of production.

THE TOMATO: FOOD, SUPER FOOD OR MEDICINE?

Considering that many of its cousins in the Solanaceae yield a whole raft of medicinal substances, to date not much use has been made of the tomato in medicine – the juice of the tomato leaf and stem was first used in the sixteenth century to treat skin diseases, but it was not until the 1940s that it was discovered that a substance in the leaves, named tomatine, did halt the growth of fungal disorders such as athlete’s foot, and soaps containing leaf and stem extract were marketed for the very purpose. Tomato soaps are still available today, but containing fruit extract and citing the vitamin and anti-oxidant content as being good for the complexion.

Modern large-scale greenhouse tomato production.

Enter Lycopene

In the USA, patent medicines containing tomato were peddled by the ‘snake oil’ salesmen of the old West as general cure-alls. Few of these made any commercial impression, but ‘Dr Milne’s Compound Extract of Tomato’, which today would be recognized as tomato ketchup, was probably closer to something with actual medicinal value than the charlatans of the time realized, on account of its lycopene content. Lycopene is a red carotenoid pigment that occurs in a number of fruits, and was first identified in the tomato in 1875. In more recent times it has been recognized as a strong antioxidant and possible anticarcinogen. Lycopene is more available in cooked tomatoes and tomato products (pastes, ketchups) than in the fresh fruit, and as it is fat soluble, tomato products or dishes that include oil also help its absorption.

Gathering a belladonna crop on a UK Materia Medica farm in the 1920s.

CLOSE FAMILY – OTHER SOLANACEAE OF INTEREST

A strangely diverse family providing everything from valuable food crops to deadly poisons, twenty-five species of Solanum provide staple crops in various parts of the world, though of these only four are grown on a commercial scale in the UK and US: tomato, potato, aubergine or eggplant, and capsicum or pepper. The potato Solanum tuberosum provides more calories per unit area of ground than any other food crop, and is the world’s most widely consumed vegetable.

The well known poisonous arm of the family, which includes deadly nightshade and henbane, gives us a whole collection of useful drugs used in everything from heart surgery to remedies for seasickness. Both plants were once commercially grown in the south and east of England. The other famous Solanum, tobacco, remains the most important world non-food crop in economic terms.

Many other Solanaceae have yet to realize their full potential, but are currently creating interest as possible new crops; for example, some leafy species of nightshade native to Africa (close relatives of the UK’s black nightshade Solanum nigrum), far from being poisonous, are regularly eaten, and are particularly high in vitamins and minerals.

The native black nightshade Solanum nigrum – a common enough summer weed in the UK and mildly poisonous, though the related African Solanum scabrum is edible, and the leaves are used like spinach.

The indeterminate, or cordon, tomato is the most commonly-grown type grown in both the greenhouse and the garden.

2 THE TOMATO PLANT: PHYSIOLOGY AND VARIETIES

Tomatoes are short-lived perennial plants, which for practical purposes are treated as annuals. In the UK they are classed as tender plants, as they cannot tolerate frosts.

TOMATO PLANT TYPES

The cultivated tomato of today exists in two basic plant forms: the indeterminate and the determinate.

The Indeterminate Type

In the UK the most familiar type is the indeterminate – sometimes known as cordon – as this is the main type grown both commercially as a greenhouse crop and in the back garden. The plant produces a single stem, which appears to have a single growing point from which all extension growth comes. Indeterminate tomatoes usually produce seven or eight leaves before the first flower truss forms, thereafter producing a truss after every two leaves. The number of flowers and therefore fruit that each truss produces is cultivar dependent, but sometimes the first truss on early planted tomatoes is branched (so giving potentially more fruit), whereas later ones are not. The plant also produces lateral growth or side shoots from axillary buds, so left to its own devices soon becomes an impressive spreading vine. For practical purposes the sideshoots are removed on a regular basis restricting the plant to a single stem, which is then trained up a string or stake. At one time this type of training system picked up the name ‘cordon’ as it resembles the way single-stemmed cordon apple trees are trained. Some seed merchants describe indeterminate tomato cultivars as cordon types.

When grown in this fashion as a commercial greenhouse crop, the stem can reach 12–14m (40–45ft) in length over a season.

