7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

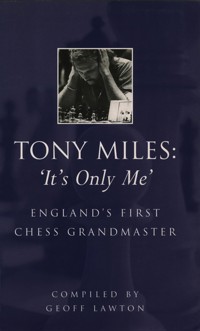

The charismatic Tony Miles has been much missed since his tragic and premature death in 2001. Regarded as one of England's greatest ever chess players and analysts, he was also one of the wittiest writers on the game. By sheer force of example and ebullient peronality, he inspired the 'English chess explosion' after becoming the first UK grandmaster in the mid 70s. This Fascinating collection of over a hundred games and articles, covering Tony's entire chess career, includes his most celebrated wins, a few losses, and in addition to the famous game against Karpov with the bizarre St George's opening 1 e4 a6 - a less well known victory over the then world champion from a television tournament. All the games are annotated by Tony himself - in his own inimitable style. This fitting tribute is rounded off with a review of Tony's original opening repertoire as well as personal appreciations by his Birmingham clubmates and friends Mike Fox, Malcolm Hunt and Geoff Lawton.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 637

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Tony Miles: ‘It’s Only Me’

England’s First Chess Grandmaster

Compiled by Geoff Lawton

Contents

Introduction

Index of Openings

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Leonard Barden

1: The Chess Career of Tony Miles

2: “I played every night for a year until I got bored”

3: “A cable”

4: “I pushed Karpov all the way for first place at Tilburg”

5: “I beat Spassky twice heavily—lovely games, very pretty”

6: “I feel I’m overdue to win some tournaments”

7: “I heard that Karpov felt insulted by my choice of opening” (including Interview at Lone Pine 1980 - 133)

8: “When I play close to home it’s the complex—I play badly”

9: “The Impossible Challenge, Tilburg Interpolis 1985”

10: “I get bored with playing the same thing all the time”

11: “I am nostalgic for the days before computers were invented”

12: Problems

13: Solutions to Problems

14: Articles

15: Memories of a generous soul, a great bloke and a unique personality

16: Tony Miles—one of my best and most loyal friends

17: “Can you show me your game against Karpov where you played 1...a6, please Mr Miles?”

18: “I have no style—I just make moves”

Tony Miles’s tournament, match and England national team record

Index of Opponents

Introduction

In November 2001, the chessworld was shocked by the news that Tony Miles, England’s first—and most influential—grandmaster, had died suddenly at his home in Birmingham at only 46 years of age.

By way of tribute we have now compiled a selection of Tony’s most interesting games with his own commentaries. Also included are some of his most memorable articles such as ‘Has Karpov lost his marbles?’ from Kingpin, together with a number of chess brain-teasers he set his readers and a rare interview he gave at Lone Pine 1980.

The majority of the annotations are taken from Tony Miles’s chess column in the New Statesman which he conducted from 1976 to 1981—a period in which he developed into a world class player—and from his contributions to Chess magazine, first as a budding junior and later as a hardened campaigner on the gruelling chess circuit.

In addition there are a fair number of good games which he never fully annotated in words but only with analytical symbols. Games from Tilburg 1984, probably his finest tournament victory, and thrilling encounters such as Miles-Belyavsky, Tilburg 1986, one of his most famous wins, have been taken from his Informator and Chess Player notes (where we have replaced the symbols with words). We were, however, disappointed not to find comments on more of his instructive games with the English Defence, perhaps his favourite opening. Surely he annotated more than those we have managed to unearth here?

Chapter headings come in the form of Miles quotes which highlight key aspects of his 30 year chess career or specific character traits. Meanwhile the tournament record will provide a basis for further research, since he undoubtedly played more events than those listed here. We have also endeavoured to give a glimpse of Miles the man, through our own personal recollections, particularly relating to his school years and his contributions to junior chess in the Midlands.

Throughout the book, unless otherwise stated, any commentaries or quotes are by Tony himself.

Finally, in case you didn’t realise, “It’s Only Me” is an anagram of Tony Miles, and was one of his handles on the Internet Chess Club.

We feel fortunate to have known Tony and it has been a pleasure to compile this book in his memory. We do hope it does him justice and that readers will enjoy his colourful writing and chess annotations.

Index of Openings

(numbers refer to games)

Benko Gambit

15, 21

Caro-Kann Defence

73, 80

Dutch Defence

114

English Defence

26, 39, 42, 105, 116

English Opening

12, 17, 22, 32, 35, 37, 38, 43, 72, 75, 82, 88, 91, 106

French Defence

50

Giuoco Piano

47

Grunfeld Defence

78

King’s Fianchetto

59

King’s Indian Defence

20, 63, 95, 96

Max Lange Attack

2

Modern Benoni

34, 52

Modern Benoni Reversed

54

Modern Defence

112

Nimzo-Indian Defence

19, 62, 84, 89

Nimzovich Defence

74, 97, 98, 102

Old Indian Defence

61

Pirc Defence

10, 90

Queen’s Gambit Accepted

33, 46, 56, 83, 117

Queen’s Gambit Declined

64, 93

Queen’s Indian Defence

44, 45, 48, 49, 66, 67, 70, 79, 81, 94

Réti Opening

7, 8, 57, 60, 113

Ruy Lopez

5

St. George’s Defence

58

Scotch Game

100

Sicilian Defence

1, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11, 13,14, 16, 18, 27, 30, 31, 36, 41, 51, 53, 55, 65, 68, 69, 71, 77

Slav Defence

103, 104, 115

Tarrasch Defence

40

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to Tony Miles’s family, particularly to his cousin Pam and his late Aunt Dev, who unfortunately passed away shortly after Tony. They generously gave us their time and access to his archives.

The following publications have given their permission to reproduce Tony Miles’s work:

New Statesman magazine

Miles’s chess column ran from mid 1976 to early 1981.

Games 9, 22 to 25, 27 to 30, 32 to 35, 38 to 41, 43, 44, 46, 51 to 68.

Articles: ‘Noise at Hastings’, ‘Russian Prodigy’, ‘Kasparov at the Olympiad’, ‘Making sense of chess books’

Problem Numbers: 2 to 18.

New In Chess magazine

‘The Impossible Challenge’—Tilburg Interpolis 1985 tournament report.

Games 83 to 88, 114.

Chess magazine

Early games up to around the time of Dubna 1976, and again from around 1994 onwards:

Games 3 to 8, 10 tol2, 19, 76 to 78, 96, 98 to 103, 105, 107 to 113.

Article: ‘Blindfold Simultaneous Exhibition 1984’, ‘Tony Miles says...’

Audio Chess

‘Tony Miles Grandmaster’—Tony talking to Mike Basman about Dubna 1976.