TRAINING INDETERMINATE TOMATOES

There is no actual need to follow commercial practice and restrict the plant to a single stem when growing indeterminate types, though in a greenhouse it does make sense for ease of management. When grown outdoors indeterminate tomatoes can be grown as multi-stemmed plants by allowing the development of sideshoots, or even used as a feature to cover trellises and similar structures in the way that Victorian gardeners would have used them.

The Determinate or Bush Type

In the UK, the determinate type is perhaps less familiar to gardeners. The plant grows initially as a single stem that produces a flower truss followed by one to two more leaves, then extension growth stops. Further vegetative growth then comes from lateral shoots, which also stop growing when flower trusses form. This gives a short plant of bushy appearance, with the final height depending on the cultivar. As the flower trusses develop more or less simultaneously, this means that most of the fruit on the plant ripens over a relatively short period. This trait makes determinate tomatoes very useful in northern latitudes with short growing seasons, and has been further developed in cultivars grown for processing, allowing a one-off destructive harvest in which the plants are pulled up and the fruit combed off mechanically. When grown outdoors under UK conditions, determinate types give the earliest fruit from a spring planting.

Type Variations

There are also cultivars listed as semi-determinate types: these grow initially like an indeterminate, producing a single stem with several flower trusses, but eventually the stem forms a final flower truss and stops extension growth. It then behaves like a bush tomato, with further vegetative growth coming from the sideshoots. Whereas it is often possible to get away with not providing plant supports for indeterminate types, the vigour and tall growth of the semi-determinates will definitely make support necessary.

Dwarf and miniature novelty types are indeterminate, with very short internodes and a strong stem that makes them essentially self-supporting.

TOMATO FRUIT TYPES

The tomato fruit is botanically classified as a berry. Cutting a standard round salad tomato in half transversely will show the fruit is made up of two, or in larger fruit, three sections (called ‘locules’), divided by thin walls. The locules contain the seeds suspended in a type of jelly. These types of fruit are called bi-locular or trilocular, and are the most familiar fruit type.

Bi-locular fruit.

Tri-locular fruit.

Multi-locular fruit.

Cutting a beefsteak or canning plum tomato in a similar fashion will show that the fruit consists of many smaller locules, the dividing walls are much thicker, and the space for seeds and jelly much reduced: this is called a multi-locular fruit, and is the type preferred for canning and processing as it is firmer and contains more actual ‘flesh’ than the two locule types; it also cooks down to a firm paste.

Fruit shape can be anything from round to elongated, and size from tiny cherry-fruited to monsters weighing in excess of 500g (17oz).

The following are the main fruit types that are recognized commercially:

Beefsteak: The largest type in regular commercial production, the name ‘beefsteak’ originated in the USA, being the brand name that Anderson and Campbell (the first company to can tomatoes, starting in 1869) adopted for their first canned tomato product, which actually consisted of one single enormous tomato per can. These large, ridged, irregularly shaped fruit were sometimes known as ‘cushion’ tomatoes, and are many people’s idea of what an old-fashioned tomato should look like. Modern commercial beefsteak-type tomatoes sold fresh weigh 170–280g (6–10oz), but there are varieties that regularly produce fruit of over 500g (17oz). The world record for the heaviest tomato is held by a monster beefsteak type produced in Oklahoma in 1986, which weighed in at 3.51kg (7lb 12oz)!

Plum-fruited: A distinction needs to be drawn here between the plum-fruited canning tomatoes, grown on determinate plants, and the plum-fruited tomatoes grown on indeterminate plants and sold fresh. The indeterminate types yielding plum-shaped fruit are a relatively new addition to the mainstream market. This category also includes the small-fruited cherry plum or baby plum types, which are often sold vine ripe.

Cherry-fruited: This type has a fruit weight between 10 and 25g (0.3 and 0.8oz), usually produced on long trusses. Modern commercial cherry tomatoes are often the ‘vine-ripe’ type, and sold as an entire truss.

Round-fruited: This is the standard familiar salad tomato weighing 70–110g (2.5–4oz – for the UK and US market, six to eight fruit to the pound), sometimes sub-divided into small round and large round types.

Pear-fruited: These are amongst the earliest known types of tomato (the varieties ‘Red Pear’ and ‘Yellow Pear’ are two of the oldest varieties still around), but have never been produced on any sort of scale. Recently some miniature pear-fruited types intended for vine-ripe production have been introduced.