Games 15 to 18.

‘Chess Café website’

Miles’s column started in 1999.

Games 115, 117, 118.

Article: ‘The Holey Wohly?’

Kingpin magazine

Article: ‘Has Karpov Lost His Marbles?’

Book reviews: Unorthodox Chess Openings, Secrets of Minor-Piece Endings, Samurai Chess: Mastering the Martial Art of the Mind

Informator

Games 21, 36, 37, 45, 69 to 72, 75, 79 to 82, 89, 94, 95, 97, 104, 106, 116.

Inside Chess

Games 90 to 93.

‘The Chess Player’ Series (Tony Gillam)

Games 13, 14, (15 to 18 exclams). Part of the introduction to Miles-Larsen, London 1980, is taken from London 1980 by Tony Miles.

Annotations have been reproduced from the following publications:

Chess Express (defunct)

Games 73, 74.

International Chess (defunct)

Games 42, 47 to 50.

IBM Schaktoernooi

Games 20, 31.

Main sources for quotes

Miles’s quotes are taken from the New in Chess interview with Miles in 1984, S.W.Gordon interviews with Miles from 1976 and 1980, Chess, British Chess Magazine, New Statesman, Chess Life, Best Games of the Young Grandmasters by Kopec & Pritchett, London 1980 by Miles, National newspapers, Birmingham Evening Mail, and BBC TV programs.

The following people have provided help and advice

Jimmy Adams, Michael Basman, James Coleman, Chris Duncan, Malcolm Pein (Chess & Bridge Ltd), Leonard Barden, Bernard Cafferty, Roger De Coverly, John Donaldson, Tony Gillam, Bill Gordon, Stephen Gordon, Bill Hartston, Richard James, Nigel Johnson, Andrew Morley, Richard Parsons, Jodie Soame (New Statesman), Monica Vann, Roelof Westra.

References

New Statesman magazine, Chess magazine, British Chess Magazine, New In Chess magazine and Yearbooks, Informator volumes, Chess Café website, Kingpin magazine, The Chess Player Series, Chess Life (USA), Inside Chess (USA), Internet Chess Club, Chess Assistant: Miles’s database (Monica Vann), The English Chess Explosion from Miles to Short Keene & Chandler, British Chess Botterill, Levy, Rice, Richardson, Best Games of the Young Grandmasters Kopec & Pritchett, European Junior Championship Groningen 1972 tournament book, Tony Miles Grandmaster audio cassette (Audio Chess UK), 1976 taped conversation with Stephen Gordon (National Open 1976), IBM Schaaktoernooi 1976 tournament book, IBM Schaktoernooi 1977 tournament book, London 1980 Tony Miles, London 1980 Hartston & Reuben, Tilburg Interpolis 1984 tournament book, The Master Game James & Barden, The Master Game (book 2) James & Hartston, The Sicilian Dragon Miles & Moskow, The English Defence King, MCO Tenth edition Korn, Modern Opening Traps Chernev, A Complete Defence for Black Keene & Jacobs, Best Chess Games 1970–1980 Speelman, Endgame Strategy Shereshevsky, Birmingham Evening Mail/Post and national newspaper archives (Birmingham Central Library).

Foreword

by Leonard Barden

Tony Miles was the chess player who inspired English talent to defeat Soviet grandmasters and even challenge them for world supremacy. He was a competitive professional, a source of fresh and original opening ideas, a patient strategist ready to win in 100 moves, and a first prize winner at the highest level. Yet Miles never forgot his roots, competing on the English weekend circuit in his prime and later leading Slough to national team titles.

I recall an early image of Tony and his fierce will to succeed, when he played Kuzmin in the England v USSR match in the European championship at Bath 1973. Kuzmin was a bruiser, hard-faced and muscular, while Tony already had his trademark mannerisms as he poured his glass of milk and placed his wristwatch over his score sheet to hide his notation, which he recorded in Cyrillic to Kuzmin’s evident bewilderment. They whipped out their moves staccato, and as time pressure loomed at the end of the session play became almost physical as they leaned towards each other like a couple of heavyweights.

Tony’s schoolboy talent blossomed around 1970 at just the right time for himself and for British chess. Older masters were retired or past their best, while a younger group led by Keene and Hartston seemed unlikely to scale the heights. Abroad, Fischer and Larsen were defeating Russians in a style which excited the chess public. The search was on for an Englishman who could also take on the Soviets.

Jim Slater, then the City’s most dynamic young financier, was already backing a talent programme and an English bid for the junior World Championship. After his money saved the Fischer v Spassky match in Reykjavik from collapse, he offered a £5,000 prize for the first English grandmaster. Slater considered going further with £10,000 for an Englishman reaching the world top 30, but decided to wait. Just as well, since his business collapsed in the next two years and the higher prize could not have been honoured.

The race with Keene for the Slater award triggered a fresh advance in Tony’s strength. In 1976 he tied for first with Korchnoi at Amsterdam, in 1977 he was second to Karpov at Tilburg and in the BBC Master Game, and in 1978 he brilliantly beat Spassky at Montilla. So Tony concluded that “the only thing left is to have a go at Karpov”.

I’m not sure if it was a wise move to make this public. As post- glasnost documents revealed, the Soviets had a dedicated programme to try to stop Fischer, and I have the impression that after 1978 USSR grandmasters played specially hard against Miles. This clearly happened at the 1979 Riga Interzonal where Tony (whose preparation had typically been a few UK weekenders) started among the leaders but then fell back when he met the Russians. His famous win over Karpov at Skara 1980 was an exception to the World Champion’s convincing victories in many of their other games at this time. Karpov’s post-game fury when he branded 1 e4 a6 as lese majeste is consistent with shame at letting the side down by failing to subdue the Western upstart.

After Riga, Miles tacitly abandoned his pretentions to the world crown and played to his strengths as a top GM. He again beat Karpov in the BBC Master Game 1983, while his first place at Tilburg 1984 was the finest British tournament result by anyone up to that time. He totalled 8/11, was 1½ points clear of the field, and defeated three world candidates. At Tilburg 1985 he injured his back, played stomach down on a massage table, and reduced his opponents to a petition against the table.

Miles’s vintage period ended with his ill-health and his ‘22-eyed monster’ defeat by Kasparov in 1986. A decade later, he relaunched his career by combining tournament play with coaching, writing, and leading the Slough team. He won the Capablanca Memorial in Cuba three times, and gained many new admirers with his witty Chess Café internet column and his contributions to Kingpin magazine. He poked fun at the pretentious, and put forward constructive ideas to improve the world chess scene. The humour and warmth of Miles the man comes through in his writing.

Tony’s legacy to British chess can be seen in the successes of our players in the two decades after he won a world title and beat the reigning World Champion. He broke the barrier of over-respect for Russians, and set a high achievement target for his friends and contemporaries. Tony showed that in chess you have to demand the best from yourself, and that became the English chess ethos. Michael Adams, Nigel Short, Jon Speelman, John Nunn and Matthew Sadler are only the cream of many who over-fulfilled what could have been reasonable expectations from them when they were juniors. In his final years Tony was passionately involved in junior coaching, so I hope this book will help inspire future generations of English talent to aim for the heights.

1: The Chess Career of Tony Miles

Tony Miles was born on St.George’s Day—April 23rd 1955, in Edgbaston, Birmingham—the son of Jennie and Jack Miles.

‘I learned to play from my father at age five. I played every night for a year until I got bored. I then ‘retired’ for three years. My life in chess really began as a type of accident, since I started playing at school when I was nine. There was a chess craze at the time and I found that I was good at the game. I always beat everyone, including teachers.’

From the age of 11 he played competitive chess several times a week. This was the beginning of a pattern of intense chess activity that was to last his whole career. The young Miles loved all kinds of sports—rugby, cricket, swimming, athletics—but in the field of chess came the realization ‘I had something special.’

At 11 he won the Birmingham Primary Schools Championship, and subsequently joined the Birmingham Chess Club, where some of the stronger players encouraged the promising schoolboy—in particular Bernard Cafferty and Peter Gibbs, even if today they both tend to play down their role, saying he received no formal coaching. But one thing is certain—already apparent at this young age was Miles’s independence of thought and self-reliance, which was to become even more pronounced later. He seemed to prefer to go his own way, rather than heed the opinions of others.

Miles attended King Edwards School in Edgbaston which set demanding academic standards. His school reports paint a clear picture of the pupil doing just enough work to get by, while concentrating on the more important matter of perfecting his skills at the game he played so well! One tart comment, from General Studies, gives the flavour of the reports:

‘Perhaps one day he will realise there are more things in heaven and earth than chess. At the moment he cannot conceive of such a possibility. Thus his only creditable activity in this subject has been that he has turned up. Otherwise he has said nothing, done nothing, and looked pretty bored. He needs to learn the inestimable value of intellectual humility.’

In 1967, he started playing in the Birmingham Easter Congresses, run by Ritson Morry, the Midland and Hastings chess organizer. He won the West Midlands Under-12 title but, more remarkably, finished runner-up in the Birmingham Open Speed Championships. In his first national competition, aged 12, he scored 50% in the British Under-14 Championship, losing to title winner John Nunn. In the Birmingham Easter Congress 1968, he played no fewer than four games a day, winning the Under-16 and Under-14 titles, the Boys’ Lightning Championship and placing well in the Open Lightning event. Accompanied by his father, he went on to win the British Under-14 title in Bristol, though again losing to Nunn, and then, in 1969, to share 2nd place with Nunn in the British Under-18s, this time gaining his revenge in their individual game.

By the age of 15, Miles was more than a match for national experts. Perhaps his first really significant result in adult competition was when he became the youngest ever Midland Open Champion at the 1970 Birmingham Easter Congress. After this he represented England Under-18s in the Glorney Cup, winning all his games, but, surprisingly, then made a disastrous showing at the Islington Junior. Apparently his accommodation was poor during the tournament and he vowed always to choose better lodgings in the future (indeed, throughout his career, there were shades of Bobby Fischer in his reports of complaints made to hotels around the world.)

Miles surged ahead in 1971, registering his first international success at the Nice Junior Invitation, which he won on tie-break from the World Junior Champion Werner Hug. He then added the British Under-21 trophy to his growing collection. In the 1971/72 Birmingham and District League First Division, he scored a record 9½/10, playing mainly on top board, and on his British Championship debut in 1972, he scored a respectable 50%. He made his first appearance for the full England squad in the Anglo-Dutch match shortly afterwards, winning both his games on board nine.

After famously saving the Fischer Spassky match from collapse, at the Hastings 1972/3 Congress financier Jim Slater announced, ‘I am offering a cash prize of £5,000 to the first British chess player to become a grandmaster.’

This was an enormous sum of money at the time, equivalent to something approaching £100,000 today, and came at just the right moment for Miles’s generation.

Meanwhile, Miles represented England in the 1973 European Junior in Groningen. His second place behind Oleg Romanishin was a tremendous performance since he was two to three years younger than his main rivals. He then crossed the Atlantic to play in the US National Open and Lone Pine events, where his results exceeded expectations. In the latter he lost only in the last round—to American grandmaster Arthur Bisguier.

This was followed by his best result so far when, in Birmingham, he not only became the 4th youngest ever winner of an International Tournament but also obtained his first IM norm. Here he gained his revenge on Bisguier and led by a whole point after 6 rounds. ‘I stayed up half the night analyzing, trying in vain to find a win, when I adjourned against Carleton. I found it frustrating and tiring when I only drew that game.’ Going into the last round, Miles shared the lead, half a point ahead of the British Champion, Eley. ‘I knew how Eley would play, and decided that I would have to checkmate him before he offered me a draw. So I played aggressively to win, and it worked.’

At the World Junior Championship 1973, Miles finished a close second to Russian IM Alexander Belyavsky, despite winning their individual game and despite having his luggage stolen at the start of the tournament!

‘My worst moment in chess was the despair I felt during the 1973 World Junior Championship. About five rounds before the end, I knew I would not win and discovered that it meant more to me than I had realised.’

Tony Miles was a proud man, rarely asking for help from others, but after this personal disappointment he phoned Leonard Barden, seeking his assurance that Bernard Cafferty would be his second at the 1974 event.

By now it was time for him to attend Sheffield University as an undergraduate:

‘When I started to study mathematics I decided that I had to work at my studies at least for the first trimester. I didn’t do anything, but I didn’t play chess during those three months either. I drank a lot and went to discotheques a lot. But afterwards I played at Hastings—and started with 1 out of 7. I simply couldn’t play anymore. It was only in the second half of the tournament that I got going. I made 4½ out of 8, including a win from Kuzmin. So it took me seven rounds to remember how I must play chess.’

At Hastings he also had the better of the play in a hard fought draw against the other Soviet entrant, former World Champion Mikhail Tal. He was fearless against the best players, simply stating that ‘these guys miss things.’