There are plenty of other types of tomato that differ in shape, colour or both from those mentioned above.

Fruit Colour

Considering that the first tomatoes available in Europe were yellow fruited, it appears a bit odd that the red-fruited form came to dominate the market for so many years – and continues to do so. Many colours are available in the tomato, the fruit colour depending on the content of various carotene pigments; in the majority the ratio of the prominent pigments lycopene (red) to beta-carotenes (yellow-orange) dictates the shade of red. Yellow tomatoes lack the lycopene pigment; the beta-carotene and other carotenes present dictate whether it is bright yellow or yellow/ orange. The rather unusual white tomatoes have flesh that is very pale yellow, which looks white through the translucent skin of the fruit. Similarly pink tomatoes have red flesh and a translucent skin.

Whether one colour of tomato has any nutritional benefit over any other colour is debatable, though recent research has indicated that a form of lycopene found in orange-coloured tomatoes is more easily absorbed than the form that is dominant in the red-fruited types.

Vine Ripe?

For many years the standard way of harvesting salad tomatoes in Europe was to pick them a little bit under-ripe – at the orange rather than the fully red stage. This allowed a reasonable shelf life, and as the fruit was firmer at harvest it would suffer less damage in transit. Many people will remember the days of the first English home-produced tomatoes arriving in the shops looking a rather poor shade of orange.

Plant breeding led to the introduction of ‘vine-ripe’ types in the early 1990s, where the fruit could be harvested fully red-ripe and still have an acceptable shelf life.

This allowed the practice of harvesting ‘on the vine’, where the fruit could be left until an entire truss was ripe, and then the whole truss of fruit snipped off – this dramatically reduced harvesting time, particularly for the cherry-fruited types, and was instrumental in cherry-fruited types becoming a commercially viable crop.

Vine-ripe cherry plum tomatoes as harvested.

WHICH TYPES DO YOU GROW?

To many people, growing your own means producing something a little different to what can be found every day, but it depends on your priorities. Obviously there will be more choice for those who wish to raise their own plants, join a seed exchange, or search out the unusual from tomato enthusiasts, than for those who just want some nice red home-grown tomatoes, and purchase their plants from the local garden centre.

Determinate or Indeterminate?

For greenhouse or polytunnel cropping, the indeterminate types are the preferred choice as they keep on cropping reliably through a long season. For outdoor cropping, and with a planting date sometime in May, then both types have their own merits. Indeterminate types generally do not grow or set fruit particularly well at low temperatures, so a cool early summer will mean a slow start with delayed fruiting, but providing the late blight stays away, plants will continue fruiting right up until the first frosts. They need staking or supporting, and regular removal of the sideshoots.

Determinate or bush tomatoes tend to develop more quickly and to fruit earlier from a May planting, particularly if early summer conditions are cool. Because of their compact growth habit they are easier to protect with fleece or polythene early in the season. They have a spreading growth habit but do not need the same amount of maintenance (in terms of sideshoot removal and training) as the indeterminate types, which can be useful for allotment growers who can only get to their plots at weekends. On the down side they can be reluctant to continue fruiting late into the season, and the early fruit is often the best quality.

Semi-determinates can give the best or possibly worst of both worlds: they tend to fruit earlier than the indeterminates, but like the determinate types do not continue fruiting well into late season. The grower has the option of treating them as a determinate type and growing them as a large bush plant, or restricting them to a single stem by severe pruning of the lateral growth, which gives a fairly short plant with early fruiting capacity that can be useful in pots or where space is restricted.

If space permits it is worth experimenting with all types, trying some determinate tomatoes for early fruiting, and indeterminates for mid- and late summer.

F1 Hybrids

The first F1 hybrid tomato, named ‘Fordhook Hybrid’, was introduced in 1945 by the famous American seed company W. Atlee Burpee. The development came about as the company were making efforts to improve the quality and yield of home garden vegetables in response to the US government’s Victory Gardens initiative.

To many people browsing the seed stand at the local garden centre the term ‘F1 hybrid’ is just a peculiar way of saying ‘expensive’. Certainly with tomatoes, hybrid varieties are a great deal more costly than non-hybrid (technically called ‘open pollinated’) types – so what advantages do you get for your money?