Miles honed his toughness on the 1974 UK weekend circuit, sharing the £1000 Grand Prix with Gerald Bennett—‘Swisses are different, but OK, because they make you aggressive.’ He was a frequent winner of weekenders, due in no small measure to his physical strength and sheer persistence, and was by now, to all intents and purposes, a chess professional. Miles’s chess style was once described as a street-fighter’s:

‘I used that description once, because I learned to play chess mostly at weekend tournaments. Six rounds in one weekend, and you have to win all of those games, so that means you have to fight. Even if there is no way to fight you still have to find a way to win. But just “fighter” is enough, you can drop the “street”.’

Miles’s wish came true and Bernard Cafferty accompanied him to the 1974 World Junior Championship. Manila was rainswept and games were sometimes delayed for an hour while the competitors literally waded through floods to the tournament hall—but he triumphed brilliantly, clinching the title with a round to spare after defeating his main rival Kochiev in a scintillating Sicilian Dragon. Five years later he described this as his favourite game:

‘No small part of my favouritism is due to the fact that it clinched the World Junior Championship for me—one of my best moments in chess.’

In 1975, Sheffield University awarded Miles an Honorary Master of Arts degree in recognition of his achievements in chess, particularly that of becoming World Junior Champion (to this day he remains the only Englishman to have won this coveted title). During 1975, while ostensibly a student, Miles again won the UK Grand Prix, this time outright. He also managed to fit in five international tournaments. Bearing in mind Slater’s £5,000 offer, Miles was pressing hard for a grandmaster result although Raymond Keene was widely expected to become England’s first GM, having already achieved his first grandmaster norm the previous year.

Miles’s breakthrough came at the London International. He easily won the tournament, restricted to under-30-year-olds, beating three of the four grandmasters present and exceeding the GM norm by half a point. The quest for the title had suddenly become a two-horse race between Miles and Keene but in the following Teesside and Hastings tournaments they both fell short of the required norms.

In 1976 Miles received an invitation to a strong tournament in the Russian town of Dubna. Despite the tough opposition and freezing temperature he remained on course for the GM title. But then he lost to Suetin and was left needing a win in the final round, with Black, against the untitled Kostro of Poland. The pressure was on the 20 year old English player, ‘My nerves did a fair amount to counter the strength of my opponent’, and in a tense game he emerged victorious. And so Miles had become England’s first grandmaster and, incidentally, the youngest in the world at that time. With hindsight this provided the springboard for English chess as more players aspired to the title and competed with confidence against the world’s best.

His early record against Soviet players was impressive and right after Dubna he said ‘It’s still about plus six, wins against Belyavsky twice, Bronstein twice, Kuzmin, Vaganian...’ Before he left for Dubna, he had been asked by a friend in London, Eddy Penn, to send a telegram if he was successful in his quest for the title. A fortnight later he received one with the words: ‘A cable—Tony Miles.’

Miles’s success was due in no small part to his superb play in several tough endgames. Respected Soviet trainer, GM Mikhail Shereshevsky, wrote in 1985:

‘The endgame play of grandmaster Miles is characterized by unhurried manoeuvring and the accumulation of small advantages, according to the principle ‘do not hurry’. But when his advantage attains decisive dimensions, the English player is transformed, and he uses all his tactical skill to reach his goal by the shortest path, although quieter, more lengthy roads might be found. A player of the past who acted in this manner was the outstanding Russian Champion Alexander Alekhine.’

Returning to England, he gave interviews at his parents’ house in Birmingham, before departing for the USA:

‘I expect I shall find myself playing chess for a living. I’m far too lazy to do anything else. I really don’t do enough work. It would be helpful if I knew more about the theoretical side of chess. I don’t think I’m very temperamental though I am vaguely moody about my games. Sometimes I feel like playing, sometimes I don’t.’

Miles sensationally tied for first place with Viktor Korchnoi in the 1976 IBM Amsterdam tournament, ahead of nine GMs, thus emphasizing his ability to compete against the world’s best. He represented England on top board at the weakened Haifa Olympiad in 1976, scoring well. He wrote:

‘England’s third place at the Haifa Olympiad has been widely acclaimed as a success. Personally, I am inclined to disagree. The result can be put into perspective by a comparison with the previous Olympiad at Nice. There England finished tenth. However, (because many of the top teams were missing) England effectively moved up from fourth to third. Thus, considering that the England team is supposed to be considerably stronger than ever before, the result can scarcely be regarded as a vast improvement.’

From 1977 to 1979, Miles concentrated on forging a career based on international tournament play and virtually abandoned weekend and open Swiss tournaments. As the world’s youngest grandmaster he earned a good living from top level tournaments—it must be remembered that in those ‘Iron Curtain’ days the USSR would only send two players at most to any Western tournament. At Bad Lauterberg 1977 he lost in his first meeting against the reigning World Champion, Anatoly Karpov. In the Soviet chess journal 64 Karpov wrote:

‘Miles has a well-rehearsed opening repertoire and resourcefulness in critical situations... which makes up for his lack of proper training and technique. He is an extremely nervous man and resembles Henrique Mecking, but once he finds himself in a difficult position, just like the young Brazilian, he forgets about all else and clasps his head in his hands.’

At the next IBM tournament in Amsterdam he repeated his success, winning by a whole point. Miles fared better in his meeting against Karpov in the BBC Master Game final, defending very well to draw the first game, and the replay. The rapid-play final game was a treat for viewers: Karpov had too little time to replace a newly promoted pawn, and at one stage in the furious finish missed a mate in one with his ‘pawn’, before eventually emerging triumphant.

Shortly after this, Miles recorded a sensational second place in the world’s strongest tournament, the Tilburg Interpolis, in 1977. Here he finished second behind Karpov and a point ahead of the rest of the field, sending a clear message that he had World Championship Candidate potential—and all of this within two years of qualifying for his GM title. After losing to Karpov with a dubious opening line, he described the World Champion’s ease of play:

‘Karpov’s so thoroughly prepared, he’s got an opening repertoire that he knows absolutely inside out. It’s almost impossible to gain an advantage from the opening against him. Once he realizes what’s going on in a position he seems to grasp it completely, and he’ll just churn out move after move very quickly. It’s as though everything’s completely worked out in his head and he doesn’t have to work out anything at all, he just walks around and comes back and plays the moves. Fantastic speed of play very frequently, even when he has a tiny advantage, nothing really significant.’

After all the excitement of 1977, the following year must have seemed like something of an anti-climax to Miles. For most of 1978 he was unable to win a single tournament. But he did register two beautiful wins against former World Champion Boris Spassky, employing his patented 4 f4 variation in the Queen’s Indian Defence. These victories showed Miles’s all-round strength—the first was a superb attacking display, the second a technical effort.

Miles married Jana Hartston, an anaesthetist. Jana was Czech woman champion in 1965 and 1967 and regularly won the British Ladies Championship. Unfortunately this marriage broke up after three years. Speaking to the local Evening Mail newspaper Tony said ‘We are more or less on speaking terms—I think this will put me off marriage for a while, though perhaps not for ever. Marriage is illogical anyway.’ Tony and Jana remained good friends.

Miles made his first attempt at the World Championship by competing in the Amsterdam Zonal 1978 and won an Interzonal place by finishing equal first with Timman. It was a good moment to register his only tournament victory that year.

He performed solidly throughout 1979 without winning any tournaments. In the British Championship he lost to a young Nigel Short, who himself almost won the title. The Riga Interzonal started soon after, leaving Miles with little time for preparation. Speelman was his second, though perhaps not an ideal choice since Miles was never at ease with those he viewed as rivals and the two players had a very different approach to the game. Much was expected of him, but, after starting well, his challenge faded as he lost six games to the top eight finishers. British chess fans were disappointed. Miles later said, somewhat enigmatically: ‘It was supposed to be the biggest tournament of my life and I just didn’t feel like playing chess. I wanted to play, but the motivation just wasn’t there.’

Shortly after Riga, Miles finished equal 2nd in the Buenos Aires Clarin event, with Spassky, Andersson, Najdorf and Gheorghiu, behind tournament winner Bent Larsen.

1980 proved to be one of Miles’s most successful years. At the European Team Championship in the remote Swedish township of Skara he faced the World Champion Anatoly Karpov in the first round. In probably the most famous game ever played by an Englishman, Karpov opened 1 e4, whereupon Miles, fresh from a skiing holiday, replied with the unbelievable 1...a6. The audience apparently could not contain their laughter and Miles scored a sensational victory. Karpov appears to have simply not adjusted to the shock of the opening. England’s first grandmaster had achieved another ‘milestone’ in his career by beating a reigning World Champion!

‘When I beat Karpov with 1...a6 and 2...b5 at the European Team Championship in 1980, he did not resign the game personally. The Soviet team captain signed the scoresheet. I heard from others that he felt insulted by my choice of opening.’

Mike Basman had played 1...a6 frequently, calling it the St. George Defence, partly because Miles’s birthday is on St. George’s day! Miles himself suggested the Birmingham Defence, after his home town. His choice of opening was perhaps more than just a whim. At Montreal 1979, Larsen beat Karpov with the Center Counter Defence. Miles wrote: ‘This game adds further weight to the suspicion that the World Champion is a little vulnerable to unusual openings.’ He was the highest scorer on the top board at Skara and England made a breakthrough, capturing the bronze medal.

Phillips and Drew, London 1980, was the strongest tournament to be held in England since Nottingham 1936, which had fielded five World Champions. Showing great determination, Miles shared first place with Korchnoi and Andersson, the first time he had taken top honours in an event of this calibre. His result was hailed by Hartston and Reuben as ‘perhaps the greatest ever by a British player’.

Back to his winning ways, he then tied for first place at Las Palmas with Petrosian and Geller, and also returned to weekenders—‘I always play in weekend tournaments just to keep playing.’ Including weekend tournaments, his winning streak eventually extended to ten straight firsts, including Vrbas where he triumphed ahead of Petrosian and Gligorić. But after losing to Short in the final of the BBC Master Game, Miles congratulated his young opponent, adding: ‘Please try not to make a habit of it!’

His stunning successes in 1980 had perhaps revived his World Championship hopes, but Miles declined his invitation to compete in the somewhat chaotically organized 1982 West European zonal, also stating:

‘If I were ever to become the challenger to Karpov, I should be up against not an individual but a nation.’

It is somewhat curious that Miles only achieved a single victory in the British Championship and that was in 1982. He dominated the event and with further successes at Lloyds Bank and Benedictine, boosted his score to record levels in his third UK Grand Prix win. Then, in 1983, he again sensationally defeated Karpov:

‘One of my best moments in chess, winning a BBC television tournament by beating Karpov. I even had Black in that game!’

In 1984 Miles again won the UK Grand Prix, taking his tally to four. After finishing bottom at Tilburg 1981, for the next two years he did not receive any invitation. But in 1984 he made no mistake and became the first Westerner to win this prestigious tournament which fielded half of the world’s top ten players.

‘Of course, my best result ever was winning the 1984 Tilburg super-GM tournament. ’

After a typically lethargic start, Miles hit top form with five consecutive wins, including victories over Smyslov, Portisch and Timman, thereby surpassing his previous best at Tilburg 1977 where he won four straight games. In several games he showed great tenacity:

‘A bad position does not discourage me, it’s a coincidence that, is an aspect of your profession. Possibly with the exception of Karpov, everybody gets into a bad position once in a while, so that’s not a reason at all to simply lose them. You also have to find a way to save lost positions and try to win them. If possible. It’s the same as my game against Portisch. I don’t remember who, but someone told me that it was a game typical for an Englishman, surviving a terrible position. I think it was a typical I-game.’

Of his recent form, Miles said:

‘Things were wrong with me. I’d put on a stone and it wouldn’t go away. My weight wasn’t going back to normal. I’d lost presence and aggression. My physical condition was suddenly bad. I’d always been physically strong. For the past eight months, I played like an idiot. (Then I won 31 consecutive games on the UK weekend circuit)—such training was like joining Alcoholics Anonymous. But if this is the result, well... I feel positive and much more healthy. I needed a boost. I can’t win the British Championship with the Nigel Shorts and Jonathan Speelmans, but I can win the big one at Tilburg.’ (laughing).

What was Miles’s board presence like? Well, his posture at the board was fairly typical of many players—he held his head in his hands, with his elbows resting on the playing table and he covered his ears. He worked immensely hard at the board.

‘That’s the way it developed over the years and now I can’t do otherwise. It looks very concentrated, but I could just as well go to sleep. Sometimes when I’m tired I close my eyes. Then I lower my hands a little so that nobody notices.’

During play he had characteristic idiosyncrasies. He usually had a glass of milk beside him and used a large silver-strapped watch to cover up his moves on his scoresheet. He often wrote down his proposed reply soon after his opponent had moved but would usually analyse it further before actually executing it, and occasionally changed his mind. He constantly removed invisible specks of dust from the board, pointed his knights to his right, and wore a silver bracelet which he removed at the end of the game. He also tended to blow his nose during play:

‘The handkerchief is a tic. Maybe I’m a bit too sensitive. I wear the bracelet out of superstition. It has some significance to me ... I can’t explain that. ’

At the Thessaloniki Olympiad 1984 England won the silver medal, where John Nunn scored a remarkable 10/11 on board two, thereby jumping ahead of Miles on the Elo rating list.

In the Tunis Interzonal 1985, Miles said that his problems began when he lost on time in a winning position with one move to make against Zapata. He seemed out of sorts, losing to the Interzonal winner Yusupov in only 24 moves. A couple of months later he found his form, sharing first place with Portisch and Ribli, ahead of Smyslov and Gligorić, in the Vidmar Memorial at Portoroz/ Ljubljana.

At Tilburg Interpolis in 1985, Miles’s shared first place was achieved despite crippling back trouble. He played lying flat on his stomach for most of the tournament, on what was dubbed his ‘massage table’! Various players lodged a protest saying that they felt distracted and this made Miles even more determined than usual. Feeling that his integrity was being questioned, he wrote a detailed tournament diary, ‘The Impossible Challenge’, published in New In Chess. Twice he beat Korchnoi, hitherto a difficult opponent for him—his first win being achieved in the conventional sitting position!

At the Lucerne World Team Championship, England finished third and Miles won the silver medal on top board. He now lived in West Germany for much of the time as he not only played in the Bundesliga for Porz/Koln but found it convenient for travelling to European tournaments. During the latter half of 1985 he played the huge number of 86 rated games, regained his spot as the top ranked British player, and rose to equal ninth in the world.

In 1986 Miles contested a match against the new World Champion Kasparov. Although he had chances, he went down fighting ½-5½, commenting wryly ‘I thought I was playing a World Champion, not a monster with 22 eyes who sees everything’. Many commentators believe that this result marked a turning point in his career and the following year he admitted:

‘I don’t consider myself a contender for the World Championship—I don’t consider myself to be quite that good. On a good day I could be about number three in the world. To be better than that you’d have to be completely devoted to chess, which I’m not.’

At the 1986 Dubai Olympiad England came closest yet to capturing the gold medal, finishing half a point below the Soviet team. Then in 1987, after a ten year reign, Miles was overtaken as British number one by Nigel Short, who again qualified for the Candidates.

At the Zagreb Interzonal Miles lost six games, three to tailenders. Around this time the well publicized Miles-Keene dispute broke out. At the Tunis Interzonal in 1985 Keene claimed to have acted as Miles’s second for which he received a payment from the British Chess Federation. However Miles publicly announced that Keene was not his second and felt that the BCF did not investigate the matter fully. The controversy escalated and Miles commenced legal proceedings (which never reached court) and went so far as to indicate that he did not wish to be considered for future English team selection. In fact he transferred his allegiance to the USA. However the dispute took a heavy toll on him, his sleep was badly affected and he suffered a period of ill health which forced him out of chess for a few months.

These were difficult times for Miles—he had never really taken any sort of break from competitive chess before. After some indifferent results, he recovered his form a little and shared first place at the 1988 Dutch Open. In Chess Life, he summed up his unfortunate last place in the 1988 US Championship:

‘I came in with flu and jet lag. They’re not very original excuses, but I never got going. It was much fiercer than I expected. I got carved up in my first three games with Black. Well, that was the end of it. It was only an 11-round tournament, and by the time I started playing it was too late.

The last year has been a disaster for me. I’m just playing and trying to improve again. As you know, I was very ill last year. I spent a period of about three months where I didn’t sleep at all, and my entire nervous system virtually collapsed. All sorts of things went wrong with me. It had nothing to do with my back. Just a serious case of insomnia having enormous side effects.

For a period of six to nine months, I just couldn’t play chess at all. Whenever I tried, I dropped another 25 rating points. Now, I’m okay, but I’ve effectively been out of chess for a year. My openings are a year out of date. I’m rusty. My rating is at the lowest point in the last 13 years since I became a grandmaster. It’s 2500 now; when I was an IM, it was 2510. Down used to be always 2550 and up over 2600.

I don’t want to go on playing chess forever, but I don’t intend to stop because I can’t play. I want to get back up there first. Then if I want to stop, I’ll stop because I want to, not because I can’t play any more. It’s only a game. It’s enjoyable. It’s a nice way to earn a living. As a game itself it’s never had fantastic importance to me.’

Miles did not take up residence in the USA but continued to live mainly in West Germany. Larry Hanken wrote in Chess Life: ‘Miles, a true cosmopolitan, is a British subject who plays for a West German team and lives in West Germany much of the year. He maintains residence in Andorra where he pays his taxes, and unofficially represents the United States of America out of a New York state mailing address [the American Chess Foundation post office box].’

Miles met his second wife Jeannic in Adelaide. They married in April 1989 and moved to Birmingham but the marriage was doomed to failure and they separated in 1991. He seemed to come to terms with the fact that his globetrotting lifestyle would never allow him to be a conventionally ideal husband.

Miles’s form improved in 1989. At Los Angeles he tied for first, ahead of Tal, Larsen and Browne. Then, after a playoff subsequent to the US Championship, he qualified for the Manila Interzonal, where he finished half-way. In the early nineties he spent some time living in Australia, thanks to the hospitality of his friend and travelling companion Alex Wohl.

At the end of 1991 Miles applied for, and was granted, British Chess Federation membership, and indicated that he now wished to play again for England in future events. After a string of wins in Australia, he resettled in Birmingham. Miles was a natural teacher and from this point on he actively encouraged many youngsters in the Midlands, mainly through his Presidency of the Checkmate Chess Club, for which he received no fees.

From now on he competed mainly in Open tournaments. A high point was at Seville 1993 where he made a 2800-result and received a standing ovation for his victory. He described this as ‘the tournament of my life—so far!’

One all-play-all in which he did compete regularly, however, was the Capablanca Memorial in Cuba, where he had an impressive record. In 1994, at Matanzas, he tied for first (Van Wely won on tie-break) and he also scored three outright victories, the most memorable of which was the 1996 event in which 12 of the 14 participants were Grandmasters and he defeated his five nearest rivals! In 1997 he finished second behind his friend, Peter Leko.

In 1995, he won a strong all-play-all in Benasque ahead of Andersson and Psakhis, while at the PCA Intel Rapid Chess Grand Prix in London he scored a famous victory over Vladimir Kramnik in the quarter-final after a playoff in front of a partisan audience. At the end, he punched the air in delight.

Miles first played for Slough in the Four Nations Chess League (4NCL) when they won their first national title in 1995/6. He became team captain a couple of seasons later and successfully guided the team to two further titles. In the 1997 British Championship he tied for first (Adams and Sadler won the tie-break) and in 1998 came 3rd, with wins in the last two rounds against Speelman and Short.

In 1999 he was diagnosed with diabetes. His energy levels were affected and he reduced his playing schedule. At his final tournament, the British Championship 2001, he withdrew prior to the final round due to illness. But he continued to captain and play for Slough in the 4NCL where he was laying a strong junior foundation for the club. In Birmingham he competed daily on the local bridge circuit, a game which he threw himself into with the same passion as he showed for chess.

In November 2001, Tony Miles died suddenly from heart failure related to diabetes. He passed away at home after having spent much of the previous day with friends. A one minute silence was held in his memory at the start of the seventh round in the European Team Championships in Leon...

Summary

Tony Miles’s chess career spanned over 30 years, commencing just as Informator was launched and long before the start of the computer generation. A strong junior, his rise was rapid from the age of 18. He won the World Junior Championship in 1974, gaining the International Master title. Then within two years he became a Grandmaster, England’s first and the youngest in the world at the time. After impressive results in 1976 and 1977, Miles had aspirations for the World Championship. However, his results against the World Champion Karpov and top players such as Korchnoi, Portisch and Timman were perhaps not encouraging—these players were theoretically well prepared. In 1984, he commented on his approach to study:

‘(at University) The mathematical studies flopped—quickly, because it couldn’t fascinate me. I could find no impetus whatsoever to study for an examination that I would have to do in three years time. The same as chess, I can’t study something abstract that does not have any practical significance for me at the moment. There must be a challenge, an opponent and some excitement.’

After the Riga Interzonal 1979, it seems that he more or less abandoned hopes of challenging for the world title:

‘I want to be among the top ten in the world. But how much do I want to improve? The World Championship is out of the question. I don’t have any concrete ambitions. I want to get to the Candidates and that’s about it.’ (1980)

Throughout his career Miles played frequently—he revelled in the fight. He won tournaments at the highest level—Tilburg Interpolis 1984 and 1985 are perhaps his best results. An original thinker, Miles was a sharp tactician and a chess artist with a high level of endgame technique. He played many beautiful games. He beat the reigning World Champion Karpov twice, scored wins against former title holders Spassky, Tal and Smyslov, and frequently defeated World Championship Candidates. He is one of the strongest players not to have reached the Candidates stage of the World Championship.

Miles represented England on top board from 1976 to 1986, was the top scorer at the European Team Championships in 1980 and won the silver medal at the World Team Championships in 1985. During this period the English national team enjoyed unprecedented success, winning bronze medals at the 1976 Haifa Olympiad and European Team Championships in 1980, and silver medals at the Thessaloniki 1984 and Dubai 1986 Olympiads.

Miles’s impact on the English game was immense and he ranks among the greatest ever English players. He was well liked and made friends the world over. He always amazed lesser players and amateurs by his willingness to talk chess matters to them, valuing their opinions. He is sadly missed.

Against Anatoly Vaisser, at the Elista Olympiad in 1998, Miles played a game so bizarre that it appeared as if his sense of humour had taken over completely:

‘That’s my nature. I am not very serious when I play, I mean I do concentrate but that is only a part of it—I have a strong tendency to look at crazy things first. When promoting a pawn I prefer a bishop to a queen if that is possible. I am very fond of, let us say, three rooks on the board. In a weekend tournament I had that once, and instead of resigning my opponent allowed himself to be mated beautifully in the middle of the board. That appeals to me.’

Tony Miles, England’s First Grandmaster, 1955-2001.

2: “I played every night for a year until I got bored”

In this early game, 12 year-old Miles opens 1 e4 and faces the Sicilian Dragon, an opening which he later enthusiastically adopted himself:

1

A.J.MilesWhite

P.K.BissicksBlack

Sunday Times Schools Competition 1967

Sicilian Defence

(notes by 12 year old Tony Miles)

1 e4 c5 2f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4xd4 f6 5c3 g6 6e3g7 7e2c6 8 f3 0-0 9d2 d5 10xc6 bxc6 11 0-0-0

Pinning the d-pawn.

11..e6 12 e5

Here come the pawns.

12...d7 13 f4a5 14 g4fd8

So as to play ...d4 and xa2. This was impossible before: 14...d4 15 xd4 xa2 16 xd7.

15 a3ab8

Seemingly threatening ...xb2, xb2 b8+, but b5! wins.

16b1

Relieving any danger.

16...xd2+ 17xd2b6

To cover the a-pawn.

18f1

Threatening to advance the pawns.

18...f8?

Useless.

19 f5

Charge.

19...gxf5 20 gxf5c8 21 f6

On they come.

21...exf6 22 exf6h8 23c5+e8

23...g8 24 g1+.

24e7

Tearing open Black’s position.

24...h3

If 24...d7 25 g1 wins.

25g1d7?

25...dc8 26 a6 wins.

26g8 mate.

* * * *

In the next junior encounter Miles gains his revenge against John Nunn, having previously lost twice to him in the British Under-14 Championships. The game followed theory, known to Miles, and he only used five minutes on his clock:

2

A.J.MilesWhite

J.D.M.NunnBlack

British U-18 Championship 1969

Max Lange Attack

1 e4 e5 2f3c6 3c4f6 4 d4 exd4 5 0-0c5 6 e5 d5 7 exf6 dxc4 8e1+e6 9g5d5 10c3f5 11ce4b6 12 fxg7g8 13 g4g6 14xe6 fxe6 15g5 h6 16f3 hxg5 17f6+f7

18 xe6! xe6 19 e1 + e5 20 d5+ Black resigned.

* * * *

By the age of 15 Miles was more than a match for strong national players. He made his first real breakthrough when he won the Nice Junior Invitation in 1971:

3

A.J.MilesWhite

P.SzekelyBlack

Junior International, Nice 1971

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4xd4f6 5c3 a6 6 f4

Rather than getting lost in a main line I decided on a slower variation.

6...c7 7d3 e6 8 0-0bd7 9 a4 b6 10f3b7 11 g4

It’s useful to move Black’s king knight to prevent a later ...d5.

11...c5 12 g5fd7 13d2

On 13 f5 0-0-0 seems playable, after which White’s king might become exposed.

13...g6 14 b4

An interesting idea, forcing the exchange leaving White with a space advantage and the open c-file for the two bishops.

14...7 15ce2xd3 16 cxd3 0-0 17acld8 18c6e8 19f2c8 20cd4b8

Trying to exploit White’s exposed queenside pawns and tempt b5 allowing the knight to come back to c5.

21xc8xc8

If 21...xc8 22 f5 looks strong.

22f3

Now if 22...xa4 23 xb6 c6 24 c1 d7 25 c7 picks up a pawn (25...d8 26 xc6).

22...d8 23e3d7 24c1 a5

This brings the game to life—if White allows Black to establish a knight on c5 life gets difficult—so I felt obliged to induce complications. (If 25 bxa5 bxa5 26 c6 c5! breaks out: 27 xc5 dxc5 28 xc5 xd3).

25ed4 axb4 26c6e8 27xb6 b3

On 27...c5 28 xb4 xa4 29 d4 keeps some chances, but ...b3 looks the best active chance as the b-pawn is extremely useful.

28d4 e5

At the time Black played this I (with just over 10 minutes left to reach the time control at move 40) was furiously trying to calculate the consequences of 28...c5 and if 29 xc5 xc6 or 29 xg7 xd3. Some days and much analysis later I eventually found: 29 xg7 xd3 (not xg7? d4+) 30 b6! xc1 (again if xg7 d4+) 31 f6! with a winning attack: 31...h5 32 gxh6 (threat g5) 32...h7 33 g5+ xh6 34 f2 and wins.

29 fxe5 dxe5 30b2a6

On 30...e6 31 a3 e8 32 e7+ and Black’s queen’s bishop is loose.

31a3xd3 32e7+

Stronger than 32 xf8 xf8 when Black’s pieces come to life and White’s pawns are decidedly groggy.

32...h8 33c8xc8 34xc8xc8 35d2

The point—Black’s bishop and knight are skewered.

35...xe4

Black can save the piece by 35...b2, but after 36 xb2 c5 37 xe5, the holes around his king begin to show up and his pieces are awkwardly placed.

36xd7f5 37b7 e4 38e1d4+ 39g2 Black resigned.

4

A.J.MilesWhite

A.DakeBlack

Lone Pine 1973

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2f3c6 3 d4 cxd4 4xd4b6 5b3f6 6c3 e6 7d3 a6 8 0-0e7 9e3c7 10 f4 d6

Thus a common line is reached but with White a move ahead thanks to 4...b6.

11f3d7

A little passive, but being a tempo behind the normal line, it may be necessary.

12h1b4 13 a3xd3 14 cxd3c6 15ad 0-0 16d4ac8

Perhaps 16...d7 is more accurate.

17 f5 e5

Now if 17...d7 18 fxe6 fxe6 19 h3 wins a pawn: 19...e5?? 20 xc6 bxc6 (20...xc6 21 d5) 21 xf6! winning a piece.

18xc6 bxc6 19d5xd5?

This leaves Black with a totally static position. 19...b7 was much better, although White’s position is still preferable.

20 exd5 c5

Now Black’s bishop is terrible and he has no counterplay as White quietly masses on the kingside.

21c4fe8 22h5f6 23g4d8 24h6

The start of a quite pretty, and completely forced, winning line.

24...h8

If 24...f8 25 xg7 xg7 26 f6 winning. Or 24...g6 25 fxg6 fxg6 26 xg6+ hxg6 27 xg6+ h8 28 xf6 c7 29 xd6 winning easily.

25xg7+!xg7

26 f6!xf6?

I really was very disappointed at this move. I had been eagerly waiting for 26...xf6 (if ...f8 27 g5 or 27 xf7) 27 h4! g8 (27... xh4 28 xf7 forcing mate on h7) 28 xh7+ f8 29 h6! g7 30 g6! winning.

27xf6xf6 28h6 Black resigned.

5

A.J.MilesWhite

A.BisguierBlack

Birmingham International 1973

Ruy Lopez

1 e4 e5 2f3c6 3b5f6 4 0-0xe4 5 d4d6 6xc6 dxc6 7 dxe5f5 8xd8+xd8 9c3e8 10e2e6 11f4d5 12xd5 cxd5 13e1

Up to here all ‘book’. Now 13 g4 maintains an edge for White. The text is an effort to get out of the book line, but it’s less accurate than 13 g4.

13...c5 14f4 c6 15ad1 h6 16 h3

Dubious. 16 g4, as suggested by Bisguier, is probably best. Now Black takes the initiative.

16...g5 17c1e7 18h2

White now has some difficulties. Possible improvements might be 18 g4 g7 19 e3 or 18 d2 preparing c4, but Black retains an edge in any case.

18...ag8 19g4 h5 20e3

I must admit to being most unconvinced by this manoeuvre but I couldn’t find much else.

20...h4

Now White is about to get squashed by 21...g4, and if he exchanges on g4 then ...f3+ is a murderous threat. Clearly he must strike back in the centre immediately, since, for a moment at least, Black’s massed forces are rather compromised, viz his queen’s rook and knight cannot be regrouped without leaving the g-pawn hanging and the king’s rook must wait for the queen’s rook to move. My original intention had been 21 c4 but unfortunately Black can ignore this and play 21...g4! and break through first. So there is only really one other way to hit back, and therefore it must be played. So....

21xd5+!

This certainly shouldn’t win with best play—indeed, it may well lose—but over the board it must be the best chance.

21...cxd5 22xd5 b6

Black seemed to be rather taken aback by the sacrifice, and began to consume fairly large amounts of time without really finding the best moves. Here I expected 22...b4 23 e4 e6 24 b5 e7 25 xb7 with the possibility of a4-a6+ with an obscure position. Also, not to be taken lightly is the immediate 22...g4 e.g. 23 xc5 gxh3 24 e3 xg2+ 25 h1 hg8 with winning threats, but 24 c3 seems to hold. If Black wishes to continue as in the game then 22....b6 would avoid a few of the ensuing tactical tricks.

23 e6

Obviously the only continuation. If now 23...fxe6 24 xg5+ xg5 (other moves lose the knight) 25 xg5 with an interesting ending which White shouldn’t lose.

23...f5?

Since it’s not clear how Black can save himself after this, the obvious alternative 23...f6 must be examined. After 24 d7+ e8 White still has the possibility of 25 b4, but Black has better chances than with the pawn on f5.

24d7+

24...f6?

At the time Black’s loss was attributed directly to this move. After 24...e8 my first insane-looking suggestion was 25 b4 intending -b2-f6. A brief post-mortem produced the following hairy lines:

(a) 25...xb4 26 ed1 g4 27 b2 gxh3 28 f6 f3+ 29 f1 hxg2+ 30 e2 g1=+ 31 xg1 xg1+ 32 f1 e7 33 xe7+ d8 34 xa7+ c8 35 xh8 with advantage to White.

(b) but 25...g4 26 b2 gxh3 27 xh8 f3+ 28 f1 hxg2+ 29 e2 d4+! winning.

A slightly more extensive analysis produced some improvements: In (b) 26 bxc5 gxh3 27 c6! threatening c7 wins e.g.

(i) 27...xg2+ 28 f1 h2 29 e2 g1 30 c7 xe1+ 31 d3 d1+ 32 d2 winning.

(ii) 27...f3+ 28